Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to assess the knowledge of definition of cancer survivors among Japanese oncology nurses and their roles in long-term cancer survivorship care.

Methods:

A structured self-administered and self-report questionnaire created by the study investigators was given to members of the Japanese Society of Cancer Nursing. The subjects were 81 female oncology nurses.

Results:

Forty-nine nurses had 11 or more years of nursing experience, while 27 nurses had cancer-related nursing certifications such as, certification in oncology nursing specialist. This study population had rather rich experience in oncology nursing. Sixty-two nurses defined a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis, while the nurses’ recognition of long-term survivorship care was poor, compared with nursing care at the time of diagnosis, during treatment, and end of life.

Conclusions:

The nurses were aware of the needs to recognize and address issues faced by long-term cancer survivors and for nursing study, but very few put the effective patient education and interventions into practice. It is because oncology nurses have few chances to see cancer survivors who go out of the hands of healthcare professionals. In increasing the number of long-term survivors, long-term survivorship care is needed in addition to incorporating such education into undergraduate and graduate programs. Further study on the knowledge of long-term cancer survivorship care and nursing practices are required.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship, long-term survival, oncology nurses’ recognition

Introduction

In Japan, cancer has been the most common cause of death since 1981. Recently 600,000 people are newly diagnosed with cancer each year, while 300,000 people die. The cancer survival rates over 5 years are more than 50% for stomach, 60% for colon, and 80% for breast.[1] The phrase “cancer survivor” has been commonly used since the Cancer Control Act was implemented in 2007.[2,3] The importance of coordination in healthcare and welfare that provides support for patients living with cancer is becoming more apparent, because of increasing the number of long-term survivors.

The cancer survivorship was defined by Mullan in 1985 as “survival begins at the point of diagnosis” based on his experience of fighting cancer.[4] With this concept, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) created the widely accepted definition of survivorship and defines someone as a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life.[5] Also, as to who should receive survivorship care, Hewitt et al.[6] stated that there are individuals who are in the period of “cancer-free survival” following their treatment. It is recognized that people are living longer following a cancer diagnosis, and it is no longer sufficient to focus all of our attention on the diagnosis and treatment phases of the disease. Focus must be placed on the potential long-term effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment, the need for appropriate assessment, surveillance for cancer, prevention of recurrence, and attention to the needs of people living beyond the primary treatment phase of their disease.[6] There are broad categories of needs such as smoking, exercise, weights, diet, sexual issues, and others, because patients will have their own needs depending on the diagnosis.[6,7,8] One area of concern is lack of knowledge on the part of patients and care providers about the appropriate type, frequency, and duration of surveillance for cancer recurrence, screening for health issues associated with the initial cancer and treatment.[9,10,11,12] To date, however, little research has focused on the oncology nurses’ perceived role, behaviors and ability to educate patients on strategies for care beyond the treatment phase.[13] Unfortunately, there are no effective means of measuring the level of cancer survivorship care.

Findley and Feverstein[14] pointed out that care programs designed specifically for long-term cancer survivors had not been developed in Asian countries, including Japan. In the future, research studies and clinical practice in long-term cancer survivorship care will become more important in Asian countries, which pose a new challenge for cancer care in Japan. Therefore, we conducted a survey to understand and compare opinions and recognitions of cancer survivorship care and support among oncology nurses who were members of the Japanese Cancer Nursing Society (JSCN) and the Metro Minnesota Oncology Nursing Society (MMONS).[15,16]

The purpose of our study in this literature is to assess the knowledge of definition of cancer survivors among Japanese oncology nurses and their roles in long-term cancer survivorship care.

Materials and Methods

Design

A descriptive and cross-sectional design was used in this study. We collected data using self-administered and self-report questionnaires.

Sample and survey

The subjects were deemed eligible if they were members of JSCN and practicing cancer care in hospitals or clinics close to the study investigators in Northern, Central, and Western Japan. Each investigator was responsible for calling 10-13 nurses to receive the questionnaire. A letter and questionnaire with a stamped reply envelope were sent by post to 100 nurses, with 81 of 94 responses (86.2%) validated for use in the study. Thirteen of the responses were excluded because not all questions had been answered. The study period was from July 2009 to February 2010.

