Abstract

Direct Lumbar Interbody Fusion (DLIF) and eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF) are the most common surgical platforms available for performing transpsoas spinal fusion but no study has been carried out to compare them. We evaluated 21 DLIF and 22 XLIF cage positions by measuring the distance between the posterior vertebral border and the centre of the cage normalised to the midsagittal length of the inferior end plate. We found that DLIF cages were significantly more anteriorly located than XLIF (0.65 vs 0.52, p = 0.001) at L4-5, suggesting that XLIF would permit implantation of wider cages than DLIF.

Keywords: Lateral transpsoas, Lumbar vertebrae, Spinal fusion, Cage position

1. Introduction

The lateral transpsoas approach is a novel minimally invasive technique for accessing the anterior vertebral column of the lumbar spine. Characterised by a unique lateral line of attack, it allows placement of cages spanning the entire width of the vertebrae without disrupting the normal stabilising ligaments of the spine. This affords a unique capability for enabling the interbody cages to engage the dense cortical bone at the apophyseal rings, thus reducing the risks of graft subsidence and maintaining indirect decompression unparalleled by any traditional anterior or posterior approaches.

Nevertheless, one major caveat in exploiting the advantages of this approach is the proximity of the lumbar plexus. As the nerves of the plexus descend within the psoas muscle, they migrate progressively anteriorly towards the centre of the intervertebral disc.1, 2, 3 As a result, the available operating window becomes increasingly narrow and shifted towards the anterior quadrants of the disc space as one approaches the lower lumbar segments. This in turn restricts the anteroposterior (AP) width of the cages implantable and potentially precludes a safe working zone particularly at L4-5.

To overcome this obstacle, specially designed surgical platforms incorporating tailor-made retractor and neuromonitoring system have been introduced in recent years to maximise access and promote safety. Conceivably systems that would allow positioning the working channel as close to the lumbar plexus as possible without risking neural injury would be most desirable in maximising the AP width of the operating window and the choice of larger cages. Currently there are two main surgical platforms known as eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF, NuVasive Inc., San Diego, CA)4 and Direct Lateral Interbody Fusion (DLIF, Medtronic, Memphis, TN)5 for achieving this. While both systems similarly embrace the core techniques of triggered electromyographic (EMG) monitoring and the use of expandable tubular retractors to establish minimally invasive access through the psoas muscle, they differ significantly in their initial approach to the disc space and the establishment of the operating window.

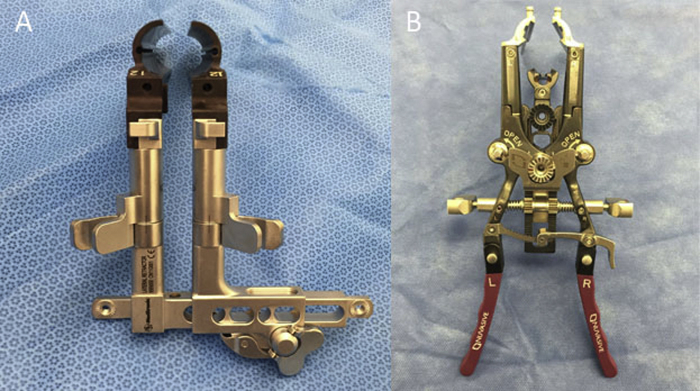

In DLIF, the design is based on a pair of traditional two-blade expandable tubular retractors—the retractors were split into left and right halves allowing craniocaudal expansion (Fig. 1). The initial transpsoas approach targets at anchoring the muscle dilators to the centre of the disc space as guided by lateral fluoroscopy and evoked EMG monitoring. The retractor system (22 mm diameter) was then placed over the dilators and secured in place with a table-mounted arm assembly. In XLIF, the design is based on a three-blade system—the tubular retractors are split into left, right and centre blades. The initial approach aims to anchor the muscle dilators posterior to the centre of the disc space. The retractor system (12 mm diameter) was then inserted and fixed in position by anchoring the centre blade to the vertebral interspace with an intradiscal shim and also to a table mounted arm assembly. The surgical field can then be expanded by retracting the muscle with the right and left blades craniocaudally and anteroposteriorly.

Fig. 1.

