Abstract

PURPOSE: The monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) has been shown to be associated with the prognosis of various solid tumors. This study sought to evaluate the important value of the MLR in ovarian cancer patients. METHODS: A total of 133 ovarian cancer patients and 43 normal controls were retrospectively reviewed. The patients' demographics were analyzed along with clinical and pathologic data. The counts of peripheral neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets were collected and used to calculate the MLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR). The optimal cutoff value of the MLR was determined by using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. We compared the MLR, NLR, and PLR between ovarian cancer and normal control patients and among patients with different stages and different grades, as well as between patients with lymph node metastasis and non–lymph node metastasis. We then investigated the value of the MLR in predicting the stage, grade, and lymph node positivity by using logistic regression. The impact of the MLR on overall survival (OS) was calculated by Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. RESULTS: Statistically significant differences in the MLR were observed between ovarian cancer patients and normal controls. However, no difference was found for the NLR and PLR. Highly significant differences in the MLR were found among patients with different stages (stage I-II and stage III-IV), grades (G1 and >G1), and lymph node metastasis status. The MLR was a significant and independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis, as determined by logistic regression. The optimal cutoff value of the MLR was 0.23. We also classified the data according to tumor markers (CA125, CA199, HE4, AFP, and CEA) and conventional coagulation parameters (International Normalized Ratio [INR] and fibrinogen). Highly significant differences in CA125, CA199, HE4, INR, fibrinogen levels, and lactate dehydrogenase were found between the low-MLR group (MLR ≤ 0.23) and the high-MLR group (MLR > 0.23). Correspondingly, dramatic differences were observed between the two groups in OS. CONCLUSION: Our results show that the peripheral blood MLR before surgery could be a significant predictor of advanced stages, advanced pathologic grades, and positive lymphatic metastasis in ovarian cancer patients.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer and one of the most important causes of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [1]. Fewer than half of patients survive for more than 5 years after diagnosis. More than 75% of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage after menopause because early-stage disease is usually asymptomatic, and the symptoms of late-stage disease are nonspecific [2]. Given the poor prognosis of ovarian cancer, a method for accurately predicting the prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer after curative surgical resection is necessary to improve patient survival [3], [4].

Owing to increasing evidence regarding the role of inflammation in cancer biology, a systemic inflammatory response has been found to have prognostic significance in a variety of cancers. Kawata et al. have reported that lymphocyte infiltration around the tumor is associated with a better prognosis in HCC [5], whereas the presence of neutrophils in the tumor stroma is associated with a poor prognosis [6]. Likewise, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a predictor of inflammatory status, has been shown to be an effective prognostic marker for many solid tumors [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. In addition to neutrophils and lymphocytes, monocytes are another important type of leucocyte. Studies have shown that monocytes are an independent prognostic factor, and a higher number of monocytes predict a poor prognosis, similar to the role of neutrophils in predicting prognosis. The monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), i.e., the monocyte count divided by the lymphocyte count, has recently been shown to be a much more efficient prognostic predictor in many solid tumors.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the MLR's interindividual differences and its diagnostic efficiency, feasibility, and predictive value for patients with ovarian cancer.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective analysis was conducted by using the clinical data obtained from ovarian cancer patients who underwent surgical resection at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, between January 2011 and March 2016. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai First People's Hospital. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study.

The cases of 133 ovarian cancer patients and 43 normal controls were retrospectively reviewed. The clinical stage of ovarian cancer was determined according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage. The selection criteria for patients were as follows: 1) ovarian cancer confirmed by pathology; 2) no preoperative treatments, such as radiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy; 3) no coexisting cancers or prior cancers within the previous 5 years; 4) complete clinical, laboratory, imaging, and follow-up data; 5) no evidence of sepsis [7]; 6) no autoimmune disease or treatment with steroids; and 7) no hematological disorders or treatment that could result in an elevated MLR or NLR, for example, the administration of hematopoietic agents, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, within 1 month before surgery. Routine blood tests, routine coagulation tests, and measurements of tumor markers (CA125, CA199, HE4, AFP, and CEA) were performed on the day before surgery. The normal controls are the healthy women aged 35 to 60 years. The MLR, NLR, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were defined as the ratio of the absolute peripheral blood monocyte and lymphocyte counts, absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, and absolute platelet and lymphocyte counts, respectively.

