Abstract

How myosin interacts with actin to generate force is a subject of considerable controversy. The major debate centers on understanding at what point in force generation the inorganic phosphate is released with respect to the lever arm swing, or powerstroke. Resolving the controversy is essential for understanding how force is produced as well as the mechanisms underlying disease-causing mutations in myosin. Recent structural insights on the powerstroke have come from a high-resolution structure of myosin in a previously unseen state and from an electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) 3D reconstruction of the actin-myosin-MgADP complex. We argue that seemingly contradictory data from time-resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) studies can be reconciled and we put forward a model for myosin force generation on actin.

Keywords: Molecular motors, Allostery, Force generation, Chemo-mechanical transduction

Force generation by molecular motors

Molecular motors generate movements and forces in cells. Understanding how they work as chemo-mechanical transduction machines is central to understanding how force generation powers critical and diverse cellular processes including contractile ring contraction during cell division, vesicle trafficking, organelle morphology and translocation, membrane deformation and the formation of actin protrusions important for migration, nerve growth and for specialized membrane protrusions such as microvilli and hair cells [1–4].

The cytoskeletal molecular motors, myosin, kinesin, and dynein, generate force and movement when they interact with their cellular tracks (actin filaments for myosin; microtubules for kinesin and dynein). In all cases, this force generation is powered by the hydrolysis of ATP and release of the hydrolysis products (inorganic phosphate and MgADP), which is coupled to structural changes associated with the track interactions. Among these cytoskeleton molecular motors, myosin has perhaps the best-documented principles of force production. However, the force generation mechanism triggered by F-actin binding, which includes the myosin powerstroke (see Glossary), is still poorly understood. In particular, the mechanism of force production cannot be described without gaining insights into the force producing states that control inorganic phosphate (Pi) release, ADP release, and movements of the myosin lever arm. There is considerable debate surrounding the interpretation of existing data that has led to conflicting models of myosin force generation. Here, we describe how recent structural and functional characterization of the powerstroke can be reconciled to provide a framework for understanding myosin force generation.

The Product Release Steps on Actin

After hydrolysis of ATP by myosin, force is produced upon sequential conformational changes of the motor triggered by rebinding to F-actin, which control and coordinate release of the hydrolysis products (Pi followed by MgADP) and force production. The key initial steps in the production of force by myosin-actin interactions are the release of Pi and the movement of the myosin lever arm. These steps are followed by the release of MgADP and an additional lever arm movement. New structural insights into how actin triggers the product release steps from myosin have come from two new myosin structures. The first is a high-resolution (1.75Å) structure of myosin VI in a previously unseen state [5]. The second structure is an electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the actin-myosin-MgADP complex (Strong ADP state; see Figure 1, Key Figure) at 8Å [6]. A 4Å resolution cryo-EM structure of the actin-myosin interface at the end of the powerstroke (Rigor state) has also been provided [7]. These studies provided new insights for resolving when the release of inorganic phosphate occurs with respect to the lever arm swing, or powerstroke, a central yet controversial aspect for the mechanism of force generation. The new X-ray structure was interpreted as the state that actin stabilizes to release phosphate, which was supported by mutagenesis and kinetic studies. However, other kinetic studies that observed the rates of the movement of the lever arm using Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) probes have been interpreted as demonstrating that the lever arm movement, or powerstroke, precedes the release of phosphate [8–10]. We discuss how the existence of a second Pi binding site may delay the detection of Pi in solution, and how the ability of a myosin activator to delay lever arm swing after Pi release, give rise to a unifying interpretation of the current data.