(A) A DLIF retractors are composed of a pair of left and right retractor blades. The operative field is fashioned by expanding the retractor blades craniocaudally. (B) An XLIF retractors consist of a centre blade that acts as a posterior fixation point. It can be anchored to the disc space with a shim. The surgical field is established by expanding the left and right blades craniocaudally and anteriorly.

Whilst these two systems are similarly based on the principles of tubular surgery, the difference in the design of the retractors implies an important distinction in their strategies for establishing the initial transpsoas entry. In DLIF, because of the concentric design, the centre of the operative window coincides with the initial docking position of the muscle dilators. Thus when searching for an initial safe passage through the psoas, good clearance of the lumbar plexus is mandatory as subsequent advancement of muscle dilators and retractors may unduly displace and stretch the lumbar plexus located posteriorly. In contrast, for XLIF, the initial entry is designed to be a posterior fixation point. The operative window is established by winding the left and right retractor blades anteriorly and craniocaudally. The final expanse of the operative window is anterior to the initial entry point.

Thus, collectively, when applying the DLIF retractors there may exist a tendency to place the initial dilator more anteriorly to safely avoid the lumbar plexus than when applying the XLIF retractors as the initial dilator marks the posterior fixation point in the latter and the lumbar plexus will be protected behind it. Currently no study has been performed to compare which system would favour wider operative window and cages. We therefore performed a radiographic study to evaluate quantitatively cage positioning in a cohort of patients who had undergone either a DLIF or XLIF procedure and conducted a multiple regression analysis to determine whether a difference exists between these two systems.

2. Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review to identify patients who had undergone either a DLIF or XLIF procedure from October 2012 to January 2015. During this period these two systems were used non-selectively by a single surgeon (TS) at our institution. The indications for surgery included spondylolisthesis, degenerative scoliosis, degenerative disc disease, canal and lateral recess stenosis, and adjacent segment disease. Patient parameters including treatment level, the presence of spondylolisthesis and postoperative neurological deficits were included in the analysis. The study was approved by local institutional human research ethics committee.

2.1. Surgical techniques

The techniques used in this study followed those described by Ozgur et al. and the details can be found in their publication.4 The same surgical protocol was applied for either system and all procedures were supplemented by pedicle screw instrumentation secured under cantilever compression. In addition, several technical points pertinent to this study are as follows. First, we used the midpoint of the disc space as our standard target for docking the muscle dilators when establishing the initial transpsoas corridor. This was applied for either system. Second we accepted current thresholds of greater than 10 mA as safe during the initial entry but if it fell below this limit the trajectory would be revised and a more anterior target would be trialled until safe current thresholds were reached. As neural monitoring is available for each dilator insertion in XLIF but not in DLIF, the current thresholds generally would drop progressively (sometimes down to less than 5 mA) as larger dilators were inserted during XLIF cases. However, we adopted a strategy that no revision of the dilator position would be made as long as the first dilator was above the safe threshold (10 mA). Third, to enhance safety and accuracy, a true lateral trajectory was strictly adhered to during cage implantation. To this end, anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopy was used repeatedly to ensure the coronal axis of the vertebrae was orthogonal to the horizontal plane.

