Summary

Over one billion people worldwide are infected with parasitic nematodes. Many parasitic nematodes actively search for hosts to infect using volatile chemical cues, so understanding the olfactory signals that drive host seeking may elucidate new pathways for preventing infections. The free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a powerful model for parasitic nematodes: because sensory neuroanatomy is conserved across nematode species, an understanding of the microcircuits that mediate olfaction in C. elegans may inform studies of olfaction in parasitic nematodes. Here we review circuit mechanisms that allow C. elegans to respond to odorants, gases, and pheromones. We also highlight work on the olfactory behaviors of parasitic nematodes that lays the groundwork for future studies of their olfactory microcircuits.

Introduction

Nematodes comprise a large and diverse phylum of roundworms that includes both free-living and parasitic species. Parasitic nematodes of humans, livestock, and plants cause extensive disease and economic loss worldwide. The free-living nematode C. elegans has emerged as a model for the study of sensory neurobiology. C. elegans offers many advantages as a model system: it has a small and transparent body, making it possible to image neural activity in real time and to use behavior as a readout of circuit function. Its small nervous system consists of 302 neurons in the adult hermaphrodite and 385 in the adult male [1,2]. The connections among these neurons have been mapped, facilitating the identification of functional microcircuits [1–3]. Studies of the C. elegans connectome have shown that similar connectivity motifs are found in both C. elegans and mammalian cortex [3], suggesting that similar computational units operate across diverse taxa. Recent technical advances have made probing neural circuit function in intact animals feasible with the ability to induce and reversibly manipulate neural activity through genetics, pharmacology, light, and sound [4–7]. These advances have greatly expanded our knowledge of how olfactory microcircuits drive behavior and how these circuits are contextually modulated.

Different nematode species share conserved positional sensory neuroanatomy [8,9], and thus understanding how C. elegans microcircuits generate olfactory behaviors may have direct implications for how analogous microcircuits operate in parasitic nematodes. Although the microcircuits underlying olfactory preferences in parasitic nematodes are poorly understood, recent studies have elucidated the divergent olfactory preferences of different parasitic nematode species. Here we review the olfactory behaviors of free-living and parasitic nematodes, and highlight some of the microcircuit computations underlying olfactory behaviors in C. elegans.

Olfaction in C. elegans

Olfaction is an important sensory modality for C. elegans, enabling it to sense food, pathogens, predators, and conspecifics. Proliferating populations of C. elegans are found primarily in fallen rotting fruits, where oxygen (O2) concentrations are low [10]. When environmental conditions are unfavorable or food is scarce, C. elegans enters a developmentally arrested, alternative larval stage called the dauer. Dauers disperse into the soil to search for more favorable environments. Dauers are also phoretic, meaning that they associate with insect vectors that can transport them to more favorable environments [10]. These ecological niches inhabited by C. elegans inform the olfactory and gas-sensing strategies of the worm. Like other animals, C. elegans responds flexibly to odors and gases, modulating its behavior based on both internal and external contexts. The contextual modulation of olfactory behaviors allows worms to make appropriate behavioral decisions in their current environment.

The olfactory circuit of C. elegans consists of a small number of highly interconnected neurons, with an average of 3.5 synapses separating sensory neuron input from motor neuron output [2,3,11]. Using this circuit, C. elegans can sense and respond to at least 50 odorants [12]. C. elegans expands its coding capacity through dynamic modulation of neurons and microcircuits, including the use of neuromodulators and neuropeptides to create extrasynaptic functional connections between neurons [13]. The computations performed by the C. elegans olfactory circuit involve fundamental circuit motifs of neural networks and control systems (e.g. feedback inhibition and reciprocal inhibition), suggesting that the mechanisms by which C. elegans microcircuits functionally process sensory information and drive contextually appropriate behaviors may be conserved in other nervous systems [14].

Organization of the olfactory system

The primarily olfactory organs of C. elegans are the bilaterally symmetric amphid sensilla in the head. Eleven chemosensory neurons extend anterior processes with ciliated endings into each amphid sensillum [12]. In contrast to the olfactory sensory neurons of insects and mammals, those of C. elegans each express many different olfactory receptors. As in mammals, most of the olfactory receptors are seven transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptors [12]. Different pairs of olfactory sensory neurons generally drive attraction or avoidance: odor sensing by the AWA and AWC neurons promotes attraction, whereas odor sensing by the ASH, ADL, and AWB neurons promotes repulsion (Box 1) [12].

Box 1. Summary of functional properties of selected C. elegans chemosensory neurons.

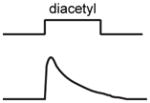

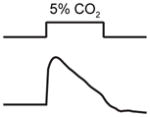

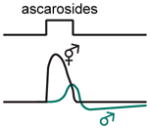

A non-exhaustive compilation of selected sensory neuron properties and their functional involvement in different microcircuits that are highlighted by this review. The “schematic of activity” depicts a representative shape of calcium activity of each sensory neuron to a particular stimulus that it senses. These traces were based off the following references: AWC [15], AWA [28], ASH [18], ADL [59], BAG [52]. The variable timescales by which these neurons respond to stimuli is not distinguished in our schematic. For BAG neurons, the trace depicts activity from the C. elegans adult. For ADL neurons, the male ADL response is shown in green and the hermaphrodite response is shown in black. The functional properties described were based off the following references: AWC [11,12,15,19–23,33], AWA [28,39], ASH [18,39], BAG [22,44,48,50,52–54], ADL [36,59].

The AWA olfactory neurons are “on-cells” that depolarize in the presence of odors, whereas the AWC olfactory neurons are “off-cells” that hyperpolarize in the presence of odors and depolarize upon odor removal [11,15–17]. AWB neurons show both “off” and “on” responses [11,16–18]. Each of these neurons has synaptic connections with other sensory neurons as well as downstream interneurons [3]. Whereas insect and mammalian sensory neurons are generally dedicated to one sensory modality, most C. elegans sensory neurons are polymodal as a consequence of the worm’s compact and highly interconnected nervous system. For example, the AWC neurons sense odors, temperature, salt, pH, CO2, and osmotic stress [11,19–22].

A circuit for olfactory attraction

The microcircuit that mediates olfactory attraction via the glutamatergic AWC neurons is the most well-characterized and involves at least three downstream interneurons – AIY, AIA, and AIB [15,23]. In response to the removal of an attractive odorant, AWC inhibits AIY and AIA via glutamate-gated chloride channels, and activates AIB via AMPA-type glutamate receptors. This organization of the olfactory microcircuit into parallel pathways with inverted polarities resembles that of the vertebrate retina, where photoreceptors synapse onto opposing ON and OFF bipolar cells [15]. The temporal dynamics of AWC neuron responses to on/off patterns of olfactory stimuli correspond to the timescales of AWC-mediated odor-evoked behaviors, suggesting that sensory neuron temporal dynamics instruct behavioral dynamics [24].

Navigational strategies for odor responses

To navigate through odor gradients, C. elegans primarily uses klinokinesis, also called a biased random walk, to modulate its turning rate and forward locomotion in response to its changing perception of odor concentration [12]. Worms either increase turns and decrease linear forward motion to reorient themselves away from their last (unfavorable) position, or suppress turns and increase forward motion to continue moving in the same (favorable) direction [12]. Manipulating the activity of first-order interneurons can mimic chemoattraction, suggesting that navigational strategy is determined at the level of the first-order interneurons [6]. By changing the polarity of klinokinesis in response to increasing and decreasing odor gradients, worms can shift their behavior from odor attraction to odor avoidance.

Mechanisms that determine odor valence

A number of mechanisms operate within the olfactory circuit to encode odor valence, i.e. whether an odor is attractive or repulsive. One mechanism involves a guanylate cyclase signaling pathway mediated by the receptor guanylate cyclase GCY-28, which acts in AWC sensory neurons to promote attraction to odors that AWC senses. Loss of gcy-28 switches AWC from a neuron that mediates attraction to one that mediates repulsion [25]. A similar switch from attraction to repulsion occurs in wild-type animals that are exposed to an odor that is initially attractive for a prolonged period in the absence of food [12,25], raising the possibility that gcy-28 signaling is part of a normal mechanism that flexibly alters odor valence based on environmental context. This study suggests that C. elegans olfactory sensory neurons are not irreversibly hard-wired for attraction or repulsion, but may in fact be more flexible in their responses than previously thought.

