Abstract

Although pelvic pain is a symptom of several structural anorectal and pelvic disorders (eg, anal fissure, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease), this comprehensive review will focus on the three most common nonstructural, or functional, disorders associated with pelvic pain: functional anorectal pain (ie, levator ani syndrome, unspecified anorectal pain, and proctalgia fugax), interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The first two conditions occur in both sexes, while the latter occurs only in men. They are defined by symptoms, supplemented with levator tenderness (levator ani syndrome) and bladder mucosal inflammation (interstitial cystitis). Although distinct, these conditions share several similarities, including associations with dysfunctional voiding or defecation, comorbid conditions (eg, fibromyalgia, depression), impaired quality of life, and increased health care utilization. Several factors, including pelvic floor muscle tension, peripheral inflammation, peripheral and central sensitization, and psychosocial factors, have been implicated in the pathogenesis. The management is tailored to symptoms, is partly supported by clinical trials, and includes multidisciplinary approaches such as lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic, behavioral, and physical therapy. Opioids should not be avoided, and surgery has a limited role, primarily in refractory interstitial cystitis.

Keywords: Abdominal Pain, Chronic Pain, Constipation, Diarrhea, Gastroenterology

Introduction

Anorectal and pelvic pain is a manifestation of several structural and functional disorders affecting the anorectum, urinary bladder, reproductive system, and the pelvic floor musculature and its innervation. In contrast to structural diseases such as endometriosis, the pelvic pain in functional disorders cannot be explained by a structural or other specified pathologic process.1 Functional disorders are classified into anorectal (eg, proctalgia fugax, levator ani syndrome, and unspecified anorectal pain), bladder (eg, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome [IC/BPS]), and prostate syndromes (eg, chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome [CP/CPPS]). IC/BPS is primarily diagnosed in women, whereas CP/CPPS is a diagnosis exclusive to men. Historically, these conditions have been regarded as distinct, and this review discusses them separately. However, more recent reviews emphasize the shared features between IC/BPS and CP/CPPS, which is captured by the term urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes.2 These urogynecologic syndromes also share several features with anorectal pain syndromes (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Cardinal Features of Chronic Functional Anorectal and Urogynecologic Disorders.

|

Table 2. Clinical Features of Functional and Chronic Anorectal and Pelvic Pain Disorders.

| Levator Ani Syndrome | Proctalgia Fugax | Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome | Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age | 30 to 60 years | Any age (rare before puberty) | 45 to 60 years | Older than 50 years |

| Sex difference | Men<Women | Men=Women | Men<Women | Men |

| Pain characteristics | ||||

| Quality | Vague, dull ache or pressure sensation | Cramping, gnawing, aching, or stabbing | Varying qualities of pain, pressure, or discomforta | Varying qualities of pain, pressure, or discomforta |

| Duration | 30 minutes or longer | A few seconds to several minutes | Varying durations (from minutes to days) | Varying durations (from minutes to days) |

| Typical location | Rectum | Rectum | Suprapubic area | Perineum |

| Pain at other sites | No | No | Yes (pelvic and extragenital area) | Yes (pelvic and extragenital area) |

| Precipitating factors | Sitting for long periods Stress Sexual intercourse Defecation Childbirth Surgeryb |

Stress Anxiety |

Intake of certain foods or drinks Stress Sexual intercourse Menstrual cycle |

Urination Ejaculation Stress |

| Associated symptoms | ||||

| Urinary symptoms | No | No | Yesc | Yesc |

| Sexual dysfunction | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Psychosocial symptoms | Possible | Possible | Yes | Yes |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Internal pelvic tender points | Yes (puborectalisd) | No | Yes | Yes (including prostatee) |

| External pelvic tender points | No | No | Yes | Yes |

An increase in discomfort with bladder filling and relief with voiding.

Herniated lumbar disc, hysterectomy, or low anterior resection.

No urge urinary incontinence and no response to overactive bladder treatment (eg, anticholinergics).

Asymmetric (left side>right side) and predictor of successful biofeedback therapy.

Extreme tenderness upon gentle palpation of the prostate should raise suspicion for acute bacterial prostatitis or even a prostatic abscess.

Expert panels have relied on evidence, supplemented by the Delphi process, to develop diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines for these disorders. The aim of this review is to summarize the evidence on the epidemiology, natural history, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of these conditions. This review, which is updated from an earlier review,3 incorporates the most recent recommendations, including the Rome Criteria on anorectal disorders published in May 2016,4 the American Urological Association guidelines for IC/BPS from September 2014,5 and a Prostatitis Expert Reference Group document on CP/CPPS from 2015.6

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Ovid EMBASE. While the topics overlapped, each was done separately, and building on previous systematic reviews,5,6 the searches extended back to 1995 for anorectal and mixed pain syndromes, 2008 for chronic pain, and 2014 for chronic prostatitis,. The MeSH term Pelvic pain/ was expanded to include dysmenorrhea, piriformis syndrome, pelvic girdle pain combined with either MeSH terms chronic disease/ or chronic pain/. This concept was also searched by chronic within 3 words adjacent to “pelvic pain” as text words. Chronic prostatitis was similarly searched using Prostatitis/[MeSH] and chronic pain/[MeSH] or chronic within 2 words of prostatitis. For anorectal pain the only MeSH terms were quite general; the search used text words “levator ani”, “proctalgia fugax”, puborectal myalgia, coccygodynia, and anorectal within 2 words of pain*. The strategies were then translated in the EMBASE vocabulary EMTREE, or text words, and run. Duplicates were removed, giving precedence to the MEDLINE results.

Functional Anorectal Pain

Introduction

Based on the duration of pain and the presence or absence of anorectal tenderness, functional anorectal pain disorders are categorized into 3 conditions: levator ani syndrome, unspecified anorectal pain, and proctalgia fugax. Patients with levator ani syndrome and unspecified anorectal pain have chronic pain or intermittent pain with prolonged episodes. Levator ani syndrome is associated with tenderness to palpation of the levator ani muscle;7 unspecified anorectal pain is not. By contrast, the pain in proctalgia fugax is brief (ie, lasts for seconds to minutes) and occurs infrequently (ie, once a month or less often). See Table 3.8-15

Table 3. Symptom Questionnaires for Chronic Pelvic Disorders.

| Condition | Questionnaire |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hypertrophy | American Urological Association Symptom Index (SI)8 |

|

| |

| Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) | National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis |

| Symptom Index9 | |

| International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)10 | |

| Urinary, Psychosocial, Organ-specific, Infection, | |

| Neurological/systemic, and Tenderness (UPOINT)11 | |

|

| |

| Interstitial cystitis and bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) | Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index12 |

|

| |

| Functional anorectal pain | Rome III Questionnaire13 |

| Psychosocial assessment | Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)14 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)14 | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)15 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | |

Epidemiology

In the only population-based survey, which was conducted in a sample of United States (US) householders in 1990, the prevalence of anorectal pain, levator ani syndrome, and proctalgia fugax, as determined by a symptom-based questionnaire (Table 3), was 11.6% (11.1% in men and 12.1% in women), 6.6% (5.7% in men and 7.4% in women), and 8% (7.5% in men and 8.3% in women), respectively.16 The prevalence of anorectal pain was higher in those younger than 45 years (14%, vs 9% in those ≥45 years). Similar trends were observed for levator ani syndrome and proctalgia fugax. Approximately 8.3% with functional anorectal pain, 11.5% with levator ani syndrome, and 8.4% with proctalgia fugax reported they were currently too sick to work or go to school.16