2.2. Imaging analysis

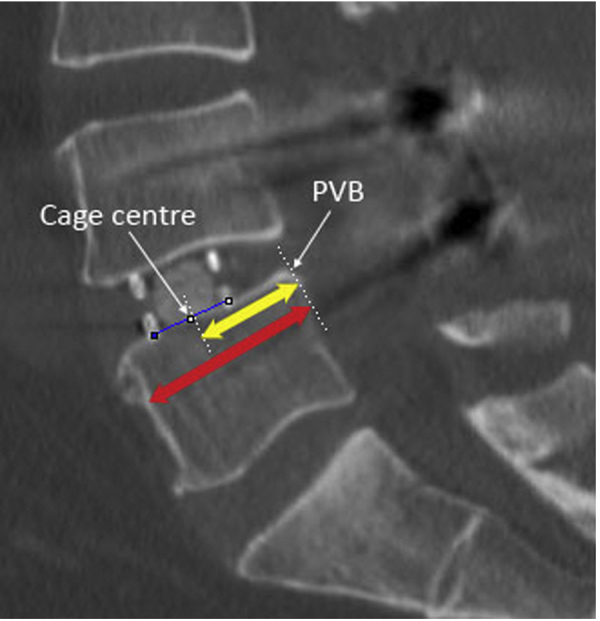

The primary outcome measure is cage positioning in the midsagittal plane along the inferior end plate as determined by postoperative CT scans (Fig. 2). The position was quantified by the distance between the posterior vertebral border (PVB) and the centre of the cage, normalised to AP width of the inferior end plate (IEP). The centre of the cage was defined as the midpoint between the anterior and posterior radiomarkers of the cage. A Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine viewer (Inteleviewer, Intelerad, Westminster, CO) was used for all imaging analysis. Measurements were performed independently by two authors (TS and EN) on two occasions and intraobserver and interobserver reliability was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient.

Fig. 2.

A midsagittal CT scan showing a DLIF cage implanted into the L4-5 disc space. The cage centre is located by the midpoint between the anterior and posterior radiomarkers of the cage (blue line). The yellow arrow indicates distance between the posterior vertebral border (PVB) and the centre of the cage. The red arrow indicates the anteroposterior width of the inferior end plate.

2.3. Statistical and power analysis

We determined that in order to have 80% power to detect a 10% difference in cage position with a type I error of 5% and a standard deviation of 0.125 (assuming cage centre falls within 0.25–0.75, that is the middle anterior and middle posterior quarters, 95% of the time), a sample size of 13 levels or more was required. Univariate analysis with two-tailed t-test and Fisher's exact test were applied for continuous variables and categorical variable respectively. A multiple regression was conducted for multivariate analysis. SPSS 22 was used for all statistical calculation.

3. Results

We identified 57 lumbar segments in 43 patients who had a lateral transpsoas interbody fusion performed through either DLIF or XLIF. The baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Univariate analysis revealed no difference between DLIF and XLIF regarding patient demographics (sex and age), the spinal level treated, and the presence of spondylolisthesis. However, for DLIF, the normalised mean cage position at the L4-5 level was found to be 0.65 (0.60–0.69, 95% CI) compared with a mean of 0.53 (0.49–0.57) for other DLIF levels, while for XLIF the overall normalised mean cage position was recorded to be 0.52 (0.48–0.55, 95% CI) with no difference noted in cage positions between the L4-5 level and the remainder. The difference noted at L4-5 for DLIF compared with other DLIF levels is statistically significant (p = 0.0002) translating to an absolute average difference of 3.3 mm (1.0–5.6, 95% CI).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| DLIF | XLIF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female | 8:13 | 9:13 | 1.00 |