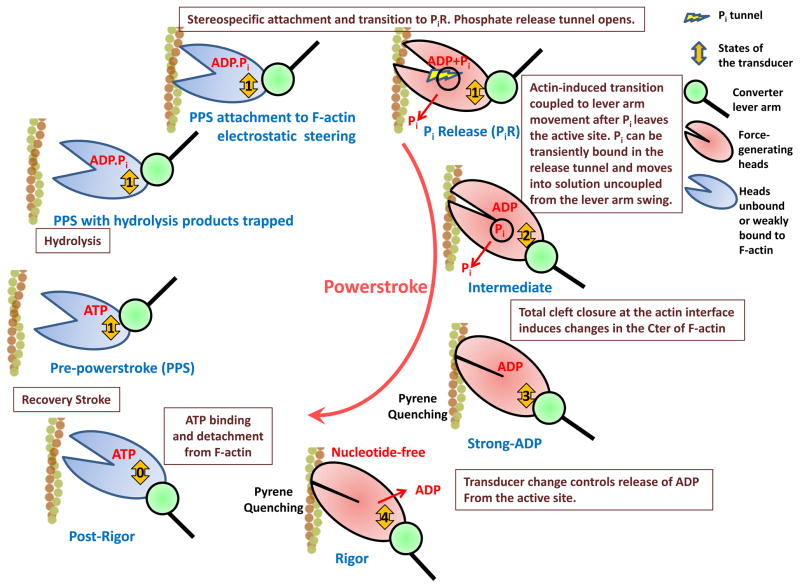

Figure 1. Key Figure.

Myosin force generation on actin filaments. Several structural states of the motor allow this molecular machine to generate force upon ATP hydrolysis. This scheme provides a unifying view of the current available structural and functional data available for this motor. The myosin heads are shown in red for states of the motor that produce force. This cycle describes the structural transitions during the powerstroke that actin promotes in the motor in order to sequentially release the hydrolysis products while directing a nanometer-long conformational change in the lever arm coupled to the swing of the converter (green).

Actin-myosin Kinetic Cycle and phosphate release

Myosin readily hydrolyzes ATP in the absence of actin, but rapid product release requires interaction with actin. Once Pi and MgADP have been released, ATP rapidly rebinds to the actin-bound myosin, causing fast dissociation from actin ([11]; Figure 1). While all forms of myosin have the same basic kinetic cycle, the rates of transition between the states are highly variable. This allows myosin to be “kinetically tuned” for a variety of cellular functions by not only altering the rate that it proceeds through the ATPase cycle, but also by changing the relative amount of the cycle that myosin spends in strong actin-binding (force generating) states, which is referred to as the duty ratio.

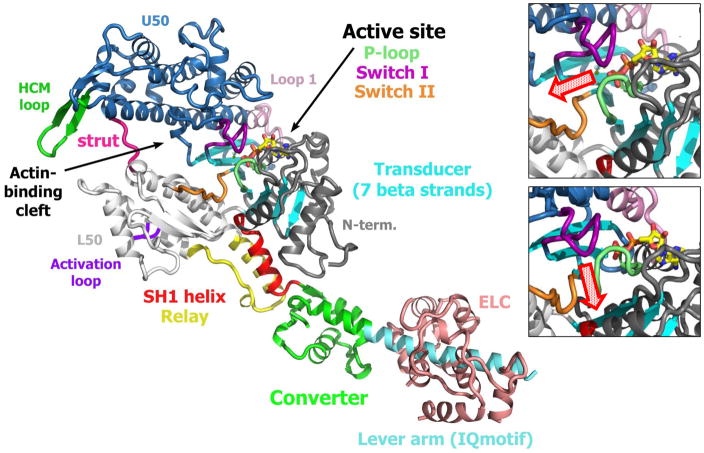

The initial interactions of myosin with actin trigger inorganic phosphate (Pi) release and force generation. In the absence of actin, Pi release is quite slow since myosin traps the Pi in the pre-powerstroke state. The control of Pi release by the motor is key for force generation: its presence and location in the motor controls the conformations myosin can explore while bound to F-actin. Soon after the publication of the initial myosin structure [12], it was noted that in order for actin-activated phosphate release to precede ADP release, actin would likely need to create an alternative escape route for phosphate rather than the normal exit through the nucleotide-binding pocket [11,13], which is blocked by MgADP. This “back door” mechanism is widely accepted, and there has been much speculation as to the nature of the back door [11,14]. What is clear is that in order for the phosphate to dissociate, there must be some rearrangement in one of two loops surrounding the phosphate binding site (namely switch I or switch II; See Figure 2). These elements, along with MgADP, block any possible dissociation of Pi from the pre-powerstroke state (PPS), which is the state that primes the lever arm position for the powerstroke on actin. This PPS state does not bind strongly or with stereo-specificity to actin, and thus is not a force-generating state.

Figure 2.

