Abstract

Total pancreatectomy is associated with short- and long-term high complication rate and without evidence of oncologic advantages. Several metabolic consequences are co-related with the apancreatic state. The unstable diabetes related to the total resection of the pancreas expose the patients to short- and long-term life-threatening complications. Severe hypoglycemia is a short-term dangerous complication that can also cause patients’ death. Chronic complications of severe diabetes (cardiac and vascular diseases, neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy) are also cause of morbidity, mortality and worsening of quality of life. For this reasons the number of total pancreatectomies performed has certainly decreased over time. However, today there are still some indications for this kind of procedures. Chronic pancreatitis untreatable with conventional treatments, surgical treatment of precancerous pancreatic lesions, surgical treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer and the management of patients with extraordinary high-risk pancreatic texture after pancreaticoduodenectomy represent possible indications for total pancreatectomy and are analyzed in the present paper.

Keywords: Total pancreatectomy, Pancreas surgery, Arterial resection, Pancreatectomy

Introduction

At the beginning of the era of oncologic pancreatic surgery, total pancreatectomy (TP) was used as a “radical procedure” for the surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer [1, 2]. However, new insights on pancreatic oncology, associated with the evidence of the side effects of total pancreatectomy, have made this procedure less appealing. The short- and long-term morbidity and mortality associated with the apancreatic state affecting these patients continue to be of concern today [3]. For these reasons, the complete removal of the pancreas is not considered today a more “radical” operation for patients suffering from pancreatic cancer and it cannot be considered the standard of care for the surgical treatment of these patients [4].

Even if the number of total pancreatectomies performed has certainly decreased over time, today there are still some indications for this procedure. Most of these are based more on local or personal experience rather than on true evidence and some data even show that the short- and long-term results of TP are not much different than undergoing a partial resection of the pancreas. A recent matched-pairs analysis of TP and pancreaticoduodenectomy, for example, revealed similar surgical outcome and long-term survival [5]. In the last decades, new advances in pancreatic surgery and in medical pancreatology have resulted in a new appraisal of TP as a treatment alternative for some pancreatic diseases or as technical option for some operative procedures.

In recent years, when major attention has been focused on preemptive pancreatic surgery [6], the role of TP has again been reevaluated. At the same time TP is proposed, with or without simultaneous auto-islet transplantation, for some types of chronic pancreatitis [7] and also for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer requiring arterial resection and reconstruction [8]. Total pancreatectomy combined with autologous islet transplantation has also been proposed for patients with a high-risk for complications resulting from the pancreatic anastomosis [9].

The aim of this review paper is to offer a complete overview of the outcome of TPs and to define the current indication for this procedure.

Outcome of total pancreatectomy

Surgical outcome

Generally, TP is considered a safer procedure than pancreaticoduodenectomy in the perioperative setting since a pancreatico-jejunostomy is not required. This implication is the basis for concept that TP may be an option for patients with a normal pancreas and a very high-risk for leakage after reconstruction, to prevent major postoperative complications. This theory has anyhow not been confirmed by the literature data. A recent analysis made on the US National Cancer Data Base [10] on 2582 patients who underwent TP for pancreatic cancer showed a 30-day mortality rate of 5.5 %. The same rate of short-term mortality was observed by Billings and co-authors [11] in a series of 99 consecutive TP, with the addition of 3 % of late death related to hypoglycemic episodes. The same authors investigated also the long-term QoL of 27 patients included in the study, showing a decrease of QoL compared with age- and gender-matched controls, but not compared to patients with diabetes from other causes. Even analyzing the recent data from the literature, it is quite evident that TP are associated with a significant postoperative morbidity and mortality, not inferior to partial pancreatectomy, as showed in Table 1 [5, 9, 10, 12–17].

Table 1.