Data, including information on patient demographics, were collected for analysis. The clinicopathologic variables, including age, FIGO stage, histologic grade, lymph node metastasis, and CA-125 levels, were obtained retrospectively from patient medical records. Each cytoreduction was principally aimed at maximal tumor resection without a visible residual tumor. If technically achievable, all visible cancer was resected to achieve optimal tumor debulking, leaving a residual tumor with a maximal diameter of ≤1 cm [40].

We determined the optimized MLR cutoff values for predicting survival outcomes using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the best MLR cutoff value for diagnosis was 0.23. Patients were grouped according to the results of the ROC curve analysis, as follows: MLR-low (MLR ≤ 0.23) and MLR-high (MLR > 0.23). Differences in cancer- and host-related risk factors, including age, FIGO stage, histologic grade, optimal debulking (OD), serum CA-125 levels and overall survival (OS), between the MLR-low and MLR-high groups were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 19.0 software (Chicago, IL). After logarithmic transformations of the MLR, NLR, and PLR, the log-transformed data were close to a normal distribution. Therefore, we used the log-transformed data for statistical analysis. t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to analyze the data of two independent groups or three and four groups, respectively. To account for their effects on the relationships between the MLR and the stages, histological types, grades, lymphatic metastasis, and OD, all variables were included in a binary logistic regression analysis. The OS was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. A P value of < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The Clinical Baseline Characteristics of Ovarian Cancer Patients

The baseline characteristics of the patients are displayed in Table 1. Serous adenocarcinoma was the most common subtype (65.41%), and histological grade 3 was the most frequent grade (42.86%) in our cohort. In total, 37 (27.82%), 27 (20.30%), 65 (48.87%), and 4 (3.01%) patients had stage I, II, III, and IV disease, respectively. Additionally, 22 (16.54%) patients had lymphatic metastasis. OD was performed in 127 (95.49%) patients.

Table 1.

The Clinical Baseline Characteristics of Ovarian Patients

| Variable | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 53.27 ± 13.57 (20-82) |

| Histological type, n (%) | 133 (100%) |

| Serous | 87 (65.41%) |

| Mucinous | 14 (10.53%) |

| Endometrioid | 10 (7.52%) |

| Clear cell | 5 (3.76%) |

| Others⁎ | 17 (12.78%) |

| Differentiation, n (%) | 133 (100%) |

| G1 | 24 (18.04%) |

| G2 | 52 (39.10%) |

| G3 | 57 (42.86%) |

| Stage, n (%) | 133 (100%) |

| I | 37 (27.82%) |

| II | 27 (20.30%) |

| III | 65 (48.87%) |

| IV | 4 (3.01%) |

| Lymphatic metastasis, n (%) | 133 (100%) |

| Negative | 111 (83.46%) |

| Positive | 22 (16.54%) |

| Optimal debulking, n (%) | 133 (100%) |

| No | 6 (4.51%) |

| Yes | 127 (95.49%) |

Others: including immature teratoma (three cases), granulosa cell tumor (three cases), endodermal sinus tumor (three cases), undifferentiated tumor (three cases), carcinoid tumor (three case), squamous cell carcinoma (two case).

The Hematological Baseline Characteristics of Ovarian Cancer Patients

The median neutrophil, monocyte, and platelet counts were 67.63 × 10^9/l, 6.04 × 10^9/l, and 24.37 × 10^9/l, respectively. The NLR, MLR, and PLR were 3.73, 0.30, and 225.96, respectively. The values for the coagulation system factor, d-dimer, prothrombin time (PT), International Normalized Ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin time (TT), and fibrinogen were 2.43, 11.69, 0.99, 27.03, 18.43, and 3.49, respectively. (Table 2). The median serum levels of the tumor markers CA125, CA199, AFP, CEA, and HE4 were 1092.36 U/ml, 72.89 U/ml, 16.95 U/ml, 8.29 U/ml, and 455.57 U/ml, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical and Test Characteristics of Ovarian Cancer Population

