Abstract

Introduction

HPV attributable cancers are the second most common infection-related cancers worldwide, with much higher burden in less developed regions. There are currently no country-specific estimates of the burden of these cancers in Nigeria just like many other low and middle income countries.

Methods

In this study, we quantified the proportion of the cancer burden in Nigeria that is attributable to HPV infection from 2012 to 2014 using HPV prevalence estimated from previous studies and data from two population based cancer registries (PBCR) in Nigeria. We considered cancer sites for which there is strong evidence of an association with HPV infection based on the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classification. We obtained age and sex-specific estimates of incident cancers and using the World Standard Population, we derived age standardized incidence (ASR) rates for each cancer type by categories of sex, and estimated the population attributable fractions (PAF).

Results

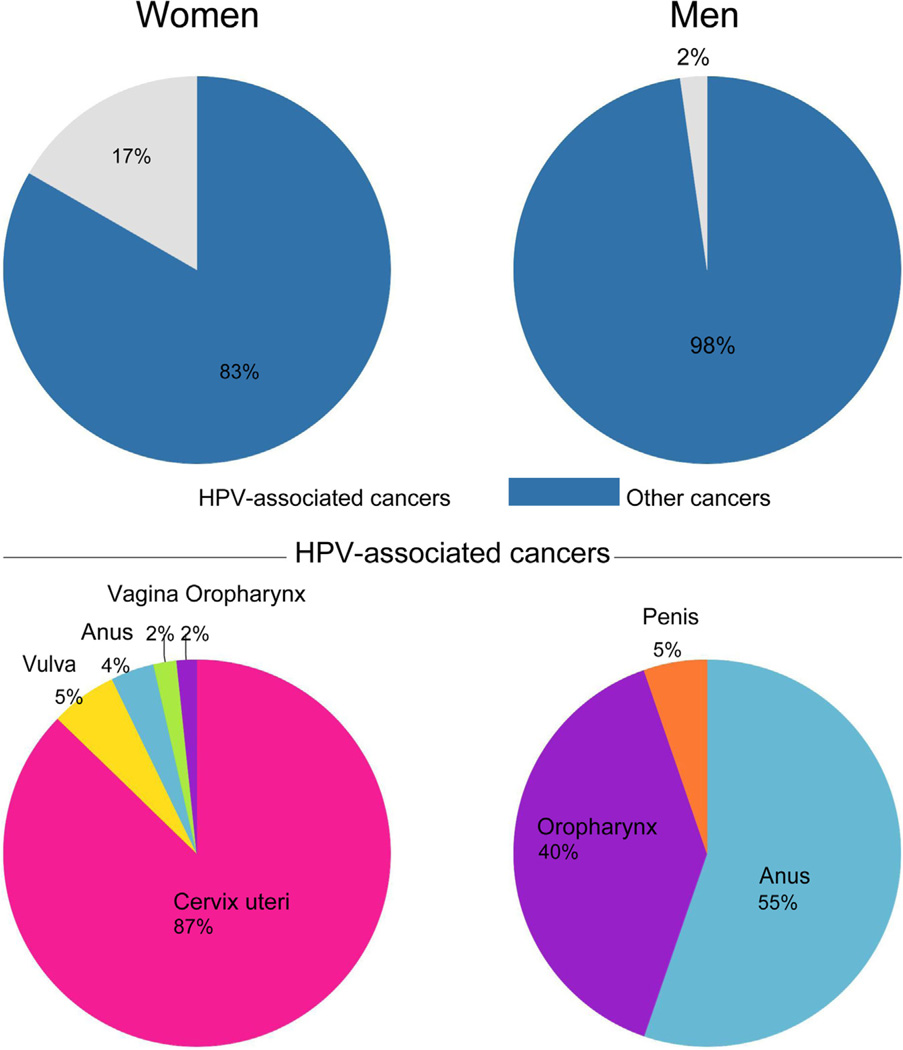

The two PBCR reported 4336 new cancer cases from 2012 to 2014. Of these, 1627 (37.5%) were in males and 2709 (62.5%) in females. Some 11% (488/4336) of these cancers were HPV associated; 2% (38/1627) in men and 17% (450/2709) in women. Of the HPV associated cancers, 7.8% occurred in men and 92.2% in women. The ASRs for HPV associated cancers was 33.5 per 100,000; 2.3 and 31.2 per 100,000 in men and women respectively. The proportion of all cancers attributable to HPV infection ranged from 10.2 to 10.4% (442–453 of 4336) while the proportion of HPV associated cancers attributable to HPV infection ranged from 90.6% to 92.8% (442–453 of the 488 cases). In men, 55.3% to 68.4% of HPV associated cancers were attributable to HPV infection compared to 93.6% to 94.8% in women. The combined ASR for HPV attributable cancers ranged from 31.0 to 31.7 per 100,000. This was 1.4 to 1.7 per 100,000 in men and 29.6 to 30.0 per 100,000 in women. In women, cervical cancer (n = 392, ASR 28.3 per 100,000) was the commonest HPV attributable cancer, while anal cancer (n = 21, ASR 1.2 per 100,000) was the commonest in men.

Conclusions

HPV attributable cancers constitute a substantial cancer burden in Nigerian women, much less so in men. A significant proportion of cancers in Nigerian women would be prevented if strategies such as HPV DNA based screening and HPV vaccination are implemented.

Keywords: HPV, HPV associated cancers, Cancer registries, Cancer incidence, Nigeria

1. Introduction

