Abstract

Genetic etiologies for congenital anomalies of the facial skeleton, namely, the maxilla and mandible, are important to understand and recognize. Malocclusions occur when there exist any significant deviation from what is considered a normal relationship between the upper jaw (maxilla) and the lower jaw (mandible). They may be the result of anomalies of the teeth alone, the bones alone, or both. A number of genes play a role in the facial skeletal development and are regulated by a host of additional regulatory molecules. As such, numerous craniofacial syndromes specifically affect the development of the jaws. The following review discusses several genetic anomalies that specifically affect the bones of the craniofacial skeleton and lead to malocclusion.

Keywords: malocclusion, mandible, maxilla, congenital, Treacher Collins, mandibulofacial dysostosis, Nager, Miller

Introduction

The development of the face is a dynamic process that starts with a relatively rapid and orderly composition of both mesodermal and cranial neural crest cells via a complex signaling network. During normal embryogenesis, the first and second branchial arches form facial prominences that develop into specific craniofacial and skeletal structures. Portions of the first branchial (or mandibular) arch develop into the skeletal, muscular, and neural elements of the mandible, whereas the dorsal edge of the first branchial (or hyomandibular) cleft forms the auditory meatus.

The size and growth of each of the facial bones are in part genetically predetermined, yet environmental influences play a role. Malformations occur when there is perturbation due to genetic anomalies, environmental influences, or both.1 Malocclusion is defined as any significant deviation from what is considered a normal relationship between the upper jaw (maxilla) and lower jaw (mandible). Angle classified a patient's occlusion by the relationship of the maxillary and mandibular first molar teeth.2 A class I occlusion is considered normal and occurs when the mesiobuccal cusp of the first maxillary molar articulates with the buccal groove of the first mandibular molar. This is noted in roughly 30 to 40% of the population.

Malocclusions may be the result of dental anomalies, skeletal anomalies, or both. Many different variables comprise the normal occlusion, including the size of the maxilla; the size of the mandible; the number, size, and position of the upper teeth; the number, size, and position of the lower teeth; the surrounding perioral soft tissue anatomy; as well as environmental factors. Severe malocclusions or dentofacial anomalies are noted in roughly 20% of the population. When there is some combination of maxillary and/or mandibular hyperplasia or hypoplasia, a skeletal malocclusion will result.

All bones develop within a functional milieu that is composed of environmental conditions, including muscle strength, bone length, and craniofacial dimensions among others. Some of these may be genetic. Soft tissue influences, such as lip incompetence and tongue protrusion on upper incisor proclination and lower lip closure on lower incisor retroclination, may thus have significant influences on the occlusion. Salzmann demonstrated the concordance between familial tongue thrusting and jaw posturing and resulting occlusions or malocclusions.3 There may also exist profoundly negative influences, such as illness, starvation, and stress.4

Homeobox genes function in regulating the pattern of the developing embryo and as such are highly conserved across diverse organisms. They encode transcription factor proteins that regulate the creation of RNA from a DNA template. The homeobox genes are likely to play a role in the development of specialized organ systems. The Msx1 and Msx2 (muscle segment) genes, the Hox genes, and the Shh (sonic hedgehog) gene, among others, likely play important roles. Their function is expressed through several regulatory molecules, including fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor-α, transforming growth factor-β, and many bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs).5 These molecules coordinate cell interactions and cell migrations that regulate growth. Different regions of DNA are activated in different cells to regulate which proteins are produced in which organ systems. Polymorphisms in these genes are prime targets in the search for maxillary and mandibular developmental anomalies.

Class II Malocclusion

An Angle class II malocclusion is more commonly referred to as an “overbite,” and more technically defined when the mesiobuccal cusp of the first maxillary molar lies anterior to the corresponding mandibular buccal groove. The class II, division 1 malocclusion occurs when there is a deep overbite, excessive overjet, and normal or proclined incisors. This occurs more commonly when the mandible is underdeveloped rather than a hyperplastic maxilla. Specifically, the body of the mandible is smaller and the overall length is reduced.6

The class II, division 2 malocclusion occurs when there is a deep overbite and retroclined incisors. These patients demonstrate a high lip line and hyperactivity of the mentalis muscle, which strains to get the lips to meet. Regarding a genetic influence, prior studies have highlighted this morphology in family pedigrees7 and twin and triplet studies.8 The latter examined the phenotype and cephalograms of 48 pairs of twins and 6 sets of triplets. There was 100% concordance of the malocclusion among the monozygotic twins and 10% among the dizygotic twins.

Class III Malocclusion

A class III malocclusion is commonly referred to as an “underbite” and technically defined when the mesiobuccal cusp of the first maxillary molar is in a posterior position (Fig. 1). The class III skeletal deformity is a dentofacial phenotype that can be the result of a mandible that is disproportionately larger than other facial structures, or a maxilla that is disproportionately smaller than other facial structures or a combination of the two (Fig. 2). Several anatomic discrepancies can result from this type of growth pattern, and is expressed in varying degrees depending on the subtype. Nevertheless, the discrepancies can be present in all three dimensions of growth. Vertically, the facial structures (maxilla/mandible or both) can be excessive or deficient. Transversely, the clinical presentation can be a maxillary constriction, mandibular overgrowth, or a combination of both. In the sagittal plane, the presentation is most often noted by the relative mandibular prognathism.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative class III malocclusion.

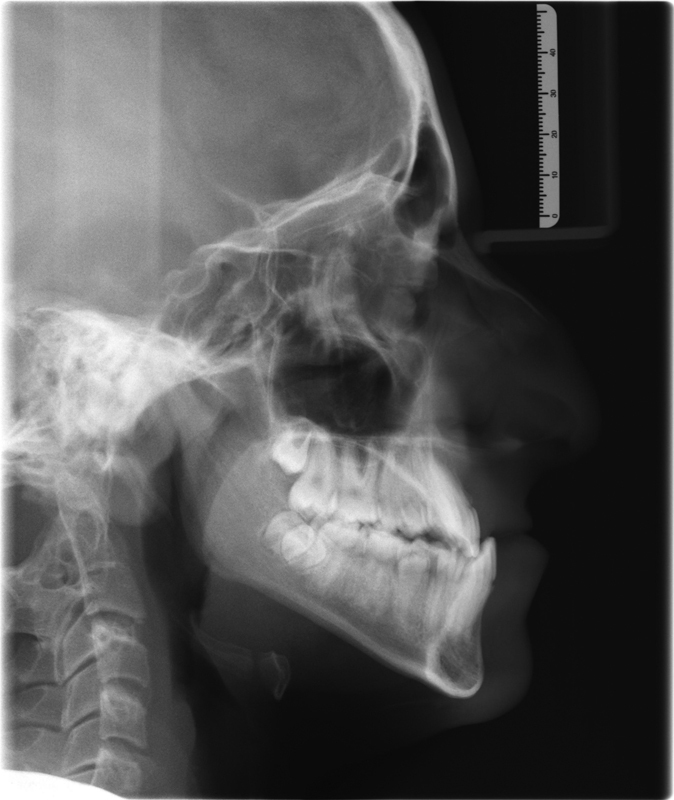

Fig. 2.

