Abstract

Background

With tetanus being a leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in low and middle income countries, ensuring that pregnant women have geographic access to tetanus toxoid (TT) immunization can be important. However, immunization locations in many systems may not be placed to optimize access across the population. Issues of access must be addressed for vaccines such as TT to reach their full potential.

Methods

To assess how TT immunization locations meet population demand in Mozambique, our team developed and utilized SIGMA (Strategic Integrated Geo-temporal Mapping Application) to quantify how many pregnant women are reachable by existing TT immunization locations, how many cannot access these locations, and the potential costs and disease burden of not covering geographically harder-to-reach populations. Sensitivity analyses covered a range of catchment area sizes to include realistic travel distances and to determine the area some locations would need to cover in order for the existing system to reach at least 99% of the target population.

Results

For 99% of the population to reach health centers, people would be required to travel up to 35km. Limiting this distance to 15km would result in 5,450 (3,033–7,108) annual cases of neonatal tetanus that could be prevented by TT, 144,240 (79,878–192,866) DALYs, and $110,691,979 ($56,180,326–$159,516,629) in treatment costs and productivity losses. A catchment area radius of 5km would lead to 17,841 (9,929–23,271) annual cases of neonatal tetanus that could be prevented by TT, resulting in 472,234 (261,517–631,432) DALYs and $362,399,320 ($183,931,229–$522,248,480) in treatment costs and productivity losses.

Conclusion

TT immunization locations are not geographically accessible by a significant proportion of pregnant women, resulting in substantial healthcare and productivity costs that could potentially be averted by adding or reconfiguring TT immunization locations. The resulting costs savings of covering these harder to reach populations could help pay for establishing additional immunization locations.

Keywords: immunization, geospatial analysis, tetanus, access

INTRODUCTION

With tetanus being a leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in low and middle income countries, ensuring that pregnant women have geographic access to tetanus toxoid (TT) immunization can be important. Tetanus results from toxins produced by Clostridium tetani that block neurotransmitter release and leads to generalized muscle spasm, respiratory compromise, and autonomic dysfunction.[1] The TT vaccine is a routine part of many countries’ World Health Organization (WHO) expanded program on immunization (EPI) regimens. Studies have shown the TT vaccine to be highly efficacious (80–100%) in preventing neonatal tetanus (NNT).[2] However, the continuing occurrence of NNT – which is estimated to have caused 61,000 deaths in 2011[3] – suggests that many pregnant women are not receiving the TT vaccine. Indeed, only 64% of pregnant women are estimated to have received at least two doses of TT in 2014.[4] As previous work has shown, distance to the closest immunization location can be an impediment to a person getting immunized.[5] However, immunization locations in many systems may not be placed in a planned manner to optimize access across the population. Instead, decision makers may prioritize other factors, such as political considerations.[6] Issues of access must be addressed in order for vaccines in the current routine immunization schedule to reach their full potential, let alone new and upcoming vaccines.

To determine how well the TT immunization locations meet the population demand in Mozambique, our team developed and utilized SIGMA (Strategic Integrated Geo-temporal Mapping Application) to quantify how many people in the relevant target population are reachable by existing TT immunization locations in Mozambique, how many cannot access these locations, and the potential costs and disease burden of not reaching these geographically harder-to-reach populations.

METHODS

Mozambique Population and Immunization

Mozambique is a low-income country in southern Africa with a population of 25,727,911.[7] Based on data from the Ministry of Health (MOH), the EPI in Mozambique administers vaccines to the population at 1,377 health centers located throughout the country. The EPI schedule currently includes TT for pregnant women, who on average comprise 5% of the population, to prevent neonatal tetanus.