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| CA-125 (U/ml) | 1092.36 ± 94.53 |

| CA-199(U/ml) | 72.89 ± 16.27 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 16.95 ± 4.49 |

| CEA(ng/ml) | 8.29 ± 2.70 |

| HE4 (pmol/l)⁎ | 455.57 ± 39.47 |

| WBC (⁎109/l) | 6.59 ± 3.20 |

| N (%) | 67.63 ± 11.59 |

| L (%) | 24.37 ± 10.04 |

| M (%) | 6.04 ± 2.55 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 119.87 ± 17.94 |

| Platelet (⁎109/l) | 279.57 ± 112.24 |

| Ln NLR | 1.07 ± 0.59 |

| Ln MLR | -1.45 ± 0.52 |

| Ln PLR | 5.22 ± 0.57 |

| d-Dimer (mg/l) | 2.43 ± 1.01 |

| PT (s) | 11.69 ± 1.39 |

| INR | 0.99 ± 0.09 |

| APTT (s) | 27.03 ± 4.00 |

| TT (s) | 18.43 ± 2.69 |

| Fibrinogen, FIG (mg/l) | 3.49 ± 1.06 |

| LDH (U/l) | 196.64 ± 88.8 |

Detected after 2013.

MLR, NLR, and PLR between Ovarian Cancer Patients and Controls

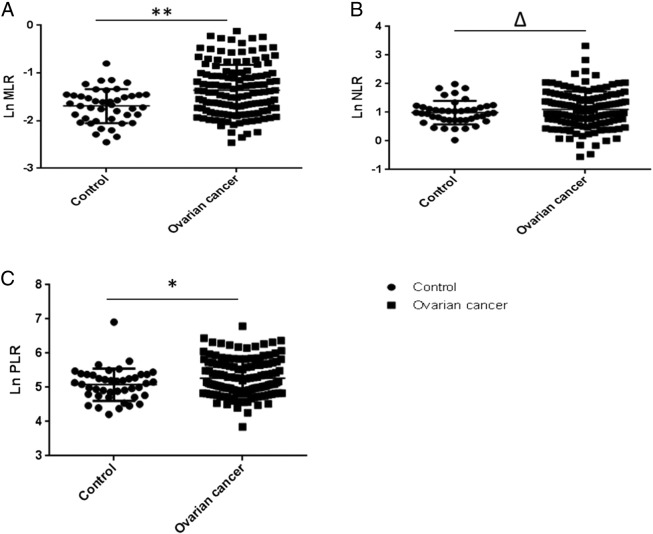

When we compared the MLR and PLR between ovarian cancer patients and controls, significant differences were observed (P = .0003 and P = .046). However, no differences in the NLR were found between ovarian cancer patients and normal controls (P = .304) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

High MLR in ovarian cancer patients.

(A, B, and C) The Ln MLR, Ln NLR, and Ln PLR between the control group and the ovarian cancer group, respectively. **P = .0003; *P = .039; ∆P > .05.

MLR as an independent Predictor of Ovarian Cancer and Is Positively Correlated with CA125

Given that the MLR was different between the control group and ovarian cancer group, we sought to determine whether the MLR could be a predictor of ovarian cancer. In the binary logistic regression, the MLR was identified as an independent predictor or risk factor of ovarian cancer [odds ratio (OR) = 8.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.65-27.71] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Predictors of Ovarian Cancer in the Binary Logistic Regression Analysis

| β | P | OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLR | 2.14 | .00 | 8.50 | 2.65-27.71 |

| NLR | −1.49 | .02 | 0.23 | 0.07-0.79 |

| PLR | 0.689 | .20 | 1.92 | 0.70-5.64 |

All analyzed data were Ln (original data) transformed from the original data and tested with binary logistic regression.

