Abstract

The epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stemness (CS) are reported to be pivotal phenomena involved in metastasis, recurrence, and drug‐resistance in lung cancer; however, their effects on tumor malignancy in clinical settings are not completely understood. The mutual association between these factors also remains elusive and are worthy of investigation. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the association between EMT and CS, and their effect on the prognosis of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. A total of 239 lung adenocarcinoma specimens were collected from patients who had undergone surgery at Kyoto University Hospital from January 2001 to December 2007. Both EMT (E‐cadherin,vimentin) and CS (CD133, CD44, aldehyde dehydrogenase) markers were analyzed through immunostaining of tumor specimens. The association between EMT and CS as well as the patients' clinical information was integrated and statistically analyzed. The molecular expression of E‐cadherin, vimentin, and CD133 were significantly correlated with prognosis (P = 0.003, P = 0.005, and P < 0.001). A negative correlation was found between E‐cadherin and vimentin expression (P < 0.001), whereas, a positive correlation was found between vimentin and CD133 expression (P = 0.020). CD133 was a stronger prognostic factor than an EMT marker. Elevated CD133 expression is the signature marker of EMT and CS association in lung adenocarcinoma. EMT and CS are associated in lung adenocarcinoma. Importantly, CD133 is suggested to be the key factor that links EMT and CS, thereby exacerbating tumor progression.

Keywords: Cancer stemness, CD133, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition, lung adenocarcinoma, vimentin

Introduction

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer death worldwide 1, and adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic subtype of primary lung cancer 2. Recently, the therapeutic strategies for lung cancer have been developing and shifting from cytotoxic reagents to molecular‐targeted reagents. However, the evolving mechanisms through which cancer cells are resistant to these drugs have emerged as some of the most challenging properties of cancer to overcome. Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stemness (CS) are known to be pivotal for driving metastasis, recurrence, and resistance for treatment in lung cancer, but the nature of these factors is not completely understood.

EMT is a critical event not only in embryonic development and in cell migration during wound healing or tissue development 3, 4, but also in the migration of malignant cells undergoing invasion and metastasis 4, 5, 6. EMT is composed of two processes: the loss of epithelial characters and the gain of mesenchymal characters 4, 7. E‐cadherin is the membrane protein working as an adhesion molecule, and it is the most common epithelial factor. The loss of E‐cadherin is one of the major features of EMT 4. In contrast, N‐Cadherin 8, SNAIL 4, 9, TWIST 10, and vimentin 4, 5, 11, 12 are mesenchymal factors that work during various phases of EMT. Vimentin, a member of the intermediate filament family, is the protein responsible for maintaining cellular integrity and reducing damage caused by stress. Vimentin is expressed in normal mesenchymal cells, and recent studies have shown a correlation between increased levels of vimentin expression and malignant progression in various types of cancers, such as prostate, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, breast, malignant melanoma, and lung cancers 12.

On the other hand, the cancer stem cell was first reported in 1997 by Bonnet, in human acute myeloid leukemia 13. The presence of cancer stem cells in solid tumors, such as breast cancer 14, colon cancer 15, pancreatic cancer 16, and brain tumors 17, has been proposed recently. Cancer stem cells are also called cancer‐initiating cells because of their capacities for self‐renewal, multi‐lineage differentiation, and higher levels of malignancy 18, 19. Some studies have shown that cancer stem cells are resistant to therapy and are responsible for tumor recurrence and metastasis 20. There are many reports in which CS markers correlated with patients' prognoses. Previous reports demonstrated that CD133 expression is correlated with brain 21 and colon cancer 22, CD44 is correlated with pancreatic cancer 23, and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is correlated with ovarian cancers 24. Some reports mentioned the presence of CS markers in lung cancer 25, 26, 27, but they are not definitive yet.

Previously, EMT and CS have been separately reported in terms of their unfavorable effects on prognosis. In in vitro experiments, the associations among each property have been reported 28, whereas their mutual associations in a clinical setting remain elusive.

The purposes of our present study are to elucidate the association between the EMT and CS and to determine their effect on the prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. We also present the key factors that link EMT and CS and discuss how these factors affect tumor malignancy in this study.