SIGMA

For this study, we developed SIGMA for Immunization, a geospatial information system (GIS) to estimate the population that may be reachable by specified immunization locations. SIGMA is written in the Python and Javascript programming languages, using the Django web application framework[8] and Leaflet interactive mapping library[9], and includes points-of-interest (POI) data from OpenStreetMap[10] as well as population density data from the Global Rural-Urban Mapping Project (GRUMP)[11]. A SIGMA-generated model allows one to place immunization locations on a map and draw a catchment area around each location. The model overlays these catchment layers onto geospatially explicit population data that incorporates the immunization target population based on relevant demographic statistics (e.g. crude birth rate to estimate newborn population and different age groups of the population over time). SIGMA can be used to characterize the population served by these catchment areas, and the populations not served by any catchment area. Using a combination of disease risk, vaccine efficacy, and cost and burden of each disease case, the reachable and unreachable populations can be translated into disease cases, costs (e.g. treatment and productivity losses), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

Data Sources

We searched four major electronic databases (the United States National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health Medical (PubMed)[12], WHO Global Health Observatory Data Repository[11], Scopus[13], and EconLit[14]) to locate peer-reviewed studies and grey literature on the costs and health effects of tetanus between 2005 and 2014. Our primary focus was the disease risk, vaccine efficacy, and costs and burden per case of neonatal tetanus in Mozambique; however, due to the limited number of papers specific to this country, we expanded our search to include other countries. The search, performed in 2015, used variations of the following keywords: “tetanus,” “epidemiology,” AND “economics.” Relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and a full listing of all types of impact evaluations were used in the search. Additional manual bibliographic searches from relevant review papers revealed additional articles and grey literature. We limited our search to English and French studies presenting tetanus impact data conducted between 2005 and 2014 in Mozambique and other African countries.

We based our estimates of disease risk and burden on baseline, high, and low values found in the literature. We used 100% (80%–100%) for TT vaccine efficacy[2], with unprotected individuals developing neonatal tetanus at a rate of 23 per 1,000 live births[15]. Each case of neonatal tetanus incurs $3,410 ($1,705–$5,114) in treatment costs in 2015 USD[16] and $16,903 ($16,820–$17,327) in productivity losses (based on a $639 GNI per capita[17]). Productivity losses represent the net present value of all productivity lost over the lifetime of the patient due to illness, disability, and loss in life years. Each case also incurs 26.5 (26.3–27.1) DALYs[18], based on disability weights of 0.640 per acute episode of tetanus, 0.388 for motor deficits, and 0.469 for mental retardation in children 0–4 years of age[19, 20]. To estimate treatment costs, we converted costs from Brazil reported in 2010 USD to Mozambican Meticais (MZN), accounting for the purchase power parity (PPP). We used the monetary conversion rates from USD to Brazilian Real (BRL) in 2010 (year of reported costs), the PPP conversion factor for BRL into PPP International dollar ($Int) in 2010, and the PPP conversion factor for Mozambican Metical (MZN) into PPP $Int in 2010. We used these indicators in Equation 1 to derive the Mozambican cost equivalent.

| (1) |

Immunization Location Catchment Area Scenarios

Each scenario tested a catchment area radius for health centers (i.e. the greatest distance pregnant women may travel to obtain TT) to determine the percentage of the population reachable by these locations. As data on the actual catchments are lacking, sensitivity analyses covered a range of catchment area sizes to include realistic travel distances and to determine the area some locations would need to cover in order for the existing system to reach at least 99% of the target population.

For each scenario, we quantified the number of pregnant women who would fall outside the catchment area of any health center. We estimated the annual number of vaccine-preventable cases of neonatal tetanus each scenario would incur among unreachable populations (Equation 2), as well as the resulting DALYs, healthcare costs, and societal costs in the form of productivity losses. Costs are reported in 2015 USD assuming a 3% discount rate.

