Abstract

Purpose

To describe a novel strategy using linking social capital to provide healthcare access to irregular migrants with low literacy, low numeracy, and limited cultural assimilation in a European metropolitan area.

Organizing Construct

Public data show numerous shortcomings in meeting the healthcare needs of refugees and irregular migrants surging into Europe. Many irregular migrants living in European communities are unable to access information, care, or services due to lack of social capital. An overview of the problem and traditional charity strategies, including their barriers, are briefly described. A novel strategy using linking social capital to improve healthcare access of irregular migrants is explored and described. Information regarding the impact of this approach on the target population is provided. The discussion of nursing's role in employing linking social capital to care for the vulnerable is presented.

Conclusions

Immigration and refugee data show that issues related to migration will continue. The novel strategy presented can be implemented by nurses with limited financial and physical resources in small community settings frequented by irregular migrants to improve health care.

Clinical Relevance

The health and well‐being of irregular migrants has an impact on community health. Nurses must be aware of and consider implementing novel strategies to ensure that all community members’ healthcare needs, which are a basic human right, are addressed.

Keywords: Irregular migrants, social capital, community health, education, homelessness, health disparities, case study

Nursing is a profession concerned with the needs of vulnerable populations and the recognition of social, economic, and political determinates of health (Sigma Theta Tau International, 2005). Violence, conflict and extreme poverty are uprooting millions of people in the Middle East (Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan), Eastern Europe (Ukraine), Sub‐Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2015). As a result, record numbers of refugees and migrants are entering Europe (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2015). However, not all refugees and migrants use formal routes to obtain residency or asylum. Irregular migrants live in a precarious position of low social capital in the countries in which they reside.

Social capital is the relationship an individual has to a group that allows them to access resources, such as money, health care, information, or services (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). A sociological health principle describes this relationship well:

Social inequality affects health in direct and indirect ways. High inequality entails a larger proportion of the population living in relative poverty and governmental policies that neglect human investments (such as in education, health, and an array of services). Inequality also affects health indirectly through psychosocial factors related to our place in the social hierarchy. Social capital (trust and civic participation) declines with greater inequality. (Wermuth, 2003, p. 66)

Irregular migrants in Europe have limited access to basic human needs, such as education, health care, and housing, while being excluded from any civic involvement, which makes them exceptionally vulnerable. The close physical proximity between rich and poor enhances the harmful effects of inequality on a physical, mental, and social level (Massey, 1996). Together the lack of equality, social capital, and being excluded from civic involvement permit the reinforcement of hindrances to perpetuate isolation of the irregular migrant.

Background Factors

Clear data are available on refugees and migrants who take formal routes to gain asylum and residency. More than 625,000 asylum applications were submitted in the European Union in 2014 (Bitoulas, 2015). The makeup of asylum applicants in 2014 was 18–34 years of age (53.7%), 35–63 years of age (19.9%), 0–13 years of age (18.8%), 14–17 years of age (6.7%), 65 years of age and over (0.8%), and unknown (0.1%), with the majority being men (Bitoulas, 2015).

However, less information is available regarding irregular migration. Irregular migration is defined as “the movement of persons to a new place of residence or transit that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries,” and an irregular migrant is defined as “a person who, owing to irregular entry, breach of a condition of entry or the expiry of their legal basis for entering and residing, lacks legal status in a transit or host country” (European Migration Network, 2014, pp. 172–173). European Union member countries have less access to data on irregular migrants and generally base estimates on sanctions against employers for employing irregular migrants (European Migration Network, 2011). This type of data collection does not include irregular migrants who are present without employment or who are employed with employers who have not been sanctioned. The most recent data estimates on irregular migrants in Europe were collected by the Clandestino Project, commissioned by the European Union, which was terminated in 2009 (Clandestino, 2012). Estimates of irregular migrants, both working and nonworking, from data collected from 2007 to 2009, were between 1.9 million and 3.8 million for the 27 member states of the European Union (Eurostat, 2011).