Cephalometric radiograph of Class III skeletal growth pattern.

Due to a lack of coordination between the dental arches, the teeth often compensate by changing their angulation to mask the severity of the malocclusion. Pressure from the lips and tongue compensate for the bony abnormality by retroclining the lower incisors and proclining the upper incisors. If the jaw base is deficient, then dental crowding and ectopic eruption are often present. Conversely, if the jaw base is excessive, then dental spacing is usually noted. The resulting soft tissue changes include a deep labiomental fold, a prominent nasolabial fold, and a lack of infraorbital and alar support.

The prevalence of a class III malocclusion varies from 1 to 5% in the Caucasian population in the United States to 20 to 25% in Asian populations. A class III skeletal growth pattern may be noted with the primary dentition (often referred to as congenital malocclusion) or with the mixed or permanent dentition (developmental malocclusion). The resulting functional and psychological handicap can range in severity, and it is estimated that half of these individuals require orthognathic surgery as the only treatment modality.9 Based on radiographic data, the anomaly may not be isolated to the jaws. Finite element analysis demonstrated an acute cranial base angle and shortened posterior cranial base that contributed to a more anterior position of the glenoid fossa and thus a more prognathic mandible.10

Class III skeletal deformities have been attributed to both genetic and environmental etiologies. There has been much debate as to which is the greater influence. Angle argued that malocclusion arises as a result of local factors that influence the shape and position of the jaws relative to one another. This may include enlargement of the tonsils,2 blockage of the nasal passages,11 endocrine abnormalities,12 posture, and trauma.13 The preponderance of evidence for the genetic influence in malocclusion comes from family and twin studies. Boys have been shown to have a greater similarity to their parents than girls, especially when comparing the transmission from mothers to sons versus mothers to daughters.14 Linear cephalometric measurements have been compared in fraternal and identical twin pairs and have demonstrated significant variability between the two groups regarding anterior cranial base dimensions, mandibular body length, and total facial height.15 Other twin studies, however, argue against this by showing either disparity among families or even members of monozygotic twin pairs.16

This anomaly was historically noted in the Hapsburg family line of Hungary and Austria. A study of the family pedigree revealed this to be an autosomal-transmitted trait.17 This was similarly noted in the families of Japanese patients with a class III malocclusion where there was a higher incidence of a class III malocclusion than in the families of patients with a normal occlusion.18 Concordance of malocclusion was six times higher in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins.19 Based on lateral cephalometry data, Watnick further hypothesized that certain areas of the mandible were under greater genetic control, including the lateral ramus and lingual symphysis.20 Other areas by reasoning, such as the antegonial notch, were therefore under predominantly environmental control.

In cases involving a familial recurrence of mandibular prognathism, many studies have investigated the molecular basis for the observed disorders. While specific genes have not yet been reported, multiple mandibular prognathism susceptibility loci have been identified with mouse phenotypes consistent with a role in mandibular development (Table 1). Although this is an important first step in understanding mandibular prognathism, it does not cover the full spectrum of class III skeletal malocclusion, as it addresses only two of the five subtypes listed in Table 2. Thus, these studies are currently of limited value to the clinician.

Table 1. Genes associated with mandibular prognathism and implicated in craniofacial or skeletal development in mice.

| Gene | Evidence | Mouse mutants |

|---|---|---|

| Plxna2 | GWAS21 | No reported craniofacial or skeletal phenotype |

| Ssx2ip | GWAS13 | Unknown |

| Ghr | SNP9 22 | Reduced postnatal growth, impaired bone development23 |

| Col2a1 | SNP24 25 | Failed cartilage development, shortened limbs, cleft palate26 |

| Kat6b | Microarray/rt-qPCR27 | Abnormal brain/cranium development, abnormal jaw morphology28 |

| Hdac4 | Microarrayrt-qPCR17 | Abnormal skeletal morphology, domed cranium, premature endochondral ossification, exencephaly29 |

| Dusp6 | Whole exome seq30 | Abnormal cranium, middle ear morphology31 |

| Tgfb3 | Genome wide linkage scan32 | Cleft palate, abnormal cartilage33 |

| Ltbp2 | Genome wide linkage scan19 | No reported craniofacial or skeletal phenotype |

| Matn1 | SNP-PCR34 | Overtly normal35 |

| Igf1 | Genome wide linkage scan17 | Variable phenotype, skeletal defects, delayed ossification36 |

| Hoxc | Genome wide linkage scan17 | Vertebral transformations37 |

Table 2. Five subtypes comprising class III skeletal malocclusions.

| 1. Mandibular prognathism, long face |

| 2. Maxillary deficient, low angle |

| 3. Maxillary deficient, high angle |

| 4. Mild mandibular prognathism, normal |

| 5. Combination, normal |

Suture development in the cranium has been related to FGF genes. The dura mater overlying the brain, through an FGF pathway, is thought to signal the overlying suture and prevent premature ossification.38 Mutations in the FGF receptor protein have been noted in several craniofacial syndromes where premature suture fusion is a hallmark. These include Apert, Crouzon, and Pfeiffer syndromes, which also present with class III malocclusion.39

When the above pathways are disturbed, anomalies are seen. Hemifacial microsomia is believed to be a disordered migration of neural crest cells. In patients with cleidocranial dysostosis, an autosomal dominant mutation in the core binding factor 1 gene (CBFA1) causes improper signaling between periosteum and chondrocytes and results in anomalies of the membranous bones of the cranium and clavicles.40 Similarly, in Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) there is a defect in a gene located on chromosome 5 responsible for the production of the treacle protein leading to hypoplasia of the zygomatic arch and mandible, as well as cleft palate and deafness.41