Approximately 2 million (16%) of all new cancer cases that develop globally every year are attributable to infections but the proportion differs significantly between developed and developing countries. In developed countries, infections-attributable cancers account for 3.3% while they account for 32.7% of annual incident cancer cases in developing countries [1]. Close to 5% of global incident cancers are attributable to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections and the proportions differ comparing developed (2.1%) to developing countries (14.2%) [2,3]. The human papilloma virus is the second largest contributor to infections associated cancers worldwide after Helicobacter Pylori, with a much higher burden in less developed regions [2]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer [4] (IARC) and a wide range of other public health organizations [5–7] consider that there is strong evidence for a causal relationship between HPV infection and cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, oral cavity, oropharynx and tonsils [8].

The population attributable fraction (PAF) which is the proportional reduction in disease incidence and mortality that would occur in a specific population if exposure to a risk factor is prevented, for HPV and cancer varies widely [9,2]. In 2008, the highest PAFs for HPV infection and cancer were for India (15.5%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (14.2%) while the lowest PAFs were for North America (1.6%) and Australia/New Zealand (1.2%) [2]. In the reference paper on global estimates of cancer disease burden, the PAF for Sub-Saharan Africa was computed using global HPV prevalence estimates and cancer registry data from GLOBOCAN 2012 to which only one population-based cancer registry (PBCR) in Nigeria contributed [10]. Currently, there are no country-specific estimates for the burden of HPV associated cancers in Nigeria.

In this study we quantify the proportion of the cancer burden in Nigeria that is attributable to HPV infection for the period 2012 to 2014 using HPV prevalence estimates derived from meta-analyses [11–15] and data from Nigerian PBCR. Knowledge of the proportion of the cancers that can be prevented by reducing the prevalence of HPV infections provides a critical baseline for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and contribute to analyses of the added value of such interventions [16]. HPV vaccinations, for example, will substantially reduce the burden of HPV associated diseases [17]. However many low and middle income countries, including Nigeria, are yet to implement HPV vaccination and HPV DNA test based screening programs [18].

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

We retrieved data on cancer incidence from two out of six PBCR in Nigeria, the Abuja and Enugu cancer registries for the period 2012 to 2014 because only these 2 registries submitted data to the Nigerian National System of Cancer Registries (NSCR) during the period under consideration [19]. We obtained age and sex-specific estimates of new cancer cases reported for the time period under review.

