Mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene are the most common cause of familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) [20, 32]. Common polymorphisms in LRRK2 have been shown to modulate the risk for sporadic PD [6, 23, 24] strengthening the idea that inherited and sporadic PD share common underlying pathways. Although LRRK2 has been associated with a variety of cellular functions, including autophagy [1], mitochondrial function/dynamics [30] and microtubule/cytoskeletal dynamics [12], the overall physiological function of LRRK2 and its role in PD are only partially understood. Relatively recent studies also support a role for LRRK2 as regulator of inflammation. Substantial levels of LRRK2 protein and mRNA have been reported in immune cells like peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), including B-cells, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells [9, 13, 16, 29]. Moreover, LRRK2 has been shown to be involved in the activation and maturation of immune cells [29], in controlling the radical burst against pathogens in macrophages [9] and in modulating neuroinflammation by cytokine signaling [10, 19]. Remarkably, elevated levels of serum cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNFα) in PD patients [4, 22, 27] point to an involvement of the peripheral immune system in the pathogenesis of PD. Recently, we found an enrichment of “classical” CD14++CD16− monocyte subpopulation in the peripheral blood of PD patients together with a dysregulation of inflammatory pathways, phagocytosis deficits as well as hyperactivation of PD monocytes in response to LPS treatment, which correlated to PD severity [11]. Here, we sought to study the contribution of LRRK2 to the dysregulation of monocytes in Parkinson’s disease.

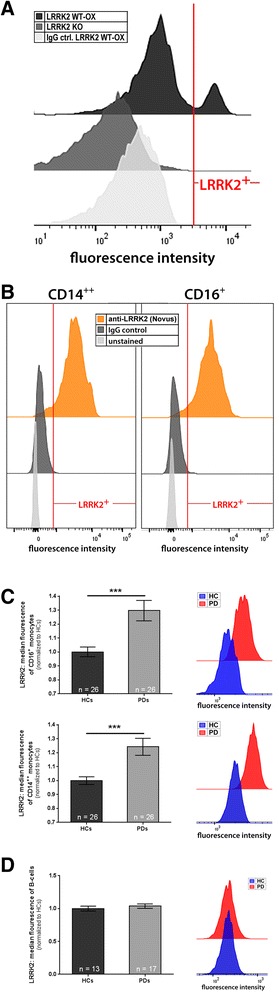

We set out to obtain a comprehensive picture of LRRK2 levels in circulating monocyte subpopulations as well as in lymphoid B-cells in PD patients. To determine the intracellular LRRK2 protein levels in the different immune cells we established a flow cytometry-based technique for intracellular LRRK2 staining. To verify the specificity of the anti-LRRK2 antibody used in this study [Novus Biologicals (NB300-268AF647)] isolated murine spleen cells from LRRK2 knockout (KO) mice [14] and mice overexpressing human wild-type (WT) LRRK2 (LRRK2 WT-OX mice) [17, 28] were processed, stained and analyzed as described in the supplementary material and method section (Additional file 1). While we found a highly LRRK2-positive population with the Novus antibody in spleen samples of LRRK2 WT-OX mice (black histogram Fig. 1a) no unspecific staining was found in LRRK2 KO mice (dark grey histogram Fig. 1a) or with the isotype control (IgG ctrl.) in spleen samples of LRRK2 WT-OX mice (light grey histogram Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

