Abstract

Background

Increased sympathetic outflow is a major contributor to the progression of chronic heart failure (CHF). Potentiation of glutamatergic tone has been causally related to the sympathoexcitation in CHF. Specifically, an increase in the N-methyl-D-aspartate-type1 receptor (NMDA-NR1) expression within the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) is critically linked to the increased sympathoexcitation during CHF. However, the molecular mechanism(s) for the up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 remains unexplored. We hypothesized that hypoxia via HIF-1α might contribute to the augmentation of the NMDA-NR1 mediated sympathoexcitatory responses from the PVN in CHF.

Methods and Results

Immunohistochemistry staining, mRNA, and protein for hypoxia-inducible-factor 1α (HIF-1α) were up-regulated within the PVN of left coronary artery ligated CHF rats. In neuronal cell line (NG108-15) in vitro, hypoxia caused a significant increase in mRNA as well as protein for HIF-1α (2-fold) with the concomitant increase in NMDA-NR1 mRNA, protein levels, as well as glutamate-induced Ca+ influx. ChIP assay identified HIF-1α binding to NMDA-NR1 promoter during hypoxia. Silencing of HIF-1α in NG108 cells leads to a significant decrease in expression of NMDA-NR1 suggesting that expression of HIF-1α is necessary for the upregulation of NMDA-NR1. Consistent with these observations, HIF-1α silencing within the PVN abrogated the increased basal sympathetic tone as well as sympathoexcitatory responses to microinjection of NMDA in the PVN of rats with CHF.

Conclusions

These results uncover a critical role for HIF-1 in the up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 to mediate sympathoexcitation in CHF. We conclude that subtle hypoxia within the PVN may act as a metabolic cue to modulate sympathoexcitation during CHF.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), sympatho-excitation, brain, autonomic nervous system, paraventricular nucleus, NMDA-NR1

During chronic heart failure (CHF) blood supply to the brain may be compromised. A relative or imperceptibly subtle change of blood flow to specific brain area may result in an oxygen deficiency, possibly characterized as a mild hypoxic state. Hypoxia is known to induce changes at the molecular level within cells. The first adaptive cellular response to hypoxia involves the upregulation and stabilization of hypoxia-inducible-factor-1 (HIF-1), a major transcription factor involved in gene regulation under low oxygen environment. HIF-1 is a heterodimer of HIF-1α and HIF-1β subunits. In physiological conditions, the HIF-1β subunit is constitutively expressed, and the HIF-1α subunit is present at relatively low levels because of continuous proteolysis through an oxygen-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway 1. HIF-1α is subjected to hydroxylation on proline residues via prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) enzyme under normoxic conditions. Hydroxylation is a prerequisite for the binding of the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) tumor suppressor protein, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, which targets HIF-1α for proteasomal degradation. Under hypoxic conditions, PHD catalytic activity is inhibited, and the pVHL protein does not bind to HIF-1α, ultimately leading to stabilization of the alpha-subunit. Once stabilized, this heterodimer of HIF-1α and HIF-1β, translocate to the nucleus and is capable of binding to hypoxia response elements (HRE) in promoter sequences of genes involved in angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, glycolysis, iron metabolism, and cell survival 2.

Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the brain is vital for cardiovascular regulation 3, 4 and is responsive to hypoxic stress 5. Neurons within the PVN are regulated by glutamate, as an excitatory neurotransmitter 6, and nitric oxide 7, 8, as an inhibitory regulator. Disturbances in these homeostatic mechanisms can alter the sympathetic tone and are exasperated in disease conditions such as hypertension and CHF 7, 9. It has been shown that during CHF an increase in glutamatergic activity via an upregulation of the NMDA(N-methyl-D-aspartate-type)-NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor, at transcriptional as well as translational level, plays an important role in increasing the sympathoexcitation6. NMDARs are hetero-oligomeric proteins and are composed of the essential NMDA-NR1 structural subunit, NR2 subunits (A-D) and NR3 subunit (A-B) 10–12. Incorporation of NR2 subunit depends on the age and region of brain 11, 13. NR3 subunit functions as a negative modulator of the receptor 12, 14. Over-activation of NMDAR can result in neuronal excitotoxicity and neuronal cell death due to intracellular accumulation of calcium leading to brain injury and possible chronic neurodegenerative disorder. The molecular mechanism responsible for this upregulation of NMDA-NR1 remains unclear. NMDARs are subjected to multiple levels of regulation including transcriptional 10 as well as post-transcriptional, involving phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by kinase and phosphatases 15. Being an obligatory subunit of NMDAR, the molecular mechanisms of NMDA-NR1 subunit regulation are fundamental to receptor function. We hypothesize that the HIF-1 transcriptional complex accumulation may be regulating/modulating the function of NMDAR in CHF. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to investigate the effect of HIF-1α stabilization on NMDA- NR1 expression in CHF.

Methods

Chronic heart failure model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 220 to 240g were fed and housed according to approved guidelines of the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Eighth Edition (National Academic Press; 2011). Rats were randomly assigned to either the Sham-operated group or the CHF group, and were ventilated at a rate of 60 breaths/min with 2–3% isoflurane during the surgical procedure. CHF was induced by ligation of the left coronary artery, which has been described previously 8 and is extensively used in our laboratory 16–19 This myocardial infarct model mimics the most common cause of CHF in humans. Left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure were assessed using hemodynamic and anatomic criteria. Rats with elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP; >15mmHg), infarct size (>35% of total left ventricle wall), significant reductions in dp/dt max were considered to be in CHF (Table). Experiments were performed on the rats 6–8 weeks after the coronary artery ligations.