Short-term outcome of patients underwent TP

| Author | Year | # Patients | # IAT | Overall morbidity (%) | Overall mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnston PC | 2016 | 2582 | N.A. | N.A. | 5.5 |

| Balzano G | 2015 | 28 | 28 | 57.1 | 7.1 |

| Satoi S | 2015 | 45 | – | 31.1 | – |

| Chinnakotla S | 2015 | 518 | 518 | N.A. | 9.2 |

| Johnston PC | 2015 | 18 | 18 | 50 | N.A. |

| Wantabe Y | 2015 | 23 | – | 43 | 4 |

| Datta J | 2015 | 64 | – | 45.3 | 1.6 |

| Hartwig W | 2015 | 434 | – | 37.6 | 7.8 |

| Almond M | 2014 | 80 | – | 46 | 12.5 |

| Nikfarjam M | 2014 | 15 | – | 87 | 8 |

Metabolic consequences of total pancreatectomy

Several metabolic consequences are co-related with the apancreatic state, which characterizes the patients who underwent TP. Certainly, the most known and investigated sequel is diabetes. As defined by the American Diabetes Association, patients who underwent TP suffer from a type 3c diabetes, also called pancreatogenic diabetes [18]. In this form of diabetes, the glycemic control may be labile due to the loss of not only the insulin production, but particularly due to the loss of glucagon secretion [19]. The combination of insulin sensitivity and hypoglycemic unawareness, characteristic of this condition, is known as “brittle” diabetes [20]. It exposes patients who have undergone TP to short- and long-term life-threatening complications. In a recent series from Mayo Clinic, the large majority of patients undergoing TP (89 %) required a complex insulin regimen to maintain acceptable glycemic control. Seventy nine of them experienced episodes of hypoglycemia and 41 % of severe hypoglycemia. The resuscitation of these patients was possible by family members or co-workers only in 27 % of the cases, while the remaining 73 % required medical intervention or hospitalization [3]. Significant late mortality (3 %) due to hypoglycemic episodes has been reported by other authors [11]. The nonoptimal glycemic control is also the cause for chronic complications in the specific target organs. In the Mayo Clinic, the total cohort of patients who underwent TP experienced retinopathy in 3 %, neuropathy in 5 %, nephropathy in 4 %, cerebrovascular diseases in 1 %, cardiovascular diseases in 11 % [3].

The medical treatment of type 3c diabetes may be challenging. Insulin infusion pumps seem to improve the glycemic control and reduce the attacks of hypoglycemia [21]. However, evidence is lacking on the effect of this kind of treatment on the long-term complications of diabetes. The addition of glucagon injection to the insulin regimen seems to be advantageous in reducing the hypoglycemic episodes, but so far, only limited evidence about its usage is available [22].

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) is another consequence of TP. Even with high dose of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, a significant part of the patients who have undergone TP still suffer from steatorrhea, with consequent malabsorption, thus complicating further the already fragile management of diabetes [23]. PEI requires a lifelong substitutive treatment with pancreas enzymes [24]. However, the enzyme substitution in the majority of patients might not be enough to completely restore the normal digestion. A considerable number of the patients are thus undertreated for this problem, with underestimated and undiagnosed subclinical malnutrition even in the absence of steatorrhea [25]. Furthermore, alteration of the gastrointestinal motility is a well-known digestive disturbance associated with the development of severe exocrine insufficiency, but its role in post-pancreatectomy patients has not been investigated.

Liver steatosis is another complication considered to be associated with TP. It has been demonstrated that it may result in liver failure in some patients [26].

Quality of life (QoL) after total pancreatectomy

QoL after TP is a very difficult topic to investigate and elaborate on. There are several and different instruments for the QoL measurement. The indications for TP and its associated procedures (i.e., auto-islet transplantation) are also several and different, as well as the initial condition of the patients and the expected long-term results and functionality, making it difficult to unequivocally apply all these instruments. In a recent small series Watanabe defined the QoL of a group on patients who underwent TP comparable to those of the national population, excluding for one third of the patients that experienced diarrhea [14]. Billings and colleagues [11] investigated the QoL of 34 patients who underwent total pancreatectomy with three different audit systems (SF-36, ADD QoL and EORTC PAN-26). They concluded that QoL after pancreatectomy is decreased compared with the age- and gender- matched controls, but not with diabetic patients for other causes.

