Abstract

In a select group of patients with proximal anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, primary repair can be a useful technique. Preservation of the native ACL may be advantageous for proprioceptive function and is thought to restore normal knee joint kinematics. The procedure is a less morbid and more conservative surgical approach to restore knee stability. Primary repair is preferably performed in the acute setting because of better healing capacity and tissue quality. We present the surgical technique of arthroscopic primary ACL repair with suture anchors in patients with proximal tears and excellent tissue quality.

Historically, poor midterm outcomes of open primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) were described in the literature. This led to the general opinion that primary repair of ACL tears deteriorated over time or were technically too demanding.1 The results of an oft-quoted study by Feagin and Curl led to the generalized preference of ACL reconstruction over ACL repair.1, 2 The authors reported their results of acute repair of isolated ACL tears in 32 military cadets at 5-year follow-up. They reported that 17 patients (53%) had experienced a rerupture, whereas 30 patients (94%) reported instability. This was a significant deterioration of clinical results from their 2-year results, and these findings were echoed by others.3 In retrospect, several major limitations could be noted in most of the historic studies on open ACL repair: primary repairs were attempted on all types of ACL tears (i.e., proximal, midsubstance, and distal), many patients had significant concomitant ligamentous injuries, an open approach was used that was very morbid to the patient, and postoperative management consisted of cast immobilization for 6 weeks that led to significant motion and patellofemoral issues.2, 3

The type of tear is, however, of critical importance to the potential success of primary ACL repair. In their landmark paper, Sherman et al.1 reported on open, primary ACL repair in 50 patients and uniquely performed extensive subgroup analysis. The authors found that certain subgroups were noted to have better results, including those with proximal (type I) ACL tears and good to excellent tissue quality. Despite these findings in 1991, and other good results that were reported in repairing proximal tears,4 the focus of the surgeons was diverted to ACL reconstruction. The technique of open primary ACL repair, and any attempt at primarily repairing ACL tears, for that matter, was abandoned.

Expanding on the findings of Sherman et al. by focusing on appropriate injury subgroups, while minimizing the morbidity of the procedure by using arthroscopic techniques, we describe the surgical technique of arthroscopic, suture anchor primary ACL repair in patients with proximal tears and excellent tissue quality. This technique is in the clinic of the senior author (G.S.D.) preferred over ACL reconstruction in patients with proximal ACL tears. The goal of arthroscopic primary repair is preservation of the native ACL with its proprioceptive function and kinematics, and the clinical results using this technique have been rather encouraging.5

Surgical Technique

General Preparation

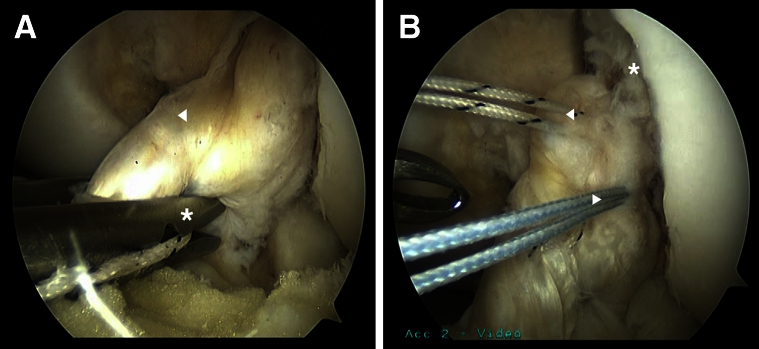

The patient is placed in the supine position and the operative leg is prepped and draped as for knee arthroscopy (Video 1, Table 1). Equipment and implants from both the standard knee arthroscopy set and the standard shoulder arthroscopy set are used. Anteromedial and anterolateral portals are created and a general inspection of the knee joint is performed. A malleable Passport cannula (Arthrex, Naples, FL) is placed in the anteromedial portal to facilitate suture passage, management, and repair of the ACL. General assessment is performed for the type of ligamentous tear, ligamentous tissue quality, and the possibility of a repair (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Pearls and Pitfalls of Arthroscopic Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair

| Surgical Pearls and Pitfalls |

|---|

| Use magnetic resonance imaging to identify proximal tears. |

| Evaluate tissue quality for eligibility of primary repair. |

| Use a cannula in the anteromedial portal to facilitate suture management. |

| Try to get first suture pass as distal as possible. |

| Use self-retrieving suture passer to pass sutures. |

| Avoid transecting previously placed sutures by monitoring resistance. |

| Consider accessory portal to park sutures and avoid suture damage. |

| Use a low accessory inferomedial portal to optimize the angle for suture placement. |

| Flex knee at 90° for anteromedial bundle anchor placement and 110° for posterolateral bundle anchor placement to avoid posterior perforation. |