Syndromic Malocclusions

Manifestations of first and second branchial arches anomalies depend on which phase of neural crest cell development is disrupted (formation vs. differentiation). For example, if neural crest cell formation is perturbed, such as few neural crest cells are produced or they fail to migrate to final destinations, this can result in phenotypes of small noses, jaws, and ears as well as cleft palate. The characteristic disorder of this abnormal type is TCS.42 Aberrant neural crest cell differentiation, on the other hand, results in premature suture mesenchyme ossification, which fuses the calvarial bones (craniosynostosis) consequently restricting skull growth and impacting upon facial and brain growth, development, and maturation.43

Mandibulofacial dysostosis (MFD), a heterogeneous group of developmental disorder of the first and second branchial arches, is characterized by malar and mandibular hypoplasia, slanting of the palpebral fissures, exophthalmos with ectropion, coloboma of the lower lid, macrostomia, dysplastic ears which can be associated with conductive hearing loss, and cleft palate. Associated anomalies may include choanal atresia, and/or lacrimal atresia.44 45 Computed tomography imaging of the skull may demonstrate zygomatic arch clefts in some individuals. A major subgroup of the MFD comprises those with frequent limb defects, known as acrofacial dysostoses (AFDs).46 The best-known syndromic MFD is TCS, which is caused by mutations in TCOF1, POLR1D, or POLR1C. Nager and Miller syndromes, both much rarer, are AFDs caused by mutations in SF3B4 and DHODH, respectively. More recently, mutations in EFTUD2 (elongation factor TU GTP-binding domain containing 2) have been shown to cause MFD, Guion-Almeida type (MFDGA), also known as MFD with microcephaly or AFD type Guion-Almeida.47 48 49 50 Other MFD syndromes are less well characterized and their specific genetic etiologies are still unknown. These MFDs include autosomal dominant types, such as Hedera–Toriello–Petty,51 Bauru,52 as well as the X-linked type Toriello.53

Treacher Collins Syndrome

TCS, also known as Franceschetti–Klein syndrome, is the most common MFD affecting ∼1/50,000 live births.54 It was first described by a British ophthalmologist Edward Treacher Collins in 1900 and subsequently classified as MFD by the Swiss ophthalmologist Adolphe Franceschetti and Klein in 1949.55

TCS is caused by impaired development of the first and second branchial arches during the early embryonic stage and primarily affects the mid and lower face. The signs and symptoms of this disorder vary greatly, ranging from cases of obstruction sleep apnea due to airway narrowing by severe micrognathia to those that remain clinically undiagnosed. Characteristic clinical features of TCS are symmetrical in nature and include: (1) external ears abnormalities, external auditory canals atresia, middle ear ossicles malformation which result in bilateral conductive hearing loss (mixed or sensorineural hearing loss is rare); (2) lateral downward slanting of palpebral fissures, coloboma of the lower eyelid with lack of eyelashes medial to the defect; (3) hypoplasia of facial bones, particularly the maxilla, mandible, and zygomatic complex which result in macrostomia and micrognathia; (4) high arched palate, more than half cases with cleft palate with or without cleft lip.41 Other rarer features include microcephaly, mental retardation, and psychomotor delay.56 57 Some patients have additional ophthalmological findings, such as vision loss, strabismus, amblyopia, refractive error, anisometropia, and delayed-onset infantile cataracts. Hypoplasia of the facial bones often results in dental anomalies, including class II malocclusion, anterior open bite, and temporomandibular joint dysplasia. Craniosynostosis is not a feature of TCS but most patients have an abnormal cranium shape.

About 40% of TCS patients have positive family history and the remaining 60% cases possibly arise as a result of de novo mutations. So far, more than 250 heterozygous disease-causing TCOF1 mutations have been identified in a majority of patients (71–93%), spanning the whole gene region. Of these variants, 57% are small deletions or insertions, 16% are splice-site mutations, 23% nonsense mutations, and 4% missense mutations.58 Large deletions of one or more exon have also been found in up to 5% of TCS patients.58 59 In one case, a synonymous mutation in TCOF1 led to missplicing of a constitutive exon.60 Although several mutations have occurred more than once, only one mutation, c.4369_4373delAAGAA, has been identified as commonly recurrent. This mutation is present in 16% of individuals with an identifiable mutation. Because the majority of mutations lead to the introduction of a premature termination codon, it is likely that RNA transcripts from the abnormal gene are lost as a result of haploinsufficiency and nonsense-mediated decay of functional TCOF1 protein.61

Missense mutations that allow production of an abnormal protein can disrupt either the N- or C-terminus nuclear localization signals and affect the TCOF1 ability to transport into the nucleus, causing neural crest cells to undergo apoptosis during embryogenesis.61 62 In addition to the TCOF1 gene, two additional genes accounting for an approximate 9% of TCOF1-negative patients. These two RNA polymerase 1 polypeptide genes: POLR1C (OMIM 613715) and POLR1D (OMIM 613715), located on 13q12.2 and 6p22.3, encoding subunits of the RNA polymerases I and III respectively.63 Similar to TCOF1, mutations in POLR1D are also dominant and lead to haploinsufficiency of RNA polymerase 1 polypeptide D. However, mutations in POLR1C act in an autosomal recessive way. Compound heterozygous mutations in this gene lead to functional depletion. Since then, it is known that TCS is mostly inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, but autosomal recessive inheritance is also possible. Some individuals with typical clinical signs of TCS do not have mutations in TCOF1, POLR1C, or POLR1D, therefore, other genes need to be identified in the future.

TCOF1 (OMIM 606847), located on 5q32–q33.1, comprises 26 coding exons and encodes a serine/alanine-rich, nucleolar phosphoprotein: treacle. Treacle is a 144-kDa serine/alanine-rich nucleolar phosphoprotein with a function that has yet to be fully established. Bioinformatics analyses indicated that treacle contains three domains; unique amino and carboxy termini, and a characteristic central repeat domain. Evidence has shown that treacle is involved in ribosomal DNA gene transcription through its interaction with an upstream binding factor,63 and perhaps neural crest cell migration.64 Treacle haploinsufficiency in patients with TCS may result in abnormal development caused by inadequate ribosomal RNA production in the prefusion neural folds during the early stages of embryogenesis.65 POLR1D and POLR1C are RNA polymerase 1 binding factor, implicating that TCS is a ribosomopathy and these three genes involved in ribosome biogenesis are essential for cell growth and proliferation. It will be interesting to explore the function of POLR1C and POLR1D and determine whether they share similar or overlapping functions with TCOF1 during embryogenesis and in the pathogenesis of TCS.

