Abstract

Cell polarity, often associated with polarized cell expansion/growth in plants, describes the uneven distribution of cellular components, such as proteins, nucleic acids, signaling molecules, vesicles, cytoskeletal elements and organelles, which may ultimately modulate cell shape, structure and function. Pollen tubes and root hairs are model cell systems for studying the molecular mechanisms underlying sustained tip growth. The formation of intercalated epidermal pavement cells requires excitatory and inhibitory pathways to coordinate cell expansion within single cells and between cells in contact. Strictly controlled cell expansion is linked to asymmetric cell division in zygotes and stomatal lineages, which require integrated processes of pre-mitotic cellular polarization and division asymmetry. While small GTPases ROPs are recognized as fundamental signaling switches for cell polarity in various cellular and developmental processes in plants, the broader molecular machinery underpinning asymmetric division-required polarity establishment remain largely unknown. Here, we review the widely used ROP signaling pathways in cell polar growth and the recently discovered feedback loops with auxin signaling and PIN effluxers. We discuss the conserved phosphorylation and phospholipid signaling mechanisms for protein uneven distribution, as well as the potential roles of novel proteins and MAPKs in the polarity establishment related to asymmetric cell division in plants.

Keywords: cell expansion, cytoskeleton, polarity, polarity determination, signal transduction

Short Summary

Establishing cell polarity is required for many developmental processes in plants, including sustained tip extension (pollen tubes and root hairs), diffuse cell growth (pavement cells) and regional cell expansion for asymmetric cell division (zygotes and stomatal lineages). We summarize the small GTPases-centered molecular mechanisms underpinning plant cell polarity and discuss the potential roles of other signaling pathways in asymmetric cell expansion.

Introduction

Cell polar growth, including sustained unidirectional extension (polar growth) and diffused multidirectional expansion (diffuse growth), is the basis of growth and development of an organism. Polar growth, also termed as tip growth, is achieved by localized delivery of molecular and cellular materials to the growth site, and is often required for the generation of highly elongated tubular cells, such as fungal hyphae, animal neurons, plant root hairs and pollen tubes. Diffuse growth is a more universal form of cell expansion and found in almost all cell types in eukaryotic kingdoms. Although a large number of cell expansion undergo isotropic diffuse growth (the cell extension in all directions along the cell surface) (Kropf et al., 1998), here we consider and discuss anisotropic diffuse growth, the hallmark of plant cells, which describes the differential expansion of certain region or position of the cell.

The molecular mechanism for the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity is one of the most fundamental and actively studied frontier areas in cell and developmental biology. Prior to visible cell polar growth, the establishment of cell polarity is necessary. Cell polarity is represented by the asymmetrical distribution of molecules, organelles or cytoskeletal elements along a particular axis of the cell (Grebe et al., 2001). Such organization is generally required for polar cell expansion during morphogenesis and/or specifying a distinct sub-region to fulfill a specific function in differentiated cells. While decades of work has led to extensive progress in deciphering the molecular components and genetic mechanisms governing cell polarity and regional cell growth in plants (Kania et al., 2014; Yang and Lavagi, 2012), recent research made an exciting wave of discoveries linking cell polarity to the establishment of physical and subsequent asymmetrical cell fate during cell division (Facette and Smith, 2012), which is of crucial importance for organ initiation, morphogenesis and development.

Albeit differing from other organisms in lifestyle, body organization and cellular structure, plants seem to have evolved conserved core mechanisms (small GTPases) for cell polarity control (Thompson, 2013; Yang, 2008). This review summarizes recent progresses made in several plant model systems in studying the molecular mechanisms of polar cell expansion, and provides insights in to understanding their molecular linkages to specific developmental processes.

Model Systems for Studying Polar Cell Expansion in Plants

Benefiting from the amiability to experimental manipulations, as well as ample genetic and molecular markers, quite a few excellent model cell systems in plants, particular in Arabidopsis, have been established for studying cell polarity and polar growth. Root hair cells and pollen tubes are excellent model systems for tip growth (sustained, fast cell extension behavior) (Cardenas, 2009; Guan et al., 2013; Qin and Yang, 2011). Leaf epidermal pavement cells have been established as an ideal system for cell-cell coordination of interdigitated cell expansion (Chen and Yang, 2014; Lin et al., 2014). The stomata lineages and zygotes require cellular polarization for successful asymmetric cell division, therefore are emerging as new systems for studying cell polarity (Dong and Bergmann, 2010; Zhang and Laux, 2011).

Root hairs and pollen tubes: model systems for sustained tip growth

Root hairs (RHs), originated from a subset of root epidermal cells, extend fast by tip growth at the rates of 10–40 nm/s (Galway et al., 1997). Root hairs are important in sensing external biotic/abiotic conditions and nutritional status. Pollen tubes are developed from pollen grains after landing on the floral stigma. The tube tip (growth speed at ~300 nm/s) interacts with and penetrates through several types of pistil tissue to deliver sperm cargos for double fertilization. Both pollen tubes and root hairs are easy to grow and accessible to both genetic and cell biological analysis. These tip growing systems commonly require highly polarized intracellular organization and demand continuous exocytosis, which delivers cell membrane and wall materials to the apical dome for sustained growth (Hepler et al., 2001; Qin et al., 2007). The identified genes from these systems suggest that a Rho GTPase-based self-organizing signaling network interconnected with calcium homeostasis, F-actin cytoskeleton dynamics and polarized exocytosis plays a center role in the strictly controlled tip growth (Guan et al., 2013). Root hair growth also involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Carol and Dolan, 2006; Molendijk et al., 2001). The clathrin-dependent endocytosis and cell wall modifications were also shown important for the pollen tube self-organizing growth (Bosch and Hepler, 2005; Rockel et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2010).

Pavement cells: interdigitating diffuse growth

Unlike unicellular root hair and pollen tube, pavement cells in the leaf epidermis provide an excellent platform for investigating the mechanisms for cell shape determination, during which coordinated cell growth within a single cell and between adjacent cells is necessary and regulated by both developmental and intercellular signals (Smith, 2003; Wasteneys and Galway, 2003; Yang, 2008; Yang and Fu, 2007). Particularly, establishing cell polarity is critical for the morphogenesis of leaf epidermal pavement cells. Their jigsaw-puzzle appearance results from the intercalary growth of lobes and indentations, reminiscence of the convergent extension in animal cells (Price et al., 2006; Settleman, 2005). Accumulating evidence suggested that a Rho GTPase-orchestrated and cytoplasmic auxin signaling-mediated reorganization of cortical microtubules and fine actin microfilaments underpins the formation of cellular interdigitation in plants (Fu et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2010).

Zygotes and stomatal lineage cells: cell expansion for asymmetric division

Asymmetric cell division (ACD) is at the heart of plant development for continuously generating diverse cell types. One prerequisite for a successful ACD is cell polarization (De Smet and Beeckman, 2011), represented by unequal distribution of cellular components (no striking cell shape change, e.g. some ACDs in the root apical meristem (Petricka et al., 2009)) or by anisotropic cell expansion (elongation required, e.g. zygotes and stomatal lineages).

Plants start their life from a single cell, zygote, formed by the fusion of an egg cell and a sperm cell. A zygote undergoes profound cellular reorganization to establish an apical-basal axis prior to division: from a symmetric state to an asymmetric stage with a large vacuole re-assembled at the basal end and the nucleus migrated to the apical end (Faure et al., 2002). The first asymmetric division then generates two daughter cells with distinct morphology and perspectives. The small apical daughter cell gives rise to the apical embryo lineage, and the large vacuolated basal daughter cell divides to produce an extra-embryonic structure, suspensor. Brown algae used to be a favorable system for studying zygote polarity because large populations of free-living and synchronously developing embryos can be obtained and the zygote polarity can be induced and altered by external signals (Brownlee and Bouget, 1998). The moss Physcomitrella patens has two types of bodies: a hypha-like body (protonema, undergoes tip growth) and a shoot-like body (gametophore, develops stems and leaves and requires ACD at the apical region), thus becomes a useful model system for studying polar cell growth and ACD (Vidali and Bezanilla, 2012). Facile tools are available for genic and genomic analysis in Physcomitrella (Strotbek et al., 2013). Arabidopsis zygotes for their nearly invariant division pattern have become an ideal system for studying the molecular basis underpinning cell polarity and asymmetric division at the initial and fundamental stage in plant development (Gallois, 2001). It was found that transcriptional programs in connection with the positional-cue regulated MAPK signaling regulate zygote polarity for the first asymmetric cell division (Lukowitz et al., 2004; Ueda et al., 2011).