The Abuja Cancer Registry (ABCR) at the National Hospital Abuja started as a hospital-based cancer registry (HBCR) in 2005 but with support from NSCR became a PBCR in 2009. The registry covers a defined population of 1,406,239 people. The method of case ascertainment in the Abuja cancer registry has been described elsewhere [20]. The Enugu Cancer Registry (ECR) in the Oncology Department of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Ituku Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria began in 1988 as a HBCR but was developed into a PBCR by the NSCR in 2012. The registry covers a population of 1,103,153. These 2 registries cover a combined population of 2,509,392. Both registries use ICD-O-3 for coding and classification of cancers. While the ECR uses CanReg5 software for data entry, processing and storage, ABCR uses CanReg4.

The data were checked and cleaned prior to analysis by two of the authors (EJA and MO). Quality control checks were performed using IARC’s CanReg5 software to ensure uniformity, correctness of coding and completeness of information, including removal of duplicates. Information on cancer sites for which there is strong evidence of an association with HPV infection was based on the IARC Monograph 100b [8], a comprehensive review of published information on infectious agents that may be carcinogenic to humans [3]. The cancer sites (ICD-O code) considered in this study were; Cervix (C.53), Vulva (C.51), Vagina (C.52), Anus (C. 21), Penis (C.60) and Oropahrynx (C.01, C.09, C10). Incidence cases by year, sex and 5-year age group for the above cancers, were extracted from the cleaned cancer registries’ databases.

2.2. Statistical analyses

We calculated age standardized incidence rates by cancer type and sex using the direct method based on the WHO World Standard Population. We obtained PAF estimates from previous studies published in the literature (Table 1). We did not use methods that require population prevalence estimates of HPV and relative risks given the absence of large population based surveys of cancer-specific HPV infection sites in Nigeria and few epidemiologic studies with relative risk estimates for the different cancers. Instead, we searched PubMed and found 34 studies of HPV prevalence from Africa with sample sizes greater than 50. Our search strategy included the following terms: Human papilloma-virus OR HPV and cancer* OR tumour* OR tumor* OR malignan* OR neoplas* OR carcinoma* OR adenocarcinoma* OR precancer* OR pre-cancer* OR dysplas* and (genital infection) OR cervix OR vagina OR vulva OR anus OR oropharynx OR penis and SSA OR SubSaharan Africa OR Sub Saharan Africa OR West Africa OR East Africa OR North Africa OR Central Africa OR South Africa and prevalence.

Table 1.

Previous HPV Prevalence studies in African populations.

| Cancer Site | ICD-O Code | Regionala prevalence of HPV in cancers (African populations) |

Studies in African populations (Sample size) [Source] |

PAF estimates used in this study% [Source] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix | C.53 | 83%–99% | Nigeria (192), Ghana (167), South Africa (300)[58] Nigeria (75) [59] |

100 [11] |

| Vulva | C.51 | 100% | Botswana (35) [60] | 40 [12] |

| Vagina | C.52 | – | None | 40–70 [21,12] |

| Anus | C.21 | 62% | Nigeria, Mali, Senegal (13) [13] | 88–90 [21,13] |

| Oropharynx | C.01, C.09– C.10 |

19% | Ghana (78) [24] | 12–46 [15,21] |

| Penis | C.60 | 65%–68% | Uganda (17) [23], Kenya (22) [22] | 48 [14] |

Regional estimates are presented for countries in West Africa where available, or other African countries.

We used a PAF of 100% for cervical cancer, given that it is almost universally accepted that HPV is necessary for the development of the disease and that all cervical cancer cases can be attributed to HPV infection [11]. For vulvar cancer, we identified only one study in Africa; a study from Botswana which suggested an HPV prevalence of 100% among 35 cases of vulvar cancer. As a result of the small sample size and in the absence of other studies from Sub- Saharan Africa, we used a PAF of 40% for vulvar cancer based on meta-analyses [12]. We did not find any individual studies of HPV prevalence in anal cancer in Africa so we used a PAF range of 88% to 90% for anal cancer from two studies; a large intercontinental study than included cases from West Africa and a global study by Parkin et al. [13,21] We identified two studies from Uganda and Kenya that evaluated prevalence of HPV in penile cancer however, we used a PAF range of 40 to 48% from a meta-analysis, because of the limited sample sizes of 17 and 22 in the African studies [22,23,14]. We used a PAF range of 12 to 46% for oropharyngeal cancers [15,24]. The PAF estimates and their sources are provided in Table 1.