Irregular migrants are at higher risk for health impairments because they do not have valid authorization to reside in the country where they live and therefore try to make a living in jobs that are typically dangerous or degrading while experiencing challenges in accessing health care, education, and housing (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Not all European Union states recognize the rights of irregular migrants to claim compensation for accidents in the workplace or provide a means to seek judicial redress when discriminatory or abusive practices occur in the workplace (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Access to health care for irregular migrants is variable between European Union states, and even in States that provide healthcare services there are obstacles of unawareness of entitlements and fear of information exchange between service providers and immigration enforcement authorities (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Education access for irregular migrant children is complicated by rules that require documentation for enrollment or to receive diplomas; as education levels increase, access becomes increasingly restrictive (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Housing is also problematic for irregular migrants who lack appropriate documentation to secure housing or lack sufficient financial resources to maintain a place of residence (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011).

International human rights should be applicable to every person, as a consequence of being human, regardless of immigration status (United Nations, 1948, 1966a, 1966b). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone is entitled to the rights and freedoms set forth in the Declaration, “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or other status” (United Nations, 1948, Article 2). Recommendations for European Union member states from sources such as the Universal Periodic Reviews and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control have focused on assurance of access to basic social services for irregular migrants, which includes health care (European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 2015; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011; United Nations, 2015).

Spain, where this public health project took place, had a unique process within the European Union for irregular migrants. Irregular entry was not considered a crime in Spain (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Spain was the only European country that allowed and fostered the registration of irregular migrants through a registration process called Padrón, which gave irregular migrants access to free medical care and public education on the same basis as Spaniards or regular migrants (Clandestino, 2009). Many South American immigrants, African, and Eastern Europeans entered the country as false tourists and used irregular migration as part of the process to gain residency or citizenship (Clandestino).

Irregular migrants in Spain could access other basic human needs, in addition to health care, via a broad charitable organization called Cáritas, which is the official charity group of the Catholic Church in Spain. Food, clothing, and other necessary supplies are distributed to those in need through offices located within Catholic churches; the physical address of a person or family corresponds to a specific church or dioceses where the person or family must go to receive services (Cáritas Española, 2009a, 2009b). The requirement to have a physical address, verified by a utility bill or government paper, to locate and receive services may be a barrier to irregular migrants who do not have access to stable housing, are not listed on utility bills, or do not receive government papers.

Due to an extended economic crisis, new legislation Real Decreto‐Ley 16/2012, 2012 was passed on April 20, 2012, that restricted access of irregular migrants, as well as other sections of the population, to the national healthcare system (Gobierno de España, 2012). In response, a nongovernmental organization (NGO), Yo Sí Sanidad Universal, was formed to denounce and work on the retraction of the law through civil disobedience by accompanying community members, including irregular migrants, who are excluded from healthcare services to seek assistance within the national healthcare system (Yo Si Sanidad Universal, 2015). The groups of accompaniment are most often organized and enacted with Spanish speakers (European Commission, 2012), which can be a barrier for irregular migrants who do not speak Spanish.

The right of the independent European states to enforce immigration law may have a negative indirect impact on the ability of migrants to access basic rights in the host country and may discourage irregular migrants from accessing support services from NGOs or charity organizations for fear of arrest (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). A common method of policing for irregular migrants within the European Union are routine identity checks that are often carried out on routine traffic stops, on public transportation, or in public spaces (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Identity checks carried out near schools, health centers, or religious buildings have an indirect effect of discouraging migrants from accessing charitable services and can be frightening, humiliating, or traumatic for the juxtaposition of seeking charitable services and being suspect at the same time (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011). Social circumstances shape the quality of one's life (Kawachi, 2001). Irregular migrants live with persistent fear and distrust because they reside in a society that does not recognize them (Skiba‐King, 2016). Enforcing immigration law at points of charitable service or resources for irregular migrants only deepens the fear and distrust while additionally building barriers to receiving fundamental basic rights.

