Abstract

The Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study began in June 2009 as combat operations were decreasing in Iraq and increasing in Afghanistan. Our analysis examines the rate of infections of wounded U.S military personnel from operational theaters in Iraq and Afghanistan admitted to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center between June 2009 and December 2013 and transferred to a participating U.S. hospital. Infection risk factors were examined in a multivariate logistic regression analysis (expressed as odds ratios [OR]; 95% confidence intervals [CI]). The study population includes 524 wounded military personnel from Iraq and 4766 from Afghanistan. The proportion of patients with at least one infection was 28% and 34% from the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters, respectively. The incidence density rate was 2.0 (per 100 person-days) for Iraq and 2.7 infections for Afghanistan. Independent risk factors included large-volume blood product transfusions (OR: 10.68; CI: 6.73–16.95), high injury severity score (OR: 2.48; CI: 1.81–3.41), and improvised explosive device injury mechanism (OR: 1.84; CI: 1.35–2.49). Operational theater (OR: 1.32; CI: 0.87–1.99) was not a risk factor. The difference in infection rates between operational theaters is primarily due to increased injury severity in Afghanistan from a higher proportion of blast-related trauma during the study period.

Keywords: Combat-related infections, injury severity, trauma-related infections, combat care, military medicine

INTRODUCTION

It is widely recognized that individuals with combat-related injuries are at high risk for infectious complications.1–4 Combat-related injuries result in circumstances, such as breach of physical host defences, hypoxic tissue damage/necrosis, and implantation of foreign bodies, which greatly increase the risk of infection. The nature of trauma inflicted during combat (e.g., blast injuries) is generally more severe than injuries acquired in civilian settings.5–7

Since U.S. military personnel were first deployed to Iraq (Operations Iraqi Freedom [OIF] and New Dawn [OND] and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF]), over 52,100 service members have been wounded in action.8 These military operations saw changes in the patterns and severity of combat-related injuries, primarily due to the expanded utilization of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).2–4,9–11 Accordingly, combat care evolved through advancements in preventive measures and treatments, along with the implementation of the Joint Theater Trauma System (JTTS) in November 2004.12,13 In part due to the integrated approach to combat care executed by the JTTS, which emulates successful civilian trauma systems, the overall mortality rate of military personnel decreased during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (8.8%) when compared to World War II and Vietnam (22.8% and 16.5%, respectively).12 Nonetheless, the improved survival of wounded military personnel resulted in a rise of infectious complications and consequent effects on morbidity.2–4,14–17

In order to better characterize these infections, an observational cohort study of short- and long-term infectious consequences among U.S. service members injured during deployment (Department of Defense [DoD]-Department of Veterans Affairs, Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study [TIDOS]) was initiated in 2009. An examination of data collected from the project reported an overall infection incidence density of 1.8 per 100 person-days among wounded U.S. military personnel medically evacuated to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) in Germany and transitioned to participating military treatment facilities (MTFs) in the U.S. between June and August 2009. In the analysis, infection rates were assessed with regards to level of care (LRMC and U.S. MTFs) and admitting units (intensive care versus non-critical ward); however, operational theater where the injury was sustained was not examined.3 For military personnel with injuries sustained during the recent conflicts, the risk of infection may differ between operational theaters due to diversities in injury mechanism (e.g., gunshot and blast wounds), environment (i.e., arid/urban landscape in Iraq versus the mountainous and agricultural settings in Afghanistan), or infectious exposures. Our objective was to assess infection rates among U.S. military personnel injured during deployment (combat and noncombat) with respect to operational theater (Iraq and Afghanistan).

METHODS

Study Design

The TIDOS project is a multisite, observational cohort study initiated with the goal of describing the incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes of infectious complications associated with deployment-related injuries. The study commenced during a period when combat operations were decreasing in Iraq while simultaneously increasing in Afghanistan. Full details regarding the TIDOS project design have been previously published.3 Eligible subjects include U.S. service members injured during deployment (June 1, 2009 to January 31, 2015) and medically evacuated to LRMC followed by transition to a participating U.S. MTF. This study (IDCRP-024) is approved by the Infectious Disease Institutional Review Board of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland.

Data Collection

Trauma information (e.g., injury patterns and severity) were obtained through the DoD Trauma Registry (DoDTR).12 The TIDOS infectious disease module augmented the DoDTR data by providing detailed information on antimicrobial therapy, microbiology, and infectious outcomes from injury through initial hospitalization at a participating U.S. MTF: National Naval Medical Center and Walter Reed Army Medical Center in the National Capital Region (Walter Reed National Military Medical Center after September 2011), and Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas (San Antonio Military Medical Center after September 2011).

Study Definitions and Endpoints

Traumatic injuries sustained during deployment were categorized using injury codes defined by the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), a consensus-derived anatomically-based injury scoring system.18 A composite injury severity score (ISS) was calculated for each patient based on the top three maximum AIS anatomical region values across all clinical facilities. Combat-related injuries were identified as traumatic injuries occurring within the operational theater that include the following injury mechanisms: blast, gunshot wound, motor vehicle/helicopter crash, fall/crush, and burns. Noncombat injuries, including sports and training injuries, were sustained while deployed and may include similar mechanisms (i.e., falls/crush, burns, and motor vehicle crashes), but were not directly related to combat operations.

As described in Tribble et al.,3 infections were identified utilizing a combination of clinical findings and laboratory test results via review of medical records and were classified based upon the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) standardized definitions for healthcare-associated infections.19 Furthermore, an infection was included if, in the absence of meeting a priori defined criteria, there was a clinical diagnosis associated with the initiation of directed antimicrobial therapy that was continued for more than five days. Infections were excluded from the analysis if medical records provided an alternative diagnosis combined with the termination of antimicrobial treatment. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates were identified in accordance with definitions published by the NHSN.20 Isolates were classified as colonizing if they were collected via infection control-based surveillance. Isolates were considered infecting if they were collected as part of a clinical infection work-up and met infection clinical syndrome criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Tests of association for categorical variables were conducted using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, while medians were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Logistic regression models were used to assess the relationship between potential risk factors and outcomes (presence or absence of infection). The risk factor analysis was restricted to data collected from patients who transferred to participating U.S. MTFs. For each of the variables, the best-fitting parsimonious model was sought. A correlation analysis was also conducted to evaluate the relationship between potential risk factors. Models were compared on the basis of the Akaike Information Criterion and Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit. Analysis was conducted with SAS® version 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC). Data are expressed as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Study Population and Injury Patterns