Methods

Patient selection

A total of 239 specimens of lung adenocarcinomas were collected from patients who had undergone surgery at the Kyoto University Hospital from January 2001 to December 2007. Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, underwent incurable surgery, or had multiple cancers, were excluded. All specimens were subjected to tissue microarray (TMA) analysis, as described below. The tumors were staged according to the 7th edition of the TNM classification of the International Union Against Cancer 29. Histological classification was according to the 2004 WHO classification 30 and the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma 31. According to the IASLC/ATS/ERS criteria, each tumor was reviewed using comprehensive histologic subtyping and the percentage of each histologic component in 5% increments was recorded. The survival time and outcome data were available for all 239 patients, with a median follow‐up time of 63.0 months (range: 1–129 months). Approval for the use of the tissues in this research was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto University.

Tissue microarray

TMAs were made by the pathologists in the department of Diagnostic Pathology in Kyoto University Hospital 32 using a similar approach to that described previously by Kononen et al. 33. Briefly, after the case selection described above, paraffin‐embedded tumor blocks with sufficient tissue were selected for TMA. The most representative regions of the tumors were selected based on the morphology of the H&E‐stained slide. Tissue cores measuring 2 mm in diameter were punched out from each donor tumor block, using thin‐walled stainless steel needles (Azumaya Medical Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and were arrayed in a recipient paraffin block. Non‐neoplastic lung tissue cores from selected patients were also arrayed in the same block to serve as negative controls.

Immunohistochemical analysis

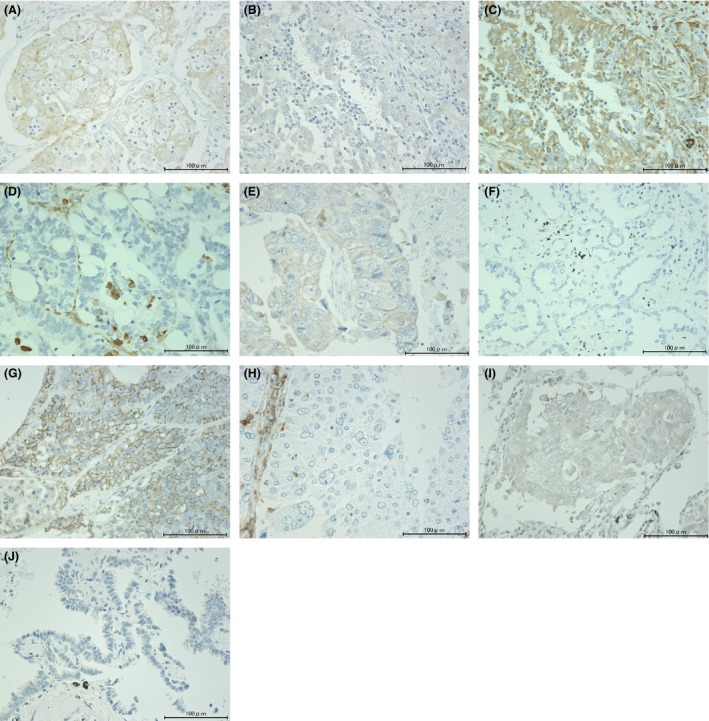

A standard immunostaining technique, which was previously published 34, was implemented in this study. Immunostaining against E‐cadherin, vimentin, CD133, CD44, and ALDH was performed with mouse anti‐human E‐cadherin monoclonal antibody (36B5, dilution 1:300, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK), mouse anti‐human vimentin monoclonal antibody (SRL33, dilution 1:300, Leica Biosystems), mouse anti‐human CD133 monoclonal antibody (W6B3C1, dilution 1:10, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), mouse anti‐human CD44 monoclonal antibody (156‐3C11, dilution 1:50; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and rabbit anti‐human ALDH1A1 polyclonal antibody (dilution at 1:3000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After deparaffinization and rehydration, the slides were heated in a microwave for 20 min in 10 μmol/L citrate buffer solution at pH 6.0 (E‐cadherin, vimentin, CD133, CD44), or heated by autoclaving for 5 min (ALDH). After quenching the endogenous peroxidase activity with 0.3% H2O2 in absolute methanol for 30 min, the sections were treated with 1% horse (E‐cadherin, vimentin, CD133, CD44) or goat (ALDH) normal serum albumin. The sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies. Slides were then incubated for 1 h with each equivalent biotinylated secondary antibody. The sections were incubated with the avidin–peroxidase complex for 1 h and visualized with 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dojindo laboratories, Kumamto, Japan). Lastly, the sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. The immunostained sections were examined by two authors (T. S. and T. M.) without knowledge of the patient characteristics. Cases with discrepancies were jointly reevaluated until a consensus was reached. After immunostaining, the expressions of these proteins were examined in four distinct fields with a minimum of 500 cells. The proportion of positive cells was measured and classified as 0 (no staining), +1 (weak), +2 (moderate), and +3 (strong), and each specimen was categorized as negative (0, +1) or positive (+2, +3). Figure 1 shows representative images of immunohistochemical staining by anti E‐cadherin (A, B), vimentin (C, D), CD133 (E, F), CD44 (G, H), and ALDH (I, J) antibodies.

