Abstract

Background & Aims

No treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been approved by regulatory agencies. We performed a randomized controlled trial to determine whether 52 weeks of cysteamine bitartrate delayed release (CBDR) reduces the severity of liver disease in children with NAFLD.

Methods

We performed a double-masked trial of 169 children with NAFLD Activity Scores ≥ 4 at 10 centers. From June 2012 to January 2014, the patients were randomly assigned to receive CBDR or placebo twice daily (300 mg for ≤65 kg, 375 mg for >65–80 kg, 450 mg for >80 kg) for 52 weeks. The primary outcome from the intention to treat analysis was improvement in liver histology over 52 weeks, defined as a decrease in NAFLD Activity Score ≥ 2 points without worsening fibrosis; patients without biopsies from week 52 (17 in the CBDR group and 6 in the placebo group) were considered non-responders. We calculated relative risks (RR) of improvement using stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel analysis.

Results

There was no significant difference between groups in the primary outcome (28% of children in the CBDR group vs 22% in the placebo group; RR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.8–2.1; P=.34). However, children receiving CBDR had significant changes in pre-specified secondary outcomes: reduced mean levels of alanine aminotransferase (reduction of 53±88 U/L vs a reduction of 8±77 U/L in the placebo group; P=.02) and aspartate aminotransferase (reduction of 31±52 vs a reduction of 4±36 U/L in the placebo group; P=.008), and a larger proportion had reduced lobular inflammation (in 36% of patients in the CBDR group vs placebo 21% of patients in the placebo group; RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–2.9; P=.03). In a post-hoc analyses, of children ≤65 kg, those taking CBDR had a 4-fold better chance of histologic improvement (observed in 50% of children in the CBDR group vs 13% in the placebo group; RR, 4.0; 95% CI, 1.3–12.3; P=.005).

Conclusions

In a randomized trial, we found that 1 year of CBDR did not reduce overall histologic markers of NAFLD compared with placebo in children. Children receiving CBDR did, however, have significant reductions in serum levels of aminotransferase levels and lobular inflammation. ClinicalTrials.gov no: NCT01529268.

Keywords: Pediatrics, ALT, AST, obesity

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 7 million children in the United States have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) which is now the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the pediatric population 1. NAFLD encompasses a broad spectrum of liver disease severity ranging from isolated steatosis to steatohepatitis (NASH) with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis2. In children, NAFLD is also associated with cardiovascular, metabolic, pulmonary, and psychological disorders 3–8. There are no approved pharmacological therapies for NAFLD in children.

Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation may contribute to the pathogenesis of NASH 9. Glutathione is a major intracellular antioxidant in the liver and its depletion has been implicated in the development of hepatocellular injury in NASH 10, 11. Prevention of glutathione depletion may thus be an effective therapeutic strategy for NASH. Glutathione is a tripeptide (γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine) which is not absorbed intact as an oral agent nor does it cross cell membranes. However, ensuring an adequate supply of precursor amino acids, especially cysteine, to support intracellular glutathione synthesis is a proven strategy for preventing glutathione depletion in the liver 12, 13. Cysteamine is a small molecule (HS-CH2-CH2-NH2) which is able to cross cell membranes easily and reacts with extracellular cystine to form cysteine which is then readily taken up into cells and used to support glutathione synthesis14–16. In an open-label pilot study, 6 months of treatment with cysteamine bitartrate improved serum alanine (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels and increased adiponectin in children with NAFLD 17.

Based upon these preliminary data, a phase 2b clinical trial, Cysteamine bitartrate delayed-release for the treatment of Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Children (CyNCh), was designed to further evaluate cysteamine as a therapy for children with NAFLD. CyNCh was a multi-center, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of children ages 8 to 17 years with moderate to severe NAFLD. In order to take advantage of improved pharmacokinetics, we used cysteamine bitartrate formulated in microspheronized, delayed-release enteric-coated, core beads. The primary objective was to evaluate whether 52 weeks of treatment with cysteamine bitartrate delayed-release (CBDR) capsules would result in improvement in liver disease severity. Because of the lack of a validated non-invasive measure for the severity of NAFLD, CyNCh was designed with liver histology as the primary outcome. Notably, CyNCh was the first clinical trial for any pediatric liver disease to use changes in liver histology as the primary outcome.

METHODS

Study Design

Children with NAFLD were enrolled at 10 Clinical Centers from June 2012 to January 2014 (see Appendix 1 for list of centers) as part of the NIH sponsored NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each Clinical Center and the Data Coordinating Center (DCC). An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) was appointed by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) to monitor the study. Parents or guardians provided written consent and all children provided written assent.

Study inclusion criteria were: children ages 8–17 years at enrollment, with histologic evidence of NAFLD based on a liver biopsy obtained within 90 days of the start of screening and no more than 120 days before randomization, and a NAFLD activity score (NAS) of ≥ 4, as scored by the individual NASH CRN pathology committee member at each study site. The median (IQR) number of days between liver biopsy and randomization was 74 (51–96). Participants also lacked evidence of other liver disease based on laboratory evaluation and liver histology. They also had to demonstrate the ability to swallow CBDR capsules. Children were excluded if they had uncompensated liver disease, poorly controlled diabetes (hemoglobin A1c >9%), or a history of other conditions that made it unsafe to participate (see Appendix 2 for full list of inclusion/exclusion criteria).

Dosing, Randomization and Treatment groups

The majority of knowledge on the pharmacology and pharmacotherapy of cysteamine comes from its use in the treatment of cystinosis. Until the approval of CBDR in 2013, immediate release cysteamine was the standard therapy for the treatment of cystinosis. For the treatment of cystinosis, the dose of immediate-release cysteamine used was 50–90 mg/kg per day divided into 4 doses up to a maximum dose of 500 mg per dose 18. The preliminary study of cysteamine for the treatment of NAFLD in children was conducted in 2009 using a new enteric-coated formulation of immediate-release cysteamine bitartrate (EC-CB) with better pharmacokinetics 17. The dosing of EC-CB was targeted to give the highest dose that each individual child with NAFLD was able to tolerate without GI side effects. The mean dose achieved was 14 mg/kg day divided twice a day. In CyNCh, the formulation of cysteamine bitartrate used was microspheronized, delayed-release enteric-coated, core beads (CBDR). Because CBDR has a lower Cmax and a more controlled delivery pattern over time than EC-CB, the target dose for CBDR was 9–12 mg/kg per day, which was by design somewhat lower than the dose of EC-CB in a prior study 19.

Eligible subjects were randomized in permuted blocks (of sizes 2 or 4) of treatments, stratified by Clinical Center and body weight at enrollment (≤65 kg, >65 kg to 80 kg, and >80 kg). The randomization plan was prepared and administered centrally by the DCC, and randomizations were done by Clinical Centers using a web-based application that verified eligibility and completeness of baseline data. Children were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either CBDR (75 mg capsules) or matching placebo capsules orally in weight adjusted doses: 300 mg twice daily for ≤65 kg, 375 mg twice daily for >65–80 kg, or 450 mg twice daily for >80 kg. Treatment duration was 52 weeks. Participants started treatment at a lower dose (75 mg twice daily for ≤65 kg, 150 mg twice daily for >65–80 kg, or 225 mg twice daily for >80 kg), which escalated weekly to the full dose during the first four weeks of treatment in order to minimize gastrointestinal side effects (see Appendix 3 for details on dose escalation). In some cases, doses were stepped down to manage side effects. Site investigators, clinical coordinators and staff, pathologists, and participants were masked to treatment assignment.

Clinical Evaluation and Follow-up

Follow-up study visits were scheduled at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 52, followed by an off-treatment visit at 76 weeks to assess safety and durability of response. The first subject was enrolled in June 2012. The final follow-up visit occurred in August 2015. At each visit, participants underwent a standard medical history and physical exam including height, weight, waist, and hip measurements; blood collection for laboratory analysis, including a hepatic panel, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel (weeks 24, 52, and 76), fasting lipid profile (weeks 24, 52, and 76), fasting serum glucose, HbA1c, and insulin (weeks 24, 52, and 76), and banking of serum and plasma. Female participants of child-bearing potential had a urine pregnancy test at each visit. Assessment of adverse events, a liver symptoms questionnaire, AUDIT alcohol questionnaire20, and study drug dispensing and return, including pill counts, were completed at each visit. The Pediatric Quality of Life version 4.021, 22 was completed at baseline as well as weeks 52 and 76. Nutritional assessment using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) was completed at baseline and 52 weeks. Liver biopsy was performed at week 52. All children received a standardized nutrition and exercise intervention consistent with the American Academy of Pediatrics 2007 Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity23. As recommended for NAFLD, lifestyle advice was provided at each study visit 24.