Role of Social Capital in Irregular Migrant Health

Social capital has been linked to health outcomes in public health literature (Islam, Merlo, Kawachi, Lindstrom, & Gerdtham, 2006; Murayama, Fujiwara, & Kawachi, 2012). The concept of social capital has continued to evolve to include the nuances of “bonding,” “bridging,” and “linking” social capital. Bonding and bridging social capital are both horizontal in nature; bonding social capital involves trusting relationships between a network of people (e.g., family, friends) who view themselves as similar, while bridging social capital is based on mutual respect and support between group members who may not be alike in social identity or demographic (e.g., banks, police; Putnam, 2000). Linking social capital is a vertical strategy that links individuals in positions of high social capital with those individuals who lack social capital to open up and provide access to services or relationships that were previously inaccessible (Woolcock, 2001). Linking social capital is important in the health of poor communities where access to formal institutions, such as hospitals and clinics, must be based on trust and respect in order to improve access and health outcomes (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). Although linking social capital can be led by disadvantaged community members, trusting relationships are usually successfully formed when those with greater social capital reach out to those with less social capital (Gittell & Thompson, 2001; Noguera, 2001). Concisely, the burden resides with community members who have social capital to both recognize and create trusting relationships with those who lack social capital. Together, the action of high social capital community members initiating and interacting with vulnerable community members embodies the application of linking social capital to create change.

Meeting the needs of irregular migrants in the communities in which they live is an essential component of community health. Nurses, through the nurse–patient relationship, are well prepared to meet the needs of irregular migrants (Skiba‐King, 2016). Nurses are prepared academically to be change agents who can enter communities of irregular migrants and work as mediators to provide linking social capital to the unseen members of society through the intentional creation of trusting relationships. Individuals are only able to change their lifestyle habits and improve health if they are able to learn from honest and truthful individuals (Afzali, Shahhosseini, & Hamzeghardeshi, 2015). Linking social capital must be carefully constructed in order to create feelings of mutual respect and shared goals between group members and minimize the effects of the inherent power differential between those with high social capital and those with low social capital (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). Irregular migrants are outside the formal systems of society and lack social capital, which may impair them from seeking assistance through NGOs or charity organizations out of fear of deportment or lack of understanding due to low literacy, low numeracy, or insufficient language skills. Nurses can intercede on their behalf through the use of linking social capital.

Nurses as Change Agents

Nurses are viewed favorably in most societies (Shattell, 2004). Nursing's role in providing care to society's most vulnerable members through linking social capital has been clearly demonstrated since Lillian Wald and Mary Brewster began the Henry Street Settlement in New York's Lower East Side in 1893 and pioneered public health nursing (Yost, 1955). After a random, brief encounter with the living conditions of the immigrants inhabiting the Lower East Side of New York City, Wald became an activist to improve the health and well‐being of those who were on the fringe of society through public health initiatives and advocacy (Wald, 1915/2014). She noted during her first encounter with a family living in poverty, squalor, and social exclusion that “they [the immigrants] were not without ideals for the family life, and for society, of which they were so unloved and unlovely a part” (Wald, 1915/2014, p. 7). She linked the immigrant family's current condition with a lack of knowledge that could be rectified through education to help them avoid the natural consequences of their ignorance and promote health (Wald, 1915/2014).

In order to meet the needs of those at risk, Wald and Brewster moved into the Henry Street Settlement house in the Lower East Side to live near and directly attend to the issues of those living there (Wald, 1915/2014; Yost, 1955). Wald and Brewster navigated successfully to link social capital between privileged, educated, high‐status women and immigrants living in squalid conditions to build trust and construct mechanisms to meet community needs, which then improved health for both the immigrant community members and the larger community around them.

A Novel Approach Using Social Capital

An analogous public health nursing approach was employed as the foundational structure to identify, address, and assist a community of irregular migrants attending English‐speaking worship services at a multicultural church in central Madrid. The majority of irregular migrants are sub‐Saharan African and South American. Adult males make up 70% of the population, with 30% being women and children. All irregular migrants attending worship services report being Christian; no data were collected to differentiate between Catholic and Protestant faiths. The irregular migrant community socializes routinely amongst themselves before and after church services as well as outside of church services (bonding social capital). The influential members of their community, such as spiritual leaders and tribal chiefs, interact with the religious leader of the church and the church's council members (bridging social capital). Interaction between church members of both regular and irregular status occurs during church services, religious education classes, bible study classes, language classes, and a coffee hour after church. Through these formal and informal activities, the church has become a place for spiritual, social, and emotional support as well as a location to access food and clothing for irregular migrants through Cáritas.