Table.

Morphological and hemodynamic characteristics of Sham and CHF rats.

| Sham (n = 6) | CHF (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight(g) | 375± 2.10 | 405± 5.74 |

| Heart weight(g) | 1.2± 0.07 | 2± 0.05* |

| Infarct size (% of left ventricle) | 0 | 40 ± 1.6* |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 2.8± 0.3 | 26 ± 2.8* |

| Basal MAP (mmHg) | 92 ± 5.1 | 107 ± 4.0 |

| Basal HR (bpm) | 296± 8.2 | 321 ± 9.5 |

| Basal RSNA(μV.s) | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 1.3* |

Characteristics of Sham and CHF rats used in the studies. LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate. Data are represented as mean ± SE of 6–7 animals in each group.

Heart weight P =0.001 vs. Sham,

Infarct size P =0.001 vs. Sham,

LVEDP P =0.005 vs. Sham,

Basal RSNA P =0.039 vs. Sham.

Immunohistochemistry staining for HIF-1α in sections of the PVN

Immunohistochemistry was performed for HIF-1α in coronal sections of the PVN from Sham and CHF groups. Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (65 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with 150 ml heparinized saline followed by 250 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer. The post fixing of brains were done in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4°C for 4h followed by 20% sucrose. The brain was blocked in the coronal plane, and 10 μm sections were cut using a cryostat, mounted on slides and subjected to immunofluorescence (see data supplement for details).

Real-time PCR and Western blotting for HIF-1α in the PVN

After sacrifice, the brain was removed and quickly frozen on dry ice. Six serial coronal sections (100 μm) were cut using a cryostat, and following the Palkovits 20 technique, the PVN was bilaterally punched using a diethylpyrocarbonate-treated blunt 18-gauge needle attached to a syringe and processed as described previously8(see data supplement for details).

Induction of Hypoxia in NG108 cells

We followed the modified protocol of Wright and Shay 21 to create hypoxia in cultured NG108 cells (see data supplement for details).

Intracellular calcium concentration changes to glutamate

Sub-confluent NG108 cells were grown on Nunc Lab-Tek chambers and were exposed to hypoxia for 12h before experimentation. Glutamate-stimulated changes in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in NG108 cells were assessed by using fluo-3 (Invitrogen) fluorescence imaging using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (see data supplement for details).

siRNA knockdown of HIF-1α

siRNA targeting HIF-1α(sc-45919), a negative control siRNA (sc-37007) was purchased from Santa Cruz. Biotechnology, Inc. Transient transfection was performed in NG108 cells (2 × 105 cells) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer instructions and detailed in data supplement.

Chromatin immuno-precipitation assay (ChiP) to confirm HIF-1 binding to NMDA-NR1

The ChiP assay was performed in NG108 cells after 4h of hypoxia because at this point NMDA-NR1 mRNA starts showing an increase (see data supplement for details).

Other Measurements and Analyses

Methods for real-time PCR, western blot and Immunofluorescent microscopy of NG108-15 cells are described previously 22 (see data supplement for details).

In vivo HIF-1α siRNA transfer

In vivo HIF-1α siRNA transfer was performed according to the method described by Chen et al 23, 50pmol of HIF-1α siRNA (Santa Cruz, sc-45919) was diluted with the same volume of Lipofectamine 2000 and incubated for 45 min at room temperature (25 °C). HIF-1α siRNA-lipid complexes (200nl) were injected bilaterally into the PVN using a Hamilton micro-syringe under a guidance of stereotaxic instrument (Kent Scientific Corporation) in anesthetized rats.

Hemodynamic and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) measurements

Rats were anesthetized with urethane (0.75 g/kg IP) and α-chloralose (70 mg/kg IP). RSNA was monitored in the four groups of rats Sham, CHF, Sham+HIF-1α siRNA and CHF+ HIF-1α siRNA after 6–8h of injection as described before 6, 8, 18, 19 and greater details are provided in the data supplement.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups and among groups were assessed by t-test (with and without Welch correction), one or two-way ANOVA followed by Holm Sidak’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analysis of significance (Prism 7; GraphPad Software). Additional specific details are provided in the data supplement. P < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Expression of HIF-1α in the PVN during CHF

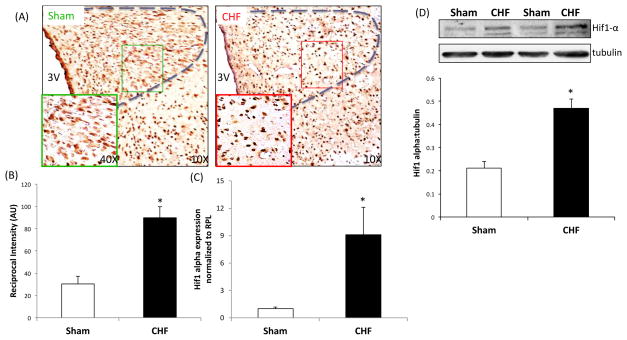

Immunohistochemistry staining for HIF-1α expression in the PVN from a Sham and CHF rat are shown in Figure 1A. HIF-1α positive staining was observed in the parvocellular as well as the magnocellular regions of the PVN. There was a distinct upregulation of HIF-1α immunolabeling in the PVN sections from CHF rats compared to Sham rats. Quantification of reciprocal intensity 24 as mentioned above revealed that there was a significant increase in DAB staining in the PVN of CHF rats suggesting an increase in HIF-1α expression. Figure 1B shows that HIF-1α mRNA levels (normalized to levels of RPL) were elevated approximately nine-fold in the PVN of CHF rats relative to the Sham rats. Furthermore, western blotting for HIF-1α in the PVN punches corroborates our immunohistochemistry results showing a 2.4-fold upregulation of HIF-1α in CHF compared to Sham (0.18±0.03 vs. 0.43±0.01*) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