LRRK2 protein expression is significantly upregulated in monocytes from PD patients. a Spleen cells from LRRK2 KO and LRRK2 WT-OX mice were used to validate the suitable application of the rabbit-anti-LRRK2 antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor®647 from Novus Biologicals (NB300-268AF647) for intracellular flow cytometry analyses. The antibody showed a highly positive LRRK2 population in LRRK2 WT-OX cells (black histogram), whereas no LRRK2 staining was presented within KO cells (dark grey histogram), nor in LRRK2 WT-OX cells stained with the monoclonal rabbit isotype control (light grey histogram). The displayed experiment shows the fluorescence intensity of the different samples and is representative of three independent experiments. b Further validation experiments of intracellular LRRK2 staining for FACS analyses were performed with human whole blood samples. The human CD14++ and CD16+ monocyte subpopulations showed positive staining for LRRK2 [anti-LRRK2 (Novus); orange histogram], while the isotype control staining did not show any nonspecific binding (‘IgG control’; dark grey histogram). The displayed graphs are representative of three independent experiments. c Leukocytes from whole blood samples of healthy controls (HC; n = 26) and PD patients (PD; n = 26) were analyzed by flow cytometry to detect LRRK2 protein in the different monocyte subsets. CD16+ monocytes (upper panel) as well as CD14++ monocytes (lower panel) from PD patients displayed significantly higher LRRK2 expression compared to respective monocyte subsets from healthy controls. The histograms on the right are representative for the analyzed individuals and display the fluorescence intensity of the anti-LRRK2-AlexaFluor®647 antibody. The higher LRRK2 expression in monocytes of PD patients compared to healthy controls is demonstratively shown in these graphs. d Flow cytometric analyzes of CD19+ B-cells reveal no changes in the LRRK2 protein expression between healthy controls (n = 13) and PD patients (n = 17). The histograms on the right hand side represent the fluorescence intensity of the anti-LRRK2-AlexaFluor®647 antibody and show overlapping peaks which reveal no differences in LRRK2 expression. Error bars represent mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01; statistical significance was tested with non-parametric testing

We used a combination of our well established five-color FACS analysis strategy [5, 11] to distinguish “classical” CD14++CD16− (hereinafter referred to as CD14++) monocytes and “non-classical” CD14dimCD16+ (hereinafter referred to as CD16+) monocytes together with the intracellular LRRK2 staining. We found that both monocyte subpopulations were LRRK2 positive (orange histograms Fig. 1b), while the IgG and unstained controls did not show any significant staining (dark and light grey histograms Fig. 1b). Strikingly, we found significantly higher LRRK2 protein levels in CD16+ monocytes (upper panel Fig. 1c) as well as in CD14++ monocytes (lower panel Fig. 1c) of PD patients (n = 26; mean age 71.0 years) compared to age- and sex matched healthy controls (n = 26; mean age 68.7 years). Of note, probands with confounding factors affecting the immune system were excluded from all experiments (a detailed description of the proband cohort can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1). Similar results of elevated LRRK2 levels in monocytes from PD patients were also confirmed with two additional monoclonal anti-LRRK2 antibodies from abcam (MJFF5 (68–7) and UDD3 30(12)) (Additional file 2).

Since monocytes only represent ~ 6–12% of PBMCs [2] we also asked whether endogenous LRRK2 levels are altered in the remaining cell population predominantly comprising lymphocytes. T cells are devoid of LRRK2 [29], we thus focused on studying LRRK2 levels in B-cells of PD patients and healthy controls. Of note, we observed a significant reduction in the number of B-cells which has also been described earlier [21, 26] (data not shown). However, as demonstrated in Fig. 1d we did not detect altered LRRK2 protein levels in CD19+ B-cells between PD patients (n = 13; mean age 68.1 years) and controls (n = 17; mean age 71.4 years), indicating that LRRK2 levels are specifically increased in monocytes of PD patients. Our findings may explain previous results showing no increase in LRRK2 protein levels in PD patients’ PBMCs [7] since the increase of LRRK2 protein in monocytes may be masked by unchanged LRRK2 levels in B-cells.