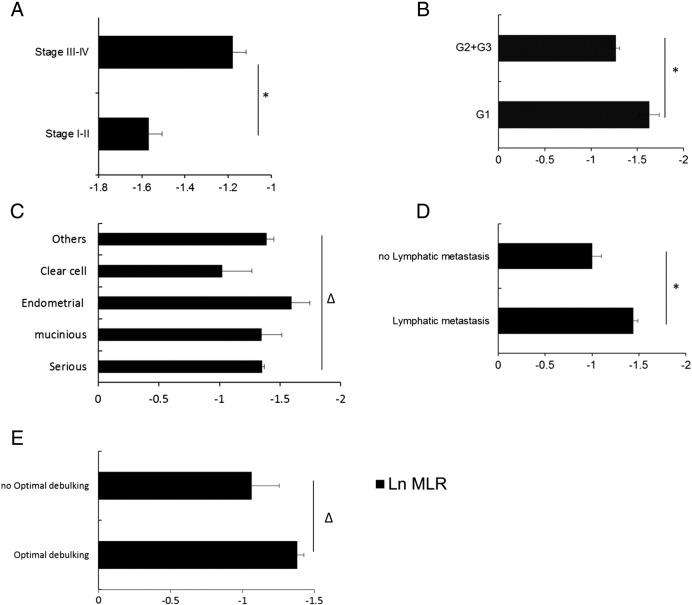

Then, we examined the ROC curve of the MLR in distinguishing the control from ovarian cancer patients. In the ROC analysis, the area under the curve is 0.68 (95% CI, 0.59-0.76). A cutoff of 0.23 was identified to reach a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 90% from this study cohort (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of the MLR for the prediction of ovarian cancer.

*ROC analysis of the control group MLR and the ovarian cancer group MLR.

AUC, area under curve.

Because CA125 is an important maker of ovarian cancer, we next investigated the relationship with MLR by Spearman's rank correlation analysis using original data of MLR and CA125. There was a significant positive correlation between MLR and CA125 (r = 0.46, P = .00).

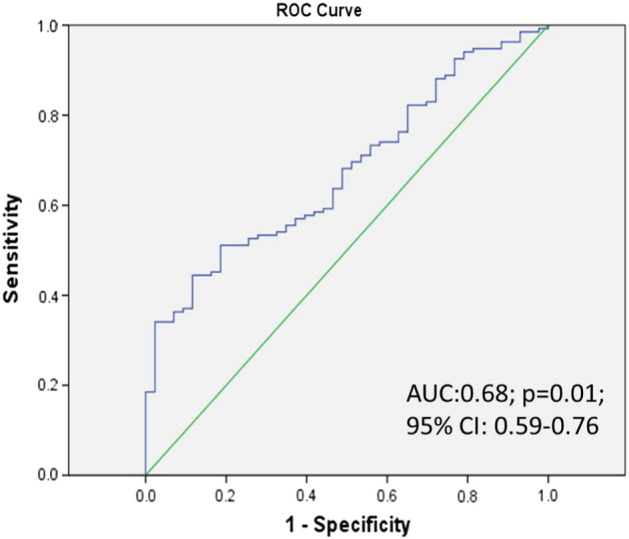

The Differences in the MLR across Stages, Histological Types, Grades, Lymphatic Metastasis, and OD

Next, we investigated differences in the MLR with respect to histological types, grades, stages, lymphatic metastasis, and OD. As shown in Figure 3, significant differences were found for categorical variables including FIGO stages (P < .0001), histological grades (P = .0076), and lymphatic metastasis (P = .0004), but not including histological types (P = .4034) and OD (P = .1056).

Figure 3.

Differences in the MLR among various stages, histological types, pathologic grades, lymphatic metastasis, and OD.

(A) *P < .0001(t test); (B) *P = .0076 (t test); (C) ∆P = .4034, one-way ANOVA; (D) P = .0004 (t test); (E) ∆P = .1056; one-way ANOVA.

The MLR was an independent risk factor for advanced stages, lymphatic metastasis, and advanced pathological grades in ovarian cancer patients.

Because the MLR was significantly different among patients with different FIGO stages, lymphatic metastasis, and tumor pathological grades, we further investigated the association between the MLR with the stages, lymphatic metastasis, and grades by using binary logistic regression. As shown in Table 4, the MLR was significantly associated with stages, lymphatic metastasis, and grades. All of the three β values and OR values were >1, indicating that the MLR was a significant independent risk factor for advanced stages, lymphatic metastasis, and advanced grades.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Estimates (β Coefficients and 95% CI) of the Association between MLR and Stages, Lymphatic Metastasis, and Histological Grades

| β | P | OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | 1.15 | .002 | 3.15 | 1.55-6.44 |

| Lymphatic metastasis | 1.55 | .000 | 4.70 | 1.880-11.74 |

| Histological grades | 1.32 | .01 | 3.72 | 1.36-10.17 |

All analyzed data were Ln (original data) transformed from the original data and tested with binary logistic regression. As in Figure 2, the stages were classified as stage I-II and stage III-IV, and β = 1.15 > 1, OR = 3.15 > 1, indicating that the MLR was a significant independent risk factor for advanced stage in ovarian cancer patients. Similarly, the MLR was also a significantly important predictor for lymphatic metastasis (β = 1.55 > 1, OR = 4.70 > 1). The pathology grades were divided into two groups, G1 and >G1 (G2 + G3), and tested with binary logistic regression. Because β = 1.32 > 1 and OR = 3.72 > 1, the MLR was also shown to be a significant independent risk factor of higher pathology grades.