HIF-1α expression in the PVN in CHF. (A) Immunohistochemistry of PVN sections from Sham and CHF rats. Representative pictures a: lower magnification; b: higher magnification and average values obtained by the reciprocal intensity method in each group were shown. Values are mean±SEM of analyses of 3 animals in each group. *P=0.004 vs. Sham. (B) HIF-1α mRNA expression relative to rpl19 in punched PVN samples measured by real-time PCR in the PVN in CHF rats. Changes in HIF-1α mRNA are presented in folds with reference to the Sham group. Values are mean±SEM of quadruplicate analyses on 4–5 animals in each group. *P =0.014 vs. Sham. (C) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α in the PVN punches from Sham and CHF rats. Top: a representative western blot, bottom: densitometry analyses of HIF-1α level normalized to tubulin. Values are mean±SEM of quadruplicate analyses on 4–5 animals in each group. *P =0.001 vs. Sham.

Changes in HIF-1α expression in response to hypoxia in NG108 cells

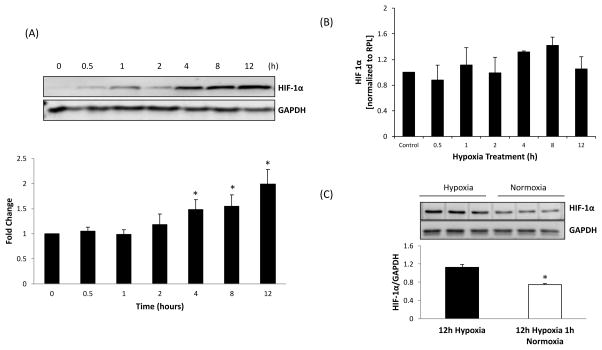

To understand the effect of hypoxia on HIF-1α expression, NG108 cells were challenged to hypoxia. Figure 2A shows that after 2h of hypoxia, HIF-1α protein levels (normalized to GAPDH) started to increase, however, we did not observe a statistically significant increase in 4 h (1.48±0.19-fold change), with a continual increase at 8 and 12 h (1.55±0.22 and 1.99±. 28 fold changes, respectively). No significant differences were observed between HIF-1α mRNA levels in control and hypoxic cells up to 2h (Figure 2B). However, transient but not significant increases of 32 and 42% were observed at 4h and 8h followed by a decrease at 12h, suggesting that hypoxia does not have any significant effect on mRNA of HIf-1α. It is possible that the control of HIF-1α expression in the NG108 cells is principally posttranscriptional, most likely at the level of protein degradation. Figure 2C shows that 1 h of normoxia following 12 h of hypoxia significantly reduces the levels of HIF-1α, suggesting the reversibility and a role for oxygen-sensing machinery in the regulation of HIF-1α.

Figure 2.

Hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression in NG108 cells. (A) Western blot analysis was used to assess levels of HIF-1α protein after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours of exposure to hypoxia. Top: a representative western blot, bottom: densitometry analyses of HIF-1α level normalized to GAPDH. *P =0.035 4h vs. 0 h control, *P =0.003 8h vs. 0 h control. *P =0.013 12h vs. 0 h control, (B) RT-PCR of HIF-1α relative to rpl19 after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours of exposure to hypoxia. *P =0.051 4h vs. 0 h control, *P =0.011 8h vs. 0 h control, P =0.023 12h vs. 0 h control, P =0.001 24h vs. 0 h control (C) HIF-1α protein expression after normoxia in hypoxia samples. Protein levels of HIF-1α were measured in NG108 cells after 12 hours of hypoxia and after 12 hours of hypoxia followed by 1 hour of normoxia Top: a representative western blot, bottom: densitometry analyses of HIF-1α level normalized to GAPDH. *P=0.002 Compared to 12 h of hypoxia. Values were mean±SE from four Independent experiments.

Changes in NMDA-NR1 expression to hypoxia in NG108 cells

The NMDA-NR1 promoter sequence has at least one known HIF-1 transcription complex binding site25. This suggests that the HIF-1 transcription complex may bind to the NMDA-NR1 promoter and increase transcription of NMDA-NR1. Our real-time PCR analysis revealed that after half an hour of hypoxia, NMDA-NR1 levels were elevated approximately two-fold relative to the control (Figure 3A). A statistically significant increase was observed at hypoxic time points of 4, 8 and 12 h and after that, it started to decrease. In accord with changes in mRNA, protein expression of NMDA-NR1 subunit started to increase at 4h and reached statistically significant level after 12 h of hypoxia exposure (1.42±0.23-fold change) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Hypoxia-induced NMDAR-NR1 expression in NG108 cells. (A) Western blot analysis was used to assess levels of NMDAR-NR1 present after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours of exposure to hypoxia. Top: a representative western blot, bottom: densitometry analyses of NMDAR-NR1 level normalized to GAPDH. *P =0.035 4h vs. 0 h control (B) RT-PCR of NMDAR-NR1 relative to rpl19 after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours of exposure to hypoxia. *P =0.035 4h vs. 0 h control, *P<0.05 Compared to 0 h control. Values were mean±SE from four Independent experiments. (C) Immunofluorescent staining for HIF-1α and NMDAR-NR1 after 12 hours of hypoxia exposure in NG108 cells. Representative images of NG108 cells before and after hypoxia exposure are presented. NMDA-NR1 (green), HIF-1α (red), and Nuclei (blue).