Procedure

A collaborative study group consisting of members of JSCN and MNONS in the United States discussed potential questions and created a unique questionnaire. At first, one nurse from MMONS and three nurses from JSCN met in Japan to discuss and develop the questionnaire. For several months thereafter, feedback from each team was used to clarify the questionnaire. Then, the JSCN team conducted a trial of the questionnaires with ten graduate oncology students. Although a content validity index of the questionnaire was not used on the trial, there was not any change with the content of the questionnaire excepting adjustments in wording.

Measurement

The survey consisted of seven demographic questions about gender, age, years of experience, oncology nursing experience, type of practice setting, final education, and certification in oncology nursing. The questions about recognition were configured in the definition of cancer survivors, learning needs of cancer survivorship care, and the role of long-term cancer survivorship care. In addition to these, we enquired about the impacting issues and the components of important care for two long-term survivors.

Definition of cancer survivor

Respondents were asked to select from one of the following options about when people become a cancer survivor: From the time of diagnosis, at completion of treatment, after reaching 5 years post-treatment, and bereaving families after patient's death.

Views on cancer survivorship care and learning needs

To investigate views on cancer survivorship care, nursing care was classified into 16 categories based on previous studies[6,7,8,9,10,11] and the core curriculum for cancer nursing.[17] The multiple-choice questionnaire was given to select 4 out of 16 components of nursing care that would be required at four specific phases from diagnosis to completion of initial treatment, after completion of initial treatment or on maintenance treatment, time during which a risk of recurrence is gradually reduced, and end of life. For learning needs, respondents were asked to rate the degree of learning needs regarding 16 types of nursing care on a Likert scale in four levels from “very high” to “none.”

Roles required in long-term cancer survivorship care

To gain insight into views of practicing nurses on roles required in supporting long-term cancer survivors, they were asked to respond on a Likert scale in four levels from “strongly agree” to “disagree” about the following understanding issues faced by long-term cancer survivors: recognizing potential issues, delivering effective patient education or nursing intervention, and a need for nursing study.

Case study of long-term cancer survivorship care

To understand the paradigm of long-term survivorship care, two patient cases were given. Respondents were asked to freely write three potential issues that could strongly impact long-term survival, and three components of care that were important for long-term survival. The two cases were of a young woman with Hodgkin's disease with a prognosis of long-term survival after treatment, and an elderly man with advanced lung cancer after completion of chemotherapy [Table 1].

Table 1.

Case study

| Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|

| A 24-year-old woman with Stage IV Hodgkin's disease is living in a suburb (2 h by train from city center) with her husband who frequently travels abroad for business. Her parents live in the neighborhood. She is planning to start a family within 1 or 2 years. She has been attending college to get a business degree and works part-time. She was referred to a Cancer Specialist Hospital for treatment, and has completed 6 months of chemotherapy followed by 2 months of radiation therapy. There was no treatment discontinuation or complication requiring suspension of treatment while she was on treatment. She lost her hair, had skin redness on her chest wall, and complains of fatigue. She is due to return to the cancer specialist hospital where she had her treatment for regular check-ups | A 60 year-old-man with stage IV-small cell lung cancer is living in a large city with his wife and their second son. His wife looks after a child (2 years old) of their first son. His cancer was detected at a regular health check in his workplace (press operator due to retire next year). He finished 3 months of chemotherapy at a Cancer Specialist Hospital. He experienced severe side effects that could have interfered with the treatment; he had been obese but lost 20 kg due to severe diarrhea, looked haggard and pale, had difficulty in hearing and breathing, and felt physically fragile. His wife was worried about his diet, and feeling bad about a fact that both of them smoked, which might have caused his cancer. Although he was self-contained and did not ask much about his treatment or anything thereafter, now at 6 months after treatment, complete remission has been achieved. He looks rejuvenated and better, and asks when he can return to work |

Data analysis

For quantitative data, the cross tabulation, Chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test in SPSS version 17 (IBM SPSS Advanced Statistics) were performed to determine the relationship between oncology nursing experience and learning needs. For qualitative data of case study questions, similar answers per component of care were aggregated to identify subcategories, and then similar subcategories were condensed to make categories. This was performed in order to refine the qualitative analysis examined between researchers.