Pathophysiology

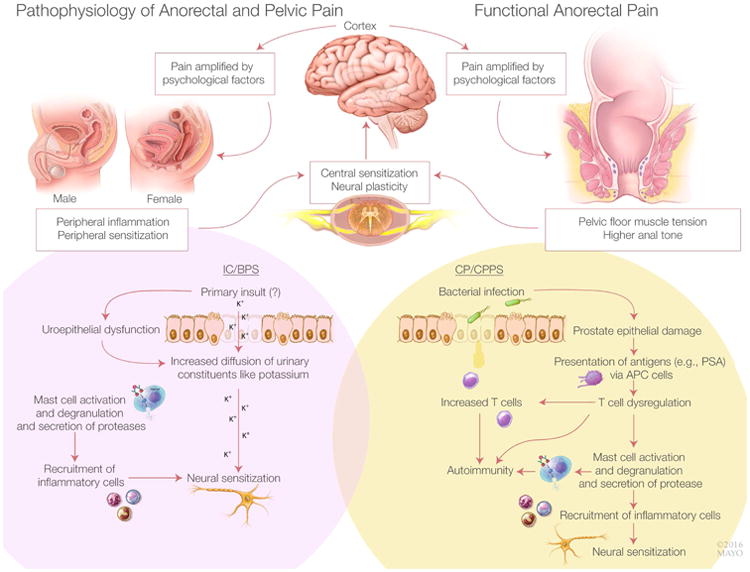

In levator ani syndrome, noncontrolled studies have implicated a role for pelvic floor muscle spasm, increased anal resting pressures,17 and dyssynergic defecation, which is characterized by rectoanal incoordination during defecation and often improves with biofeedback therapy (Figure 1).18 In proctalgia fugax, the short duration and sporadic, infrequent pain episodes have limited the identification of physiologic mechanisms. Excessive colonic19 and anal smooth muscle contraction20,21 have been observed. Hereditary proctalgia fugax is associated with constipation and hypertrophy of the internal anal sphincter.22

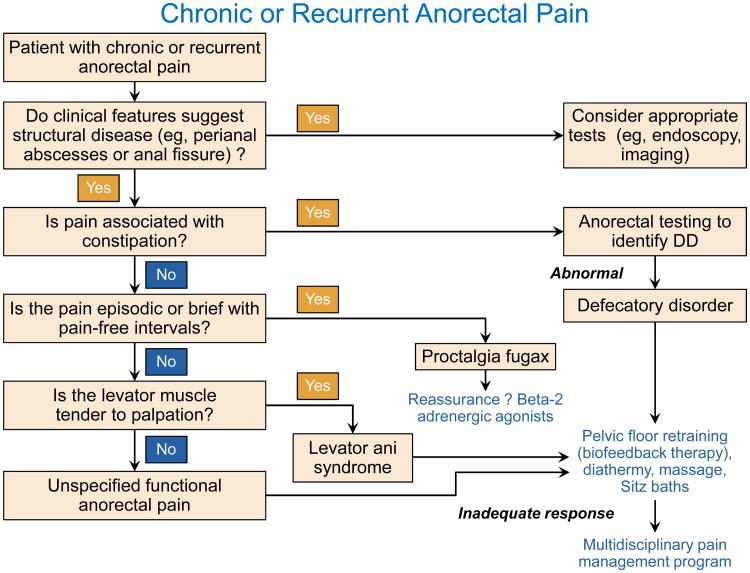

Figure 1.

Model for Chronic Anorectal Pain (upper panel), Interstitial Cystitis and Painful Bladder Syndrome (IC/BPS, lower left panel) and Chronic Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS, lower right panel). Common to all conditions are peripheral (visceral) and central nervous system dysfunctions that often perpetuate each other. Our understanding of peripheral dysfunctions is largely derived from animal models rather than humans. In IC/BPS, the initial insult responsible for uroepithelial dysfunction is unknown. Thereafter, increased permeability may predispose to increased transepithelial diffusion of urinary constituents (e.g., potassium), which ultimately activate mast cells and T cells, leading to peripheral, then central sensitization. In CP/CPPS, bacterial infection may be the initial insult that activates a similar cascade of events. In chronic anorectal pain, a role for increased pelvic floor tension has been proposed. Chronic pain is amplified by psychological factors.

Clinical Features

Among patients with constant or recurrent rectal pain, the pain is (ie, levator ani syndrome) or is not (ie, unspecified anorectal pain) associated with tenderness to palpation of the levator ani muscle (Table 2). When the pain is episodic, the episodes last 30 minutes or longer. The pain is a vague, dull ache or pressure sensation high in the rectum that is often worse in the seated than the standing or lying positions. Patients with the levator ani syndrome often have psychosocial distress (eg, depression and anxiety) and impaired quality of life (QoL).23 Levator spasm, puborectalis syndrome, pyriformis syndrome, chronic proctalgia, and pelvic tension myalgia are other terms used to describe chronic rather than brief pain (ie, proctalgia fugax).

Proctalgia fugax is characterized by recurrent episodes of pain localized to the rectum and unrelated to defecation. In a series of 54 patients, attacks generally occurred suddenly, during the day or at night, and once a month.24 In some patients, attacks were precipitated by stressful life events or anxiety.25 The nonradiating cramp, spasm, or stabbing pain without concomitant symptoms lasted, on average, for 15 minutes and dissipated spontaneously.26

Management

Diagnostic tests to exclude an structural disorder and to identify a defecatory disorder should be performed as necessary (Figure 2).27 Anoscopy may be necessary to identify anal fissures and hemorrhoids; the examination should be performed under anesthesia for patients with severe pain. Chronic proctosigmoiditis, which is generally due to inflammatory bowel disease and, rarely, ischemia, can be identified by flexible sigmoidoscopy. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging may be necessary to identify perirectal abscesses or fistulae. In addition to features of a defecatory disorder (eg, impaired anal relaxation, paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis, or impaired rectal evacuation),27,28 dynamic imaging (eg, magnetic resonance or barium proctography) may also identify other abnormalities (eg, high-grade internal rectal prolapse), which may reflect incidental findings or excessive straining rather than a cause of chronic pain.29,30 Except for 2 controlled studies, most therapeutic trials for chronic intractable anorectal pain have been noncontrolled. One controlled trial randomly assigned 157 patients with chronic proctalgia to receive 9 sessions of electrical stimulation, or digital massage of the levator ani and warm sitz baths, or pelvic floor biofeedback plus psychological counseling.18 The randomization was stratified based on tenderness to palpation of the pelvic floor muscles during a digital rectal examination. Among patients who reported such tenderness, 87% reported adequate relief of rectal pain after biofeedback therapy, 45% after electrical stimulation, and 22% after massage. This improvement was maintained 12 months later. Impaired pelvic floor relaxation and rectal balloon expulsion also predicted a response to biofeedback therapy. Biofeedback therapy improved rectoanal coordination during evacuation. By contrast, patients who did not report tenderness to palpation did not respond to any of these treatments. In another controlled study, injections of botulinum toxin into the levator ani muscle administered twice over 3 months were not superior to placebo in 12 patients with levator ani syndrome.31

Figure 2. Algorithm for managing anorectal pain.