Immunofluorescent staining of HIF-1α and NMDA-NR1 in NG108 cells

To further corroborate these expression data, we stained NG108 cells for HIF-1α and NMDA-NR1 after 0 and 12 h of hypoxia (Figure 3C). Representative micrograph of stained neurons revealed an increase in both HIF-1α and NMDA-NR1 expression after 12h of hypoxia. Very weak immunofluorescence of HIF-1α was detected in the cytoplasm of NG108 cells grown in normoxia, however, upon hypoxic exposure, there was a dramatic increase in HIF-1α levels that was observed to translocate to the nucleus. In the merged high magnification image, HIF-1α was clearly identified in nucleus stained in dark pink. Similar to HIF-1α, NMDA-NR1 immunostaining was also increased in response to hypoxia (Figure 3D).

Functional responses of activating NMDAR after hypoxia in NG108 cells

To assess the functional significance of changes in expression of NMDAR during hypoxia, glutamate-stimulated NMDAR mediated increase in intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i influx) was monitored in NG108 cells that were exposed to hypoxia for 12h using Fura 2 confocal live cell imaging technique 26., 27 (Figure 4). This 12h time point was chosen for Ca2+ measurement since a maximum increase in HIF-1α expression occurred at this time. Stimulation with glutamate (10 μM) increased the intensity of Ca2+ staining in control as well as hypoxia exposed group of cells (Figure 4A) However, quantitative analysis of cell images showed that, cells exposed to hypoxia demonstrated augmented increase in [Ca2+]i compared to control cells (Figure 4B), suggesting an improved functional response to glutamate via NMDAR in hypoxic cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative pictures of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) as measured by Fura 2 in response to glutamate in hypoxic NG108 cells (B) A representative of time series of live cell confocal imaging of single cell from each group after glutamate stimulation (C) Cumulative data of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) represented as arbitrary intensity units of control and hypoxia group at basal and after glutamate stimulation at 42 sec which is the time point showing maximum Fura 2 intensity in most of the neurons (n = 20–22 cells from three cover slips in each group). *P=0.001 after glutamate stimulation compared to basal levels in control group. *P=0.001 after glutamate stimulation compared to basal levels in hypoxia group. #P=0.003 after glutamate stimulation hypoxic group vs. control group.

HIF-1α regulates NMDA-NR1 receptors in NG108 cells

To further test the hypothesis that HIF-1 transcription factor may be regulating NMDA-NR1 upregulation, we used two approaches: 1) ChIP assay and 2) siRNA-mediated targeting of HIF-1α. ChIP assay revealed that compared with the control, the binding of HIF-1 transcription complex to NMDA-NR1 promoter was increased 3.2-fold in cells exposed to 4h of hypoxia (Figure 5A). Next, NG108 cells were transfected with either HIF-1α-siRNA or with a scrambled siRNA. Four pmol of siRNA showed a slight but not significant decrease in HIF-1α and NMDA-NR1 protein levels compared to the scrambled siRNA while 8 pmol of siRNA showed approximately 57% decrease in HIF-1α protein expression and a 64% decrease in NMDA-NR1 protein expression compared to the scrambled siRNA suggesting a potential role for HIF-1α in the regulation of NR1 subunit (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) ChIP assay of NG108 cells exposed to hypoxia using HIF-1α antibody and IgG as the control. Top: a representative agarose gel, bottom: densitometry analyses of NMDA-NR1 promoter fragment levels normalized to input. Values were mean±SE from three Independent experiments. *P=0.010 Compared to 0 h control. (B) HIF-1α and NMDAR-NR1 expression after siRNA HIF-1α knockdown. Top: a representative western blot, bottom: densitometry analyses of HIF-1α and level normalized to GAPDH. *P=0.030 HIF-1α, *P=0.036 NMDA-NR1 Compared to scramble siRNA. Values were mean±SE from four Independent experiments.