Liver Histology

The methods for histologic scoring of the liver tissue have been described by Kleiner, et al. 25 Briefly, in order to standardize the assessment of liver histology used for the clinical trial outcome, we used a centralized liver pathology reading by the NASH CRN Pathology Committee. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome stains were prepared from formalin-fixed tissue specimens using a central laboratory, and consensus scoring of each feature of NAFLD occurred in-person using a multi-head microscope. The NASH CRN Pathology Committee was masked as to which NASH CRN study the slides were from, whether they were from baseline vs. end of treatment, and the treatment group. The NAS for study entry was determined by a NASH CRN Pathology Committee pathologist at each Clinical Center who reviewed clinically available liver slides from the hospital at which the individual child received their care. Histologic eligibility criteria were based on the NASH CRN pathologists’ scoring of locally prepared tissue sections, but all analyses regarding treatment response were based on the centrally stained and scored baseline and 52-week liver biopsies

Histologic activity was assessed using the NAS on a scale of 0 to 8. The components of the NAS include grades of steatosis (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–3) and hepatocellular ballooning (0–2)25. Fibrosis was scored on a scale from 0–4, and portal inflammation on a scale from 0–2. Biopsies were also given a diagnosis of: not NAFLD; NAFLD, but not steatohepatitis; borderline steatohepatitis with Zone 3 pattern, borderline steatohepatitis with Zone 1 pattern; or definite steatohepatitis26.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was the proportion of children with histologic improvement in NAFLD between the baseline liver biopsy and follow-up biopsy after 52 weeks of treatment, where improvement was defined as: (1) decrease in NAS of 2 points or more and (2) no worsening of fibrosis. No worsening of fibrosis was defined as either no change or any decrease in stage.

Secondary Outcomes

Pre-specified secondary histologic outcomes included the change in score (52 weeks – baseline) in the following features: steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, portal inflammation, and fibrosis; as well as the aggregate outcomes of NAS and resolution of NASH. We also analyzed pre-specified secondary histologic outcomes as improvement in individual features defined as any numerical decrease in the grade, stage, or score. Laboratory secondary outcomes included change in aminotransferases (ALT and AST) and insulin sensitivity (52 weeks – baseline), and change over time in mean ALT and AST. Other secondary outcomes included change in anthropometric measures (weight, BMI, BMI z-score, and waist circumference), and changes in Pediatric Quality of Life. Change in weight status was defined by change in BMI z-score from baseline to week 52 as follows: 1) improved = a decrease of > 0.1; 2) stable = −0.1 to +0.1; 3) worsened = an increase of > 0.1.27–29

Statistical Analysis

The primary intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis compared the proportion of children with histologic improvement between the baseline and end-of–treatment liver biopsies in the CBDR and placebo groups. Participants who did not have an end-of-treatment liver biopsy were considered as non-responders for the purpose of the primary outcome. The primary outcome and binary secondary outcomes are presented as relative risks, derived from the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for binary outcomes stratified by clinical center and weight group. Improvement in individual histological features was based on ITT, where missing biopsies were imputed as a lack of improvement. Continuous secondary outcomes were based on complete case analysis (missing biopsies were excluded), and were analyzed using ANCOVA models relating change in the continuous outcome from baseline to 52 weeks to treatment group and to the baseline value of the outcome. The differences in distributions of adverse events, categorized by body system, were assessed for CBDR vs. placebo using Fisher’s exact tests.

In addition to the primary intention-to-treat analysis, pre-specified sensitivity analyses related to the primary outcome were conducted, including (1) complete case analysis, where missing biopsies were excluded from the analysis; (2) analysis of children who were adherent to their target dose; (3) multiple imputation for missing biopsies, where the imputation model included a treatment group indicator, baseline NAS, baseline fibrosis stage, clinic, weight stratum, age, and sex; (4) best case scenario, where missing biopsies were imputed as improved for children assigned to CBDR and not improved for children assigned to placebo; (5) worst case scenario, where missing biopsies were imputed as improved for children assigned to placebo and not improved for children assigned to CBDR.

Based upon past trial data, we projected a histological improvement rate of 25% in the placebo group and we considered a 2-fold increase (50% improved) in the rate of histological improvement in the CBDR group as the minimum clinically meaningful effect. The resulting trial sample size was 160 children to be assigned randomly with equal probability to the two treatment groups and assuming: a Type 1 error of 0.05, power of 90%, and 10% lost to follow-up in each group. Losses to follow-up were imputed as not improved in both the intention-to-treat analyses and in the sample size calculations. There were no planned subgroup analyses specified in the protocol; however, post-hoc subgroup analyses were done to explore whether or not the efficacy of CBDR varied across subgroups of patients. Logistic regression models were used for the post-hoc analyses and included terms for treatment group, subgroup, and the treatment group by subgroup interaction term. The trial had no interim analyses for efficacy; however, performance and safety data were reviewed quarterly by the DSMB. Nominal, two-sided p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant (p<0.01 required for significance of post-hoc subgroup effects); no adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. Statistical analyses were done with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata release 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Role of Funding Sources

The NASH CRN is funded by the NIDDK as a cooperative agreement. The CyNCh trial was funded as a part of the NASH CRN with partial funding provided via a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with Raptor Pharmaceuticals, who also provided CBDR and matching placebo capsules. The CyNCh trial protocol was written by a subcommittee and approved by the Steering Committee of the NASH CRN (Appendix 4). The CyNCh trial was conducted under an Investigational New Drug application (IND # 114,924) held by the NIDDK and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01529268. Data analyses were reviewed by the study investigators and the DSMB. The manuscript was written by a subcommittee and approved by the members of the Steering Committee, who assume responsibility for the conduct of the trial and integrity of the data, the overall content of the manuscript, and the decision to submit it for publication. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Raptor Pharmaceuticals provided comments on the study protocol and manuscript for consideration, but were not involved in study design, data analyses and interpretation, or writing and submission of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Study Participants

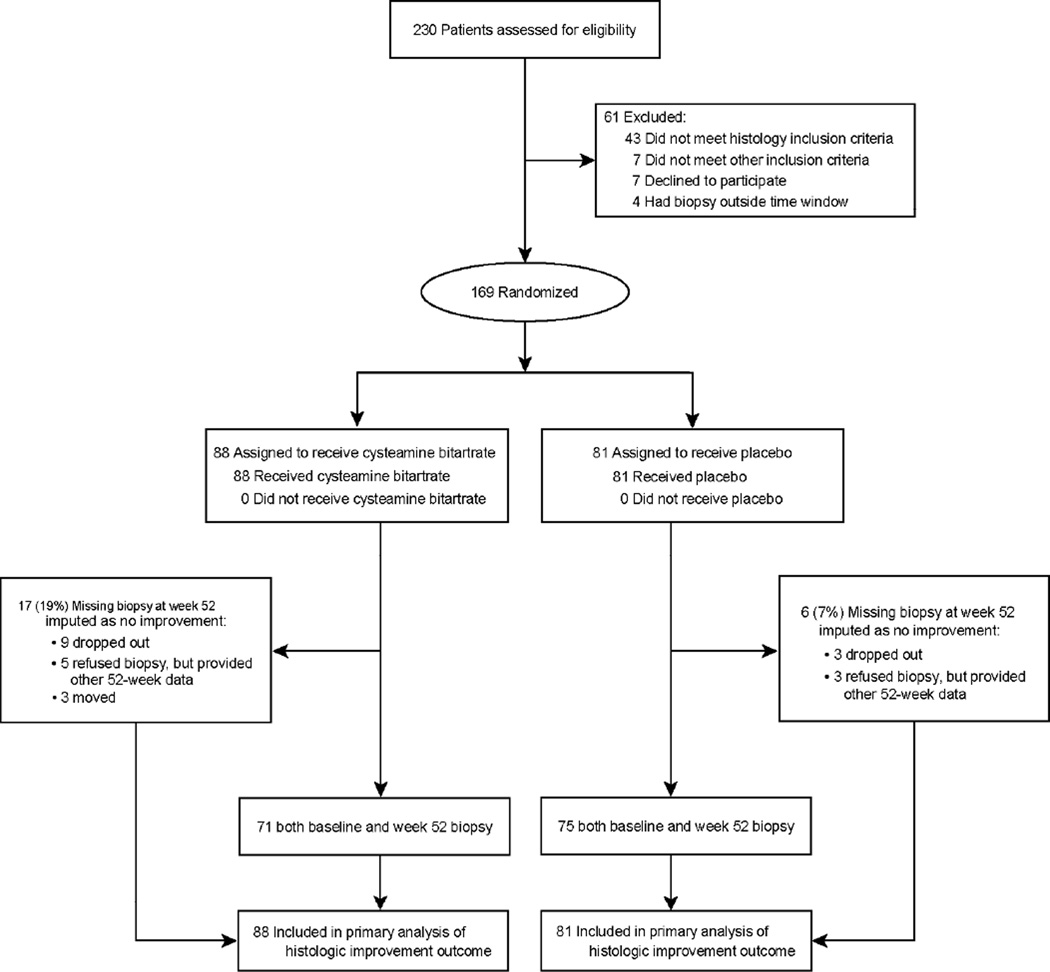

A total of 230 children with suspected NAFLD were screened and 169 randomized into the CyNCh trial (Figure 1). The most common reason for ineligibility was not meeting the histologic inclusion criteria (70%, 43/61). Of the total, 88 children were assigned to receive CBDR and 81 to receive placebo. The baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 13.7 ± 2.7 years, 70% of participants were male, and 73% were Hispanic. The median (interquartile range) ALT was 87 (62–151) U/L and AST was 52 (39–79) U/L. There were no significant differences between groups, except the proportion of children with diabetes, which was lower in the CBDR group compared to placebo (1% vs. 9%, p=0.03). The overall mean NAS was 4.7 and ranged from 2 to 8. Central review of baseline liver histology indicated that 136 of the 169 participants (80%) had a NAFLD activity score ≥ 4 at study entry. Advanced fibrosis was present in 18% of participants. The liver histology features and severity were similar between treatment groups; however, lobular inflammation was slightly greater in the CBDR group compared to the placebo group (mean score of 1.8 vs. 1.6, p=0.02).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram of CyNCh Trial Participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| CBDR (N=88) |