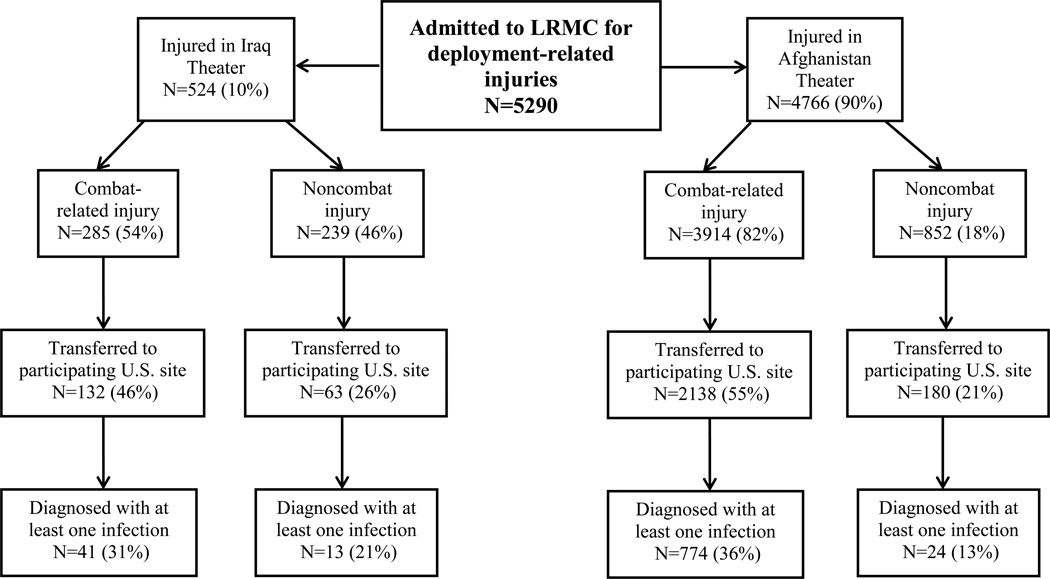

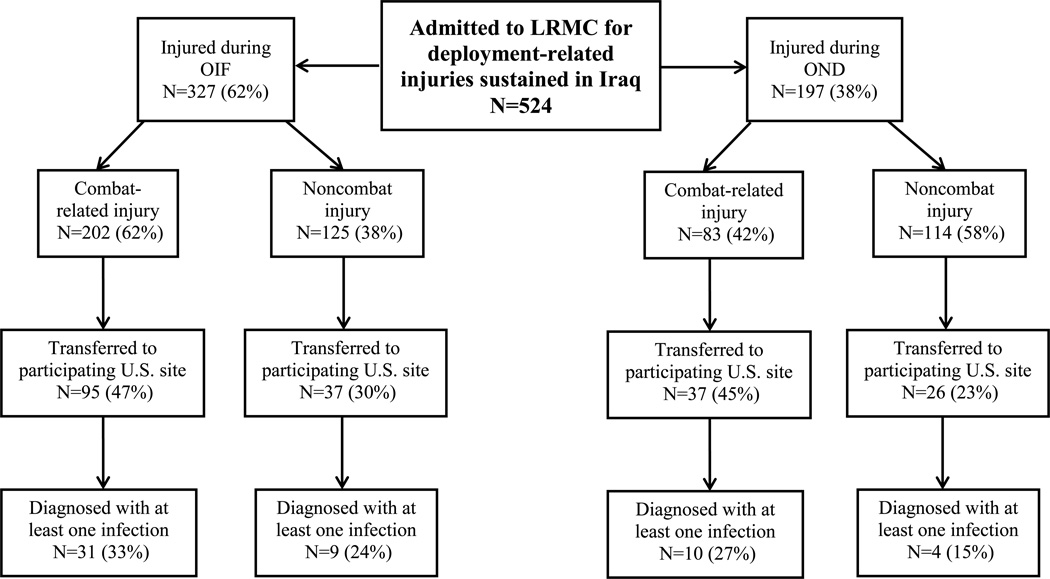

A total of 5290 wounded military personnel were admitted to LRMC between June 2009 and December 2013 (Figure 1), of which 4766 sustained injuries in Afghanistan (82% combat-related) and 524 in Iraq (54% combat-related). As previously mentioned, the start of the study period coincided with declining combat operations in Iraq (OIF ended on August 31, 2010 and peacekeeping support with OND began on September 1, 2010), while operations increased in Afghanistan. Specifically, 327 and 197 were wounded in support of OIF (62% combat-related) and OND (42% combat-related), respectively (Figure 2). For both theaters, the population was predominantly young enlisted men (>90%) serving in the U.S. Army (83% and 67%, respectively) or U.S. Marines (4% and 25%, respectively; Table 1). Furthermore, 52% and 72% of combat casualties sustained a blast injury in the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters, respectively, of which 67% and 78%, respectively, were the result of an IED. In addition, 14% of military personnel in Iraq and 33% in Afghanistan were injured while on foot patrol. The predominant injury mechanisms among personnel with noncombat trauma were falls (31% and 32% for Iraq and Afghanistan theaters, respectively) and sports-related injuries (21% and 15%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for disposition of patients admitted to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) between June 2009 and December 2013 with deployment-related injuries.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for disposition of patients admitted to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center with deployment-related injuries sustained in the Iraq theater. Combat operations in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF]) ended on August 31, 2010 and were followed by peacekeeping efforts (Operation New Dawn [OND]) which began on September 1, 2010 and ended on December 31, 2011.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Injury Characteristics, No. (%) by Theater of Operation (June 2009 – December 2013)

| Characteristic1 | Total (N = 5290) |

Afghanistan (N = 4766) |

Iraq (N = 524) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Noncombat Injury (N=852) |