| Mean age (y) | 60.2 | 68.6 | 0.05 |

| Segments | 0.09 | ||

| L1/2 | – | 2 | |

| L2/3 | 3 | 3 | |

| L3/4 | 12 | 6 | |

| L4/5 | 14 | 17 | |

| Spondylolisthesis | 7 | 11 | 0.36 |

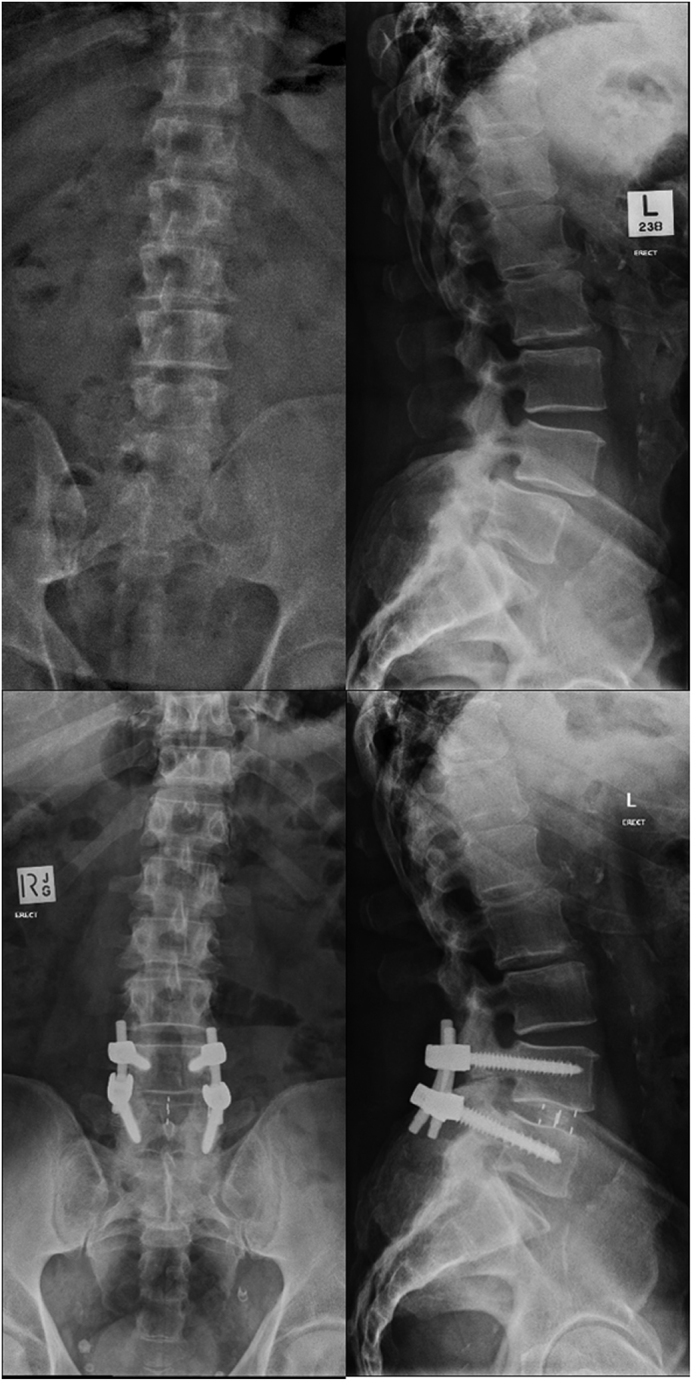

There is a significant difference correspondingly in the average cage position at L4-5 between the DLIF and XLIF groups, with DLIF cages averaging 4.4 mm (2.1–6.7, 95% CI) more anterior to XLIF cages despite a lack of overall difference (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Table 2 summarises the findings. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict normalised cage position from surgical type, spondylolisthesis and treatment level at L4-5. While the presence of spondylolisthesis did not predict cage position, both surgical type (p = 0.001) and treatment level (p = 0.019) statistically significantly did.

Fig. 3.

AP (left) and lateral (right) erect radiographs of a patient who had a DLIF procedure performed at L4-5. The preoperative imaging (top) shows a grade I spondylolisthesis and the postoperative imaging (bottom) shows complete reduction of the subluxation. The normalised cage position is 0.60.

Fig. 4.

AP (left) and lateral (right) erect radiographs of a patient who had an XLIF procedure performed at L4-5. The preoperative imaging (top) shows a grade I spondylolisthesis and the postoperative imaging (bottom) shows complete reduction of the subluxation. The normalised cage position is 0.52.

Table 2.

The anteroposterior cage centre position along the midsagittal plane. Values in parentheses denote standard deviations.

| Mean absolute difference (mm) | Normalised mean cage centre position |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLIF | XLIF | p | ||

| All | 2.7 | 0.56 (0.13) | 0.52 (0.09) | 0.13 |

| L4/5 | 4.4 | 0.65 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.10) | 0.0001 |

The rate of postoperative motor and sensory deficits by six weeks and ODI score improvement did not differ between the two groups (Table 3). Intraclass correlation coefficient for measurement of cage positions showed good intra- and interobserver reliability (0.88 and 0.91 respectively).

Table 3.

Summary of clinical outcome.

| DLIF | XLIF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postop sensory disturbance at 6 weeks | 1 | 2 | |

| Postop motor deficits at 6 weeks | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean improvement in Oswestry Disability Index | 14 | 21 | 0.31 |