2.3. Sensitivity analyses

We obtained incidence estimates for cervical cancer from GLOBOCAN 2012 and used these to conduct sensitivity analyses in our study by comparing the ASR of HPV associated cervical cancer reported in GLOBOCAN 2012 with the findings from our analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

A total of 4336 cases of cancer were reported by the ABCR and ECR registries from 2012 to 2014 (Table 2). Among these, 1627 (37.5%) were in males and 2709 (62.5%) in females. Of the total cancers in both sexes, 488 (11%) were HPV associated and most of these occurred in women (92.2%, 450/488) compared to men (7.8%, 38/488). (Table 2) HPV associated cancers constituted 2% (38/1627) of all cancers in men and 17% (450/2709) of all cancers in women. (Fig. 1) The combined ASR for HPV associated cancers was 33.5 per 100,000 and it was 2.3 and 31.2 per 100,000 in men and women respectively. The proportion of the total cancers attributable to HPV infection ranged from 10.2 to 10.4% (442 to 453 of 4336) while the HPV associated cancers that were attributable to HPV infection ranged from 90.6 to 92.8% (442 to 453 of 488). In men, 55.3 to 68.4% (21 to 26 of 38) HPV associated cancers were attributable to HPV infection while in women 93.6% to 94.9% (421 to 427 of 450) HPV associated cancers were attributable to HPV infection (Table 3). The ASR for HPV attributable infections ranged from 31.0 to 31.7 per 100,000 and this was 1.4 to 1.7 per 100,000 in men and 29.6 to 30.0 per 100,000 in women (Table 3).

Table 2.

Total number of cancer cases and number of HPV associated cancers in 2012–2014 by cancer registry site.

| Sex | All cancers (2012–2014) | Total HPV associated cancers | Number and percentages of HPV associated cancers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix (%) | Vulva (%) | Vagina (%) | Anus (%) | Oropharynx (%) | Penis (%) |

|||

| Female | 2709 (100) | 450 (16.6) | 392 (14.5) | 25 (1) | 8 (0.3) | 17 (0.6) | 8 (0.3) | – |

| Female | 1627 (100) | 38 (2.3) | – | – | – | 21 (1.3) | 15 (0.9) | 2 (0.1) |

| 4336 (100) | 488 (11.3) | 392 (9) | 25 (0.6) | 8 (0.2) | 38 (0.9) | 23 (0.5) | 2 (0.04) | |

Fig. 1.

Total cancers and total HPV associated cancers reported by gender, in two regions in Nigeria from 2012–2014.

Table 3.

Age standardised incidence rates of HPV associated cancers and cancers attributable to HPV in two regions in Nigeria, 2012–2014.

| Sex | Cancer Site | ICD-O Code | Total no of cancers |

ASRHPV Associated cancers |

Total no of cancers attributable to HPV |

Population attributable Fraction (PAF) % |

ASR HPV Attributable cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Cervix | C.53 | 392 | 28.3 | 100 | 392 | 28.3 |