Combat- related Injury (N=3914) |

p-value2 |

Noncombat Injury (N=239) |

Combat-related Injury (N=285) |

p-value3 | ||

| Male | 5160 (97.5) | 813 (95.4) | 3853 (98.4) | <0.0001 | 223 (93.3) | 271 (95.0) | 0.382 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 24.9 (22.1, 29.6) | 26.4 (22.6, 34.4) | 24.4 (22.0, 28.3) | <0.0001 | 28.1 (22.8, 35.8) | 25.7 (22.6, 30.8) | 0.012 |

| Branch of Service | <0.001 | 0.031 | |||||

| Army | 3608 (68.2) | 552 (64.7) | 2619 (66.9) | 187 (78.2) | 250 (87.7) | ||

| Marine | 1206 (22.7) | 151 (17.7) | 1034 (26.4) | 14 (5.8) | 7 (2.4) | ||

| Military Grade/Rank | 0.003 | 0.462 | |||||

| Enlisted | 4790 (90.5) | 747 (87.6) | 3573 (91.2) | 213 (89.1) | 257 (90.1) | ||

| Officer / Warrant | 379 (7.2) | 80 (9.4) | 256 (6.5) | 22 (9.2) | 21 (7.4) | ||

| Mechanism of Injury | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Blast | 2912 (55.0) | 0 | 2764 (70.6) | <0.0001 | 0 | 148 (51.9) | <0.0001 |

| IED | 2262 (42.8) | 0 | 2163 (55.3) | 0 | 99 (34.7) | ||

| Non-IED | 650 (12.3) | 0 | 601 (15.4) | 0 | 49 (17.2) | ||

| Gunshot wound only | 965 (18.2) | 0 | 918 (23.5) | 0 | 47 (16.5) | ||

| Motor vehicle collision only | 195 (3.7) | 10 (1.2) | 110 (2.8) | 6 (2.5) | 69 (24.2) | ||

| Helicopter crash | 35 (0.7) | 0 | 30 (0.8) | 0 | 5 (1.8) | ||

| Blunt object | 118 (2.2) | 79 (9.3) | 3 (<0.1) | 33 (13.8) | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Fall | 384 (7.3) | 273 (32.0) | 31 (0.8) | 74 (31.0) | 6 (2.1) | ||

| Sports | 180 (3.4) | 130 (15.3) | 0 | 50 (20.9) | 0 | ||

| Other4 | 499 (9.4) | 358 (42.0) | 58 (1.5) | 76 (31.8) | 7 (2.5) | ||

| Dismounted at time of injury | 1708 (32.3) | 283 (33.2) | 1299 (33.2) | <0.0001 | 85 (35.6) | 41 (14.4) | <0.0001 |

| Injury Severity Score, median (IQR) | 10 (5, 22) | 4 (4, 8) | 12 (6, 27) | <0.0001 | 4 (4, 8) | 10 (5, 21) | <0.0001 |

| RBC Transfusions: 1st 24 Hours | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0/missing units5 | 3927 (74.2) | 838 (98.3) | 2634 (67.2) | 237 (99.1) | 218 (76.4) | ||

| 1–9 units | 761 (14.3) | 11 (1.2) | 698 (17.8) | 2 (0.8) | 50 (17.5) | ||

| 10 – 20 units | 336 (6.3) | 2 (0.2) | 322 (8.2) | 0 | 12 (4.2) | ||

| >20 units | 266 (5.0) | 1 (0.1) | 260 (6.6) | 0 | 5 (1.7) | ||

| Occurrence of open injury | 3793 (71.7) | 233 (27.3) | 3281 (83.8) | <0.0001 | 61 (25.5) | 218 (76.4) | <0.0001 |

| ICU Admission6 | <0.0001 | 0.015 | |||||

| LRMC only | 361 (6.8) | 15 (1.8) | 313 (8.0) | 9 (3.8) | 24 (8.4) | ||

| U.S. MTFs ± LRMC | 965 (18.2) | 29 (3.4) | 879 (22.5) | 11 (4.6) | 46 (16.1) | ||

| Non-ICU | 1180 (22.3) | 135 (15.8) | 940 (24.0) | 43 (18.0) | 62 (21.8) | ||

| Prophylactic antimicrobial use within 48 hours of injury | 3248 (61.3) | 196 (23.0) | 2849 (72.7) | <0.0001 | 44 (18.4) | 159 (55.7) | <0.0001 |

ICU – intensive care unit; IED – improvised explosive device; IQR – Interquartile Range; LRMC – Landstuhl Regional Medical Center; MTFs – military treatment facilities; RBC – packed red blood cells plus whole blood

Data are missing for some of the variables (branch of service missing 47; military rank missing 75; mechanism of injury missing 2; ICU admittance missing 2784). The high amount of ICU admission missing is due to the transfer of approximately half of the patients to non-participating sites.

P-value compares the noncombat and combat-related injury data for Afghanistan. Missing values are not included in calculation.

P-value compares the noncombat and combat-related injury data for Iraq. Missing values are not included in calculation.

Other includes burns, machinery/equipment accidents, noncombat explosions, and crush injuries.

Missing RBC transfusion data are not randomly distributed. Patients with missing RBC data are characterized by lower injury severity scores and shock indices. In addition, the majority of patients with missing RBC data did not sustain a traumatic amputation and were not admitted to the LRMC ICU.

Admission to the ICU is recorded within the first week of care at each facility.

Combat-related injuries among personnel serving in the Afghanistan theater were more severe than noncombat trauma (Table 1), as indicated by the significantly higher ISS (median of 12 versus 4; p<0.0001) and greater proportion of admittance to the intensive care unit (ICU; 30% versus 5%; p<0.0001). The pattern of injury was also significantly different with a higher proportion of open injuries (skin/soft-tissue and fractures) sustained by combat casualties (84%; p<0.0001) compared to noncombat (27%). Furthermore, the proportion of wounded service members receiving massive transfusions of packed red blood cells plus whole blood (RBC; >10 units) within the first 24 hours was significantly higher among those with combat-related trauma compared to noncombat (15% versus 0.4%; p<0.0001). Lastly, significantly more patients with combat-related injuries were also prescribed prophylactic antibiotics for prevention of infections within 48 hours following injury (73% versus 23%; p<0.0001).

A similar pattern was observed among military personnel injured in the Iraq theater (Table 1). Specifically, military personnel with combat-related trauma had significantly higher ISS (median of 10 versus 4; p<0.0001), occurrence of open injuries (76% versus 26%; p<0.0001), proportion of patients admitted to the ICU (25% versus 8%; p=0.015), any amount of RBCs transfused within 24 hours (24% versus 0.8%; p<0.0001), and receipt of prophylactic antibiotics within 48 hours (56% versus 18%; p<0.0001).