Modified with permission from Bharucha AE, Wald AM. Anorectal disorders. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2010; 105(4):786-94.

A noncontrolled study observed that sitz baths improved chronic anorectal pain.32 Besides counter-irritation, hot water may reduce anal pressures.32 A combination of approaches (ie, massage, sitz baths, muscle relaxants, and diathermy) were effective in 68% of 316 patients with levator syndrome.7 In another noncontrolled study of 158 patients with chronic anorectal pain, symptoms improved after biofeedback therapy (17/29 patients [58.6%]), tricyclic antidepressants (10/26 patients [38.5%]), botulinum toxin injection (5/9 patients [55.5%]), and sacral nerve stimulation (2/3 patients [66.6%]).33

The efficacy of another method, ultrasound-guided injection of either local anesthetic or alcohol for pelvic nerves (eg, pudendal nerve), has not been proved. Three small noncontrolled case series with fewer than 30 patients total suggested that sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) may benefit some patients.34-36 In our opinion, SNS should not be used to manage levator ani syndrome outside of clinical trials.

We have evaluated patients with refractory anorectal pain who had persistent symptoms despite surgical interruption of the puborectalis muscle. This procedure is of unproven benefit and may lead to fecal incontinence. Likewise, there is little evidence that surgery to treat internal rectal prolapse or other incidental abnormalities observed with dynamic magnetic resonance proctography will improve chronic anorectal pain. Rather, patients with refractory pain, of whom most, in our experience, have psychosocial comorbid conditions, should be referred to a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program. These programs integrate physical therapy, occupational therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy in an intensive, interdisciplinary, outpatient setting. The emphasis is on physical reconditioning and elimination of medications for pain (eg, opioids) and other symptoms (eg, benzodiazepines), along with activity management and behavior therapy.37 Most pain rehabilitation centers offer daily treatment for 2 to 4 weeks. Patients who benefit from this approach do so because of a change in their behavior, beliefs, and physical status. The efficacy of these programs has been reported for chronic pain, including chronic abdominal pain, but not specifically for chronic pelvic pain.38

For most patients with proctalgia fugax, the emphasis is on reassurance and explanation. The episodes of pain are so brief and infrequent that remedial treatment is impractical and prevention is not feasible. The inhaled β2-adrenergic agonist salbutamol was more effective than placebo for shortening the duration of episodes of proctalgia.39

Chronic Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

Definition

A syndrome exclusive to men, CP/CPPS is “characterized by chronic pain in the perineum, tip of the penis, suprapubic region, or scrotum, which is often worsened with voiding or ejaculation, in the absence of an organic disorder”.3 CP/CPPS (type III prostatitis in the National Institutes of Health classification) constitutes the vast majority (ie, >90%) of cases of symptomatic prostatitis.40 Other diagnoses in this classification include acute bacterial prostatitis (type I), chronic bacterial prostatitis (type II), and asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (type IV).

Epidemiology

The condition affects men of all ages and has a prevalence of 2% to 10%.40,41 Patients with CP/CPPS account for approximately 2 million medical office visits per year in the US.42

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of CP/CPPS is unclear. Putative mechanisms are depicted in Figure 1. Historically, CP has been regarded as an infectious disease and treated with antibiotics. The infection is diagnosed by culturing bacteria from urine or expressed prostatic secretions. However, most bacteria resist cultivation, perhaps because most chronic bacterial infections are associated with a biofilm mode of growth that is difficult to culture.43 A molecular technique not dependent on cultures observed that the overall species and genus composition differed only in the initial urine stream between urologic CPPS and controls, with Burkholderia cenocepacia overrepresented in urologic CPPS.44 By contrast, midstream or postprostatic massage samples were not significantly different. The absence of microbiota does not exclude the possibility that CPPS is initiated by infection, although chronic inflammation and pain may persist after the infection has been cleared.45 Prostate biopsies demonstrate inflammation in 33% of patients with CP/CPPS.46 Neurogenic processes, autoimmune injury, and mast cells may contribute to inflammation. However, this inflammation does not correlate with the severity of pain.47 The concentration of nerve growth factor—which is involved in nerve function, regrowth after nerve injury, and neurogenic inflammation—in expressed prostatic secretions is higher in CP/CPPS than in asymptomatic controls. Also, nerve growth factor concentrations are correlated with the severity of pain.48 In some patients, there is evidence of an autoimmune process.45 Expressed prostatic secretions in men with CPPS have increased mast cell tryptase and nerve growth factor.49 Peripheral inflammation may lead to central sensitization, which may perpetuate increased visceral sensitivity.50 Psychological stress is common 51 and may also increase visceral sensitivity.52

Clinical Features

CP/CPPS is associated with various clinical features, such as urogenital pain, urinary symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and psychosocial symptoms (Table 2). Perineal pain is most frequent; other locations are the testes, pubis, and penis. Between 39% and 68% of patients have lower urinary tract symptoms. A meta-analysis observed an increased risk (pooled odds ratio, 3.02; 95% CI, 2.18-4.17) of erectile dysfunction in patients with CP/CPPS.53

A large case-control study demonstrated that the urological chronic pain syndromes (ie, CP/CPPS and IC/BPS) were associated with not only negative effects but also a broader spectrum of psychosocial disturbances, including “higher levels of current and lifetime stress, poorer illness coping, increased self-report of cognitive deficits, and more widespread pain symptoms compared with sex- and education-matched” healthy men and women.54 Case patients also had greater difficulties with sleep and functioning in sexual relationships. Indeed, the QoL in patients with CP/CPPS is similar to that after myocardial infarction or Crohn disease.55

Between 22% and 31% of patients with CP/CPPS have symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.6 When compared with age-matched controls, men who have CP/CPPS have a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, neurologic disease, and sinusitis.56

The physical examination should include palpation of pelvic muscles (which may be tender and may not contract and/or relax appropriately), the bladder and prostate (which may be enlarged), and the anal sphincter (which may be weak and/or not relax adequately).

Diagnostic tests

A history and physical examination (including digital rectal examination), urinalysis, and urine cultures should be performed. A pre- and post-prostate massage urine [test] is as sensitive and specific as the 4-glass test for diagnosing chronic bacterial prostatitis.57 Other tests for consideration include prostate ultrasound, urethral swab, urodynamic studies, and prostate-specific antigen measurement.5 Very rarely, perineal pain may be a manifestation of a lumbosacral spinal cord lesion.58 Spinal imaging should be considered if other neurologic symptoms or signs are present.