Placebo (N=81) |

Total (N=169) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight stratum | |||

| ≤65 kg | 24 (27%) | 23 (28%) | 47 (28%) |

| >65–80 kg | 14 (16%) | 10 (12%) | 24 (14%) |

| >80 kg | 50 (57%) | 48 (59%) | 98 (58%) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 13.8 (2.9) | 13.6 (2.5) | 13.7 (2.7) |

| Male | 63 (72%) | 56 (69%) | 119 (70%) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 (6%) | 6 (7%) | 11 (7%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Black or African-American | 3 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 6 (4%) |

| White | 56 (64%) | 46 (57%) | 102 (60%) |

| More than one race | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) |

| Refusal/not stated* | 21 (24%) | 23 (28%) | 44 (26%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 66 (75%) | 58 (72%) | 124 (73%) |

| Self-Reported Pediatric QOL† | |||

| Physical health | 81 (15) | 82 (19) | 81 (17) |

| Psychosocial health | 75 (16) | 77 (16) | 76 (16) |

| Parent/guardian-Reported Pediatric QOL† | |||

| Physical health | 68 (21) | 69 (24) | 68 (23) |

| Psychosocial health | 67 (19) | 68 (18) | 68 (19) |

| Liver enzymes | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 93 (67–175) | 80 (61–120) | 87 (62–151) |

| Mean (SD) | 140 (118) | 104 (76) | 123 (101) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 55 (40–91) | 49 (38–69) | 52 (39–79) |

| Mean (SD) | 82 (71) | 59 (38) | 71 (59) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 224 (116) | 214 (101) | 220 (109) |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | 50 (33) | 44 (29) | 47 (31) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.54 (0.34) | 0.50 (0.26) | 0.52 (0.30) |

| Lipids | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 165 (40) | 163 (37) | 164 (38) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 39 (9) | 41 (9) | 40 (9) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 95 (32) | 92 (31) | 94 (31) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 126 (40) | 122 (37) | 124 (39) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 160 (81) | 157 (77) | 158 (79) |

| Metabolic factors | |||

| Weight (kg) | 85 (26) | 84 (25) | 85 (25) |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 33 (7) | 32 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Body-mass index z-score | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.2 (0.4) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 104 (15) | 103 (15) | 103 (15) |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dL) | 87 (10) | 88 (14) | 88 (12) |

| Insulin (µU/mL)‡ | 35 (31) | 38 (34) | 36 (32) |

| HOMA-IR (glucose [mmol/L] x insulin [µU/mL]/22.5)§ |

7.7 (7.5) | 8.4 (7.7) | 8.0 (7.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 120 (11) | 120 (12) | 120 (11) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 68 (8) | 67 (10) | 67 (9) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes¶ | 1 (1%) | 7 (9%) | 8 (5%) |

| Hypertension | 9 (10%) | 6 (7%) | 15 (9%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 13 (15%) | 12 (15%) | 25 (15%) |

| Liver histology findings | |||

| NAFLD activity score∥ | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.4) |

| Steatosis score | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| Lobular inflammation score¶ | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) |

| Hepatocellular ballooning score | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.7) |

| Portal inflammation score** | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Fibrosis stage | |||

| 0 - None | 24 (27%) | 25 (31%) | 49 (29%) |

| 1a - Mild, zone 3 perisinusoidal | 9 (10%) | 7 (9%) | 16 (9%) |

| 1b - Moderate, zone 3 perisinusoidal | 6 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 11 (7%) |

| 1c - Portal/periportal only | 20 (23%) | 20 (25%) | 40 (24%) |

| 2 - Zone 3 and periportal, any combination | 9 (10%) | 13 (16%) | 22 (13%) |

| 3 - Bridging | 19 (22%) | 11 (14%) | 30 (18%) |

| 4 - Cirrhosis | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Fibrosis stage†† | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.1) |

| Steatohepatitis | |||

| No | 25 (28%) | 19 (23%) | 44 (26%) |

| Borderline Zone 3 pattern | 16 (18%) | 10 (12%) | 26 (15%) |

| Borderline Zone 1 pattern | 23 (26%) | 29 (36%) | 52 (31%) |

| Definite | 24 (27%) | 23 (28%) | 47 (28%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD), unless otherwise noted.

Patients who refused or did not report race were all of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (N=44).

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (version 4.0), Child and Parent Reports for Children (ages 8–12) and Teens (ages 13–18). Scores are transformed on a scale from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better quality of life.

One outlier with insulin of 718.7 umol/mL was excluded.

HOMA-IR=homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance.

The only statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics by treatment group were diabetes status (P=0.03) and lobular inflammation score (P=0.02).

NAFLD activity score was assessed on a scale of 0–8, with higher scores showing more severe disease (the components of this measure are steatosis [assessed on a scale of 0–3], lobular inflammation [assessed on a scale of 0–3], and hepatocellular ballooning [assessed on a scale of 0–2]).

Portal inflammation was assessed on a scale of 0–2, with higher scores showing more severe inflammation.

Mean fibrosis stage assessed on a scale of 0–4, with higher scores showing more severe fibrosis.

Follow-up and Adherence

All children initiated their assigned treatment. Overall, participants took 69±26% of the prescribed study medication. Notably, adherence to study drug was significantly lower in the CBDR group than in the placebo group (63±29% vs 76±22%, p = 0.002). In the CBDR group, 14% (12/88) of children discontinued participation prior to week 52, compared to 4% (3/81) in the placebo group (p=0.03). When restricted to those children who completed the study, there was still significantly lower adherence to study drug in the CBDR group than in the placebo group (70±23% vs 78±20%, p =0.02). Follow-up liver biopsies were obtained in 81% (71/88) of children taking CBDR and 93% (75/81) of children taking placebo (p=0.03). Liver biopsy complications were uncommon, generally mild in severity and self-limited in course. There were no cases of clinically apparent bleeding or infection. Pain was reported in five of 146 (3%) children following the end-of-treatment liver biopsy. In four children, the post-biopsy pain resolved within 24 hours. The remaining child was hospitalized after liver biopsy for pain that resolved with supportive care.

Primary Outcome

There was no statistically significant difference between the CBDR group and the placebo group in the proportion of children who met the primary outcome of 52-week histologic improvement, defined as a decrease in NAS of 2 points or more and no worsening of fibrosis; 28% (25/88) of children assigned to CBDR and 22% (18/81) of children assigned to placebo improved (relative risk =1.3, 95% CI 0.8 – 2.1, p=0.34) (Table 2). For children who had complete follow-up including liver histology at week 52, the primary outcome was achieved in 35% (25/71) in the CBDR group versus 24% (18/75) in the placebo group (RR =1.4, 95% CI 0.9 – 2.4, p = 0.16).

Table 2.

Changes in histological features of the liver after 52 weeks of treatment

| CBDR | Placebo | Relative risk or differences in mean changes from baseline* (95% CI) CBDR vs. placebo |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic Improvement - Primary Outcome† | ||||

| Number of patients | 88 | 81 | ||

| Patients with improvement | 25 (28%) | 18 (22%) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) | 0.34 |

| Histologic Improvement – Completed follow-up | ||||

| Number of patients | 71 | 75 | ||

| Patients with improvement | 25 (35%) | 18 (24%) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.16 |

| Changes from baseline in histological features‡ | ||||

| NAFLD activity score | ||||

| Change in score | −0.8 ± 1.8 | −0.8 ± 1.8 | 0.0 (−0.6, 0.5) | 0.90 |

| Steatosis | ||||

| Patients with improvement | 26 (30%) | 33 (41%) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) | 0.15 |

| Change in score | −0.3 ± 0.9 | −0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.4) | 0.59 |

| Lobular inflammation | 32 (36%) | 17 (21%) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | 0.03 |

| Patients with improvement | −0.4 ± 0.8 | −0.1 ± 0.8 | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | 0.06 |

| Change in score | ||||

| Hepatocellular ballooning | ||||

| Patients with improvement | 17 (19%) | 21 (26%) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.29 |

| Change in score | −0.1 ± 0.7 | −0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.15 |

| Portal inflammation§ | ||||

| Patients with improvement | 18 (20%) | 14 (17%) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.3) | 0.57 |

| Change in score | −0.1 ± 0.6 | −0.1 ± 0.6 | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.76 |

| Fibrosis¶ | ||||

| Patients with improvement | 25 (28%) | 23 (28%) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.98 |

| Change in score | −0.3 ± 0.9 | −0.1 ± 1.0 | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.1) | 0.24 |

| Resolution of NASH∥ | 4 (17%) | 2 (9%) | 2.7 (0.4, 18.3) | 0.29 |

Data are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Relative risks and p-values were calculated with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests, stratified by clinic and weight group, for binary outcomes; p-values and mean changes from baseline were calculated using ANCOVA, regressing change from baseline to 52 weeks on treatment group and baseline value of the outcome, for outcome scores.