Stomata are gas exchange valves between plants and the atmosphere. Two guard cells surround to form a stomatal pore. The initiation and differentiation of guard cell population require a series of strictly controlled asymmetric cell division in both monocot maize and dicot Arabidopsis (Dong and Bergmann, 2010). In Arabidopsis, the ACD precursor cell, Meristemoid Mother Cell (MMC), expands to set up asymmetry; a procedure involves organelle shifting, nuclear migration, and asymmetric placement of the PPB. In maize, a stomatal complex is composed of a pair of guard cells (GCs) flanked by a pair of subsidiary cells (SCs). The formation of SCs requires the precursor cells, subsidiary mother cells (SMCs), to polarize and divide asymmetrically. It was proposed that external positional cues may guide the SMCs’polarization to divide asymmetrically (Facette and Smith, 2012). In both stomatal systems, cell polarity is obviously linked to patterned stomatal asymmetric divisions (Facette and Smith, 2012). In Arabidopsis, the bHLH transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH) determines the initiation of the stomatal lineage asymmetries (MacAlister et al., 2007). The novel proteins BREAKING OF ASYMMETRY IN THE STOMATAL LINEAGE (BASL) (Dong et al., 2009) and POLAR LOCALIZATION DURING ASYMMETRIC DIVISION AND REDISTRIBUTION (POLAR) (Pillitteri et al., 2011)are employed to polarlyenrichat the cortical PM region during stomatal ACD. Another set of polarity proteins from maize were identified, PANGLOSS1 (PAN1) (Cartwright et al., 2009) and PAN2 (Zhang et al., 2012) receptor-like proteins. The PAN pathway has been linked to the functions of ROP signaling and actin organization (Humphries et al., 2011).

Establishing Polarity: Cellular Machinery and Molecular Components in Symmetry Breaking

In eukaryotes, including yeast, plants and animals, the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity are associated with common cellular components, such as the cytoskeletal elements, the endomembrane system and polarity molecules (Kania et al., 2014; Thompson, 2013). Due to the specialized wall structures, plants appear to have evolved their own polarization machineries and mechanisms, including cell wall modification, polar auxin transportation (Fowler and Quatrano, 1997; Grunewald and Friml, 2010)and plant-specific polarity factors, e.g. small GTPase ROPs (Rho of plants) (Yang and Fu, 2007) and BASL/POLAR ((Dong et al., 2009; Pillitteri et al., 2011). ROP GTPases are master molecular switches controlling cell polarization by orchestrating the behaviors of cytoskeleton, vesicle trafficking and calcium signaling (Craddock et al., 2012). In contrast to the much better understood cell polarization regulated by ROPs, how other polarity proteins coordinate asymmetric cell divisions in plants remain largely unknown. Other cellular components and signaling molecules, e.g. phospholipids and protein kinases, seem to be conserved and play important roles in symmetry breaking in both animal and plant cells.

Small GTPases

Small GTPases contain a large group of hydrolases implicated in a broad range of cellular events. GTPases function as biological switches, which constitutively cycle between the active GTP-bound form and the inactive GDP-bound form. Their activation is regulated by the guanine exchange factor (GEF) that promotes the substitution of GDP-to-GTP and the deactivation process is mediated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) that stimulate the hydrolysis of GTP-to-GDP. Another type of negative regulators, guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) prevents the PM association and nucleotide exchange of Rho GTPases (Nagawa et al., 2010). GDIs also play a role in the polarized accumulation of Rho GTPases by mediating the recycling of Rho GTPase to specific membrane domains (Klahre et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2003).

The Rho GTPase super family has evolved to several subfamilies, including Cdc42, Rac, Rho and plant specific ROP (Rho GTPase in plants). The Arabidopsis genome encodes 11 ROPs, and each seemed to function differently (Yang, 2002), with the best-described regulation in cell polarity and morphogenesis. ROP1, ROP3 and ROP5 redundantly control tip growth in pollen tubes (Gu et al., 2003; Li et al., 1999), while ROP2 overlaps with ROP4 to modulate tip growth in root hairs (Duan et al., 2010; Molendijk et al., 2001). A recent report showed that ROP3 also plays important roles in embryo development via maintaining PIN polarity at the PM (Huang et al., 2014). AlthoughROP6 and ROP2 are almost identical in sequence (94%), they function distinctly in the formation of interdigitated pavement cell shape. ROP2 promotes the formation of cortical diffuse F-actin and thus lobe outgrowth, whilst ROP6 rearranges MT organization to restrict cell growth and enhance indentation (Fu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2009). These two antagonistic Rho GTPase pathways are controlled by feedback loops of ROPs with auxin signaling and regulated by Auxin-binding protein 1 (ABP1) and transmembrane kinase (TMK) receptors (Xu et al., 2014). Interestingly, ROP11 was recently found to regulate MT reorganization for secondary cell wall patterning in xylem cells (Oda and Fukuda, 2012).

Cytoskeleton dynamics

Microtubules (MTs) and actin filaments (F-actin) are linear proteinaceous polymers that comprise the complex cytoskeleton network in plant cells. MTs are frequently found aligned with wall microfibrils that are arranged in an orientation transverse to the direction of cell expansion (Baskin, 2001). Chemical drugs that disturbed MT structure/organization induced plant cells to lose their polarity and become isotropically swollen. These defects suggested that MT is essential for establishing and maintaining growth directionality (Mathur and Chua, 2000). Another important function that MTs involve in is the Preprophase band (PPB) formation. The PPB is composed by a highly ordered cortical array of MTs and marks the cortical division site (CDS) that corresponds to the future site of cell division plane (Pickett-Heaps and Northcote, 1966). During the PPB formation, cortical F-actin assembles alongside the PPB MTs and helps them to condense at CDS. Once assembled, the PPB MTs organize proteins and lipids at the CDS to guide the orientation of the phragmoplast extension for accurate cell-plate formation (Rasmussen et al., 2013). The PPB formation per se is not significantly affected by cell polarity, but the position of the PPB placement is likely guided by the polarity cue that induces and establishes cellular asymmetry (Facette and Smith, 2012).

Functions of F-actin in cell polarity control are tightly associated with vesicle trafficking and deposition of materials to the plasma membrane (PM). In animals, F-actin, together with the associated proteins (such as spectrin, ankyrin and myosin) and the regulatory proteins (e.g. the small GTPase CDC42), helps to assemble vesicles at the Golgi and endosomes and to transport them across the cytoplasm (Musch et al., 2001). In the tip growing systems, the polarlylocalized fine F-actin at the apex is very dynamics and delivers signaling molecules, e.g. the Rho GTPases and their activators, to the apex, which in turn promotes the polymerization of F-actin (Figure 1a). Such a F-actin dynamics and vesicle trafficking coordinated feedback regulation is critical for robust cell polarity, not only conserved in yeast and animals, but also in plants (Charest and Firtel, 2006). Examples can be found in polarized growth of many plant cells. During trichome branching, the actin-dependent morphogenesis is regulated by SPIKE1 (SPK1), a ROP GEF, which activates the F-actin nucleating machinery comprised of theARP2/3 complex and its activator, the WAVE complex (Basu et al., 2008). In pollen tubes, the long actin cables, extending longitudinally through the shank region but not into the sub apical region of a tube, provide main tracks for intracellular delivery of organelles and vesicles (Cai and Cresti, 2009). F-actin appears to have more complicated roles in diffuse growth. The fine and bundled F-actins are localized differently to organize the MT orientation for restricted or promoted cell expansion, respectively (Figure 2a) (Mathur, 2006; Saedler et al., 2004). The indentation areas contain dense F-actin mesh and the vesicles with limited movement, whilst a fine F-actin mesh favors vesicle delivery, therefore promotes cell growth in the protruding regions. MTs co-localize with dense F-actin mesh and provide more physical support to enforce cell polarity (Mathur, 2006).