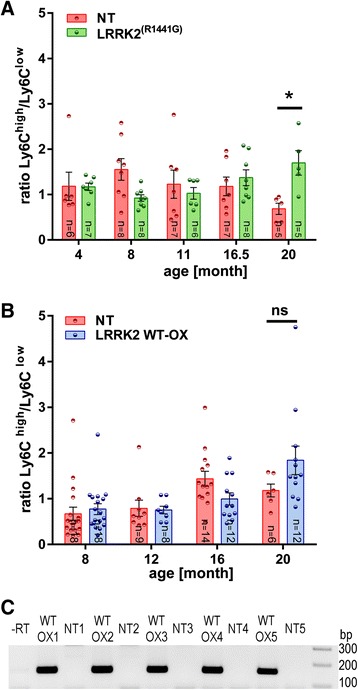

Previously, we have shown a dysregulation of monocyte subpopulations in the peripheral blood of PD patients [11]. Having now found that LRRK2 levels are elevated in PD monocytes, we next asked whether this LRRK2 increase might be involved in monocyte subtype dysregulation. Consequently, we assessed monocyte subpopulations in a LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mouse model overexpressing the mutant form of human LRRK2, recapitulating main features of Parkinson’s disease [17]. In mice CD14++ monocytes correspond to Ly6Chigh monocytes and CD16+ monocytes to Ly6Clow monocytes [15]. Using six-color flow cytometry [3, 8] LRRK2(R1441G) mice showed a marked age-dependent increase in the ratio of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocytes (Fig. 2a) compared to non-transgenic littermates which was most prominent at 20 month of age. Also in LRRK2 WT-OX mice we found a trend for an increase in the ratio of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocytes, although statistical significance was not reached (Fig. 2b). To additionally control that LRRK2 overexpression was persistent in PBMCs from LRRK2 WT-OX mice we performed RT-PCR and found a robust human LRRK2 expression in PBMCs from LRRK2 WT-OX mice but not in non-transgenic (NT) littermates (Fig. 2c), further strengthening the contribution of LRRK2 in shifting monocyte subpopulations in LRRK2 overexpressing mice.

Fig. 2.

Differences in the monocyte subset ratio of human LRRK2 overexpressing mice. a, b Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow monocyte subsets of mouse models for PD were analyzed by six-color flow cytometry. a A significant increase in the ratio of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocyte subsets was detected in 20 month old mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice in comparison to NT littermates. b A trend of an increasing ratio of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocytes of LRRK2 WT-OX mice compared to NT littermates were identified in 20 month old animals. Error bars represent mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05; ns: not significant; statistical significance was tested with 2way ANOVA (c) Murine PBMCs were isolated from whole blood samples and isolated RNA was transcribed into cDNA. PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose-gel. A band with 153 bp represent human LRRK2 and is only detected in PBMCs from LRRK2 WT-OX mice and not in NT littermates; −RT: negative reverse transcription control, NT: non-transgenic

In summary, we found elevated LRRK2 levels in CD14++ and CD16+ monocyte subsets of PD patients, but not in patients’ B-cells. Furthermore, similar to the dysregulation of monocyte subpopulations found in PD patients [11], a dysregulation of monocyte subpopulations was detected in LRRK2 overexpressing mice. Our results add to the growing body of evidence that LRRK2 plays an important role not only in neuronal cells but also in immune cells. LRRK2 has been implicated in aspects of monocyte function including monocyte maturation [29], adhesion, migration, and inflammation [18, 19]. Furthermore, LRRK2 is hierarchically clustered in the tyrosine-kinase like superfamily nearby kinases that are important for inflammatory signaling in immune activation [31]. Moreover, LRRK2 is supposed to function as a stress response kinase since inhibition of LRRK2 in innate immune cells attenuates pro-inflammatory signaling in response to TLR4 activation [19]. During bacterial phagocytosis, LRRK2 translocates near bacterial membranes, and knockdown of LRRK2 interrupts ROS production during phagocytosis and diminishes destruction of intracellular bacteria [9]. LRRK2 is not only found in different immune cells but becomes further upregulated upon exposure to different pathological stimuli like interferon γ (IFNγ) [9], microbial structures [lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] [10, 13] or viral particles [13]. Our current observation that LRRK2 levels are elevated in monocytes of PD patients establishes a compelling link between a specific role of LRRK2 in immune cells and their contribution to PD pathogenesis. Together with the recent study by Speidel et al. demonstrating a reduction in the non-classical CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation in PD LRRK2 mutant cells [25] our study forms strong evidence for the involvement of LRRK2 in PD monocyte dysregulation. Our current study also supports the idea that PD monocytes are in a pro-inflammatory predisposition as described earlier [11] and it might be that together with the co-occurrence of “second hits” like environmental cues or CNS factors triggering the peripheral immune system LRRK2 might be upregulated in monocytes. Together with our findings on a LRRK2-dependent dysregulation of monocytes in a PD mouse model, these results strengthen the idea of a central role of LRRK2 in immune cells and its contribution in peripheral inflammation in PD. Clearly, more studies are needed to determine the role of elevated LRRK2 levels in PD monocytes, its role in dysregulation of monocyte subpopulations and in modulating inflammatory cytokine production. Moreover, the signaling pathways and the pathogenic stimulus actually leading to LRRK2 upregulation need to be determined. Our findings establish a basis for future studies on LRRK2-dependent monocyte dysregulation, peripheral inflammation and its contribution to PD pathogenesis.