Myosin motor domain. A ribbon diagram of the myosin V motor illustrates components of the myosin motor domain including the four subdomains (U50, L50, N-term., and Converter) that move relative to each other during the structural transitions of the myosin force-generating cycle on actin. The subdomains are linked by flexible connectors (Switch II, Relay, SH1 helix, strut). ATP is bound to the switch elements (Switch I and Switch II) and P-loop of the active site. The actin-binding site is composed of actin-binding loops (such as the HCM loop and activation loop) from both the upper (U50) and lower (L50) 50-KDa subdomains that are separated by the actin-binding cleft, as well as a helix-loop-helix region of the lower 50-KDa (L50) subdomain. The Switch II connector (orange), situated close to the position where the γ-phosphate of ATP is bound, is found at the other end of this actin-binding cleft compared to the actin-binding site. The central β-sheet plays a critical role in closing the cleft during the powerstroke on actin and is part of the transducer region (cyan). A switch II (orange) movement creates a tunnel to release phosphate at the beginning of the powerstroke.

For many myosins, the initial actin interactions of the PPS state that lead to Pi release is highly dependent on ionic strength, leading to a slow apparent rate of Pi release at ionic strengths greater than a few mM. This likely reflects the need for electrostatic steering, involving charged loops on the myosin surface that orient the myosin with respect to the highly charged surface of actin. Unconventional myosins, such as myosin V and VI, are much less sensitive to ionic strength than are sarcomeric myosins [15]. However, after stereospecific binding to F-actin, the rate of Pi release per se is likely to be fast for all myosins [5]. It is thought that the weak, non-specific electrostatic binding of the PPS state by surface loops to actin allows the myosin to explore the actin surface until stronger, stereo-specific interactions can be made, and in doing so, actin promotes a myosin transition to a state that binds to actin with an altered actin interface and force generation is initiated [11].

A putative phosphate release (PiR) state structure (derived from a myosin VI crystal in the absence of actin) was published that has all of the hallmarks of what is needed for the first force-generating myosin state [5]. A switch II movement has occurred that opens a tunnel from which Pi can leave the nucleotide-binding pocket. However, this switch II movement occurs with minimal movement of the lever arm, and thus the initial rate of interaction would have minimal dependence on strain. Importantly, while the actin-binding cleft and interface have been altered as compared to PPS, presumably to facilitate stereo-specific binding to actin, the cleft is still open. This would allow the major lever arm swing to be coupled to closure of the actin-binding cleft to follow formation of the PiR state [11]. Once Pi leaves the nucleotide pocket, rapid closure of the actin-binding cleft, coupled to a major component of the powerstroke (lever arm swing) could occur. Note that the transition from the PPS state to the PiR state must also occur in the absence of actin and may account for the low basal ATPase activity of myosin. However, in the absence of actin the equilibrium must greatly favor the PPS state.

While the proposed phosphate release (PiR) state was crystallized in the absence of actin, mutagenesis/kinetic studies using myosin II, V, and VI mutants provides strong evidence that this state represents the PiR state that is formed on actin. Mutations in the release tunnel alter the actin-activated Pi release rate. Additional kinetic studies showed that Pi release precedes complete closure of the actin-binding cleft, as monitored by a pyrene probe on actin (see below). Thus, actin triggers the transition from the PPS state to this PiR state to initiate force generation and Pi release. The PiR state would then be followed by actin-binding cleft closure, and the powerstroke on actin [5].

It was shown that within the PiR crystals, phosphate can re-enter and bind within the tunnel, and that the presence of Pi in the active site promotes the formation of the pre- powerstroke state (PPS). A key observation of these studies is that once the Pi leaves the nucleotide-binding pocket, it can transiently stay at the mouth of the phosphate release tunnel (coordinated by T197 and R205 in myosin VI). This implies that there may be a delay between the time that phosphate leaves the active site, allowing the cleft to close, and when the phosphate appears in solution.