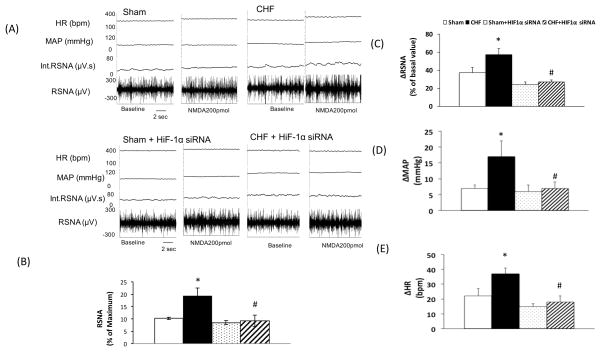

NMDA-mediated sympathoexcitatory responses from the PVN after silencing HIF-1α

To translate our in vitro findings to whole animal functional studies, we assessed the effects of in vivo HIF-1α silencing on NMDAR mediated sympathoexcitation from the PVN. RSNA, MAP, and HR were recorded after siRNA HIF-1α microinjection in the PVN (Figure 6). Typical tracings of the RSNA, MAP, and HR responses to the administration of NMDA (200 pmol) into the PVN in the four groups of rats (Sham, Sham+ HIF-1α siRNA, CHF, CHF+ HIF-1α siRNA) are shown in Figure 6A. Basal (calculated as the absolute value or as the percent of maximum change) 28, 29 was significantly higher in CHF rats compared to the Sham rats (Figure 6B). Silencing of HIF-1α significantly reduced baseline RSNA in rats with CHF suggesting that there is a tonic effect of elevated levels of HIF-1α to increased sympathetic tone in rats with CHF. As reported earlier RSNA, MAP, and HR responses to microinjection of NMDA into the PVN were significantly augmented in CHF rats as compared to Sham rats (RSNA: 57.4±5.3 vs. 36.7±3.8, MAP: 17.1±4.7 vs. 6.6±1.1 mmHg, and HR: 36.7±3.1 vs. 21.7±6.5 beats/min, P < 0.05). Further, silencing of HIF-1α also significantly attenuate the enhanced RSNA, MAP, and HR responses to NMDA in rats with CHF+HIF-1α group compared to CHF (RSNA: 26.9±1.3 vs. 57.4±5.3, MAP: 7.4±1.3 vs. 17.1±4.7 mmHg, and HR: 18.2±3.3 vs. 36.7±3.1 beats/min, P < 0.05) (Figure 6 C, D, E) suggesting the increased expression of HIF-1α in CHF rats may have stimulatory effect on NMDAR mediated functional responses. The vehicle control (100 nl artificial cerebrospinal fluid) microinjected into the PVN had no effects on RSNA, MAP, and HR.

Figure 6.

Renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) responses to NMDA injected into the PVN. (A) A segment of an original recording from an individual rat demonstrating the baseline parameters and peak changes in RSNA, integrated RSNA, MAP, and HR by administration of 200 pmol of NMDA into the PVN in the four groups: Sham, CHF, Sham+ siRNA + HIF-1α and CHF+ HIF-1α. (B) Mean data of baseline RSNA calculated as the percent of the maximum RSNA. *P=0.009 vs. Sham. (C) Mean data of changes in RSNA *P=0.006 vs. Sham, #P=0.002 vs. CHF (D), MAP *P=0.030 vs. Sham, #P=0.040 vs. CHF (E) HR *P=0.035 vs. Sham, #P=0.001 vs. CHF following 200 pmol of NMDA into the PVN of the four groups. Values represent mean±SE of 5–6 animals in each group.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that there was an increased expression of HIF-1α, a transcriptional regulator of the cellular adaptation to hypoxia, within the PVN of rats with CHF. We also showed that, in neuronal cells exposed to hypoxia, HIF-1α and NMDA-NR1 subunit of NMDAR are concomitantly upregulated. This increase in NMDA-NR1 expression was shown to be functionally effective as there was an increase in NMDAR mediated intracellular calcium in neuronal cells exposed to hypoxia. Conversely, HIF-1α silencing in neuronal cells decreased the expression of NMDA-NR1 subunit. Translating this to the whole animal studies, we showed that HIF-1α siRNA knockdown within the PVN of rats with CHF abrogated the enhanced basal renal sympathetic tone in rats with CHF. Furthermore, HIF-1α siRNA administration into the PVN ameliorated the increased RSNA, MAP, and HR responses to NMDA in rats with CHF. The HIF proteins are among the most rapidly degrading proteins ever studied. The half-life of HIF-1α protein is about 5–8 min under normal oxygenated conditions 30 Rapid uptake of siRNA (saturated at 1h) was reported in primary culture from hippocampus 31 leading to reduction in target mRNA levels. We believe, localized HIF1-α siRNA delivery to the PVN decreases the fresh transcription of HIF1-α while the existing cytoplasmic pool of the HIF1-α is removed by proteasomal degradation resulting in faster depletion of HIF1-α. This suggests that there is, although a subtle, but significant effect of hypoxia within specific sites such as the PVN, such that, a hypoxic environment for neurons stabilizes HIF-1α, which binds to constitutively expressed HIF-1β to form the HIF-1 transcription complex. This transcription complex then promotes transcription of NMDA-NR1 leading to increased protein expression, which leads to enhanced tonic effects of glutamatergic activation of preautonomic neurons within the PVN to cause enhanced sympathetic activity in CHF (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed model for the transcriptional up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 by HIF-1 in the PVN in CHF. Hypoxia induces upregulation of HIF-1α, which binds to constitutively expressed HIF-1β to form the HIF-1 transcription complex. This transcription complex binds to the HRE1 and HRE2 located in the promoter of NMDA-NR1 leading to increased expression of NMDA-NR1 in the PVN during CHF causing an increase in sympathetic nerve activity.

We have used neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid clone NG108-15 as our in vitro neuronal cell model that was derived by fusion of mouse neuroblastoma clone N18TG6 with rat glioma clone C6BU1. NG108 cells have neuronal properties and also have endogenous expression of nNOS8, and NMDAR 22, 32 components of the regulatory mechanisms that are also present in preautonomic neurons within the PVN. Thus, these cells were utilized to serve as a suitable surrogate for an in vitro “neuronal cell model” for our studies.