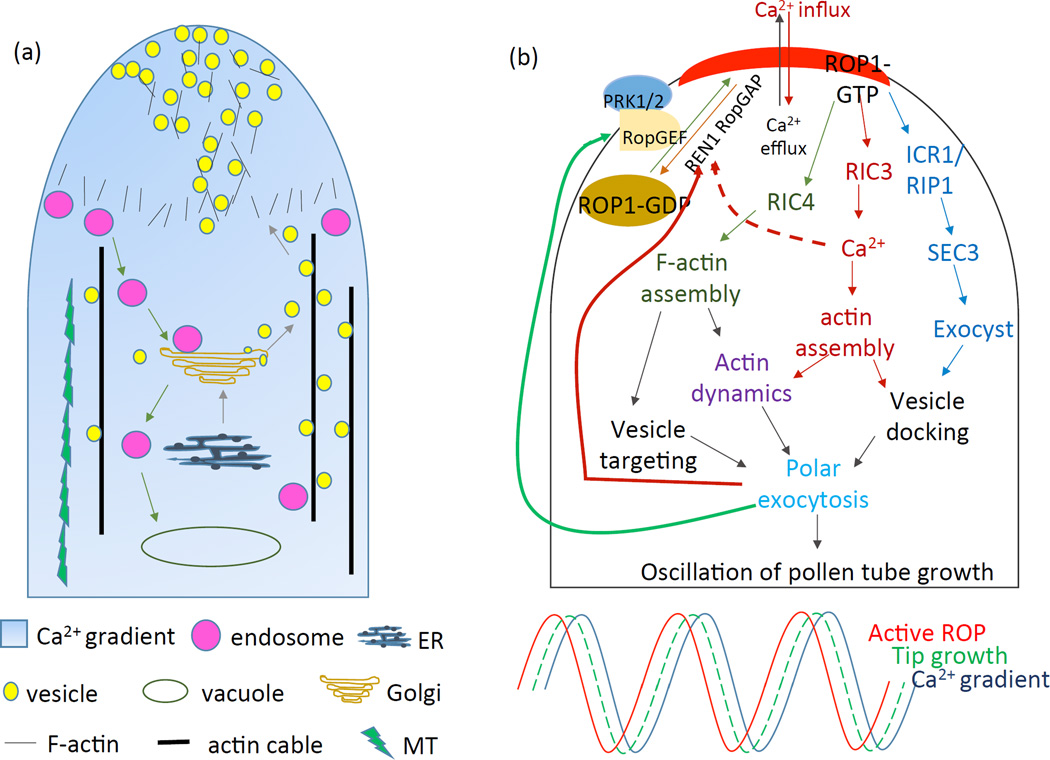

Figure 1.

An integrated model for tip growth of pollen tubes. (a) A diagram demonstrates the intracellular organization of a growing pollen tube. (b) Upper panel: a self-organizing ROP1 signaling network controls the oscillation of pollen tube tip growth. Bottom panel: the apical ROP1 activity oscillates ahead of tip growth, followed by the Ca2+ gradient oscillates.

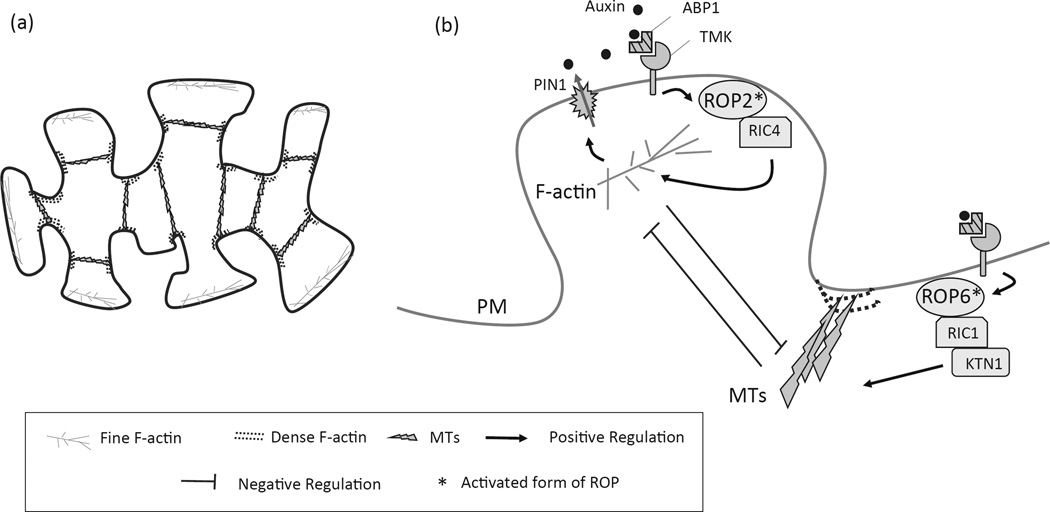

Figure 2.

The ROP small GTPases-based molecular mechanism for coordinated cell polar growth to form puzzle-shaped pavement cells. (a) Schematic representation of the cytoskeletal architecture in intercalary pavement cells. (b) A simplified model for the auxin-controlled interdigitation through antagonistic ROP2 and ROP6 pathways that direct the formation of lobes and indentations, respectively.

Vesicular trafficking

Many molecular components required for cell growth, such as proteins, enzymes, phospholipids, and polysaccharides, are produced, modified and transported through the endomembrane system, from which the vesicles containing cargo molecules are derived. The vesicles transit through the cytosol and arrive at the destination membrane, where the cargo molecules are released by membrane fusion. Therefore, polarized cell grow this highly dependent on vesicular trafficking that supplies the flow of macromolecules to the growth site (Kania et al., 2014).

Vesicular trafficking in the secretory exocytosis and recycling endocytosis pathways are highly dynamic and key to the PM integrity. Exocytosis is mediated by an evolutionarily conserved complex, the exocyst, which is responsible for vesicle tethering to the PM (Hala et al., 2008). Mutations in the exocyst subunits resulted in defective tip growth (Cole et al., 2005; Synek et al., 2006). Other regulatory components involved in vesicle budding and docking, ARF (ADP-ribosylation factors) GTPases and Rab-GTPases, respectively, are also critical for tip growth (Preuss et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2005). In addition, the spatial and temporal changes of exocytosis are coordinated by the activities of cytoskeleton, ROP GTPases, calcium and phospholipids in root hairs and pollen tubes (Lee et al., 2008; Monteiro et al., 2005). Excessive signaling molecules and wall materials deposited into the plasma membrane must be retrieved by endocytosis (Goldstein et al., 1979). The clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is the predominant endocyticroute in plants and has tremendous impacts on establishing and sustaining cell polarity (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011). This can be well exemplified by the process of PIN (PIN-FORMED) protein polarization. PIN proteins are auxin transporters that are polarly localized in plant cells to drive directional auxin flow. Blocking endocytosis by inhibitors resulted in lateral diffusion of PIN proteins from the polar domains. Recent studies illustrated that the auxin-dependent endocytosis of PIN proteins is under the orchestrated activities of the putative auxin receptor ABP1 and ROP GTPases (Chen et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012; Murphy and Peer, 2012; Nagawa et al., 2012).

Phosphorylation and phospholipid signaling

Besides the small GTPase-centered cell polarization mechanisms, protein phosphorylation has been recognized as an important mechanism to regulate protein polarization in both animals and plants. In animals, the conserved PAR proteins are fundamental players to regulate cell polarity in different developmental and functional contexts (Goldstein and Macara, 2007). In C. elegans embryos, PAR polarity regulators are sorted into anterior and posterior cortical domains. The anterior PAR kinase (aPKC) phosphorylates the posterior PAR-2 to prevent its cortical association (Hao et al., 2006), and the posterior PAR-2 recruits PAR-1 kinases, which phosphorylates and locally dissembles anterior PAR-3 to prevent its accumulation at the posterior domain (Cuenca et al., 2003). Therefore, protein phosphorylation-mediated mutual exclusion plays a pivotal role in segregating the PAR polarity domains. Interestingly, in plant cells, polar localization of PIN proteins to the apical or basal domains of the PM also relies on their phosphorylation status (Friml et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). The AGC-3 serine/threonine kinases, PINOID (PID), WAVY ROOT GROWTH1 (WAG1) and WAG2, redundantly phosphorylate PIN proteins to direct them to the apical membrane (Dhonukshe et al., 2010; Michniewicz et al., 2007; Sukumar et al., 2009). On the other hand, the trimeric protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and D6 protein kinase (D6PK) function antagonistically to dephosphorylate and phosphorylate PINs, respectively, and target them to the basal side (Dai et al., 2012; Michniewicz et al., 2007; Zourelidou et al., 2009). The loss-of-function mutations in these kinases and phosphatases commonly led to aberrant embryo patterning or agravitropic root growth, recapitulating the defects in the auxin transport mutants (Dhonukshe et al., 2010; Sukumar et al., 2009).

Phospholipid signaling has also been recognized as a signature event in cell polarization. Different phosphoinositides are found to associate with different membrane compartments, e.g. PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 are generally found at the PM (Orlando and Guo, 2009). Multiple PAR proteins, including PAR-1, PAR-2 and PAR-3, contain motifs that can bind to phospholipids (Moravcevic et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2007a). Some lipid-binding domains are enriched with basic amino acids, raising the possibility of electrostatic interactions mediating the PAR proteins to associate with the PM (Hao et al., 2006; Krahn et al., 2010). In Drosophila epithelial cells, phosphoinositides, e.g. phosphatidylinositol- 4,5- diphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), are asymmetrically distributed. Inactivating the PI4P5 kinase Skittles (SKTL) resulted in strongly reduced PI(4,5)P2 levels in the epithelium, which disturbed the apical targeting of PAR-3 to the PM followed by cell polarity and shape defects (Claret et al., 2014). Interestingly, PI(4,5)P2 seemed to play a role in polarizing PIN proteins in plants as well. PINOID, the AGC kinase targeting PINs, is recruited to the PM through interacting the upstream kinase, 3-phosphoinositide- dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1), which contains a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain that binds to PI(4,5)P2 phospholipids (Zegzouti et al., 2006). Thus, functions of membrane-localized phospholipids are connected to PID and PINs for auxin-mediated downstream signaling events (Anthony et al., 2004). In root hairs and pollen tubes, phospholipids are implicated in multiple events to regulate cell polarity, including actin cytoskeleton organization, clathrin-dependent endocytosis, vacuolar degradation and ion channel permeability (Ischebeck et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2010).