Additional files

Supplementary materials and methods. (PDF 1185 kb)

LRRK2 protein expression is significantly upregulated in monocytes from PD patients. (PDF 303 kb)

Acknowledgements

The excellent technical assistance of Ramona Bück is gratefully acknowledged. Furthermore, we thank Dorothea Hüske and Susanne Milde for the organization and collection of blood samples.

Funding

This research was supported by funds from the Baustein Program Medical Faculty Ulm University (KMD, VG), Charcot Foundation (LZ, ACL, JHW), Juniorprofessorship Program Baden-Württemberg (MK, KMD), the Boehringer Ingelheim Ulm University Biocenter (KMD, CB) and the Thierry Latran Foundation (LZ, JHW).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Authors’ contributions

CB, LZ and VG performed experiments and analyzed the data. CB, LZ, VG, WPR, DB and JK helped with sample collection. WPR, DB and JK interpreted patients’ clinical data and defined patient cohorts based on PD scores as well as considering confounding immune factors. HLM, PB and FG isolated spleen cells and collected blood samples from LRRK2 KO and LRRK2R1441G mice, respectively. HLM, FG, JK, ACL and JHW gave intellectual input to the study. CB and KD designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human samples

All human experiments were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ulm University, Germany. All study volunteers gave informed written consent to participate in the study. PD patients as well as healthy probands were recruited at the Universitäts- und Rehabilitationskliniken Ulm, Germany (RKU).

Murine samples

All mouse experiments with the LRRK2 WT-OX FVB/N mice were performed in accordance with the German Law for the Protection of Animal Welfare (Tierschutzgesetz) and in accordance to the guidelines of the animal research center at the University of Ulm, Germany.

All experiments with the LRRK2R1441G BAC transgenic FVB/N mice were approved by the appropriate institutional governmental agency (Regierungspräsidium Tübingen, Germany) and performed in accordance with the European Convention for Animal Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

All animal procedures with the LRRK2 KO C57BL/6 mice were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Jacksonville, USA) and were in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Abbreviations