Rapid lever arm swing in the absence of load

Interpretation of this structure as the true phosphate release state has been called into question by a series of FRET studies that monitor the movement of the lever arm following myosin attachment to actin [8–10]. The debate centers on whether the powerstroke gates phosphate release or whether phosphate release gates the powerstroke. The FRET studies demonstrate that there is a rapid transition within the motor domain that affects the lever arm position. This transition is faster than the measured rate of phosphate release, and is followed by a slow lever arm movement that precedes ADP release. These data have been interpreted as showing that the large component of the lever arm swing occurs in the first rapid transition and precedes Pi release. These FRET studies conflict with the published Pi release (PiR) structure. In the structure, the lever arm is in a primed position, close to the position observed in the PPS state. In contrast to the proposed interpretation of the FRET studies, the PiR structure implies that Pi release from the active site would precede the powerstroke.

In a FRET study with myosin V [9], the results were similar to those earlier seen with myosin II [10]. Upon actin binding, there was a rapid lever arm movement (>300/sec) that was followed by a slower lever arm movement (~20/sec), while phosphate release was observed at ~200/sec. Again, since the measured rate of phosphate release was slower than the initial phase of the powerstroke, it was suggested that the powerstroke gates Pi release.

As noted above, PiR structures were obtained in which phosphate has moved away from the nucleotide-binding pocket, but is found bound at the mouth of the proposed phosphate release tunnel [5]. In this position, the phosphate likely will not restrict the structural rearrangements that may be necessary to close the actin-binding cleft and initiate the powerstroke, but the phosphate would not yet be detectable in solution. Since the transition from PPS to PiR and the next transition that is coupled to the initial phase of the powerstroke may both be extremely rapid in the absence of load, phosphate may not be detected in solution prior to when the rapid component of the powerstroke has been completed. To summarize, once Pi leaves the active site and moves into the release tunnel it can be transiently bound to a second binding site before appearing in solution, which is not coupled to the powerstroke (see Figure 1). This apparent lag in Pi release would be consistent with what has been observed [8–10]. In other words, it is formation of the phosphate release state and phosphate leaving the active site that gates the powerstroke, not the entry of phosphate into solution.

Lever arm swing follows Pi translocation

A drug that could stabilize the phosphate release state on F-actin and slow the next transition associated with the initial phase of powerstroke would provide further evidence for this hypothesis. We propose that omecamtiv mecarbil (OM), which is a small molecule that has been developed to increase cardiac force production [16], is such a drug. Kinetic analyses [17] reveal that this drug, which accelerates phosphate release upon cardiac myosin rebinding to F-actin, does so by stabilizing a force generating state that is prior to the ADP release step. OM was shown to stabilize the pre-powerstroke state, increasing the equilibrium constant of the hydrolysis step [17]. Given the structural similarities between the PPS state and the PiR state, it is likely that OM can bind both with similar affinities and will likely stabilize both states. This would lead to the observed accelerated phosphate release in the presence of actin, since the drug would cooperate with actin in promoting and stabilizing the PiR state. The rate of the large movement associated with the initial phase of the powerstroke would be slowed if it follows formation of the PiR state, even though the rate of phosphate release may be increased. Evidence that OM has this effect on cardiac myosin has recently been presented [18]. The authors, using a similar FRET approach as in their work described earlier in this article, observed a slowing of the powerstroke movement in the presence of OM, to the extent that it was slower than the rate of phosphate release, which was increased. While it could be proposed that OM manifests its effects by favoring a parallel pathway in which phosphate is released prior to the lever arm swing, this seems unlikely given that there is a simple kinetic explanation of the OM effect that would not require a parallel set of different structural changes in the myosin to be induced by OM.

This generalized concept of the lever arm swing following phosphate release fits well with fiber studies that suggest that the phosphate release step is only reversible if the myosin lever arms are pulled back to, or held at, a position near the beginning of the powerstroke [19]. Likewise, single molecule studies with skeletal myosin II and myosin V undergoing rapid feedback to counter movement led to the same conclusion [20–21]. The rapidity of the transition from PiR to initiation of closure of the actin-binding cleft in the absence of load may essentially rectify the transition, by closing the phosphate tunnel so that phosphate cannot reenter the nucleotide-binding pocket.