| (2) |

RESULTS

Population Reachable and Not Reachable by TT Immunization Locations

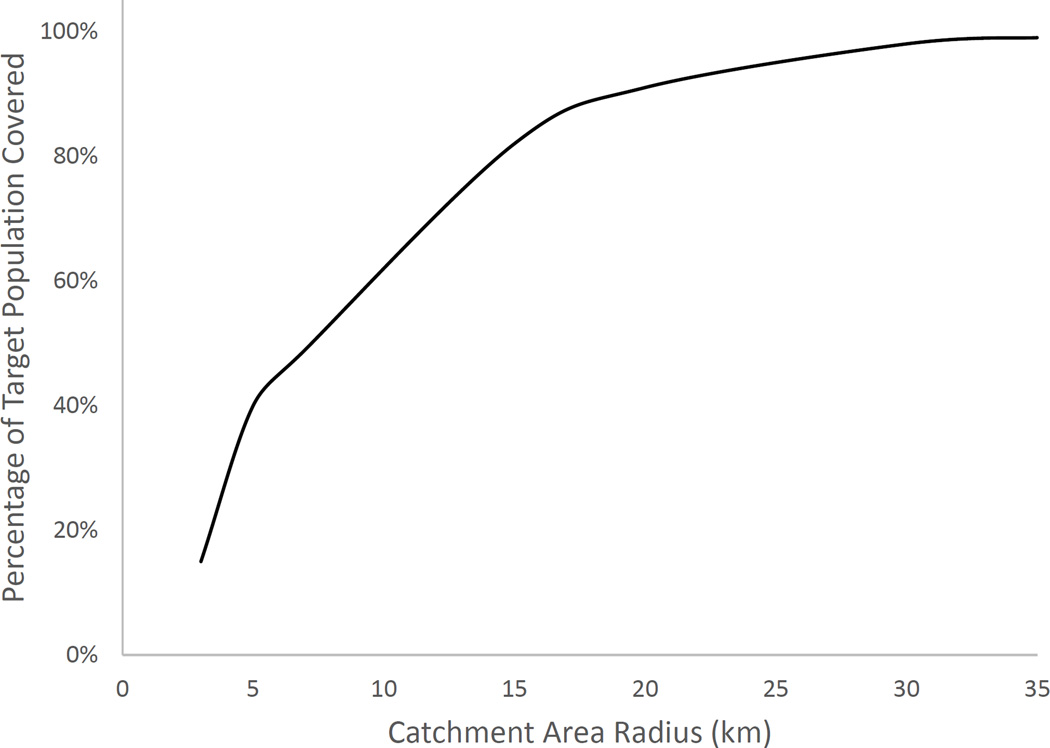

Figure 1 shows the relationship between catchment radius and target population covered. The population covered increases at an accelerating rate until it peaks at 17% additional population coverage for each added kilometer in catchment area radius. Beyond a radius of 4km, each subsequent gain in population coverage requires a larger increase in catchment area radius. A health center catchment area radius of 5km would cover only 40% of the population (Table 1), meaning 775,715 pregnant women could not be reached by health centers for tetanus immunization. A radius of 15km would cover 82%, and a catchment area radius of 30km covers 98% of the population. For 99% of the population to reach health centers, people would be required to travel up to 35km. The rapid rise in coverage at lower catchment radii suggests that urban or densely populated areas are saturating, and capturing people in rural or less densely populated areas requires much wider reach by the health centers.

Figure 1. Percentage of TT target population covered versus catchment area size in Mozambique.

Table 1.

Neonatal tetanus cases and associated costs and DALYs among those not reachable by current TT immunization locations.

| Catchment area radius (km) |

Target population not reachable |

Annual vaccine- preventable tetanus cases among those not reachable |

Annual vaccine-preventable tetanus-associated DALYsa among those not reachable |

Annual vaccine-preventable tetanus associated costs (2015 USD, thousands) among those not reachable |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Costs | Productivity Losses | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | Low | High | Baseline | Low | High | Baseline | Low | High | Baseline | Low | High | ||

| 3 | 1,091,709 (85%) |

25,109 | 13,974 | 32,751 | 664,603 | 368,048 | 888,651 | $85,610 | $23,822 | $167,498 | $424,415 | $235,035 | $567,492 |

| 5 | 775,715 (60%) |

17,841 | 9,929 | 23,271 | 472,234 | 261,517 | 631,432 | $60,831 | $16,927 | $119,016 | $301,569 | $167,004 | $403,232 |