The valence of an odor stimulus can depend on its concentration. For example, low concentrations of the food-associated odorant isoamyl alcohol are attractive to C. elegans, while high concentrations are less attractive or even repulsive [18]. This valence change occurs because different sensory neurons mediate the response at different concentrations. At low concentrations the response is mediated primarily by the AWC olfactory neurons, while at high concentrations the response is mediated primarily by the ASH polymodal avoidance neurons (Box 1). The AWC response is blocked at high concentrations due to synaptic inhibition from other neurons [18]. A similar mechanism operates in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, where the behavioral response to apple cider vinegar shifts from attraction at low concentrations to repulsion at high concentrations due to the recruitment of additional glomeruli [26]. In both of these cases, odor valence is determined by which sensory neurons respond to the odor at a given concentration.

The valence of an odor stimulus can also depend on the presence of other sensory stimuli. First-order interneurons can modulate odor valence by integrating information about odor stimuli with information about other sensory stimuli to generate appropriate behaviors. For example, the AIA interneurons have been implicated in multisensory decision-making for behavioral cues with conflicting valences, such as the attractive odorant diacetyl and the aversive stimulus Cu2+ [27]. Multisensory decision-making is an important computation for evolutionarily stable nervous systems but occurs much earlier in C. elegans microcircuits (i.e. within one synapse of sensory input) than those of insects and mammals because the worm nervous system is so small and shallow. However, how first-order interneurons in worms integrate olfactory stimuli with other types of stimuli to drive appropriate behaviors remains poorly understood and is an active area of research.

Mechanisms of gain control and olfactory adaptation

Like other animals, C. elegans is capable of maintaining a dynamic range for sensing odors across concentrations that span several orders of magnitude. One mechanism for this involves rapidly attenuating sensory neuron responses and normalizing first-order interneuron responses [28]. Attenuation of the sensory neuron response prevents saturation, while normalization of the interneuron response results in a relatively concentration-invariant odor representation. The result is a microcircuit specialized for detecting small increases in odor concentration regardless of the absolute odor concentration. Similar mechanisms of odor coding operate in insects and vertebrates, where first-order interneurons in the olfactory circuit show normalized odor responses that encode odor identity regardless of concentration [29,30].

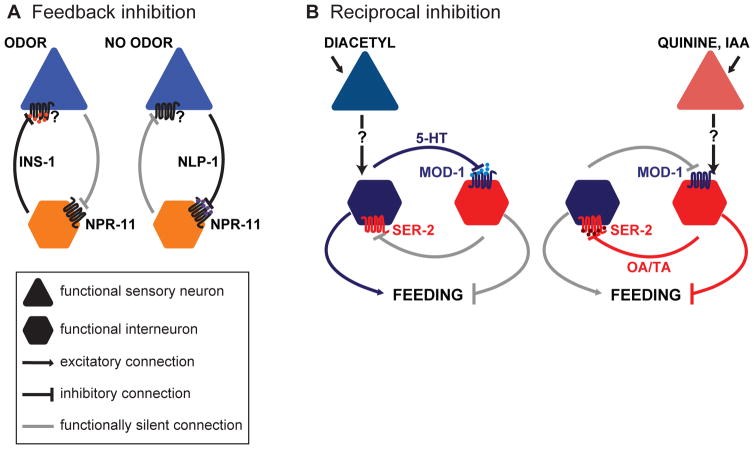

Another mechanism that may contribute to gain control is feedback inhibition from interneurons onto olfactory sensory neurons. For example, neuropeptide signaling between the AWC olfactory neurons and the AIA interneurons creates a feedback loop that promotes adaption to prolonged odor exposure and may also function as a gain control mechanism by dampening responses to strong odor stimuli (Figure 1A) [23]. Thus, both intracellular and circuit-level mechanisms are used to maintain odor responses across concentrations and promote adaption to prolonged odor exposures.

Figure 1. Models of microcircuit motifs present in the C. elegans olfactory system.

A. A feedback inhibition motif promotes odor adaptation and possibly gain control [23]. The AWC olfactory neurons release NLP-1, which binds NPR-11 on AIA interneurons to inhibit their activity. In the presence of an odor, AWC activity is suppressed. The resulting decrease in NLP-1 signaling permits AIA to release INS-1, which inhibits AWC through an unknown receptor [23]. B. Odor environment modulates feeding through a reciprocal inhibition motif [39]. The presence of attractive odors increases feeding, while the presence of repulsive odors decreases feeding. The attractive odorant diacetyl is sensed by the AWA neurons and causes serotonin (5-HT) release from the NSM neurons. 5-HT binds the serotonin-gated chloride channel MOD-1 on the RIM and RIC interneurons, which inhibits them and increases feeding. Repellents such as quinine or high concentrations of isoamyl alcohol (IAA) are sensed by the ASH neurons and promote release of octopamine (OA) and tyramine (TA) from RIM and RIC. OA and TA bind the SER-2 receptor on the NSM neurons and inhibit serotonin release [39].

Mechanisms that contribute to behavioral flexibility and variability

Olfactory responses in C. elegans are modulated by external and internal context, memory, sex, and life stage [12,16,31,32]. Multiple circuit mechanisms contribute to this behavioral flexibility. One mechanism involves modulation of chemoreceptor expression levels [31,32]. For example, sex, developmental stage, and feeding status alter expression of ODR-10, an odorant receptor in the AWA sensory neurons that detects the food-associated odor diacetyl [31]. Developing larvae of both sexes and starved adults express high levels of ODR-10, allowing them to find and remain in food. In contrast, adult males express low levels of ODR-10, allowing them to forego food in favor of locating mates [31]. By modulating the response properties of its sensory neurons, the worm can prioritize either food finding or mating in a context-appropriate manner.

In addition to showing context-dependent modulation of behavior, C. elegans shows stochasticity in its olfactory behavior. This behavioral variability stems at least in part from variability in interneuron responses: while sensory neuron responses are stereotyped, first-order interneuron responses are variable [33]. Interneuron response variability arises from the stochastic activity of multiple regulatory interneurons in the circuit; silencing these interneurons increases the reliability of first-order interneuron responses and reduces behavioral variability [33]. From an ecological perspective, behavioral variability is presumably advantageous at a population level: olfactory stimuli are often unpredictable, and behavioral variability increases the likelihood that at least some members of the population generate an appropriate behavioral response and survive.

Variability also occurs across populations as a result of genetic polymorphisms. For example, polymorphisms in the tyramine receptor TYRA-3, the neuropeptide Y receptor NPR-1, and the globin GLB-5 all cause population differences in foraging behavior and other chemosensory behaviors [32,34–38]. The behavioral differences that result from these polymorphisms demonstrate that the same olfactory circuit can drive a wide range of behaviors.

Interactions between the olfactory circuit and other sensory circuits

Olfactory signals can be integrated with other sensory stimuli to enhance or suppress behavioral responses. For example, pairing food with an attractive odor causes worms to eat more, whereas pairing it with an aversive odor causes worms to eat less [39]. Odors modulate feeding through a mutual inhibition circuit motif that relies on extrasynaptic neuromodulator signaling (Figure 1B). The increased feeding caused by attractive odors requires serotonin release from the NSM neurons. In contrast, the decreased feeding caused by aversive odors requires release of the neuromodulators octopamine and tyramine from the RIC and RIM interneurons. Serotonin and octopamine/tyramine bind receptors on RIC/RIM and NSM, respectively, and reciprocally block release of the other neuromodulator [39]. This reciprocal inhibition motif permits a bistable “winner take all” output from the circuit that either enhances or suppresses eating [39]. As a result, food intake in C. elegans is modulated based on the valence of associated olfactory stimuli, as it is in humans.