When Spanish law banned irregular migrants from healthcare services in the national healthcare system, the church community witnessed the negative effect of limited healthcare access. Irregular migrants are part of the social community of the church, so being unable to access health care posed a threat to not only the irregular migrants’ health but the church community's health as well. Therefore, the decision was made to use linking social capital to improve access to healthcare services for irregular migrants to maintain community health.

Work for the program began with bridging social capital to identify civic groups for collaboration. The parish nurse scheduled meetings with local NGOs (e.g., Yo Si Sanidad Universal), humanitarian organizations (e.g., Red Cross), and charity organizations (e.g., Cáritas) to identify systems already in place. Conversations addressed available services, distribution of services, and perceived barriers that kept targeted populations from accessing services.

Following the use of bridging social capital at the professional level, bridging social capital was employed again at the church level between the church leaders and the irregular migrant leaders. Gaining entrance into the community and creating a trusting relationship were the main objectives of these meetings. Discussions involved the perceived needs of the irregular migrant community, which services were most valued by the community (primary, secondary, or tertiary care), and perceived barriers in accessing the services. Meetings were continued until an agreed process, location, time, and access point were mutually determined by all parties. The religious leader of the church, who evokes trust and respect among the irregular migrants, was a significant gate keeper, allowing access to the spiritual and tribal leaders as well as access to a physical location to distribute services.

The bridging social capital meetings informed and directed further meetings to assess strategies and resources to meet the needs of the communities involved. Main themes included ways to address and eliminate or reduce the barriers identified by the service providers and the irregular migrant community. Based on these conversations, an inventory of resources available, the volunteers present, and anticipated financial needs were collected.

Funding was secured through private donations. A charitable foundation was legally structured, according to local law, to manage the financial and legal issues related to the program. Initial ideas for the program included: (a) appointments on Sunday mornings at the church, before worship services to lower transportation costs; (b) an appointment sheet posted in a private area where interested parties could sign up for 10‐min appointments slots; (c) a private office space for appointments with an external entrance to allow private entrance and exit; (d) an office space located next to a restroom for access to water; (e) no financial handouts for medication or supplies would be distributed, but the physical distribution of necessary medication and supplies would be given directly to the client; and (f) intentional and specific collaboration with NGOs, humanitarian agencies, and charities would begin on the bridging social capital level and move towards linking social capital as trust and respect increased between the organization and individuals seeking assistance.

Overview of the Program

The program provides direct assessment for basic health ailments that can be managed on an outpatient basis with immediate distribution of medications or supplies for symptomatic treatment. Monitoring of health conditions, such as high blood pressure, is also performed. Each office visit includes health education as a health support. Additionally, health promotion seminars, which are adapted to the needs of low‐literacy and low‐numeracy learners, are created and implemented on a regular basis. After the seminar, individual bags containing supplies referenced in the seminar and a low‐literacy, low‐numeracy teaching sheet are distributed to participants.

Finally, through linking social capital, the program acts as a triage and referral to link irregular migrants with NGOs, humanitarian groups, and charity organizations. After trust and mutual respect have been cultivated between the nurse and client, the suggestion to access appropriate services and charities is considered safe by the irregular migrant. As Skiba‐King (2016) clearly wrote, “when nurses listen to the . . . undocumented migrant, we are establishing caring connections—we are creating new stories to flood the community” (p. 325).

The program began in November 2012. Initially, only a few irregular migrants came. Culturally, there was a huge divide between the White, educated women providing services and the irregular migrant men seeking services. A warm, inviting presence was necessary while maintaining a professional approach. A white coat was worn by providers and a desk separated the provider from the client to discuss the issue of concern before the examination. Confidentiality was reinforced at each visit, truth keeping was a requirement, as was honoring the needs of the client before our assessment of needs by listening and seeking understanding.