Mouse studies revealed that TCOF1 is broadly expressed in both embryonic and adult tissues. The extent and severity of the phenotype in TCOF1+/− mouse were dependent on the mouse genetic background. TCOF1+/− neonates obtained through an intercross of DBA heterozygotes and wildtype C57BL/6 mice exhibited phenotypes that mimicked human TCS, including frontonasal hypoplasia, particularly of the maxilla and mandible, together with high arched or cleft palate, and choanal atresia or agenesis of the nasal passages. The zygomatic arch, tympanic ring, and middle ear ossicles are all hypoplastic and misshapen.42 TCOF1+/− neonates displayed gasping behavior and abdominal distention and died within 24 hours of birth. Skeletal analysis indicated that TCOF1+/− neonates died from respiratory arrest due to malformations of the nasal, premaxilla, maxilla, and palatine skeletal elements. Whole embryo culture of wild-type and TCOF1+/− mouse embryos showed that TCOF1 haploinsufficiency resulted in neural crest cell precursors through neuroepithelial apoptosis, which results in a reduced number of neural crest cells migrating into the developing craniofacial complex. Thus, TCOF1+/− haploinsufficient mice provided an important resource to decipher the in vivo cellular basis of TCS together with the biochemical function of treacle. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of p53 in TCOF1+/− embryos can suppress neuroepithelial apoptosis ensuring the normal production of migrating neural crest cells. Remarkably, this can prevent the pathogenesis of craniofacial anomalies characteristic of TCS in TCOF1+/− mouse.66 Interestingly, the rescue phenomenon occurred without restoration of ribosome biogenesis, which implies that TCOF1 may play other essential roles in neural progenitor cell and neural crest cell survival distinct from its previously recognized function in ribosome biogenesis. Treacle has been shown in vivo to localize to the centrosome during metaphase and play a key role in regulating chromosome segregation.67 Perturbation of one or more of these functions may underpin the activation of p53 and provide additional ways to prevent TCS.

Mandibulofacial Dysostosis

MFDGA or MFD with microcephaly (MFDM) is a rare sporadic syndrome comprising craniofacial malformations and microcephaly. MFDGA was first described by Guion-Almeida et al,68 who reported four sporadic patients presenting with MFD, microcephaly, developmental delay, cleft palate, characteristic dysplastic external ears with preauricular tags and radial ray anomalies. They proposed that this condition is a new syndrome distinct from the known MFDs. The same group subsequently reported a mother and a son with MFD, intellectual disability, microcephaly, and growth retardation.69 MFDM is characterized by malar and mandibular hypoplasia; microcephaly (congenital or postnatal onset); malformations of the pinna, auditory canal, and/or middle ear (ossicles and semicircular canals) with associated conductive hearing loss; distinctive facial features (metopic ridge, up- or downslanting palpebral fissures, prominent glabella, broad nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, and everted lower lip). Associated craniofacial malformations may include cleft palate, choanal atresia, and facial asymmetry. Intellectual disability (ID) is a prominent feature. Major extracranial malformations include: esophageal atresia (40%), congenital heart disease (40%), and thumb abnormalities (25%). Short stature is present in approximately one-third of individuals. Because half of the patients with this condition known as MFD type Guion-Almeida have thumb anomalies, they should be reclassified as AFD type Guion-Almeida. The microcephaly in AFD type Guion-Almeida, which is usually absent in Nager syndrome, might help to distinguish these conditions.

Recently, several whole exome sequencing studies have revealed causative mutations in EFTUD2 (elongation factor TU GTP-binding domain-containing 2, OMIM 603892).70 71 72 Collectively, a range of mutation types have been uncovered, including large deletions and frameshifts, splice-site, nonsense, and missense mutations were identified, consistent with haploinsufficiency as the disease mechanism (Table 3). Therefore, MFDM is the first multiple malformation syndrome attributed to a defect of the major spliceosome, which is critical for removing introns and ligating exon splicing during transcription. EFTUD2 encodes U5–116-kDa protein, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein, occupies a central position within the U4/U6-U5 tri-snRNP particle. It is a highly conserved spliceosomal GTPase that plays an important role in either the splicing process itself or the recycling of spliceosomal snRNPs.73 The defects observed in individuals with MFDM could be due to aberrant splicing of genes involved in craniofacial development. However, to date, nothing is known about the spatiotemporal activity of EFTUD2 during embryogenesis. Eftud2 is widely expressed in E11.5 mice, with more intense expression in the distal limb bud, the lung bud, trachea, esophagus, mandibular mesenchyme, the ventricular zone of the forebrain, and the epithelium of the otic vesicle.74 These observations are consistent with the pattern of affected derivatives in MFDM patients. Interestingly, EFTUD2 mutations lead to a complex multiple malformation syndrome with ID, whereas mutations in other genes encoding spliceosomal subunits (hBrr2, hPRP8, hPRP6, and hPRP31) only produce retinitis pigmentosa, a result of the tissue-specific death of photoreceptor cells. In addition, mutations in EFTUD2 are also causative of a type of syndromic esophageal atresia (EA), namely, AFD with EA. Thus, phenotypes caused by EFTUD2 mutations are important in the differential diagnoses of CHARGE and Feingold syndromes. Eftud2 loss-of-function mutant animals will help to elucidate the underlying pathogenesis in vivo.

Table 3. List of EFTUD2 mutations identified in patients with MFDGA syndrome (updated to 2014).

| Nucleotide change | Protein | Location | Predicted effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| c.198C > G | p.Y66* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.351–1G > C | N/A | Intron 4 | Splicing |