Generation of Force and Movement

While the lever arm movement is a major part of the force generating mechanism, force generation should be initiated before the lever arm moves, as a result of the first stereo-specific binding of myosin to actin. As first proposed by A.F. Huxley in 1957 [22], such binding constitutes a Brownian ratchet [23], and generates an immediate force upon attachment of myosin to actin, since the myosin attachment rectifies thermal motion. Huxley and Simmons later appreciated that this mechanism cannot explain the force transients generated by muscle fibers subjected to small but rapid changes in fiber length [24], unless there are additional movements of the myosin cross-bridges once they are tightly bound to actin. Based on our current structural knowledge, these additional movements can be interpreted as the powerstroke of myosin on actin. Huxley and Simmons noted that the movement that follows the attachment of myosin to actin must be comprised of multiple components. Recent models that best recapitulate the properties of contracting muscle require four distinct force-generating states [25], consistent with the model of Huxley and Simmons.

In the absence of any external load, all the force generated from the succession of force-generating transitions results in movement. With an external load applied, the velocity of this movement is slowed and the force produced against the load by myosin can be measured. When the external load exceeds the force produced by myosin, there is no net movement and maximal force is generated. However, since there is compliance within the myosin molecule, some of the force is dissipated by stretching internal springs, which also allows the myosin to proceed (at a much slower rate) through its ATPase cycle on actin in the absence of a net movement.

Cleft closure and lever arm swing

The current structural evidence suggests that the lever arm swing itself involves at least two components, with the release of MgADP following the final component of the swing [26–27]. In the past, the signal coming from pyrene actin has been interpreted as reporting cleft closure, which has been postulated to be coupled with movement of the lever arm. It also indicates that myosin must alter the conformation of F-actin, perhaps as the cleft fully closes while maintaining strong interactions at the actin interface, which is then transmitted to the pyrene probe on C-terminal sequence of actin. Stabilization of the C-terminal sequence of actin upon myosin binding in the rigor state is consistent with this proposal [7], as is the change in the F-actin helical repeat observed with CryoEM studies of strongly bound acto-myosin states (Strong MgADP and Rigor) [6]. However, the primary lever arm movement sensed by FRET experiments is much faster than the movement sensed by pyrene-actin, and furthermore there is not a large lever arm movement observed at the rate of pyrene quenching in optical trap experiments [28] or in the FRET experiments [8–10]. Thus, the initial powerstroke is rapid in the absence of load, and is followed by a slower structural transition that is sensed by the changes in pyrene actin. This may imply that the initial phase of the powerstroke is coupled to a partial cleft closure, and that additional cleft closure requires actin structural alterations in order to form the Strong ADP state (Figure 1). This final cleft closure may be coupled to a small lever arm swing. Whatever these actin changes are that are sensed by pyrene-actin, they appear to be associated with a small alteration in the actin helical twist, at least in the case of myosin V, as was seen in cryo-EM reconstructions [6].

MgADP release

At the end of the powerstroke, MgADP coordination is lost during the transition to the nucleotide-free conformation of myosin on actin, which is known as the rigor conformation, by relieving the strain in the seven-stranded beta sheet, allowing switch I and the P-loop to be sufficiently separated to lose MgADP coordination [29–30]. The Mg2+ dissociates first [31–32], while the ADP can transiently remain bound to the P-loop before its dissociation from the rigor state [33]. What is unclear is the nature of the structural state immediately prior to MgADP release. This is a state that binds MgADP strongly and simultaneously binds strongly to actin. The existence of this state was unsuspected until it was seen using cryo-EM for both smooth muscle myosin II and for brush border myosin I [26–27]. However, since there is very little free energy change associated with MgADP release, there is little change in force and additional work contributed by the final component of the lever arm swing. In fact, the main function of this movement appears to be the creation of strain-dependent prolongation of myosin attachment to actin (28), rather than an additional component of power generation.

The structural details of this state are not yet available at high-resolution, but a recent lower resolution EM structure has provided some new insights [6]. The EM structure demonstrated a different conformation of the beta-sheet, and elements of a structural motif that is known as the transducer [33], as compared to earlier structures. The P-loop has moved as a result of this structural shift, and the MgADP would appear to be coordinated in a somewhat different manner than is seen for either MgATP or MgADP in the myosin post-rigor state, populated when nucleotide is bound in the absence of actin [6]. This may result in weakening of the Mg2+ coordination, as Mg2+ has been shown to dissociate prior to ADP, and increasing [Mg2+] can slow ADP release [31–32]. The movement of the lever arm appears to be accomplished by novel positions of switch II, the relay and the SH1 helix (linked to the transducer conformation), which specify the converter and lever arm positions.