Molecular Mechanisms Underpinning Polar Growth in Plants

Differing from other mobile life styles, plants are sessile. Plant cells, once produced, are fixed in position and share cell walls with the neighboring cells, and the rigid cell walls impose spatial constrains on cell expansion and polarization. In response to various developmental and environmental cues, plant cells are capable of constantly adjusting their polar domains, which naturally requires intricate and flexible molecular mechanisms that modulate cell polarity. More than a decade of work disclosed that a few key principles in polarity signaling, e.g. positive feedback loops and mutual antagonism, are commonly applicable to animals, fungi and plants.

Tip growth: ROP signaling integrates cytoskeleton dynamics, calcium gradient and ROS production

The apical region of tip growth is defined by active ROP GTPases, which activate multiple downstream pathways to define the polar site and to precisely control exocytosis (Li et al., 1998; Molendijk et al., 2001). Disruption of active ROP GTPase inhibited tip growth, while overexpression of a constitutively active form, but not a native form, induced balloon-shaped (de-polarized) growth in root hairs and pollen tubes (Jones et al., 2002; Li et al., 1999). These data suggested that both positive and negative regulations are required for maintaining an optimal level of active ROPs to sustain polar growth.

The rapid tip growth in root hairs and pollen tubes is restricted to the very apex and interestingly exhibits an oscillating manner (episodes of fast growth followed by slower growth) (Monshausen et al., 2008). These oscillatory phenomena were widely used in ordering of signaling events, but are not necessarily essential to growth. In pollen tubes, such growth oscillation is led by an oscillation of ROP1 activity (Figure 1b) (Hwang et al., 2005). ROP1 oscillation can be well explained by the activities of its downstream effectors, RIC3 and RIC4, through two counteracting pathways: 1) the RIC4 pathway promotes F-actin assembly and 2) the RIC3 pathway is related to calcium signaling and promotes F-actin disassembly (Gu, 2005). ROP1 also activates a downstream effector, RIP1/ICR1, which promotes the accumulation of exocytic vesicles to the growing tip (Lavy et al., 2007). These vesicles may contain ROP1 upstream components, such as Rop GEFs, PRK1 and PRK2, to further activate ROP1(Gu, 2006; Kaothien et al., 2005; Zhang and McCormick, 2007), forming a positive feedback loop. In the meanwhile, to achieve unidirectional growth, negative feedback mechanisms were found to limit the lateral propagation of ROP1 signaling. A global inhibition mechanism governed by ROP1 negative regulators, RopGAPs (RopGTPase activating proteins) and RhoGDIs (Rho guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors), was demonstrated (Hwang et al., 2008). Alateral inhibition mechanism mediated by ROP1 negative regulators was also proposed to act at the tube flank region to limit the lateral propagation of active ROP1 (Hwang et al., 2010).

It has been well characterized that, in pollen tubes and root hairs, cytosolic calcium forms a tip-focused gradient and the elimination of it leads to growth arrest (Pierson et al., 1996). Interestingly, the concentration of apical calcium also fluctuates following the ROP1 activity oscillation (Hwang et al., 2005). It was suggested that ROP1 activates the downstream effector RIC3, which then mediates the influx of calcium across the PM. The tip-focused calcium in turn promotes F-actin dynamics to elevate exocytosis and ROP1 activities, forming a positive feedback loop. On the other hand, elevated calcium may suppress ROP1 activity via the negative feedback regulation, either through F-actin disassembly or through RhoGAPs (Gu, 2005; Yan et al., 2009). Then, how calcium gradient and oscillation are perceived? A couple of putative sensor proteins, such as calmodulin (CaM), CaM-like (CML), calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK), and calcineurin B-like protein (CBL), were found to mediate the downstream signaling responses and required for pollen tube growth (Myers et al., 2009; Rato et al., 2004; Yoon et al., 2006). However, the regulatory mechanisms of calcium sensors and their relationship with ROP1 signaling remain unclear.

Another signaling pathway that integrates ROP and calcium in polar growth is by ROS (reactive oxygen species) production. Intracellular and extracellular ROS play important roles in multiple cellular responses, including the hypersensitive response, programmed cell death, hormonal signaling, stomata opening and ion channel activity (Mittler and Berkowitz, 2001). Plant NADPH oxidases, the key enzymes in the generation of superoxide radicals, are membrane bound proteins and polarized to the tips, the elimination of which causes the inhibition of root hair and pollen tube growth (Foreman et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2007; Kaya et al., 2014; Potocky et al., 2007). The roles of ROS were connected to calcium signaling, modulating cell wall properties and ROP feedback regulations (Kosami et al., 2014). To further elucidate how ROS determines cell polarity for growth, investigating the relationship between ROS production and ROP GTPase activation at specific site in polarized cells become necessary.

Diffuse growth: auxin signaling linked to ROP-centered interdigitating cell growth

In contrast to the tip-growing unicellular systems, interdigitation of pavement cells in the leaf epidermis involves coordinated intracellular and cell-cell signaling. Before pavement cell expands and matures, multiple polarity sites define the interdigitated regions for the formation of complementary lobes and indents (Figure 2a). The lobes of one cell expand into the indents of the neighboring cells, generating the jigsaw-puzzle appearance of pavement cells. How multiple polarity sites are initiated and coordinated within and between cells are of fundamental importance for unraveling the developmentally programmed cellular events. Intriguingly, recent progresses bridged the phytohormone auxin signaling with the ROP-centered polarity establishment and brought new insights into the important roles of self-organizing auxin signaling in promoting the intercalary growth of pavement cells (Figure 2b) (Lin et al., 2013; Nagawa et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2010).

Experimental data showed that the formation of lobes and indentations in leaf pavement cells was promoted by auxin and compromised in the mutants defective in auxin biosynthesis or perceiving (Xu et al., 2010). It was found that the extracellular auxin is perceived by a cell surface receptor complex composed of the PM-associated auxin binding protein 1 (ABP1) and its partner, the transmembrane receptor–like kinases (TMKs) (Xu et al., 2014). Interestingly, the cytoplasmic auxin signaling activates two Rho GTPases, ROP2 and ROP6, which are polarized at lobes and indentations, respectively, to antagonistically promote or restrict local cell expansion during morphogenesis (Figure 2b) (Fu et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2010). Once activated by auxin signaling, ROP2 at the lobe protruding region interacts with RIC4 to promote the assembly of cortical F-actin for localized lobe outgrowth, in part resembling the behavior of ROP1 in pollen tube tips (Fu et al., 2005; Gu, 2005). On the other hand, the activated ROP6 in the indentation region directly activates RIC1 to promote well-ordered cortical MTs that locally restrict cell expansion to reinforce the indentation formation (Fu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2009). Recently, a MT-severing protein, Katanin (KTN1), directly binds to RIC1 to detach branched MTs, further promoting MT ordering in the indentation procedure (Lin et al., 2013). Furthermore, as the antagonistic ROP6-RIC1 and ROP2-RIC4 pathways need to coordinate and reinforce the intercalated patterning, the lobe localized ROP2 inactivates RIC1 to suppress the well-ordered cortical MTs formation in the lobe regions (Fu et al., 2005). Meanwhile, the indentation localized ROP6-RIC1 triggered MT arrays to locally suppress ROP2 activation (Fu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2009). Therefore, the jigsaw-puzzle shape of pavement cells is strictly regulated by a mutually exclusive system of antagonistic activity of ROP2-RIC4 and ROP6-RIC1 in the lobes and the indentations, respectively (Figure 2b).

In principle, ROPs and PINs, as two classes of polarity proteins, control cell polarization in different manners and regulate different developmental aspects. Intriguingly, recent progress further emphasized that these two pathways do crosstalk (Hazak et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2014; Nagawa et al., 2012). In pavement cells, PIN1 is preferentially localized to the PM of the lobe regions, overlapping with ROP2, and mutations in PIN1 resulted in reduced ROP2 activity and defects in pavement cell interdigitation (Nagawa et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2010). The auxin-dependent local activation of ROP2 at the lobe tip, through RIC4-meditated F-actin accumulation, inhibits PIN1 endocytosis and promotes PIN1 enrichment at the lob tip, which further exports more auxin for ROP2 activation. Therefore, auxin-ABP1/TMKs-ROP2-PIN1 forms a positive feedback loop that reinforces the ROP2 self-organization and cell polarization (Nagawa et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2010). Another component ICR1, a Rho scaffold protein, likely functions downstream of ROP signaling and links the secretory system to the recruitment of PIN proteins to the PM polar domains (Hazak et al., 2010).