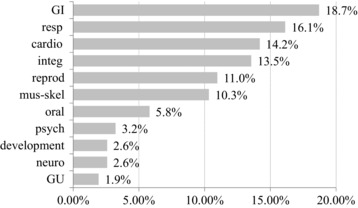

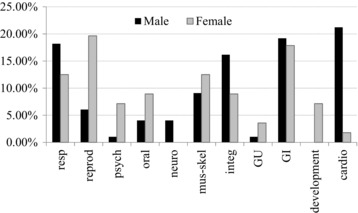

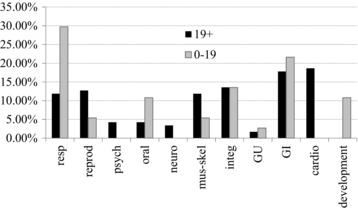

The program sees approximately 10 families per week. Twenty percent of visits each week are to address chronic conditions or are follow‐up visits. Males make up 64% of the clients; 76% of the clients are adults, 5% adolescents, and 19% infants and children. The majority of visits are related to common ailments such as gastrointestinal concerns, respiratory infections, hypertension, and skin infections. Figure 1 shows the distribution of visits by body system. The nature of visits by gender and age are described in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of chief complaints by body system.

Figure 2.

Chief complaint by body system separated by gender.

Figure 3.

Chief complaint by body system separated by age group.

Irregular migrants are referred to outside resources for more severe health impairments, such as suspected broken bones, abnormal growths, uncontrolled hypertension, severe lacerations, sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancy, birth control, and psychiatric issues. Nineteen percent of clients are referred for further evaluation or treatment. Of that 19%, 15% require continued follow‐up.

Through linking social capital, irregular migrants feel confident seeking outside resources to meet their needs. A specific process is employed when clients are referred to outside resources because most irregular migrants do not have sufficient language skills to communicate their needs. Additionally, there can be fear and distrust of seeking services beyond the church. To begin, a note is written at the sixth grade English level and read to the client so they understand what information they are carrying. An opportunity is given to clarify doubts or add additional information. Then, this information is rewritten in Spanish to assist the person receiving the client at the referred location. Finally, an email is sent to the receiving organization to make them aware that a client will be arriving with limited language skills, but carries a letter from our program to help them access the services he or she needs. This is possible because formal lines of communication were created during the development of the program through bridging social capital. The last step is to inform the irregular migrant of the exact location of the service provider and specific directions on how to use the public transportation system to arrive at the location at the right time and on the right day. A follow‐up visit is encouraged with the client after his or her referral to learn more about his or her experience and to provide information to improve the process. Most clients are happy to participate in the improvement process and share positive experiences readily with their community members through bonding social capital.

Lessons Learned

Not all initial ideas worked due to cultural issues. The sign‐up form for appointments was never used. Instead, there is an informal “line” for appointments. When irregular migrant community members were asked why the sign‐up sheet did not work, two reasons were given: (a) not all members could write their English name clearly, and (b) there is a cultural norm of not showing weakness. The irregular migrants did not want other members of their community to know they were seeking support. Another issue related to privacy arose around the distribution of medication and medical supplies. The clients wanted the medications and supplies needed for treatment, but did not want others to see what they were receiving. Having a pharmacy bag to put the medications in, for privacy reasons, was very important to the community.

Beyond physical health needs, irregular migrant community members actively seek information on secondary health issues such as nutrition, child development and discipline, grief and loss, exercise and healthy behaviors, and clarifying culturally learned health behaviors (i.e., questions such as: How long do you have to wait between users of public restrooms to allow the air to change?). This prompted the need to connect with other health professionals to find appropriate resources and information.

Challenges

There are still issues that have not been resolved. One issue is the hierarchy between men and women; women will be in the invisible line, but men will jump ahead of them. The last meetings of the morning are always women and their children. Additionally, there have been issues of trying to seek more medication than necessary, seeking medications for afflictions not being experienced, or bringing in an empty medication container and demanding the exact same medication to be distributed.

Another challenge is guiding the expectations of the client. Educating clients that health impairments are not always resolved with the first medical appointment or first therapy is critical to maintaining a trusting relationship and avoiding skepticism of the program. Correspondingly, follow‐up can be difficult among a transient population, which can affect medication therapies, monitoring health conditions, or knowing if certain procedures were effective.

