Abstract

The S100 proteins are a unique class of EF-hand Ca2+ binding proteins distributed in a cell-specific, tissue-specific, and cell cycle-specific manner in humans and other vertebrates. These proteins are distinguished by their distinctive homodimeric structure, both intracellular and extracellular functions, and the ability to bind transition metals at the dimer interface. Here we summarize current knowledge of S100 protein binding of Zn2+, Cu2+ and Mn2+ ions, focusing on binding affinities, conformational changes that arise from metal binding, and the roles of transition metal binding in S100 protein function.

Keywords: S100 Proteins, Zinc, Manganese, Copper

INTRODUCTION

S100 proteins are an important class of EF-hand calcium binding proteins distinguished by unique dimeric structures and functions both inside and outside cells (Donato, 2003; Donato et al., 2013; Nelson and Chazin, 1998; Potts et al., 1995; Zackular et al., 2015). Their intracellular functions are primarily regulatory in nature, mediated by interactions with target proteins involved in a range of processes including proliferation, differentiation, and inflammation. S100 proteins are also released or secreted from cells, where they activate a variety of cell surface receptors in both an autocrine and a paracrine manner. Several S100 proteins serve as damage-associated molecular pattern recognition factors (DAMPS) in the adaptive and innate immune systems (Donato et al., 2013), and are known to be recruited to sites of inflammation (Striz and Trebichavsky, 2004). The S100A8/S100A9 heterodimer (termed calprotectin or CP) is the most-well studied of the S100 proteins in the immune response; it has been shown to function in the response to a range of microbial pathogens via a mechanism termed “nutritional immunity”, inhibiting growth by sequestering nutrient transition metals Zn2+ and Mn2+ (Zackular et al., 2015). The binding of transition metals by S100 proteins was first characterized over 30 years ago (Baudier et al., 1982, 1984). With a specific functional role for transition metal binding by S100 proteins now emerging, it is an appropriate time to review the field. In this monograph, we will focus on the wide range of affinities for these ions, the structural consequences of transition metal binding, and how transition metal binding modulates function.

S100 proteins were first identified over five decades ago from bovine brain and are named on the basis of their solubility in 100% ammonium sulfate (Moore, 1965). To date, there are 25 members in the human proteome and homo-logues have only been identified only in vertebrates, suggesting that they are “evolutionary newcomers” (Schaub and Heizmann, 2008). Unlike other EF-hand proteins, they exhibit cell-type, tissue-specific, and cell cycle-dependent expression along with differential gene regulation (Schäfer and Heizmann, 1996). S100 proteins are involved in a wide range of cellular functions including intracellular calcium buffering, modulation of enzyme activities, energy metabolism, and regulation of cell growth, cytoskeleton development and differentiation (Schaub and Heizmann, 2008). While EF-hand proteins appear to have evolved to transduce intracellular Ca2+ signals, S100 proteins have the unique ability to also function in the extracellular milieu. Some S100 proteins play essential roles in signaling and secretion of ligands for receptor binding (Donato et al., 2013), modulated in certain cases by post-translational modifications and transition metal binding (Moroz et al., 2009a; van Dieck et al., 2009). S100 proteins are also part of the innate immune response to bacterial pathogens (Zackular et al., 2015). In the clinic S100 proteins serve as biomarkers for cardiomyopathy (S100A1), psoriasis (S100A7), chronic inflammation disorders and inflammatory bowel disease (S100A8/A9), and several cancers (S100A2/A4/A6) (Heizmann et al., 2002; Schäfer and Heizmann, 1996).

S100 PROTEIN STRUCTURE AND BIOCHEMISTRY

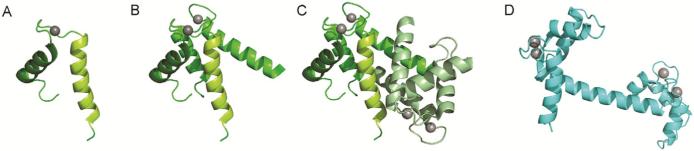

The fundamental organization for all EF-hand Ca2+ binding proteins is a four-helix bundle domain containing a pair of helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs (Figure 1). S100 proteins, the largest subgroup within the EF-hand superfamily, are comprised of an S100-specific N-terminal EF-hand with a 14-residue Ca2+ binding loop, and a C-terminal EF-hand with a canonical 12-residue Ca2+ binding loop (Bunick et al., 2004). They are also distinguished from other EF-hand proteins (e.g. calmodulin) by obligate formation of dimers (Figure 1) (Potts et al., 1996); all function as dimers or higher order oligomers except for calbindin D9k (S100G), which is a shortened, ancestral member of the sub-family that lacks the ability to dimerize. Higher order oligomerization of S100 proteins is non-covalent and can be promoted by low affinity metal binding sites at the exterior surface of the dimer. Both Ca2+ and transition metals (particularly Zn2+) have been shown to stimulate oligomerization in vitro, and crystal structures have revealed a range of oligomeric states. However, the relevance of oligomerization of S100 proteins in vivo remains controversial except in situations where protein and metal concentrations are sufficiently high to match the conditions of the in vitro experiments. That stated, the high (millimolar) concentration of Ca2+ in the extracellular space implies that those S100 proteins whose oligomerization is promoted by Ca2+ may exist in higher order oligomeric states.

Figure 1.

Structural features of S100 proteins. Ribbon diagrams of (A) an EF-hand motif, (B) an EF-hand domain, (C) the integration of two EF-hand domains into an S100 dimer, and (D) the alternate arrangement of two EF-hand domains in a prototypical EF-hand Ca2+ signal modulator. S100A12 was selected as the representative member of the S100 proteins and panels A, B and C were created using the Ca2+-loaded protein (PDB entry 1E8A). Panel D was created using Ca2+-loaded calmodulin (PDB entry 1CLL). The compact nature of the S100 homodimer relative to calmodulin implies a fundamentally different structural mechanism for transduction of Ca2+ signals.