Olfactory sensory neurons can also participate directly in other sensory circuits to modulate non-olfactory behaviors. For example, in the presence of high salt concentrations one of the two AWC neurons is recruited as an interneuron into the gustatory circuit by the release of neuropeptides from the salt-sensing ASEL neuron and enhances attraction to salt [21]. By both responding to multiple types of stimuli and modulating behavioral responses to non-olfactory stimuli, olfactory neurons participate in multiple functional microcircuits. Dynamic regulation of these microcircuits through neuropeptide signaling expands the coding capacity of the C. elegans nervous system and allows the same neurons to be used for multiple functional microcircuits.

Circuits for learned avoidance of pathogenic bacteria

C. elegans displays associative olfactory learning: naïve worms that have never ingested the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 show either mild attraction or no preference for its odor, whereas worms that have ingested PA14 avoid it [17,40]. Learned avoidance of PA14 involves the RIA interneurons and two insulin-like peptides [41]. INS-7 released from the gas-sensing URX neurons increases the RIA response to PA14 and prevents worms from avoiding PA14. Antagonistically, INS-6 release from the ASI chemosensory neurons promotes learning by silencing signaling from URX onto RIA through the inhibition of ins-7 expression [41]. The ethological contexts in which insulin peptides regulate learning in wild-type animals remain to be determined.

Recently it was discovered that if C. elegans are exposed to PA14 early in development, olfactory imprinting occurs: worms form an aversive memory of the pathogenic bacteria that lasts into adulthood [42]. Separate microcircuits create and retrieve the memory, and transfer of the aversive memory from the formation microcircuit to the retrieval microcircuit involves tyraminergic signaling between the two circuits [42]. These examples of learned PA14 avoidance and aversive imprinting demonstrate that C. elegans is capable of learning on multiple timescales, and that learning on different timescales involves distinct circuit computations.

Microcircuits for gas-sensing behaviors

In addition to sensing volatile organic compounds, C. elegans senses oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). The natural habitat of C. elegans is fallen rotting fruit, where O2 levels are low [10]. Consistent with this, wild isolates of C. elegans prefer low O2 environments [43]. O2 is sensed primarily by the dedicated gas-sensing URX, AQR, PQR, and BAG neurons via soluble guanylate cyclases [43–46]. Variation in O2-evoked behaviors among C. elegans strains is due in part to polymorphisms in NPR-1 and GLB-5 [12,34,35]. The downstream circuitry for O2 response involves multiple interneurons, including RMG, AIY, AIA, AVB, and AVA [36,47]. High O2 environments are unfavorable and induce a global arousal state that is driven by the URX neurons and translated to other neurons in the circuit via the RMG interneurons [47]. This circuit architecture generates a long-lasting behavioral state in response to aversive high O2 environments that promotes rapid escape.

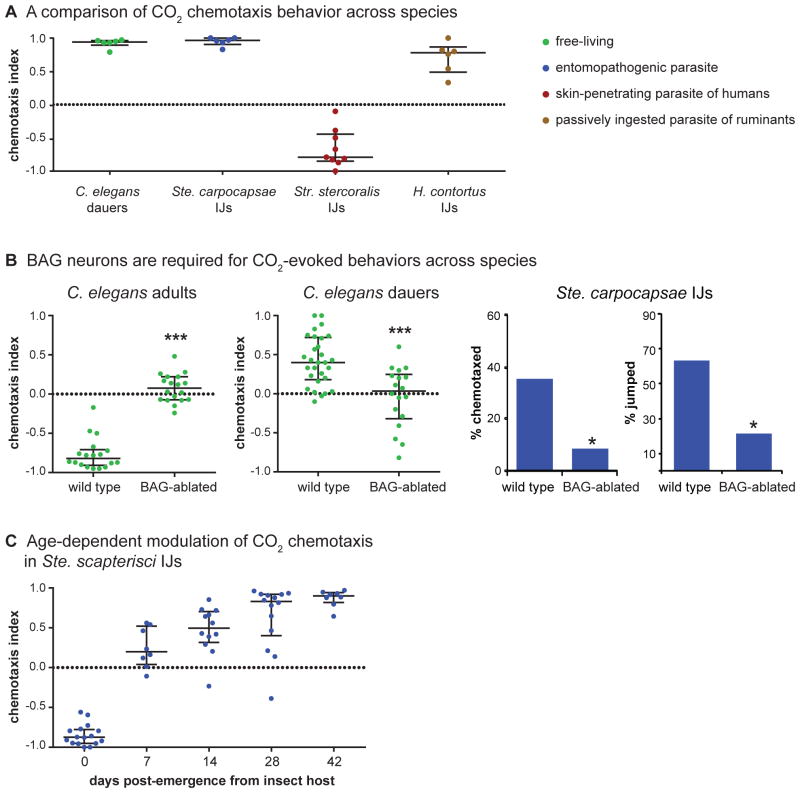

CO2 is a complex cue for C. elegans that may signal the presence of predators, conspecifics, or food. Well-fed C. elegans adults avoid CO2 both in the presence and absence of food [48,49]. However, CO2-evoked behavior is modulated by feeding status, salt, O2 environment, and temperature [37,38,48–50]. For example, CO2 response in adults is regulated by O2 environment through the O2-sensing URX neurons and NPR-1, such that the level of ambient O2 determines whether CO2 is perceived as aversive or neutral [37,38,48–50]. CO2 response also varies across life stages, with developmentally arrested dauer larvae showing CO2 attraction (Figure 2A) [51].

Figure 2. Diverse responses to CO2 across nematode species.

A. CO2 chemotaxis behavior varies across nematode species [84]. Phoretic C. elegans dauers, which seek insect vectors, entomopathogenic Ste. carpocapsae IJs, and passively ingested H. contortus IJs are attracted to CO2, while skin-penetrating Str. stercoralis IJs are repelled by CO2 [51,84]. Dauers and IJs were tested in a chemotaxis assay with 10% CO2, in which the animals were given 1 hr to migrate in a CO2 gradient. A positive chemotaxis index (CI) indicates attraction and a negative CI indicates repulsion. B. The BAG neurons are required for multiple CO2-evoked behaviors across species. Left, BAG neurons are required for CO2 chemotaxis in C. elegans adults and dauers regardless of whether CO2 is attractive or repulsive [37,51]. BAG-ablated C. elegans adults were tested in a 20 min assay [37], whereas dauers were tested in a 10 min assay [51]. Right, BAG neurons are required for both CO2 chemotaxis and CO2-evoked jumping in Ste. carpocapsae IJs [51]. The BAG neurons in IJs were laser-ablated; wild-type animals were mock-ablated. IJs were tested in either a 1 hr chemotaxis assay or a jumping assay in which IJs were given 8 s to jump in response to a 10% CO2 puff [51]. C. The response of Ste. scapterisci IJs to CO2 shifts from repulsion to attraction as the IJs age [90]. IJs were tested in a 1 hr chemotaxis assay with 1% CO2.

The microcircuits underlying CO2 response are incompletely understood. CO2 exposure alters the activity of many sensory neurons, although CO2 chemotaxis appears to be primarily mediated by the BAG and AFD neurons [22,37,38,48,50,52]. The BAG neurons are depolarized primarily by molecular CO2 rather than bicarbonate or low pH (Box 1) [53], and this response is mediated by the receptor guanylate cyclase GCY-9 [52,53]. The mechanisms of CO2 detection that operate in AFD and other CO2-sensing neurons have not been elucidated. The downstream circuitry that mediates CO2 chemotaxis is poorly understood, but both the RIA and AIA interneurons display CO2-evoked activity, implicating them in the CO2 microcircuit [22,38].

CO2 not only stimulates chemotaxis, but also inhibits egg-laying [22]. The CO2-induced inhibition of egg laying is mediated in part by the BAG and AWC sensory neurons [22,54]. This circuit presumably functions to prevent deposition of eggs in unfavorable environments. Through extensive modulation of the O2 and CO2 microcircuits, and interactions of these circuits with those driving related behaviors such as egg laying, C. elegans can efficiently position itself in favorable environments for feeding and reproduction.