Initially, we assessed differences in the MLR in three pathologic grades by using one-way ANOVA. We found that the MLR was significantly different between G1 and G2 and between G1 and G3. However, no significant differences were observed between G2 and G3. Therefore, we merged the data of G2 and G3 into one group, the “>G1” group, and reanalyzed the data with the results shown in Figure 3B. Furthermore, logistic regression was performed and showed that the grade is associated with MLR (P = .01, β = 1.32, OR = 3.72).

Differences in the Baseline Characteristics between the MLR-Low and MLR-High Groups

The optimal cutoff value of the MLR was 0.23 (Figure 2). The MLR-low and MLR-high groups included 64 (48.12%) and 69 (51.88%) patients, respectively. To evaluate the relevance of the MLR, we assessed differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients according to the different MLR categories. Significant differences between the MLR-low and MLR-high groups were found for the following continuous variables: serum CA125 levels (P = .000), serum CA199 levels (P = .033), HE4 levels (P = .005), percentage of neutrophils (P = .000), percentage of lymphocytes (P = .000), percentage of monocytes (P = .000), NLR (P = .000), MLR (P = .000), PLR (P = .000), INR (P = .000), fibrinogen (P = .000), and lactate dehydrogenase (P = .016) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Clinical and Hematologic Characteristics of Ovarian Cancer Patients, according to the Cutoff Value of the MLR

| Variable | MLR-Low (≤0.23) |

MLR-High (>0.23) |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age (years) | 64 | 49.81 ± 13.83 | 69 | 56.00 ± 12.60 | .008 |

| CA-125 (U/ml) | 64 | 604.25 ± 1200.30 | 69 | 1557.93 ± 1790.81 | .001 |

| CA-199 (U/ml) | 64 | 32.37 ± 84.37 | 69 | 113.41 ± 379.59 | .108 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 64 | 31.25 ± 171.52 | 69 | 2.87 ± 2.58 | .205 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 64 | 3.45 ± 10.23 | 69 | 13.21 ± 50.99 | .151 |

| HE4 (pmol/l)⁎ | 38 | 240.84 ± 315.98 | 32 | 710.56 ± 867.76 | .006 |

| WBC (⁎109/l) | 64 | 5.99 ± 2.06 | 69 | 7.14 ± 3.96 | .039 |

| N (%) | 64 | 62.57 ± 10.44 | 69 | 72.33 ± 10.79 | .000 |

| L (%) | 64 | 30.53 ± 8.66 | 69 | 18.65 ± 7.73 | .000 |

| M (%) | 64 | 4.93 ± 1.35 | 69 | 7.06 ± 2.97 | .000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 64 | 124.42 ± 15.49 | 69 | 115.65 ± 19.33 | .005 |

| Platelet (⁎109/l) | 64 | 246.34 ± 89.99 | 69 | 310.39 ± 123.54 | .001 |

| d-Dimer (mg/l) | 64 | 0.93 ± 0.82 | 69 | 3.70 ± 2.24 | .001 |

| PT (s) | 64 | 11.54 ± 0.83 | 69 | 11.83 ± 1.78 | .232 |

| INR | 64 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 69 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | .018 |

| APTT (s) | 64 | 26.51 ± 4.14 | 69 | 27.51 ± 3.86 | .152 |

| TT (s) | 64 | 18.61 ± 2.28 | 69 | 18.25 ± 3.06 | .445 |

| Fibrinogen, FIG (mg/l) | 64 | 3.08 ± 0.78 | 69 | 3.88 ± 1.16 | .000 |

| LDH (U/l) | 64 | 180.60 ± 84.10 | 69 | 216.80 ± 84.88 | .016 |

HE4 was detected after 2013.