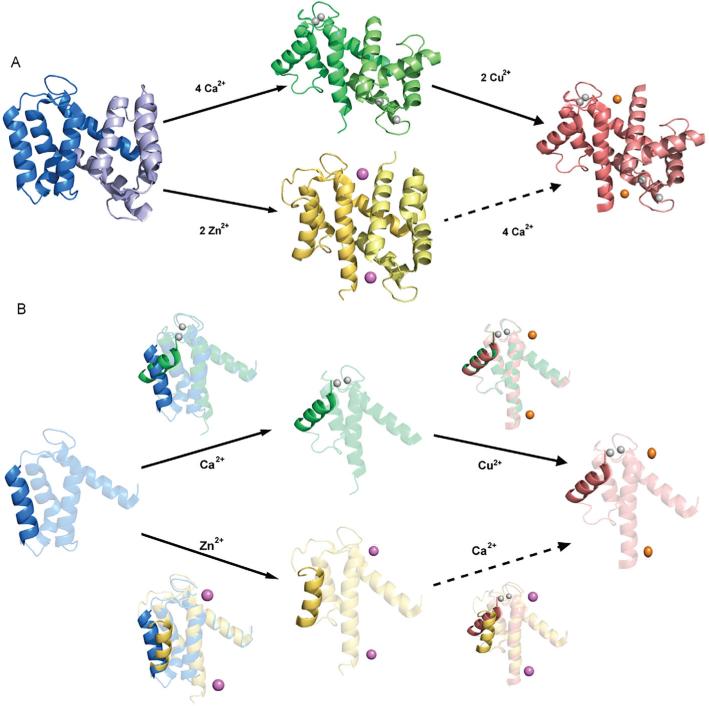

Like other EF-hand proteins, S100 proteins respond to Ca2+ signals by undergoing conformational changes upon ion binding, although the conformational changes are more modest relative to canonical EF-hand Ca2+ sensor proteins such as calmodulin (Nelson and Chazin, 1998; Nelson et al., 2002). Despite large variations in amino acid sequence (between 20% and 60% identity), the Ca2+-induced conformational change in all S100 proteins involves a significant shift in the orientation of Helix III (Figure 2) (Maler et al., 2002). Like other EF-hand Ca2+ sensors, this conformational change results in exposure of a hydrophobic patch that serves as the key factor driving binding of targets. Although they have very similar structural architectures, S100 proteins interact with a diverse set of cellular targets. This variability is accomplished by the fine-tuning within the target binding site of each S100 protein (Bhattacharya et al., 2004), in combination with their distinct cell-type, tissue-specific, and cell cycle-dependent expression. Current understanding of the cooperativity of Ca2+ binding and the structural rearrangements induced by Ca2+ binding have been reviewed in more detail elsewhere (Chazin, 2007; Ikura, 1996; Nelson and Chazin, 1998). Here we will focus on the unique ability of S100 proteins to bind transition metals in binding sites distinct from their Ca2+ binding sites (Heizmann and Cox, 1998), and the corresponding effects on structure, function and biochemical properties.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional structure of S100A12 and conformational changes induced by Ca2+ and transition metals. A, Ribbon diagrams of the apo, (Ca2+)4, (Zn2+)2, and (Ca2+)4, (Cu2+)2, states. B, Comparison of single sub-units to emphasize the differences in the packing of Helix III in different states. This reveals that the consequences of binding Ca2+ are much greater than those of binding transition metals. Images generated in pymol (DeLano, 2002) using coordinates deposited in the PDB for apo (2WCF), (Ca2+)4 (1E8A), (Zn2+)2 (2WC8) and (Ca2+)4, (Cu2+)2 (1ODB).

BINDING OF ZINC

The first report of Zn2+ binding to an S100 protein (S100B) was over thirty years ago (Baudier et al., 1984). Since that time binding of Zn2+ has been reported for S100A1, S100A2, S100A3, S100A5, S100A6, S100A7, S100A8/A9, S100A12, S100A16 and S100B (Table 1). Zn2+ binding S100 proteins can be classified into two categories: His-rich and Cys-rich. Sequence alignments, spectroscopic analysis, site-directed mutagenesis and high-resolution structures revealed a conserved binding motif for the proteins with His-rich sites (S100A6, S100A7, S100A8/A9, S100A12, S100A15, S100B), with 4 His residues, or 3 His and 1 Asp residues, at the dimer interface (Figure 3). The first Zn2+-bound structure was determined for S100A7 (Brodersen et al., 1999), and several additional Zn2+-bound structures from the His-rich group have been reported since. Since the proteins are dimers, each protein binds two Zn2+ at the two symmetrically disposed sites (Figure 2).

Table 1.

S100 protein transition metal binding affinities

| Protein | Zn2+ Kd |

Mn2+ Kd |

Cu2+ Kd |

|---|---|---|---|

| S100A1 | <Kd (S100B) | ||

| Trp fluorescence (Baudier, et al., 1986) | |||

| S100A2 | 49 nmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| 25 nmol L−1 (+Ca) | |||

| Competition with Zn chelator (Koch et al., 2007) | |||

| S100A3 | 4 nmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| Competition with Zn chelator (Fritz, et al., 2002) | |||

| S100A5 | 1–3 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | 5 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | |

| Equilibrium gel filtration (Schäfer, et al., 2000) | Equilibrium gel filtration (Schäfer et al., 2000) | ||

| S100A6 | 100 nmol L−1 (+Ca) | ||

| Fluorescence spectroscopy (Kordowska, et al., 1988) | |||

| S100A7 | 100 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| Equilibrium dialysis (Vorum, et al., 1996) | |||

| S100A8/A9 | 3 nmol L−1 (+Ca) Site1 (Mn/Zn) | 6 nmol L−1 (+Ca) Site1 (Mn/Zn) | |

| 8 nmol L−1 (+Ca) Site2 (Zn only) | ITC (Damo, et al., 2013) | ||

| ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) (Damo, et al., 2013) | |||

| Kd1 ≤ 10 pmol L−1 (excess Ca) | Kd1=200 nmol L−1 (excess Ca) | ||

| Kd2 ≤ 240 pmol L−1 (excess Ca) | Kd2=20 μmol L−1 (excess Ca) | ||

| Fluorescent competition (Brophy, et al., 2012) | EPR titrations (Hayden et al., 2013) | ||

| S100A12 | 2 and 100 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| Fluorescence spectroscopy (Moroz, et al., 2009) | |||

| S100A13 | 12 and 55 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| 62 and 120 μmol L−1 (+Ca) | |||

| ITC (Sivaraja, et al., 2006) | |||

| S100A16 | ~ 25 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | ||

| Equilibrium gel filtration (Sturchler et al., 2006) | |||

| S100B | 94 nmol L−1 (+Ca) | 71 μmol L−1 (−Ca) | Average 0.46 μmol L−1 (−Ca) |

| ITC (Wilder et al., 2003) | 55.9 μmol L−1 (+Ca) | Equilibrium filtration (Nishikawa et al., 1997) | |

| EPR and NMR (Rustandi et al., 1988) |

Figure 3.