Over-expression of the glutamatergic NMDARs leads to increased sympathoexcitation and subsequent pathophysiological progression of disease states such as hypertension and heart failure. Hypoxic conditions in the brain can result from ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic lung disease, and congestive heart failure 33. HIF-1consists either of HIF-1α or HIF-2α, which is oxygen-regulated, and the constitutively expressed β-subunit termed HIF-1β, which are basic helix-loop-helix proteins of the PAS (Per, ARNT, Sim) family 34. Although it has long been assumed that blood flow to the brain remains relatively unchanged during heart failure 35, very small imperceptible changes in blood flow to areas of the brain highly vascularized (such as the PVN) could induce subtle but slight hypoxia in these areas. This relative hypoxia may lead to stabilization of HIF-1α and therefore, promote transcription of HIF-1 targeted genes. The molecular mechanism proposed in this study implies that the HIF-1 transcription complex may function as a central signal in the upregulation of the NMDA-NR1 in hypoxic conditions. Two HREs elements, designated as HRE1 and HRE2 were identified via a computer-based analysis of NMDA-NR1 promoter sequence (NCBI accession no. NM017010) 25. These elements containing the core sequence 5′-RCGTG-3′ were located between −473 and −356 bp upstream of the translation start site of the NMDA-NR1 gene and function as putative HIF-1 transcription factor-binding sites. Further studies are necessary to determine if the HIF-1 transcription complex is solely mediating this sympathoexcitation or is a contributory component of the overall sympathoexcitation that is commonly observed in CHF. Further, we did not see increased HIF-1α expression in adjacent regions such as Supraoptic nucleus (Supplemental Figure) but that does not preclude the possibility that HIF-1α could be increased in areas of the brain responsible for generation of sympathetic outflow utilizing the NMDA receptors, such as rostral ventrolateral medulla in the brainstem.

In the present studies, we observed significant increases in the HIF-1α transcript as well as protein levels, which lead us to speculate that in the PVN of these CHF rats, the HIF-1α transcription, as well as translation, may get affected. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is proline hydroxylated leading to a conformational change that promotes binding to the pVHL; E3 ligase complex followed by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation 1. In addition to oxygen -dependent degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, oxygen independent degradation was reported by the chaperone Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin 36 and p53-Mdm2 complex 37. Both hypoxic conditions and chemical hydroxylase inhibitors (such as desferrioxamine and cobalt) inhibit HIF-1α degradation and lead to its stabilization 38, 39. In contrast to protein stabilization, many investigators observed that HIF-1α mRNA levels increased following prolonged hypoxia40, 41 and also HIF-1α can be induced in an oxygen-independent manner by neurohumoral activators such as Angiotensin II (AngII) 42, 43, growth factors and cytokines44, 45. It is possible that the increased level of HIF-1α mRNA in the PVN of CHF rats that we have observed may be due to other factors such as AngII and cytokines that are also known to be elevated in CHF 46, 47.. AngII has been shown to induce expression of HIF-1α48 and NMDA-NR1 subunit22 in in vitro neuronal cells treated with AngII. Perhaps increased levels of AngII in CHF may be a contributory factor for the increased transcription of HIF-1 α and hence increased NMDAR mediated sympathoexcitation. The contribution of the AngII and cytokine systems within the PVN on HIF-1α levels in rats with CHF remains to be examined.

As discussed above, HIF-1α is not only regulated at posttranscriptional level but also at the transcriptional level via signaling pathways. A cross-talk between the NF-κB and HIF signaling pathways has also been reported. The different NF-κB subunits bind to the HIF-1α promoter 49 to activate HIF-1α transcription. TNF-α induced HIF-1α expression is dependent on NF-κB activation, and NF-κB silencing leads to reduced level of HIF-1α mRNA.49. AngII is known to activate NF-κB in the catecholaminergic CATH.a neurons and the upregulation of AT1 receptor gene transcription in response to AngII is initiated by CREB/NF-κB activation and propagated via downstream transcription factors Elk-1 and c-Fos 50. NF-κB and c-Fos have been proposed as key molecules in the pathophysiology of heart failure and hypertension 51 suggesting that perhaps these transcription factors are likely playing a critical role in HIF-1 α activation in the PVN during heart failure. In the ligand-induced activation of HIF-1, two major phosphorylation pathways are involved, the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways 52. In present studies, the increase in HIF-1α mRNA levels that we observed may be thru AngII-mediated activation of MAPK pathways. Additional experiments with AngII infused rat models would address these questions more specifically.

The sympathetic nervous system has been the focus of investigation and target for intervention in CHF 53. It has since been realized that sympathetic activity in CHF can be both beneficial and harmful. Moxonidine, which acts centrally through the imidazoline receptors to decrease sympathetic outflow, was associated with increased mortality, despite a significant reduction in plasma norepinephrine, at least in patients with severe CHF (MOXCON trial) 54. Thus, it has been suggested that modulation of sympathetic activity may remain an objective in this area but perhaps only in patients with moderate CHF in whom the enhanced sympathetic activity is probably deleterious. Our previous work has identified the PVN and specifically the imbalance between the excitatory glutamatergic and inhibitory NO mechanisms within this site to lead to detrimental sympathoexcitation in HF 6, 53, 55. Further, our recent studies have utilized the efficacy of ExT (4,5,6) 19, 56, 57 and RDN 58 to reduce sympathoexcitatory drive (interestingly appropriately without the adverse effects such as those observed in the MOXCON trial) to examine the changes in central mechanisms specifically within the PVN to identify a potential therapeutic target. Thus, recognizing the contribution of HIF-1α and NMDA receptors represent some new potential therapeutic targets for future clinical interventions to appropriately reduce sympathoexcitation without the detrimental effects. These results provide the insight into the possible underlying mechanisms that result in the beneficial effects of both ExT and RDN 19, 58.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that HIF-1α expression in the PVN of CHF rats was increased leading to exaggerated NMDAR mediated sympathoexcitation. Further, dissecting the molecular pathway involved in upregulation of HIF-1α in the PVN during CHF may help to identify novel therapeutic targets to alleviate the sympathoexcitation. Pharmacologic and gene therapy strategies designed to modulate HIF-1α activity may represent a novel and effective therapeutic approaches to alleviate the sympathoexcitation commonly seen in the CHF condition.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