Indications for total pancreatectomy

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive chronic inflammation of the pancreas that can be caused by several etiological factors. Currently, a step-up approach (medical treatment, endoscopic treatment, surgical treatment) for patients suffering from CP has been recommended to be the standard of care. The most common consequences of chronic pancreatitis are abdominal pain and exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. In case when the pain is associated with ductal dilatation, a decompressive procedure is indicated. In these cases surgery seems to be superior to endoscopy according to recent studies [27]. In the case of “small-duct” CP in patients resistant to medical treatment, TP with or without auto-islet transplantation has been proposed [28, 29]. The same indication is present for patients with hereditary pancreatitis who are at increased risk for cancer development.

TP with auto-islet transplantation has received increasing attention recently. The concept behind this approach is interesting, because the procedure seems to be safe and theoretically able to maintain good glycemic control, thus avoiding one of the devastating complications of TP [30]. The rate of insulin independence after auto-islet transplantation ranges between 24 and 40 % in the largest series as reported in Table 2 [28, 31–33]. For further, one third of the patients partial insulin dependence is achieved providing a better and more stable glycemic control. One of the most important predictor factors of insulin independence seems to be the quantity of the transplanted islets [28, 33]. For this reason, the timing of surgery for chronic pancreatitis is essential. Thus, in patients considered as candidates for TP with auto-islet transplantation, surgery should perhaps be considered earlier and certainly before the endocrine function is compromised. Furthermore, this procedure has shown even benefits in terms of the pain control. In other series, the range of pain-free or narcotic-independent patients is reported to be from 59 % to 80 % [28, 32]. The pain control seems to be stable over time, too. Ong and co-workers [31] reported that only 16 % of patients who underwent TP with auto-islet transplantation needed opiates at 5 years. For patients with chronic pancreatitis who have with maintained endocrine function but pain resistant to medical, endoscopic and surgical treatment, this option has shown also an improved quality of life [32].

Table 2.

Outcome of total pancreatectomy + auto-islet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis

| Author | Year | # Patients | Insulin independent (%) | Partial function (%) | Insulin dependent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutherland DR | 2012 | 409 | 30 (3 years) | 33 (3 years) | 37 (3 years) |

| Walsh RM | 2012 | 20 | 20 (not specified) | – | 80 % (not specified) |

| Ong SL | 2009 | 50 | 40 (post-op) | – | – |

| Ahmad S | 2005 | 118 | 40 (not specified) | – | 60 (not specified) |

Premalignant lesions

TP has been proposed as a preemptive treatment for patients with a familial risk for pancreatic cancer [34]. Today, however, the prophylactic removal of the pancreas in individuals with a family history of pancreatic cancer is not recommended by neither national nor international guidelines [35, 36]. Rather, the treatment of detected precancerous lesions is advised, by partial pancreatic resections. However, unlike IPMNs, Pan-INs still cannot be detected by the current imaging modalities. This has raised the concern that undetected precancerous lesions might be left behind in the residual pancreas, thus leaning the choice towards TP. In case of abnormalities diffusely involving the pancreatic gland, in young patients and with high familial risk, though, a total pancreatectomy might be considered [37].