| Vulva | C.51 | 25 | 1.3 | 40 | 10 | 0.5 | |

| Vagina | C.52 | 8 | 0.4 | 40–70 | 3–6 | 0.2–0.3 | |

| Anus | C.21 | 17 | 0.7 | 88–90 | 15 | 0.6 | |

| Oropharynx | C.01, C.09– C.10 |

8 | 0.5 | 12–46 | 1–4 | 0–0.3 | |

| Total Female | 450 | 31.2 | – | 421–427 | 29.6–30.0 | ||

| Male | Penis | C.60 | 2 | 0.1 | 40–48 | 1 | 0.05 |

| Anus | C.21 | 21 | 1.4 | 88–90 | 18 | 1.2 | |

| Oropharynx | C.01, C.09–C.10 | 15 | 0.8 | 12–46 | 2–7 | 0.1–0.4 | |

| Total male | 38 | 2.3 | 21–26 | 1.4–1.7 | |||

| Total both sexes | 488 | 33.5 | 442–453 | 31–31.7 | |||

3.2. Cervical cancer

Some 392 cases of cervical cancer were reported by the two PBCR during this period. Cervical cancer was the most common HPV associated cancer overall and in women in this population (Fig. 1), with ASR of 28.3 per 100,000. Given a PAF of 100% for cervical cancer, all 392 cases reported by the registries are attributable to HPV infection (Table 3) so the ASR for HPV attributable cervical cancer in this population is 28.3 per 100,000

3.3. Oropharyngeal cancers

There were 23 cases of oropharyngeal cancer reported in both sexes by the registries. Of these, 15 (65.2%) occurred in men and 8 (34.7%) in women. The ASR for HPV associated oropharyngeal cancer was 0.8 per 100,000 in men and 0.5 per 100,000 in women. We used a PAF range of 12% to 46% [21,15] and estimated that 3 to 11 of the 23 cases of oropharyngeal cancer were attributable to HPV infection (Table 3). The ASR for HPV attributable oropharyngeal cancers ranged from 0.1 to 0.4 per 100,000 in men and 0 to 0.3 per 100,000 in women (Table 3).

3.4. Anal cancer

Some 38 cases of anal cancer were reported with 21 (55.3%) cases in men and 17 (44.7%) cases in females. The ASR for HPV associated anal cancer was 2.1 per 100,000. Using a PAF of 88% to 90% for anal cancer, we estimated that 33 of the 38 cases of anal cancer in both sexes were attributable to HPV infection (Table 3). The ASR for HPV attributable anal cancer in this population was 1.8 per 100,000. In men, anal cancer was the most common HPV attributable cancer with ASR of 1.2 per 100,000. In women, anal cancer was the third most common HPV attributable cancer after cervical and vulval cancers with an ASR of 0.6 per 100,000.

3.5. Vulvo-vaginal cancers

The registries reported 33 cases of vulvo-vaginal cancer from 2012 to 2014. Of these, 25 were vulva cancers and the ASR for HPV associated vulval cancer in this population was 1.3 per 100,000. We used a PAF of 40% from meta-analysis studies to compute attributable risk [12]. Therefore 10 of the 25 cases of vulva cancer were attributable to HPV infection. The ASR for HPV attributable vulval cancers was 0.5 per 100,000.

Only 8 cases of vaginal cancer were reported during the time period under review and of these, 6 cases were attributable to HPV infection based on PAF estimates of 70% from a meta-analysis by De Vuyst et al. [12]. The ASR for HPV associated vaginal cancers was 0.4 per 100,000 and the ASR for HPV attributable vaginal cancers ranged from 0.2 to 0.3 per 100,000.

3.6. Penile cancers

There were only two cases of penile cancer reported by the cancer registries giving an ASR for HPV associated penile cancer of 0.1 per 100,000 and HPV attributable penile cancer of 0.05 per 100,000.

3.7. Sensitivity analyses

We compared our findings to the GLOBOCAN 2012 database of IARC. The ASR for HPV associated and HPV attributable cervical cancer reported in GLOBOCAN was 29 per 100,000. This result is similar to our findings of 28.3 per 100,000 for the ASR for HPV associated and HPV attributable cervical cancer in Nigeria.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that Nigerian women had a higher burden of HPV attributable cancers compared to men, due to high incidence of cervical cancer. We found that 10.2 to 10.4% of all cancers and 90.6 to 92.8% of HPV associated cancers were attributable to HPV infection. The proportion of HPV attributable cancers in Nigeria is similar to findings from other developing countries [25] but much higher than in developed countries [26] mainly due to the higher burden of cervical cancer in Nigeria.