| c.498C > A | p.C166* | Exon 7 | Nonsense |

| c.529–1G > A | N/A | Intron 7 | Splicing |

| c.594T > G | p.Y198* | Exon 8 | Nonsense |

| c.619 + 1G > A | N/A | Intron 8 | Splicing |

| c.620–1G > T | N/A | Intron 8 | Splicing |

| c.623A > G | p.H208R | Exon 9 | Missense |

| c.670G > A | p.G224R | Exon 9 | Missense |

| c.698delA | N/A | Exon 9 | Frameshift |

| c.702 + 1del | N/A | Intron 9 | Splicing |

| c.702 + 5G > C | N/A | Intron 9 | Splicing |

| c.745G > T | p.E249* | Exon 10 | Nonsense |

| c.784C > T | p.R262W | Exon 10 | Missense |

| c.784_785delCGins TGATCCTGGAGC |

p.Arg262fs*1 | Exon 10 | Frameshift |

| c.994 + 1G > C | N/A | Intron 12 | Splicing |

| c.1058 + 3_1058 + 7delAAGTA | N/A | Intron 12 | Possibly splicing |

| c.1172_1179delGCCTCCCA | p.Ser391fs*57 | Exon 12 | Frameshift |

| c.1757_1758delCT | N/A | Exon 13 | Frameshift |

| c.1759_1760delGT | N/A | Exon 13 | Frameshift |

| c.1149 + 5G > T | N/A | Intron 13 | Splicing |

| c.1221G > C | p.E407D | Exon 15 | Missense |

| c.1306C > G | p.Q436E | Exon 15 | Missense |

| c.1426T > C | p.C476R | Exon 16 | Missense |

| c.1435dupA | p.Thr479Asnfs*2 | Exon 16 | Frameshift |

| c.1607 + 3A > G | p.Tyr537fs*25 | Intron | Splicing |

| c.1705C > T | p.R569* | Exon 17 | Nonsense |

| c.1758_1759del | p.Ser586fs*19 | Exon 17 | Frameshift |

| c.1860G > C | p.K620N | Exon 18 | Missense |

| c.1910T > G | p.L637R | Exon 19 | Missense |

| c.1962 + 1G > A | N/A | Intron 19 | Splicing |

| c.1976delTinsCCACC | p.Val659Alafs*7 | Exon 20 | Frameshift |

| c.2155C > T | p.Q719* | Exon 22 | Nonsense |

| c.2198G > A | p.W733* | Exon 22 | Nonsense |

| c.2245dupA | p.Thr749Asnfs*5 | Exon 22 | Frameshift |

| c.2259 + 1G > A | N/A | Intron 22 | Splicing |

| c.2296delA | p.Ile766Serfs*18 | Exon 23 | Frameshift |

| c.2467–1G > T | N/A | Intron 24 | Splicing |

| c.2485G > A | p.E829K | Exon 24 | Missense |

| c.2493C > A | p.Y831* | Exon 24 | Nonsense |

| c.2496C > G | p.Y832* | Exon 24 | Nonsense |

| c.2562–1G > A | N/A | Intron 25 | Splicing |

| c.2562–2delA | N/A | Intron 25 | Splicing |

| c.2562–2_2562–1delAG | N/A | Intron 25 | Splicing |

| c.2566C> | T p.H856Y | Exon 26 | Missense |

| c.2619_2621delTTTinsGGTC | p.Phe874Valfs*11 | Exon 26 | Frameshift |

| c.2622dupT | N/A | Exon 26 | Frameshift |

| c.2770C > T | p.Q924* | Exon 26 | Nonsense |

| c.2823 + 1delG | N/A | Intron 27 | Splicing |

Abbreviation: N/A, not available.

Nager Syndrome

Nager syndrome is the best-known subgroup of preaxial acrofacial dysostoses (AFD). First described in 1948 by Nager and De Reynier,75 the anomaly is due to aberrations in development of the first and second branchial arches and limb buds. The main clinical features are: (1) craniofacial abnormalities, such as downslanting palpebral fissures, malar hypoplasia, micrognathia, atresia of the external auditory canal as well as bilateral conductive hearing loss, and cleft palate; (2) preaxial limb defects, such as radial and thumb hypoplasia or aplasia, duplication of thumbs or proximal radioulnar synostosis. Involvement of the lower extremities has been described,76 77 but is usually considered an uncommon feature of Nager syndrome. Other associations observed in clinically diagnosed patients with Nager syndrome include genitourinary abnormalities, such as vesicoureteral reflux, duplication of the ureter or renal agenesis, cardiovascular abnormalities, such as ventricular septal defect and Fallot tetralogy, and gastrointestinal abnormalities, such as Hirschsprung disease. Neurological and psychosocial developments are normal to mildly delayed, with the latter possibly being induced or aggravated by the common clinical sign of hearing loss.78 Case reports have shown that a considerable number of affected patients did not survive their newborn period,79 mainly because of severe airway obstruction complications.80 81 Most Nager syndrome patients appear to be sporadic, however, autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance has been reported as well. This led to the widespread speculation that Nager syndrome is genetically heterogeneous.

Nager syndrome shares many phenotypic features with TCS, but mandibular hypoplasia in Nager syndrome tends to be more severe. It can be distinguished from TCS by preaxial upper-limb deformities, such as thumb anomaly, radial defect, and radioulnar synostosis. Limb anomalies are a cardinal sign of Nager syndrome and, in combination with the characteristic facial features, are diagnostic. The presence of anterior upper-limb defects as opposed to posterior upper-limb defects and the typical lack of lower limb involvement distinguishes Nager syndrome from Miller syndrome, another rare AFD. Patients with Nager syndrome often have normal intelligence and do not show any evidence of cognitive deficiencies, which is different from the patients with MFDM.

By whole exome sequencing, the causative gene of Nager syndrome was identified to be SF3B4 (splicing factor 3B, subunit 4, OMIM 605593). SF3B4 encodes a spliceosome-associated protein 49 (SAP49), a component of the pre-mRNA spliceosomal complex, which is part of U2snRNP and is assumed to anchor U2snRNP to pre-mRNA during the splicing process (Table 4). SAP49 is a spliceosomal protein that is one of seven core proteins of the mammalian SF3B complex and is highly conserved with two RNA recognition motifs followed by a proline-glycine rich domain. During assembly of the U2SNP prespliceosomal complex, SAP49 binds to the pre-mRNA just upstream of the branch point sequence but also interacts specifically with other U2 snRNPs, particularly SAP145, suggesting that SAP49 plays a crucial role in tethering the U2 snRNP to the branch site.82 83 In addition to its role in mRNA splicing, SAP49 also specifically inhibit BMP-mediated osteochondral cell differentiation.84 This may contribute to the predominantly skeletal phenotype in Nager syndrome.