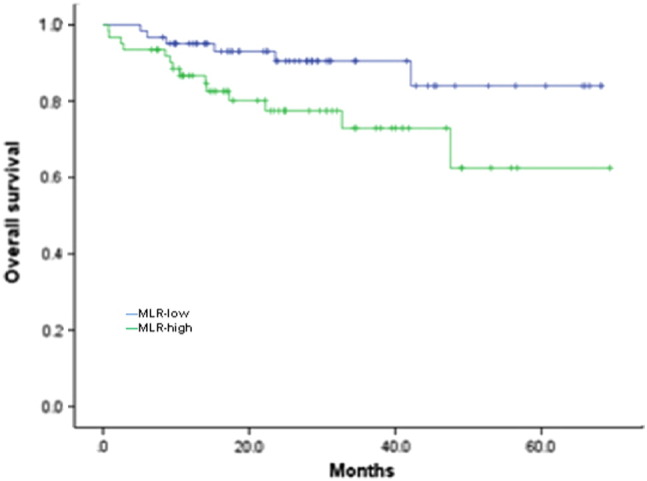

MLR Predicted OS in 124 Patients with Ovarian Cancer

After a median follow-up of 23.617 months (range, 0.767-69.4 months), there were 6 patients who died in the MLR-low group, and there were 14 patients who died in the MLR-high group. The total missed follow-up rate was 6.767%. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, high MLR was significantly associated with a lower OS rate and higher mortality in ovarian cancer (P = .037) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS in patients with ovarian cancer.

Significant differences were found between MLR-low and MLR-high groups (P = .037).

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer and is one of the major causes of cancer-related death in women worldwide. The high mortality is partly due to difficulties in early diagnosis and the development of metastases. Given this cancer's poor prognosis, methods for accurately predicting risk factors that affect cancer severity and early diagnosis are required to improve patient survival rates.

In recent years, several prognostic indicators derived from peripheral blood, such as the MLR, NLR, and PLR, have been widely investigated as useful prognostic markers in cancers. Despite inconsistent results, these markers have been reported to have significant diagnostic and prognostic value in a wide variety of cancers. The MLR has been suggested to be associated with survival in patients with malignant lymphomas and many solid tumors, such as head and neck, breast [14], lung, esophageal, gastric, colorectal [15], [16], pancreatic, bladder [6], and cervical cancers [5]. A high MLR was associated with poor OS in previous reports, and the MLR can be considered to be a potential surrogate biomarker in various cancers. Although the mechanisms of the association between a higher MLR and a poorer prognosis have not been fully clarified, the MLR may reflect the balance between the favorable role of lymphocytes and the unfavorable effect of monocytes with respect to cancer progression.

In this study, the MLR was significantly higher in the ovarian cancer group than in the control group. The higher MLR indicated lower lymphocyte or higher monocyte levels in the peripheral blood of ovarian cancer patients. Lymphocytes play important roles in the defense against cancer cells by inducing cytotoxic cell death and suppressing tumor cell proliferation and migration. Many types of lymphocytes, such as T cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages, have been shown to infiltrate ovarian cancer [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. It is well accepted that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes establish a defense barrier against cancer dissemination. Therefore, decreased lymphocyte counts in the blood and tumor stroma lead to a downregulation of the immune response against tumors [5]. Moreover, a decreased lymphocyte count in the blood has been identified as an independent prognostic factor for OS in various cancers. Additionally, the pretreatment number of peripheral blood monocytes has been shown to be correlated with poor prognosis in patients with various types of cancers. After recruitment into tumor tissue, monocytes differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [22]. Evidence from clinical and experimental studies has indicated that TAMs promote solid-tumor progression and metastasis, and monocytes in the peripheral blood may reflect the formation or presence of TAMs, which are a prominent component of the mononuclear leukocyte population of solid tumors and display an ambivalent relationship with tumors. TAMs are educated by the tumor microenvironment, and they facilitate angiogenesis, matrix breakdown, and tumor-cell motility, all of which are elements of the metastatic process. During an inflammatory response, macrophages also produce many compounds, ranging from mutagenic oxygen and nitrogen radicals to angiogenic factors that can contribute to cancer initiation and promotion. As such, monocytes/TAMs can promote solid-tumor progression and metastasis [24], [25], [26]. Furthermore, ovarian cancer also has the ability to escape the immune system because pathological interactions between cancer cells and host immune cells in the tumor microenvironment create an immunosuppressive network that promotes tumor growth and protects the tumor from the immune system [24], [25]. Therefore, we speculated that the higher MLR of ovarian cancer patients may indicate increased monocyte differentiation and infiltration of TAMs, which are involved in ovarian cancer cell immune escape, thereby stimulating ovarian cancer progression and metastasis. However, this possibility requires further study.