A hallmark of chronic heart failure (CHF) is increased sympathetic drive leading to increased risk of morbidity and mortality. While there has been some progress in elucidating the peripheral mechanisms involved in these abnormalities, the role of central mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Our previous work has identified that the activation of paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus leads to detrimental sympathoexcitation in CHF via enhanced activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate-type1 receptors (NMDA-NR1) in the PVN. During CHF an imperceptibly subtle change of blood flow to highly vascularized brain area such as the PVN may induce slight hypoxia in this region. We studied whether hypoxia via hypoxia-inducible-factor 1α (HIF-1α) might contribute to the augmentation of the NMDA-NR1 mediated sympathoexcitatory responses from the PVN in CHF. Immunohistochemistry staining, mRNA, and protein for HIF-1α were up regulated within the PVN of rats with CHF. Silencing of HIF-1α in neuronal cells (NG108) lead to a significant decrease in expression of NMDA-NR1 suggesting that expression of HIF-1α is necessary for the upregulation of NMDA-NR1. Further, HIF-1α silencing within the PVN abrogated the increased basal sympathetic tone as well as sympathoexcitatory responses to microinjection of NMDA in the PVN of rats with CHF. Our results show a critical role for HIF-1α in the up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 to mediate sympathoexcitation in CHF. We conclude that subtle hypoxia within highly vascular brain areas such as the PVN may act as a critical cue to modulate sympathoexcitation during CHF with potential therapeutic target implications

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Dr. Lirong Xu is greatly appreciated.