Management

Therapeutic options are of variable efficacy (Table 4).59-66 Because the clinical features are heterogeneous and vary among patients, it has been suggested that one size may not fit all. Rather, therapy individualized to the specific symptom(s) may be preferable.67 The UPOINT (Urinary, Psychosocial, Organ-specific, Infection, Neurological/systemic, and Tenderness) scoring system includes 6 domains: 1) irritative or obstructive urinary symptoms, 2) psychosocial issues, 3) organ-specific (bladder or prostate) symptoms (pain associated with bladder filling and relieved with voiding, prostate tenderness, and leukocytosis in expressed prostatic specimens), 4) infections (positive prostatic fluid cultures in absence of urinary tract infection, urethritis), 5) neurologic/systemic symptoms (pain outside the pelvis, systemic pain syndromes [eg, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome]), and 6) tenderness (pelvic floor spasm, muscle trigger points in abdomen/pelvis).68 Limited evidence from a noncontrolled prospective study of 100 patients in which management was guided by the UPOINT assessment indicated that symptoms improved significantly in 84% of patients and by 50% or more in 51%.68 Although this study was not controlled, these response rates were comparable to or better than those observed in other controlled trials with monotherapy.

Table 4. Treatment of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome.

| Category | Examples | Evidence Strengtha | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral pharmacotherapy | |||

| Antibiotics | Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, tetracycline | A5 | Initial treatment often includes a 4-6 week course of antibiotics Consider repeating antibiotics only in patients who have positive urine cultures or partially respond to the first course |

| α-blockers | Uroselective: tamsulosin, alfuzosin, doxazosin Others: terazosin, silodosin |

A5 | More effective against lower urinary tract symptoms than pain Uroselective agents have a lower risk of orthostatic hypotension and syncope |

| Phytotherapy | Rye pollen extract, quercetin | B59 | Should be considered for patients with inadequate symptom control to initial antibiotics, α-blockers and analgesics6 |

| Analgesics | Acetaminophen, NSAIDs | C60 | Avoid narcotics |

| Neuromodulators | Amitriptyline, gabapentinoids (eg, pregabalin or gabapentin), SNRIs (eg, duloxetine) | B61 | Early use of neuromodulating agents in pain of neuropathic origin |

| Hormonal agents | Finasteride, dutasteride, mepartricin | C62 | Not recommended as monotherapy Hormonal agents considered only if benign prostatic hypertrophy is coexistent |

| 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors | Sildenafil, mirodenafil, tadalafil | C63 | Coexisting erectile dysfunction |

| Adjunct approaches | |||

| Physical therapy and acupuncture | Pelvic floor biofeedback Trigger-point injection Percutaneous/transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation(PTNS) Electroacupuncture Aerobic exercise |

C64 | Pain or tenderness in the lower abdominal or pelvic musculature Pelvic floor physical therapy not only improved overall symptoms but also improved sexual dysfunction |

| Surgical approaches | |||

| Sacral nerve stimulation | Sacral neuromodulation (InterStim; Medtronic) | C65 | Efficacy unknown |

| Surgery | Prostatectomy Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) Transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) of the prostate Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) |

D66 | Efficacy unknown |

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Level A: meta-analysis of well-designed randomized controlled trials; B: at least 1 well-designed randomized controlled trial; C: at least 1 well-designed observational study; D: case series.

Supported by strong evidence, first-line approaches include antibiotics for infections and α-blockers or anticholinergic medications for urinary symptoms69 (see also Table 4). Simple analgesics (acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), followed if necessary by neuromodulators, tricyclic antidepressants (eg, nortriptyline, amitriptyline), or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine) should be considered for pain. Phytotherapy (eg, rye pollen extract and the bioflavonoid quercetin) also improved pain and QoL in small controlled clinical trials.6,69 For erectile dysfunction, 5α-reductase inhibitors are recommended in patients with coexistent benign prostatic enlargement.

Pelvic floor physical therapy can improve overall symptoms and sexual dysfunction.70 In a small study of 29 patients, greater than 50% improvement in pain scores was observed with physical therapy in 59% of patients and with levator-directed trigger-point injections in 58% of patients.71 The high prevalence and severity of psychosocial issues in patients with urologic chronic pain syndromes54 underscores the need for appropriate pharmacotherapy, counseling, and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy. These are often integrated in multidisciplinary programs that incorporate physical therapy, particularly for patients whose symptoms are refractory to other approaches. However, we believe that these approaches are underutilized in clinical practice. A meta-analysis of 7 trials involving 471 patients observed that acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture in improving symptoms and QoL.72

Microwave thermotherapy or transurethral needle ablation of the prostate have limited efficacy.73 There is insufficient evidence to gauge the benefit of SNS for refractory CP/CPPS.74 There is also little evidence to support the use of other surgical techniques, even for refractory CP/CPPS75 (shown in Table 4).

Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome

Definition

The National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases workshop on IC proposed diagnostic criteria for clinical trials in 1987.76 However, these criteria are too restrictive for daily use and have been estimated to miss 60% of patients with BPS.77 In 2009, the Society for Urodynamics and Female Urology defined IC/BPS as an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms (eg, urinary frequency), of more than 6 weeks' duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes. Some patients with BPS have IC, which is characterized by symptoms of BPS and vesical abnormalities (ie, mucosal ulcerations [Hunner ulcers]), punctuate hemorrhages (glomerulations) after bladder hydrodistention, and an increased number of detrusor mast cells.78 This definition was also adopted by the updated guidelines issued by the American Urological Association in 2015.5

Epidemiology

As detailed elsewhere,5 the prevalence of IC/BPS depends on the criteria and the methods (ie, self-report, questionnaires, or administrative billing data) used to diagnose it. The most recent questionnaire-based study in US adult women reported a prevalence of 2.7% using highly specific criteria and 6.53% using highly sensitive criteria. This translates to between approximately 3.3 and 7.9 million women.79 Only 9.7% of these women had an actual diagnosis of IC/BPS. Among adult men, symptoms of IC/BPS are also common, with an estimated prevalence of 2.9% to 4.2%. Here too, the condition may be underdiagnosed.80 In that study, 1.8% of adult men had CP/CPPS and approximately 17% had both IC/BPS and CP/CPPS.80

The economic impact of IC/BPS is summarized elsewhere.5 Among a cohort of 239 patients in a managed care setting, the mean cost of IC was $6,614, including $1,572 for prescription medications and $3,463 for outpatient medical services.81,82 Nineteen percent of women with IC/BPS lost wages, with a mean annual cost of $4,216.82

Pathophysiology

Current concepts derived largely from in vitro and animal studies support the following framework (Figure 1). Normally, the urothelium is covered by a protective layer of glycosaminoglycans (eg, chondroitin sulfate, hyaluronate sodium, glycoproteins, and mucins).83 Damage to this layer may increase urothelial permeability and predispose patients to chronic diffusion of irritants across the urothelium, mast cell activation, and neurogenic inflammation. Bladder mast cells are increased by a factor of 6- to 10-fold in classical/ulcerative IC compared with a 2-fold increase in nonulcerative IC.84 Degranulation of mast cells activates capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibers that release substance P and other neuropeptides, which cause cell damage.83 Prolonged activation of mast cells and capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibers can also cause neurogenic upregulation.83 Mediators (eg, glutamate, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide) that are released from the central terminals of primary afferent fibers in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord cause central sensitization,83 resulting in hypersensitivity to nonpainful and normally painful stimuli. Peripherally, these mechanisms damage bladder muscle and cause bladder fibrosis.