| 7 | 655,576 (51%) |

15,078 | 8,391 | 19,667 | 399,097 | 221,014 | 533,639 | $51,409 | $14,305 | $100,584 | $254,863 | $141,140 | $340,782 |

| 15 | 236,936 (18%) |

5,450 | 3,033 | 7,108 | 144,240 | 79,878 | 192,866 | $18,580 | $5,170 | $36,353 | $92,112 | $51,010 | $123,164 |

| 20 | 110,006 (9%) |

2,530 | 1,408 | 3,300 | 66,969 | 37,086 | 89,545 | $8,627 | $2,400 | $16,878 | $42,766 | $23,683 | $57,183 |

| 30 | 26,573 (2%) |

611 | 340 | 797 | 16,177 | 8,958 | 21,630 | $2,084 | $580 | $4,077 | $10,330 | $5,721 | $13,813 |

| 35 | 12,899 (1%) |

297 | 165 | 387 | 7,853 | 4,349 | 10,500 | $1,012 | $281 | $1,979 | $5,015 | $2,777 | $6,705 |

DALYs = disability-adjusted life years

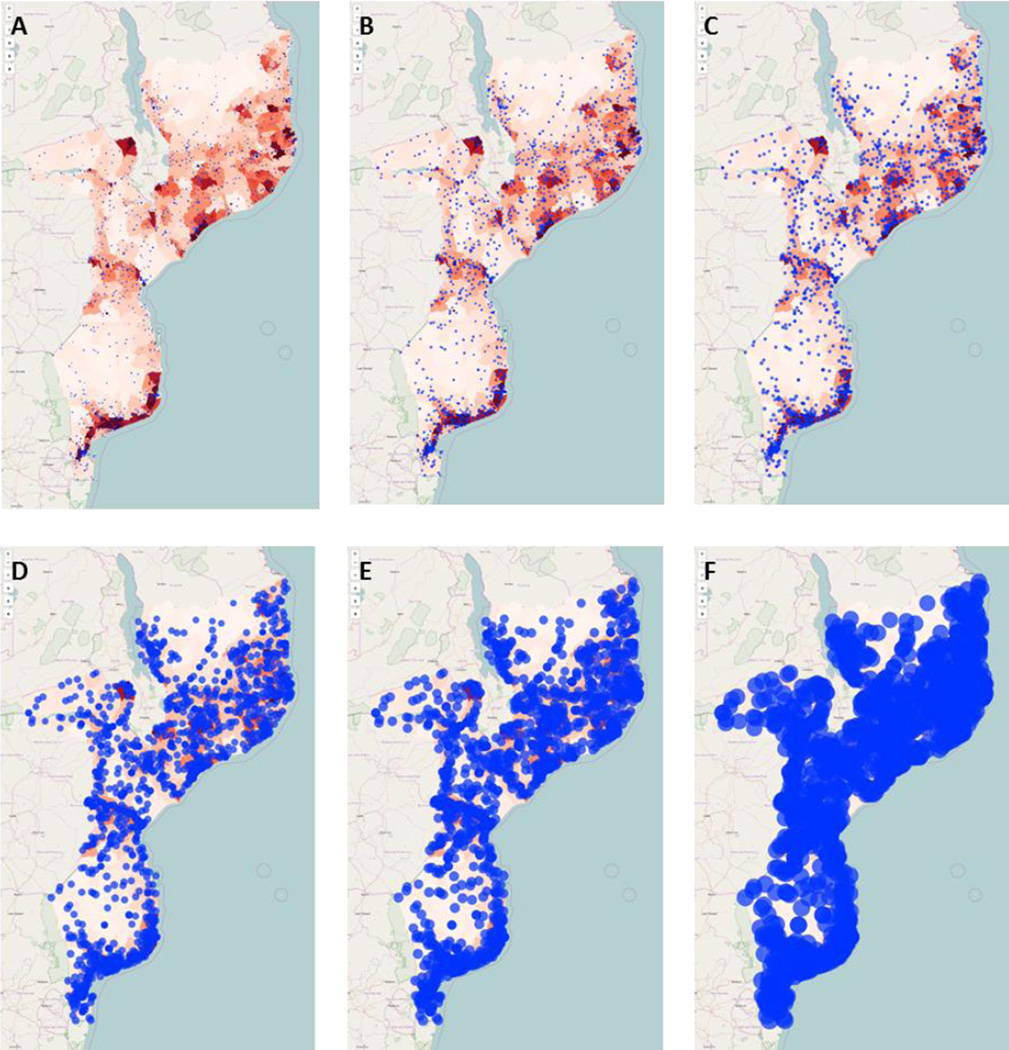

Figure 2 displays SIGMA geographic visualizations of six scenarios with progressively larger catchment area radii. In all scenarios, rural populations are overrepresented among those unreachable by immunization locations. Even at a catchment area radius of 35km (Figure 2F), visible gaps in coverage exist in Gaza, Niassa, and Cabo Delgado provinces.

Figure 2. SIGMA visualizations of TT immunization locations and their catchment areas.

Each health center and its catchment is plotted as a blue circle onto a population density map of Mozambique, in which higher intensity red indicates greater density of the TT target population. Any population not covered by a blue circle is considered to be unreachable by immunization locations. Six example scenarios from sensitivity analyses are shown, with catchment area radii of (A) 3km, (B) 5km, (C) 7km, (D) 15km, (E) 20km, and (F) 35km.

Economic Impact of Covering the Currently Hard to Reach Populations

As the population covered increases at a diminishing rate after the catchment area radius surpasses 4km, vaccine-preventable disease cases, costs, and DALYs decrease with similarly diminishing returns (Table 1). A catchment area radius of 5km would lead to 17,841 (9,929–23,271) annual vaccine-preventable cases of neonatal tetanus, resulting in 472,234 (261,517–631,432) DALYs and $362,399,320 ($183,931,229–$522,248,480) in treatment costs and productivity losses. A 15km catchment area radius would reduce the annual vaccine-preventable cases to 5,450 (3,033–7,108) to incur 144,240 (79,878–192,866) DALYs and $110,691,979 ($56,180,326–$159,516,629) in costs. Reaching 99% of the population would lead to 297 (165–387) vaccine-preventable cases annually, which translates to 7,853 (4,349–10,500) DALYs and $6,026,181 ($3,058,513–$8,684,243) in costs.