There has been a rotation of volunteer providers. Working with irregular migrants is demanding. Issues that influence volunteers are: (a) a lack of a shared native language between the nurse and client so there can be misunderstandings about what is being expressed; (b) power differential can be uncomfortable when strong personalities interact; (c) power struggles can arise; (d) fairness is culturally assessed and clients can complain about services; and (e) when a service is “free” there can be feelings of entitlement, which can be demoralizing for the providers.

Positive Outcomes

Despite the challenges, there are rewards. The irregular migrant community reports feeling supported and is better able to access services it previously did not know were available or were uncertain how to access. Specific examples include: (a) two women and one man being successfully treated for sexually transmitted diseases from a foundation specializing in sexual health education; (b) a woman was able to access services to address an unwanted pregnancy and obtain birth control by two distinct foundations providing women's health services; (c) a man was able to receive appropriate diagnostic testing, treatment, and follow‐up for a cerebral vascular accident related to uncontrolled hypertension from a humanitarian organization. This individual now has his daily medication purchased and distributed by the program as well as weekly follow‐up to prevent a reoccurrence; and (d) a man with an abdominal tumor was able to access an evaluation and treatment within the national healthcare system through the assistance of an NGO that accompanied him to his doctor visit and assured he was adequately evaluated. In all these cases, the irregular migrants were previously unaware of available services, were unable to access the services due insufficient language skills, or did not have sufficient trust to visit these services without the direct and repeated assurance of the program members. Linking social capital was integral in helping the irregular migrants know, understand, and access services that are available in the community to meet their healthcare needs.

Additionally, the parish community is better protected from preventable communicable disease. Health promotion seminars on proper handwashing use and technique help lower the spread of gastrointestinal illnesses. Prompt and appropriate treatment of intestinal worms limits the spread between household members and other community members outside the household. Health promotion seminars on healthy eating are well attended by both irregular migrants and local community members to improve health and well‐being. Through these shared experiences and shared concern for each other, increasing networks of bonding and bridging social capital among church community members reinforce the benefits from providing linking social capital to the irregular migrant community.

Conclusions

This novel strategy of employing Wald's grassroots approach can be recreated by nurses in their local communities to start caring for the unseen. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948, 1966a, 1966b) clearly entitles all humans, regardless of status, to basic human rights, which includes health care. Violence, conflict, and extreme poverty continue to force migration globally; migrants who choose irregular entry are at higher risk for health impairments due to lack of social capital (European Migration Network, 2014; Wermuth, 2003).

Nurses have the ability to build positive relationships with irregular migrants based on safe interactions in order to assist them in meeting their healthcare needs (Skiba‐King, 2016). The use of linking social capital between nurses and irregular migrants, stemming from a trusting and respectful nurse–patient relationship, can improve access and healthcare outcomes for both the irregular migrant community and the larger community as a whole (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). Furthermore, nurse‐led efforts to meet irregular migrant health needs and scholarly documentation of these efforts directly support the global nursing research priorities set by Sigma Theta Tau International (2005) which include health promotion and disease prevention as well as advocacy and promotion of health of vulnerable and marginalized communities.

Clinical Resources.

European Migration Network: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home‐affairs/financing/fundings/migration‐asylum‐borders/asylum‐migration‐integration‐fund/european‐migration‐network/index_en.htm

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: http://fra.europa.eu/en

References

- Afzali, M. , Shahhosseini, Z. , & Hamzeghardeshi, Z. (2015). Social capital role in managing high risk behavior: A narrative review. Materia Socio Medica, 27(4), 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitoulas, A. (2015). Eurostat data in focus: Population and social conditions 3/2015 Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/4168041/6742650/KS-QA-15-003-EN-N.pdf/b7786ec9-1ad6-4720-8a1d-430fcfc55018

- Cáritas Española. (2009a). Cáritas: Preguntas frecuentes [Cáritas: Frequently asked questions]. Retrieved from http://www.caritas.es/PreguntasFrecuentes.aspx

- Cáritas Española. (2009b). Cáritas: Programas de desarrollo social. Acogida, atención primaria y atención de base [Cáritas: Social development programs, shelter services, primary care and basic needs services]. Retrieved from http://www.caritas.es/qhacemos_programas.aspx