Ethical considerations

This study plan was submitted to and approved by the ethical review board of the JSCN. The letter to subjects explained the purpose and method of this survey, and that participants were completely voluntary and were considered to have agreed to participation by returning the completed anonymous questionnaire.

Results

Demographic data

The demography of the subjects is shown in Table 2. All subjects were female, and 42 (51.9%) were aged 36-45. The 49 nurses (60.5%) were majority of the subjects, had 11 or more years of experience in oncology nursing. For the type of practice setting, 44 nurses (54.3%) were working in general hospitals and 34 (42%) were in cancer specialist hospitals. For final education, 40 (49.4%) graduated from a vocational school with a 3-year program, and 27 (33.3%) from graduate school. Also, 10 (12.3%) were oncology certified nurse specialists and 17 (21%) oncology certified nurses. Among the nurses who had 11 or more years of experience in oncology nursing, eight were certified nurse specialists, and 14 were certified nurses.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (n = 81)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 0(0) |

| Female | 81(100) |

| Age (years) | |

| 20-25 | 1(1.2) |

| 26-35 | 23(28.4) |

| 36-45 | 42(51.9) |

| 46-55 | 11(13.6) |

| >56 | 4(4.9) |

| Years of nursing experience | |

| <5 | 3(3.7) |

| 5-10 | 16(19.8) |

| 11-20 | 32(39.5) |

| >21 | 30(37.0) |

| Years of oncology nursing experience | |

| <3 | 2(2.5) |

| 3-4 | 8(9.9) |

| 5-10 | 21(25.9) |

| >11 | 49(60.5) |

| No answer | 1(1.2) |

| Type of practice setting | |

| Cancer centers | 34(42.0) |

| General hospitals | 44(54.3) |

| Others | 3(3.7) |

| Final education | |

| Graduate school | 27(33.3) |

| University | 8(9.9) |

| Junior college | 6(7.4) |

| Certification in oncology nursing | |

| Certified Nurse Specialists (CNS) | 10(12.3) |

| (11 or more years experience CNSs 8) | |

| Certified Nurse (CN) | 17(21.0) |

| (11 or more years experience CNs 14) |

Definition of cancer survivor

With regards to the time when patients become cancer survivors, 62 (76.5%) oncology nurses answered as “from the time of diagnosis,” 13 (16.1%) selected “at completion of treatment,” and 6 (7.4%) opted others.

Recognition of cancer survivorship care and learning needs

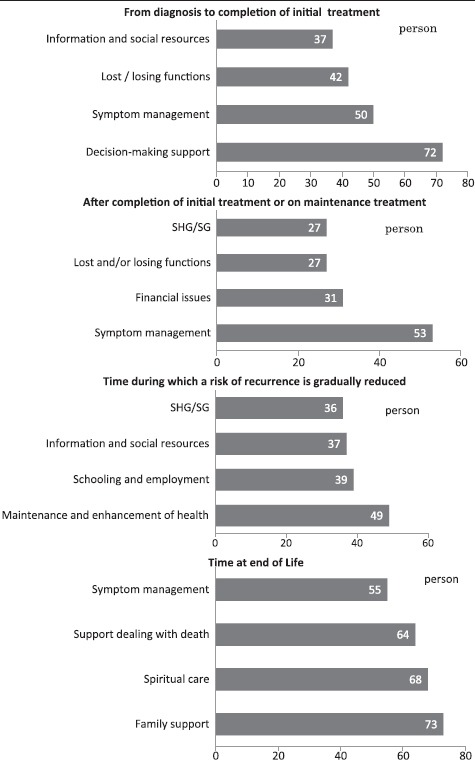

We divided a patient journey into four phases [Figure 1]. Long-term survivorship care falls into the “time during which a risk of recurrence is gradually reduced.” The components of care in this phase were related to maintenance and enhancement of health, assistance with schooling and employment, information and social resources, self-help group and help group.

Figure 1.

Four important cares in 4 phases of patient jorney (n = 81) (SHG/SG; self-help group/support group).