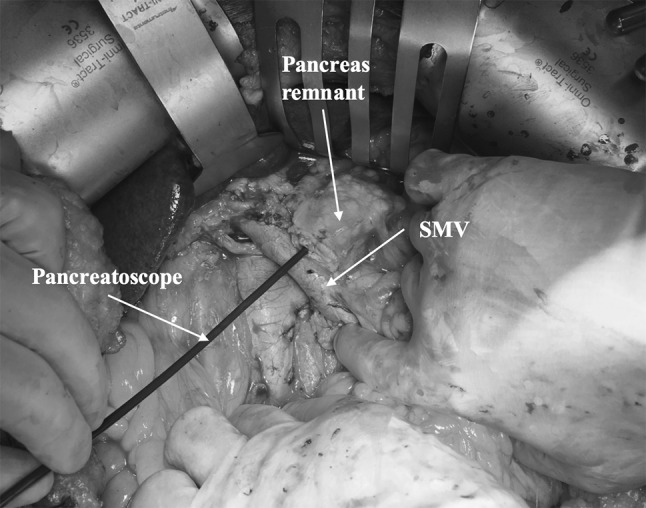

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMNs) also comprise precancerous lesions that potentially can progress into cancer. In accordance with the emerging literature data and with the European and International Guidelines, the majority of branch-duct IPMNs can be managed conservatively without the need for surgical resection [38, 39]. In contrast, the main-duct IPMNs require resection in every patient fit for surgery [38, 39]. There is emerging evidence in the literature supporting the indication for surgery even for relatively small dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, as recommended by the European Guidelines on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas [40, 41]. When the dilatation of the duct is confined to a certain segment, a partial pancreatectomy with a frozen section of the resection margin is recommended [38]. The situation is more complicated when the entire duct is dilated. In this case, generally a pancreaticoduodenectomy with a frozen section of the resection margin is advocated to determine the extent of the resection [38]. The only scenario when total pancreatectomy is recommended is in case of diffusely extensive disease, with an advanced stage of dysplasia present in the entire duct. How reliable the frozen section is in determining the extent of the grossly dysplastic changes in the duct is questionable, and for sure, “skip lesions” of the main pancreatic duct can be missed. Pancreatoscopy, pre- or intraoperatively, can improve the accuracy of defining the extent of the disease and potentially better help select the candidates for a total pancreatectomy [42] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Picture of intraoperative pancreatoscopy. The pancreatoscope is inserted in the main pancreatic duct after the transection of the pancreatic neck in a pancreaticoduodenectomy procedure performed for main-duct IPMN. SMV superior mesenteric vein

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer

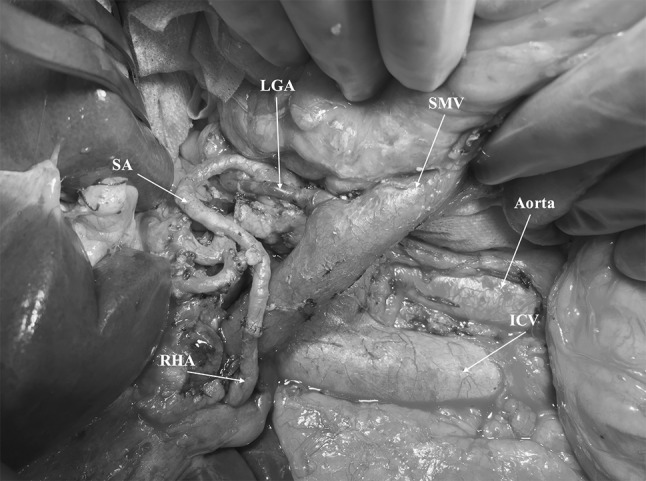

Even if the surgical treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer is currently not the standard of care, it did receive more attention recently in the light of the more promising results of new neoadjuvant treatments [43]. In selected cases, surgery for locally advanced pancreatic cancer is also supported by the international scientific community [44]. When an arterial resection is required, the transposition or interposition of the splenic artery can, for instance, be used for the reconstruction both of the hepatic and superior mesenteric arteries [8, 46] (Fig. 2). In cases when arterial reconstructions are undertaken, TP is generally performed [8, 45]. The complete removal of the pancreas makes the procedure safer by eliminating completely the problem of pancreas fistula and it’s potentially fatal effect on the arterial anastomosis.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative picture of total pancreatectomy associated with resection of the right hepatic artery (RHA) and reconstruction with the splenic artery (SA) rotated. LGA left gastric artery, ICV inferior cava vein, SMV superior mesenteric vein