Because not everyone who is geographically reachable may be compliant with the recommended immunization schedule, a number of vaccine-preventable cases, costs, and DALYs may occur within the catchment areas of health centers. Even in the scenario where each health center is able to cover a 35km radius, meaning 99% of all pregnant women are reachable, a 10% TT refusal rate would raise the annual vaccine-preventable cases to 3,226 (1,795–4,207), leading to 85,380 (47,282–114,162) DALYs and $65,521,552 ($33,254,642–$94,422,172) in treatment costs and productivity losses.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that a significant proportion of pregnant women in Mozambique may not have ready geographic access to current TT immunization locations, potentially resulting in substantial costs to society via healthcare costs and productivity losses. Studies have shown the value of TT immunization.[2] However, when pregnant women cannot even reach immunization locations, other approaches to increasing TT coverage – such as advocacy and communications, training, new administration technologies, and decreased vaccine prices – would have little effect.

It is unclear how far pregnant women may be willing to travel for TT immunization. This would depend on the transportation available, the terrain, and each individual’s family and social situation. The distance at which TT immunization becomes unmanageable for pregnant women varies by region, but studies suggest that the location of vaccination services relative to an individual’s household is a significant factor in the uptake of TT vaccine. A study by Perry, et al. conducted in Bangladesh found that the distance from a woman’s household to the nearest immunization center significantly affected the odds of seeking a second dose of TT, with a household distance of greater than 4km reducing coverage by a factor of 0.47.[21] Studies conducted in Jordan and Ghana also found a significant association between the accessibility of health centers and low TT coverage amongst pregnant women.[22, 23] Available studies suggest that traveling 35km will be unrealistic for most pregnant women and that in most cases pregnant women will not travel further than 11km.[24]