Fig 1.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. A proximal tear (asterisk) is visible, but the exact location of the tear needs to be assessed by a probe. Excellent tissue quality of the anteromedial (left arrowhead) and posterolateral bundle (right arrowhead) is seen. (B) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. A proximal type I tear (arrowhead) with good tissue quality is shown after a probe (asterisk) is used to remove the remnant from the femoral wall.

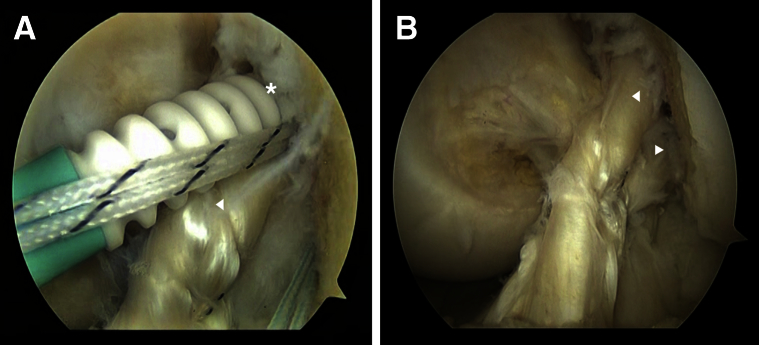

Suturing of ACL Bundles

Once the ligament is deemed suitable for repair (Table 2), the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of ACL are identified. First, the sutures are passed through the anteromedial bundle using the Scorpion Suture Passer (Arthrex) with a No. 2 TigerWire suture (Arthrex) (Fig 2A). Suturing is started at the intact distal end of the anteromedial bundle and is advanced in an alternating, interlocking Bunnell-type pattern toward the avulsed proximal end. In general, 3 to 4 passes can be made before the final pass exits the avulsed end of the ligament toward the femur. The same process is then repeated for the posterolateral bundle of the ACL remnant with a No. 2 FiberWire suture (Arthrex) (Fig 2B). Great care should be taken to not transect the previously passed suture. When greater resistance is experienced, the suture-passing device should be repositioned.

Table 2.

Indications and Contraindications of Arthroscopic Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Proximal tears | Midsubstance tears |

| Good to excellent tissue quality | Poor tissue quality |

| All age categories | Chronic tears with tissue reabsorption |

| All activity levels | |

| Multiligamentous injured knees | |

| Pediatric patients |

Fig 2.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. A suture passer (asterisk) is used to pass a No. 2 TigerWire suture through the anteromedial bundle (arrowhead). The suture is passed in an alternating, interlocking Bunnell-type pattern. (B) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. Two different sutures have been passed through both the anteromedial (left arrowhead) and posterolateral bundle (right arrowhead). The proximal tear is visible (asterisk).

After passing the sutures through both bundles, the sutures are docked using an accessory portal, just above the medial portal. Retracting the ligament away ensures good visibility of the femoral footprint. Using a shaver or burr, some bleeding of the notch wall and femoral footprint is induced to encourage healing. Then, with the knee in flexion, an accessory inferomedial portal is created under direct visualization, using a spinal needle for localization, followed by incision and dilation with a blunt trocar. Care is taken to check the trajectory such that access to the femoral footprint is possible.

Suture Fixation

With the knee flexed at 90°, a 4.5 mm × 20 mm hole is drilled, punched, or tapped, depending on bone density, into the origin of the anteromedial bundle within the femoral footprint. The TigerWire sutures are then retrieved through the accessory portal and passed through the eyelet of a 4.75-mm Vented, BioComposite SwiveLock suture anchor (Arthrex). By flexing the knee, the placement of the anchors can be visualized. At 90° of flexion, the first suture anchor is deployed into the femur toward the anteromedial origin while tensioning the ACL remnant to the wall with a visual gap of less than 1 mm (Fig 3A). This procedure is then repeated for the posterolateral bundle with the FiberWire stitches with the knee at 110° to 115° of flexion. This ensures an optimal angle of approach to the femoral notch wall, and avoids perforation of the posterior condyle with the anchor. The hole is made, and the anchor deployed into the origin of the posterolateral bundle within the femoral footprint.