Figure 1.

Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of lung adenocarcinoma sections with anti‐E‐cadherin (A and B), vimentin (C and D), CD133 (E and F), CD44 (G and H), and ALDH (I and J) antibodies. (A, C, E, G, and I) show positive expression, while B, D, F, H, and J show negative expression. (Original magnification, ×400). ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Statistical analysis

Age and average smoking index were summarized using the mean ± SD, whereas the categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages. The OS (overall survival) was calculated from the date of surgery. Time‐to‐event curves for OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in time‐to‐event curves were evaluated with the log‐rank test. The correlations among the five markers were analyzed using odds ratio and chi‐square tests. The analysis of the hazard ratio was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. All P‐values were two‐sided and P‐values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients and tumors evaluated in our study are summarized in Table 1. There were 123 (51.5%) men, with a mean age of 67.0 ± 9.6 years (range, 23–86 years). One hundred and nine patients (45.6%) had never smoked, and 130 patients (54.3%) were former or current smokers, with an average smoking index of 26.5 ± 36.4 pack‐years. The numbers of patients at each pathological stage were as follows: IA, 119 (49.8%); IB, 70 (29.3%); IIA, 22 (9.2%); IIB, 4 (1.7%); IIIA, 23 (9.6%) patients; and IIIB, 1 (0.4%) (Table 1). There were 189 (79.1%) pathological stage I cases in this study, which is higher than that generally reported. The frequency of EMT or CS marker expressions is shown in Table 2. The analysis of TMA specimens for EMT and CS markers indicated that of the 239 cases, 120 (50.2%) specimens were positive for E‐cadherin, 50 (20.9%) for vimentin, 26 (10.9%) for CD133, 48 (20.1%) for CD44, and 89 (37.2%) for ALDH, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients included in this study

| Variables | N = 239 |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 123 (51.5) |

| Female | 116 (48.5) |

| Age (years), 67.0 ± 9.6 years old | |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 109 (45.6%) |

| Former/current | 130 (54.3%) |

| Average smoking index | 26.5 ± 36.4 pack‐years |

| p‐Stage (%) | |

| IA | 119 (49.8) |

| IB | 70 (29.3) |

| IIA | 22 (9.2) |

| IIB | 4 (1.7) |

| IIIA | 23 (9.6) |

| IIIB | 1 (0.4) |

| Tumor grade (%) | |

| Well differentiated | 47 (19.7) |

| Moderately differentiated | 97 (40.6) |

| Poorly differentiated | 95 (39.8) |

| Lymphatic invasion (%) | |

| Absent | 193 (80.8) |

| Present | 46 (19.3) |

| Vascular invasion (%) | |

| Absent | 184 (77.0) |

| Present | 55 (23.0) |

| Pleural invasion (%) | |

| pl 0 | 188 (78.7) |

| pl 1‐3 | 51 (21.3) |

| IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma in situ | 9 (3.8) |

| Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma | 13 (5.4) |

| Lepidic predominant | 18 (7.5) |

| Acinar predominant | 31 (13.0) |

| Papillary predominant | 111 (46.4) |

| Micropapillary predominant | 8 (3.4) |

| Solid predominant | 41 (17.2) |

| Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma | 7 (2.9) |

| Others | 1 (0.4) |

Table 2.

Expressions of EMT and CS markers in the specimens

| E‐cadherin | Vimentin | CD133 | CD44 | ALDH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 120 (50.2%) | 50 (20.9%) | 26 (10.9%) | 48 (20.1%) | 89 (37.2%) |

| Negative | 119 (49.8%) | 189 (79.1%) | 213 (89.1%) | 191 (79.9%) | 149 (62.3%) |

One specimen could not be evaluated for its ALDH expression, because the specimen was insufficient in the tissue microarray slide. EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition; CS, cancer stemness; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Relationship between EMT markers and patient prognosis