Cervical cancer was the most common HPV attributable cancer in our study. Similar incidence rates to our findings have been reported in West-Africa (29.3 per 100,000) and Central Africa (28 per 100,000) but the incidence rates in South Africa (38.2 per 100,000) and Eastern Africa (42.7 per 100,000) were much higher [27]. This is in contrast with developed regions such as Europe were much lower incidence rates (11.9 per 100,000) have been reported [27]. This difference with the developed world may be as a result of differences in the prevalence of risk factors for cervical cancer such as early age at first intercourse [28], total number of lifetime sexual partners, sexual practices [29], and early age at first pregnancy [28]. The widespread availability of population based screening programs for cervical cancer in developed countries has also contributed to reduced incidence while HIV infection in Africa is contributing to increased incidence [30,31].

Analysis of worldwide trends showed that the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers significantly increased between 1983 and 2002 in several countries around the world [32] Given that countries with reduced or stable incidence of lung cancer had increased incidence of oropharyngeal cancer, Chaturverdi et al. [32]. surmised that the increase in oropharyngeal cancer incidence in developed countries was due to factors other than smoking, notably HPV infection. HPV16 was shown to account for the vast majority (~95%) of HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas [33].

Our results showed than the incidence of HPV attributable oropharyngeal cancers is low in Nigerian men and women at this time. There is no data on time trends of oropharyngeal cancers, for most developing countries. A recent study of head and neck cancers from Nigeria analyzed blocks from 123 patients and did not find any to be positive for HPVHPV associated [34]. Oropharyngeal cancers were the second most common HPV attributable cancers in men after anal cancers, but were the least common HPV attributable cancers in women. The low prevalence of HPV attributable oropharyngeal cancers in Nigerian adults may be related to low prevalence of sexual behaviors that may be contributing to rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer in other populations [35,36]. The gender difference that we observed in incident oropharyngeal cancers in our study may be due to lower prevalence of use of tobacco products and alcohol among women compared to men in the Nigeria. Other risk factors for oropharyngeal cancer are HIV infection [37], poor oral hygiene [38], diet [39,40] and occupational [41] exposures.

For the past three decades, the global incidence of anal cancer has been rising by about 2% per year among both men and women [42]. The increasing incidence of anal cancer may reflect changes in sexual behavior in the second half of the twentieth century that increases the risk of exposure to HPV in the anal canal [43]. In contrast to reports from other parts of the world where the incidence of anal cancers is higher in women, we found almost similar incidence in both sexes [44–47]. The ASR of anal cancer in our study was 1.4 and 0.7 per 100,000 in men and women respectively. Similarly low incidence rates have been reported in Uganda 0.2 per 100,000 in men and women and <0.1 per 100,000 in men and women in Zimbabwe [25]. Risk factors for anal cancers include chronic irritation in the form of fissures or fistulas, smoking and immunosuppression [43].

Vulvar and vaginal cancers are rare malignancies of the female genital tract. Worldwide, about 2% and 1.5% of the cancers attributable to HPV in 2008 were cancers of the vulva and vagina, respectively [12]. Although there are no previous studies in Nigeria reporting the incidence of vulva cancer, the incidence of vulva cancer in our study was similar to the results from previous studies conducted in Uganda and Zimbabwe [25]. The incidence of vaginal cancer was also very similar to findings from other African countries of 0.4 and 0.7 per 100,000 in Uganda and Zimbabwe respectively [25]. The risk factors for vulvo-vaginal cancers are multiple lifetime sexual partners, age at first intercourse, immunosuppression, cigarette smoking, chronic pessary use, surgical menopause, or prior hysterectomy [48,49]; however these factors have not been examined in relation to vulvo-vaginal cancers among Nigerian women, to the best of our knowledge. A study conducted in Nigeria about 25 years ago showed that vulvar carcinoma was more common among women of low socio-economic status [50].

A review of 31 studies on HPV and penile cancer revealed that about 50% of the cancers were associated with HPV 16 and 18 [51]. Although penile HPV prevalence is high, persistence is less likely [52], thus HPV is not a necessary cause of penile cancer. Penile cancer virtually occurs in only uncircumcised men. In Israel, where most males are circumcised during the neonatal period, the rate of penile cancer is as low as 1 case per one million person-years [53], whereas in Brazil where most men are uncircumcised, the rates are higher and penile cancer accounts for 2–5% of male cancers [54]. The low ASR of penile cancer estimated in this study may be due to high prevalence of neonatal circumcision in Nigeria. Our findings of low incidence of penile cancer are similar to reports from other Sub-Saharan African countries [25].