Table 4. List of SF3B4 mutations identified in patients with Nager syndrome (updated to 2014).

| Nucleotide change | Protein | Location | Predicted effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| c.2T > C | p.M1T | Exon 1 | Missense |

| c.1A > G | p.M1V | Exon 1 | Missense |

| c.88delT | p.W30Gfs*10 | Exon 2 | Frameshift |

| c.382C > T | p.Q128* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.452C > A | p.S151* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.546dupC | N/A | Exon 3 | Frameshift |

| c.574G > T | p.E192* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.577C > T | p.R193* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.661_664dupCCCA | p.N222Tfs*265 | Exon 3 | Frameshift |

| c.625C > T | p.Q209* | Exon 3 | Nonsense |

| c.671_674delTGGTinsCTCCCA | N/A | Exon 3 | Frameshift |

| c.737dupC | N/A | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.769delA | p.I257Yfs*63 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.796dupA | p.M266Nfs*220 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.817delC | N/A | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.827dupC | p.S277Ifs*209 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.836_837insGGGTATG | p.T280Gfs*208 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.864delT | p.H288Qfs*32 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.913 + 1G > A | N/A | Intron 4 | Splicing |

| c.914–1G > A | N/A | Intron 4 | Splicing |

| c.1006C > T | p.R336* | Exon 5 | Nonsense |

| c.1060dupC | p.R354Pfs*132 | Exon 4 | Frameshift |

| c.1147delC | p.H383Mfs*75 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1147dupC | p.H383Pfs*103 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1148dupA | p.H383Qfs*103 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1199delC | p.P400Lfs*58 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1229delC | N/A | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1232delC | p.P411Qfs*47 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

| c.1252_1258delCTTCGAG | p.L418Afs*38 | Exon 6 | Frameshift |

Abbreviation: N/A, not available.

Miller Syndrome

Miller syndrome, described in 197985 is a type of AFD, which is also referred to as Genée–Wiedemann, Wildervanck–Smith, or postaxial acrofacial dysostosis syndrome. It is a rare autosomal recessive disorder and is mainly characterized by malar hypoplasia, aplasia of the medial lower lid eyelashes, coloboma of the lower eyelid and cup-shaped ears, micrognathia, cleft lip, and/or palate combined with postaxial limb deformities, including apparent absence of either the fifth or both the fourth and fifth rays of the hands and feet, with or without ulnar and fibular hypoplasia. Normal intelligence was typical and internal malformations were rare.

Miller syndrome was the first Mendelian disorder whose molecular basis was identified via whole exome sequencing. Compound heterozygous mutations in DHODH gene (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, OMIM 126064), which encodes an enzyme required for de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis are responsible for Miller syndrome. The lack of homozygous mutations and the paucity of nonsense or frameshift alleles are unusual in a rare autosomal recessive disorder and suggest that the molecular mechanism underlying Miller syndrome is atypical. The fact that no individual has yet been indentified in which both alleles show severe loss of function suggests that such a combination may be lethal.

Generally, pyrimidine nucleotides are synthesized through two pathways: the de novo synthesis pathway and the salvage pathway. The enzyme DHODH catalyzes the fourth step in the de novo biosynthesis of pyrimidine by converting DHO (dihydro-orotate) into orotate. DHODH is also the only enzyme of this pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway that is located on the inner membrane of mitochondria, while all the other enzymes are located within the cytosol. DHODH catalyzes the oxidation of DHO to orotate by transferring electrons to the respiratory molecule ubiquinone through an enzyme-bound redox cofactor flavin mononucleotide. Thus, DHODH relies on ubiquinone, thereby forming a functional link between the mitochondrial respiratory chain and pyrimidine biosynthesis. DHODH has two binding sites. The substrate DHO binds to the first site and is oxidized via a cosubstrate electron acceptor. After the release of orotate, ubiquinone binds to a second site and receives an electron from the cosubstrate. The orotate synthesized by DHODH is converted into uridine monophosphate (UMP) by the enzyme complex UMPS (UMP synthase). These findings suggest that DHODH may affect mitochondria in neural crest cells. In situ analysis of mouse embryos showed DHODH is strongly expressed in the pharyngeal arch and limb bud, supporting a site and stage-specific requirement for de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Also, use of the DHODH inhibitor leflunomide during pregnancy causes a wide range of limb and craniofacial defects, the most common of which are exencephaly, cleft palate, and failure of the eyelid to close.86 However, recently, treatment of zebrafish with inhibitors of DHODH such as leflunomide, resulted in an almost complete abrogation of neural crest cell development principally by blocking the transcriptional elongation of critical neural crest cell genes.87 This suggests the cellular basis of Miller syndrome may lie in deficient neural crest cell formation and the failure to generate sufficient numbers of migrating neural crest cells, which is analogous to the pathogenesis of TCS. Furthermore, similar to TCOF1, DHODH has also been implicated in oxidative stress,88 suggesting there may be some considerable mechanistic overlap in the pathogenesis of Miller syndrome and TCS.

Genetic factors play a substantial role in the etiology of malocclusion,8 yet most conditions, however, are multifactorial. There is most likely a spectrum of influence that governs the ultimate shape of the upper and lower jaws. Some patients (and likely regions of bone) are more under genetic control, while the shape and size for others are determined more by environmental pressure. To correct anomalies caused more significantly by environmental pressure(s), these need to be addressed in conjunction with the orthodontic and/or surgical plan.