High-risk pancreatic anastomosis

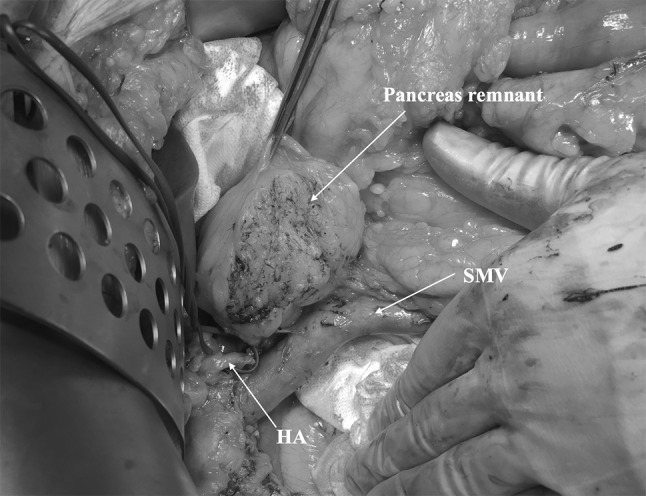

A soft pancreatic texture and a small main pancreatic duct represent the major risk factors for the development of postoperative pancreatic fistula and these can easily be evaluated pre- and intraoperatively [47]. Overweight and pancreatic fat infiltration are other well-recognized predictors for the risk of postoperative fistula [48] and can as well create a technical problem in making the pancreatic anastomosis (Fig. 3). In selected cases of very high-risk patients, with a high-risk pancreas and other contributing risk factors, TP may represent an alternative to a pancreatic anastomosis in an attempt to reduce the significant postoperative morbidity and mortality. This approach has been proposed recently, even in a conjunction to auto-islet transplantation [9]. However, this decision should be always weighted against the risks associated with TP, as the postoperative mortality and morbidity (Table 1) of TP are significant as well as the long-term sequels of this operation [3].

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative picture showing a totally fat-infiltrated pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HA hepatic artery, SMV superior mesenteric vein

Discussion

In the last years, the number of the performed TP for the treatment of pancreatic diseases has been reduced in all high-volume pancreatic centers. There are several reasons for sustaining this trend. First of all, in oncologic surgery, there is no evidence that TP represents a more radical oncologic procedure [4]. [3]. In contrast, TP is associated with short- and long-term serious sequels and complications due to the “brittle” diabetes – 3 % late mortality caused by severe hypoglycaemia and chronic complications in the target organs.

However, even today, TP has its role in pancreatic surgery for some limited indications. As previously discussed, for patients affected by chronic pancreatitis, in whom the conventional medical and surgical approaches have failed, TP can represent the only therapeutic alternative, particularly, in association with auto-islet transplantation [10, 13] with encouraging results for pain, metabolic control and postoperative quality of life. The quantity of the islet cells and the timing of the procedure are crucial for the success of the auto-islet transplantation.

TP for the treatment of precancerous lesions has been decreasingly recommended as upfront approach, but rather partial resections, with intraoperative frozen section of the resection margin and/or pancreatoscopy to preserve pancreatic parenchyma [42]. However, in selected cases with diffuse dysplastic changes in the duct, TP still represents the best alternative for patients with main-duct IPMN.

In our experience, TP represents the best choice for patients who undergo pancreatectomy with arterial resections and reconstructions. The complete removal of the pancreas eliminates the risk of pancreatic fistula leading potentially to postoperative pseudoaneurysms and late erosive bleedings in the presence of simultaneous arterial anastomosis.