Our results also showed, via logistic regression, that a higher MLR was observed in patients with a higher stage and grade, as well as those with positive lymphatic metastasis, and is therefore an independent risk factor for advanced stage, advanced pathologic grade, and positive lymphatic metastasis. In most studies, the cutoff values for the MLR were determined by ROC curve analysis. Our cutoff point of MLR between normal and ovarian cancer was 0.23, also determined by ROC curve analysis. In the present study, significant differences were observed in the CA125, CA199, HE4, INR, fibrinogen levels, and lactate dehydrogenase between the MLR-low (≤0.23) and MLR-high (>0.23) groups (P < .0001). CA125 and CA199 are antibodies that are considered to be ovarian cancer biomarkers, and malignant cancer patients have hypercoagulation conditions with higher fibrinogen levels. The association of MLR with cancer survival has been reported for several cancers, such as bladder cancer, endometrial cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [27], [28], [29]; however, it was rarely reported in ovarian cancer. Our result revealed that lower MLR levels were associated with favorable OS of ovarian cancer (P = .037). These results were in accordance with other researches.

Unexpectedly, we found that the MLR was significantly associated with coagulation conditions. It is well known that the hemostatic components and the cancer biology are interconnected in multiple ways. The hemostatic factors play a role in tumor progression. Cancer cells are able to activate the coagulation system, release procoagulant factor, microparticles that directly activate the coagulation cascade. Our results suggested a close relationship between immune regulation and hemostatic system, which may be involved in tumor progression. But it needed further research.

From these data, we conclude that the MLR is involved in immune escape and may reflect the immune regulation status of ovarian cancer. When the MLR is increased, more monocytes/TAMs are recruited and educated, more CA125 and CA199 are produced, and increased coagulation is established, thus supporting an important role of the MLR in ovarian cancer.

The strength of the current study is that it is the first attempt to evaluate the predictive value of the MLR in ovarian cancer patients. Moreover, the value of the MLR was evaluated together with previously validated biomarkers, namely, the NLR and PLR. Some limitations were present in this study, including its retrospective nature and the inclusion of a relatively small number of patients. Another limitation is that the MLR is a nonspecific marker of inflammation, and the results may be affected by the presence of other systemic diseases. Additional large-scale and standard investigations should be conducted to apply this convenient, simple, and inexpensive prognostic factor for risk stratification.

Conclusion

This study was the first attempt to assess the predictive value of the MLR in ovarian cancer patients. In this study, we found that an elevated MLR reflected patient immune conditions and was a strong risk factor for advanced ovarian cancer stages, pathologic grades, lymphatic metastasis, and OS rate. Therefore, the MLR may be clinically reliable and useful for the accurate prediction of ovarian cancer initiation and subsequently for patient prognosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81001154, Y.-Y. He and no. 81172478, X.-W. Xi), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (no. 11QA1405200, Y.-Y. He), and Nature Science Foundation of Shanghai (no. 13ZR1459600, L.-N. Zhou).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This study was sponsored by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81001154, Y.-Y. He and no. 81172478, X.-W. Xi), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (no. 11QA1405200, Y.-Y. He), and Nature Science Foundation of Shanghai (no. 13ZR1459600, L.-N. Zhou).

Contributor Information

Xiaowei Xi, Email: xixiaowei1966@126.com.