Infection Characteristics

From the population of 2513 patients transferred to participating U.S. MTFs (Table 2), 852 patients (34%) developed at least one infection (94% from Afghanistan and 6% from Iraq). Of the 54 patients from Iraq with at least one infection, 40 sustained injuries in OIF (78% combat-related) and 14 in OND (71% combat-related). A total of 2003 and 103 unique infections were diagnosed from military personnel wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively, of which 99% and 80% were combat-related, respectively (Table 2). Comparison of the incidence density rate ratio found that there was a significantly higher proportion of combat-related infections compared to noncombat in the Afghanistan theater (p<0.0001), but not in the Iraq theater of operation (p=1.0).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Inpatient Infections among Wounded Military Personnel after Transfer to a United States Military Treatment Facility (2009 – 2013)1

| Afghanistan Theater | Iraq Theater | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Noncombat Injury (N=180) |

Combat-related Injury (N=2138) |

Total (N=2318) |

Noncombat Injury (N=63) |

Combat-related Injury (N=132) |

Total (N=195) |

|

| Total Days of Patient Observations, No. | 3138 | 71,410 | 74,548 | 1043 | 4131 | 5174 |

| Unique Infections, No. | 30 | 1973 | 2003 | 21 | 82 | 103 |

| Infections per 100 person-days, No. (95% CI) | 1.0 (0.6–1.4) | 2.8 (2.6–2.9) | 2.7 (2.6–2.8) | 2.0 (1.2–3.1) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) |

| Patients admitted initially to LRMC ICU2 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 3.7 (3.5–3.9) | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 4.1 (2.4–6.7) | 2.6 (2.1–3.3) | 2.8 (2.3–3.5) |

| Patients admitted initially to LRMC Ward2 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.8 (0.2–1.8) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) |

| Incidence density rate ratio (95% CI): Combat versus Noncombat3 | NA | NA | 2.9 (2.0–4.3) | NA | NA | 0.99 (0.6–1.7) |

| Incidence density rate ratio (95% CI): LRMC ICU versus Ward4 | 2.0 (0.9–4.6) | 5.1 (4.3–6.0) | 5.0 (4.3–5.9) | 5.4 (1.9–18.9) | 3.5 (1.8–7.3) | 3.7 (2.2–6.8) |

| Patients with ≥1 infection, No. (%) | 24 (13) | 774 (36) | 798 (34) | 13 (21) | 41 (31) | 54 (28) |

| Infections per patient, No. (%)5 | ||||||

| 1 event | 20 (83.3) | 339 (43.8) | 359 (45.0) | 6 (46.2) | 17 (41.5) | 23 (42.6) |

| 2 events | 3 (12.5) | 174 (22.5) | 177 (22.2) | 6 (46.2) | 14 (34.1) | 20 (37.0) |

| 3 events | 0 | 97 (12.5) | 97 (12.2) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (12.2) | 6 (11.1) |

| ≥ 4 events | 1 (4.2) | 164 (21.2) | 165 (20.7) | 0 | 5 (12.2) | 5 (9.3) |

| Level of care location for infection, No. (%)5 | ||||||

| LRMC only | 5 (20.8) | 84 (10.9) | 89 (11.2) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (16.7) |

| U.S. MTF only | 19 (79.2) | 536 (69.3) | 555 (69.5) | 7 (53.8) | 29 (70.7) | 36 (66.7) |

| Both LRMC and U.S. MTF | 0 | 154 (19.9) | 154 (19.3) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (16.7) |

| Type of Infection, No. (%)6 | ||||||

| Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTI) | 14 (46.7) | 918 (46.5) | 932 (46.5) | 5 (23.8) | 18 (22.0) | 23 (22.3) |

| Pneumonia | 7 (23.3) | 273 (13.8) | 280 (14.0) | 6 (28.6) | 17 (20.7) | 23 (22.3) |

| Bloodstream infection | 3 (10.0) | 276 (14.0) | 279 (13.9) | 4 (19.1) | 13 (15.9) | 17 (16.5) |

| Sepsis (excluding SIRS) | 0 | 86 (4.4) | 86 (4.3) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (2.9) |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 (6.7) | 121 (6.1) | 123 (6.1) | 0 | 17 (10.7) | 17 (16.5) |

CI – Confidence Interval; ICU – intensive care unit; LRMC – Landstuhl Regional Medical Center; MTF – military treatment facility; NA – Not applicable; SIRS – systemic inflammatory response system

Data are restricted to patients who transferred to a participating U.S. MTF following treatment at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center.

Total number of patients initially admitted to LRMC ICU was 1195 for Afghanistan (combat: 1152; noncombat: 43) and 88 for Iraq (combat: 69; noncombat: 19). Total number of patients initially admitted to LRMC ward was 1118 for Afghanistan (combat: 982; noncombat 136) and 107 for Iraq (combat: 63; noncombat: 44).

p-value for incidence density rate ratio of combat versus noncombat for Afghanistan and Iraq was <0.0001 and 1.0, respectively

p-value for incidence density rate ratio of LRMC ICU versus ward for Afghanistan was <0.0001 (combat: <0.0001; noncombat: 0.083) and for Iraq was <0.0001 (combat: <0.0001; noncombat: <0.001).

The total number of patients with ≥1 infection was used to calculate percent. P-values comparing the combat and noncombat data from Afghanistan and Iraq were 0.001 and 0.722 for infections per subject, respectively, and 0.010 and 0.448 for location of infection, respectively.

The total number of unique infections was used to calculate percent. Does not include miscellaneous infections, such as sinusitis, central nervous system infections, and urinary tract infections.

Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) and pneumonia were common for patients injured in both theaters regardless of whether they had combat-related or noncombat trauma (Table 2). Specifically, 47% of unique infections were SSTIs among both combat and noncombat trauma patients from Afghanistan, whereas pneumonia contributed 14% of infections among combat casualties and 23% among noncombat trauma patients. Regarding patients from Iraq, 22% and 24% of unique infections in combat and noncombat trauma patients were SSTIs, respectively, while it was 21% and 29% for pneumonia, respectively. Among those with an infection, most were diagnosed after transfer to a participating U.S. MTF (70% and 67% of patients from Afghanistan and Iraq theaters, respectively). In addition, the overall rate of infections was higher among patients initially admitted to the LRMC ICU compared to the noncritical ward for both theaters of operation (p<0.0001). The rates were also statistically significant when combat casualties for both theaters and noncombat trauma from the Iraq theater were considered (p<0.001); however, the ratio was not significant among personnel with noncombat trauma from the Afghanistan theater (p=0.083).