Actin-myosin Interface

A recent CryoEM structure revealed with unprecedented resolution how F-actin interacts with myosin at the end of the powerstroke (rigor) [7], but there is no actin-myosin structure available to describe how myosin interacts with F-actin during the earlier steps of force generation. Kinetic studies have revealed the role of a loop on the L50K subdomain (the activation loop; Figure 2) in promoting Pi release [5,34] indicating that the L50 subdomain of the PiR state must be part of the interface of this first force-generating state [5]. However, this loop is remote from F-actin in the rigor state [7], supporting a mechanism in which formation of a sub-set of bonds found in the rigor interface occurs prior to cleft closure [5, 7], and there is formation of new bonds involving loops of the U50 subdomain to strengthen the actin-myosin interface upon cleft closure.

Model for force generation

We propose a model in which the first step in force generation by myosin is the stabilization of the PiR state by actin binding, which produces force and allows Pi to leave the active site of myosin. We postulate that Pi at the active site creates a large thermodynamic barrier to actin-induced closure of the actin-binding cleft. The translocation of Pi away from the active site into the phosphate release tunnel, where it is bound at the mouth of the tunnel, greatly lowers the energy barrier and allows actin to rapidly induce cleft closure. Closure of the actin-binding cleft increases the number of interactions with actin (some of the PiR interactions, such as with the activation loop, may be lost in this process), and is coupled to the large movement (powerstroke) of the myosin lever arm. This rapid closure of the cleft coupled to lever arm movement closes access to the nucleotide-binding pocket by closing the phosphate tunnel and destroying the phosphate binding site at the mouth of the tunnel (as evidenced by the fact that they do not exist in the Rigor state structures). This would drive the reaction forward into the next force generating state. (If strain is imposed on the myosin as the PiR state forms, as in isometric contraction, actin-binding cleft closure may be delayed, allowing the phosphate release tunnel to remain open.) Thus, it is not the release of phosphate into solution that gates the powerstroke, rather the gating event is the phosphate leaving the active site.

After the initial phase of the powerstroke, there is a transition to the MgADP bound state that has been seen in EM reconstructions [6,26,27,35], which is coupled to a change in F-actin sensed by pyrene quenching. This state is followed by the final component of the lever arm swing, which releases MgADP and which is highly strain sensitive. Rebinding of MgATP terminates force generation by reopening the actin-binding cleft and allowing myosin to detach from actin.

Thus force is generated by sequential transitions through at least four discrete states on actin: (1) formation of the initial binding state (PiR state); (2) rapid transition (in the absence of load) to the state that is coupled to a large movement of the lever arm (intermediate ADP state); (3) completion of cleft closure linked to the stabilization of the C-terminal region of F-actin (formation of the strongly bound ADP state); and (4) formation of the rigor state followed by the release of ADP. These sequential transitions highlight how events at the actin interface trigger are coupled to the myosin active site to generate force by myosin motors. Different classes of myosin motors, as well as isoform variations within a class, all use this same fundamental mechanism which has been selectively tuned upon evolution for a wide range of cellular functions by altering the kinetics of these force generating transitions [36], as well as the strain-sensitivity of the transitions and the stiffness of the different states of the myosin heads.

Outstanding Questions Box.

Structural and functional studies are required to better describe the fundamentals of actomyosin force generation.

The specific interactions between myosin and actin that drive the sequential rearrangements of the actin-myosin complex must be determined to gain insights on how myosin family members are tuned for different functions and how a single mutation can impair the motor and lead to pathology.

Direct evidence is needed to demonstrate that formation of the putative phosphate release state of myosin precedes the initial large movement of the myosin lever arm.

Is the initial, rapid movement of the myosin lever arm coupled to closure of the actin-binding cleft?

Is there closure of the actin-binding cleft and movement of the myosin lever arm associated with the changes in actin that are detected by the changes in the pyrene probe on actin?

What is the impact of strain on closure of the actin-binding cleft and on the movement of the myosin lever arm? Does compliance in the myosin lever arm allow strain to decouple these two rearrangements?

Is the initial closure of the actin-binding cleft coupled to rearrangements in the myosin transducer region that are intermediate between the conformations seen in the pre-powerstroke state and the strong ADP state on actin ?

What is the mechanism that enables some myosins to act as anchors under load.