- HC

Healthy control

- IFNγ

Interferon γ

- KO

Knock out

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- LRRK2

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- NT

Non-transgenic

- OX

Overexpressing

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- RKU

Universitäts- und Rehabilitationskliniken Ulm

- WT

Wild type

References

- 1.Alegre-Abarrategui J, Christian H, Lufino MM, Mutihac R, Venda LL, Ansorge O, et al. LRRK2 regulates autophagic activity and localizes to specific membrane microdomains in a novel human genomic reporter cellular model. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4022–34. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autissier P, Soulas C, Burdo TH, Williams KC. Evaluation of a 12-color flow cytometry panel to study lymphocyte, monocyte, and dendritic cell subsets in humans. Cytometry A. 2010;77:410–9. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliederhaeuser C, Grozdanov V, Speidel A, Zondler L, Ruf WP, Bayer H, et al. Age-dependent defects of alpha-synuclein oligomer uptake in microglia and monocytes. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;131:379–91. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, O'Reilly EJ, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:90–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Fonzo A, Wu-Chou YH, Lu CS, van Doeselaar M, Simons EJ, Rohe CF, et al. A common missense variant in the LRRK2 gene, Gly2385Arg, associated with Parkinson’s disease risk in Taiwan. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:133–8. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzamko N, Chua G, Ranola M, Rowe DB, Halliday GM. Measurement of LRRK2 and Ser910/935 phosphorylated LRRK2 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3:145–52. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao L, Brenner D, Llorens-Bobadilla E, Saiz-Castro G, Frank T, Wieghofer P, et al. Infiltration of circulating myeloid cells through CD95L contributes to neurodegeneration in mice. J Exp Med. 2015;212:469–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardet A, Benita Y, Li C, Sands BE, Ballester I, Stevens C, et al. LRRK2 is involved in the IFN-gamma response and host response to pathogens. J Immunol. 2010;185:5577–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillardon F, Schmid R, Draheim H. Parkinson’s disease-linked leucine-rich repeat kinase 2(R1441G) mutation increases proinflammatory cytokine release from activated primary microglial cells and resultant neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 2012;208:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grozdanov V, Bliederhaeuser C, Ruf WP, Roth V, Fundel-Clemens K, Zondler L, et al. Inflammatory dysregulation of blood monocytes in Parkinson’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habig K, Gellhaar S, Heim B, Djuric V, Giesert F, Wurst W, et al. LRRK2 guides the actin cytoskeleton at growth cones together with ARHGEF7 and Tropomyosin 4. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:2352–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakimi M, Selvanantham T, Swinton E, Padmore RF, Tong Y, Kabbach G, et al. Parkinson’s disease-linked LRRK2 is expressed in circulating and tissue immune cells and upregulated following recognition of microbial structures. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:795–808. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinkle KM, Yue M, Behrouz B, Dachsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Bowles EE, et al. LRRK2 knockout mice have an intact dopaminergic system but display alterations in exploratory and motor co-ordination behaviors. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R, et al. Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood. 2010;115:e10–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubo M, Kamiya Y, Nagashima R, Maekawa T, Eshima K, Azuma S, et al. LRRK2 is expressed in B-2 but not in B-1 B cells, and downregulated by cellular activation. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;229:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Liu W, Oo TF, Wang L, Tang Y, Jackson-Lewis V, et al. Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:826–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moehle MS, Daher JP, Hull TD, Boddu R, Abdelmotilib HA, Mobley J, et al. The G2019S LRRK2 mutation increases myeloid cell chemotactic responses and enhances LRRK2 binding to actin-regulatory proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:4250–67. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moehle MS, Webber PJ, Tse T, Sukar N, Standaert DG, Desilva TM, et al. LRRK2 inhibition attenuates microglial inflammatory responses. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1602–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5601-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pirttila T, Mattinen S, Frey H. The decrease of CD8-positive lymphocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1992;107:160–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(92)90284-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reale M, Iarlori C, Thomas A, Gambi D, Perfetti B, Di Nicola M, et al. Peripheral cytokines profile in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Mizuta I, Hirota Y, Ito C, Kubo M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon-Sanchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speidel A, Felk S, Reinhardt P, Sterneckert J, Gillardon F. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 influences fate decision of human monocytes differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens CH, Rowe D, Morel-Kopp MC, Orr C, Russell T, Ranola M, et al. Reduced T helper and B lymphocytes in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;252:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stypula G, Kunert-Radek J, Stepien H, Zylinska K, Pawlikowski M. Evaluation of interleukins, ACTH, cortisol and prolactin concentrations in the blood of patients with parkinson’s disease. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1996;3:131–4. doi: 10.1159/000097237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The-Jackson-Laboratory. https://www.jax.org/strain/009610. Accessed April 5th 2016

- 29.Thevenet J, Pescini Gobert R, Hooft Van Huijsduijnen R, Wiessner C, Sagot YJ. Regulation of LRRK2 expression points to a functional role in human monocyte maturation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Yan MH, Fujioka H, Liu J, Wilson-Delfosse A, Chen SG, et al. LRRK2 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function through direct interaction with DLP1. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1931–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, Andrabi SA, Li X, Dikeman D, et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:223–32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials and methods. (PDF 1185 kb)

LRRK2 protein expression is significantly upregulated in monocytes from PD patients. (PDF 303 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.