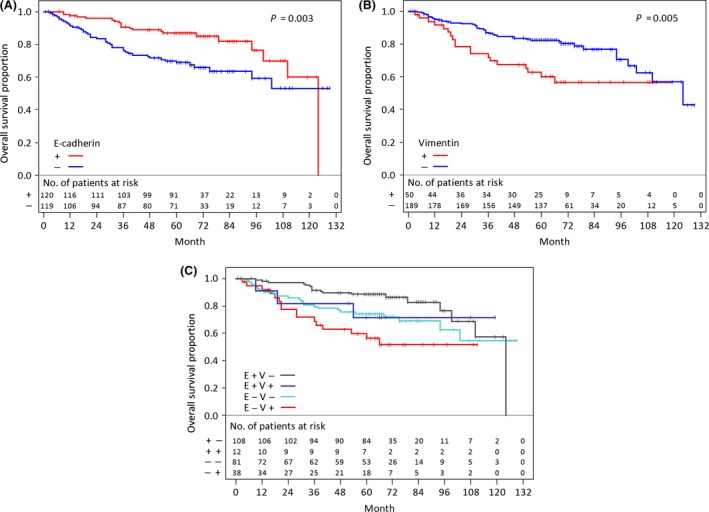

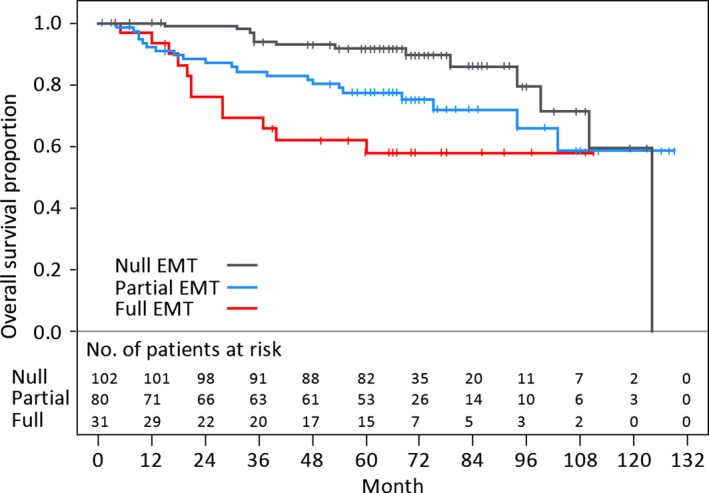

The prognoses of patients depending on EMT markers are shown in Figures 2A and B. The negative E‐cadherin group and the positive vimentin group had significantly poorer prognoses (Fig. 2A and B, P = 0.003 and P = 0.005, respectively). The prognoses of patients depending on the combination of EMT markers are shown in Figure 2C. These data suggest that the null EMT conversion group (positive E‐cadherin and negative vimentin) had the best prognosis, and that patients with EMT progression indicated a worse prognosis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival and log‐rank P values according to EMT markers. (A) E‐cadherin, (B) vimentin, and (C) combination of EMT markers. (E+) E‐cadherin positive, (E−) E‐cadherin negative, (V+) vimentin positive, and (V−) vimentin negative, EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition.

Relationship between CS markers and patient prognosis

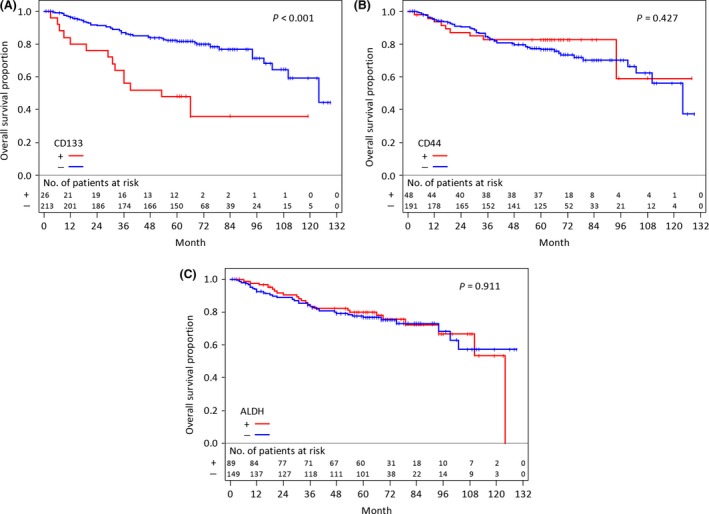

The prognoses affected by CS markers are shown in Figure 3A, B, and C. The expression of CD133 had a significantly unfavorable effect on prognosis (Fig. 3A, P < 0.001). However, the expression of CD44 and ALDH did not significantly correlate with the prognosis of the patients (Fig. 3B and C, P = 0.427 and P = 0.911, respectively). In our study, CD133 is the only prognostic factor of CS among these markers.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival and log‐rank P values according to CS markers. (A) CD133, (B) CD44, and (C) ALDH. ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; CS, cancer stemness.