Trends Box.

A new high-resolution structure reveals rearrangements in the myosin motor that promote release of inorganic phosphate (following ATP hydrolysis).

FRET experiments reveal that, following binding to actin, the movement of the myosin lever arm (powerstroke) is extremely rapid and is faster than the rate of release of inorganic phosphate into solution.

Mutagenesis experiments suggest that phosphate release can occur prior to closure of the actin-binding cleft.

Whether the myosin lever arm is coupled to closure of the actin-binding cleft and precedes or follows the release of inorganic phosphate is controversial. Resolving this controversy is central to understanding chemo-mechanical force transduction by the myosin motor on actin.

We present a new model in which phosphate must move out of the active site prior to closure of the actin-binding cleft coupled to the lever arm swing. However, the phosphate can transiently remain bound to a second binding site at the mouth of the release tunnel, thus delaying its detection in solution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the CNRS, ANR-13-BSV8-0019-01, Ligue contre le cancer and ARC to A.H. HLS was supported by NIH grants DC009100 and HL110869. The AH team is part of Labex CelTisPhyBio 11-LBX-0038 and IDEX PSL (ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02-PSL).

A.H. was supported by grants from the CNRS, ANR-13-BSV8-0019-01, FRM-DBI20141231319. HLS was supported by NIH grants DC009100 and HL110869. The AH team is part of Labex CelTisPhyBio 11-LBX-0038 and IDEX PSL (ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02-PSL).

Glossary

- Powerstroke

the swing of the myosin lever arm on actin that generates force and movement

- Lever Arm

the extension of the myosin motor that includes the converter subdomain and the extended alpha-helix to which calmodulin (CaM) or CaM-like light chains bind. Some classes of myosins have other structural elements that can further extend this mechanical lever arm. The role of the lever arm is to amplify the sequential conformational changes within the motor domain into larger, directed movements

- Force generation

Force generation begins when myosin first binds to actin (with a lever arm primed) to initiate the powerstroke. Stereospecific binding of myosin to actin is indeed sufficient to generate force by rectification of Brownian motion

- Strong ADP state

An actin bound state of myosin that binds strongly to actin and to MgADP that is formed when the actin-binding cleft is completely closed. The Strong ADP state can be formed by adding MgADP to myosin bound to actin in the Rigor state

- Rigor state

The actin-bound state of myosin in the absence of nucleotide. It is formed at the end of the powerstroke when MgADP dissociates from the myosin

- Actin-binding cleft

A cleft that separates the upper 50 KDa (U50) and lower 50KDa (L50) subdomains of the myosin motor (Figure 2). This cleft closes upon binding to actin in order to form a strong actin-binding interface comprised of residues from both the upper and lower 50K subdomains