The primary insult causing IC/BPS is unknown. A role for bacterial infection and autoimmunity has been proposed but is not widely accepted.83 Patients with IC reported more frequent childhood bladder infections and urinary urgency in adolescence.85 Environmental factors such as stress and certain foods and drinks (eg, alcohol, citrus fruits, coffee) can aggravate pain. Supporting a role for genetic factors, the prevalence of IC is 17 times greater in first-degree relatives of patients with IC than in the general population and is also greater in monozygotic than dizygotic twins.86,87

A case-control study observed that the diagnosis of 6 nonbladder syndromes (eg, fibromyalgia-chronic widespread pain, irritable bowel syndrome, and panic disorder) preceded the diagnosis of IC/BPS.88 These findings were broadly confirmed in a subsequent report.89 There are 3 possible explanations for such associations: 1) that the nonbladder and bladder syndromes share genetic or environmental risk factors, 2) that the syndrome is a risk factor for IC/BPS, or 3) that the syndrome and IC/BPS are different manifestations of the same pathophysiologic process or disease. Prospective studies are necessary to confirm these associations.

Clinical Features

Initially, patients with IC/BPS may report only 1 symptom such as dysuria, frequency, or pain5 (data in Table 2). Subsequently, the typical symptoms develop, such as pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort and daytime urinary frequency (>10 times) or urgency, which is due to pain, pressure, or discomfort and not due to fear of wetting. Symptoms may flare for several hours to weeks. Symptoms are similar in men and women.

Other coexistent conditions include irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety and depression, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic headache, dysmenorrhea, and vulvodynia.5 Indeed, the UPOINT system can also be used for IC/BPS.67 Women with IC undergo significantly more pelvic surgeries (eg, hysterectomy) than controls.90

IC/BPS can profoundly impair psychosocial functioning and QoL. The effect on QoL is as severe as that in rheumatoid arthritis and end-stage renal disease.5 Women with IC/BPS have significantly more pain, sleep dysfunction, catastrophizing, depression, anxiety, difficulty with social functions, and sexual dysfunction than women without IC/BPS. Sexual dysfunction is moderate to severe, secondary to the pain in IC/BPS, and is the primary predictor of poor QoL.

Physical examination may disclose tenderness of the pelvic muscles, bladder, urethra, or external genitalia; palpation-induced abdominal tenderness; pelvic asymmetry; and pelvic floor dysfunctions, which may be manifested as an inability to maintain pelvic relaxation.91,92 An occult neurologic problem and occult retention should be excluded with a neurologic examination and assessment of the postvoid residual urine volume, respectively.

Diagnostic Tests

At baseline, the intensity of pain should be evaluated with standardized instruments (eg, O'Leary-Saint ICSI/ICPI93 or a 10-pt Likert scale). At a minimum, voiding symptoms should be assessed with a 1-day voiding diary, which is as useful as a 3-day voiding diary.94 These assessments not only help establish the diagnosis but also provide a baseline against which the response to treatment can be evaluated. Alternate diagnoses should be sought in patients who have very low voiding frequencies or high voided volumes instead of a low-volume/frequent-voiding pattern. A urinary tract infection should be excluded with urinalysis and a urine culture in all patients. Urine cytology should be assessed in patients with microhematuria and in smokers, who have a greater risk of bladder cancer.5 Cystoscopy and urodynamic studies are only required if the diagnosis is in doubt or the information might guide therapy. Cystoscopy may reveal Hunner ulcers, which is an inflammatory-appearing lesion seen in IC/BPS, or glomerulations (ie, pinpoint submucosal petechial hemorrhages), which are consistent with IC/BPS but are also seen in other conditions (eg, chronic undifferentiated pelvic pain) that mimic or coexist with IC/BPS. Cystoscopy can also identify bladder cancer or stones and urethral diverticula. During cystoscopy, hydrodistention is not routinely necessary to diagnose IC/BPS. Urodynamic testing is useful in patients with suspected outlet obstruction or poor detrusor contractility and in patients who are refractory to initial therapy. Urodynamic testing may reveal pain during bladder filling and/or features of voiding dysfunction (eg, bladder outlet obstruction, detrusor overactivity, or pelvic floor dysfunction). However, there are no urodynamic features specific for IC/BPS. Assessment of permeability by measuring intravesicular potassium level is prone to false-positive and false-negative results and is not recommended for diagnosis of IC.

Differential Diagnosis

Endometriosis is also associated with pelvic pain and urinary symptoms.95 Among 1,000 patients with endometriosis, pelvic pain (68%), dysmenorrhea (79%), and dyspareunia (45%) were the most common presenting symptoms.95,96 Because the response to hormonal treatment does not reliably predict endometriosis, laparoscopy with biopsy of suspected lesions is necessary for diagnosing endometriosis.97 The abnormalities on cystoscopy described above may favor a diagnosis of IC.

Overactive bladder and IC/BPS share several symptoms (ie, urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia). Severe pelvic pain and dyspareunia suggest IC/BPS, whereas urge urinary incontinence suggests overactive bladder syndrome.95 IC/BPS should be considered in patients with symptoms of refractory overactive bladder.98 During urodynamic studies, patients with IC/BPS are more likely to have hypersensitivity and lower capacity during filling cytometry, but detrusor overactivity is more common in overactive bladder syndrome.99,100 However, these urodynamic findings do not necessarily help distinguish between these 2 diseases.

Patients with vulvodynia generally report vulvar burning and dyspareunia but not urinary symptoms.95 Coccygodynia presents as pain arising in or around the coccyx that is usually triggered by prolonged sitting on hard surfaces.101 The pain may be preceded by or associated with trauma, childbirth, or lumbar disc degeneration. Patients with coccygodynia have tenderness to palpation or manipulation of the coccyx.

Management

Patients with IC/BPS should be educated about possible underlying causes and treatment options (Table 5).102-116 Lifestyle modifications include avoiding factors that may precipitate symptoms (eg, excessive fluid intake, coffee, citrus products, sexual intercourse, and tight-fitting clothing).5 Application of local heat or cold over the bladder or perineum may also be useful.

Table 5. Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS).

| Category | Examples | Evidence strengtha | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral pharmacotherapy | |||

| Analgesics | NSAIDs | Expert opinion | Consider multimodality therapy. Avoid opioids |

| Restore epithelial barrier | Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS) | B102 | Restores epithelial permeability barrier Only oral therapy approved by the FDA |

| Mast cell stabilizers | Hydroxyzine | C103 | Main adverse effect: sedation |

| Cimetidine | B104 | Potential for drug interactions | |

| Neuromodulators | Amitriptyline | B105 | May be used in combination with PPS, hydroxyzine 106 |

| Immunosuppressants | Cyclosporine A | C107 | Reserve for refractory IC/BPS Potential for serious adverse effects |

| Intravesicular therapy | |||

| Free-radical scavenger | Dimethyl sulfoxide | C108 | Only intravesicular therapy approved by the FDA May be administered as a cocktail with heparin, sodium bicarbonate, lidocaine, and corticosteroids5 |

| Restore bladder barrier | Heparin | C109 | Infrequent and minor adverse effects in noncontrolled studies |

| Topical anesthetics | Lidocaine | C110 | Combination with sodium bicarbonate avoids ionization within urine, thereby increasing ability to penetrate uroepithelium |

| Hydrodistention of bladder | Low pressure and short duration | C111 | Generally performed with low pressure (60 to 80 cm H2O) and for a short duration (<10 min) |

| Bladder fulguration | Laser, electrocautery | C112 | Considered for Hunner ulcers |

| Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) | Intradetrusor BoNT-A injection | B113 | BoNT-A 100 U and 200 U provided comparable relief, but urinary retention was more common after 200 U114 |

| Surgery | |||

| Sacral nerve stimulation | Sacral neuromodulation (InterStim™; Medtronic) | C115 | More effective for urinary symptoms than pain |

| Bladder surgery | Substitution cystoplasty Urinary diversion with/without cystectomy |

C116 | Last resort Patients should be informed that pain may persist after surgery |

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IC/BPS, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Level A: meta-analysis of well-designed randomized controlled trials; B: at least 1 well-designed randomized controlled trial; C: at least 1 well-designed observational study; D: case series.