Microcircuits for pheromone-sensing behaviors

The C. elegans population consists of both hermaphrodites and males, and C. elegans males display mating behaviors toward hermaphrodites. The attraction of males to hermaphrodites is an essential aspect of mating behavior, and involves both volatile pheromones of unknown molecular identity [55] and soluble small-molecule pheromones in the ascaroside family that also mediate dauer formation [56,57]. Male attraction to hermaphrodites is driven by a combination of ascarosides that synergistically promote attraction [56]. Different free-living and parasitic species release different blends of ascarosides, and the behavioral responses to ascarosides are species-specific [58].

Detection of ascarosides by C. elegans males is mediated by both male-specific and shared sensory neurons: the four male-specific CEM sensory neurons, as well as the shared ASK and ADL sensory neurons, contribute to pheromone response [36,56,59]. The CEM neurons are unusual in that they show stochastic functional heterogeneity in their ascaroside responses both within and between animals, which may contribute to their encoding of ascaroside concentration [60]. The AIA interneurons act downstream of the ASK sensory neurons to mediate ascaroside attraction [36,57].

While males are attracted to ascarosides released by hermaphrodites, other hermaphrodites are repelled. This sexual dimorphism is regulated by a push-pull circuit motif involving the ADL and ASK sensory neurons [59]. In hermaphrodites the ADL neurons promote ascaroside avoidance (Box 1), whereas in males the ADL neuron response is smaller and eclipsed by the ASK neuron response, which antagonizes ADL-mediated avoidance to promote attraction. This push-pull arrangement can generate opposite behavioral responses depending on the balance of activity between the attractive and repulsive arms of the microcircuit [59], thereby enabling sex-specific responses to the same pheromone.

In wild isolates of C. elegans, pheromones are not only important for mating but also promote aggregation behavior, in which worms cluster together in the low O2 environment found at the edges of a bacterial lawn. Aggregation is regulated by both O2 and pheromone environments [36]. Responses to O2 and pheromones are coordinated by a hub-and-spoke microcircuit motif. The RMG interneurons form the hub and sensory neurons form the spokes. RMG is connected to the spoke sensory neurons, including the O2-sensing URX neurons and the pheromone-sensing ASK neurons, by gap junctions. This hub-and-spoke arrangement enables a single interneuron to regulate a complex behavior involving multiple sensory modalities by coordinately modulating the activity of many different sensory neurons [36].

In summary, C. elegans has a small nervous system but expands its coding capacity through the use of neuropeptides and neuromodulators that dynamically alter microcircuit function and composition. These neuropeptides and neuromodulators complement the highly interconnected nature of the nervous system and allow neurons to simultaneously participate in multiple orthogonal microcircuits that all coordinately converge on motor neurons to produce contextually appropriate behaviors. Many of the computational mechanisms found in C. elegans are likely used by parasitic nematodes in the context of host-seeking behavior, as discussed below.

Olfaction in parasitic nematodes

Human-parasitic nematodes infect over one billion people globally and cause some of the most neglected tropical diseases [61]. These diseases occur predominantly in low-resource settings and result in reduced work productivity and decreased cognitive performance as a result of chronic morbidity [61]. In addition, parasitic nematodes of livestock and plants result in billions of dollars in economic and food losses each year [62]. Many parasitic nematodes have an environmental infective stage, called the infective juvenile (IJ) or infective third-stage larva (L3i) in the case of insect-parasitic and mammalian-parasitic nematodes, that actively searches for hosts to infect using olfaction in combination with other sensory modalities [9]. A better understanding of olfaction in parasitic nematodes could therefore lead to new strategies for preventing parasitic nematode infections.

A unique aspect of nematode neurobiology is conserved neuroanatomy: electron microscopy studies of anterior sensory anatomy have demonstrated that even distantly related species have approximately the same number of neurons located in roughly the same positions within the body [8,9]. In addition, laser ablation studies have demonstrated that sensory neuron function is often conserved across free-living and parasitic nematode species [9]. For this reason, studies of C. elegans olfaction can directly inform studies of olfaction in parasitic worms.

A number of recent technical advances with skin-penetrating nematodes in the genera Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides promise to greatly facilitate the study of parasitic nematode sensory neurobiology. These include the ability to generate transgenic nematodes by gonadal microinjection and the ability to conduct genome editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system [63]. In addition, RNAi has been used successfully with some parasitic nematodes [63,64]. These techniques will enable studies of the neurons and circuits underlying the host-seeking behaviors of parasitic nematodes.

Olfactory behaviors of entomopathogenic nematodes

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) in the genera Heterorhabditis and Steinernema are parasitic nematodes that infect and kill insects. They are sometimes referred to as “beneficial nematodes” due to their utility for insect biocontrol. EPN-infection of insects is also of interest as a model for harmful parasitic nematodes that infect humans. Like C. elegans, EPNs respond to a diverse array of insect odorants, plant odorants, and CO2 [51,65–71]. Attraction to plant odorants serves to draw EPNs to locations where their insect hosts feed, and in fact some of the plant odorants that attract EPNs are emitted in response to insect damage [71–74].

CO2 is a strong attractant for EPNs and is used in combination with both insect- and plant-emitted odorants to locate insect hosts (Figure 2A) [51,65,66,71]. Attraction of EPNs to the odors of live insects is greatly reduced or eliminated when CO2 is chemically removed, suggesting that CO2 is a critical host cue [65,67]. However, the relative importance of CO2 versus insect-specific odorants varies for different EPN species and different insect species [65].

The attractive response of EPN IJs to CO2 resembles that of C. elegans dauer larvae (Figure 2A) [51,65]. Parasitic IJs and C. elegans dauers are developmentally analogous life stages [75] that may also be behaviorally analogous: whereas IJs seek out hosts to infect, dauers seek out invertebrate carriers [10]. CO2 attraction by both IJs and dauers may serve the similar purpose of facilitating interactions with insects. CO2 also stimulates jumping, a specialized host-finding behavior exhibited by some EPN species in which the IJs propel themselves into the air [51,65]. Thus the same chemosensory cue, CO2, can stimulate both general and species-specific behavioral responses. As in C. elegans, the BAG neurons mediate CO2-evoked behaviors (Figure 2B), indicating that the neural basis of CO2 response is at least partly conserved across species regardless of whether CO2 is an attractive or repulsive cue [51].

Olfactory behaviors of plant-parasitic nematodes

Soil-dwelling plant-parasitic nematodes (PPNs) use the general cue CO2 in combination with plant-specific odorants to specifically target the roots of host plants [70,76,77]. For at least some species, the attractive response to CO2 may in fact be a response to low pH resulting from dissolved CO2 rather than to the CO2 itself [78]. Some of the plant root volatiles that attract EPNs also attract PPNs, suggesting that there is an ecological cost for the plant associated with the production of these volatiles [79].

Plants also release volatiles such as ethylene that modulate attraction of PPNs to their roots [80]. In addition, volatiles from nearby plants can modulate attraction of PPNs to host plants. For example, when intercropped with crown daisy, the tomato plant is protected from parasitism by the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita [81]. Crown daisy roots produce lauric acid, which is attractive for PPNs at low concentrations but repulsive at high concentrations [81], reminiscent of the concentration-dependent effects of isoamyl alcohol on C. elegans [18]. After attracting M. incognita to crown daisy root, lauric acid appears to disrupt chemotaxis behavior and infectivity by downregulating expression of the FMRFamide-related neuropeptide FLP-18 [81]. The intercropping of certain plants may be a nonhazardous alternative to artificial pesticides: intercropping decreases PPN-induced crop damage through the modulation of PPN chemotaxis behavior.