The primary outcome was histologic improvement, defined as a decrease of 2 or more points in the total nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score (NAS) and no worsening in the fibrosis stage; 17 patients in the cysteamine bitartrate group and six in the placebo group had missing histological data at week 52, and the results for these patients were imputed as a lack of improvement; NAFLD activity score was assessed on a scale of 0–8, with higher scores showing more severe disease (the components of this measure are steatosis [assessed on a scale of 0–3], lobular inflammation [assessed on a scale of 0–3], and hepatocellular ballooning [assessed on a scale of 0–2]).

Improvement in histological features was based on ITT, where missing biopsies were imputed as a lack of improvement. Change in histological score was based on complete case analysis, where missing biopsies were excluded.

Portal inflammation was assessed on a scale of 0–2, with higher scores showing more severe inflammation.

Fibrosis was assessed on a scale of 0–4, with higher scores showing more severe fibrosis.

Resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was defined as a diagnosis of definite nonalcoholic steatohepatitis at baseline and a diagnosis of not NAFLD or NAFLD only on week 52 biopsy; 24 patients in the CBDR group and 23 patients in the placebo group had definite NASH at baseline.

Secondary Outcomes

Weight increased over the course of 52 weeks. The mean weight gain was 7.1 kg with no significant difference between treatment groups (p=0.25). Overall for participants in CyNCh, BMI z-score was stable in 49%, decreased/improved in 29%, and increased/worsened in 23%. There was no significant difference in the change in glucose, lipids, or blood pressure by treatment group.

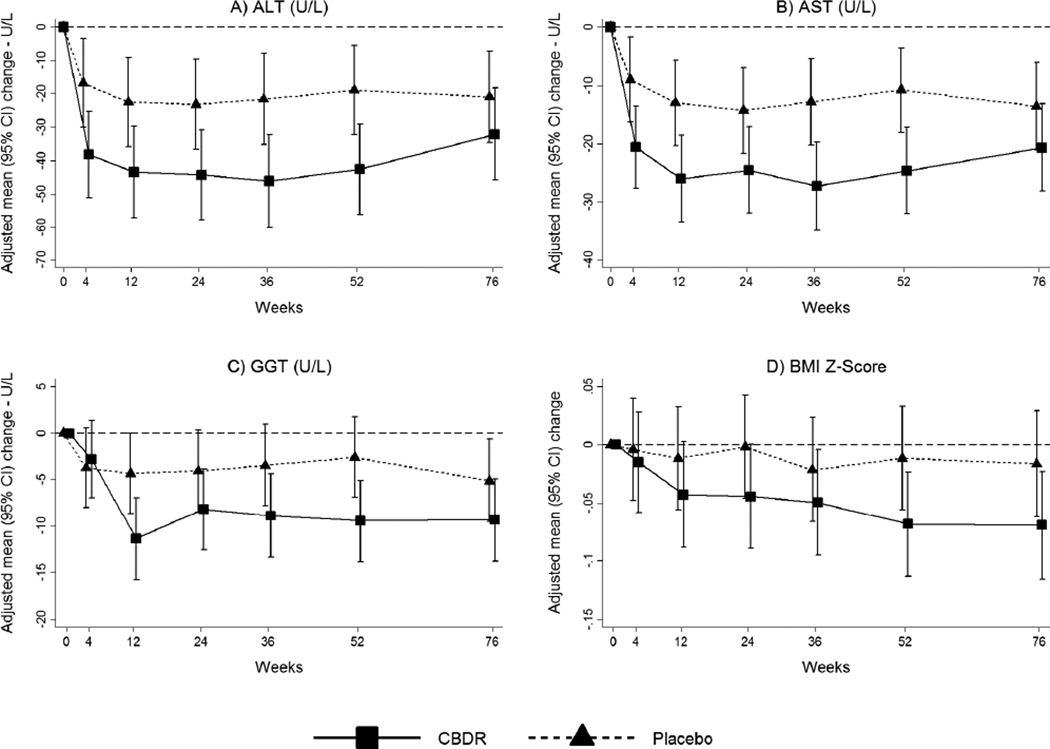

As shown in Table 3, serum liver chemistry values improved significantly with CBDR treatment. Most notably the mean± standard deviation change in ALT from baseline in the CBDR group was −53 ±88 U/L, compared to −8 ±77 U/L in the placebo group (p=0.02) (Table 3). Similarly, the mean change in AST from baseline was −31±52 U/L in the CBDR group compared to −4±36 U/L in the placebo group (p=0.008). In addition the change in GGT was significantly greater with CBDR compared to placebo (-10±23 U/L vs −1±16 U/L; p=0.02). The changes in liver enzyme values occurred within 4 to 12 weeks of starting therapy and remained stable throughout the treatment period (Figure 2). The between group differences at 24 weeks post-treatment were smaller and not significant (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in liver enzymes, serum biochemical tests, metabolic factors, and quality of life from baseline to 52 weeks

| Change from baseline to 52 weeks (mean[SD]) |

Adjusted differences in mean changes from baseline (CBDR vs. placebo) (95% CI) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBDR (N=75) |

Placebo (N=77) |

|||

| Liver enzymes | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | −53 (88) | −8 (77) | −24 (−44, −4) | 0.02 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | −31 (52) | −4 (36) | −15 (−26, −4) | 0.008 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | −31 (70) | −19 (54) | −9 (−28, 10) | 0.37 |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | −10 (23) | −1 (16) | −7 (−13, −1) | 0.02 |

| Lipids | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | −11 (23) | −4 (22) | −6 (−13, 0) | 0.07 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.0 (6.2) | −0.4 (7.6) | −0.6 (−2.7, 1.6) | 0.61 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −10 (19) | −3 (20) | −5 (−11, 1) | 0.09 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −11 (22) | −4 (19) | −6 (−13, 0) | 0.06 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | −7 (60) | 0 (68) | −5 (−25, 14) | 0.59 |

| Metabolic factors | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 6.3 (9.3) | 7.8 (6.6) | −1.5 (−4.1, 1.1) | 0.25 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 0.8 (2.8) | 1.1 (2.2) | −0.3 (−1.1, 0.5) | 0.42 |

| Body-mass index z-score | −0.1 (0.3) | 0 (0.2) | −0.1 (−0.1, 0.0) | 0.11 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 2.5 (7.7) | 2.3 (7.5) | 0.2 (−2.3, 2.6) | 0.89 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dL) | 1 (12) | 5 (27) | −4 (−11, 3) | 0.24 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | 6 (36) | 10 (40) | −6 (−18, 6) | 0.34 |

| HOMA-IR (glucose [mmol/L] x insulin [pmol/L]/22.5) |

1.4 (9.2) | 3.6 (12.5) | −2.6 (−6.2, 1.0) | 0.15 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 3 (12) | 2 (12) | 1 (−3, 4) | 0.71 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | −1 (9) | 1 (9) | −1 (−4, 1) | 0.31 |

| Self-Reported Pediatric QOL | ||||

| Physical health | 4 (17) | 5 (16) | −1 (−5, 3) | 0.77 |

| Psychosocial health | 4 (15) | 5 (14) | −1 (−5, 3) | 0.64 |

|

Parent/guardian-Reported Pediatric QOL |

||||

| Physical health | 4 (27) | 5 (24) | −2 (−9, 5) | 0.58 |

| Psychosocial health | 5 (18) | 6 (24) | −1 (−6, 5) | 0.85 |

Data are mean (SD). P-values and differences in means changes from baseline were calculated using ANCOVA models, regressing change from baseline to 52 weeks on treatment group and baseline value of the outcome.

Number of patients in the CBDR group ranged from 70 to 75 and number of patients in the placebo group ranged from 73 to 77 due to missing values.

Figure 2. Changes from baseline in liver enzymes and body mass index z-score according to treatment group.