It appears that in Mozambique a large percentage of geographically unreachable populations are located in rural areas which are much less densely populated than the urban centers. According to a 2003 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) report, 81% of children living in urban areas in Mozambique were fully immunized as compared to only 56% of their rural counterparts.[25] These disparities in coverage levels may be even more pronounced in individual districts, with children in rural Maputo province achieving full immunization status at coverage levels approximately 40% lower (49.2%) than that of their urban counterparts Maputo city (90.2%).[26]

A number of factors contribute to the reduced ability of individuals in rural areas to access immunization services. As families living in rural areas tend to have lower household incomes, even the cost of lost wages and transportation to a health center can prove to be prohibitive. Additionally, health services staff are not distributed evenly throughout the country. The existing health services infrastructure in many rural districts often lacks the resources required to reach remote communities, while low population density produces large catchment areas in many districts.[27] In Mozambique, tetanus immunization largely occurs at fixed vaccination locations such as health centers or antenatal clinics whose placement is typically based on political boundaries or population density. It is estimated, however, that 50% of the population is not currently served by the existing health network sites.[26] Many districts have communities that are difficult to access with existing health services infrastructure, making outreach essential to improving coverage at the district level. Despite the need for outreach, a lack of capacity and resources often hinders the ability to implement these activities in remote communities, as the necessary transportation resources are available at only 30% of fixed health facilities.[26] Other potential solutions that do not involve adding immunization sites include providing transportation to bring women to existing health centers or reimbursing them for their travel expenses, as well as providing additional compensation for their time. Such interventions may cost less than outreach immunization activities and may provide the opportunity for pregnant women to also receive other services provided at health centers that are not available at outreach sessions.

Of course, geographical access does not guarantee that pregnant women will receive tetanus immunization. Even for pregnant women living in close proximity to a health facility, low education levels and a lack of awareness regarding the need for immunization can lead to a reluctance to seek TT. Negative attitudes and beliefs regarding vaccination, which can be cultural or religion-based, also reduce uptake. This may particularly be the case for women who feel religious or household pressure to not get the vaccine. Additionally, socioeconomic status has been found to be a deterrent to vaccination.[28] Women of low socioeconomic status may not be able to leave their household or work duties for the time required to travel to a health facility or they may simply not be able to afford immunization. Even if the vaccine is provided free of charge, the indirect costs of transportation and time being away from work may be too high.[29] Previous interactions with health facility workers can also affect the decision of pregnant women to seek vaccination based on misinformation or a negative experience. Given these challenges, immunization locations should be configured to ensure geographic access does not pose yet another barrier to immunization.

LIMITATIONS

Fundamentally, models provide simplified portrayals of reality and cannot embody all factors that affect immunization coverage and impact. This analysis uses the population density of Mozambique from 2000 (from currently available data) extrapolated to estimates of the current number of pregnant women, which should provide a reasonable estimate for this analysis but may miss some details that would be elucidated by collecting more recent data. Additionally, the determination of catchment areas is solely based on straight-line distance from a location, which may not capture factors such as travel times and geographic variation. Disease cost and impact data for Mozambique were sparse and, in some cases, supplemented with data from other countries. While we report a range for each result, it is possible that more localized input values may lead to different effect sizes.