Alignments of S100 proteins containing transition metal binding sites. Structure based sequence alignment of S100 proteins from the His-rich (upper panel) and Cys-rich (lower panel) categories. Conserved residues in His-rich sites are highlighted with teal background, and those in Cys-rich sites in red background. Note the high degree of conservation in the His-rich proteins compared to the Cys-rich proteins. The alignments were generated using PROMALS3D (Pei et al., 2008).

The S100 proteins capable of binding Zn2+ ions have affinities ranging from Kd=4 nmol L−1 (S100A3) to 100 μmol L−1 (S100A7) (Table 1). Direct comparisons among the reported affinities are not straightforward because the methods used and experimental conditions vary significantly. Importantly, although the majority of the Kd values fall within the μmol L−1 range, Zn2+ concentrations inside and outside cells are low (e.g. 2–10 nmol L−1 in the cytoplasm). Hence, the biological relevance of the binding of Zn2+ has yet to be established for most S100 proteins. Another significant factor in correlating in vitro measurements to functional context is the energetic coupling of interactions with metal co-factors and targets. This issue is well recognized for EF-hand proteins in the case of the substantial differences in Ca2+ affinity measured in the absence and presence of target proteins. Thus, an interplay between Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding to S100 proteins is expected. In fact, Zn2+ binding has been reported to raise the Ca2+ affinity of S100B by a factor of 10 and of S10012 by ~1500 fold (Dell'Angelica et al., 1994; Moroz et al., 2011), to lower the Ca2+ affinity of S100A2 (Koch et al., 2007), and to have no effect on S100A5 (Schäfer et al., 2000).

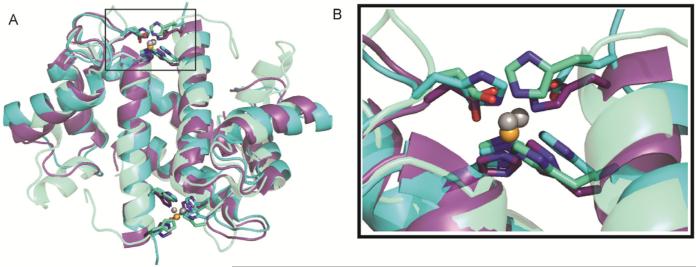

The effects of Zn2+ binding on the structure of S100 proteins are in general rather modest. The basic dimeric architecture observed for the apo and Ca2+-loaded states is retained and overall the structures are very similar (all Cα RMSDs (root-mean-square deviations)<1.0 Å) (Figure 2A). The structural changes induced by the binding of Ca2+ are substantially larger than the structural changes induced by the binding of Zn2+, i.e. Zn2+-bound apo proteins are more similar to the apo state than to the Zn2+-bound Ca2+-loaded state, and Zn2+-bound Ca2+-loaded proteins are more similar to the Ca2+-loaded state than to the Zn2+-bound apo state (Figure 2B). Detailed comparative analyses for structural differences between all states are possible for S100A7, for which structures have been determined in the apo, Ca2+-loaded, and Ca2+, Zn2+-loaded states, and for S100A12, for which structures have been determined in the apo, Ca2+-loaded, Zn2+-loaded, and Ca2+,Cu2+-loaded states. (The great similarity of Zn2+ and Cu2+ sites is discussed below in “Binding of copper”) As seen in the Zn2+-loaded structures of S100A7 and S100A12, two Zn2+ ions are bound at the symmetrically disposed sites (Figure 4), coordinated by three His N2 atoms (His17, His86, His90) and an aspartate side chain (Asp24) (Figure 4B) (Brodersen et al., 1999; Leon et al., 2009). In all cases, the primary effect of Zn2+ is to alter the orientation of Helix III (Figure 2B). Interestingly, Zn2+-binding results in poor electron density for residues 62–67 in S100A12, even though these are well defined in the structure of the apo state (Moroz et al., 2009a). This led to the proposal that flexibility in this loop region may be induced by Zn2+, and thereby facilitate the ~1500-fold increase in the affinity of S100A12 for Ca2+.

Figure 4.

Structural similarity of tetrahedral zinc and copper binding sites in S100 proteins. A, Overlay of the structures of (Ca2+)4, (Zn2+)2-S100A7 (light green), (Ca2+)4, (Zn2+)2-S100B (teal) and (Ca2+)4,(Cu2+)2-S100A12 (purple) showing that the transition metal ions are chelated in a similar manner by side chains in the same position in the sequence. B, Zoom in on the tetrahedral Zn2+ and Cu2+ sites showing the similar spatial disposition of the 3 His and 1 Asp chelating side chains. The Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions are colored gray and orange, respectively. Images generated in pymol (DeLano, 2002) using PDB coordinates deposited for (Ca2+)4, (Zn2+)2-S100A7 (2PSR), (Ca2+)4, (Zn2+)2-S100B (3D0Y), and (Ca2+)4, (Cu2+)2-S100A12 (1ODB).