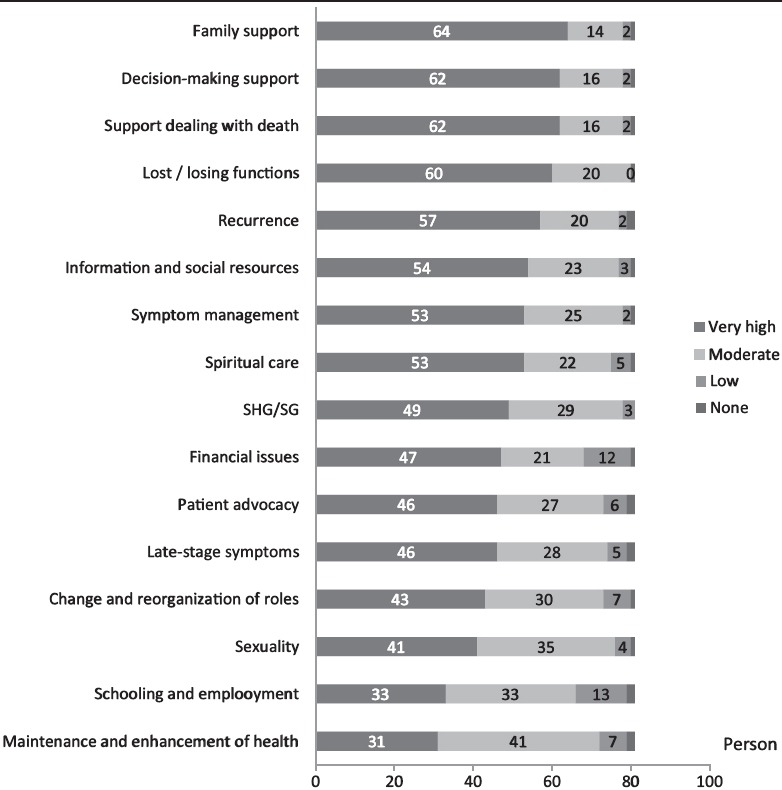

In the learning needs of 16 components of nursing care [Figure 2], the top four components of nursing care with “very high” learning needs were related to “family support,” “decision-making support,” “support dealing with death,” and “adapting to lost and/or losing functions”. The lowest four components nursing care were “related to promotion of health,” “schooling and employment,” “sexuality,” and “change and reorganization of roles”. For the relationship between oncology nursing experience and learning needs, “the learning needs regarding assistance with schooling and employment,” “change and reorganization of roles,” and “sexuality” are higher in nurses with 11 or more years of experience in oncology nursing than in nurses with <11 years of experience [Table 3].

Figure 2.

Learning needs regarding 16 types of nursing care (n = 81) (SHG/SG; self-help group/support group)

Table 3.

Learning needs and nurses’ experience in oncology nursing (n = 81)

| Learning needs | Years of oncology nursing experience | Need exists | No needs | Chi-square text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schooling/employment | ≤10 years | 21 | 11 | χ2=10.52 P=0.001* |

| ≥11 years | 45 | 3 | ||

| Change/reorganization of roles | ≤10 years | 26 | 6 | χ2=6.68 P=0.014** |

| ≥11 years | 47 | 1 | ||

| Sexuality | ≤10 years | 28 | 4 | χ2=6.32 P=0.022** |

| ≥11 years | 48 | 0 |

*Fisher's exact test, P < 0.001, **Fisher's exact test, P < 0.05

Views on roles required in long-term survivorship care

Among four roles with strongly agree, 81.5% of nurses responded “being aware of issues faced by long-term survivors,” 64.4% did “helping long-term survivors recognize potential issues in long-term survival,” 48.1% did “nursing study should be conducted on potential issues faced by long-term survivors,” and 23.5% did “effective approaches of educating patients or nursing interventions about long-term survival” [Table 4].

Table 4.