Thereafter, there are several options, albeit supported by variable, generally limited evidence (Table 4). Analgesics and neuromodulating agents, are recommended for alleviating pain; opioids should be avoided.5 Initial oral pharmacologic options include pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), hydroxyzine (an H1 receptor antagonist), tricyclic antidepressants, and cimetidine (an H2 receptor antagonist). PPS is a heparinlike sulfated polysaccharide that is similar to glycosaminoglycans, is purported to repair the damaged glycosaminoglycan layer lining the urothelium, and improves decreased urothelial permeability. In vitro data suggest that PPS also has anti-inflammatory effects. In randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of IC/BPS, the response rates were approximately 30% for PPS and 15% for placebo.117 PPS is the only oral medication approved for treating IC/BPS by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Systematic reviews based on limited data observed modest benefits of PPS, amitriptyline, and hydroxyzine compared with placebo. When oral therapy is insufficient, intravesical instillation with dimethyl sulfoxide (approved by the FDA), heparin, and lidocaine or cystoscopy with hydrodistention should be considered. At cystoscopy, a Hunner ulcer may be fulgurated with laser or electrocautery.

Intradetrusor administration of botulinum toxin type A inhibits the release of neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, norepinephrine, nerve growth factor, ATP, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide) from the urothelium and in nerve fibers. Botulinum toxin type A also inhibits sensory receptors in suburothelial nerve fibers.118 By inhibiting this neuroplasticity, botulinum toxin type A might reduce pain and urgency. Indeed, at 3 months, symptoms were moderately or markedly improved in 72% of patients after intradetrusor botulinum toxin type A injection (100 U) and bladder hydrodistention, compared with only 48% after hydrodistention alone, and all differences were significant; all patients were also treated with PPS.114 However, responses waned over time; by 2 years, corresponding responses were 21% and 17% for the combined group and hydrodistention alone, respectively. Bladder capacity and other cystometric variables improved with botulinum toxin and hydrodistention but not after hydrodistention alone. Cyclosporine may be beneficial in patients whose symptoms are refractory to the aforementioned approaches, especially in patients with Hunner ulcers or active bladder inflammation; however, adverse effects are common.107

Although the evidence is limited, SNS should be considered before bladder augmentation or cystectomy with urinary diversion in patients whose symptoms are refractory to medical treatment. In the largest series of 78 patients with BPS and cystoscopic evidence of glomerulation or ulcer, 44 (67%) reported significant improvement after temporary stimulation, and 41 proceeded to permanent SNS.115 With permanent SNS, 23 patients (70%) reported very good and 10 patients (30%) reported good improvement. Various reasons (eg, poor outcomes, pain) prompted explantation of the device in 20% of patients. Finally, bladder surgery may be necessary in patients with symptoms refractory to medical therapy and SNS and a small bladder.116,119,120

Conclusions

The functional anorectal and urogynecologic disorders associated with pelvic pain are defined by symptoms, along with levator tenderness (levator ani syndrome) and bladder mucosal inflammation (IC). Common to these conditions are associations with dysfunctional voiding or defecation, comorbid conditions (eg, fibromyalgia, depression), impaired QoL, and increased health care utilization. Diagnostic tests are primarily required, when appropriate, to exclude structural causes of pelvic pain. Multidisciplinary treatment approaches that integrate lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and behavioral or psychological therapy that are tailored to the symptoms should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by USPHS NIH Grant R01 DK78924 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CP/CPPS