Between the two operational theaters regardless of combat status, the duration from injury to development of any type of infection was comparable (median: 6 days). When specific infection syndromes were considered, osteomyelitis had the longest duration from injury to diagnosis (median of 26 and 28 days for Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively), whereas pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and sepsis developed a median of 5 to 7 days after injury (data not shown). Among patients with diagnosed infections, the proportion who had only one infection while hospitalized was also similar between the Afghanistan and Iraq theaters (45% versus 43%, respectively); however, 21% of patients from Afghanistan were diagnosed with at least four infections compared to 9% of patients from Iraq (Table 2). When the data were restricted to noncombat trauma, 83% of personnel from the Afghanistan theater had only one infection compared to 46% from the Iraq theater. Overall, the incidence density rate (number of infections/100 person-days) was higher for military personnel serving in Afghanistan compared to patients with Iraq-related traumatic injuries (2.7 and 2.0, respectively).

Clinical Microbiology and Post-Trauma Antibiotic Prophylaxis

At admission to LRMC, 353 (7%) of wounded personnel were colonized with MDR gram-negative bacteria, as determined from surveillance groin swabs collected at hospital admission. Among the Afghanistan theater, 8% and 0.9% of personnel with combat-related and noncombat injuries were colonized at LRMC admission, respectively. For the Iraq theater, 6% of military personnel with combat-related injuries were colonized with MDR gram-negative bacteria compared to 0.8% of patients with noncombat injuries at LRMC admission. Among the 2513 patients that transferred to a participating U.S. MTF, 258 (10.2%) were colonized with MDR gram-negative bacteria at admission (10.7% and 4.6% of personnel injured in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively). From patients injured in the Afghanistan theater, 2354 colonizing isolates were collected (27% MDR) across all levels of care, whereas 188 isolates were collected from Iraq (18% MDR). Overall, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most common colonizing organisms for both the Afghanistan (43% of E. coli and 28% of K. pneumoniae were MDR, respectively) and Iraq theaters (30% and 12% MDR, respectively). In addition, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus baumannii (ACB) complex isolates were also frequently MDR from both Afghanistan (46%) and Iraq (22%).

While not performed at LRMC, surveillance for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) using nares swabs was conducted at the U.S. MTFs and the rate of colonization was 4.3% overall (95% confidence interval: 3.5–5.1%) with no significant difference between theaters and combat versus noncombat. Specifically, 5.1% of patients from the Iraq theater who transferred to a participating U.S. MTF had MRSA colonization, while it was 4.2% from the Afghanistan theater. In addition, 4.1% and 6.2% of personnel with combat and non-combat injuries were colonized with MRSA.

A total of 1542 unique infections (73.2% of 2106) had a corresponding infection work-up that yielded bacterial growth, of which 80.4% and 49.1% grew gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, respectively. Gram-negative organisms (susceptible and MDR) isolated from infection workups were predominantly collected from combat casualties (25% and 20% in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively), compared to 5% and 6% of personnel with noncombat trauma, respectively. Overall, 68% of the patients with infections had gram-negative bacteria isolated in infection work-ups. Among personnel with combat-related injuries sustained in Afghanistan, the gram-negative organisms most commonly identified during infection workups were Pseudomonas aeruginosa, followed by E. coli and ACB complex, of which 10%, 73%, and 78% were MDR, respectively (Table 3). Combat casualties from Iraq had a similar microbiological profile with 14% of P. aeruginosa, 57% of A. baumannii, and 60% of E. coli determined to be MDR. S. aureus contributed 11.8% to the gram-positive organisms isolated from infection work-ups, of which 44% were MRSA.

Table 3.

Most Common Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated during Infection Workups among Wounded Military Personnel1

| Number of Isolates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Organism | Combat-related Injury |

% MDR | Noncombat Injury | % MDR | |

| Afghanistan Theater | |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 204 | 10 | 1 | 0 | |

| Escherichia coli | 176 | 73 | 3 | 0 | |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus baumannii | 142 | 78 | 2 | 50 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 137 | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 68 | 51 | 0 | 0 | |

| Afghanistan Total2 | 1070 | 33 | 16 | 6 | |

| Iraq Theater | |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7 | 14 | 1 | 0 | |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus baumannii | 7 | 57 | 1 | 0 | |

| Escherichia coli | 5 | 60 | 0 | 0 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Haemophilus influenza | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Iraq Total2 | 40 | 23 | 4 | 0 | |

MDR – multidrug-resistant

Data are collected from all infection work-ups (e.g., wound and blood cultures) among wounded personnel who were transferred from Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) to a TIDOS-participating US military treatment facility (MTF) at all levels of care (LRMC and/or U.S. military treatment facilities). Patients often have serially positive cultures; however, an organism was counted only once per patient. An organism was counted at MDR if it was MDR at any time isolated during repeated isolation.

Only the top five organisms are reported. Total incorporates all organisms collected during infection workups, so it will be more than the sum of the listed organisms.

Overall, 1923 (77%) patients transferred to a participating U.S. MTF received prophylactic antibiotics, of which 1806 (94%) and 117 (6%) sustained injuries in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively. Among the 852 patients who developed an infection, 761 (89%) received prophylactic antibiotics within 48 hours post-injury. In addition, 90% of patients who sustained injuries in Afghanistan and developed infections received prophylactic antibiotics, while it was 72% for Iraq. Patients who received prophylactic antibiotics more commonly had ISS >15 (65%) and sustained injuries via a blast mechanism (72%). Furthermore, 87% of patients with culture growth of MDR organisms (surveillance or infection work-up) received prophylactic antibiotics (data not shown).

In a Chi-square analysis, the association of prophylactic antibiotics and occurrence of any infection was significant (odds ratio [OR]: 3.6; 95th confidence interval [CI]: 2.8–4.6; p<0.0001). The data remained significant when the Afghanistan and Iraq theaters were considered separately (p<0.0001 and p=0.03, respectively). Furthermore, there was also a significant association between prophylactic antibiotic use and isolation of MDR organisms via colonization surveillance or infection work-up among patients (OR: 2.6; CI: 2.0–3.4; p<0.0001).