Roles required in long-term cancer survivorship care (n = 81)

| Views on nurse's roles | Strongly agree, n (%) | Agree, n (%) | Slightly agree, n (%) | Do not agree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being aware of issues faced by long-term survivors | 66 (81.5) | 13 (16.0) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Helping long-term survivors recognize potential issues in long-term survival | 52 (64.4) | 25 (31.6) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nursing study should be conducted on potential issues faced by long-term survivors | 39 (48.1) | 35 (43.2) | 7 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Effective approaches of educating patients or nursing interventions about long-term survival | 19 (23.5) | 38 (47.9) | 16 (19.8) | 8 (9.9) |

Case study of long-term cancer survivorship care

Regarding the impacting issues and the components of important care in long-term survival for case 1, 240 issues were drawn from multiple responses and classified into 14 categories, while 228 components were drawn and classified into 14 categories [Table 5]. For case 2, 218 issues were drawn and classified into 15 categories, while 243 components were drawn and classified into 13 categories [Table 6].

Table 5.

Issues that can seriously impact long-term survival and components of care that are important for long-term survival for Case 1

| Issues that can seriously impact long-term survival | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptom management | 38 (15.8) |

| Childbearing | 37 (15.4) |

| Support for families of patients | 34 (14.2) |

| Risk of recurrence and progression of disease status | 34 (14.2) |

| Risks related to treatment | 27 (11.3) |

| Issues with social rehabilitation | 13 (5.4) |

| Change of role in society/life plan | 12 (5.0) |

| Feeling of burden about hospital visits | 11 (4.6) |

| Support provided by others except family | 8 (3.3) |

| Financial issues | 7 (2.9) |

| Sexuality | 7 (2.9) |

| Understanding the disease | 5 (2.1) |

| Others (being young at 24 years of age, decision-making of distress, coexistence with the disease, keeping the identity) | 4 (1.7) |

| Spiritual issues | 3 (1.3) |

| Total | 240 (100) |

| Components of care that are important for long-term survival | |

| Help with symptom management/self-care | 51 (22.4) |

| Support for families | 31 (13.6) |

| Psychological support for patients | 26 (11.4) |

| Help with strengthening social support | 24 (10.5) |

| Help with further understanding of disease and treatment | 19 (8.3) |

| Help with sexuality | 14 (6.1) |

| Help with childbearing/family plan | 12 (5.3) |

| Help with continuation of regular hospital visits | 11 (4.8) |

| Help with change of roles/life plan | 9 (4.0) |

| Assistance with social rehabilitation | 9 (4.0) |

| Help with decision-making | 7 (3.1) |

| Assistance with financial issues | 6 (2.6) |

| Spiritual care | 5 (2.2) |

| Help with maintenance and enhancement of health | 4 (1.6) |

| Total | 228 (100) |

Table 6.

Issues that can seriously impact long-term survival and components of care that are important for long-term survival for Case 2

| Issues that can seriously impact long-term survival | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Risk of recurrence and progression of disease status | 38 (17.4) |

| Symptom management | 31 (14.2) |

| Lifestyle and health management | 29 (13.3) |

| Issues with social rehabilitation | 19 (8.7) |

| Psychological status of patients | 14 (6.4) |

| Change of role in society | 13 (6.0) |

| Support for families of patients | 12 (5.5) |

| Anxiety about recurrence | 12 (5.5) |

| Loss of physical strength/functions | 10 (4.6) |

| Spiritual issues | 10 (4.6) |

| Psychological and physical influence of severe side effects experienced | 8 (3.7) |

| Anxiety of/support for families | 7 (3.2) |

| Understanding the disease | 6 (2.8) |

| Financial issues | 6 (2.8) |

| Decision-making issues | 3 (1.4) |

| Total | 218 (100) |

| Components of care that are important for long-term survival | |

| Help with maintenance and enhancement of health | 47 (19.3) |

| Psychological support | 38 (15.6) |

| Support for families | 32 (13.2) |

| Help with symptom management/self-care | 32 (13.2) |

| Assistance with social rehabilitation | 19 (7.8) |

| Help with strengthening social support | 17 (7.0) |

| Assistance with possible recurrence | 15 (6.2) |

| Help with continuation of regular hospital visits | 11 (4.5) |

| Assistance with financial issues | 10 (4.1) |

| Spiritual care | 8 (3.3) |

| Assistance with having positive attitude toward life | 6 (2.5) |

| Help with decision-making | 5 (2.1) |

| Others (role, dealing with long-term treatment, support for self-advocacy) | 3 (1.2) |

| Total | 243 (100) |

Discussion

Subjects’ background

In this survey, the majority of the respondents were oncology nurses in practice who have expert knowledge of oncology nursing. Many nurses had 11 or more years of experience in clinical oncology nursing and were working in general hospitals or cancer specialist hospitals. Thus, the study population had rich experience of oncology nursing. Therefore, it might be difficult to say that the study results reflect the actual situation of oncology nurses in practice in Japan [Table 2]. We need a large sample size for further study.