Asymmetric cell division (ACD): MAPKs, transcription factors, auxin signaling polarity proteins, and ROPs in establishing cell polarity

ACD provides the molecular basis for cell type diversification in plant development; therefore understanding the underpinning molecular mechanisms is critical. Among a few major cell systems for studying ACD (De Smet and Beeckman, 2011), the division of zygotes and stomatal lineage cells requires the precursor cell to elongate (symmetry breaking) and the division plane to be placed asymmetrically. However, in contrast to the above well studied polarity systems toward understanding the cellular machineries for morphogenesis, our knowledge of the cell polarization mechanisms for asymmetric cell division remains limited. Here, we will first discuss the possible functions of MAPK pathway and auxin signaling, at the transcriptional level and at the sub cellular level, for the establishment of cell polarity during asymmetric division of Arabidopsis zygotes. We will then discuss the functions of polarized proteins in stomatal lineage cells and their potential connections to the ROP signaling. While seeking genetic regulators in embryogenesis, a few mutants defective in the first zygote ACD were isolated in Arabidopsis, suggesting a pathway composed of the PM receptor kinases, downstream MAPK components, and nuclear transcription factors (Bayer et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2011; Lukowitz et al., 2004). The common defects of these mutants were the failure in zygote elongation prior to the asymmetric cell division and the subsequent abnormal embryo patterning. The involved canonical mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is composed of three tiers of kinases, the MAPKKK YODA (YDA), MAPK Kinases 4 and 5 (MKK4/5), and MAPK 3 and 6 (MPK3/6). This pathway is also critical for other developmental processes that require ACD, e.g. stomatal development (Bergmann et al., 2004)and root apical meristem organization (Smekalova et al., 2014). In the loss-of-function mutants of the YDA MAPK pathway, zygote elongation is compromised and two daughter cells are about equal size, leading to disturbed developmental fate adoption (Lukowitz et al., 2004). Upstream of YDA, the PM-located interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase/Pelle-like kinase, SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP) a paternal-derived signaling molecule, delivers signals to the cytoplasm (Smekalova et al., 2014). The extracellular peptides, Embryo Surrounding Factor 1 (ESF1), derived from the maternal central cell were placed upstream of YDA, working synergistically with SSP, to regulate early embryo patterning (Costa et al., 2014). Downstream of YDA, it was found that the putative RWP-RK transcription factor GROUNDED (GRD), also called RKD4 ((Waki et al., 2011)), functions in the nucleus to promote zygote elongation and the basal cell fate (Jeong et al., 2011). The molecular mechanisms of the YDA-centered pathway in promoting zygote cell expansion and ACD still remain elusive, but the downstream events may include the activation of the transcription factor WRKY2, which acts upstream of other transcription factors, such as the WOX family.

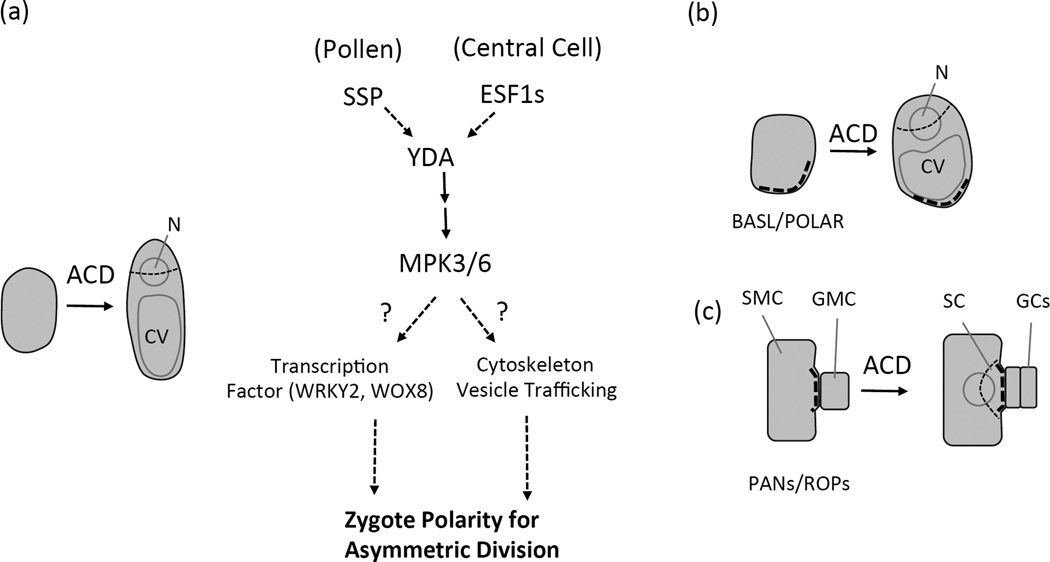

The plant-specific WUSCHEL family transcription factors, WOX (WUSCHEL HOMEOBOX), were found to control the differential lineage fate after the zygote ACD (Figure 3a) (Haecker et al., 2004). WOX2 determines the apical lineage (embryo) patterning, whereas WOX8 (also named STIMPY-LIKE)together with its close homolog WOX9 (also called STIMPY) (Wu et al., 2007b) specify the basal lineage (the extra-embryonic suspensor) and also the apical lineage via non-cell autonomous activation of WOX2 (Breuninger et al., 2008). Prior to the zygote ACD and upstream of WOX8, a plant-specific zinc-finger transcription factor WRKY2 determines the asymmetric organelle distribution and subsequent division of the zygote, suggesting an intriguing connection between the WRKY2 and WOX8transcription factors and the downstream effectors in establishing cell polarity (Ueda et al., 2011). WRKY2 contains several consensus MAP kinase phosphorylation sites and its homologues, WRKY33 and WRKY34, are found targeted by MPK3 and MPK6(Guan et al., 2014; Mao et al., 2011). Although WRKY2 has been genetically placed downstream of MPK6 in pollen development (Guan et al., 2014), the direct connection between the YDA pathway and WRKY2 and the genetic network that WRKY2 controls in the process of zygote polarization a waits further investigation (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Zygote and stomatal lineage system: cell polarity formation and asymmetric cell division (ACD). (a) Schematic depiction of zygote ACD (left) and the hypothesized genetic mechanisms in polarity formation (right). (b–c) Schematic depiction of stomatal ACD in Arabidopsis (b) and maize (c). Thick dashed lines in (b–c) indicate where the polarity complexes, BASL/POLAR and PANs/ROPs, are localized. CV, central vacuole. N, nucleus. SMC, subsidiary mother cell. SC, subsidiary cell. GMC, guard mother cell. GCs, guard cells.

Is auxin involved in establishing zygote asymmetry? The early involvement of auxin is indicated by the lack of zygote elongation and occasional symmetric divisions caused by the mutations in Arabidopsis GNOM (GM), which encodes an ARF/GEF factor for vesicle trafficking of PIN1 (Friml et al., 2003; Geldner et al., 2004). In addition, the expressions of IAA, an auxin response factor, and ABP1 receptor were detected in the tobacco zygote, and the polar distribution and transportation of auxin begins at the zygote stage and affects the following asymmetric division (Chen et al., 2010). Although, after the first zygotic division, auxin was found to transport upwards to the apical cell, likely by apically localized PIN7 in the basal cell (Friml et al., 2003), it remains to be determined whether auxin regulates zygote cell polarity before the division. Besides auxin, otherpolarly distributed developmental determinants may also be important for zygote asymmetric division. For example, polarlyenriched actin patches, vesicles and cell wall modifiers involve in axis fixation in the zygote of Fucus (Kropf, 1997). In tobacco, specific arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), potentially implicated in cell expansion, were preferentially localized at the apical pole of tobacco zygotes. Inactivating AGP activity by chemical inhibitors in in vitro cultured zygotes frequently resulted in more symmetrical divisions (Qin and Zhao, 2006).

In stomatal ACD, the direct evidence supporting the critical roles of polarity elements came from the identification of the landmark proteins, BASL/POLAR in Arabidopsis (Dong et al., 2009; Pillitteri et al., 2011)and PAN1/PAN2 in maize (Cartwright et al., 2009; Humphries et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). Both BASL and POLAR proteins are unknown of function and these two proteins largely overlap in accumulating into crescents at the cell cortex of stomatal ACD precursor cells (Figure 3b). Based on protein localization, loss-of-function mutant and overexpression phenotypes, BASL’s function was proposed to induce cortical cell expansion in the process of establishing physical asymmetry in the ACD precursor cell (Dong et al., 2009). As BASL-induced regional cell expansion was greatly compromised while ROP signaling was disturbed in Arabidopsis, it was also hypothesized that BASL might signal through or crosstalk with the ROP pathways to control cell polar expansion (Dong et al., 2009). But the key link between BASL and ROPs is still missing.