| Mean follow up duration (months) | 11.2 | 9.8 | 0.47 |

4. Discussion

The development of lateral transpsoas approach has been advanced by specially designed surgical platforms with tailored neuromonitoring console, muscle splitting retractor system, and long tapered instruments to allow a minimally invasive access to the anterior column of the lumbar spine. Our study has demonstrated for the first time that the choice of surgical platforms can influence radiographic outcome when performing lateral transpsoas interbody fusion to the L4-5 segment. Previous cadaver studies have shown that the lumbar plexus at L4-5 could reach as far anterior to the midpoint of the disc space and limit access to the posterior half of the vertebral column.1, 2, 3 Thus to optimise the operative window at L4-5, a strategy to get as close as possible to the lumbar plexus posteriorly, yet without undue displacement of the nerves during retractor dilation, would be ideal. The design of XLIF with a posterior fixation point, therefore, may confer significant advantages over DLIF in protecting the nerves yet maximising their proximity at the same time. Our results corroborate this hypothesis—while a significant anterior shift of cage positions into the middle anterior quadrant occurred with DLIF at L4-5, a midpoint location was maintained when using the XLIF system. Correspondingly the difference disappeared in other levels cephalad, where the lumbar plexus is located in the posterior quadrant of the vertebral column and thus nerve proximity would impose fewer limitations on surgical access.1, 2, 3

The benefits of a larger operative window and consequently the use a wider cage in lateral lumbar interbody fusion have been highlighted by various studies. In a cadaver study, Pimenta et al. compared a 26 mm wide cage with a standard 18 mm cage. They found that the 26 mm cage conferred significantly less range of motion and thus greater stability than the 18 mm cage when multidirectional non-destructive flexibility testing was performed.6 Clinically the benefits were demonstrated correspondingly by Marchi et al. in a retrospective study of 74 patients who had stand-alone lateral interbody fusion performed with either a standard 18 mm cage or a wide 22 mm cage.7 They found that the use of a 22 mm cage was associated with lesser subsidence than an 18 mm cage and the effect was translated radiographically to better improvement in disc height and segmental lordosis. Such benefits are again reflected in another retrospective study of 140 at-risk osteoporotic patients, in which the authors found a 14% subsidence rate when the standard 18 mm cages were used comparing to a markedly lowered 2% rate when the 22 mm wide cage was employed.8

In light of these, it should be noted that our findings of cage positioning shift to the middle anterior quadrant by an average of 4 mm from the midpoint with DLIF when compared with XLIF at L4-5 is clinically significant as this could exert significant limitation in the choice of a wider 22 mm cage. Considering the superior AP vertebral body width is about 35 mm on average at L5,9, 10 a normalised cage position of 0.65 means that there would be only 12 mm gap between the centre of the cage and the most anterior point of the vertebral body. Placing a 22 mm wide cage would therefore risk rupturing the anterior longitudinal ligament and implant dislodgement.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively analyse cage position in lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Previous studies have evaluated AP cage position in relation to improvement in foraminal aperture and segmental lordosis but no quantitative analysis about cage position has been performed.11, 12 Nevertheless it has been estimated that in about two-thirds of the cases, the cage centres would lie within the middle 20% of the vertebral body according to the available semi-quantitative data in the literature.11, 12 Our findings are in good agreement with this published data in that our average normalised cage centre position is close to 0.5 and the standard deviation is about 0.1, thus yielding an estimate that about 68% of our cages would be located in the middle 20% of the vertebral body. In practical terms, these results suggest that based on the abovementioned average dimension of the lumbar vertebrae, placement of a wide 22 mm cage would be feasible in most cases.