The binding of Zn2+ has been extensively studied for S100B, most notably in conjunction with the p53 tumor suppressor protein (Lin et al., 2004). S100B has high affinity for Zn2+ (Kd ~90 nmol L−1). NMR spectroscopy and site directed mutagenesis indicated that Zn2+ binding occurs in a similar manner to other S100 proteins with His-rich transition metal binding sites, namely His15/His25 from one subunit and His85/His89 from the other subunit. However, Zn2+ binding to S100B causes a more pronounced kink in Helix IV than in S100A7 and S100A12 (Wilder et al., 2005). Zn2+ binding has been shown to increase the affinity for target peptides over the effect of Ca2+ alone (Wilder et al., 2003). Structural coupling of the Zn2+ and target binding sites has been found, and this information has been incorporated into the design of S100B inhibitors of the interaction with targets such as p53. Co-crystal structures with pentamidine, an S100B inhibitor known to bind in the target binding site, were determined for both the Ca2+- and Ca2+, Zn2+-loaded states (Charpentier et al., 2008; Charpentier et al., 2009). These studies motivated the generation of new inhibitors engineered to disrupt the Zn2+-binding residues and Zn2+-induced conformational changes in S100B (Cavalier et al., 2014).

The role of oligomerization in the function of S100 proteins has been vigorously debated. There is ample evidence of Ca2+- and Zn2+-induced oligomerization in vitro including a number of crystal structures with high order oligomerization states (Moroz et al., 2002, 2009a; Ostendorp et al., 2007) and a mass spectrometry study of Zn2+-induced tetramerization of CP (Vogl et al., 2006). However, there is very little evidence of the functional significance of oligomerization from experiments in cells; this is an area that is in great need of further investigation. A role for oligomerization of S100 proteins is most likely in association with the extracellular functions of S100 proteins as activators of cell surface receptors (Malashkevich et al., 2010; Moroz et al., 2009a; Ostendorp et al., 2011, 2007). The most well studied of these receptors is receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which has been shown to bind several S100 proteins at the cell surface and elicit an intracellular response via the NF-κB signaling pathway. A role for Zn2+ in the interaction of S100A7 and S100A15 with RAGE has been proposed (Murray et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2008).

The Cys-rich Zn2+ binding S100 proteins (S100A2, S100A3, S100A4) are much less studied than the His-rich group (Moroz et al., 2011). One challenge is the absence of a conserved motif evident from alignment of these proteins (Figure 3). The consensus view is that the Cys-rich sites coordinate Zn2+ ions with either 4 Cys residues or 3 Cys and 1 His residue (Moroz et al., 2011). A second challenge is that Cys-rich sites will be susceptible to redox reactions that disrupt disulfides and modulate Zn2+-binding. Obtaining high resolution X-ray data on the Cys-rich Zn2+-binding S100 proteins is difficult due to improper folding during in vitro bacterial overexpression. In fact, the majority of S100A2 and S100A4 structures were determined with Cys residues mutated to facilitate protein production. The protein production obstacle was overcome for S100A3 by producing the protein from insect cells, which promotes proper disulfide formation and folding (Kizawa et al., 2013a, b). Crystallization of S100A3 produced in this manner identified two disulfide bonds not previously identified. These disulfides apparently play a critical structural role, as disruption of either disulfide significantly affected the Ca2+ affinity (Unno et al., 2011). Unfortunately, electron density for Zn2+ ions was too weak to formally assign their presence in the structure. However, a single Cys-rich Zn2+ site could be readily modeled, and Zn2+ binding was proposed to be important for folding and formation of the critical disulfide bonds in S100A3. Since the majority of analyses in the past 15 years utilized recombinant protein expressed in E. coli, future studies using proteins produced from eukaryotic expression systems may enhance understanding of Zn2+ binding to S100 proteins from the Cys-rich group.

BINDING OF COPPER

Due to their similar chemical properties, copper is anticipated to bind to most zinc binding sites in proteins. It was therefore natural to examine the binding of copper (Cu2+) to S100 proteins when Zn2+ binding was first noted for S100B (Nishikawa et al., 1997). In that report, four Cu2+ ions were identified per S100B dimer with an average dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.46 μmol L−1. However, subsequent structure-based alignments predicted that there are only two high affinity sites and that the two others are weak non-specific sites (Nishikawa et al., 1997). Ion competition experiments demonstrated that the Cu2+ ions could be displaced by Zn2+, but not Ca2+. Thus, as expected, the binding of Cu2+ by S100 proteins closely resembles binding of Zn2+, with a few noticeable exceptions.

Important insight into binding of Cu2+ by S100 proteins was provided by the X-ray crystal structure of Ca2+, Cu2+-S100A12 (Moroz et al., 2003). The overall conformational change induced by the binding of Cu2+ is very small; the Cα RMSD of the Ca2+ versus the Ca2+, Cu2+ state is 0.35 Å. Interestingly, both the apo and Ca2+, Cu2+-bound states have well defined electron density out to Lys90, but His87-Lys90 is disordered when only Ca2+ is bound (Moroz et al., 2003). The Cu2+ ion is bound in a canonical Cu2+ site (3 His residues along with either an oxygen or sulfur containing residue), with coordination by His15 and Asp25 from one subunit and His85 and His89 from the other subunit, identical to the coordination of Zn2+. In fact, Ca2+, Cu2+ and Ca2+, Zn2+ structures are very similar even when comparing between different S100 proteins (Figure 4): the Cα RMSD between Ca2+, Cu2+-S100A12 and Ca2+, Zn2+-S100A7 is only 0.72 Å, and for Ca2+, Zn2+-S100B only 0.42 Å (Charpentier et al., 2008). The great similarity in the structures of the Cu2+ and Zn2+-loaded protein implies that Cu2+ will bind to the Zn2+ sites in other S100 proteins (Moroz et al., 2003, 2009b).

The structural consequences of Cu2+ binding to S100A13 have been investigated using solution NMR (Arnesano et al., 2005). Comparisons between apo, Ca2+-loaded and Ca2+, Cu2+-loaded S100A13 revealed Cu2+ causes an additional, minor opening of the Helix III-IV interface relative to the Ca2+-loaded state. The binding site has several unique characteristics compared to other S100 proteins, including the location of the site, as well as the ligand coordination and solvent accessibility to the Cu2+ ion. NMR titrations of Ca2+-S100A13 with paramagnetic Cu2+ ions were used to propose Glu4, Glu8, Glu11, and His48 as the Cu2+-chelating side chains. These correlated with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies that assigned the Cu2+ coordination as pseudo-tetragonal with nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms. An unexpected aspect of their analysis was that the Cu2+ ions are completely exposed to solvent, unlike the typical transition metal sites that are buried within the S100 proteins (Arnesano et al., 2005). The authors suggested that exposure of the metal may help regulate the interaction of S100A13 with target proteins, but no data was provided in support of this speculation.

Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions have been proposed to induce conformational changes in S100 proteins (e.g. (Vogl et al., 2006)), although the crystal structures described above and shown in Figure 4 reveal these changes are very modest. Nevertheless, Cu2+ binding has the potential to alter the structure of S100 proteins and therefore oligomerization and interactions with target proteins. Although Zn2+ induced oligomerization of S100 proteins has been explored in vitro, the sole study of the effect of Cu2+ reported no changes in oligomerization of the S100A8/S100A9 heterodimer (Vogl et al., 2006). The only study of the effect of Cu2+ on receptor binding revealed stimulation of the interaction of S100A4 with RAGE (Haase-Kohn et al., 2011). Although the dearth of information about the effects of Cu2+ on physical properties should be addressed, there is even greater urgency to establish if Cu2+ binding has any physiological role in S100 protein function.

BINDING OF MANGANESE

Manganese is an important transition metal in biological systems (Sigel and Sigel, 2000). It is a critical component in certain enzymatic processes (e.g. phosphorylation) and in the oxidative stress response. Recently, manganese regulation has been recognized for its essential role in contributing to the virulence of pathogenic organisms (reviewed in (Zackular et al., 2015)), with an explicit role played by the S100A8/S100A9 heterodimer, calprotectin (CP). As will be summarized below, high affinity binding of Mn2+ to S100 proteins is unique to CP.

All pathogenic organisms require essential nutrients from the host to survive and proliferate, including transition metals. A mechanism termed nutritional immunity, which involves sequestering the essential nutrients from the pathogen, is used by the host to fight infection. A role for transition metals besides Fe in nutritional immunity was first discovered when inductively coupled plasma mass spec-trometry (ICP-MS) analysis showed that there are distinct differences in the transition metal content in and around tissues infected with Staphylococcus aureus (Corbin et al., 2008). In particular, staphylococcal abscesses were found to be devoid of Zn2+ and Mn2+ ions. Proteomic imaging of the tissue revealed high concentrations of the S100A8 and S100A9 CP subunits surrounding the sites of infection. Subsequent work confirmed that CP, which is present in very large abundance in certain innate immune cells such as neutrophils, plays a critical role in the innate immune response to pathogens, functioning via the nutritional immunity mechanism through the high affinity binding and sequestration of Zn2+ and Mn2+ (Corbin et al., 2008; Zackular et al., 2015). Subsequent studies using CP knockout mice have demonstrated that CP inhibits growth from other pathogenic organisms, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus and Helicobacter pylori (Clark et al., 2016; Gaddy et al., 2014; Hood et al., 2012; Kehl-Fie et al., 2011, 2013).

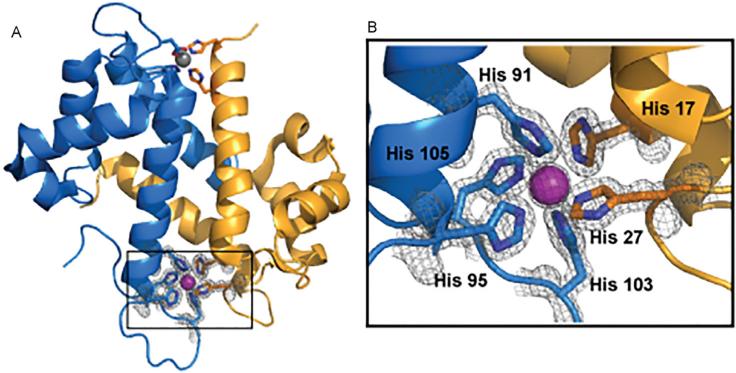

Based on the available information on the binding of Zn2+ to S100 proteins, it was assumed that Mn2+ bound to similar sites and completed its coordination shell with waters. Importantly, early studies showed that CP bound 2 equivalents of Zn2+ ions, but only one equivalent of Mn2+. This was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis studies that revealed Mn2+ binds to the 4-His site (His17 and His27 from S100A8, His91 and His95 from S100A9) (Kehl-Fie et al., 2011). Site directed mutagenesis experiments also showed that two His residues in the S100A9 C-terminal tail (His103, His105) are required for high affinity Mn2+ binding (Brophy et al., 2013; Damo et al., 2013). As noted above, there is energetic coupling of transition metal binding and Ca2+ binding; the Mn2+ affinity of CP under limited Ca2+ availability (Kd>550 nmol L−1) is weaker than in the presence of Ca2+ (Kd=194 nmol L−1) (Brophy and Nolan, 2015; Damo et al., 2013). The origin of this allosteric effect has yet to be established, although it is conceivable that binding of Ca2+ results in reorganization of the structure and/or dynamics of key side chains to better facilitate Mn2+ binding. Notably, the only known function of transition metal binding for CP is in the extracellular milieu where Ca2+ concentrations are very high (in the mmol L−1 range) and CP's Ca2+ sites will invariably be filled, so the physiological relevance of the difference in Mn2+ affinities in the absence and presence of Ca2+ remains uncertain.

The critical step forward in characterizing the binding of Mn2+ to CP was the determination of the crystal structure of (Ca2+)4, Mn2+-CP (Brophy et al., 2013; Damo et al., 2013; Gagnon et al., 2015) (Figure 5). Comparison with the (Ca2+)4-CP structure (Korndorfer et al., 2007) revealed there are no large conformational changes. The Cα RMSD between the two structures is 0.29 Å for the S100A8 subunit and 0.24 Å for the S100A9 subunit. Previous crystal structures of CP were disordered beyond His95 in the C-terminal tail; only with the addition of Mn2+ ions in the crystal structure was electron density out to Gly112 well defined. This correlates with the direct observation of chelation of the Mn2+ ion by the His103 and His105 side chains. Typically, Mn2+ is coordinated by 5 or 6 ligands. The Mn2+ site in CP is the only example of 6-His octahedral coordination of Mn2+ in the Protein DataBank (PDB). CP is the only member of the S100 protein group that is capable of high affinity binding of Mn2+ (Brophy et al., 2013; Brophy and Nolan, 2015; Damo et al., 2013); the crystal structure shows that this is due to the unique combination of the 4-His transition metal binding site at the heterodimer interface (Figure 5) and the His-rich C-terminal tail that is unique to S100A9.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional structure of calprotectin highlighting the unique manganese binding site. The S100A8 subunit is colored blue, the S100A9 subunit gold, and the Mn2+ ion purple. An additional low occupancy Mn2+ ion is shown in gray. Images generated in pymol (DeLano, 2002) using coordinates deposited in the PDB for (Ca2+)4, (Mn2+)-CP (4GGF).