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- IC/BPS

interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

- PPS

pentosan polysulfate sodium

- QoL

quality of life

- SNS

sacral nerve stimulation

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Bharucha reports personal fees from Allergan Inc, personal fees from Johnson and Johnson Inc, personal fees and other from Medspira, personal fees from Ironwood Pharma, personal fees from GI Care Pharma, personal fees from National Center for Pelvic Pain Research, personal fees from Salix, personal fees from Macmillan Medical Communications, personal fees from Forum Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Bharucha has patented an Anorectal manometry device with royalties paid to Medspira, Inc., and has a pending patent Anorectal manometry probe fixation device licensed to Medtronic, Inc. Dr. Lee has nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clemens JQ. Male and female pelvic pain disorders - is it all in their heads? J Urol. 2008;179:813–814. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potts JM, Payne CK. Urologic chronic pelvic pain. Pain. 2012;153(4):755–758. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Trabuco E. Functional and chronic anorectal and pelvic pain disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao S, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, et al. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.009. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanno PM, Erickson D, Moldwin R, Faraday MM. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: AUA guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193(5):1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees J, Abrahams M, Doble A, Cooper A Prostatitis Expert Reference G. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a consensus guideline. BJU International. 2015;116(4):509–525. doi: 10.1111/bju.13101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant SR, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Levator syndrome: an analysis of 316 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18(2):161–163. doi: 10.1007/BF02587168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162(2):369–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saslow SB, Thumshirn M, Camilleri M, et al. Influence of H. pylori infection on gastric motor and sensory function in asymptomatic volunteers. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 1998;43(2):258–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1018833701109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Rackley RR, Pontari MA. Clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Prostate Cancer & Prostatic Diseases. 2009;12(2):177–183. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, Whitmore KE, Spolarich-Kroll J. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A Suppl):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1510–1518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1993;38(9):1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Naudy B, Guien C, Salducci J. Manometric and radiologic investigations and biofeedback treatment of chronic idiopathic anal pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(8):690–695. doi: 10.1007/BF02050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead W. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(4):1321–1329. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey RF. Colonic motility in proctalgia fugax. Lancet. 1979;2(8145):713–714. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckardt VF, Dodt O, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Anorectal function and morphology in patients with sporadic proctalgia fugax. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(7):755–762. doi: 10.1007/BF02054440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao SS, Hatfield RA. Paroxysmal anal hyperkinesis: a characteristic feature of proctalgia fugax. Gut. 1996;39(4):609–612. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celik AF, Katsinelos P, Read NW, Khan MI, Donnelly TC. Hereditary proctalgia fugax and constipation: report of a second family. Gut. 1995;36(4):581–584. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heymen S, Wexner SD, Gulledge AD. MMPI assessment of patients with functional bowel disorders. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(6):593–596. doi: 10.1007/BF02049867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Parades V, Etienney I, Bauer P, Taouk M, Atienza P. Proctalgia fugax: demographic and clinical characteristics. What every doctor should know from a prospective study of 54 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(6):893–898. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karras JD, Angelo G. Proctalgia fugax. Clinical observations and a new diagnostic aid. Dis Colon Rectum. 1963;6:130–134. doi: 10.1007/BF02633466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson WG. Proctalgia fugax in patients with the irritable bowel, peptic ulcer, or inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(6):450–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead W. ACG Clinical Guidelines:Management of Benign Anorectal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141–1157. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Seide B, Riederer SJ, Zinsmeister AR. Phenotypic Variation in Functional Disorders of Defecation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1199–1210. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hompes R, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. What causes chronic idiopathic perineal pain? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(9):1035–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dwarkasing RS, Schouten WR, Geeraedts TE, Mitalas LE, Hop WC, Krestin GP. Chronic anal and perianal pain resolved with MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(5):1034–1041. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao SSC, Paulson J, Mata M, Zimmerman B. Clinical trial: effects of botulinum toxin on Levator ani syndrome--a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Alimentary Pharmacol Therapeut. 2009;29(9):985–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodi G, Bogoni F, Infantino A, Pianon P, Mortellaro LM, Lise M. Hot or cold in anal pain? A study of the changes in internal anal sphincter pressure profiles. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(4):248–251. doi: 10.1007/BF02553028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkin GK, Suliman A, Vaizey CJ. Patient characteristics and treatment outcome in functional anorectal pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(7):870–875. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318217586f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falletto E, Masin A, Lolli P, et al. Is sacral nerve stimulation an effective treatment for chronic idiopathic anal pain? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(3):456–462. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819d1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govaert B, Melenhorst J, van Kleef M, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of chronic functional anorectal pain: a single center experience. Pain Pract. 2010;10(1):49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dudding TC, Thomas GP, Hollingshead JR, George AT, Stern J, Vaizey CJ. Sacral nerve stimulation: an effective treatment for chronic functional anal pain? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(9):1140–1144. doi: 10.1111/codi.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rome JD, Sletten CD, Bruce BK. A rehabilitation approach to chronic pain in rheumatologic practice. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8(2):163–168. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rome JD, Townsend CO, Bruce BK, Sletten CD, Luedtke CA, Hodgson JE. Chronic noncancer pain rehabilitation with opioid withdrawal: comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(6):759–768. doi: 10.4065/79.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckardt VF, Dodt O, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Treatment of proctalgia fugax with salbutamol inhalation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(4):686–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, Clark J. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol. 2001;165(3):842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Low agreement between previous physician diagnosed prostatitis and national institutes of health chronic prostatitis symptom index pain measures. J Urol. 2004;171(1):279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000100088.70887.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, Brensinger CM, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Landis JR. A prospective study of interstitial cystitis: results of longitudinal followup of the interstitial cystitis data base cohort. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study Group.[see comment] J Urol. 2000;163(5):1434–1439. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolcott RD, Ehrlich GD. Biofilms and chronic infections. JAMA. 2008;299(22):2682–2684. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.22.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickel JC, Stephens A, Landis JR, et al. Search for Microorganisms in Men with Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Culture-Independent Analysis in the MAPP Research Network. J Urol. 2015;194(1):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pontari M, Giusto L. New developments in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23(6):565–569. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283656a55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.True LD, Berger RE, Rothman I, Ross SO, Krieger JN. Prostate histopathology and the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective biopsy study.[see comment] J Urol. 1999;162(6):2014–2018. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nickel JC, Roehrborn CG, O'Leary MP, Bostwick DG, Somerville MC, Rittmaster RS. The relationship between prostate inflammation and lower urinary tract symptoms: examination of baseline data from the REDUCE trial. Eur Urol. 2008;54(6):1379–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe T, Inoue M, Sasaki K, et al. Nerve growth factor level in the prostatic fluid of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is correlated with symptom severity and response to treatment. BJU International. 2011;108(2):248–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Done JD, Rudick CN, Quick ML, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P. Role of mast cells in male chronic pelvic pain. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1473–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pontari MA, Ruggieri MR. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179(5 Suppl):S61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehik A, Hellstrom P, Sarpola A, Lukkarinen O, Jarvelin MR. Fears, sexual disturbances and personality features in men with prostatitis: a population-based cross-sectional study in Finland. BJU International. 2001;88(1):35–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Chan CA, Morey A, Flores V. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179(3):956–960. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X, Zhou Z, Qiu X, Wang B, Dai J. The Effect of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS) on Erectile Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2015;10(10):e0141447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Afari N, et al. Widespread Psychosocial Difficulties in Men and Women With Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes: Case-control Findings From the Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network. Urology. 2015;85(6):1319–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wenninger K, Heiman JR, Rothman I, Berghuis JP, Berger RE. Sickness impact of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and its correlates. J Urol. 1996;155(3):965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pontari MA, McNaughton-Collins M, O'Leary MP, et al. A case-control study of risk factors in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU International. 2005;96(4):559–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nickel JC, Shoskes D, Wang Y, et al. How does the pre-massage and post-massage 2-glass test compare to the Meares-Stamey 4-glass test in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome? J Urol. 2006;176(1):119–124. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00498-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moghaddasi M, Aghaii M, Mamarabadi M. Perianal pain as a presentation of lumbosacral neurofibroma: a case report. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014;75(2):e191–193. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elist J. Effects of pollen extract preparation Prostat/Poltit on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Urology. 2006;67(1):60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao WP, Zhang ZG, Li XD, et al. Celecoxib reduces symptoms in men with difficult chronic pelvic pain syndrome (Category IIIA) Brazil J Med Biol Res. 2009;42(10):963–967. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009005000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pontari MA, Krieger JN, Litwin MS, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Int Med. 2010;170(17):1586–1593. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaplan SA, Volpe MA, Te AE. A prospective, 1-year trial using saw palmetto versus finasteride in the treatment of category III prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2004;171(1):284–288. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000101487.83730.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kong do H, Yun CJ, Park HJ, Park NC. The efficacy of mirodenafil for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in middle-aged males. World J Mens Health. 2014;32(3):145–150. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clemens JQ, Nadler RB, Schaeffer AJ, Belani J, Albaugh J, Bushman W. Biofeedback, pelvic floor re-education, and bladder training for male chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2000;56(6):951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00796-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tirlapur SA, Vlismas A, Ball E, Khan KS. Nerve stimulation for chronic pelvic pain and bladder pain syndrome: a systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2013;92(8):881–887. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chiang PH, Chiang CP. Therapeutic effect of transurethral needle ablation in non-bacterial prostatitis: chronic pelvic pain syndrome type IIIa. Int J Urol. 2004;11(2):97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kartha GK, Kerr H, Shoskes DA. Clinical phenotyping of urologic pain patients. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23(6):560–564. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283652a9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Kattan MW. Phenotypically directed multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study using UPOINT. Urology. 2010;75(6):1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anothaisintawee T, Attia J, Nickel JC, et al. Management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(1):78–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA. Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training. J Urol. 2006;176(4 Pt 1):1534–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010. discussion 1538-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zoorob D, South M, Karram M, et al. A pilot randomized trial of levator injections versus physical therapy for treatment of pelvic floor myalgia and sexual pain. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2015;26(6):845–852. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin Z, Wu J, Zhou J, Liu Z. Systematic Review of Acupuncture for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Medicine. 2016;95(11):e3095. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeitlin SI. Heat therapy in the treatment of prostatitis. Urology. 2002;60(6 Suppl):38–40. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02385-3. discussion 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marcelissen T, Jacobs R, van Kerrebroeck P, de Wachter S. Sacral neuromodulation as a treatment for chronic pelvic pain. J Urol. 2011;186(2):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nickel JC. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gillenwater JY, Wein AJ. Summary of the National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases Workshop on Interstitial Cystitis, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, August 28-29, 1987. J Urol. 1988;140(1):203–206. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hanno PM, Landis JR, Matthews-Cook Y, Kusek J, Nyberg L., Jr The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. J Urol. 1999;161(2):553–557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)61948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanno P, Dmochowski R. Status of international consensus on interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome/painful bladder syndrome: 2008 snapshot. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(4):274–286. doi: 10.1002/nau.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186(2):540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA, Elliott MN, Suttorp MJ, Clemens JQ. The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology male study. J Urol. 2013;189(1):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MC, Kimes T, Calhoun EA. Costs of interstitial cystitis in a managed care population. Urology. 2008;71(5):776–780. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.154. discussion 780-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clemens JQ, Markossian T, Calhoun EA. Comparison of economic impact of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2009;73(4):743–746. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grover S, Srivastava A, Lee R, Tewari AK, Te AE. Role of inflammation in bladder function and interstitial cystitis. Ther Adv Urol. 2011;3(1):19–33. doi: 10.1177/1756287211398255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peeker R, Enerback L, Fall M, Aldenborg F. Recruitment, distribution and phenotypes of mast cells in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2000;163(3):1009–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peters KM, Killinger KA, Ibrahim IA. Childhood symptoms and events in women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2009;73(2):258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Warren JW, Keay SK, Meyers D, Xu J. Concordance of interstitial cystitis in monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs. Urology. 2001;57(6 Suppl 1):22–25. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Warren JW, Jackson TL, Langenberg P, Meyers DJ, Xu J. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in first-degree relatives of patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2004;63(1):17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Warren JW, Howard FM, Cross RK, et al. Antecedent nonbladder syndromes in case-control study of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2009;73(1):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Warren JW, Wesselmann U, Morozov V, Langenberg PW. Numbers and types of nonbladder syndromes as risk factors for interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2011;77(2):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ingber M, Peters K, Killinger K, Carrico D, Ibrahim I, Diokno A. Dilemmas in diagnosing pelvic pain: multiple pelvic surgeries common in women with interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Kalinowski SE, Ibrahim IA, Diokno AC. Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;70(1):16–18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tu FF, Holt JJ, Gonzales J, Fitzgerald CM. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):272.e271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sirinian E, Azevedo K, Payne CK. Correlation between 2 interstitial cystitis symptom instruments. J Urol. 2005;173(3):835–840. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152672.83393.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazurick CA, Landis JR. Evaluation of repeat daily voiding measures in the National Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study. J Urol. 2000;163(4):1208–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. J Urol. 2007;177(2):450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.032. [see comment][erratum appears in J Urol. 2007 Jun;177(6):2402] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sinaii N, Plumb K, Cotton L, et al. Differences in characteristics among 1,000 women with endometriosis based on extent of disease. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(3):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jenkins TR, Liu CY, White J. Does response to hormonal therapy predict presence or absence of endometriosis? J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Macdiarmid SA, Sand PK. Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/ painful bladder syndrome in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Rev Urol. 2007;9(1):9–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim SH, Kim TB, Kim SW, Oh SJ. Urodynamic findings of the painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a comparison with idiopathic overactive bladder. J Urol. 2009;181(6):2550–2554. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kirkemo A, Peabody M, Diokno AC, et al. Associations among urodynamic findings and symptoms in women enrolled in the Interstitial Cystitis Data Base (ICDB) Study. Urology. 1997;49(5A Suppl):76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014;14(1):84–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dimitrakov J, Kroenke K, Steers WD, et al. Pharmacologic management of painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(18):1922–1929. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sant GR, Propert KJ, Hanno PM, et al. A pilot clinical trial of oral pentosan polysulfate and oral hydroxyzine in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2003;170(3):810–815. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000083020.06212.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thilagarajah R, Witherow RO, Walker MM. Oral cimetidine gives effective symptom relief in painful bladder disease: a prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. BJU International. 2001;87(3):207–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van Ophoven A, Pokupic S, Heinecke A, Hertle L. A prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind study of amitriptyline for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004;172(2):533–536. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132388.54703.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moldwin RM, Evans RJ, Stanford EJ, Rosenberg MT. Rational approaches to the treatment of patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69(4 Suppl):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Forrest JB, Payne CK, Erickson DR. Cyclosporine A for refractory interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: experience of 3 tertiary centers. J Urol. 2012;188(4):1186–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Perez-Marrero R, Emerson LE, Feltis JT. A controlled study of dimethyl sulfoxide in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1988;140(1):36–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Parsons CL, Housley T, Schmidt JD, Lebow D. Treatment of interstitial cystitis with intravesical heparin. Br J Urol. 1994;73(5):504–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Proctor J, et al. Alkalinized lidocaine and heparin provide immediate relief of pain and urgency in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aihara K, Hirayama A, Tanaka N, Fujimoto K, Yoshida K, Hirao Y. Hydrodistension under local anesthesia for patients with suspected painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: safety, diagnostic potential and therapeutic efficacy. Int J Urol. 2009;16(12):947–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rofeim O, Hom D, Freid RM, Moldwin RM. Use of the neodymium: YAG laser for interstitial cystitis: a prospective study. J Urol. 2001;166(1):134–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pinto R, Lopes T, Frias B, et al. Trigonal injection of botulinum toxin A in patients with refractory bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Eur Urol. 2010;58(3):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kuo HC, Chancellor MB. Comparison of intravesical botulinum toxin type A injections plus hydrodistention with hydrodistention alone for the treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. BJU Int. 2009;104(5):657–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gajewski JB, Al-Zahrani AA. The long-term efficacy of sacral neuromodulation in the management of intractable cases of bladder pain syndrome: 14 years of experience in one centre. BJU Int. 2011;107(8):1258–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peeker R, Aldenborg F, Fall M. The treatment of interstitial cystitis with supratrigonal cystectomy and ileocystoplasty: difference in outcome between classic and nonulcer disease. J Urol. 1998;159(5):1479–1482. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hwang P, Auclair B, Beechinor D, Diment M, Einarson TR. Efficacy of pentosan polysulfate in the treatment of interstitial cystitis: a meta-analysis. Urology. 1997;50(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Apostolidis A, Popat R, Yiangou Y, et al. Decreased sensory receptors P2X3 and TRPV1 in suburothelial nerve fibers following intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin for human detrusor overactivity. J Urol. 2005;174(3):977–982. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169481.42259.54. discussion 982-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nielsen KK, Kromann-Andersen B, Steven K, Hald T. Failure of combined supratrigonal cystectomy and Mainz ileocecocystoplasty in intractable interstitial cystitis: is histology and mast cell count a reliable predictor for the outcome of surgery? J Urol. 1990;144(2 Pt 1):255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39426-0. discussion 258-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rossberger J, Fall M, Jonsson O, Peeker R. Long-term results of reconstructive surgery in patients with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: subtyping is imperative. Urology. 2007;70(4):638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]