Yinyan He, Email: heyinyan0228@126.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polterauer S, Vergote I, Concin N, Braicu I, Chekerov R, Mahner S, Woelber L, Cadron I, Van Gorp T, Zeillinger R. Prognostic value of residual tumor size in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer FIGO stages IIA-IV: analysis of the OVCAD data. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:380–385. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31823de6ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L. Nutritional factors in ovarian cancer survival. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:580–586. doi: 10.1080/01635580902825670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawata A, Une Y, Hosokawa M, Uchino J, Kobayashi H. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1992;22:256–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Wang L, Liu Y, Wang S, Shang P, Gao Y, Chen X. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio before platelet-lymphocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with cervical cancer treated with initial radical surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1319–1325. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermanns T, Bhindi B, Wei Y, Yu J, Noon AP, Richard PO, Bhatt JR, Almatar A, Jewett MA, Fleshner NE. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as predictor of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:444–451. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng JF, Huang Y, Chen QX. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is superior to neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictive factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu SJ, Shen SL, Li SQ, Hua YP, Hu WJ, Liang LJ, Peng BG. Prognostic value of preoperative peripheral neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after radical hepatectomy. Med Oncol. 2013;30:721. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braicu EI, Sehouli J, Richter R, Pietzner K, Lichtenegger W, Fotopoulou C. Primary versus secondary cytoreduction for epithelial ovarian cancer: a paired analysis of tumour pattern and surgical outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Jiang R, Liu WS, Liu Q, Xu M, Feng QS, Chen LZ, Bei JX, Chen MY, Zeng YX. A large cohort study reveals the association of elevated peripheral blood lymphocyte-to- monocyte ratio with favorable prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ni XJ, Zhang XL, Ou-Yang QW, Qian GW, Wang L, Chen S, Jiang YZ, Zuo WJ, Wu J, Hu X. An elevated peripheral blood lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts favorable response and prognosis in locally advanced breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa T, Ishihara S, Kawai K, Kazama S, Yamaguchi H, Sunami E, Kitayama J, Watanabe T. Impact of a lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in stage IV colorectal cancer. J Surg Res. 2015;199:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stotz M, Pichler M, Absenger G, Szkandera J, Arminger F, Schaberl-Moser R, Samonigg H, Stojakovic T, Gerger A. The preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with stage III colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:435–440. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang GM, Zhu Y, Luo L, Wan FN, Zhu YP, Sun LJ, Ye DW. Preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of overall survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:8537–8543. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Zhang F, Sheng XG, Zhang SQ. Decreased pretreatment lymphocyte/monocyte ratio is associated with poor prognosis in stage Ib1-IIa cervical cancer patients who undergo radical surgery. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1355–1362. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S82174. [eCollection 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu P, Shen H, Wang G, Zhang P, Liu Q, Du J. Prognostic significance of systemic inflammation-based lymphocyte- monocyte ratio in patients with lung cancer: based on a large cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyahara Y, Odunsi K, Chen W, Peng G, Matsuzaki J, Wang RF. Generation and regulation of human CD4+ IL-17-producing T cells in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15505–15510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710686105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawamura K, Komohara Y, Takaishi K, Katabuchi H, Takeya M. Detection of M2 macrophages and colony-stimulating factor 1 expression in serous and mucinous ovarian epithelial tumors. Pathol Int. 2009;59:300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, Bundy B, Nishikawa H, Qian F, Jungbluth AA, Frosina D, Gnjatic S, Ambrosone C. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvero AB, Montagna MK, Craveiro V, Liu L, Mor G. Distinct subpopulations of epithelial ovarian cancer cells can differentially induce macrophages and T regulatory cells toward a pro-tumor phenotype. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:256–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitamura T, Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Immune cell promotion of metastasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:73–86. doi: 10.1038/nri3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavin Y, Mortha A, Rahman A, Merad M. Regulation of macrophage development and function in peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:731–744. doi: 10.1038/nri3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leavy O. Memories of the dead give strength. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner TB, Buchsbaum DJ, Straughn JM, Jr., Randall TD, Arend RC. Ovarian cancer and the immune system — the role of targeted therapies. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Felice F, Marchetti C, Palaia I, Musio D, Muzii L, Tombolini V, Panici PB. Immunotherapy of ovarian cancer: the role of checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunol Res. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/191832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida T, Kinoshita H, Yoshida K, Mishima T, Yanishi M, Inui H, Komai Y, Sugi M, Inoue T, Murota T. Prognostic impact of perioperative lymphocyte-monocyte ratio in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10067–10074. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eo WK, Kwon S, Koh SB, Kim MJ, YI J, Lee JY, Suh DS, Kim KH, Kim HY. The lymphocyte-monocyte ratio predicts patient survival and aggressiveness of endometrial cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7:538–545. doi: 10.7150/jca.14206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou D, Zhang Y, Xu L, Zhou Z, Huang J, Chen M. A monocyte/granulocyte to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15263. doi: 10.1038/srep15263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]