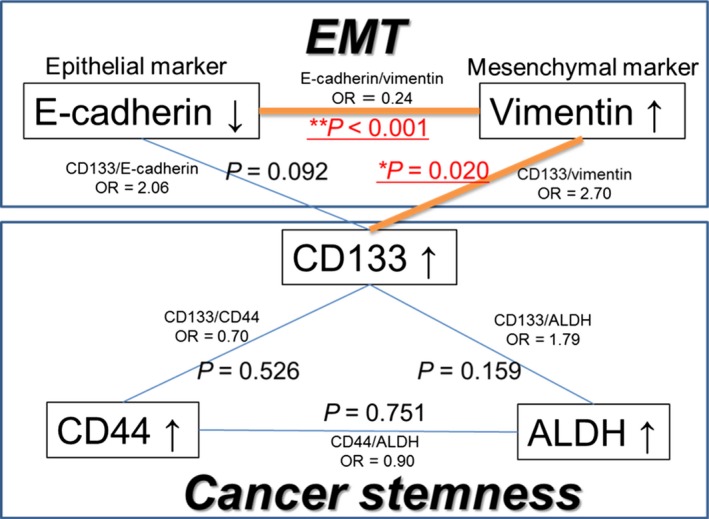

Association among EMT and CS markers in lung adenocarcinoma

The association between EMT and CS markers is shown in Figure 4. A negative correlation was found between E‐cadherin and vimentin expression (P < 0.001), whereas, a positive correlation was found between vimentin and CD133 expression (P = 0.020). Only CD133 was significantly correlated with EMT markers rather than the other CS markers.

Figure 4.

Association among EMT and CS markers. EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition; CS, cancer stemness; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; OR, odds ratio.

The expressions of the EMT marker vimentin and the CS marker CD133 showed significant correlation, suggesting that these factors are the key factors linking EMT and CS.

Effects of EMT and CS markers on patient prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma in multivariate analysis

We analyzed the effects of the expressions of CD133 and EMT markers on OS. Because CD133 was the strongest prognostic marker, as shown in Figure 3A, we divided the patients into positive or negative CD133 groups. In the positive CD133 group, there were no clear differences in the Kaplan–Meier curves for OS among the subgroups with EMT progression. Since only 26 patients were included in this group, we combined them into one group for an additional analysis (Table 3, CD133+). Regarding the negative CD133 group, we classified this group into three groups, based on the expression of E‐cadherin and vimentin, as follows: full EMT conversion group, E‐cadherin‐negative and vimentin‐positive; partial EMT conversion group, both E‐cadherin‐ and vimentin‐negative or positive; and null EMT conversion group, E‐cadherin‐positive and vimentin‐negative.

Table 3.

The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for EMT and CS markers (adjustment factors: p‐stage, sex, age)

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD133+ | 3.56 | [1.62–7.81] | 0.002 |

| CD133− & Full EMT | 1.90 | [0.83–4.32] | 0.127 |

| CD133− & Partial EMT | 2.07 | [1.04–4.24] | 0.038 |

| CD133− & Null EMT (Reference) | 1 | ||

| p‐stage [II, III/I] | 6.38 | [3.61–11.4] | <0.001 |

| Sex [male/female] | 1.58 | [0.92–2.80] | 0.099 |

| Age | 1.03 | [1.00–1.06] | 0.073 |

The hazard ratios of groups stratified by CD133 expression and EMT progression are shown in Table 3. Since only 26 patients were included in the CD133 positive group, we combined them into one group for this analysis (CD133+). These hazard ratios are standardized with that of the CD133− and null EMT conversion group. CI, confidence interval; EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition; CS, cancer stemness.

In Figure 5, there were clear differences in the Kaplan–Meier curves for OS among the negative CD133 groups divided by the progression of EMT. The group indicating negative CD133 and null EMT conversion showed the best prognosis.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival of the groups of CD133‐negative patients divided by the progression of EMT. Three groups of CD133‐negative patients are shown based on the expression of E‐cadherin and vimentin as follows; full EMT conversion group, E‐cadherin‐negative and vimentin‐positive; partial EMT conversion group, both E‐cadherin‐ and vimentin‐negative or positive; null EMT conversion group, E‐cadherin‐positive and vimentin‐negative. EMT, epithelial‐mesenchymal transition.