Several caveats should be noted when interpreting the results of our study. First, apart from the difference in the design of surgical platforms, surgeon-controlled factors such as variations in surgical techniques and preference would inevitably play a significant role in radiographic outcomes. In this regard it should be noted that our single surgeon series has provided some control in treatment heterogeneity and minimise the confounding effects of these variables. For instance, our surgical protocol employs a uniform neuromonitoring strategy to establish a working zone at the centre of the disc space and emphasises the liberal use of fluoroscopy during cage implantation to ensure a true lateral trajectory. Such measures, applied by a single surgeon, help provide technical uniformity and reduce surgeon related factors in influencing cage positioning. Second, anatomical variations in the location of the lumbar plexus and the presence of spondylolisthesis can conceivably limit the operative window notwithstanding which system is used. While some cadaver studies specifically examining lumbar plexus anatomy within the psoas muscle have indicated that anatomical variations in this region are not typical,2, 3 some authors have recently reported that in some cases variations in the location of the psoas relative to the vertebral bodies alone may significantly influence the availability of a safe working zone.13 In our study we have attempted to control this by performing multiple regression analysis for spondylolisthesis and our negative result supports the notion that variations in individual regional anatomy tends not to be a dominant factor. This corroborates with the findings in the literature that lateral lumbar interbody fusion is generally safe and feasible for patients with spondylolisthesis, even for those with a grade II spondylolisthesis at L4-5.14, 15, 16 Third, it is important to note that the primary outcome measure of our study is the quantitative AP cage positions as measured from the postoperative CT scans and our study is powered to specifically address this question only. Whether the findings can be translated to improved clinical outcome or fusion rate remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, our study has shown a significant difference in AP cage positioning between a cohort of DLIF and XLIF patients—at L4-5, cages tended to be placed further anterior in the anterior middle quadrant in DLIF patients when compared with XLIF, with which a midpoint position tended to be maintained. Such difference disappeared in other levels cephalad. The results suggest that the design of a retractor system could significantly influence cage placement in lateral transpsoas interbody fusion at L4-5 and such consideration should be taken into account when selecting the appropriate surgical platform, particularly when maximisation of implant footprint is desired.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Davis T.T., Bae H.W., Mok J.M., Rasouli A., Delamarter R.B. Lumbar plexus anatomy within the psoas muscle: implications for the transpsoas lateral approach to the L4–L5 disc. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2011;93(16):1482–1487. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerin P., Obeid I., Bourghli A. The lumbosacral plexus: anatomic considerations for minimally invasive retroperitoneal transpsoas approach. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012;34(2):151–157. doi: 10.1007/s00276-011-0881-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uribe J.S., Arredondo N., Dakwar E., Vale F.L. Defining the safe working zones using the minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach: an anatomical study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(2):260–266. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.SPINE09766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozgur B.M., Aryan H.E., Pimenta L., Taylor W.R. Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2006;6(4):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight R.Q., Schwaegler P., Hanscom D., Roh J. Direct lateral lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative conditions: early complication profile. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(1):34–37. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181679b8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimenta L., Turner A.W., Dooley Z.A., Parikh R.D., Peterson M.D. Biomechanics of lateral interbody spacers: going wider for going stiffer. Sci World J. 2012;2012:381814. doi: 10.1100/2012/381814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchi L., Abdala N., Oliveira L., Amaral R., Coutinho E., Pimenta L. Radiographic and clinical evaluation of cage subsidence after stand-alone lateral interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(1):110–118. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le T.V., Baaj A.A., Dakwar E. Subsidence of polyetheretherketone intervertebral cages in minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(14):1268–1273. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182458b2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masharawi Y., Salame K., Mirovsky Y. Vertebral body shape variation in the thoracic and lumbar spine: characterization of its asymmetry and wedging. Clin Anat. 2008;21(1):46–54. doi: 10.1002/ca.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou S.H., McCarthy I.D., McGregor A.H., Coombs R.R., Hughes S.P. Geometrical dimensions of the lower lumbar vertebrae – analysis of data from digitised CT images. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(3):242–248. doi: 10.1007/s005860000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepler C.K., Huang R.C., Sharma A.K. Factors influencing segmental lumbar lordosis after lateral transpsoas interbody fusion. Orthop Surg. 2012;4(2):71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-7861.2012.00175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepler C.K., Sharma A.K., Huang R.C. Indirect foraminal decompression after lateral transpsoas interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(4):329–333. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.SPINE11528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voyadzis J.M., Felbaum D., Rhee J. The rising psoas sign: an analysis of preoperative imaging characteristics of aborted minimally invasive lateral interbody fusions at L4-5. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(5):531–537. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.SPINE13153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadian A., Verma S., Mundis G.M., Jr., Oskouian R.J., Jr., Smith D.A., Uribe J.S. Minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas interbody fusion for L4-5 spondylolisthesis: clinical outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(3):314–320. doi: 10.3171/2013.6.SPINE1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khajavi K., Shen A., Hutchison A. Substantial clinical benefit of minimally invasive lateral interbody fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:314–321. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3841-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchi L., Abdala N., Oliveira L., Amaral R., Coutinho E., Pimenta L. Stand-alone lateral interbody fusion for the treatment of low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis. Sci World J. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1100/2012/456346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]