Mean values of changes from baseline during treatment with CBDR (88 patients) or Placebo (81 patients) for up to 52 weeks followed by a 24-week off-treatment period are shown. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. P-values for the overall treatment effect of change over time on treatment (weeks 4–52) were derived from GEE linear regression, modeling change as a function of treatment group, visit code indicators, baseline value of the outcome, and treatment group by visit code interaction terms; p-values for the treatment effect at each visit were derived from linear regression, modeling change as a function of treatment group and the baseline value of the outcome. (A) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations decreased in both the CBDR and placebo groups 4 weeks after initiating treatment and were sustained during the remaining 48-week treatment period but with a significantly greater decrease in patients treated with CBDR (p=0.07 for visits at weeks 4 through 52; p=0.02, 0.01, 0.02, 0.02, 0.02 at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36 and 52 respectively). ALT concentrations in the CBDR group were similar to placebo 24 weeks after treatment discontinuation (p=0.49). (B) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) had a similar pattern (p=0.02 for visits at weeks 4 through 52; p=0.06, 0.006, 0.04, 0.007, 0.008, 0.28 at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, 52 and 76, respectively). (C) γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) had a similar pattern with significantly greater decrease in GGT starting at 12 weeks (p=0.01 for visits at weeks 4 through 52; p=0.98, 0.03, 0.03, 0.11, 0.02, 0.24 at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, 52 and 76, respectively). (D) Body mass index z-score did not have a significantly greater decrease for CBDR compared to placebo at any visit (p=0.54 for visits at weeks 4 through 52; p=0.48, 0.16, 0.11, 0.33, 0.11, 0.32 at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, 52 and 76, respectively).

The number of patients represented in the figures range from 73–88 in the CBDR group and 74–81 in the placebo group.

The changes in the individual histologic features by treatment group are shown in Table 2. Steatosis was present in all children at baseline. There was no significant difference in improvement in steatosis by treatment group. Lobular inflammation was also present in all children. There was a significant difference in improvement in lobular inflammation by treatment group (CBDR 36% 32/88 vs placebo 21% 17/81; RR 1.8 (1.1, 2.9), p=0.03). Ballooning was present in less than half of children at baseline (47% 41/88 in the CBDR group and 42% 34/81 in the placebo group). There was not a significant difference in improvement in ballooning between treatment groups. At baseline, portal inflammation was present in 90% (79/88) of children in the CBDR group and 91% (74/81) of children in the placebo group. There was not a significant difference in the degree of change in portal inflammation between treatment groups. Fibrosis was present at baseline in 73% (64/88) of children in the CBDR group and 69% (56/81) of the placebo group. There was not a significant difference in improvement in fibrosis by treatment group.

Subgroup Analyses

Because age, sex, and weight have repeatedly been shown to influence prevalence and severity of NAFLD in children, these were each examined in subgroup analyses 9. When children were dichotomized as < 13 years at baseline or ≥ 13 years, the overall significance for a treatment by age interaction was p = 0.05. For children < 13 years, there was histologic improvement in 43% (16/37) of children receiving CBDR versus 21% (8/39) of children receiving placebo (RR 2.3; 95% CI 1.0–5.2; p=0.04). In contrast, there was no significant difference in response in children ≥ 13 years (RR 0.9; 95% CI 0.4–2.1; p=0.86). In addition, there was no significant difference in histologic response by sex (interaction p = 0.58) (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, there was a significant difference in response by weight categories (interaction p=0.01) (Table 4). Among children with baseline weight ≤ 65 kg, there was histologic improvement in 50% receiving CBDR, compared to 13% receiving placebo (RR 4.0, 95%CI 1.3–12.3, p=0.005). There was no difference in histologic improvement for children who weighed more than 65 kg at baseline which was 20% of children receiving CBDR versus 26% receiving placebo (RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.4 – 1.4, p=0.39). Although the prescribed number of 75 mg capsules twice per day increased for the 3 weight strata (<=65 kg, >65–80 kg, >80 kg) from 4 to 6, children with baseline weight <=65 kg received a significantly (p <0.0001) higher dose of study drug on a milligram per kilogram body weight basis (11.3 ± 1.6 mg/kg; range 9.2–15.9 mg/kg) than children with baseline weight >65 kg (9.3 ± 1.4 mg/kg; range 6.0–11.6 mg/kg) (Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, the RR for histologic improvement significantly (interaction p=0.01) increased with increasing dose (mg/kg), with an RR=3.2 (95% CI 0.8 – 12.2, p=0.07) for children in the highest quartile of dose (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4.

Changes in histological features of the liver after 52 weeks of treatment in patients with weight ≤65 kg vs. >65 kg

| Patients ≤65 kg at baseline |

Patients >65 kg at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBDR | Placebo | RR or differences in mean changes* (95% CI) |

P* | CBDR | Placebo | RR or differences in mean changes* (95% CI) |

P* | Interaction P <65kg vs. >65 kg† |

|

| Primary Outcome‡ | |||||||||

| Number of patients | 24 | 23 | 64 | 58 | |||||

| Patients with improvement | 12 (50%) | 3 (13%) | 4.0 (1.3, 12.3) | 0.005 | 13 (20%) | 15 (26%) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Completed follow-up | |||||||||

| Number of patients | 21 | 21 | 50 | 54 | |||||

| Patients with improvement | 12 (57%) | 3 (14%) | 4.1 (1.3, 12.3) | 0.005 | 13 (26%) | 15 (28%) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.70 | 0.01 |

|

Adherent to prescribed dose of study medication§ |

|||||||||

| Number of patients | 9 | 15 | 20 | 25 | |||||

| Patients with improvement | 5 (56%) | 2 (13%) | 3.8 (0.8, 18.9) | 0.06 | 5 (25%) | 5 (20%) | 1.3 (0.4, 4.1) | 0.67 | 0.15 |

|

Changes from baseline in histological features |

|||||||||

| NAFLD activity score | |||||||||

| Change in score | −1.7 ± 1.6 | −0.8 ± 1.3 | −0.6 (−1.5, 0.3) | 0.21 | −0.4 ± 1.8 | −0.8 ± 2.0 | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.8) | 0.64 | 0.30 |

| Steatosis | |||||||||

| Patients with improvement | 12 (50%) | 11 (48%) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) | 0.85 | 14 (22%) | 22 (38%) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Change in score | −0.7 ± 1.1 | −0.6 ± 0.9 | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.4) | 0.61 | −0.1 ± 0.8 | −0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.2 (−0.1, 0.5) | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| Lobular inflammation | |||||||||

| Patients with improvement | 13 (54%) | 5 (22%) | 2.6 (1.1, 6.0) | 0.02 | 19 (30%) | 12 (21%) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.7) | 0.30 | 0.21 |

| Change in score | −0.7 ± 0.8 | −0.1 ± 0.7 | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.2) | 0.36 | −0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 0.8 | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | 0.11 | 0.99 |

| Hepatocellular ballooning | |||||||||

| Patients with improvement | 8 (33%) | 1 (4%) | 8.3 (1.0, 71.3) | 0.01 | 9 (14%) | 20 (34%) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Change in score | −0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.3) | 0.82 | 0.0 ± 0.7 | −0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.2 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| Portal inflammation¶ | |||||||||

| Patients with improvement | 8 (33%) | 5 (22%) | 1.5 (0.6, 3.9) | 0.42 | 10 (16%) | 9 (16%) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.4) | 0.92 | 0.49 |

| Change in score | −0.2 ± 0.7 | −0.2 ± 0.7 | −0.1 (−0.5, 0.3) | 0.60 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.94 | 0.72 |

| Fibrosis∥ | |||||||||

| Patients with improvement | 10 (42%) | 10 (43%) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.8) | 0.98 | 15 (23%) | 13 (22%) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.97 | 0.86 |

| Change in score | −0.4 ± 1.2 | −0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.6) | 0.92 | −0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.0 ± 0.9 | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.1) | 0.11 | 0.42 |

|

Changes from baseline in liver enzymes and BMI z-score |

|||||||||

| Number of patients** | 21 | 23 | 53 | 54 | |||||

| Change in ALT (U/L) | −82 ± 119 | −23 ± 52 | −14 (−50, 23) | 0.46 | −41 ± 71 | −2 ± 85 | −26 (−49, −4) | 0.02 | 0.83 |

| Change in AST (U/L) | −42 ± 61 | −11 ± 23 | −9 (−29, 11) | 0.37 | −27 ± 48 | 0 ± 39 | −17 (−30, −5) | 0.007 | 0.54 |

| Change in BMI z-score | −0.2 ± 0.2 | −0.1 ± 0.2 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.0) | 0.03 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) | 0.60 | 0.14 |

Data are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Relative risks and p-values were calculated with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test, stratified by clinic and weight group, for binary outcomes; p-values and mean changes from baseline were calculated using ANCOVA, regressing change from baseline to 52 weeks on treatment group and baseline value of the outcome, for outcome scores.

Interaction p-values calculated using logistic regression models for binary outcomes and linear regression models for continuous outcomes, regressing treatment group, binary weight group, and the treatment group by weight group interaction term on the outcome. Models for changes in scores including terms for the baseline value of the outcome.

The primary outcome was histologic improvement, defined as a decrease of 2 or more points in the total nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score (NAS) and no worsening in the fibrosis stage; 17 patients in the CBDR group and six in the placebo group had missing histological data at week 52, and the results for these patients were imputed as a lack of improvement; NAFLD activity score was assessed on a scale of 0–8, with higher scores showing more severe disease (the components of this measure are steatosis [assessed on a scale of 0–3], lobular inflammation [assessed on a scale of 0–3], and hepatocellular ballooning [assessed on a scale of 0–2]).