TP cannot be considered an equal alternative to pancreatic anastomosis to reduce the pancreas remnant complications, even with auto-islet transplantation, according to the current level of evidence in literature. However, in selected patients in poor general conditions, and with very high-risk pancreas and obese, TP may represent an adequate alternative technique [9].

In conclusion, even if the indications for TP have been consistently reduced over time, even today this procedure still has its place. The improvement of short- and long-term results of TP when combined with auto-islet transplantation may expand the spectrum of indication for this procedure in the near future.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Rockey EW. Total pancreatectomy for carcinoma: case report. Ann Surg. 1943;118:603–611. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194310000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaston EA. Total pancreatectomy. N Engl J Med. 1948;238:345–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194803112381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsaik AK, Murad MH, Sathananthan A, Moorthy V, Erwin PJ, Chari S, Carter RE, Farnell MB, Vege SS, Sarr MG, Kudva YC. Metabolic and target organ outcomes after total pancreatectomy: Mayo Clinic experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Endocrinol. 2010;73:723–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almond M, Roberts KJ, Hodson J, Sutcliffe R, Marudhanayagam R, Isaac J, Muiesan P, Mirza D. Changing indications for a total pancreatectomy: perspectives over a quarter of a century. HPB Off J Int Hepato Pancreatol Biliary Assoc. 2015;17:416–421. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoi S, Murakami Y, Motoi F, Sho M, Matsumoto I, Uemura K, Kawai M, Kurata M, Yanagimoto H, Yamamoto T, Mizuma M, Unno M, Kinoshita S, Akahori T, Shinzeki M, Fukumoto T, Hashimoto Y, Hirono S, Yamaue H, Honda G, Kwon M. Reappraisal of total pancreatectomy in 45 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the modern era using matched-pairs analysis: multicenter study group of pancreatobiliary surgery in Japan. Pancreas. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Chiaro M, Segersvard R, Lohr M, Verbeke C. Early detection and prevention of pancreatic cancer: is it really possible today? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12118–12131. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i34.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Q, Zhang M, Qin Y, Jiang R, Chen H, Xu X, Yang T, Jiang K, Miao Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of islet autotransplantation after total pancreatectomy in chronic pancreatitis patients. Endocr J. 2015;62:227–234. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ14-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hackert T, Weitz J, Buchler MW. Splenic artery use for arterial reconstruction in pancreatic surgery. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2014;399:667–671. doi: 10.1007/s00423-014-1200-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balzano G, Maffi P, Nano R, Mercalli A, Melzi R, Aleotti F, Zerbi A, De Cobelli F, Gavazzi F, Magistretti P, Scavini M, Peccatori J, Secchi A, Ciceri F, Del Maschio A, Falconi M, Piemonti L. Autologous islet transplantation in patients requiring pancreatectomy: a broader spectrum of indications beyond chronic pancreatitis. Am J Transplant. 2015;16:1812–1826. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston WC, Hoen HM, Cassera MA, Newell PH, Hammill CW, Hansen PD, Wolf RF. Total pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: review of the National Cancer Data Base. HPB Off J Int Hepato Pancreato Biliary Assoc. 2016;18:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billings BJ, Christein JD, Harmsen WS, Harrington JR, Chari ST, Que FG, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Sarr MG. Quality-of-life after total pancreatectomy: is it really that bad on long-term follow-up? J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2005;9:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinnakotla S, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Radosevich DM, Arain M, Amateau SK, Mallery JS, Schwarzenberg SJ, Clavel A, Wilhelm J, Robertson RP, Berry L, Cook M, Hering BJ, Sutherland DE, Pruett TL. Factors predicting outcomes after a total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation lessons learned from over 500 cases. Ann Surg. 2015;262:610–622. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston PC, Lin YK, Walsh RM, Bottino R, Stevens TK, Trucco M, Bena J, Faiman C, Hatipoglu BA. Factors associated with islet yield and insulin independence after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation in patients with chronic pancreatitis utilizing off-site islet isolation: cleveland Clinic experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2015;100:1765–1770. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe Y, Ohtsuka T, Matsunaga T, Kimura H, Tamura K, Ideno N, Aso T, Miyasaka Y, Ueda J, Takahata S, Igarashi H, Inoguchi T, Ito T, Tanaka M. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy: special reference to survivors’ living conditions and quality of life. World J Surg. 2015;39:1231–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2948-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta J, Lewis RS, Jr, Strasberg SM, Hall BL, Allendorf JD, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Callery MP, Christein JD, Drebin JA, Epelboym I, He J, Pitt HA, Winslow E, Wolfgang C, Lee MK, 4th, Vollmer CM., Jr Quantifying the burden of complications following total pancreatectomy using the postoperative morbidity index: a multi-institutional perspective. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Sur Aliment Tract. 2015;19:506–515. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2706-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartwig W, Gluth A, Hinz U, Bergmann F, Spronk PE, Hackert T, Werner J, Büchler MW. Total pancreatectomy for primary pancreatic neoplasms: renaissance of an unpopular operation. Ann Surg. 2015;261:537–546. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikfarjam M, Low N, Weinberg L, Chia PH, He H, Christophi C. Total pancreatectomy for the treatment of pancreatic neoplasms. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:823–826. doi: 10.1111/ans.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Americal Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S62–S67. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen DK, Andren-Sandberg A, Duell EJ, Goggins M, Korc M, Petersen GM, Smith JP, Whitcomb DC. Pancreatitis-diabetes-pancreatic cancer: summary of an NIDDK-NCI workshop. Pancreas. 2013;42:1227–1237. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182a9ad9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tattersall RB. Brittle diabetes revisited: the third arnold bloom memorial lecture. Diabetic Med J Br Diabetic Assoc. 1997;14:99–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199702)14:2<99::AID-DIA320>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radermecker RP, Scheen AJ. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion with short-acting insulin analogues or human regular insulin: efficacy, safety, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness. Diabetes Metabol Res Rev. 2004;20:178–188. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanjoh K, Tomita R, Mera K, Hayashi N. Metabolic modulation by concomitant administration of insulin and glucagon in pancreatectomy patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:538–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahl S, Malfertheiner P. Exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:947–955. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6918(04)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabater L, Ausania F, Bakker OJ, Boadas J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Frulloni L, Gonzalez-Sanchez V, Larino-Noia J, Lindkvist B, Lluis F, Morera-Ocon F, Martin-Perez E, Marra-Lopez C, Moya-Herraiz A, Neoptolemos JP, Pascual I, Perez-Aisa A, Pezzili R, Ramia JM, Sanchez B, Molero X, Ruiz-Montesinos I, Vaguero EC, de-Madaria E. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikkens EC, Cahen DL, van Eijck C, Kuipers EJ, Bruno MJ. Patients with exocrine insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis are undertreated: a Dutch national survey. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol (IAP) 2012;12:71–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dresler CM, Fortner JG, McDermott K, Bajorunas DR. Metabolic consequences of (regional) total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 1991;214:131–140. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199108000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Laramee P, Nio Y, Rauws EA, Boermeester MA, Busch OR, Fockens P, Kuipers EJ, Pereira SP, Wonderling D, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic vs surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1690–1695. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutherland DE, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, Hering BJ, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Vickers SM, Bland B, Balamurugan AN, Freeman ML, Pruett TL. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Gelrud A, Slivka A, Clavel A, Humar A, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in chronic pancreatitis: recommendations from PancreasFest. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol (IAP) 2014;14:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fazlalizadeh R, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Demirjian AN, Imagawa DK, Foster CE, Lakey JR, Stamos MJ, Hirohito I. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation: a decade nationwide analysis. World J Transplant. 2016;6:233–238. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong SL, Gravante G, Pollard CA, Webb MA, Illouz S, Dennison AR. Total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation: an overview. HPB Off J Int Hepatol Pancreato Biliary Assoc. 2009;11:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh RM, Saavedra JR, Lentz G, Guerron AD, Scheman J, Stevens T, Trucco M, Bottino R, Hatipoglu B. Improved quality of life following total pancreatectomy and auto-islet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Alimentary Tract. 