Risk Factor Analysis

From the patients that transferred to U.S. MTFs, operational theater, circumstances of injury (i.e., combat-related and mechanism), composite ISS, RBC transfusion requirements within 24 hours of injury, open injury, branch of service, MDR gram-negative colonization at LRMC admission, post-trauma antibiotic prophylaxis, and admission to the ICU were examined in a logistic regression analysis (Table 4). The composite ISS and RBC requirements were evaluated as ranked variables. Injuries sustained via an IED blast mechanism and during combat, ISS >15, RBC requirements ≥1 unit, MDR gram-negative colonization, occurrence of open wounds, service in the U.S. Marines, use of prophylactic antibiotics, and admission to the ICU were significantly associated with development of infections in the univariate model (p<0.0001). In addition, injuries that occurred in the Iraq theater were significantly less likely to be associated with the development of infection compared to the Afghanistan theater (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Results of Logistic Regression Models to Evaluate Risk Factors for Any Infectious Complications of Deployment-Related Traumatic Injury

| Parameter | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value | Multivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operational theater | ||||

| Afghanistan | Reference | Reference | ||

| Iraq | 0.56 (0.42–0.75) | <0.0001 | 1.32 (0.87–1.99) | 0.193 |

| Combat-related injury | 7.13 (5.10–9.99) | <0.0001 | 0.60 (0.32–1.15) | 0.124 |

| Branch of Service1 | ||||

| Army | Reference | – | ||

| Marine | 1.66 (1.41–1.95) | <0.0001 | – | |

| Other | 0.83 (0.62–1.12) | 0.220 | – | |

| Mechanism of Injury | ||||

| Gunshot wound | Reference | Reference | ||

| IED blast | 3.26 (2.60–4.08) | <0.0001 | 1.84 (1.35–2.49) | <0.0001 |

| Non-IED blast | 0.99 (0.72–1.37) | 0.937 | 0.91 (0.60–1.37) | 0.639 |

| Other | 0.45 (0.33–0.62) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (0.84–2.66) | 0.174 |

| Injury Severity Score | ||||

| ≤15 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 16–25 | 7.7 (5.9–10.0) | <0.0001 | 1.72 (1.23–2.42) | 0.002 |

| ≥ 26 | 28.5 (23.0–35.4) | <0.0001 | 2.48 (1.81–3.41) | <0.0001 |

| RBC transfusion requirements | ||||

| 0/missing units2 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1–9 units | 9.19 (7.45–11.33) | <0.0001 | 2.50 (1.89–3.30) | <0.0001 |

| 10 – 20 units | 38.69 (29.57–50.64) | <0.0001 | 5.66 (3.97–8.08) | <0.0001 |

| > 20 units | 83.58 (59.50–117.41) | <0.0001 | 10.68 (6.73–16.94) | <0.0001 |

| Injury Type | ||||

| Closed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Open | 6.84 (5.21–9.00) | <0.0001 | 1.37 (0.93–2.03) | 0.114 |

| MDR Gram-negative Colonization at LRMC admission | 2.72 (2.15–3.44) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (0.97–1.99) | 0.075 |

| Use of prophylactic antibiotics within 1st 48 hours | 6.43 (5.16–8.01) | <0.0001 | 1.42 (1.03–1.97) | 0.033 |

| ICU Admission | ||||

| Non-ICU | Reference | Reference | ||

| LRMC only | 4.65 (3.49–6.19) | <0.0001 | 1.98 (1.41–2.76) | <0.0001 |

| U.S. MTFs ± LRMC | 13.59 (10.82–17.06) | <0.0001 | 3.80 (2.85–5.05) | <0.0001 |

CI – Confidence Interval; ICU – intensive care unit; IED – improvised explosive device; LRMC – Landstuhl Regional Medical Center; MDR – multidrug-resistant; MTFs – military treatment facilities; RBC – packed red blood cells plus whole blood

Due to stepwise selection, the branch of service parameters was not included in the multivariate model.

Missing RBC transfusion data are not randomly distributed. Patients with missing RBC data are characterized by lower injury severity scores and shock indices. In addition, the majority of patients with missing RBC data did not sustain a traumatic amputation and were not admitted to the LRMC ICU.

In the multivariate model (Table 4), the risk for infection was highest among patients who received >20 units of RBCs within 24 hours of injury (p<0.0001). Injuries from IEDs (p<0.0001), post-trauma antibiotic prophylaxis (p=0.033), ISS >15 (p<0.002), and ICU admission (p<0.0001) were also significantly associated with the development of infections. Operational theater was not an independent risk factor for an infection following traumatic injury (p=0.193). Furthermore, when the analysis was repeated after separating Afghanistan into two time periods (June 2009–May 2012 and May 2012–December 2013), there was no significant association with operational theater (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This analysis assessed characteristics and rates of infectious complications among 5290 U.S. service members with deployment-related injuries in association with two combat operational theaters (Iraq and Afghanistan). Overall, a higher rate of infection was observed with the Afghanistan theater compared to Iraq during a contemporaneous period (2.7 versus 2.0 infections per 100 person-days). After controlling for injury severity and other factors, there was no statistical association between operational theater and the risk of developing an infection. It is also notable that personnel with noncombat injuries also had high rates of infection (1.0 and 2.0 per 100 person-days for Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively). Our data corroborate prior analyses which reported associations of infectious consequences among wounded military personnel with the severity and mechanism of injury.14,15,21–23

Measures of injury severity (i.e., ICU admission, ISS, and hemorrhage as indicated by RBC transfusion requirements within 24 hours) primarily explain the statistical difference in infection rate independent of operational theater as data in our analysis suggest that injuries sustained in Afghanistan were generally more severe and likely due to the high proportion of blast injuries and dismounted status during the same time period. In addition, large-volume transfusions of blood products have been previously shown to be an independent risk factor for infection following deployment-related trauma, possibly due to inducing a transient state of immunosuppression.22,23 Furthermore, the association of prophylactic antibiotics within 48 hours is also consistent with use within a higher at-risk population.5 Patients who received prophylactic antibiotics were observed to have higher injury severity as indicated by increased proportion with ISS >15, ICU admissions, and predominance of blast injuries. Nonetheless, a more detailed exploration of antimicrobial regimens and related infection outcomes is warranted. The role of antecedent bacterial colonization and subsequent infection is unknown24 and the variable was not statistically significant in the risk factor analysis (p=0.08), our results suggest that colonization with MDR gram-negative organisms may be a risk factor and should be investigated further. The colonization data are consistent with our prior analysis that found similar annual rates of MDR gram-negative bacilli colonization over a three-year period (2009–2012).25 It is also noteworthy that the rate of MDR gram-negative colonization at admission to the U.S. MTFs was higher than the rate of MRSA colonization (10.2% versus 4.3%).