Adherence defined as >80% of study drug that should have been taken if perfectly adherent to prescription, based on weight group and number of days in study, was reported taken, based on counts of returned study drug capsules.

Portal inflammation was assessed on a scale of 0–2, with higher scores showing more severe inflammation.

Fibrosis was assessed on a scale of 0–4, with higher scores showing more severe fibrosis.

The number of patients ≤65 kg with change in BMI z-score available was 22 in the CBDR group and 23 in the placebo group. The number of patients >65 kg with change in BMI z-score available was 52 in the CBDR group and was 53 in the placebo group.

Adverse Events

Serious adverse events were uncommon and did not differ by treatment group; CBDR, n = 5/88, 6%; and placebo, n = 4/81, 5%; p = 1.0 (Table 5). Total adverse events were common overall during the 52 weeks of treatment and were not different by treatment group; 70% of children in the CBDR group and 67% of children in the placebo group reported at least 1 adverse event. Among those children who reported an adverse event, there was an average of 3 adverse events per person. There were also no significant differences between treatment groups with respect to adverse events by body system. For example, the most common body system for adverse events was gastrointestinal. There were 34 children (39%) in the CBDR group who experienced a total of 48 gastrointestinal events compared to 33 children (41%) in the placebo group who reported a total of 52 gastrointestinal events (p=0.88). During the one year of treatment, there were 9 children (9/169 = 5%) who had new symptoms of anxiety and/or depression that warranted referral for evaluation and treatment. However, no single symptom or adverse event was significantly more frequent in the CBDR group than the placebo group.

Table 5.

Adverse events by body system

| All Adverse Events |

Serious Adverse Events* |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBDR (N=88) |

Placebo (N=81) |

CBDR (N=88) |

Placebo (N=81) |

|||||||

| Body System/ Category† |

No. of events |

No. of patients |

No. of events |

No. of patients |

P‡ | No. of events |

No. of patients |

No. of events |

No. of patients |

P‡ |

| Auditory | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Allergy | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Ocular/Visual | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hepatobiliary/ Pancreas |

3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Infection | 12 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.48 |

| Constitutional Symptoms |

4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.68 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Psychiatric | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1.00 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Cardiovascular | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Dermatological | 18 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 0.82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Endocrine | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1.00 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Gastrointestinal | 48 | 34 | 52 | 33 | 0.88 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Lymphatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Musculoskeletal/ Soft Tissue |

15 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.48 |

| Neurology | 14 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary/Upper Respiratory |

24 | 16 | 31 | 18 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Renal/ Genitourinary |

3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Sexual | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Other | 10 | 9 | 16 | 13 | 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Total§ | 179 | 62 | 174 | 54 | 0.62 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1.00 |

Serious Adverse Event defined as an event meeting one or more of the following criteria: severity grade 4 (life threatening or disabling) or 5 (death); inpatient hospitalization or prolonged existing hospitalization; persistent or significant incapacity or substantial disruption of ability to conduct normal life functions; jeopardized patient and required medical or surgical intervention to prevent a serious event; or congenital anomaly or birth defect.

Derived from adverse events reported on the Adverse Event Report (AE) forms that were completed by the principal investigator. Events reports at the 76-week visit (post-treatment phase) were removed.

P-values for the differences in distributions of adverse events, categorized by body system, were assessed for CBDR vs. placebo using Fisher’s exact tests.

Total number of reports is the sum of the events across all body systems. Multiple body systems may be reported on each form and patients may have multiple Adverse Event Report forms.

Total number of patients is the number of unique patients with one or more Adverse Event Report forms. The total is less than the sum across body system because multiple body systems may be reported on each form.

DISCUSSION

We performed a large, multi-center randomized controlled clinical trial of cysteamine bitartrate delayed release as a treatment for NAFLD in children with liver histology as a primary endpoint. Treatment with CBDR for 52 weeks was safe, but did not improve liver histology as assessed by the composite NAS in children with NAFLD compared to placebo. Of the NAS components, there was a significantly greater improvement with CBDR for lobular inflammation but not steatosis or hepatocyte ballooning. There was however, a rapid, marked, and sustained improvement in serum aminotransferase levels in children given CBDR compared to placebo.

CyNCh was the first clinical trial in children with NAFLD specifically designed to assess changes in liver histology as the primary outcome. CyNCh was designed with an efficacy target such that ≥ 50% of children taking CBDR would have needed to have a decrease in NAS ≥ 2 points in order for the study to have shown a significant difference compared to placebo. One question raised is how large an effect size should be expected for a medication to treat NAFLD in children. Over 96 weeks in the Treatment of NAFLD in Children (TONIC) study, using the same measure of decrease in NAS of ≥ 2 points and no worsening of fibrosis as done in CyNCh, there was histologic improvement in 42% (24/57) of children taking metformin, 34% (20/58) of children taking vitamin E, and 21% (12/58) of children taking placebo 30. At this point in time, it is unknown how to extrapolate the effect of any given medication taken for 1 year versus 2 years. However, it is notable that the rate of response in the placebo groups was similar. Moreover, the efficacy target although ambitious was reasonable based upon the available evidence.

There were factors regarding liver histology at baseline and at end of treatment which may have influenced the primary outcome. Because of differences in individual Pathology Committee member versus central pathology assessment by the committee, 20% of children enrolled in CyNCh had a baseline NAS of 2 or 3. Moreover, study results may have been influenced by the lower biopsy rate at the end of treatment in the CBDR group. We predicted that at least 90% of children in CyNCh would undergo a protocol liver biopsy at the end of treatment. However, that was not achieved in the CBDR group (81%). The reason for this is unclear as there were no significant differences in adverse events reported between groups. However, it is possible that some children taking CBDR experienced unreported symptoms that led to their discontinuation of medication. This would be consistent with the lower rate of overall adherence with medication in the CBDR group. Alternatively, there may have been unmeasured or random factors responsible for the differences observed. Regardless of the actual reason(s), the differences in adherence and completion had the potential to adversely influence the study results. A sensitivity analysis was performed that used multiple imputation assuming missing biopsies were missing at random and there was a higher relative improvement ratio for CBDR of 1.5, but this was still not significant.

Interestingly, treatment with CBDR was associated with substantial improvement in serum aminotransferase activity. The changes observed over 52 weeks were similar to those seen in a prior 6 month pilot study17. Remarkably, the rate of change in ALT in CyNCh was rapid, such that most of the improvement in ALT was seen by 4 weeks. The clinical relevance of improvement in ALT in NASH treatment trials has been controversial. The only prior study with longitudinal data for both ALT and liver histology in children was TONIC30. Notably, in TONIC, the change in ALT had an AUROC of 0.79 for predicting histologic improvement in children over 96 weeks 31. In addition, with every 10 U/L decrease in ALT levels over 96 weeks, children in TONIC had 28% greater odds of histologic improvement. Of additional importance, in CyNCh, there were also significant improvements in AST and GGT associated with CBDR treatment. However, relying on these changes in serum aminotransferase levels as a surrogate for histological improvement would have led to a different conclusion regarding the effect of CBDR on NAFLD in children. Thus, additional analyses will be required to better understand the relationships between changes in liver histology and changes in serum aminotransferase activity in children with NAFLD.

NAFLD is a heterogeneous disorder with at least 3 histologic patterns observed in children: those with steatosis and relatively mild features overall, those with histologic alterations that are predominantly focused in zone 1, and those with histologic features that are predominantly focused in zone 3 as is more typical in adults with NAFLD 2. These differences in histology are in part related to age and sex, with major histologic differences noted for school age children versus adolescents, and for boys versus girls. Therefore, we performed post-hoc subgroup analyses based upon age and sex. We also evaluated response by weight groups, as these were used for randomization and determination of dose. In these analyses, we observed that there was evidence for treatment group differences in histologic improvement associated with CBDR for children < 13 years of age and for children who were ≤ 65 kg at baseline.

Evaluating response by age subgroups is commonly recommended for pediatric studies, especially those with a large age range such as we had in CyNCh 32. Younger children have biological differences compared to adolescents including that they are more likely to be pre-pubertal or in early stages of puberty, and they tend to have fewer co-morbidities. With respect to NAFLD, they may also have had disease for a shorter duration of time. In addition, there are psychosocial and developmental differences that may influence clinical trial results by age. For example, younger children may be more adherent to medication due in part to greater parental control and participation. It is also biologically plausible that weight is a relevant factor for the response to treatment in pediatric NAFLD. Obesity is one of the most important risk factors for NAFLD in children33. However, there is a very large range in weight, BMI, and BMI z-scores in those children with NAFLD, from those who are mildly overweight to those who are severely obese 4. Children in the highest weight group, who comprised 58% of the participants, were asked to take 50% more pills per day than children in the lowest weight group. Thus, adherence may have been one confounding factor. Secondly, despite taking more pills per day, children who weighed > 65 kg at baseline received a lower relative dose on a mg/kg basis and thus may have been under-dosed. Moreover, greater severity of obesity is also associated with additional co-morbidities than may make it harder to treat NAFLD in these children 8, 34, 35. Because lighter-weight children are also more likely to be in the younger age group it is difficult to separate these issues from one another. Clinical trials have the potential to uncover important disease sub-phenotypes; different subgroup responses may represent different underlying pathophysiology. However, to make best use of such information will require targeted studies designed to address such differences. A medication that is effective only in a subset of patients may be a useful therapy if specific parameters are met: 1. that the effect in those who respond is large enough to be clinically relevant, 2. that children most likely to respond can be identified prior to treatment, and 3. that a response or non-response can be detected in a reasonable time frame. It is premature to base patient care decisions upon these subgroup analyses because there is the potential for false discovery, however they raise important questions that merit further focused research.