CONCLUSION

Our study shows that TT immunization locations, as currently configured, are not geographically accessible by a significant proportion of pregnant women, which is resulting in substantial healthcare and productivity costs to society that could potentially be averted by adding or reconfiguring TT immunization locations. The resulting costs savings of covering these harder to reach populations could help pay for establishing additional immunization locations.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Tetanus is a leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in LMICs

Ensuring geographic access to tetanus toxoid (TT) immunization is vital

We used SIGMA to quantify geographic access to TT and disease impact in Mozambique

People must travel up to 35km for 99% of the population to reach health centers

TT can prevent significant disease burden and costs if geographic access is improved

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID) and Pfizer via the SIGMA grant and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) via grant R01HS023317, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) and the Global Obesity Prevention Center (GOPC) via grant U54HD070725, NICHD via grant U01 HD086861, the National Institute for General Medical Science (NIGMS) via the MIDAS 5U24GM110707 grant, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) via contract 200-2015-M-63169. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 13th. Washington D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Tetanus vaccine: WHO position paper. Weekly epidemiological record. 2006;81:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Neonatal tetanus. Available at: http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/active/neonatal_tetanus/en/

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Global and regional immunization profile. 2015 Available at: http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/gs_gloprofile.pdf?ua=1.

- 5.Lee BY, Mehrotra A, Burns RM, Harris KM. Alternative vaccination locations: who uses them and can they increase flu vaccination rates? Vaccine. 2009;27:4252–4256. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hipgrave DB, Alderman KB, Anderson I, Soto EJ. Health sector priority setting at meso-level in lower and middle income countries: lessons learned, available options and suggested steps. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Instituto Nacional de Estatística Moçambique. Available at: http://www.ine.gov.mz/

- 8.Django. Version 1.8.7. Available at: https://www.djangoproject.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leaflet. Version 0.7.7. Available at: http://leafletjs.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.OpenStreetMap. Available at: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization (WHO) PQS catalogue: Prequalified devices and equipment. Available at: http://apps.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/pqs_catalogue/categorylist.aspx.

- 12.United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institutes of Health (NIH) PubMed. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

- 13.Elsevier. Scopus. Available at: http://www.scopus.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Economic Association (AEA) EconLit. Available at: https://www.aeaweb.org/econlit/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quddus A, Luby S, Rahbar M, Pervaiz Y. Neonatal tetanus: mortality rate and risk factors in Loralai District, Pakistan. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:648–653. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda-Filho DB, Ximenes RA, Siqueira-Filha NT, Santos AC. Incremental costs of treating tetanus with intrathecal antitetanus immunoglobulin. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:555–563. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Bank. GNI per capita, Atlas method. 2015 Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths UK, Wolfson LJ, Quddus A, Younus M, Hafiz RA. Incremental cost-effectiveness of supplementary immunization activities to prevent neonatal tetanus in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:643–651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray CJL, Lopez L, editors. The global burden of disease. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry H, Weierbach R, Hossain I, Islam R. Tetanus toxoid immunization coverage among women in zone 3 of Dhaka city: the challenge of reaching all women of reproductive age in urban Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:449–457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbas AA, Walker GJ. Determinants of the utilization of maternal and child health services in Jordan. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15:404–407. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anokye M, Mensah J, Frimpong F, Aboagye E, Acheampong N. Immunization coverage of pregnant women with tetanus toxoid vaccine in Dormaa East District-Brong Adaro Region, Ghana. Mathematical Theory and Modeling. 2014;4:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naeem M, Khan MZ, Abbas SH, Adil M, Khan A, Naz SM, et al. Coverage and factors associated with tetanus toxoid vaccination among married women of reproductive age: a cross sectional study in Peshawar. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22:136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, Ministerio da Saude, ORC Macro. Mocambique Inquerito Demografico e de Saude. Calverton, MD: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mozambique Ministry of Health. Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan (cMYP) 2012–2016. 2011 Available at: http://www.gavi.org/Country/Mozambique/Documents/CMYPs/Comprehensive-multi-year-plan-for-2012-2016/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Geneva: WHO; 2015. Country-Programmes: Expanded program of immunization: Mozambique. Available at: http://www.afro.who.int/en/mozambique/country-programmes/mother-and-child-health/expanded-program-of-immunization.html. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia E. Factors associated with suboptimal compliance to vaccinations in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1719–1741. doi: 10.1185/03007990802085692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, Sandhu P, Bo A, Banerjee K. Reasons related to nonvaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999–2009. Vaccine. 2011;29:8215–8221. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]