- Clandestino. (2009). Irregular migration in Spain: Counting the uncountable—Data and trends across Europe European Commission. Retrieved from http://www.eliamep.gr/wp‐content/uploads/en/2009/04/research_brief_spain.pdf

- Clandestino. (2012). Database on irregular migration European Commission. Retrieved from http://irregular-migration.net

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control . (2015). Expert opinion on the public health needs of irregular migrants, refugees or asylum seekers across the EU's southern and south‐eastern boarders. Stockholm: Author; Retrieved from http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Expert‐opinion‐irregular‐migrants‐public‐health‐needs‐Sept‐2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . (2012). Special Eurobarometer 386: Europeans and their languages Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf

- European Migration Network . (2011). Ad‐hoc query on national definitions of irregular migrants and available data. Paris, France: National Network Conference; Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/reports/docs/ad‐hoc‐queries/298.emn_ad‐hoc_query_irregular_migration_updated_wider_dissemination_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- European Migration Network . (2014). Asylum and migration glossary 3.0: A tool for better comparability European Commission. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/docs/emn-glossary-en-version.pdf

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights . (2011). Fundamental rights of migrants in an irregular situation in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/1827-FRA_2011_Migrants_in_an_irregular_situation_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . (2011). Demography report 2010: Older, more numerous and diverse Europeans Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=502&newsId=1007&furtherNews=yes

- Gittell, R. , & Thompson, J. P. (2001). Making social capital work: Social capital and community economic development In Saegert S., Thompson J. P., & Warren M. R. (Eds.), Social capital and poor communities (pp. 115–135). New York, NY: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno España de. (2012). Real Decreto‐Ley 16/2012 de 20 de abril, de medidas urgentes para garantizar la sostenibilidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud y mejorar la calidad y seguridad de susprestaciones [Royal decree law, on April 20, 2012, of urgent measures to guarantee the sustainability of the national health care service and to improve the quality and safety of services].

- Islam, M. K. , Merlo, J. , Kawachi, I. , Lindstrom, M. , & Gerdtham, U.‐G. (2006). Social capital and health: Does eqalitarianism matter? A literature review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 5(3). doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-5-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I. (2001). Social capital for health and human development. Development, 44(1), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. S. (1996). The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty‐first century. Demography, 33(4), 395–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, H. , Fujiwara, Y. , & Kawachi, I. (2012). Social capital and health: A review of prospective multilevel studies. Journal of Epidemiology, 22(3), 179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguera, P. A. (2001). Transforming urban schools through investment in the social capital of parents In Saegert S., Thompson J. P., & Warren M. R. (Eds.), Social capital and poor communities (pp. 189–212). New York, NY: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Shattell, M. (2004). Nurse‐patient interaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(6), 714–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigma Theta Tau International . (2005). Resource paper of global health and nursing research priorities Retrieved from https://www.nursingsociety.org/docs/default-source/position-papers/position_ghnrprp-(1).pdf?sfvrsn=4

- Skiba‐King, E. (2016). Undocumented immigrants: Connecting with the disconnected In de Chesnay M. & Anderson B. A. (Eds.), Caring for the vulnerable: Perspectives in nursing theory, practice, and research (4th ed., pp. 321–328). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter, S. , & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

- United Nations . (1966a). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20999/volume-999-I-14668-English.pdf [PubMed]

- United Nations . (1966b). International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

- United Nations . (2015). United Nations Human Rights: UPR mid‐term reports Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/UPR/Pages/UPRImplementation.aspx

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . (2015). Mediterranean crossings in 2015 are already top 100,000 The UN Refugee Agency. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2015/6/557703c06/mediterranean-crossings-2015-already-top-100000.html

- Wald, L. (1915/2014). The house on Henry Street. London, England: Forgotten Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wermuth, L. (2003). In Hanson K. (Ed.), Global inequality and human needs: Health and illness in an increasingly unequal world. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yo Si Sanidad Universal . (2015). Retrieved from http://yosisanidaduniversal.net/portada.php

- Yost, E. (1955). American women of nursing. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Co. [Google Scholar]