Recognitions of oncology nurses in practice

For the definition of cancer survivor, the great majority said that people become a cancer survivor “from the time of diagnosis.” It shows that the oncology nurses had views in line with NCCS's definition.[5] Lester et al.[12] described that 35% of nurses saying cancer survivors at the time of diagnosis, with 40% of nurses saying more than 5 years in living.

For the components of important care at the four phases of patient journey, the top answers over 50 responses were “decision-making support” for the time from diagnosis to completion of initial treatment, “symptom management” for the time after completion of initial treatment or on maintenance treatment, and four components such as “family support” for the time at end of life. While there was no answer over 50 responses for the time during which a risk of recurrence is gradually reduced [Figure 1]. It suggests that oncology nurses in practice are more concerned with care at the times of diagnosis, during treatment, and end of life compared to long-term survivorship care.[18]

For learning needs about cancer survivors in general, the nurses felt their learning needs of nursing care were high in “family support,” “decision-making support,” “support dealing with death,” and “adapting to lost and/or losing functions,” while they felt less needs for learning about “support for maintenance and enhancement of health” and “assistance with schooling and employment” [Figure 2]. This suggests that the learning needs for long-term survivorship care were considered low. However, the learning needs regarding “assistance with schooling and employment,” “change and reorganization of roles,” and “sexuality” are higher in nurses with 11 or more years of experience in oncology nursing than in nurses with < 11 years of experience [Table 3]. Therefore, this may indicate that nurses become more aware of the importance of long-term survivorship care as they gain more clinical experience and knowledge in cancer nursing. And also it seems to be important that such nurses are educated in graduate school and certified nurse-training institutions in addition to gaining cancer-nursing experience. It is because some literature described that there is a need for continuation of education in clinical practice and the teaching of cancer survivorship care in undergraduate and graduate programs.[9,12,13]

For roles required in long-term cancer survivorship care, nurses were aware of the role of dealing with issues faced by long-term cancer survivors. And they were also concerned with potential issues and felt the need for nursing research on issues related to long-term survival. However, effective approaches for educating patients or nursing interventions have not been practiced in clinical. This may reflect the fact that many oncology nurses in Japan are involved in care at the time of diagnosis, during treatment, or end of life. This inevitably reduces the opportunities for them to provide long-term survivorship care.[18]

For a case study of long-term cancer survivorship care, case 1 was about a young woman who had received treatment for Hodgkin's disease, which has a high cure rate. The highest responses regarding the issues that could strongly impact long-term survival were “symptom management,” “childbearing,” and “family support,” while the components of important care were “help with symptom management/self-care” and “support for family and patients.” Case 2 was about an elderly male patient who had received treatment for lung cancer, which is recently improving with advanced treatment. The highest responses regarding the issues that could strongly impact long-term survival were “risk of recurrence and progression of disease status” “symptom management” and “lifestyle and health management,” while the components of important care were “help with maintenance and enhancement of health,” “support for family,” and “help with symptom management/self-care.” In considering of nurses’ recognition about the impacting issues and the components of important care in two cases, it seems that the nurses were aware of the different situations between two cases such as “childbearing” at case 1 and “lifestyle and health management” at case 2, but they mixed up the impacting issues and the components of important care. The nurses emphasized the support for patient and family and symptom management which are abstract expressions with no detailed descriptions, because of their limited experiences in long-term cancer survivorship care. Additionally, this shows the nurses’ common interest in psychosocial and physical aspects for the cancer care in Japan.[15]

In brief, it is said that recognition of long-term survival survivorship care was low among the nurses, because there was little chance of such care.[15] Therefore, further practice in long-term cancer survivorship and its study are required.