Although a great deal of focus has been placed on injuries sustained during combat, a high rate of infection was found among personnel with noncombat injuries. Many noncombat injuries in an operational zone involve mechanisms such as motor vehicle collisions, falls, and burns, which often result in open wounds. In a prior retrospective analysis of 4566 military personnel with noncombat injuries not sustained in a war zone found that 8.2% had at least one related infection. Pneumonia was predominant (4%) with a lower proportion of cellulitis/wound infections (2.4%) and sepsis (0.9%).7 When considering all noncombat trauma patients from both theaters of operation, 15% had at least one infection, with pneumonia and SSTIs contributing the greatest proportion to unique infections.

While the majority of previous analyses have not examined data on a per theater basis, infection rates from the recent conflicts have been published. Data from 16,742 deployment-injured patients were collected from a trauma registry and determined an infection rate of 5.5% (annual range: 0.6–10.9%).14 Moreover, an early evaluation from the TIDOS project reported 5% of LRMC admissions and approximately 27% of patients transferred to the U.S. developed infections.3 In our analysis, the proportion of infections among the total number of patients admitted to LRMC was consistent with the prior analyses (5%); however, the overall infection rate among wounded personnel who transferred to one of the participating U.S. MTFs was higher (34%). Analysis of data from the United Kingdom has also found a high rate of infection related to extremity injuries (24%), which corresponds to our finding of the predominance of SSTIs and minor contribution of osteomyelitis.26

In general, the rate of infections among wounded personnel from the Iraq theater was lower than Afghanistan (2.0 and 2.7 infections per 100 person-days, respectively). One reason for the differing infection rates may be the reduction of combat-related injuries as military operations ceased in Iraq during the study period (OIF concluded in August 2010 and was followed by OND peacekeeping efforts); however, it is important to note that despite the shift to peacekeeping efforts, a risk of combat-related injuries still occurs. Specifically, 42% of the injuries sustained in Iraq during OND were combat-related. Another possible explanation is that as combat operations transitioned, patterns of injury changed due to differences in military tactics (on both sides) affecting casualties. During 2010, as combat operations were concluding in Iraq and increasing in Afghanistan, the number of traumatic amputations substantially increased. Between 2010 and 2011, the amputation rate rose from 3.5 to 14 per 100 combat support facility trauma admissions, and was primarily the result of dismounted patrols encountering IEDs in Afghanistan.9,27 The consequent dismounted complex blast injuries were characterized by lower extremity amputations (unilateral or bilateral), upper extremity amputations, pelvic and urogenital injuries, and spinal injuries.27 United Kingdom military personnel were also greatly impacted by this injury pattern with 2.8% of combat casualties sustaining bilateral lower limb amputations over a six-year period.11 Due to the severity of these injuries, patients generally required large-volume blood transfusions (>10 units), debridements, and further surgical procedures in response to complications, such as infections.11,27,28 One example was the unexpected surge in invasive fungal wound infections among military personnel who sustained blast injuries in Afghanistan. Specifically, nearly 7% of the combat casualties admitted to LRMC between June 2009 and August 2011 were diagnosed with an invasive fungal wound infection.29–31 A similar emergence of invasive fungal wound infections was also reported among United Kingdom military personnel with blast injuries sustained in Afghanistan.32

While information is available on injury patterns and infection rates,2,3,14,15,28,33–35 further data defining the progression of infections and resultant short- and long-term outcomes are necessary. The findings in this military setting provide support for the identification of infection risk factors related to trauma sustained during deployment; however, the feasibility of using these factors in predictive modeling with clinical care application still needs to be assessed. Nonetheless, this information emphasizes the need for forward medical support in the deployed setting and a high index of suspicion for infectious complications following traumatic injuries, regardless of whether they are sustained during combat or noncombat. A limitation of this analysis that should be considered is that infection data were collected exclusively from patients who transferred to a TIDOS-participating U.S. MTFs (approximately 48% of subjects admitted to LRMC). In general, these patients experienced more severe injuries compared to those who transferred to U.S. MTFs other than the ones included in this analysis. Thus, the applicability of data reported herein to all U.S. injured service members is uncertain.

Combat casualty care is continuously advancing as new technology and data become available; however, infectious complications remain a serious cause of morbidity. The implementation of epidemiologic and surveillance projects, such as TIDOS and the Multidrug-Resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network (MRSN),36 are integral in informing the military health system on these key issues. With the emergence of new challenges, such as MDR bacterial organisms, healthcare-associated transmission across evacuation and MTFs, and invasive fungal wound infections, further examination of infection predictive factors, microbiological findings, real-time surveillance and support for control of outbreaks of MDR bacterial organisms through the MRSN, and specific infectious disease syndromes among deployed service members is warranted to improve crucial elements of combat casualty care including trauma systems, infection control policies, early detection, and antimicrobial selection.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study team of clinical coordinators, microbiology technicians, data managers, clinical site managers, and administrative support personnel for their tireless hours to ensure the success of this project.

Funding sources: Supported by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense (DoD) program executed through the Uniformed Services University grant IDCRP-024, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072, and the Department of the Navy under the Wounded, Ill, and Injured Program.

Footnotes

A portion of this material was presented at the Advanced Technology Applications for Combat Casualty Care (ATACCC) 2011, August 15–18, 2011, Fort Lauderdale, FL; and the Military Health System Research Symposium (MHSRS), August 12–15 2013, Fort Lauderdale, FL.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., National Institutes of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services, Brooke Army Medical Center, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, U.S. Army Medical Department, U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of Defense (DoD) or the Departments of the Army, Navy or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author Contribution: I/We certify that all individuals who qualify as authors have been listed; each has participated in the conception and design of this work, the analysis of data (when applicable), the writing of the document, and the approval of the submission of this version; that the document represents valid work; that if we used information derived from another source, we obtained all necessary approvals to use it and made appropriate acknowledgements in the document; and that each takes public responsibility for it. Nothing in the presentation implies any Federal/DOD/DON endorsement. Authors acknowledge that research protocol (IDCRP-024) received applicable Uniformed Services University Institutional Review Board review and approval.