References

- 1.van der Linden F PGM. Genetic and environmental factors in dentofacial morphology. Am J Orthod. 1966;52(8):576–583. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(66)90138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angle E H. Philadelphia, PA: SS White Manufacturing Company; 1907. Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth: Angle's System. 7th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salzmann J A. Effect of molecular genetics and genetic engineering on the practice of orthodontics. Am J Orthod. 1972;61(5):437–472. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(72)90150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanner J M. “Nature and nurture”. In relation to growth and development. R Inst Public Health Hyg J. 1965;28(10):280–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston M C, Bronsky P T. Prenatal craniofacial development: new insights on normal and abnormal mechanisms. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6(4):368–422. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris J E. Genetic factors in the growth of the head. Inheritance of the craniofacial complex and malocclusion. Dent Clin North Am. 1975;19(1):151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. Class II Division 2 malocclusion: a heritable pattern of small teeth in well-developed jaws. Angle Orthod. 1998;68(1):9–20. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0009:CIDMAH>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markovic M D. At the crossroads of oral facial genetics. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14(6):469–481. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.6.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayram S, Basciftci F A, Kurar E. Relationship between P561T and C422F polymorphisms in growth hormone receptor gene and mandibular prognathism. Angle Orthod. 2014;84(5):803–809. doi: 10.2319/091713-680.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh G D, McNamara J A, Lozanoff S. Morphometric analyses of craniofacial morphology in patients with class III malocclusion. Clin Anat. 1996;9:3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidov S, Geseva N, Donveca T, Delhova L. Incidence of prognathism in Bulgaria. Dent Abstr. 1961;6:240. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascoe J J, Hayward J R, Costich E R. Mandibular prognathism: its etiology and a classification. J Oral Surg Anesth Hosp Dent Serv. 1960;18:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold J K A new approach to the treatment of mandibular prognathism Am J Orthod 19493512893–912., illust [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernex E, Hauenstein P, Roche M. Heredity and craniofacial morphology [in French] Rep Congr Eur Orthod Soc. 1967:239–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz S L, Osborne R H, DeGeorge F V. A cephalometric study of craniofacial variation in adult twins. Angle Orthod. 1960;30:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart R E, Spence M A. St. Louis, MO: CV Mosby Company; 1976. The genetics of common dental diseases; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stromeyer W. Die Vereburg des Hapsburger Familientypus. Nova Acta Leopold. 1937;5:219–296. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Susuki S. Studies on the so-called reverse occlusion. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1961;5:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulze C, Weise W. Zur vererburg der progenie. Fortschr Fte Kieferorthop. 1965;26:213–229. doi: 10.1007/BF02163505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watnick S S. Inheritance of craniofacial morphology. Angle Orthod. 1972;42(4):339–351. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1972)042<0339:IOCM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikuno K, Kajii T S, Oka A, Inoko H, Ishikawa H, Iida J. Microsatellite genome-wide association study for mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(6):757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Lu Y, Gao X H. et al. The growth hormone receptor gene is associated with mandibular height in a Chinese population. J Dent Res. 2005;84(11):1052–1056. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupu F, Terwilliger J D, Lee K, Segre G V, Efstratiadis A. Roles of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 in mouse postnatal growth. Dev Biol. 2001;229(1):141–162. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue F, Rabie A B, Luo G. Analysis of the association of COL2A1 and IGF-1 with mandibular prognathism in a Chinese population. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2014;17(3):144–149. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frazier-Bowers S, Rincon-Rodriguez R, Zhou J, Alexander K, Lange E. Evidence of linkage in a Hispanic cohort with a Class III dentofacial phenotype. J Dent Res. 2009;88(1):56–60. doi: 10.1177/0022034508327817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S W, Prockop D J, Helminen H. et al. Transgenic mice with targeted inactivation of the Col2 alpha 1 gene for collagen II develop a skeleton with membranous and periosteal bone but no endochondral bone. Genes Dev. 1995;9(22):2821–2830. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huh A, Horton M J, Cuenco K T. et al. Epigenetic influence of KAT6B and HDAC4 in the development of skeletal malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144(4):568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraft M, Cirstea I C, Voss A K. et al. Disruption of the histone acetyltransferase MYST4 leads to a Noonan syndrome-like phenotype and hyperactivated MAPK signaling in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(9):3479–3491. doi: 10.1172/JCI43428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vega R B, Matsuda K, Oh J. et al. Histone deacetylase 4 controls chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletogenesis. Cell. 2004;119(4):555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikopensius T, Saag M, Jagomägi T. et al. A missense mutation in DUSP6 is associated with Class III malocclusion. J Dent Res. 2013;92(10):893–898. doi: 10.1177/0022034513502790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C, Scott D A, Hatch E, Tian X, Mansour S L. Dusp6 (Mkp3) is a negative feedback regulator of FGF-stimulated ERK signaling during mouse development. Development. 2007;134(1):167–176. doi: 10.1242/dev.02701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, Li X, Zhang F, Chen F. The identification of a novel locus for mandibular prognathism in the Han Chinese population. J Dent Res. 2011;90(1):53–57. doi: 10.1177/0022034510382546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proetzel G, Pawlowski S A, Wiles M V. et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11(4):409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang J Y, Park E K, Ryoo H M. et al. Polymorphisms in the Matrilin-1 gene and risk of mandibular prognathism in Koreans. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1203–1207. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aszódi A, Bateman J F, Hirsch E. et al. Normal skeletal development of mice lacking matrilin 1: redundant function of matrilins in cartilage? Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(11):7841–7845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pichel J G, Fernández-Moreno C, Vicario-Abejón C, Testillano P S, Patterson P H, de Pablo F. Developmental cooperation of leukemia inhibitory factor and insulin-like growth factor I in mice is tissue-specific and essential for lung maturation involving the transcription factors Sp3 and TTF-1. Mech Dev. 2003;120(3):349–361. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suemori H, Noguchi S. Hox C cluster genes are dispensable for overall body plan of mouse embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2000;220(2):333–342. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opperman L A, Passarelli R W, Morgan E P, Reintjes M, Ogle R C. Cranial sutures require tissue interactions with dura mater to resist osseous obliteration in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(12):1978–1987. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkie A O. Craniosynostosis: genes and mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(10):1647–1656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.10.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mundlos S, Otto F, Mundlos C. et al. Mutations involving the transcription factor CBFA1 cause cleidocranial dysplasia. Cell. 1997;89(5):773–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixon M J Treacher Collins syndrome Hum Mol Genet 19965(Spec No):1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon J, Jones N C, Sandell L L. et al. Tcof1/Treacle is required for neural crest cell formation and proliferation deficiencies that cause craniofacial abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(36):13403–13408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603730103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morriss-Kay G M, Wilkie A O. Growth of the normal skull vault and its alteration in craniosynostosis: insights from human genetics and experimental studies. J Anat. 2005;207(5):637–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petit P, Moerman P, Fryns J P. Acrofacial dysostosis syndrome type Rodriguez: a new lethal MCA syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(3):343–345. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christianson A L, Kruger H, Dini L. Atypical acrofacial dysostosis syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;51(1):32–34. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wieczorek D. Human facial dysostoses. Clin Genet. 2013;83(6):499–510. doi: 10.1111/cge.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon C T, Weaver K N, Zechi-Ceide R M. et al. Mutations in the endothelin receptor type A cause mandibulofacial dysostosis with alopecia. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lines M A, Huang L, Schwartzentruber J. et al. Haploinsufficiency of a spliceosomal GTPase encoded by EFTUD2 causes mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luquetti D V, Hing A V, Rieder M J. et al. “Mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly” caused by EFTUD2 mutations: expanding the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(1):108–113. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voigt C, Mégarbané A, Neveling K. et al. Oto-facial syndrome and esophageal atresia, intellectual disability and zygomatic anomalies - expanding the phenotypes associated with EFTUD2 mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:110. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hedera P, Toriello H V, Petty E M. Novel autosomal dominant mandibulofacial dysostosis with ptosis: clinical description and exclusion of TCOF1. J Med Genet. 2002;39(7):484–488. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.7.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richieri-Costa A, Ribeiro L A. Macrostomia, preauricular tags, and external ophthalmoplegia: a new autosomal dominant syndrome within the oculoauriculovertebral spectrum? Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43(4):429–434. doi: 10.1597/05-060.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toriello H V, Higgins J V, Abrahamson J, Waterman D F, Moore W D. X-linked syndrome of branchial arch and other defects. Am J Med Genet. 1985;21(1):137–142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320210120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gorlin R J, Cohen M M, Levin L S. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1990. Syndromes of the Head and Neck. 3rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franceschetti A, Brocher J E, Klein D. Unilateral mandibulo-facial dysostosis with multiple skeletal deformities (paramastoïde process, vertebral synostosis, sacralization, etc.) and clonic torticollis [in French] Ophthalmologica. 1949;118(4–5):796–814. doi: 10.1159/000300779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teber O A, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Fischer S. et al. Genotyping in 46 patients with tentative diagnosis of Treacher Collins syndrome revealed unexpected phenotypic variation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12(11):879–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen J, Ghezzi F, Gonçalves L, Fuentes J D, Paulyson K J, Sherer D M. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of Treacher Collins syndrome: a case and review of the literature. Am J Perinatol. 1995;12(6):416–419. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowman M, Oldridge M, Archer C. et al. Gross deletions in TCOF1 are a cause of Treacher-Collins-Franceschetti syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(7):769–777. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beygo J, Buiting K, Seland S. et al. First Report of a Single Exon Deletion in TCOF1 Causing Treacher Collins Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2012;2(2):53–59. doi: 10.1159/000335545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Macaya D, Katsanis S H, Hefferon T W. et al. A synonymous mutation in TCOF1 causes Treacher Collins syndrome due to mis-splicing of a constitutive exon. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A(8):1624–1627. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isaac C, Marsh K L, Paznekas W A. et al. Characterization of the nucleolar gene product, treacle, in Treacher Collins syndrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(9):3061–3071. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dixon J, Brakebusch C, Fässler R, Dixon M J. Increased levels of apoptosis in the prefusion neural folds underlie the craniofacial disorder, Treacher Collins syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(10):1473–1480. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dauwerse J G, Dixon J, Seland S. et al. Mutations in genes encoding subunits of RNA polymerases I and III cause Treacher Collins syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011;43(1):20–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sakai D, Trainor P A. Treacher Collins syndrome: unmasking the role of Tcof1/treacle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(6):1229–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valdez B C, Henning D, So R B, Dixon J, Dixon M J. The Treacher Collins syndrome (TCOF1) gene product is involved in ribosomal DNA gene transcription by interacting with upstream binding factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones N C, Lynn M L, Gaudenz K. et al. Prevention of the neurocristopathy Treacher Collins syndrome through inhibition of p53 function. Nat Med. 2008;14(2):125–133. doi: 10.1038/nm1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sakai D, Dixon J, Dixon M J, Trainor P A. Mammalian neurogenesis requires Treacle-Plk1 for precise control of spindle orientation, mitotic progression, and maintenance of neural progenitor cells. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guion-Almeida M L, Zechi-Ceide R M, Vendramini S, Tabith Júnior A. A new syndrome with growth and mental retardation, mandibulofacial dysostosis, microcephaly, and cleft palate. Clin Dysmorphol. 2006;15(3):171–174. doi: 10.1097/01.mcd.0000220603.09661.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guion-Almeida M L, Vendramini-Pittoli S, Passos-Bueno M R, Zechi-Ceide R M. Mandibulofacial syndrome with growth and mental retardation, microcephaly, ear anomalies with skin tags, and cleft palate in a mother and her son: autosomal dominant or X-linked syndrome? Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A(12):2762–2764. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lines M A, Huang L, Schwartzentruber J. et al. Haploinsufficiency of a spliceosomal GTPase encoded by EFTUD2 causes mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Czeschik J C, Voigt C, Alanay Y. et al. Clinical and mutation data in 12 patients with the clinical diagnosis of Nager syndrome. Hum Genet. 2013;132(8):885–898. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luquetti D V, Hing A V, Rieder M J. et al. “Mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly” caused by EFTUD2 mutations: expanding the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(1):108–113. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson T L, Vilardell J. Regulated pre-mRNA splicing: the ghostwriter of the eukaryotic genome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(6):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gordon C T, Petit F, Oufadem M. et al. EFTUD2 haploinsufficiency leads to syndromic oesophageal atresia. J Med Genet. 2012;49(12):737–746. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nager F R, de Reynier J P. Das Gehoerorgan bei den angeborenen Kopfwissbildungen. Pract Otorhinolaryng. 1948;10:1–128. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin J L. Nager syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Neonatol. 2012;53(2):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McDonald M T, Gorski J L. Nager acrofacial dysostosis. J Med Genet. 1993;30(9):779–782. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.9.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Herrmann B W, Karzon R, Molter D W. Otologic and audiologic features of Nager acrofacial dysostosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(8):1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chemke J, Mogilner B M, Ben-Itzhak I, Zurkowski L, Ophir D. Autosomal recessive inheritance of Nager acrofacial dysostosis. J Med Genet. 1988;25(4):230–232. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.4.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Friedman R A, Wood E, Pransky S M, Seid A B, Kearns D B. Nager acrofacial dysostosis: management of a difficult airway. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;35(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groeper K, Johnson J O, Braddock S R, Tobias J D. Anaesthetic implications of Nager syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12(4):365–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bernier F P, Caluseriu O, Ng S. et al. Haploinsufficiency of SF3B4, a component of the pre-mRNA spliceosomal complex, causes Nager syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(5):925–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Champion-Arnaud P, Reed R. The prespliceosome components SAP 49 and SAP 145 interact in a complex implicated in tethering U2 snRNP to the branch site. Genes Dev. 1994;8(16):1974–1983. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Watanabe H, Shionyu M, Kimura T, Kimata K, Watanabe H. Splicing factor 3b subunit 4 binds BMPR-IA and inhibits osteochondral cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20728–20738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller M, Fineman R, Smith D W. Postaxial acrofacial dysostosis syndrome. J Pediatr. 1979;95(6):970–975. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fukushima R, Kanamori S, Hirashiba M. et al. Teratogenicity study of the dihydroorotate-dehydrogenase inhibitor and protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor Leflunomide in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(3–4):310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.White R M, Cech J, Ratanasirintrawoot S. et al. DHODH modulates transcriptional elongation in the neural crest and melanoma. Nature. 2011;471(7339):518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature09882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hail N Jr, Chen P, Kepa J J, Bushman L R, Shearn C. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase is required for N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced reactive oxygen species production and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]