Future challenge for Japan

In Japan, we believe that increased opportunities for providing long-term cancer survivorship care will enable nurses to practice care that meets the needs of long-term cancer survivors. In order to understand the current status of long-term cancer survivors, we will need to conduct surveys and studies regarding various issues faced by long-term cancer survivors. We also must create guidelines and care models that will be suitable for Japanese patients, as Salz et al.[19] has indicated in the evaluation of cancer survivorship care that the guidelines are effective for care providers. In addition, we need to apply the education regarding long-term cancer survivorship care in Japan, as Ferrell and Winn[13] and Lester et al.[12] pointed out that such educational programs need to be provided by undergraduate and graduate programs.

Limitations

This study population had rich experience in oncology nursing. Therefore, the study results might not reflect the actual situation of oncology nurses in practice in Japan. The questionnaire was limited to measuring the knowledge of cancer survivorship care which covered 16 items, comparing 35 items in the study by Lester et al.[12] In order to make the nurses’ recognition of long-term cancer survivorship care more evidently, further study is required to have a large sample size including general oncology nurses and an improved questionnaire.

Conclusion

Majority of nurses defined a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis, while the nurses’ recognition of long-term survivorship care was poor, compared with nursing care at the time of diagnosis, during treatment, and end of life. The nurses were aware of the needs to recognize and address issues faced by long-term cancer survivors and for nursing study. On the other hand, there was a lack of nursing care including patient education and nursing interventions. It is because oncology nurses have few chances to see cancer survivors. Therefore, further study including nurses’ recognition of long-term cancer survivorship care in a large sample size and nursing practices are required. Also, the educational institutions are expected to incorporate such care into undergraduate and graduate programs.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by a grant of Japanese Society of Cancer Nursing.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Honkawa Data Tribune. Illustrated Records of 5-Year Survival Rates Based on Stages at Detection of Cancer. [Last accessed on 2008 May 15]. Available from: http://www2.ttcn.ne.jp/honkawa/2164.html .

- 2.Press Release. The 3rd Term Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; [Last accessed on 2008 May15]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2003/07/h0725-3.html . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Announcement. Cancer Control Act. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan) [Last accessed on 2008 Nov 20]. Available from: http://law.e-gov.go.jp/announce/H18HO098.html .

- 4.Mullan F. Seasons of survival: Reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507253130421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCCS. Silver Spring: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. c1995-2015. [Last accessed on 2008 Nov 20]. Available from: http://www.canceradvocacy.org .

- 6.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2270–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Hesse BW. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: Implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:179–89. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW, Mehta SR, Pine DA, Swenson KK. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Fam Med. 2007;39:477–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houldin A, Curtiss CP, Haylock PJ. Executive summary: The state of the science on nursing approaches to managing late and long-term sequelae of cancer and cancer treatment. Am J Nurs. 2006;106:54–9. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200603000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: Models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz PA. Survivorship: Adult cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36:721–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lester JL, Wessels AL, Jung Y. Oncology nurses’ knowledge of survivorship care planning: The need for education. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:E35–43. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.E35-E43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrell BR, Winn R. Medical and nursing education and training opportunities to improve survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5142–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Findley PA, Feverstein M. Global Considerations Handbook of Cancer Survivorship. Ch. 25. New York: Springer; 2006. Internatioal perspective; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura A. Towards Healthier Oncology Nursing: A Synergy of Scientific Minds. International Innovation. Research Media. EU. 2014;132:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onishi K, Johnson J, Anderson E, Miura A, Suzuki S, Swenson K. Oncology Nurse's Knowledge, Belief and Role in Long-term Cancer Survivorship in the US and Japan. 17th International Conference on Cancer Nursing. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itano JK, Taoka KN. In: Core Oncology Nursing Curriculum. Kojima M, Sato R, editors. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 2007. pp. 3–191. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asako Miura, KumikoTanaka Ykie Hosoda: Trends in Cancer Survivorship Care: A Literature Review of English Articles on Cancer Survivorship. Bulletin Fukushima Medical University School of Nursing. 2015;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]