REFERNCES

- 1.Murray CK, Hinkle MK, Yun HC. History of infections associated with combat-related injuries. J Trauma. 2008;64(3 Suppl):S221–S231. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163c40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CK. Epidemiology of infections associated with combat-related injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan. J Trauma. 2008;64(3 Suppl):S232–S238. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163c3f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tribble DR, Conger NG, Fraser S, Gleeson TD, Wilkins K, Antonille T, et al. Infection-associated clinical outcomes in hospitalized medical evacuees after traumatic injury: trauma infectious disease outcome study. J Trauma. 2011;71(1 Suppl):S33–S42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318221162e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson NE, Sanders JW, Moran KA. In harm's way: infections in deployed American military forces. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(8):1045–1051. doi: 10.1086/507539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospenthal DR, Murray CK, Andersen RC, Bell RB, Calhoun JH, Cancio LC, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of infections associated with combat-related injuries: 2011 update: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Surgical Infection Society. J Trauma. 2011;71(2 Suppl 2):S210–S234. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318227ac4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eardley WG, Brown KV, Bonner TJ, Green AD, Clasper JC. Infection in conflict wounded. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1562):204–218. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun HC, Blackbourne LH, Jones JA, Holcomb JB, Hospenthal DR, Wolf SE, et al. Infectious complications of noncombat trauma patients provided care at a military trauma center. Mil Med. 2010;175(5):317–323. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Department of Defense. OIF/OEF Casualty Update. [accessed June 1, 2015]; Available at http://www.defense.gov/news/casualty.pdf.

- 9.Krueger CA, Wenke JC, Ficke JR. Ten years at war: comprehensive analysis of amputation trends. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S438–S444. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318275469c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoencamp R, Idenburg FJ, Hamming JF, Tan EC. Incidence and epidemiology of casualties treated at the Dutch Role 2 enhanced medical treatment facility at multi national base Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan in the period 2006–2010. World J Surg. 2014;38(7):1713–1718. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penn-Barwell JG, Bennett PM, Kay A, Sargeant ID on behalf of the Severe Lower Extremity Combat Trauma Study Group. Acute bilateral leg amputation following combat injury in UK servicemen. Injury. 2014;45(7):1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eastridge BJ, Jenkins D, Flaherty S, Schiller H, Holcomb JB. Trauma system development in a theater of war: experiences from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1366–1372. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000245894.78941.90. discussion 72–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eastridge BJ, Costanzo G, Jenkins D, Spott MA, Wade C, Greydanus D, et al. Impact of Joint Theater Trauma System initiatives on battlefield injury outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;198(6):852–857. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray CK, Wilkins K, Molter NC, Li F, Yu L, Spott MA, et al. Infections complicating the care of combat casualties during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2011;71(1 Suppl):S62–S73. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182218c99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen K, Riddle MS, Danko JR, Blazes DL, Hayden R, Tasker SA, et al. Trauma-related infections in battlefield casualties from Iraq. Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):803–811. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251707.32332.c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott P, Deye G, Srinivasan A, Murray C, Moran K, Hulten E, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex infection in the US military health care system associated with military operations in Iraq. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(12):1577–1584. doi: 10.1086/518170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acinetobacter baumannii infections among patients at military medical facilities treating injured U.S. service members, 2002–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(45):1063–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champion HR, Holcomb JB, Lawnick MM, Kelliher T, Spott MA, Galarneau MR, et al. Improved characterization of combat injury. J Trauma. 2010;68(5):1139–1150. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d86a0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections. [accessed June 1, 2015]; Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/17pscnosinfdef_current.pdf.

- 20.Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. Protocol multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) and Clostridium difficile-associated disease (CDAD) module. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [accessed December 15, 2015]. The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Manual. Patient safety component. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/12pscMDRO_CDADcurrent.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray CK, Wilkins K, Molter NC, Yun HC, Dubick MA, Spott MA, et al. Infections in combat casualties during Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2009;66(4 Suppl):S138–S144. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d894c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunne JR, Hawksworth JS, Stojadinovic A, Gage F, Tadaki DK, Perdue PW, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion in combat casualties: a pilot study. J Trauma. 2009;66(4 Suppl):S150–S156. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d9561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunne JR, Riddle MS, Danko J, Hayden R, Petersen K. Blood transfusion is associated with infection and increased resource utilization in combat casualties. Am Surg. 2006;72(7):619–625. discussion 25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hospenthal DR, Crouch HK, English JF, Leach F, Pool J, Conger NG, et al. Multidrug-resistant bacterial colonization of combat-injured personnel at admission to medical centers after evacuation from Afghanistan and Iraq. J Trauma. 2011;71(1 Suppl):S52–S57. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31822118fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weintrob AC, Murray CK, Lloyd B, Li P, Lu D, Miao Z, et al. Active surveillance for asymptomatic colonization with multidrug-resistant gram negative bacilli among injured service members - a three year evaluation. MSMR. 2013;20(8):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown KV, Murray CK, Claspar JC. Infectious complications of combat-related mangled extremity injuries in the British military. J Trauma. 2010;69(suppl 1):S109–S115. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e4b33d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ficke JR, Eastridge BJ, Butler F, Alvarez J, Brown T, Pasquina P, et al. Dismounted complex blast injury report of the Army Dismounted Complex Blast Injury Task Force. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S520–S534. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, Gajewski DA, Keeling JJ, Andersen RC, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(4):232–237. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a53130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez C, Weintrob AC, Shah J, Malone D, Dunne JR, Weisbrod AB, et al. Risk factors associated with invasive fungal infections in combat trauma. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014;15(5):521–526. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez CJ, Weintrob AC, Dunne JR, Weisbrod AB, Lloyd BA, Warkentien T, et al. Clinical relevance of mold culture positivity with and without recurrent wound necrosis following combat-related injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(5):769–773. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weintrob AC, Weisbrod AB, Dunne JR, Rodriguez CJ, Malone D, Lloyd BA, et al. Combat trauma-associated invasive fungal wound infections: epidemiology and clinical classification. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(1):214–224. doi: 10.1017/S095026881400051X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evriviades D, Jeffery S, Cubison T, Lawton G, Gill M, Mortiboy D. Shaping the military wound: Issues surrounding the reconstruction of injured servicemen at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1562):219–230. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conger NG, Landrum ML, Jenkins DH, Martin RR, Dunne JR, Hirsch EF. Prevention and management of infections associated with combat-related thoracic and abdominal cavity injuries. J Trauma. 2008;64(3 Suppl):S257–S264. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163d2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray CK, Obremskey WT, Hsu JR, Andersen RC, Calhoun JH, Clasper JC, et al. Prevention of infections associated with combat-related extremity injuries. J Trauma. 2011;71(2 Suppl 2):S235–S257. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318227ac5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segrt B. Particularities of the therapeutic procedures and success in treatment of combat-related lower extremities injuries. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2014;71(3):239–244. doi: 10.2298/vsp1403239s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesho EP, Waterman PE, Chukwuma U, McAuliffe K, Newmann C, Julius MD, et al. The Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research (ARMoR): The US Department of Defense response to escalating antimicrobial resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):390–397. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]