There were several lessons learned in CyNCh that are important to future treatment studies in pediatric NAFLD. First, children with NAFLD are a complex patient group that experience a high rate of symptoms and health events. In order to optimize their participation in clinical trials, consideration of the global needs of each individual child is required. Second, CyNCh demonstrated both the challenge and importance of assuring adherence to study medication and of obtaining complete follow-up. Third, the selection of dose and the achievement of that dose were complicated by the evolution of different formulations of cysteamine bitartrate, the wide range of body weight among participants, and the potential for substantial weight gain in this population. The target dose of 9–12 mg/kg per day was achieved for all children with baseline weight ≤ 65 kg, but it was not achieved for all children with baseline weight > 65 kg. Moreover, the mean weight gain during the treatment period was 7 kg and the dose of CBDR was not adjusted for changes in weight during the course of the study. A formal dose ranging study may be required to further address these issues. Finally, this study demonstrated that liver biopsy is an acceptable and important outcome measure for clinical trials of pediatric NAFLD as it was safe, well tolerated, and feasible. However, challenges remain in the interpretation of histologic response, especially for children with NAFLD.

In summary, 52 weeks of treatment with CBDR was safe but did not result in a significant increase in histologic improvement of the liver as assessed by the composite NAFLD Activity Score in children with NAFLD compared to placebo. In contrast, there were significant, substantial, rapid and sustained improvements in serum aminotransferase activity with CBDR treatment. Subgroup analyses suggested the potential for benefit in some children, however, these findings will need to be verified in future trials designed to address the role of age, weight, and dose. Lessons learned in CyNCh may guide these and other future clinical trials for pediatric NAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NASH CRN expresses its gratitude to Averell Sherker for his assistance in coordinating communications among the NIDDK, the industry sponsor, and the NASH CRN Steering Committee; and to Jay Hoofnagle for his guidance with trial design and with data analysis and interpretation.

Grant support: The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713). Additional support is received from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grants UL1TR000077, UL1TR000150, UL1TR000424, UL1TR000006, UL1TR000448, UL1TR000040, UL1TR000100, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000423, UL1TR000454). This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. This study was also funded in part by Raptor Pharmaceuticals via a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with the NIDDK.

Disclosures: Schwimmer, Lavine, Wilson, Vos, Molleston, Whitington, Murray, Brunt, Kleiner, Van Natta, Clark, Tonascia and Doo report no conflicts of interest. Neuschwander-Tetri reports consulting for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Conatus, Enanta, Galmed, Janssen, Nimbus, Novartis, Pfizer, Receptos, Zafgen. Xanthakos reports grant support from Raptor. Kohli reports consulting for Alexion and grant support from Raptor. Barlow reports grant support from Zafgen. Karpen reports consulting for Intercept. Rosenthal reports consulting for Gilead, Abbvie, Retrophin, and grant support from Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Roche/Genentech, Infacare, Abbvie. Jain reports consulting for Alexion.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- NAS

NAFLD Activity Score

- CBDR

Cysteamine Bitartrate Delayed Release

- NASH

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

- DCC

Data Coordinating Center

- DSMB

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- NDSR

Nutrition Data System for Research

Appendix 1. List of NASH CRN participating Centers

Clinical Centers

Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago, IL (Peter Whitington, MD)

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Stavra Xanthakos, MD)

Columbia University, New York, NY (Joel Lavine, MD, PhD)

Emory University, Atlanta, GA (Saul Karpen, MD, PhD)

Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN (Jean Molleston, MD)

Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO (Ajay Jain, MD)

Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX (Sarah Barlow, MD)

University of California, San Diego, CA (Jeffrey Schwimmer, MD)

University of California, San Francisco, CA (Philip Rosenthal, MD)

University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Karen Murray, MD)

Data Coordinating Center

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (James Tonascia, PhD)

Appendix 2. List of inclusion / exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients must satisfy all of the following criteria to be eligible for enrollment:

Children age 8–17 years inclusive.

Liver biopsy within 90 days of screening visit and not more than 120 days before randomization.

Clinical history consistent with NAFLD.

Definite NAFLD based upon liver histology.

No evidence of any other liver disease by clinical history or histological evaluation

A histological severity of NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) ≥ 4.

Sexually active female participants of childbearing potential (i.e., not surgically sterile [defined as tubal ligation, hysterectomy, or bilateral oophorectomy) must agree to utilize the same two acceptable forms of contraception from screening through completion of the study and to complete a pregnancy test at each study visit. The acceptable forms of contraception for this study include hormonal contraceptives (oral, implant, transdermal patch, or injection) at a stable dose for at least 1 month prior to screening, and barrier (condom with spermicide, diaphragm with spermicide). Sexual activity will be ascertained at each study visit for post-menarchal females and if sexually active, subject must verify use of the same 2 acceptable forms of contraception.

Participants must be able to swallow cysteamine bitartrate DR capsules.

Written informed consent from parent or legal guardian.

Written informed assent from the child

Exclusion criteria

Exclusions will not be based upon gender, race, or ethnicity. Participants with a current history of the following conditions or any other health issues that make it unsafe for them to participate in the opinion of the investigators:

Inflammatory bowel disease (if currently active) or prior resection of small intestine

Heart disease (e.g., myocardial infarction, heart failure, unstable arrhythmias)

Seizure disorders

Active coagulopathy

Gastrointestinal ulcers/bleeding

Renal dysfunction with a creatinine clearance < 90 mL/min/m2

History of active malignant disease requiring chemotherapy or radiation within the past 12 months prior to randomization

History of significant alcohol intake (AUDIT questionnaire) or inability to quantify alcohol consumption

- Chronic use (defined as more than 2 consecutive weeks in the past year) of medications known to cause hepatic steatosis or steatohepatitis including:

- systemic glucocorticoids

- tetracycline

- anabolic steroids

- valproic acid

- salicylates

- tamoxifen,

The use of other known hepatotoxins within 90 days of liver biopsy or within 120 days of randomization

Initiation of medications with the intent to treat NAFLD/NASH in the time period following liver biopsy and prior to randomization

History of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) use in the year prior to screening

History of bariatric surgery or planning to undergo bariatric surgery during study duration

Clinically significant depression (patients hospitalized for suicidal ideations or suicide attempts within the past 12 months)

Any female who is nursing, planning a pregnancy, known or suspected to be pregnant, or who has a positive pregnancy screen

- Non-compensated liver disease with any one of the following hematologic, biochemical, and serological criteria on entry into protocol:

- Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL

- White blood cell (WBC) < 3,500 cells/mm3 of blood

- Neutrophil count < 1,500 cells/mm3 of blood

- Platelets < 130,000 cells/mm3 of blood

- Direct bilirubin > 1.0 mg/dL

- Total bilirubin >3 mg/dL

- Albumin < 3.2 g/dL

- International normalized ratio (INR) > 1.4

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 9%)

- Evidence of other chronic liver disease:

- Biopsy consistent with histological evidence of autoimmune hepatitis

- Serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive

- Serum hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV) positive

- Iron/total iron binding capacity (TIBC) ratio (transferrin saturation) > 45% with histological evidence of iron overload

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT) phenotype/genotype ZZ or SZ

- Wilson’s disease

Children who are currently enrolled in a clinical trial or who have received an investigational study drug within 180 days of screening or liver biopsy

Subjects who are not able or willing to comply with the protocol or have any other condition that would impede compliance or hinder completion of the study; in the opinion of the investigator

Failure to give informed consent

Appendix 3. Details on dose escalation plan by weight group

Participants who met the eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to one of two groups for 52 weeks of treatment. The dose of cysteamine bitartrate DR was assigned according to their weight group at randomization. Patients ≤ 65 kg at baseline were assigned a 600 mg/day dose and instructed to take (four 75 mg capsules twice daily); patients >65 – 80 kg were assigned a 750 mg/day dose and instructed to take five 75 mg capsules twice daily; and for patients >80 kg, were assigned a 900 mg/day dose and instructed to take six 75 mg capsules twice daily.