Olfactory behaviors of mammalian-parasitic nematodes

Mammalian-parasitic nematodes also respond to a chemically diverse array of odorants. The olfactory behaviors of the human-parasitic threadworm Strongyloides stercoralis are the most well-studied. Str. stercoralis infects approximately 100 million people worldwide and leads to chronic gastrointestinal distress; infections can be fatal for immunocompromised individuals [82]. Str. stercoralis is a soil-dwelling worm that infects primarily by penetrating the skin of the feet. As such, Str. stercoralis IJs are attracted to a number of human skin and sweat odorants [83,84]. For example, Str. stercoralis IJs are attracted to urocanic acid, a histidine metabolite found in mammalian skin that is enriched in the skin of the feet [83]. Many of the odorants that attract Str. stercoralis are also known mosquito attractants, suggesting that human-parasitic nematodes and mosquitoes may target humans using some of the same olfactory cues [84]. An exception is CO2, which is attractive for mosquitoes but repulsive for Str. stercoralis and other skin-penetrating nematodes (Figure 2A) [84,85]. CO2 is presumably not an effective long-range host cue for Str. stercoralis due to its route of infection since only very low levels of CO2 are emitted from human skin [84].

The only passively ingested mammalian-parasitic nematode whose olfactory behavior has been characterized in detail is Haemonchus contortus, a parasite of ruminants that is a major cause of livestock disease worldwide [86]. H. contortus IJs respond robustly to olfactory cues, but unlike skin-penetrating IJs, they are attracted to CO2 (Figure 2A) [84]. H. contortus is also attracted to grass odor [84]. Attraction to CO2 and grass may serve to direct H. contortus IJs toward the mouths of grazing animals, where they are more likely to be ingested.

Olfactory behaviors of the necromenic nematode Pristionchus pacificus

Olfactory behavior has also been studied in Pristionchus pacificus, a necromenic species that associates with beetles [87]. Necromenic nematodes do not kill their hosts, but rather wait for their hosts to die and then propagate on the host cadaver. As such, necromeny is often considered an evolutionary intermediate between free-living and parasitic life styles. P. pacificus is attracted to live beetles as well as beetle odorants, beetle pheromone, and plant odorants [87,88]. Olfactory preferences differ among wild P. pacificus strains and among closely related Pristionchus species, perhaps reflecting differences in their host preferences [87,88]. Natural variation in the responses of different P. pacificus strains to beetle pheromone is associated with the cGMP-dependent protein kinase gene egl-4 [89], raising the possibility that cGMP signaling contributes to host seeking in parasitic nematodes.

Parasite olfactory preferences exhibit context-dependent modulation

As is the case for C. elegans, the olfactory preferences of parasitic nematodes are context-dependent and flexible. For example, both EPN IJs and skin-penetrating IJs exhibit temperature-dependent olfactory plasticity: culturing IJs at different temperatures changes their odor preferences [90]. In the case of the EPN Steinernema carpocapsae, the response to 80% of the tested odorants changed as a function of their previous cultivation temperature. IJs are long-lived and can survive in the soil through multiple seasons. The volatiles emitted by both animals and plants change seasonally, and thus temperature-dependent modulation of olfactory behavior may enable IJs to locate hosts despite seasonal changes in volatile emissions [90].

Some parasitic nematodes also show age-dependent changes in their olfactory preferences [90]. For example, the EPN Steinernema scapterisci is initially repelled by CO2 but becomes attracted to CO2 as the IJs age (Figure 2C). This change in CO2-evoked behavior may reflect a change in host-seeking strategy: CO2 avoidance by younger IJs may cause them to disperse into the environment in search of new host niches with more available resources (a high cost but potentially high reward behavior), whereas CO2 attraction by older IJs may cause them to remain in the proximity of existing host niches (a low cost but lower reward behavior) [90].

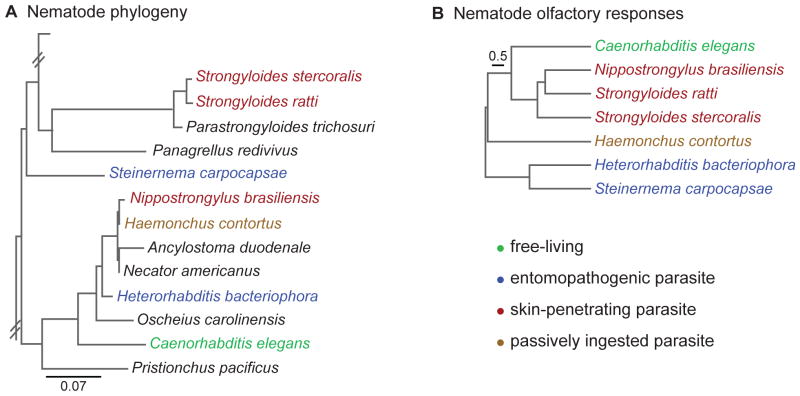

Odor preferences of parasitic nematodes are shaped by host specificity and mode of infection

A comparison of olfactory behavior across parasitic nematode species revealed that parasite olfactory preferences reflect host specificity and infection strategy rather than genetic relatedness, and that these parasite-specific preferences have evolved multiple times (Figure 3) [84]. For example, the skin-penetrating rat parasites Str. ratti and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis share similar odor preferences but are not closely related [84]. That odor preferences reflect parasite lifestyle rather than phylogeny suggests that olfaction plays an important role in the ability of parasitic nematodes to find and infect their hosts.

Figure 3. Olfactory responses of parasitic nematodes reflect their host ranges and infection modes rather than their genetic relatedness.

A. Schematic of phylogenetic relationships among nematode species [65,84]. Phylogenetic analysis is based on Castelletto et al., 2014 [84] and Dillman et al., 2012 [65]. B. A behavioral dendrogram of odor preferences among nematode species [84]. Species cluster based on the hosts they infect and their modes of infection, rather than their genetic relationships. For example, the skin-penetrating rat parasites Str. ratti and N. brasiliensis show similar odor preferences, even though they are not closely related genetically [84].

In summary, parasitic nematodes show species-specific olfactory behaviors despite the fact that sensory neuroanatomy is roughly conserved across nematode species [8,9]. Efforts to study olfactory neural circuits in parasitic nematodes are ongoing. Existing knowledge of sensory neuron function is based exclusively on laser ablation studies; the dynamics of sensory neural activity in parasitic nematodes have not been examined. Although the BAG neurons are the only olfactory neurons shown to have conserved function in parasitic and free-living worms [51], conserved sensory neurons also drive salt chemotaxis, thermotaxis, and changes in developmental stage in C. elegans and mammalian-parasitic worms [8,9]. Based on these studies, sensory neuron function appears to be broadly conserved across free-living and parasitic nematodes. In addition, the RIA interneuron plays a role in thermotaxis in both C. elegans and H. contortus [91], suggesting that interneuron function may be conserved in at least some cases. Nervous system connectivity has not yet been examined in parasitic nematodes. However, a recent study of the P. pacificus pharynx found that although P. pacificus and C. elegans share a set of 20 homologous pharyngeal neurons, the connectivity of these neurons differs in the two species [92]. Thus, behavioral differences among species may arise from a combination of altered connectivity of the nervous system, the actions of neuromodulators and neuropeptides, and species-specific differences in the functional properties of neurons. Future studies of olfactory circuits in parasitic nematodes should clarify the relative contribution of each of these factors to the evolution of olfactory neural circuits and odor-driven behaviors.

Conclusions

Recent studies of olfactory microcircuits in C. elegans have elucidated how the worm responds to odorants across a wide range of concentrations, and how these responses are modulated by environmental stimuli, internal behavioral state, and genotype. With new technical advances that enable nearly whole-brain imaging with single-neuron resolution in freely moving C. elegans [93–96], it should now be possible to determine how global changes in brain state alter olfactory microcircuits and to clarify the dynamics of how neurons are recruited into or omitted from these microcircuits.

Studies of olfactory behavior in parasitic nematodes have demonstrated how these parasites use olfactory cues to find and infect hosts, with implications for nematode control. Since molecular and genetic tools are now available for some parasitic worms, the microcircuits that drive these behaviors are at the cusp of discovery. Future studies comparing microcircuit function in C. elegans and parasitic nematodes should provide insight into how analogous microcircuits operate in free-living versus parasitic species to support parasite-specific olfactory behaviors.

Highlights.

C. elegans encodes complex olfactory behaviors with only a small number of neurons.

Microcircuit motifs that are fundamental across computational systems encode these behaviors.

Odor preferences of parasitic worms reflect their host ranges and infection mode.