Fig 3.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. After creating a 4.5 mm × 20 mm hole in the anteromedial bundle origin of the femoral wall, the suture anchor of the anteromedial bundle is deployed into the femur toward the hole (asterisk), whereas the anteromedial bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) remnant (arrowhead) is tensioned to the wall. (B) Arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. A completed primary ACL repair is seen after both the anteromedial (left arrowhead) and posterolateral bundle (right arrowhead) are deployed into the femoral wall at their anatomic origin.

Once the anchors are fully deployed and flush with the femoral footprint, the handle is removed, the core stitches are unloaded, and the free ends of the repair sutures are cut with an Open-Ended Suture Cutter (Arthrex) so that they are flush with the wall. After deploying both anchors the repair is complete (Fig 3B). The ACL remnant is tested for tension and stiffness using a probe. Finally, range of motion (ROM) is assessed and anatomic positioning should be visualized without graft impingement. Intraoperative Lachman examination should reveal minimal anteroposterior translation with a firm endpoint.

Rehabilitation Protocol

The main goals of rehabilitation are to control edema and to obtain early ROM. A brace is worn for the first 4 weeks along with weight bearing as tolerated. Initially, the brace is locked in extension until volitional quadriceps control returned and then the brace unlocked for ambulation. ROM exercises are initiated in the first few days after surgery in a controlled fashion, but formal physical therapy does not absolutely need to commence until after 1 month. Four to 6 weeks postoperatively, the patient is advanced to gentle strengthening and the standard ACL rehabilitation protocol. Early recovery tends to be dramatically faster than with conventional reconstruction due to the minimally morbid nature of the procedure.

Discussion

Studies performed in the 1970s and 1980s reported mixed functional outcomes and high failure rates of open primary ACL repair.1, 2 These studies, however, lacked appropriate patient selection, and the results of these studies should therefore be evaluated with caution. The aforementioned study of Sherman et al.1 showed that patient selection (e.g., proximal tears with good to excellent tissue quality) regarding primary ACL repair is critical.

With this in mind, a second look at the historic literature helps one to understand why some studies reported superior results over others. In 1993, Genelin et al.4 reported their results of mini-open, primary repair of 49 fresh proximal ACL tears. At midterm follow-up, they reported that 81% had a KT-1000 laxity less than 3 mm, a negative pivot shift, and a Lysholm score greater than 85. Furthermore, 84% of the patients were satisfied with the procedure. These promising results were noted despite the fact that the procedure was still performed via a mini-open arthrotomy, and the patients were cast immobilized for 6 weeks postoperatively. They stated,

in comparison to results published by others, our results seem to be significantly better, the reason for which is probably that our investigation was entirely restricted to proximal avulsion injuries of the ACL. Nevertheless we believe that, even with the same operational technique, the results can be improved still further by early postoperative treatment with a continuous passive motion machine, combined with a brace providing limited knee joint motion.

More recently, DiFelice et al.5 reported a case series of proximal ACL repairs in which they used a minimally invasive, arthroscopic suture anchor technique and encouraged early ROM. In light of the experience of Genelin et al.,4 with these modern advances, it is not surprising that they reported excellent results at 3.5-year average follow-up. The authors reported only 1 failure of 11 patients (9%), a mean Lysholm score of 93.2, a mean modified Cincinnati score of 91.5, a mean subjective International Knee Documentation Committee score of 86.4, and objective International Knee Documentation Committee A-scores in 8 patients, B-score in 1 patient, and C-score in 1 patient. In addition, KT-1000 results were available on 8 patients, with 7 of 8 showing a less than 3 mm side-to-side difference. The 1 patient with 6 mm of side-to-side difference was the only clinical failure.