Sources of Funding

Funding from American Heart Association-14SDG19980007 and NIH, Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, R56 HL124104, and PO1 HL62222 grant supported the work.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Safran M, Kaelin WG., Jr Hif hydroxylation and the mammalian oxygen-sensing pathway. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:779–783. doi: 10.1172/JCI18181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger RH. Mammalian oxygen sensing, signalling and gene regulation. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:1253–1263. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badoer E. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and cardiovascular regulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:95–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawabe T, Chitravanshi VC, Kawabe K, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular function of a glutamatergic projection from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;153:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen XQ, Du JZ, Wang YS. Regulation of hypoxia-induced release of corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat hypothalamus by norepinephrine. Regul Pept. 2004;119:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li YF, Cornish KG, Patel KP. Alteration of nmda nr1 receptors within the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus in rats with heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;93:990–997. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000102865.60437.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang K, Li YF, Patel KP. Blunted nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of renal nerve discharge within pvn of rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H995–H1004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma NM, Zheng H, Mehta PP, Li YF, Patel KP. Decreased nnos in the pvn leads to increased sympathoexcitation in chronic heart failure: Role for capon and ang ii. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:342–357. doi: 10.1093/cvr217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen AM. Inhibition of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in spontaneously hypertensive rats dramatically reduces sympathetic vasomotor tone. Hypertension. 2002;39:275–280. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai G, Hoffman PW. Transcriptional regulation of nmda receptor expression. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buller AL, Larson HC, Schneider BE, Beaton JA, Morrisett RA, Monaghan DT. The molecular basis of nmda receptor subtypes: Native receptor diversity is predicted by subunit composition. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5471–5484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05471.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori H, Mishina M. Structure and function of the nmda receptor channel. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1219–1237. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four nmda receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishi M, Hinds H, Lu HP, Kawata M, Hayashi Y. Motoneuron-specific expression of nr3b, a novel nmda-type glutamate receptor subunit that works in a dominant-negative manner. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salter MW, Dong Y, Kalia LV, Liu XJ, Pitcher G. Regulation of nmda receptors by kinases and phosphatases. In: Van Dongen AM, editor. Biology of the nmda receptor. Boca Raton (FL): 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel KP, Zhang PL, Krukoff TL. Alterations in brain hexokinase activity associated with heart failure in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1993;265:R923–R928. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K, Li YF, Patel KP. Reduced endogenous gaba-mediated inhibition in the pvn on renal nerve discharge in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:R1006–R1015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00241.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li YF, Wang W, Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Angiotensin-mediated increase in renal sympathetic nerve discharge within the pvn: Role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1035–1043. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00338.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng H, Li YF, Cornish KG, Zucker IH, Patel KP. Exercise training improves endogenous nitric oxide mechanisms within the paraventricular nucleus in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2332–2341. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00473.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palkovits M, Brownstein M. Brain microdissection techniques. In: Cuello AE, editor. Brain microdissection techniques. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright WE, Shay JW. Inexpensive low-oxygen incubators. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2088–2090. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiber AC, Zheng H, Sharma NM, Patel KP. Chronic at1 receptor blockade normalizes nmda-mediated changes in renal sympathetic nerve activity and nr1 expression within the pvn in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;1152:1546–1555. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01006.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Hu Q, Yan J, Yang X, Shi X, Lei J, Chen L, Huang H, Han J, Zhang JH, Zhou C. Early inhibition of hif-1alpha with small interfering rna reduces ischemic-reperfused brain injury in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen DHZT, Shu J, Mao JH. Quantifying chromogen intensity in immunohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. Cancer InCytes, Protocol Exchange. 2013;2:e1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh SH, Hung JJ, Gean PW, Chang WC. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protects cultured cortical neurons from lipopolysaccharide-induced cell death via regulation of nr1 expression. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14259–14270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4258-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman MC, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates angiotensin ii-induced influx of extracellular calcium in neural cells. Hypertension. 2005;45:717–723. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153463.22621.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang RF, Yin JX, Li YL, Zimmerman MC, Schultz HD. Angiotensin-(1–7) increases neuronal potassium current via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C58–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malpas SC, Head GA, Anderson WP. Renal responses to increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity induced by brainstem stimulation in rabbits. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1996;61:70–78. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(96)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malpas SC. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:513–557. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moroz E, Carlin S, Dyomina K, Burke S, Thaler HT, Blasberg R, Serganova I. Real-time imaging of hif-1alpha stabilization and degradation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rungta RL, Choi HB, Lin PJ, Ko RW, Ashby D, Nair J, Manoharan M, Cullis PR, Macvicar BA. Lipid nanoparticle delivery of sirna to silence neuronal gene expression in the brain. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e136. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohkuma S, Katsura M, Chen DZ, Chen SH, Kuriyama K. Presence of n-methyl-d-aspartate (nmda) receptors in neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid ng108-15 cells-analysis using [45ca2+]influx and [3h]mk-801 binding as functional measures. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;22:166–172. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenza GL, Agani F, Feldser D, Iyer N, Kotch L, Laughner E, Yu A. Hypoxia, hif-1, and the pathophysiology of common human diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;475:123–130. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46825-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-pas heterodimer regulated by cellular o2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selwyn AP, Shea MJ, Foale R, Deanfield JE, Wilson R, de Landsheere CM, Turton DL, Brady F, Pike VW, Brookes DI. Regional myocardial and organ blood flow after myocardial infarction: Application of the microsphere principle in man. Circulation. 1986;73:433–443. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mimnaugh EG, Martinez A, Cuttitta F, Neckers LM. Hsp90 regulates a von hippel lindau-independent hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha-degradative pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29936–29944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, Dillehay LE, Madan A, Semenza GL, Bedi A. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:34–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Desferrioxamine induces erythropoietin gene expression and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 DNA-binding activity: Implications for models of hypoxia signal transduction. Blood. 1993;82:3610–3615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan Y, Hilliard G, Ferguson T, Millhorn DE. Cobalt inhibits the interaction between hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha and von hippel-lindau protein by direct binding to hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15911–15916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belaiba RS, Bonello S, Zahringer C, Schmidt S, Hess J, Kietzmann T, Gorlach A. Hypoxia up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transcription by involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nuclear factor kappab in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4691–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uchida T, Rossignol F, Matthay MA, Mounier R, Couette S, Clottes E, Clerici C. Prolonged hypoxia differentially regulates hypoxia-inducible factor (hif)-1alpha and hif-2alpha expression in lung epithelial cells: Implication of natural antisense hif-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14871–14878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorlach A, Diebold I, Schini-Kerth VB, Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Roth U, Brandes RP, Kietzmann T, Busse R. Thrombin activates the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 signaling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells: Role of the p22(phox)-containing nadph oxidase. Circ Res. 2001;89:47–54. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richard DE, Berra E, Pouyssegur J. Nonhypoxic pathway mediates the induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26765–26771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haddad JJ, Land SC. A non-hypoxic, ros-sensitive pathway mediates tnf-alpha-dependent regulation of hif-1alpha. FEBS Lett. 2001;505:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stiehl DP, Jelkmann W, Wenger RH, Hellwig-Burgel T. Normoxic induction of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha by insulin and interleukin-1beta involves the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zucker IH, Wang W, Pliquett RU, Liu JL, Patel KP. The regulation of sympathetic outflow in heart failure. The roles of angiotensin ii, nitric oxide, and exercise training. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:431–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guggilam A, haque M, Kerut EK, McIlwain E, Lucchesi P, Seghal I, Francis J. Tnf-alpha blockade decreases oxidative stress in the paraventricular nucleus and attenuates sympathoexcitation in heart failure rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H599–609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00286.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf G, Schroeder R, Stahl RA. Angiotensin ii induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in pc 12 cells through a posttranscriptional mechanism: Role of at2 receptors. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:415–421. doi: 10.1159/000080086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Uden P, Kenneth NS, Rocha S. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by nf-kappab. Biochem J. 2008;412:477–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haack KK, Mitra AK, Zucker IH. Nf-kappab and creb are required for angiotensin ii type 1 receptor upregulation in neurons. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karin M, Takahashi T, Kapahi P, Delhase M, Chen Y, Makris C, Rothwarf D, Baud V, Natoli G, Guido F, Li N. Oxidative stress and gene expression: The ap-1 and nf-kappab connections. Biofactors. 2001;15:87–89. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520150207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westra J, Brouwer E, Bos R, Posthumus MD, Doornbos-van der Meer B, Kallenberg CG, Limburg PC. Regulation of cytokine-induced hif-1alpha expression in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1108:340–348. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel KP. Role of paraventricular nucleus in mediating sympathetic outflow in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2000;5:73–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1009850224802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohn JN, Pfeffer MA, Rouleau J, Sharpe N, Swedberg K, Straub M, Wiltse C, Wright TJ Investigators M. Adverse mortality effect of central sympathetic inhibition with sustained-release moxonidine in patients with heart failure (moxcon) Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:659–667. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y-F, Patel KP. Paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and elevated sympathetic activity in heart failure: Altered inhibtory mechanisms. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:17–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patel KP, Zheng H. Central neural control of sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure following exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H527–537. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00676.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng H, Sharma NM, Liu X, Patel KP. Exercise training normalizes enhanced sympathetic activation from the paraventricular nucleus in chronic heart failure: Role of angiotensin ii. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R387–394. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00046.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel KP, Xu B, Liu X, Sharma NM, Zheng H. Renal denervation improves exaggerated sympathoexcitation in rats with heart failure: A role for neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the paraventricular nucleus. Hypertension. 2016;68:175–184. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.