Olfactory neuron function is at least partly conserved across nematode species.

| Box 1: Functions of selected chemosensory neurons involved in C. elegans microcircuits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuron: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Senses: | odors, temperature, CO2, salt, osmotic stress, pH | odors | odors, soluble chemicals, mechanical and osmotic stimuli | CO2, O2 | odors, pheromones |

Schematic of activity:

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Valence promoted: | attraction | attraction | avoidance |

avoidance

(adults) attraction (dauers) |

avoidance |

| Relevant interactions: |

|

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgments

We thank Astra Bryant, Michelle Castelletto, Albert Kao, Joon Ha Lee, Michelle Rengarajan, Sara Wasserman, and Kristen Yankura for insightful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the UCLA-Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program [T32GM008042], the UCLA Neural Microcircuit Training Grant [T32NS058280], and a predoctoral NRSA fellowship [1F30GM116810] to S.R.; and a MacArthur Fellowship, McKnight Scholar Award, NIH New Innovator Award [1DP2DC014596], and NSF grant [NSF IOS-1456064] to E.A.H.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Nothing declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sophie Rengarajan, Email: srengarajan@mednet.ucla.edu.

Elissa A. Hallem, Email: ehallem@ucla.edu.

References and recommended reading

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Emmons SW. Connectomics, the Final Frontier. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;116:315–330. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans Royal Soc London B. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varshney LR, Chen BL, Paniagua E, Hall DH, Chklovskii DB. Structural properties of the Caenorhabditis elegans neuronal network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1001066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibsen S, Tong A, Schutt C, Esener S, Chalasani SH. Sonogenetics is a non-invasive approach to activating neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8264. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang-Yen C, Alkema MJ, Samuel AD. Illuminating neural circuits and behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans with optogenetics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140212. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kocabas A, Shen CH, Guo ZV, Ramanathan S. Controlling interneuron activity in Caenorhabditis elegans to evoke chemotactic behaviour. Nature. 2012;490:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature11431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pokala N, Liu Q, Gordus A, Bargmann CI. Inducible and titratable silencing of Caenorhabditis elegans neurons in vivo with histamine-gated chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2770–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400615111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton FT, Li J, Schad GA. Chemo- and thermosensory neurons: structure and function in animal parasitic nematodes. Vet Parasitol. 1999;84:297–316. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gang SS, Hallem EA. Mechanisms of host seeking by parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2016;208:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix MA, Duveau F. Population dynamics and habitat sharing of natural populations of Caenorhabditis elegans and C briggsae. BMC Biol. 2012;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Zaslaver A, Liani I, Shtangel O, Ginzburg S, Yee L, Sternberg PW. Hierarchical sparse coding in the sensory system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1185–1189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423656112. In this study, the authors surveyed the responses of sensory neurons to a large panel of sensory stimuli and found that the C. elegans nervous system exhibits sparse coding (i.e. many stimuli only activate single classes of neurons) and functional hierarchy (i.e. some neurons respond to many more stimuli than others). This circuit organization may have evolved to expand the coding capacity of the worm’s small nervous system. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart AC, Chao MY. From odors to behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. In: Menini A, editor. The Neurobiology of Olfaction. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2010. edn 2011/09/02. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bargmann CI. Beyond the connectome: How neuromodulators shape neural circuits. Bioessays. 2012 doi: 10.1002/bies.201100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milo R, Shen-Orr S, Itzkovitz S, Kashtan N, Chklovskii D, Alon U. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science. 2002;298:824–827. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5594.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalasani SH, Chronis N, Tsunozaki M, Gray JM, Ramot D, Goodman MB, Bargmann CI. Dissecting a circuit for olfactory behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2007;450:63–70. doi: 10.1038/nature06292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Leinwand SG, Yang CJ, Bazopoulou D, Chronis N, Srinivasan J, Chalasani SH. Circuit mechanisms encoding odors and driving aging-associated behavioral declines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife. 2015;4:e10181. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10181. The response of adult C. elegans to the attractive odorant benzaldehyde declines with age. This study implicates four neurons in benzaldehyde attraction: two primary sensory neurons and two secondary neurons that receive input from the primary neurons. The authors elucidate a mechanism for the age-dependent decay in benzaldehyde attraction involving decreased responsiveness of the secondary but not primary neurons. The age-related behavioral decline was rescued by increasing synaptic output from the primary neurons, suggesting that age-related olfactory decline results from reduced neurotransmission in the circuit. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha HI, Hendricks M, Shen Y, Gabel CV, Fang-Yen C, Qin Y, Colon-Ramos D, Shen K, Samuel AD, Zhang Y. Functional organization of a neural network for aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron. 2010;68:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida K, Hirotsu T, Tagawa T, Oda S, Wakabayashi T, Iino Y, Ishihara T. Odour concentration-dependent olfactory preference change in C. elegans. Nat Commun. 2012;3:739. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biron D, Wasserman S, Thomas JH, Samuel AD, Sengupta P. An olfactory neuron responds stochastically to temperature and modulates Caenorhabditis elegans thermotactic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805004105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhara A, Okumura M, Kimata T, Tanizawa Y, Takano R, Kimura KD, Inada H, Matsumoto K, Mori I. Temperature sensing by an olfactory neuron in a circuit controlling behavior of C. elegans. Science. 2008;320:803–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1148922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leinwand SG, Chalasani SH. Neuropeptide signaling remodels chemosensory circuit composition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1461–1467. doi: 10.1038/nn.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Fenk LA, de Bono M. Environmental CO2 inhibits Caenorhabditis elegans egg-laying by modulating olfactory neurons and evokes widespread changes in neural activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E3525–3534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423808112. This study shows that the polymodal AWC neurons are CO2 sensors that modulate the egg-laying behavior of worms as a function of ambient CO2 levels. In high CO2 environments, which may be unfavorable to developing larvae, the AWC neurons are activated and suppress activity of the hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs), preventing deposition of eggs. These results demonstrate a mechanism for context-dependent modulation of behavior that may enhance reproductive fitness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalasani SH, Kato S, Albrecht DR, Nakagawa T, Abbott LF, Bargmann CI. Neuropeptide feedback modifies odor-evoked dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans olfactory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:615–621. doi: 10.1038/nn.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Kato S, Xu Y, Cho CE, Abbott LF, Bargmann CI. Temporal responses of C. elegans chemosensory neurons are preserved in behavioral dynamics. Neuron. 2014;81:616–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.020. By imaging the calcium activity of olfactory sensory neurons to fluctuating on/off sequences of odorants, the authors determine that the odor-evoked activity of these neurons acts on similar timescales to the behaviors the odors evoke. Disrupting the temporal dynamics of the olfactory sensory neuron responses disrupts behavioral dynamics. Thus, the behavioral responses to complex odor stimuli are guided by the temporal dynamics of the olfactory sensory neuron responses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsunozaki M, Chalasani SH, Bargmann CI. A behavioral switch: cGMP and PKC signaling in olfactory neurons reverses odor preference in C. elegans. Neuron. 2008;59:959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semmelhack JL, Wang JW. Select Drosophila glomeruli mediate innate olfactory attraction and aversion. Nature. 2009;459:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature07983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinkai Y, Yamamoto Y, Fujiwara M, Tabata T, Murayama T, Hirotsu T, Ikeda DD, Tsunozaki M, Iino Y, Bargmann CI, et al. Behavioral choice between conflicting alternatives is regulated by a receptor guanylyl cyclase, GCY-28, and a receptor tyrosine kinase, SCD-2, in AIA interneurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3007–3015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4691-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Larsch J, Flavell SW, Liu Q, Gordus A, Albrecht DR, Bargmann CI. A circuit for gradient climbing in C. elegans chemotaxis. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1748–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.032. This study identifies a mechanism for gain control that enables C. elegans to migrate toward attractive odorants across a wide range of concentrations. As odorant concentration increases, the olfactory sensory neuron attenuates its response, allowing it to remain sensitive to small increases in concentration. At the same time, the downstream interneuron normalizes its response to generate a mostly concentration-invariant signal. The result is a microcircuit capable of detecting small increases in odorant concentration across a wide range of absolute concentrations. This enables the worm to efficiently ascend an odor gradient. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsen SR, Bhandawat V, Wilson RI. Divisive normalization in olfactory population codes. Neuron. 2010;66:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu P, Frank T, Friedrich RW. Equalization of odor representations by a network of electrically coupled inhibitory interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1678–1686. doi: 10.1038/nn.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Ryan DA, Miller RM, Lee K, Neal SJ, Fagan KA, Sengupta P, Portman DS. Sex, age, and hunger regulate behavioral prioritization through dynamic modulation of chemoreceptor expression. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2509–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.032. This study demonstrates that modulation of odorant receptor expression contributes to context-dependent olfactory plasticity. The odorant receptor ODR-10, which detects the food odorant diacetyl, is expressed at lower levels in males than hermaphrodites, allowing males to forego food sources in favor of finding hermaphrodites. When males are starved, ODR-10 expression increases, allowing males to search for food. This mechanism enables males to prioritize either finding food or finding mates depending on current internal and external conditions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruner M, Nelson D, Winbush A, Hintz R, Ryu L, Chung SH, Kim K, Gabel CV, van der Linden AM. Feeding state, insulin and NPR-1 modulate chemoreceptor gene expression via integration of sensory and circuit inputs. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Gordus A, Pokala N, Levy S, Flavell SW, Bargmann CI. Feedback from network states generates variability in a probabilistic olfactory circuit. Cell. 2015;161:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.018. This study identifies a network mechanism that generates behavioral variability to an odorant despite reliable sensory neuron responses. Three interneurons are connected to each other through synaptic and electrical connections, resulting in the emergence of a network state. Although one of the interneurons has reliable odorant responses in isolation, feedback from the other interneurons promotes a probabilistic behavioral response. Behavioral variability is presumably adaptive given the complex and ambiguous nature of many olfactory stimuli. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson A, Gross E, Laurent P, Busch KE, Bretes H, de Bono M. Natural variation in a neural globin tunes oxygen sensing in wild Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2009;458:1030–1033. doi: 10.1038/nature07820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrath PT, Rockman MV, Zimmer M, Jang H, Macosko EZ, Kruglyak L, Bargmann CI. Quantitative mapping of a digenic behavioral trait implicates globin variation in C. elegans sensory behaviors. Neuron. 2009;61:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macosko EZ, Pokala N, Feinberg EH, Chalasani SH, Butcher RA, Clardy J, Bargmann CI. A hub-and-spoke circuit drives pheromone attraction and social behaviour in C. elegans. Nature. 2009;458:1171–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature07886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrillo MA, Guillermin ML, Rengarajan S, Okubo R, Hallem EA. O2-sensing neurons control CO2 response in C. elegans. J Neurosci. 2013;33:9675–9683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4541-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kodama-Namba E, Fenk LA, Bretscher AJ, Gross E, Busch KE, de Bono M. Cross-modulation of homeostatic responses to temperature, oxygen and carbon dioxide in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1004011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Li Y, Yi Y, Huang W, Yang S, Niu W, Zhang L, Xu Z, Qu A, Wu Z, et al. Dissecting a central flip-flop circuit that integrates contradictory sensory cues in C. elegans feeding regulation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:776. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris G, Shen Y, Ha H, Donato A, Wallis S, Zhang X, Zhang Y. Dissecting the signaling mechanisms underlying recognition and preference of food odors. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9389–9403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0012-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Hendricks M, Cornils A, Maier W, Alcedo J, Zhang Y. Two insulin-like peptides antagonistically regulate aversive olfactory learning in C. elegans. Neuron. 2013;77:572–585. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42**.Jin X, Pokala N, Bargmann CI. Distinct circuits for the formation and retrieval of an imprinted olfactory memory. Cell. 2016;164:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.007. This study demonstrates that first-stage C. elegans larvae exposed to pathogenic bacteria undergo imprinted aversion, resulting in long-lasting avoidance of the bactera. The authors show that different microcircuits underlie the formation and retrieval of this memory, and they implicate the biogenic amine tyramine in the transfer of learning from the formation to the retrieval microcircuit. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray JM, Karow DS, Lu H, Chang AJ, Chang JS, Ellis RE, Marletta MA, Bargmann CI. Oxygen sensation and social feeding mediated by a C. elegans guanylate cyclase homologue. Nature. 2004;430:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmer M, Gray JM, Pokala N, Chang AJ, Karow DS, Marletta MA, Hudson ML, Morton DB, Chronis N, Bargmann CI. Neurons detect increases and decreases in oxygen levels using distinct guanylate cyclases. Neuron. 2009;61:865–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Couto A, Oda S, Nikolaev VO, Soltesz Z, de Bono M. In vivo genetic dissection of O2-evoked cGMP dynamics in a Caenorhabditis elegans gas sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E3301–3310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217428110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung BH, Arellano-Carbajal F, Rybicki I, de Bono M. Soluble guanylate cyclases act in neurons exposed to the body fluid to promote C. elegans aggregation behavior. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1105–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Laurent P, Soltesz Z, Nelson GM, Chen C, Arellano-Carbajal F, Levy E, de Bono M. Decoding a neural circuit controlling global animal state in C. elegans. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04241. This study finds that high ambient oxygen levels promote a global arousal state that enhances efficient avoidance of the unfavorable environment. The oxygen-sensing URX neurons initiate this arousal state by stimulating neurpeptide release from the downstream RMG interneurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hallem EA, Sternberg PW. Acute carbon dioxide avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8038–8043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707469105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bretscher AJ, Busch KE, de Bono M. A carbon dioxide avoidance behavior is integrated with responses to ambient oxygen and food in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8044–8049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707607105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bretscher AJ, Kodama-Namba E, Busch KE, Murphy RJ, Soltesz Z, Laurent P, de Bono M. Temperature, oxygen, and salt-sensing neurons in C. elegans are carbon dioxide sensors that control avoidance behavior. Neuron. 2011;69:1099–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallem EA, Dillman AR, Hong AV, Zhang Y, Yano JM, DeMarco SF, Sternberg PW. A sensory code for host seeking in parasitic nematodes. Curr Biol. 2011;21:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hallem EA, Spencer WC, McWhirter RD, Zeller G, Henz SR, Ratsch G, Miller DM, Horvitz HR, Sternberg PW, Ringstad N. Receptor-type guanylate cyclase is required for carbon dioxide sensation by Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:254–259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017354108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith ES, Martinez-Velazquez L, Ringstad N. A chemoreceptor that detects molecular carbon dioxide. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:37071–37081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringstad N, Horvitz HR. FMRFamide neuropeptides and acetylcholine synergistically inhibit egg-laying by C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1168–1176. doi: 10.1038/nn.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leighton DH, Choe A, Wu SY, Sternberg PW. Communication between oocytes and somatic cells regulates volatile pheromone production in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:17905–17910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420439111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Srinivasan J, Kaplan F, Ajredini R, Zachariah C, Alborn HT, Teal PE, Malik RU, Edison AS, Sternberg PW, Schroeder FC. A blend of small molecules regulates both mating and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2008;454:1115–1118. doi: 10.1038/nature07168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srinivasan J, von Reuss SH, Bose N, Zaslaver A, Mahanti P, Ho MC, O’Doherty OG, Edison AS, Sternberg PW, Schroeder FC. A modular library of small molecule signals regulates social behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choe A, von Reuss SH, Kogan D, Gasser RB, Platzer EG, Schroeder FC, Sternberg PW. Ascaroside signaling is widely conserved among nematodes. Curr Biol. 2012;22:772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang H, Kim K, Neal SJ, Macosko E, Kim D, Butcher RA, Zeiger DM, Bargmann CI, Sengupta P. Neuromodulatory state and sex specify alternative behaviors through antagonistic synaptic pathways in C. elegans. Neuron. 2012;75:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60**.Narayan A, Venkatachalam V, Durak O, Reilly DK, Bose N, Schroeder FC, Samuel AD, Srinivasan J, Sternberg PW. Contrasting responses within a single neuron class enable sex-specific attraction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1392–1401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600786113. The CEM neurons are a male-specific class of sensory neurons in C. elegans that detect ascaroside pheromones and are involved in the attraction of males to hermaphrodites for the purpose of mating. Although the CEM neurons were previously thought to be functionally equivalent, the authors demonstrate stochastic functional heterogeneity of CEM neurons. Variation in the ascaroside responses of the CEM neurons of a single worm may arise from feedback inhibition between CEM neurons and may enable the worm to better encode ascaroside concentration. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boatin BA, Basanez MG, Prichard RK, Awadzi K, Barakat RM, Garcia HH, Gazzinelli A, Grant WN, McCarthy JS, N’Goran EK, et al. A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: towards control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jasmer DP, Goverse A, Smant G. Parasitic nematode interactions with mammals and plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052102.104023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lok JB, Shao H, Massey HC, Li X. Transgenesis in Strongyloides and related parasitic nematodes: historical perspectives, current functional genomic applications and progress towards gene disruption and editing. Parasitology. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ratnappan R, Vadnal J, Keaney M, Eleftherianos I, O’Halloran D, Hawdon JM. RNAi-mediated gene knockdown by microinjection in the model entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:160. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1442-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dillman AR, Guillermin ML, Lee JH, Kim B, Sternberg PW, Hallem EA. Olfaction shapes host-parasite interactions in parasitic nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2324–2333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211436109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Halloran DM, Burnell AM. An investigation of chemotaxis in the insect parasitic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Parasitol. 2003;127:375–385. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003003688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gaugler R, Campbell JF, Gupta P. Characterization and basis of enhanced host-finding in a genetically improved strain of Steinernema carpocapsae. J Invert Pathol. 1991;57:234–241. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson AF. Optimal release rates for attracting Meloidogyne incognita, Rotylenchulus reniformis, and other nematodes to carbon dioxide in sand. J Nematol. 1995;27:42–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koppenhofer AM, Fuzy EM. Attraction of four entomopathogenic nematodes to four white grub species. J Invert Path. 2008;99:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rasmann S, Ali JG, Helder J, van der Putten WH. Ecology and evolution of soil nematode chemotaxis. J Chem Ecol. 2012;38:615–628. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Turlings TC, Hiltpold I, Rasmann S. The importance of root-produced volatiles as foraging cues for entomopathogenic nematodes. Plant Soil. 2012;358:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rasmann S, Kollner TG, Degenhardt J, Hiltpold I, Toepfer S, Kuhlmann U, Gershenzon J, Turlings TC. Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature. 2005;434:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature03451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ali JG, Alborn HT, Stelinski LL. Subterranean herbivore-induced volatiles released by citrus roots upon feeding by Diaprepes abbreviatus recruit entomopathogenic nematodes. J Chem Ecol. 2010;36:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s10886-010-9773-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li C, Wang Y, Hua Y, Hua C, Wang C. Three dimensional study of wounded plant roots recruiting entomopathogenic nematodes with Pluronic gel as a medium. Biol Control. 2015;89:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crook M. The dauer hypothesis and the evolution of parasitism: 20 years on and still going strong. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farnier K, Bengtsson M, Becher PG, Witzell J, Witzgall P, Manduric S. Novel bioassay demonstrates attraction of the white potato cyst nematode Globodera pallida (Stone) to non-volatile and volatile host plant cues. J Chem Ecol. 2012;38:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reynolds AM, Dutta TK, Curtis RH, Powers SJ, Gaur HS, Kerry BR. Chemotaxis can take plant-parasitic nematodes to the source of a chemo-attractant via the shortest possible routes. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8:568–577. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang C, Bruening G, Williamson VM. Determination of preferred pH for root-knot nematode aggregation using pluronic F-127 gel. J Chem Ecol. 2009;35:1242–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10886-009-9703-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ali JG, Alborn HT, Stelinski LL. Constitutive and induced subterranean plant volatiles attract both entomopathogenic and plant parasitic nematodes. J Ecol. 2011;99:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fudali SL, Wang C, Williamson VM. Ethylene signaling pathway modulates attractiveness of host roots to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2013;26:75–86. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-12-0107-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81**.Dong L, Li X, Huang L, Gao Y, Zhong L, Zheng Y, Zuo Y. Lauric acid in crown daisy root exudate potently regulates root-knot nematode chemotaxis and disrupts Mi-flp-18 expression to block infection. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:131–141. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert356. Previous studies have shown that when tomato plants are intercropped with the crown daisy plant, the tomato plant is protected from parasitism by the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. This study identified a compound, lauric acid, in the crown daisy plant that attracts M. incognita at low concentrations and interferes with FMRFamide signaling to alter the parasite’s behavior and infectivity. By enhancing our understanding of how intercropping protects against plant-parasitic nematodes, these results could lead to new strategies for protecting crops without the use of pesticides. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mejia R, Nutman TB. Screening, prevention, and treatment for hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated infections caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:458–463. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283551dbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Safer D, Brenes M, Dunipace S, Schad G. Urocanic acid is a major chemoattractant for the skin-penetrating parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1627–1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610193104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84**.Castelletto ML, Gang SS, Okubo RP, Tselikova AA, Nolan TJ, Platzer EG, Lok JB, Hallem EA. Diverse host-seeking behaviors of skin-penetrating nematodes. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004305. This study showed that mammalian-parasitic nematodes respond to many odorants found in human skin and sweat. The study also showed that the odor preferences of parasitic nematodes are shaped by their host preferences and infection routes rather than their phylogeny, suggesting that odor preferences have evolved to complement parasitic behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chaisson KE, Hallem EA. Chemosensory behaviors of parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O’Connor LJ, Walkden-Brown SW, Kahn LP. Ecology of the free-living stages of major trichostrongylid parasites of sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2006;142:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McGaughran A, Morgan K, Sommer RJ. Natural variation in chemosensation: lessons from an island nematode. Ecol Evol. 2013;3:5209–5224. doi: 10.1002/ece3.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hong RL, Sommer RJ. Chemoattraction in Pristionchus nematodes and implications for insect recognition. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2359–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hong RL, Witte H, Sommer RJ. Natural variation in Pristionchus pacificus insect pheromone attraction involves the protein kinase EGL-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7779–7784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708406105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90*.Lee J, Dillman AR, Hallem EA. Temperature-dependent changes in the host-seeking behaviors of parasitic nematodes. BMC Biol. 2016;14:36. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0259-0. This study demonstrated that the odor preferences of parasitic nematodes are plastic and are shaped by age and cultivation temperature. These changes in olfactory behavior may enable the long-lived parasitic infective larvae to efficiently locate hosts despite seasonal changes in host-emitted or host-associated odors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li J, Zhu X, Boston R, Ashton FT, Gamble HR, Schad GA. Thermotaxis and thermosensory neurons in infective larvae of Haemonchus contortus, a passively ingested nematode parasite. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:58–73. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000814)424:1<58::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bumbarger DJ, Riebesell M, Rodelsperger C, Sommer RJ. System-wide rewiring underlies behavioral differences in predatory and bacterial-feeding nematodes. Cell. 2013;152:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Venkatachalam V, Ji N, Wang X, Clark C, Mitchell JK, Klein M, Tabone CJ, Florman J, Ji H, Greenwood J, et al. Pan-neuronal imaging in roaming Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1082–1088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507109113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Prevedel R, Yoon YG, Hoffmann M, Pak N, Wetzstein G, Kato S, Schrodel T, Raskar R, Zimmer M, Boyden ES, et al. Simultaneous whole-animal 3D imaging of neuronal activity using light-field microscopy. Nat Methods. 2014;11:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schrodel T, Prevedel R, Aumayr K, Zimmer M, Vaziri A. Brain-wide 3D imaging of neuronal activity in Caenorhabditis elegans with sculpted light. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1013–1020. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nguyen JP, Shipley FB, Linder AN, Plummer GS, Liu M, Setru SU, Shaevitz JW, Leifer AM. Whole-brain calcium imaging with cellular resolution in freely behaving Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1074–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507110112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]