Then, what activates the polarization of BASL and POLAR? Recently, Lau et al., showed that the SPCH transcription factor directly binds to the promoter regions of BASL and POLAR, as well as those of many other key stomatal regulators, emphasizing the direct roles of SPCH in controlling stomatal division and fate differentiation (Lau et al., 2014). This work did not address how BASL polarity is induced, but intriguingly one of the SPCH targets, ARK3/AtKINUa, encodes a plant-specific kinesin, the expression of which was found at the PPB of the asymmetrically dividing stomatal lineage cells. Interfering the ARK3 function by artificial microRNA resulted in disturbed stomatal ACD, phenocopying that of a basl mutant (Lau et al., 2014). It would be interesting to elucidate whether and how BASL and ARK3 may function coordinately to achieve division asymmetries in Arabidopsis. But, as BASL polarity appears prior to the asymmetric division and presumably before the appearance of ARK3 at the PPB, dissecting the BASL/POLAR polarity complex might more directly address how cellular asymmetry and polar cell expansion are achieved at the molecular level.

In maize stomatal development, PAN1 and PAN2 are receptor-like proteins expressed in SMCs and polarized to the plasma membrane region adjacent to GMCs. In pan1 and pan2 mutants, the polarization of SMC divisions are affected, likely due to the defects of SMCs in perceiving the extrinsic signal from GMCs and/or the failure in transducing the polarization signal internally (Cartwright et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). It is still unknown how PAN proteins are polarized, but new insights have been provided by their functional connection with ROP signaling and F-actin organization (Humphries et al., 2011). It was found that maize ROPs (2 and 9) physically bind to PAN1 and are asymmetrically distributed to the SMC-GMC contact site (Figure 3c). Enriched ROPs may stimulate local F-actin assembly to form patches and promote the localized accumulation and fusion of vesicles (Humphries et al., 2011).

MAPKs as pivotal players in zygotic and stomatal ACD, besides modulating transcription factors, are they possibly involved in the regulation of cytoskeletal network and vesicle trafficking, the two fundamental processes in cell polarization? In fact, bi-directional signaling between MAPK cascades and the cytoskeleton was found important for cellular activities, such as cell division and polarized growth (Samaj et al., 2004). MAPKs physically associate with the MT cytoskeleton (Reszka et al., 1995) and, interestingly, the pool of MAPKs associated with MTs have higher activities (Morishima-Kawashima and Kosik, 1996). In plants, multiple lines of evidence supported that MAPKs are involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement during cytokinesis, e.g. MAPKs are co-localized with MTs and interact with the MT-associated protein, MAP65(Beck et al., 2011). The best-studied MAPK module in cytoskeletal regulation in plants is the tobacco NACK-PQR pathway during cytokinesis (Nishihama et al., 2002; Takahashi et al., 2004). The working model describes that the kinesin-related proteins interact with MAPKKK to activate the MAPK signaling cascade, which then phosphorylates MAPK65, a family of MT-crosslinking proteins, to control the rate of phragmoplast expansion (Nishihama et al., 2002; Takahashi et al., 2004). Arabidopsis MPK6, a kinase functionally redundant with MPK3 in zygote, root and stomatal development, was also shown to co-localize with MTs and disturbing MPK6 function caused disrupted division plane orientation in roots (Muller et al., 2010), resembling that of the loss-of-function yda (Smekalova et al., 2014).

The p38 MAPK of animal cells and MPK1 of budding yeast are the prominent examples of MAPKs controlling the polarization of actin cytoskeleton (Mazzoni et al., 1993; Zarzov et al., 1996), but such a connection in plants has not been well established yet. One example is that the stress-induced MAPK (SIMK) in Madicago was translocated from the nucleus to the growth tip and co-localized with the enriched F-actin network during root hair formation. Altering F-actin dynamics affected SIMK activity and overexpression of active SIMK enhanced root hair growth (Samaj et al., 2002). The involvement of MAPK signaling in the secretory pathway was recently suggested by screening a RNA interference of kinases and phosphatases in human HeLacells (Farhan et al., 2010). The extracellular signal-regulated kinase, MAPK/ERK, may target Sec16, a key regulatory component for vesicle biogenesis (Farhan et al., 2010). In plants, there were signs of MAPKs functioning in vesicle delivery for root hair growth (Samaj et al., 2002), but clearly further advances require the identification of MAPK substrates that are possibly involved in cell morphogenesis. The cell biology of MAPKs has recently caught the attention of the field and is expected to expand in the near future (Samajova et al., 2013).

Perspectives and Future Directions

Rapid progress toward understanding the cellular signaling mechanisms for polarity formation using several model systems in plants has been achieved in recent years, there is yet much to learn about the mechanisms of how plants initiate, maintain, and alter cell polarity in response to developmental cues and prevailing environments. Important questions remain to be addressed, for instance, besides auxin, whether and how other plant hormones may influence ROP-centered polarity regulation. What environmental cues may inform and integrate into the intrinsic cellular reorganization machineries to influence cell morphogenesis in plant development?

The coordination between positive feedback and mutual antagonism appears to be broadly used in organizing cell polarity in plants and other organisms. This is particularly well demonstrated by the small GTP-based signaling network in tip growth and diffuse growth of plant cells. Though, it is still not fully clear about how cytoskeleton dynamics and vesicular trafficking may feedback to the ROP signaling pathways, how ROP signaling are triggered by the intrinsic or extrinsic polarity cues, and how they are linked to the polarity signaling mechanisms. Mean while, we barely know anything about the feedback loops and antagonistic regulations in the polarity protein-centered asymmetry establishment for ACD. Considering the crucial roles of MAPKs in asymmetric cell division and possibly in polarity establishment in zygote, stomata and root apical meristem, it is anticipated that direct downstream substrates of MAPKs may function together or regulate cytoskeleton network and vesicle trafficking processes. It remains to be determined how the mechanisms discovered in the model systems, such as Arabidopsis, Drosophila and C. elegans, are modified in different developmental contexts of other organisms. Future studies would require the combination of genetic, molecular and cytological tools with computational modeling along experimental testing to provide new insights into these unresolved questions.