BINDING OF OTHER TRANSITION METALS

Robust Zn2+ binding at the dimerization interface led to studies of the ability of S100 proteins to bind other first-row transition metals besides Mn2+ and Cu2+, but no significant affinities were observed (Fritz et al., 1998). A recent study reports that CP is capable of sequestering ferrous (Fe2+) iron from pathogenic growth media, in parallel to sequestration of Mn2+ and Zn2+ (Nakashige et al., 2015). However, the relevance of ferrous iron to the host-pathogen interaction has not been firmly established, and existing in vivo data do not support a role for CP in the sequestration of iron as a defense strategy against infection (Corbin et al., 2008; Damo et al., 2013). Sub-picomolar affinity for Fe2+ was reported, with coordination via an uncommon 6-His coordination assigned based on Mössbauer spectroscopy (Nakashige et al., 2015) that presumably corresponds to the unique Mn2+ binding site in CP. If such very high CP affinity for Fe2+ CP is validated, a role for CP-dependent Fe2+ sequestration during infection will need to be investigated.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The ability of S100 proteins to bind transition metals at sites separate from their Ca2+ binding sites highlights the complexities of their biochemical actions and the everchanging environments within and outside cells. Structural analyses have identified specific conformational changes induced by Ca2+ and transition metals. However, information is urgently needed to understand if and how transition metals modulate S100 protein interactions with their targets. Questions regarding oligomerization state and whether transition metal binding is needed for signaling to occur also need to be addressed. Substantial evidence for S100 proteins in human disease suggests there is significant potential in pursuing S100 proteins as therapeutic targets and motivates ongoing efforts in multiple laboratories to develop S100 protein-specific inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by operating grant (R01 AI101171 to Eric P. Skaar and Walter J. Chazin), and institutional training grant (T32 ES007028 support for Benjamin A. Gilston) from the US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance and ethics The author(s) declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnesano F, Banci L, Bertini I, Fantoni A, Tenori L, Viezzoli MS. Structural interplay between calcium(II) and copper(II) binding to S100A13 protein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:6341–6344. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudier J, Glasser N, Gerard D. Ions binding to s100 proteins. I. Calcium- and zinc-binding properties of bovine brain s100 alpha alpha, s100a (alpha beta), and s100b (beta beta) protein: Zn2+ regulates Ca2+ binding on s100b protein. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8192–8203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudier J, Glasser N, Haglid K, Gerard D. Purification, characterization and ion binding properties of human brain S100b protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;790:164–173. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudier J, Holtzscherer C, Gerard D. Zinc-dependent affinity chromatography of the S100b protein on phenyl-Sepharose. A rapid purification method. FEBS Lett. 1982;148:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Bunick CG, Chazin WJ. Target selectivity in EF-hand calcium binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1742:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen DE, Nyborg J, Kjeldgaard M. Zinc-binding site of an S100 protein revealed. Two crystal structures of Ca2+-bound human psoriasin (S100A7) in the Zn2+-loaded and Zn2+-free states. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1695–1704. doi: 10.1021/bi982483d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy MB, Nolan EM. Manganese and microbial pathogenesis: sequestration by the Mammalian immune system and utilization by microorganisms. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:641–651. doi: 10.1021/cb500792b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy MB, Hayden JA, Nolan EM. Calcium ion gradients modulate the zinc affinity and antibacterial activity of human calprotectin. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18089–18100. doi: 10.1021/ja307974e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy MB, Nakashige TG, Gaillard A, Nolan EM. Contributions of the S100A9 C-terminal tail to high-affinity Mn(II) chelation by the host-defense protein human calprotectin. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17804–17817. doi: 10.1021/ja407147d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunick CG, Nelson MR, Mangahas S, Hunter MJ, Sheehan JH, Mizoue LS, Bunick GJ, Chazin WJ. Designing sequence to control protein function in an EF-hand protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5990–5998. doi: 10.1021/ja0397456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier MC, Pierce AD, Wilder PT, Alasady MJ, Hartman KG, Neau DB, Foley TL, Jadhav A, Maloney DJ, Simeonov A, Toth EA, Weber DJ. Covalent small molecule inhibitors of Ca2+-bound S100B. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6628–6640. doi: 10.1021/bi5005552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier TH, Wilder PT, Liriano MA, Varney KM, Pozharski E, MacKerell AD, Jr., Coop A, Toth EA, Weber DJ. Divalent metal ion complexes of S100B in the absence and presence of pentamidine. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier TH, Wilder PT, Liriano MA, Varney KM, Zhong S, Coop A, Pozharski E, MacKerell AD, Jr., Toth EA, Weber DJ. Small molecules bound to unique sites in the target protein binding cleft of calcium-bound S100B as characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray crystallography. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6202–6212. doi: 10.1021/bi9005754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazin WJ. The impact of X-ray crystallography and NMR on intracellular calcium signal transduction by EF-hand proteins: crossing the threshold from structure to biology and medicine. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:pe27. doi: 10.1126/stke.3882007pe27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HL, Jhingran A, Sun Y, Vareechon C, de Jesus Carrion S, Skaar EP, Chazin WJ, Calera JA, Hohl TM, Pearlman E. Zinc and manganese chelation by neutrophil S100A8/A9 (Calprotectin) limits extracellular Aspergillus fumigatus hyphal growth and corneal infection. J Immunol. 2016;196:336–344. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin BD, Seeley EH, Raab A, Feldmann J, Miller MR, Torres VJ, Anderson KL, Dattilo BM, Dunman PM, Gerads R, Caprioli RM, Nacken W, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Metal chelation and inhibition of bacterial growth in tissue abscesses. Science. 2008;319:962–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1152449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damo SM, Kehl-Fie TE, Sugitani N, Holt ME, Rathi S, Murphy WJ, Zhang Y, Betz C, Hench L, Fritz G, Skaar EP, Chazin WJ. Molecular basis for manganese sequestration by calprotectin and roles in the innate immune response to invading bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3841–3846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220341110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC, Schleicher CH, Santome JA. Primary structure and binding properties of calgranulin C, a novel S100-like calcium-binding protein from pig granulocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28929–28936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:540–551. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R, Cannon BR, Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Hsu K, Weber DJ, Geczy CL. Functions of S100 proteins. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:24–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G, Heizmann CW, Kroneck PM. Probing the structure of the human Ca2+- and Zn2+-binding protein S100A3: spectroscopic investigations of its transition metal ion complexes, and three-dimensional structural model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1448:264–276. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G, Mittl PR, Vasak M, Grutter MG, Heizmann CW. The crystal structure of metal-free human EF-hand protein S100A3 at 1.7-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33092–33098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günter F, Heizmann CW. Handbook of Metallproteins. 2006. 3D Structures of the Calcium and Zinc Binding S100 Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy JA, Radin JN, Loh JT, Piazuelo MB, Kehl-Fie TE, Delgado AG, Ilca FT, Peek RM, Cover TL, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP, Scott Algood HM. The host protein calprotectin modulates the Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system via zinc sequestration. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004450. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon DM, Brophy MB, Bowman SE, Stich TA, Drennan CL, Britt RD, Nolan EM. Manganese binding properties of human calprotectin under conditions of high and low calcium: X-ray crystallographic and advanced electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopic analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3004–3016. doi: 10.1021/ja512204s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribenko AV, Makhatadze GI. Oligomerization and diva-lent ion binding properties of the S100P protein: a Ca2+/Mg2+-switch model. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:679–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase-Kohn C, Wolf S, Lenk J, Pietzsch J. Copper-mediated cross-linking of S100A4, but not of S100A2, results in proinflammatory effects in melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413:494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley KP, Delgado AG, Piazuelo MB, Mortensen BL, Correa P, Damo SM, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP, Gaddy JA. The human antimicrobial protein calgranulin C participates in control of Helicobacter pylori growth and regulation of virulence. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2944–2956. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00544-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA, Brophy MB, Cunden LS, Nolan EM. High-affinity manganese coordination by human calprotectin is calcium-dependent and requires the histidine-rich site formed at the dimer interface. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:775–787. doi: 10.1021/ja3096416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann CW, Cox JA. New perspectives on S100 proteins: a multi-functional Ca2+-, Zn2+- and Cu2+-binding protein family. Biometals. 1998;11:383–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1009212521172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann CW, Fritz G, Schäfer BW. S100 proteins: structure, functions and pathology. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1356–1368. doi: 10.2741/A846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood MI, Mortensen BL, Moore JL, Zhang Y, Kehl-Fie TE, Sugitani N, Chazin WJ, Caprioli RM, Skaar EP. Identification of an Acinetobacter baumannii zinc acquisition system that facilitates resistance to calprotectin-mediated zinc sequestration. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003068. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura M. Calcium binding and conformational response in EF-hand proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl-Fie TE, Chitayat S, Hood MI, Damo S, Restrepo N, Garcia C, Munro KA, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Nutrient metal sequestration by calprotectin inhibits bacterial superoxide defense, enhancing neutrophil killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl-Fie TE, Zhang Y, Moore JL, Farrand AJ, Hood MI, Rathi S, Chazin WJ, Caprioli RM, Skaar EP. MntABC and MntH contribute to systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection by competing with calprotectin for nutrient manganese. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3395–3405. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00420-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizawa K, Jinbo Y, Inoue T, Takahara H, Unno M, Heizmann CW, Izumi Y. Human S100A3 tetramerization propagates Ca2+/Zn2+ binding states. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013a;1833:1712–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizawa K, Unno M, Takahara H, Heizmann CW. Purification and characterization of the human cysteine-rich S100A3 protein and its pseudo citrullinated forms expressed in insect cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2013b;963:73–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-230-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Bhattacharya S, Kehl T, Gimona M, Vasak M, Chazin W, Heizmann CW, Kroneck PM, Fritz G. Implications on zinc binding to S100A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordowska J, Stafford WF, Wang CL. Ca2+ and Zn2+ bind to different sites and induce different conformational changes in human calcyclin. Euro J Biochem. 1998;253:57–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korndorfer IP, Brueckner F, Skerra A. The crystal structure of the human (S100A8/S100A9)2 heterotetramer, calprotectin, illustrates how conformational changes of interacting alpha-helices can determine specific association of two EF-hand proteins. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon R, Murray JI, Cragg G, Farnell B, West NR, Pace TC, Watson PH, Bohne C, Boulanger MJ, Hof F. Identification and characterization of binding sites on S100A7, a participant in cancer and inflammation pathways. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10591–10600. doi: 10.1021/bi901330g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Yang Q, Yan Z, Markowitz J, Wilder PT, Carrier F, Weber DJ. Inhibiting S100B restores p53 levels in primary malignant melanoma cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34071–34077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linse S, Chazin WJ. Quantitative measurements of the cooperativity in an EF-hand protein with sequential calcium binding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1038–1044. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malashkevich VN, Dulyaninova NG, Ramagopal UA, Liriano MA, Varney KM, Knight D, Brenowitz M, Weber DJ, Almo SC, Bresnick AR. Phenothiazines inhibit S100A4 function by inducing protein oligomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8605–8610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913660107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maler L, Sastry M, Chazin WJ. A structural basis for S100 protein specificity derived from comparative analysis of apo and Ca2+-calcyclin. J mol biol. 2002;317:279–290. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BW. A soluble protein characteristic of the nervous system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;19:739–744. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Antson AA, Dodson EJ, Burrell HJ, Grist SJ, Lloyd RM, Maitland NJ, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Lukanidin E, Bronstein IB. The structure of S100A12 in a hexameric form and its proposed role in receptor signalling. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:407–413. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901021278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Antson AA, Grist SJ, Maitland NJ, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Lukanidin E, Bronstein IB. Structure of the human S100A12-copper complex: implications for host-parasite de-fence. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:859–867. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903004700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Blagova EV, Wilkinson AJ, Wilson KS, Bronstein IB. The crystal structures of human S100A12 in apo form and in complex with zinc: new insights into S100A12 oligomerisation. J Mol Biol. 2009a;391:536–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Burkitt W, Wittkowski H, He W, Ianoul A, Novitskaya V, Xie J, Polyakova O, Lednev IK, Shekhtman A, Derrick PJ, Bjoerk P, Foell D, Bronstein IB. Both Ca2+ and Zn2+ are essential for S100A12 protein oligomerization and function. BMC Biochem. 2009b;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Burkitt W, Wittkowski H, He W, Ianoul A, Novitskaya V, Xie J, Polyakova O, Lednev IK, Shekhtman A, Derrick PJ, Bjoerk P, Foell D, Bronstein IB. Both Ca2+ and Zn2+ are essential for s100a12 protein oligomerization and function. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz OV, Wilson KS, Bronstein IB. The role of zinc in the S100 proteins: insights from the X-ray structures. Amino Acids. 2011;41:761–772. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JI, Tonkin ML, Whiting AL, Peng F, Farnell B, Cullen JT, Hof F, Boulanger MJ. Structural characterization of S100A15 reveals a novel zinc coordination site among S100 proteins and altered surface chemistry with functional implications for receptor binding. BMC Struct Biol. 2012;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashige TG, Zhang B, Krebs C, Nolan EM. Human calprotectin is an iron-sequestering host-defense protein. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MR, Chazin WJ. Structures of EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins: diversity in the organization, packing and response to Ca2+ binding. Biometals. 1998;11:297–318. doi: 10.1023/a:1009253808876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MR, Thulin E, Fagan PA, Forsen S, Chazin WJ. The EF-hand domain: a globally cooperative structural unit. Protein Sci. 2002;11:198–205. doi: 10.1110/ps.33302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Lee IS, Shiraishi N, Ishikawa T, Ohta Y, Nishikimi M. Identification of S100b protein as copper-binding protein and its suppression of copper-induced cell damage. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23037–23041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostendorp T, Diez J, Heizmann CW, Fritz G. The crystal structures of human S100B in the zinc- and calcium-loaded state at three pH values reveal zinc ligand swapping. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostendorp T, Leclerc E, Galichet A, Koch M, Demling N, Weigle B, Heizmann CW, Kroneck PM, Fritz G. Structural and functional insights into RAGE activation by multimeric S100B. EMBO J. 2007;26:3868–3878. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J, Kim BH, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BC, Carlstrom G, Okazaki K, Hidaka H, Chazin WJ. 1H NMR assignments of apo calcyclin and comparative structural analysis with calbindin D9k and S100 beta. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2162–2174. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BC, Smith J, Akke M, Macke TJ, Okazaki K, Hidaka H, Case DA, Chazin WJ. The structure of calcyclin reveals a novel homodimeric fold for S100 Ca2+-binding proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:790–796. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustandi RR, Baldisseri DM, Drohat AC, Weber DJ. The Ca2+-dependent interaction of s100b(beta beta) with a peptide derived from p53. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1951–1960. doi: 10.1021/bi972701n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer BW, Heizmann CW. The S100 family of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins: functions and pathology. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)80167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer BW, Fritschy JM, Murmann P, Troxler H, Durussel I, Heizmann CW, Cox JA. Brain S100A5 is a novel calcium-, zinc-, and copper ion-binding protein of the EF-hand superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30623–30630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub MC, Heizmann CW. Calcium, troponin, calmodulin, S100 proteins: from myocardial basics to new therapeutic strategies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel A, Sigel H. Manganese and its role in biological processes. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraja V, Kumar TK, Rajalingam D, Graziani I, Prudovsky I, Yu C. Copper binding affinity of S100A13, a key component of the FGF-1 nonclassical copper-dependent release complex. Biophys J. 2006;91:1832–1843. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striz I, Trebichavsky I. Calprotectin-a pleiotropic molecule in acute and chronic inflammation. Physiol Res. 2004;53:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturchler E, Cox JA, Durussel I, Weibel M, Heizmann CW. S100A16, a novel calcium-binding protein of the EF-hand superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38905–38917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno M, Kawasaki T, Takahara H, Heizmann CW, Kizawa K. Refined crystal structures of human Ca2+/Zn2+-binding S100A3 protein characterized by two disulfide bridges. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:477–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dieck J, Teufel DP, Jaulent AM, Fernandez-Fernandez MR, Rutherford TJ, Wyslouch-Cieszynska A, Fersht AR. Posttranslational modifications affect the interaction of S100 proteins with tumor suppressor p53. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl T, Leukert N, Barczyk K, Strupat K, Roth J. Biophysical characterization of S100A8 and S100A9 in the absence and presence of bivalent cations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1298–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorum H, Madsen P, Rasmussen HH, Etzerodt M, Svendsen I, Celis JE, Honoré B. Expression and divalent cation binding properties of the novel chemotactic inflammatory protein psoriasin. Electrophoresis. 1996;17:1787–1796. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150171118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder PT, Baldisseri DM, Udan R, Vallely KM, Weber DJ. Location of the Zn2+-binding site on S100B as determined by NMR spectroscopy and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13410–13421. doi: 10.1021/bi035334q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder PT, Varney KM, Weiss MB, Gitti RK, Weber DJ. Solution structure of zinc- and calcium-bound rat S100B as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5690–5702. doi: 10.1021/bi0475830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf R, Howard OM, Dong HF, Voscopoulos C, Boeshans K, Winston J, Divi R, Gunsior M, Goldsmith P, Ahvazi B, Chavakis T, Oppenheim JJ, Yuspa SH. Chemotactic activity of S100A7 (Psoriasin) is mediated by the receptor for advanced glycation end products and potentiates inflammation with highly homologous but functionally distinct S100A15. J Immunol. 2008;181:1499–1506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackular JP, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: S100 proteins at the host-pathogen interface. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18991–18998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.645085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]