2012;16:1469–1477. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1914-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, D’Alessio D, Choe KA, James LE, Gelrud A, Matthews JB, Rilo HL. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brentnall TA. Cancer surveillance of patients from familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Med Clin N Am. 2000;84:707–718. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Chiaro M, Zerbi A, Capurso G, Zamboni G, Maisonneuve P, Presciuttini S, Arcidiacono PG, Calculli Falconi, M L , Italian Registry for Familial Pancreatic Cancer Familial pancreatic cancer in Italy. Risk assessment, screening programs and clinical approach: a position paper from the Italian Registry. Digest Liver Disease Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. 2010;42:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canto MI, Harinck F, Hruban RH, Offerhaus GJ, Poley JW, Kamel I, Nio Y, Schulick RS, Bassi C, Kluijt I, Levy MJ, Chak A, Fockens P, Goggins M, Bruno M, International Cancer of Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium summit on the management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:339–347. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartsch DK, Dietzel K, Bargello M, Matthaei E, Kloeppel G, Esposito I, Heverhagen JT, Gress TM, Slater EP, Langer P. Multiple small “imaging” branch-duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) in familial pancreatic cancer: indicator for concomitant high grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia? Fam Cancer. 2013;12:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9582-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Kloppel G, Werner J, McKay C, Friess H, Manfredi R, Van Cutsem E, Löhr M, Segersvärd R, European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Vevy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang CL, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, International Association of Pancreatology International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol (IAP) 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hackert T, Fritz S, Klauss M, Bergmann F, Hinz U, Strobel O, Büchler MW. Main-duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm: high Cancer Risk in Duct Diameter of 5 to 9 mm. Ann Surg. 2015;262:875–881. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Chiaro M, Schulick RD. Main-duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm. High Cancer Risk in Duct Diameter of 5–9 mm. Ann Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnelo U, Siiki A, Swahn F, Segersvard R, Enochsson L, Del Chiaro M, Lundell L, Verbeke C, Löhr JM. Single-operator pancreatoscopy is helpful in the evaluation of suspected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol (IAP) 2014;14:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaib WL, Ip A, Cardona K, Alese OB, Maithel SK, Kooby D, Landry J, El-Rayes BF. Contemporary management of borderline resectable and locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:178–187. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartwig W, Vollmer CM, Fingerhut A, Yeo CJ, Neoptolemos JP, Adham M, Andren-Sandberg A, Asbun HJ, Bassi C, Bockhorn M, Charnley R, Conlon KC, Dervenis C, Fernandez-Cruz L, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Imrie CW, Lillemoe KD, Milicevic MN, Montorsi M, Shrikhand SV, Vashist YK, Izbicki JR, Büchler MW, Interational Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery Extended pancreatectomy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: definition and consensus of the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2014;156:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Del Chiaro M, Segersvard R, Rangelova E, Coppola A, Scandavini CM, Ansorge C, Verbeke C, Blomberg J. Cattell-braasch maneuver combined with artery-first approach for superior mesenteric-portal vein resection during pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2015;19:2264–2268. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2958-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aosasa S, Nishikawa M, Noro T, Yamamoto J. Total pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection and hepatic artery restoration using splenic artery autograft interposition. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2016;20:644–647. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frozanpor F, Loizou L, Ansorge C, Lundell L, Albiin N, Segersvard R. Correlation between preoperative imaging and intraoperative risk assessment in the prediction of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2014;38:2422–2429. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tranchart H, Gaujoux S, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Dokmak S, Levy P, Couvelard A, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Preoperative CT scan helps to predict the occurrence of severe pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2012;256:139–145. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256c32c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]