- Transducer

Structural elements at the heart of the motor domain comprising the 7-stranded beta-sheet and connectors that control its conformation within the myosin motor. The transducer must rearrange to coordinate binding or release of MgATP and MgADP from the nucleotide-binding pocket. The 7-stranded beta-sheet conformation is controlled in large part by the nucleotide bound in the active site of the motor. It is flat and strained when MgATP binds and it is curved and relaxed when no nucleotide is bound in the motor. An intermediate position has been seen in the state that binds both actin and MgADP with high affinity, which is a major force-generating state on actin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hartman MA, Finan D, Sivaramakrishnan S, Spudich JA. Principles of unconventional myosin function and targeting. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:133–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100809-151502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bond LM, Brandstaetter H, Sellers JR, Kendrick-Jones J, Buss F. Myosin motor proteins are involved in the final stages of the secretory pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1115–9. doi: 10.1042/BST0391115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolner S, Bement WM. Unconventional myosins acting unconventionally. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross JL, Ali MY, Warshaw DM. Cargo transport: molecular motors navigate a complex cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llinas P, et al. How actin initiates the motor activity of myosin. Dev Cell. 2015;33:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wulf SF, et al. Force-producing ADP state of myosin bound to actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1844–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516598113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von der Ecken J, Heissler SM, Pathan-Chhatbar S, Manstein DJ, Raunser S. Cryo-EM structure of a human cytoplasmic actomyosin complex at near-atomic resolution. Nature. 2016;534:724–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muretta JM, Rohde JA, Johnsrud DO, Cornea S, Thomas DD. Direct real-time detection of the structural and biochemical events in the myosin power stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:14272–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514859112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi DV, et al. Direct measurements of the coordination of lever arm swing and the catalytic cycle in myosin V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(47):14593–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517566112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muretta JM, Petersen KJ, Thomas DD. Direct real-time detection of the actin-activated power stroke within the myosin catalytic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7211–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222257110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweeney HL, Houdusse A. Structural and functional insights into the Myosin motor mechanism. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:539–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayment I, et al. Three-dimensional structure of myosin subfragment-1: a molecular motor. Science. 1993;261:50–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yount RG, Lawson D, Rayment I. Is myosin a “back door” enzyme? Biophys J. 1995;68:44S–47S. discussion 47S–49S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson JD, Pate E, Rayment I, Yount RG. Molecular dynamics analysis of structural factors influencing back door pi release in myosin. Biophys J. 2004;86:3794–803. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.037390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De La Cruz EM, Ostap EM, Sweeney HL. Kinetic mechanism and regulation of myosin VI. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32373–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik FI, et al. Cardiac myosin activation: a potential therapeutic approach for systolic heart failure. Science. 2011;331:1439–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1200113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, White HD, Belknap B, Winkelmann DA, Forgacs E. Omecamtiv Mecarbil modulates the kinetic and motile properties of porcine β-cardiac myosin. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1963–75. doi: 10.1021/bi5015166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohde JA, Thomas DD, Muretta JM. Structural and biochemical kinetics of cardiac myosin and its perturbation by a known heart failure drug investigated with transient time-resolved FRET. Biophysical J. 2016;110(3):296a. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caremani M, Dantzig J, Goldman YE, Lombardi V, Linari M. Effect of inorganic phosphate on the force and number of myosin cross-bridges during the isometric contraction of permeabilized muscle fibers from rabbit psoas. Biophys J. 2008;95:5798–808. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takagi Y, Homsher EE, Goldman YE, Shuman H. Force generation in single conventional actomyosin complexes under high dynamic load. Biophys J. 2006;90:1295–307. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellers JR, Veigel C. Direct observation of the myosin-Va power stroke and its reversal. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:590–5. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huxley AF. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ait-Haddou R, Herzog W. Brownian ratchet models of molecular motors. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;38:191–213. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:2:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature. 1971;233:533–8. doi: 10.1038/233533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caremani M, et al. Force and number of myosin motors during muscle shortening and the coupling with the release of the ATP hydrolysis products. J Physiol. 2015;593:3313–32. doi: 10.1113/JP270265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittaker M, et al. A 35-A movement of smooth muscle myosin on ADP release. Nature. 1995;378:748–51. doi: 10.1038/378748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jontes JD, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Milligan RA. A 32 degree tail swing in brush border myosin I on ADP release. Nature. 1995;378:751–3. doi: 10.1038/378751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veigel C, Wang F, Bartoo ML, Sellers JR, Molloy JE. The gated gait of the processive molecular motor, myosin V. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:59–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coureux PD, et al. A structural state of the myosin V motor without bound nucleotide. Nature. 2003;425:419–23. doi: 10.1038/nature01927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reubold TF, et al. A structural model for actin-induced nucleotide release in myosin. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:826–30. doi: 10.1038/nsb987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenfeld SS, Houdusse A, Sweeney HL. Magnesium regulates ADP dissociation from myosin V. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6072–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujita-Becker S, et al. Changes in Mg2+ ion concentration and heavy chain phosphorylation regulate the motor activity of a class I myosin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6064–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coureux PD, Sweeney HL, Houdusse A. Three myosin V structures delineate essential features of chemo-mechanical transduction. EMBO J. 2004;23:4527–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Várkuti BH, Yang Z, Kintses B, Erdélyi P, Bárdos-Nagy I, Kovács AL, Hári P, Kellermayer M, Vellai T, Málnási-Csizmadia A. A novel actin binding site of myosin required for effective muscle contraction. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:299–306. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volkmann N, et al. The structural basis of myosin V processive movement as revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Mol Cell. 2005;19:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloemink MJ, Geeves MA. Shaking the myosin family tree: biochemical kinetics defines four types of myosin motor. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:961–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]