- Group 1: cysteamine bitartrate DR:

- 600 mg/day (four 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients ≤ 65 kg at baseline

- 750 mg/day (five 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients >65 – 80 kg at baseline

- 900 mg/day (six 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients >80 kg at baseline

- Group 2: cysteamine bitartrate DR placebo (as identical capsules to active drug)

- 600 mg/day (four 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients ≤ 65 kg at baseline

- 750 mg/day (five 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients >65 – 80 kg at baseline

- 900 mg/day (six 75 mg capsules twice daily) for patients >80 kg at baseline

Study drug dosing schedule

Participants followed a dose escalation regimen during weeks 1–4, the number of capsules taken was increased gradually to the assigned dose and remained fixed thereafter regardless of weight changes according to the following schemes:

-

For patients with a baseline weight of 65 kg or less:

Week 1: One 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (1 in the morning and 1 in the evening) (150 mg/day),

Week 2: Two 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (2 in the morning and 2 in the evening (300 mg /day)

Week 3: Three 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (3 in the morning and 3 in the evening) (450 mg/day)

Weeks 4–52: Four 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (4 in the morning and 4 in the evening) (600 mg/day)

-

For patients with a baseline weight greater than 65 kg up to 80 kg:

Week 1: Two 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (2 in the morning and 2 in the evening) (300 mg /day)

Week 2: Three 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (3 in the morning and 3 in the evening) (450 mg/day)

Week 3: Four 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (4 in the morning and 4 in the evening) (600 mg/day)

Weeks 4–52: Five 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (5 in the morning and 5 in the evening) (750 mg/day)

-

For patients with a baseline weight greater than 80 kg:

Week 1: Three 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (3 in the morning and 3 in the evening) (450 mg/day)

Week 2: Four 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (4 in the morning and 4 in the evening) (600 mg/day)

Week 3: Five 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (5 in the morning and 5 in the evening) (750 mg/day)

Weeks 4–52: Six 75 mg capsules orally twice a day (6 in the morning and 6 in the evening) (900 mg/day)

Appendix 4. List of Steering Committee members

Steering Committee:

Joel Lavine (co-chair), Columbia University

Arun Sanyal (co-chair), Virginia Commonwealth University

Susan Baker, University at Buffalo

Sarah Barlow, Texas Children’s Hospital

Elizabeth Brunt, Washington University

Naga Chalasani, Indiana University

Edward Doo, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Anna Mae Diehl, Duke University

Saul Karpen, Emory University

David Kleiner, National Cancer Institute

Kris Kowdley, Swedish Medical Center

Rohit Loomba, University of California – San Diego

Arthur McCullough, Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Jean Molleston, Indiana University

Karen Murray, University of Washington/Seattle Children’s

Philip Rosenthal, University of California – San Francisco

Claude Sirlin, University of California – San Diego

Jeffrey Schwimmer, University of California – San Diego

Norah Terrault, University of California – San Francisco

Brent Tetri, Saint Louis University

James Tonascia, Johns Hopkins University

Peter Whitington, Northwestern University

Stavra Xanthakos, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Appendix 5. Members of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network Pediatric Clinical Centers

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Stephanie H. Abrams, MD, MS (2007–2013); Sarah Barlow, MD ; Ryan Himes, MD; Rajesh Krisnamurthy, MD; Leanel Maldonado, RN (2007–2012); Rory Mahabir

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH: Kimberlee Bernstein, BS, CCRP; Kristin Bramlage, MD; Kim Cecil, PhD; Stephanie DeVore, MSPH (2009–2011); Rohit Kohli, MD; Kathleen Lake, MSW (2009–2012); Daniel Podberesky, MD (2009–2014); Alex Towbin, MD; Stavra Xanthakos, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: Gerald Behr, MD; Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD; Jay H. Lefkowitch, MD; Ali Mencin, MD; Elena Reynoso, MD

Emory University, Atlanta, GA: Adina Alazraki, MD; Rebecca Cleeton, MPH, CCRP; Saul Karpen, MD, PhD; Jessica Cruz Munos (2013–2015); Nicholas Raviele (2012–2014); Miriam Vos, MD, MSPH, FAHA

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN: Molly Bozic, MD; Oscar W. Cummings, MD; Ann Klipsch, RN; Jean P. Molleston, MD; Sarah Munson, RN; Kumar Sandrasegaran, MD; Girish Subbarao, MD

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD: Kimberly Kafka, RN; Ann Scheimann, MD

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine/Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Katie Amsden, MPH; Mark H. Fishbein, MD; Elizabeth Kirwan, RN; Saeed Mohammad, MD; Cynthia Rigsby, MD; Lisa Sharda, RD; Peter F. Whitington, MD

Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO: Sarah Barlow, MD (2002–2007); Jose Derdoy, MD (2007–2011); Ajay Jain MD; Debra King, RN; Pat Osmack; Joan Siegner, RN (2004–2015); Susan Stewart, RN (2004–2015); Susan Torretta; Kristina Wriston, RN

University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY: Susan S. Baker, MD, PhD; Lixin Zhu, PhD

University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Jonathon Africa, MD; Jorge Angeles, MD; Sandra Arroyo, MD; Hannah Awai, MD; Cynthia Behling, MD, PhD; Craig Bross; Janis Durelle; Michael Middleton, MD, PhD; Kimberly Newton, MD; Melissa Paiz; Jennifer Sanford; Jeffrey B. Schwimmer, MD; Claude Sirlin, MD; Patricia Ugalde-Nicalo, MD; Mariana Dominguez Villarreal

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Bradley Aouizerat, PhD; Jesse Courtier, MD; Linda D. Ferrell, MD; Shannon Fleck, MPH; Ryan Gill, MD, PhD; Camille Langlois, MS; Emily Rothbaum Perito, MD; Philip Rosenthal, MD; Patrika Tsai, MD

University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA: Kara Cooper; Simon Horslen, MB ChB; Evelyn Hsu, MD; Karen Murray, MD; Randolph Otto, MD; Matthew Yeh, MD, PhD; Melissa Young

Washington University, St. Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD; Kathryn Fowler, MD

Resource Centers

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD: Sherry Brown, MS; Edward C. Doo, MD; Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD; Patricia R. Robuck, PhD, MPH (2002–2011); Averell Sherker, MD; Rebecca Torrance, RN, MS

Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health (Data Coordinating Center), Baltimore, MD: Patricia Belt, BS; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; Michele Donithan, MHS; Erin Hallinan, MHS; Milana Isaacson, BS; Kevin P. May, MS; Laura Miriel, BS; Alice Sternberg, ScM; James Tonascia, PhD; Mark Van Natta, MHS; Ivana Vaughn, MPH; Laura Wilson, ScM; Katherine Yates, ScM

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions:

Study concept and design: Schwimmer, Lavine, Wilson, Xanthakos, Molleston, Brunt, Kleiner, Van Natta, Tonascia

Acquisition of data: Schwimmer, Lavine, Xanthakos, Kohli, Barlow, Vos, Karpen, Molleston, Whitington, Rosenthal, Jain, Murray, Brunt, Kleiner,

Analysis and interpretation of data: Schwimmer, Lavine, Neuschwander-Tetri, Wilson, Van Natta, Tonascia

Drafting of the manuscript: Schwimmer, Lavine, Neuschwander-Tetri, Wilson, Van Natta, Tonascia

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Schwimmer, Lavine, Neuschwander-Tetri, Wilson, Xanthakos, Kohli, Barlow, Vos, Karpen, Molleston, Whitington, Rosenthal, Jain, Murray, Brunt, Kleiner, Van Natta, Clark, Tonascia, Doo

Statistical analysis: Wilson, Van Natta, Tonascia

Obtained funding: Lavine, Neuschwander-Tetri, Tonascia,

Administrative, technical, or material support: Schwimmer, Lavine, Neuschwander-Tetri, Wilson, Xanthakos, Kohli, Barlow, Vos, Karpen, Molleston, Whitington, Rosenthal, Jain, Murray, Brunt, Kleiner, Van Natta, Clark, Tonascia, Doo

Study supervision: Schwimmer, Lavine, Wilson, Van Natta, Clark, Tonascia, Doo

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1388–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:641–649. doi: 10.1002/hep.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwimmer JB, Pardee PE, Lavine JE, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Circulation. 2008;118:277–283. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindback SM, Gabbert C, Johnson BL, et al. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive review. Adv Pediatr. 2010;57:85–140. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung DH, Shim JY, Lee HR, et al. Relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and pulmonary function. Intern Med J. 2012;42:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patton HM, Yates K, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and liver histology among children with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2093–2102. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubinstein E, Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB. Hepatic, cardiovascular, and endocrine outcomes of the histological subphenotypes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:380–385. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwimmer JB, Zepeda A, Newton KP, et al. Longitudinal assessment of high blood pressure in children with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barshop NJ, Sirlin CB, Schwimmer JB, et al. Review article: epidemiology, pathogenesis and potential treatments of paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Videla LA, Rodrigo R, Orellana M, et al. Oxidative stress-related parameters in the liver of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Clinical Science. 2005;106:261–268. doi: 10.1042/CS20030285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malaguarnera L, Madeddu R, Palio E, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 levels and oxidative stress-related parameters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. J Hepatol. 2005;42:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyons J, Rauh-Pfeiffer A, Yu Y, et al. Blood glutathione synthesis rates in healthy adults receiving a sulfur amino acid-free diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5071–5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090083297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]