Table 3 shows the results of a Cox regression analysis adjusted for covariates (p‐stage, sex, and age). As compared with the negative CD133 and null EMT conversion group, the hazard ratios (P‐values) of the positive CD133 group, negative CD133 and full EMT conversion group, and negative CD133 and partial EMT conversion group were 3.56 (P = 0.002), 1.90 (P = 0.127), and 2.07 (P = 0.038), respectively. The positive CD133 group showed the worst prognosis (P = 0.002).

Discussion

Importantly, our research shows the effects of EMT and CS on patients' prognoses and a clear association between EMT and CS in clinical specimens. The EMT marker vimentin and CS marker CD133 will be focused on as the key factors linking EMT with CS.

EMT and CS have been reported to affect migration, invasion, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance 4, 6, 20. Surprisingly, there are few reports referring to the association of EMT and CS. In an in vitro study, Mani et al. reported that EMT‐induced normal epithelial mammary cells obtained the characteristics of CS including CD133 expression 28. Pirozzi et al. also reported that the EMT‐induced cancer cell line A549 acquired CS 35. In clinical reports, there have been many articles about each marker, but the associations between EMT and CS have not been reported previously. Our study revealed that vimentin and CD133 expression are correlated, and that the CS marker CD133 is associated with a worse prognosis than EMT conversion.

However, it remains unclear how vimentin and CD133 affected the prognoses in our report. CD133 is a five‐transmembrane cell surface glycoprotein family, and its gene, PROM1 is specifically located on chromosome 4p15, a region that contains genes related to mature organ homoeostasis, tumorigenesis, and cancer progression 36. Previous studies have determined that positive CD133 cancer cells possess CS 36, but its precise function remains unclear. Tirino et al. investigated the role of CD133 by analyzing the differences between positive and negative CD133 subpopulations in the lung cancer cell line A549 37. The positive CD133 subpopulation expressed vimentin more strongly and had more potential for invasion, migration, and distant metastasis than the negative CD133 one. These data are compatible with our results; that is, there is correlation between the expression of CD133 and vimentin, and the group with positive CD133 expression had a worse prognosis. Although the major roles of CD133 remain unidentified, we have shown that CD133 has an important role in tumor progression in lung adenocarcinoma.

EMT progression was not an independent prognostic marker in our multivariate analysis (Table 3). EMT progression (full/partial/null) was significantly correlated with pathological stage (stage I/II, III) in our study (data not shown). This fact might have some effects on this result. Conversely, it is suggested that EMT correlates with T or N factors, which is very interesting.

Cancer, including lung adenocarcinoma, has been difficult to treat. The characteristics of the EMT and CS have been widely investigated, but EMT and CS have not been examined enough as therapeutic targets. Since the expressions of vimentin and CD133 are correlated, targeting CS via EMT may be possible. For example, silibinin was reported to inhibit tumor progression via vimentin and MMP‐2 suppression 38, 39, and salinomycin was reported to lead to the regression of cancer via the suppression of the EMT and CS marker, CD133 40. Our study supports these previous reports and shows the possibility of their application for clinical therapy.

It is necessary to understand the common background mechanisms underlying EMT and CS. The reports that transforming growth factor beta‐induced EMT and CS in an in vitro study 28, 35 suggest the probability that the tumor microenvironment including cancer–associated fibroblasts influence the EMT and CS. In addition, hypoxia is also reported to induce EMT and CS via the upregulation of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1α expression 41, 42. These mechanisms may underlie the results of the present study. Interventions targeting these factors will be necessary for the innovative therapy of lung cancer. Moreover, the associations of EMT or CS with pathological characteristics or genetic alternations are not definitive in lung cancer 43, 44. The analyses of these factors are now underway in our group, and they will also be useful to unveil the nature of EMT and CS.

There are some limitations to our study. First, the proportion of stage I cases in our study is 79.1%, and it is larger than what has generally been reported 45. This is because patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy, undergoing incurable surgery, and those with multiple cancers were excluded to ensure accurate evaluation of the association between these biomarkers and prognoses. It is possible that this fact had some effect on our results. Second, the expression of CD44 was detected using a mouse anti‐human CD44 monoclonal antibody (pan‐CD44), and it was not prognostic in our study. Regarding CD44, both pan‐CD44 and its variant CD44v6 were reported to be prognostic 26. It is not yet definitive which splice variant is more prognostic, and further investigation will be needed.