Acknowledgments

We apologized for the work not being cited in this review due to the size limit. Y.Q. is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2011CB944603; 2012CB944801), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170290; 31470284) and Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Fujian Province University (JA14096). J.D. is supported by grants from the U.S. National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM109080) and Rutgers University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anthony RG, Henriques R, Helfer A, Meszaros T, Rios G, Testerink C, Munnik T, Deak M, Koncz C, Bogre L. A protein kinase target of a PDK1 signalling pathway is involved in root hair growth in Arabidopsis. The EMBO journal. 2004;23:572–581. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI. On the alignment of cellulose microfibrils by cortical microtubules: a review and a model. Protoplasma. 2001;215:150–171. doi: 10.1007/BF01280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu D, Le J, Zakharova T, Mallery EL, Szymanski DB. A SPIKE1 signaling complex controls actin-dependent cell morphogenesis through the heteromeric WAVE and ARP2/3 complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:4044–4049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710294105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer M, Nawy T, Giglione C, Galli M, Meinnel T, Lukowitz W. Paternal control of embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2009;323:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1167784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Komis G, Ziemann A, Menzel D, Samaj J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 is involved in the regulation of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubule transitions in Arabidopsis thaliana. The New phytologist. 2011;189:1069–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann DC, Lukowitz W, Somerville CR. Stomatal development and pattern controlled by a MAPKK kinase. Science. 2004;304:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1096014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Hepler PK. Pectin methylesterases and pectin dynamics in pollen tubes. The Plant cell. 2005;17:3219–3226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger H, Rikirsch E, Hermann M, Ueda M, Laux T. Differential expression of WOX genes mediates apical-basal axis formation in the Arabidopsis embryo. Developmental cell. 2008;14:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee C, Bouget FY. Polarity determination in Fucus: from zygote to multicellular embryo. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:179–185. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai G, Cresti M. Organelle motility in the pollen tube: a tale of 20 years. Journal of experimental botany. 2009;60:495–508. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas L. New findings in the mechanisms regulating polar growth in root hair cells. Plant signaling & behavior. 2009;4:4–8. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.1.7341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carol RJ, Dolan L. The role of reactive oxygen species in cell growth: lessons from root hairs. Journal of experimental botany. 2006;57:1829–1834. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright HN, Humphries JA, Smith LG. PAN1: a receptor-like protein that promotes polarization of an asymmetric cell division in maize. Science. 2009;323:649–651. doi: 10.1126/science.1161686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest PG, Firtel RA. Feedback signaling controls leading-edge formation during chemotaxis. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2006;16:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Ren Y, Deng Y, Zhao J. Auxin polar transport is essential for the development of zygote and embryo in Nicotiana tabacum L. and correlated with ABP1 and PM H+-ATPase activities. Journal of experimental botany. 2010;61:1853–1867. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Yang Z. Novel ABP1-TMK auxin sensing system controls ROP GTPase-mediated interdigitated cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Small GTPases. 2014;5 doi: 10.4161/sgtp.29711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Naramoto S, Robert S, Tejos R, Lofke C, Lin D, Yang Z, Friml J. ABP1 and ROP6 GTPase signaling regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis in Arabidopsis roots. Current biology : CB. 2012;22:1326–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret S, Jouette J, Benoit B, Legent K, Guichet A. PI(4,5)P2 produced by the PI4P5K SKTL controls apical size by tethering PAR-3 in Drosophila epithelial cells. Current biology : CB. 2014;24:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RA, Synek L, Zarsky V, Fowler JE. SEC8, a subunit of the putative Arabidopsis exocyst complex, facilitates pollen germination and competitive pollen tube growth. Plant physiology. 2005;138:2005–2018. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LM, Marshall E, Tesfaye M, Silverstein KA, Mori M, Umetsu Y, Otterbach SL, Papareddy R, Dickinson HG, Boutiller K, et al. Central cell-derived peptides regulate early embryo patterning in flowering plants. Science. 2014;344:168–172. doi: 10.1126/science.1243005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock C, Lavagi I, Yang Z. New insights into Rho signaling from plant ROP/Rac GTPases. Trends in cell biology. 2012;22:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca AA, Schetter A, Aceto D, Kemphues K, Seydoux G. Polarization of the C. elegans zygote proceeds via distinct establishment and maintenance phases. Development. 2003;130:1255–1265. doi: 10.1242/dev.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Zhang C, Kania U, Chen F, Xue Q, McCray T, Li G, Qin G, Wakeley M, Terzaghi W, et al. A PP6-type phosphatase holoenzyme directly regulates PIN phosphorylation and auxin efflux in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2012;24:2497–2514. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I, Beeckman T. Asymmetric cell division in land plants and algae: the driving force for differentiation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:177–188. doi: 10.1038/nrm3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Huang F, Galvan-Ampudia CS, Mahonen AP, Kleine-Vehn J, Xu J, Quint A, Prasad K, Friml J, Scheres B, et al. Plasma membrane-bound AGC3 kinases phosphorylate PIN auxin carriers at TPRXS(N/S) motifs to direct apical PIN recycling. Development. 2010;137:3245–3255. doi: 10.1242/dev.052456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Bergmann DC. Stomatal patterning and development. Current topics in developmental biology. 2010;91:267–297. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)91009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, MacAlister CA, Bergmann DC. BASL controls asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;137:1320–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu HM. FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:17821–17826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005366107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facette MR, Smith LG. Division polarity in developing stomata. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan H, Wendeler MW, Mitrovic S, Fava E, Silberberg Y, Sharan R, Zerial M, Hauri HP. MAPK signaling to the early secretory pathway revealed by kinase/phosphatase functional screening. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;189:997–1011. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure JE, Rotman N, Fortune P, Dumas C. Fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana wild type: developmental stages and time course. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology. 2002;30:481–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J, Demidchik V, Bothwell JH, Mylona P, Miedema H, Torres MA, Linstead P, Costa S, Brownlee C, Jones JD, et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature. 2003;422:442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature01485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JE, Quatrano RS. Plant cell morphogenesis: plasma membrane interactions with the cytoskeleton and cell wall. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Vieten A, Sauer M, Weijers D, Schwarz H, Hamann T, Offringa R, Jurgens G. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2003;426:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Yang X, Michniewicz M, Weijers D, Quint A, Tietz O, Benjamins R, Ouwerkerk PB, Ljung K, Sandberg G, et al. A PINOID-dependent binary switch in apical-basal PIN polar targeting directs auxin efflux. Science. 2004;306:862–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Gu Y, Zheng Z, Wasteneys G, Yang Z. Arabidopsis Interdigitating Cell Growth Requires Two Antagonistic Pathways with Opposing Action on Cell Morphogenesis. Cell. 2005;120:687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Xu T, Zhu L, Wen M, Yang Z. A ROP GTPase Signaling Pathway Controls Cortical Microtubule Ordering and Cell Expansion in Arabidopsis. Current Biology. 2009;19:1827–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallois P. Future of early embryogenesis studies in Arabidopsis thaliana. Comptes rendus de l'Academie des sciences. Serie III, Sciences de la vie. 2001;324:569–573. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(01)01327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galway ME, Heckman JW, Jr, Schiefelbein JW. Growth and ultrastructure of Arabidopsis root hairs: the rhd3 mutation alters vacuole enlargement and tip growth. Planta. 1997;201:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01007706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldner N, Richter S, Vieten A, Marquardt S, Torres-Ruiz RA, Mayer U, Jurgens G. Partial loss-of-function alleles reveal a role for GNOM in auxin transport-related, post-embryonic development of Arabidopsis. Development. 2004;131:389–400. doi: 10.1242/dev.00926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Macara IG. The PAR proteins: fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Developmental cell. 2007;13:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Anderson RG, Brown MS. Coated pits, coated vesicles, and receptor-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 1979;279:679–685. doi: 10.1038/279679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe M, Xu J, Scheres B. Cell axiality and polarity in plants--adding pieces to the puzzle. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:520–526. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald W, Friml J. The march of the PINs: developmental plasticity by dynamic polar targeting in plant cells. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:2700–2714. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. A Rho family GTPase controls actin dynamics and tip growth via two counteracting downstream pathways in pollen tubes. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;169:127–138. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. Members of a Novel Class of Arabidopsis Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors Control Rho GTPase-Dependent Polar Growth. The Plant cell. 2006;18:366–381. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Vernoud V, Fu Y, Yang Z. ROP GTPase regulation of pollen tube growth through the dynamics of tip-localized F-actin. Journal of experimental botany. 2003;54:93–101. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Guo J, Li H, Yang Z. Signaling in pollen tube growth: crosstalk, feedback, and missing links. Molecular plant. 2013;6:1053–1064. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Meng X, Khanna R, LaMontagne E, Liu Y, Zhang S. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by MAPKs is required for pollen development and function in Arabidopsis. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haecker A, Gross-Hardt R, Geiges B, Sarkar A, Breuninger H, Herrmann M, Laux T. Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2004;131:657–668. doi: 10.1242/dev.00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hala M, Cole R, Synek L, Drdova E, Pecenkova T, Nordheim A, Lamkemeyer T, Madlung J, Hochholdinger F, Fowler JE, et al. An exocyst complex functions in plant cell growth in Arabidopsis and tobacco. The Plant cell. 2008;20:1330–1345. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Boyd L, Seydoux G. Stabilization of cell polarity by the C. elegans RING protein PAR-2. Developmental cell. 2006;10:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazak O, Bloch D, Poraty L, Sternberg H, Zhang J, Friml J, Yalovsky S. A rho scaffold integrates the secretory system with feedback mechanisms in regulation of auxin distribution. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Vidali L, Cheung AY. Polarized cell growth in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:159–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Zago MK, Abas L, van Marion A, Galvan-Ampudia CS, Offringa R. Phosphorylation of conserved PIN motifs directs Arabidopsis PIN1 polarity and auxin transport. The Plant cell. 2010;22:1129–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JB, Liu H, Chen M, Li X, Wang M, Yang Y, Wang C, Huang J, Liu G, Liu Y, et al. ROP3 GTPase Contributes to Polar Auxin Transport and Auxin Responses and Is Important for Embryogenesis and Seedling Growth in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2014 doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.127902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JA, Vejlupkova Z, Luo A, Meeley RB, Sylvester AW, Fowler JE, Smith LG. ROP GTPases act with the receptor-like protein PAN1 to polarize asymmetric cell division in maize. The Plant cell. 2011;23:2273–2284. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.085597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J-U, Vernoud V, Szumlanski A, Nielsen E, Yang Z. A Tip-Localized RhoGAP Controls Cell Polarity by Globally Inhibiting Rho GTPase at the Cell Apex. Current Biology. 2008;18:1907–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JU, Gu Y, Lee YJ, Yang Z. Oscillatory ROP GTPase activation leads the oscillatory polarized growth of pollen tubes. Molecular biology of the cell. 2005;16:5385–5399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JU, Wu G, Yan A, Lee YJ, Grierson CS, Yang Z. Pollen-tube tip growth requires a balance of lateral propagation and global inhibition of Rho-family GTPase activity. Journal of cell science. 2010;123:340–350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischebeck T, Stenzel I, Hempel F, Jin X, Mosblech A, Heilmann I. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate influences Nt-Rac5-mediated cell expansion in pollen tubes of Nicotiana tabacum. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology. 2011;65:453–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Palmer TM, Lukowitz W. The RWP-RK factor GROUNDED promotes embryonic polarity by facilitating YODA MAP kinase signaling. Current biology : CB. 2011;21:1268–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Raymond MJ, Yang Z, Smirnoff N. NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species formation required for root hair growth depends on ROP GTPase. Journal of experimental botany. 2007;58:1261–1270. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Shen JJ, Fu Y, Li H, Yang Z, Grierson CS. The Arabidopsis Rop2 GTPase is a positive regulator of both root hair initiation and tip growth. The Plant cell. 2002;14:763–776. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania U, Fendrych M, Friml J. Polar delivery in plants; commonalities and differences to animal epithelial cells. Open biology. 2014;4:140017. doi: 10.1098/rsob.140017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaothien P, Ok SH, Shuai B, Wengier D, Cotter R, Kelley D, Kiriakopolos S, Muschietti J, McCormick S. Kinase partner protein interacts with the LePRK1 and LePRK2 receptor kinases and plays a role in polarized pollen tube growth. Plant J. 2005;42:492–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H, Nakajima R, Iwano M, Kanaoka MM, Kimura S, Takeda S, Kawarazaki T, Senzaki E, Hamamura Y, Higashiyama T, et al. Ca2+-activated reactive oxygen species production by Arabidopsis RbohH and RbohJ is essential for proper pollen tube tip growth. The Plant cell. 2014;26:1069–1080. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.120642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U, Becker C, Schmitt AC, Kost B. Nt-RhoGDI2 regulates Rac/Rop signaling and polar cell growth in tobacco pollen tubes. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology. 2006;46:1018–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosami K, Ohki I, Nagano M, Furuita K, Sugiki T, Kawano Y, Kawasaki T, Fujiwara T, Nakagawa A, Shimamoto K, et al. The Crystal Structure of the Plant Small GTPase OsRac1 Reveals Its Mode of Binding to NADPH Oxidase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:28569–28578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn MP, Klopfenstein DR, Fischer N, Wodarz A. Membrane targeting of Bazooka/PAR-3 is mediated by direct binding to phosphoinositide lipids. Current biology : CB. 2010;20:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf DL. Induction of Polarity in Fucoid Zygotes. The Plant cell. 1997;9:1011–1020. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf DL, Bisgrove SR, Hable WE. Cytoskeletal control of polar growth in plant cells. Current opinion in cell biology. 1998;10:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau OS, Davies KA, Chang J, Adrian J, Rowe MH, Ballenger CE, Bergmann DC. Direct roles of SPEECHLESS in the specification of stomatal self-renewing cells. Science. 2014;345:1605–1609. doi: 10.1126/science.1256888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavy M, Bloch D, Hazak O, Gutman I, Poraty L, Sorek N, Sternberg H, Yalovsky S. A Novel ROP/RAC effector links cell polarity, root-meristem maintenance, and vesicle trafficking. Current biology : CB. 2007;17:947–952. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Szumlanski A, Nielsen E, Yang Z. Rho-GTPase-dependent filamentous actin dynamics coordinate vesicle targeting and exocytosis during tip growth. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;181:1155–1168. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lin Y, Heath RM, Zhu MX, Yang Z. Control of pollen tube tip growth by a Rop GTPase-dependent pathway that leads to tip-localized calcium influx. The Plant cell. 1999;11:1731–1742. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wu G, Ware D, Davis KR, Yang Z. Arabidopsis Rho-related GTPases: differential gene expression in pollen and polar localization in fission yeast. Plant physiology. 1998;118:407–417. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Cao L, Zhou Z, Zhu L, Ehrhardt D, Yang Z, Fu Y. Rho GTPase signaling activates microtubule severing to promote microtubule ordering in Arabidopsis. Current biology : CB. 2013;23:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Nagawa S, Chen J, Cao L, Chen X, Xu T, Li H, Dhonukshe P, Yamamuro C, Friml J, et al. A ROP GTPase-dependent auxin signaling pathway regulates the subcellular distribution of PIN2 in Arabidopsis roots. Current biology : CB. 2012;22:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Ren H, Fu Y. ROP GTPase-mediated auxin signaling regulates pavement cell interdigitation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of integrative plant biology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jipb.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Fuji RN, Yang W, Cerione RA. RhoGDI is required for Cdc42-mediated cellular transformation. Current biology : CB. 2003;13:1469–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowitz W, Roeder A, Parmenter D, Somerville C. A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2004;116:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlister CA, Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC. Transcription factor control of asymmetric cell divisions that establish the stomatal lineage. Nature. 2007;445:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nature05491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao G, Meng X, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhang S. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2011;23:1639–1653. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J. Local interactions shape plant cells. Current opinion in cell biology. 2006;18:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Chua NH. Microtubule stabilization leads to growth reorientation in Arabidopsis trichomes. The Plant cell. 2000;12:465–477. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni C, Zarov P, Rambourg A, Mann C. The SLT2 (MPK1) MAP kinase homolog is involved in polarized cell growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of cell biology. 1993;123:1821–1833. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:517–533. doi: 10.1038/nrm3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michniewicz M, Zago MK, Abas L, Weijers D, Schweighofer A, Meskiene I, Heisler MG, Ohno C, Zhang J, Huang F, et al. Antagonistic regulation of PIN phosphorylation by PP2A and PINOID directs auxin flux. Cell. 2007;130:1044–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Berkowitz G. Hydrogen peroxide, a messenger with too many roles? Redox report : communications in free radical research. 2001;6:69–72. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk AJ, Bischoff F, Rajendrakumar CS, Friml J, Braun M, Gilroy S, Palme K. Arabidopsis thaliana Rop GTPases are localized to tips of root hairs and control polar growth. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:2779–2788. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Messerli MA, Gilroy S. Imaging of the Yellow Cameleon 3.6 indicator reveals that elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ follow oscillating increases in growth in root hairs of Arabidopsis. Plant physiology. 2008;147:1690–1698. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro D, Castanho Coelho P, Rodrigues C, Camacho L, Quader H, Malho R. Modulation of endocytosis in pollen tube growth by phosphoinositides and phospholipids. Protoplasma. 2005;226:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s00709-005-0102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravcevic K, Mendrola JM, Schmitz KR, Wang YH, Slochower D, Janmey PA, Lemmon MA. Kinase associated-1 domains drive MARK/PAR1 kinases to membrane targets by binding acidic phospholipids. Cell. 2010;143:966–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima-Kawashima M, Kosik KS. The pool of map kinase associated with microtubules is small but constitutively active. Molecular biology of the cell. 1996;7:893–905. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Beck M, Mettbach U, Komis G, Hause G, Menzel D, Samaj J. Arabidopsis MPK6 is involved in cell division plane control during early root development, and localizes to the pre-prophase band, phragmoplast, trans-Golgi network and plasma membrane. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology. 2010;61:234–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AS, Peer WA. Vesicle trafficking: ROP-RIC roundabout. Current biology : CB. 2012;22:R576–R578. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch A, Cohen D, Kreitzer G, Rodriguez-Boulan E. cdc42 regulates the exit of apical and basolateral proteins from the trans-Golgi network. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:2171–2179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C, Romanowsky SM, Barron YD, Garg S, Azuse CL, Curran A, Davis RM, Hatton J, Harmon AC, Harper JF. Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate polarized tip growth in pollen tubes. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology. 2009;59:528–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagawa S, Xu T, Lin D, Dhonukshe P, Zhang X, Friml J, Scheres B, Fu Y, Yang Z. ROP GTPase-dependent actin microfilaments promote PIN1 polarization by localized inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis. PLoS biology. 2012;10:e1001299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagawa S, Xu T, Yang Z. RHO GTPase in plants: Conservation and invention of regulators and effectors. Small GTPases. 2010;1:78–88. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.1.2.14544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama R, Soyano T, Ishikawa M, Araki S, Tanaka H, Asada T, Irie K, Ito M, Terada M, Banno H, et al. Expansion of the cell plate in plant cytokinesis requires a kinesin-like protein/MAPKKK complex. Cell. 2002;109:87–99. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Fukuda H. Initiation of cell wall pattern by a Rho- and microtubule-driven symmetry breaking. Science. 2012;337:1333–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1222597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando K, Guo W. Membrane organization and dynamics in cell polarity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009;1:a001321. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petricka JJ, Van Norman JM, Benfey PN. Symmetry breaking in plants: molecular mechanisms regulating asymmetric cell divisions in Arabidopsis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009;1:a000497. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett-Heaps JD, Northcote DH. Organization of microtubules and endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis and cytokinesis in wheat meristems. Journal of cell science. 1966;1:109–120. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson ES, Miller DD, Callaham DA, van Aken J, Hackett G, Hepler PK. Tip-localized calcium entry fluctuates during pollen tube growth. Developmental biology. 1996;174:160–173. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri LJ, Peterson KM, Horst RJ, Torii KU. Molecular profiling of stomatal meristemoids reveals new component of asymmetric cell division and commonalities among stem cell populations in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2011;23:3260–3275. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potocky M, Jones MA, Bezvoda R, Smirnoff N, Zarsky V. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase are involved in pollen tube growth. The New phytologist. 2007;174:742–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]