The prevalence of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa has been linked to several HPV attributable cancers. Several studies in Nigeria have found an association between cervical cancer and HIV [47,55]. A registry linkage study in Nigeria reported a twofold higher risk of cervical cancer in people living with HIV/AIDS [31]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed an excess risk of anal cancer among men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly among those who were HIV positive [56]. Other HPV attributable cancers such as oropharyngeal cancers have also been linked with HIV infection [37]. More effective HIV/AIDS control interventions in developing countries may reduce the incidence of HPV attributable cancers particularly cervical cancer [27].

Our study has several important limitations. Studies of the prevalence of HPV infection in Africa are few, often have small sample sizes and lacked methodological rigor. Therefore, the prevalence measured may not be entirely representative of the population. In this study, we mostly used prevalence estimates derived from meta-analyses and provided a range of values for the attributable fractions in a bid to obtain more representative results. Secondly, this data was from only two of the six PBCR in Nigeria that had data for the period under study and this may limit the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility of problems with completeness and representativeness of the cancer registration data based on the two catchment populations. However our sensitivity analyses showed that the ASR of cervical cancer in our study of 28.3 per 100,000 is very similar to the national estimate for Nigeria (29 per 100,000) as reported in GLOBOCAN 2012 [57].

5. Conclusion

This is the first study to provide information on the incidence of HPV associated and HPV attributable cancers in Nigeria. The estimate of HPV attributable cancers in our study is substantial and approximately 90% of these cancers would be prevented if HPV infection in this population is prevented through screening and prophylactic vaccination. Our findings would inform public health policy on the potential impact of HPV prevention and for examining future trends in HPV attributable cancers in Nigeria.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work in data collection and data entry carried out by the cancer registrars at the Abuja and Enugu population-based cancer registries. This work was supported by IHV-UM Capacity Development for Research into AIDS-Associated Malignancies (CADRE, NIH/NCI D43CA153792) and the African Collaborative Center for Microbiome and Genomics Research (ACCME, NIH/NHGRI U54HG006947).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions

EJA, EOD, SNA, MO and EAO all contributed equally to this manuscript; by contributing to the concept and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript and approving the final version for submission. FI, TO, EE, RA contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data, providing revisions to the manuscript and approving the final version of the manuscript. FB took part in the analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approving the final version to be submitted. CAA obtained funding, conceived the study and study design, provided critical revisions for intellectual content and guided all aspects of the paper.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Franceschi S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2016;4(9):e609–e616. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607–615. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Plummer M, Franceschi S. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl. 5):F12–F23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IARC. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 100. A Review of Carcinogen—Part B: Biological Agents. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Cancers. [on Sept 26, 2016];2014 Jun 23; Accessed at www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm.

- 6.National Cancer Institute. HPV and Cancer. [on Sept 26, 2016];2015 Feb 19; Accessed at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/HPV.

- 7.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D, Cronin KA, Watson M, Schiffman M, Henley SJ, Schymura MJ, Anderson RN, Yankey D, Edwards BK. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus(HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105(3):175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V. Group WHOIAfRoCMW, A review of human carcinogens—part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):321–322. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Metrics: Population Attributable Fraction (PAF) [Accessed 17/07/2015]; http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/metrics_paf/en/