In conclusion, we showed that the progression of EMT and the expression of the CS marker CD133 had significantly unfavorable effects on the prognoses of lung adenocarcinoma patients. The EMT and CS were significantly correlated through vimentin and CD133. The CS marker CD133 was a stronger prognostic factor than the EMT markers. Further research into these factors is expected to elucidate how cancers acquire metastatic potency and resistance against treatments associated with the EMT and CS.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Cancer Medicine 2015; 4(12): 1853–1862

References

- 1. Torre, L. A. , Bray F., Siegel R. L., Ferlay J., Lortet‐Tieulent J., and Jemal A.. 2015. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65:95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devesa, S. S. , Bray F., Vizcaino A. P., and Parkin D. M.. 2005. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male:female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. Int. J. Cancer 117:294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenburg, G. , and Hay E. D.. 1982. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J. Cell Biol. 95:333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kalluri, R. , and Weinberg R. A.. 2009. The basics of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1420–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ivaska, J. 2011. Vimentin: central hub in EMT induction? Small GTPases 2:51–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thiery, J. P. 2002. Epithelial‐mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:442–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franke, W. W. , Schmid E., Osborn M., and Weber K.. 1978. Different intermediate‐sized filaments distinguished by immunofluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:5034–5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Derycke, L. D. , and Bracke M. E.. 2004. N‐cadherin in the spotlight of cell‐cell adhesion, differentiation, embryogenesis, invasion and signalling. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48:463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nieto, M. A. 2002. The snail superfamily of zinc‐finger transcription factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang, J. , Mani S. A., Donaher J. L., Ramaswamy S., Itzykson R. A., Come C., et al. 2004. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell 117:927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vuoriluoto, K. , Haugen H., Kiviluoto S., Mpindi J. P., Nevo J., Gjerdrum C., et al. 2011. Vimentin regulates EMT induction by Slug and oncogenic H‐Ras and migration by governing Axl expression in breast cancer. Oncogene 30:1436–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Satelli, A. , and Li S.. 2011. Vimentin in cancer and its potential as a molecular target for cancer therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68:3033–3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonnet, D. , and Dick J. E.. 1997. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 3:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al‐Hajj, M. , Wicha M. S., Benito‐Hernandez A., Morrison S. J., and Clarke M. F.. 2003. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3983–3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ricci‐Vitiani, L. , Lombardi D. G., Pilozzi E., Biffoni M., Todaro M., Peschle C., et al. 2007. Identification and expansion of human colon‐cancer‐initiating cells. Nature 445:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li, C. , Heidt D. G., Dalerba P., Burant C. F., Zhang L., Adsay V., et al. 2007. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 67:1030–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh, S. K. , Clarke I. D., Terasaki M., Bonn V. E., Hawkins C., Squire J., et al. 2003. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lobo, N. A. , Shimono Y., Qian D., and Clarke M. F.. 2007. The biology of cancer stem cells. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:675–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rapp, U. R. , Ceteci F., and Schreck R.. 2008. Oncogene‐induced plasticity and cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle 7:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Monteiro, J. , and Fodde R.. 2010. Cancer stemness and metastasis: therapeutic consequences and perspectives. Eur. J. Cancer 46:1198–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shibahara, I. , Sonoda Y., Saito R., Kanamori M., Yamashita Y., Kumabe T., et al. 2013. The expression status of CD133 is associated with the pattern and timing of primary glioblastoma recurrence. Neuro. Oncol. 15:1151–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Artells, R. , Moreno I., Diaz T., Martinez F., Gel B., Navarro A., et al. 2010. Tumour CD133 mRNA expression and clinical outcome in surgically resected colorectal cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 46:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ohara, Y. , Oda T., Sugano M., Hashimoto S., Enomoto T., Yamada K., et al. 2013. Histological and prognostic importance of CD44(+)/CD24(+)/EpCAM(+) expression in clinical pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 104:1127–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silva, I. A. , Bai S., McLean K., Yang K., Griffith K., Thomas D., et al. 2011. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in combination with CD133 defines angiogenic ovarian cancer stem cells that portend poor patient survival. Cancer Res. 71:3991–4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alamgeer, M. , Ganju V., Szczepny A., Russell P. A., Prodanovic Z., Kumar B., et al. 2013. The prognostic significance of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1) and CD133 expression in early stage non‐small cell lung cancer. Thorax 68:1095–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo, Z. , Wu R. R., Lv L., Li P., Zhang L. Y., Hao Q. L., et al. 2014. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in non‐small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7:3632–3646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu, H. , Qi X. W., Yan G. N., Zhang Q. B., Xu C., and Bian X. W.. 2014. Is CD133 expression a prognostic biomarker of non‐small‐cell lung cancer? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE 9:e100168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mani, S. A. , Guo W., Liao M. J., Eaton E. N., Ayyanan A., Zhou A. Y., et al. 2008. The epithelial‐mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133:704–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sobin, L. H. G. M. , and Wittekind C.. 2009. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed John Wiley & Sons, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Travis, W. D. , Brambilla E., Muller‐Hermelink H. K., and Harris C. C.. 2004. Pathology & Genetics Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. France, Lyon: IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Travis, W. D. , Brambilla E., Noguchi M., Nicholson A. G., Geisinger K. R., Yatabe Y., et al. 2011. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6:244–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoshizawa, A. , Sumiyoshi S., Sonobe M., Kobayashi M., Uehara T., Fujimoto M., et al. 2014. HER2 status in lung adenocarcinoma: a comparison of immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), dual‐ISH, and gene mutations. Lung Cancer 85:373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kononen, J. , Bubendorf L., Kallioniemi A., Barlund M., Schraml P., Leighton S., et al. 1998. Tissue microarrays for high‐throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat. Med. 4:844–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Toda, Y. , Kono K., Abiru H., Kokuryo K., Endo M., Yaegashi H., et al. 1999. Application of tyramide signal amplification system to immunohistochemistry: a potent method to localize antigens that are not detectable by ordinary method. Pathol. Int. 49:479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pirozzi, G. , Tirino V., Camerlingo R., Franco R. La, Rocca A., Liguori E., et al. 2011. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition by TGFbeta‐1 induction increases stemness characteristics in primary non small cell lung cancer cell line. PLoS ONE 6:e21548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yin, A. H. , Miraglia S., Zanjani E. D., Almeida‐Porada G., Ogawa M., Leary A. G., et al. 1997. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 90:5002–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tirino, V. , Camerlingo R., Bifulco K., Irollo E., Montella R., Paino F., et al. 2013. TGF‐beta1 exposure induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition both in CSCs and non‐CSCs of the A549 cell line, leading to an increase of migration ability in the CD133+ A549 cell fraction. Cell Death Dis. 4:e620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cufi, S. , Bonavia R., Vazquez‐Martin A., Oliveras‐Ferraros C., Corominas‐Faja B., Cuyas E., et al. 2013. Silibinin suppresses EMT‐driven erlotinib resistance by reversing the high miR‐21/low miR‐200c signature in vivo. Sci. Rep. 3:2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singh, R. P. , Raina K., Sharma G., and Agarwal R.. 2008. Silibinin inhibits established prostate tumor growth, progression, invasion, and metastasis and suppresses tumor angiogenesis and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 14:7773–7780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dong, T. T. , Zhou H. M., Wang L. L., Feng B., Lv B., and Zheng M. H.. 2011. Salinomycin selectively targets ‘CD133+' cell subpopulations and decreases malignant traits in colorectal cancer lines. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 18:1797–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sahlgren, C. , Gustafsson M. V., Jin S., Poellinger L., and Lendahl U.. 2008. Notch signaling mediates hypoxia‐induced tumor cell migration and invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:6392–6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liang, D. , Ma Y., Liu J., Trope C. G., Holm R., Nesland J. M., et al. 2012. The hypoxic microenvironment upgrades stem‐like properties of ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer 12:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakagiri, T. , Sawabata N., Morii E., Inoue M., Shintani Y., Funaki S., et al. 2014. Evaluation of the new IASLC/ATS/ERS proposed classification of adenocarcinoma based on lepidic pattern in patients with pathological stage IA pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 62:671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sterlacci, W. , Savic S., Fiegl M., Obermann E., and Tzankov A.. 2014. Putative stem cell markers in non‐small‐cell lung cancer: a clinicopathologic characterization. J. Thorac. Oncol. 9:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goya, T. , Asamura H., Yoshimura H., Kato H., Shimokata K., Tsuchiya R., et al. 2005. Prognosis of 6644 resected non‐small cell lung cancers in Japan: a Japanese lung cancer registry study. Lung Cancer 50:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]