It has always been recommended that primary repair of the ACL should be performed in the acute setting because this is correlated with better tissue quality.6 Genelin et al.4 performed surgery within a week in all patients, whereas DiFelice et al.5 performed surgery after a mean of 39 days (range, 10-93 days). However, a closer look at the latter study reveals that some patients underwent surgery 2 or 3 months after injury, and still reported good outcomes. This introduces the possibility that it might be that tear location (i.e., proximal) and tissue quality (i.e., good to excellent) are more important factors than the acuity of repair after injury, although it seems that there is likely a correlation between these factors.6

There are several advantages of arthroscopic primary repair over reconstruction when dealing with proximal ACL tears (Table 3). The arthroscopic primary repair technique has the benefit of being minimally invasive without the need for graft harvesting, or its potential complications. Furthermore, with primary repair, the native ligament is maintained with advantages of preserving blood supply and native biology of the ligament. Preserving the original ligament, along with its neural elements, may also contribute to maintaining knee proprioception because studies have shown that the ACL plays an important role in this. Finally, translational research has suggested that primary repair may prevent osteoarthritis,7 which is important because progression of osteoarthritis is reported to occur in up to 70% of patients at long-term follow-up after ACL reconstruction.8 One limitation of this technique is that it can only be performed in patients with proximal ACL tears. For most midsubstance tears, either augmented repair with a hamstring graft or ACL reconstruction would need to be performed.

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Arthroscopic Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Repair

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Quick procedure (45-60 min) | Only in the selective group of patients |

| Minimally invasive | Long-term outcomes (>5 yr) unknown |

| No graft harvesting complications | More difficult in the chronic setting |

| Does not burn bridges for later ACL reconstruction | |

| Growth plate-sparing treatment for pediatric patients | |

| Faster recovery than ACL reconstruction | |

| Prevents osteoarthritis in animal studies7 | |

| Theoretically preserves proprioception | |

| Theoretically preserves native kinematics |

In conclusion, historical results of primary repair were mixed, and this could partially be attributed to inappropriate patient selection, relatively invasive surgery, and postoperative immobilization.1, 2, 6 Currently, however, better results of primary ACL repair are being reported due to improved patient selection that is enabled by magnetic resonance imaging, less invasive surgical techniques (i.e., arthroscopy), and rehabilitation focusing on early ROM.4, 5 In this article, we described the technique of arthroscopic suture anchor primary repair of proximal ACL tears and we feel that this technique should be in the armamentarium of all orthopaedic surgeons who treat ligament injuries of the knee. Although this technique is effective for all age groups, especially strong consideration should be given to using it for children given its conservative nature.9

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interests or sources of funding: G.S.D. receives support from Arthrex.

Supplementary Data

Step-by-step surgical technique video from an arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from both the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The video illustrates the surgical technique of an arthroscopic, suture anchor, primary anterior cruciate ligament repair for patients with a proximal tear.

References

- 1.Sherman M.F., Lieber L., Bonamo J.R., Podesta L., Reiter I. The long-term followup of primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Defining a rationale for augmentation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:243–255. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feagin J.A., Jr., Curl W.W. Isolated tear of the anterior cruciate ligament: 5-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4:95–100. doi: 10.1177/036354657600400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odensten M., Lysholm J., Gillquist J. Suture of fresh ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. A 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:270–272. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genelin F., Trost A., Primavesi C., Knoll P. Late results following proximal reinsertion of isolated ruptured ACL ligaments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:17–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01552153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiFelice G.S., Villegas C., Taylor S.A. Anterior cruciate ligament preservation: Early results of a novel arthroscopic technique for suture anchor primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2162–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donoghue D.H. Surgical treatment of fresh injuries to the major ligaments of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32 A:721–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray M.M., Fleming B.C. Use of a bioactive scaffold to stimulate anterior cruciate ligament healing also minimizes posttraumatic osteoarthritis after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1762–1770. doi: 10.1177/0363546513483446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajuied A., Wong F., Smith C. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and radiologic progression of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2242–2252. doi: 10.1177/0363546513508376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frosch K.H., Stengel D., Brodhun T. Outcomes and risks of operative treatment of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament in children and adolescents. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:1539–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Step-by-step surgical technique video from an arthroscopic view of a left knee, viewed from both the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The video illustrates the surgical technique of an arthroscopic, suture anchor, primary anterior cruciate ligament repair for patients with a proximal tear.