- 10.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12:AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;124(7):1626–1636. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24116. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alemany L, Saunier M, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Quiros B, Salmeron J, Shin HR, Pirog EC, Guimera N, Hernandez-Suarez G, Felix A, Clavero O, Lloveras B, Kasamatsu E, Goodman MT, Hernandez BY, Laco J, Tinoco L, Geraets DT, Lynch CF, Mandys V, Poljak M, Jach R, Verge J, Clavel C, Ndiaye C, Klaustermeier J, Cubilla A, Castellsague X, Bravo IG, Pawlita M, Quint WG, Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S H.V.S. Group. Human papillomavirus DNA prevalence and type distribution in anal carcinomas worldwide. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28963. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backes DM, Kurman RJ, Pimenta JM, Smith JS. Systematic review of human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive penile cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(4):449–457. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9276-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10552-008-9276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, Arbyn M, Castellsague X, Laporte L, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Trottier H. HPV DNA E6/E7 mRNA, and p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70471-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-204 5(14)70471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoste G, Vossaert K, Poppe WA. The clinical role of HPV testing in primary and secondary cervical cancer screening. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013;2013:610373. doi: 10.1155/2013/610373. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/610373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burger EA, Lee K, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, Chesson HW, Markowitz LE, Kim JJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in human papillomavirus-associated cancer burden with first-generation and second-generation human papillomavirus vaccines. Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cncr.30007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruni L, B-RL, Albero G, Aldea M, Serrano B, Valencia S, Brotons M, Mena M, Cosano, MJR, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre) Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Nigeria. Summary Report 2015-03-20. Available from: http://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/NGA.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jedy-Agba EE, Oga EA, Odutola M, Abdullahi YM, Popoola A, Achara P, Afolayan E, Banjo AA, Ekanem IO, Erinomo O, Ezeome E, Igbinoba F, Obiorah C, Ogunbiyi O, Omonisi A, Osime C, Ukah C, Osinubi P, Hassan R, Blattner W, Dakum P, Adebamowo CA. Developing national cancer registration in developing countries—case study of the nigerian national system of cancer registries. Front. Public Health. 2015;3:186. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00186. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.20 15.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jedy-Agba E, Curado MP, Ogunbiyi O, Oga E, Fabowale T, Igbinoba F, Osubor G, Otu T, Kumai H, Koechlin A, Osinubi P, Dakum P, Blattner W, Adebamowo CA. Cancer incidence in Nigeria: a report from population-based cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(5):e271–e278. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.04.007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the y ear 2002. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118(12):3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senba M, Buziba N, Mori N, Wada A, Irie S, Toriyama K. Detection of Human papilloma virus and cellular regulators p16INK4a, p53, and NF-kappaB in penile cancer cases in Kenya. Acta Virol. 2009;53(1):43–48. doi: 10.4149/av_2009_01_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tornesello ML, Duraturo ML, Guida V, Losito S, Botti G, Pilotti S, Stefanon B, De Palo G, Buonaguro L, Buonaguro FM. Analysis of TP53 codon 72 polymorphism in HPV-positive and HPV-negative penile carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(1):159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.027. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaba G, Dzudzor B, Gyasi RK, Asmah RH, Brown CA, Kudzi W, Wiredu EK. Human papillomavirus genotypes in a subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. W. Afr. J. Med. 2014;33(2):121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vuyst H, Alemany L, Lacey C, Chibwesha CJ, Sahasrabuddhe V, Banura C, Denny L, Parham GP. The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in sub-saharan Africa. Vaccine. 2013;31(Suppl. 5):F32–F46. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.092. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Reducing HPV-associated cancer globally. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phil.) 2012;5(1):18–23. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0542. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louie KS, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P. Epidemiology and prevention of human papilloma virus and cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive review. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2009;14(10):1287–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02372.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makuza JD, Nsanzimana S, Muhimpundu MA, Pace LE, Ntaganira J, Riedel DJ. Prevalence and risk factors for cervical cancer and pre-cancerous lesions in Rwanda. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2015;22:26. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.22.26.7116. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.22.26.7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mbulaiteye SM, Bhatia K, Adebamowo C, Sasco AJ. HIV and cancer in Africa: mutual collaboration between HIV and cancer programs may provide timely research and public health data. Infect. Agents Cancer. 2011;6(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-6-16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacquet A, Odutola M, Ekouevi DK, Tanon A, Oga E, Kariyiare GB, Akakpo J, Charurat M, Zannou MD, Eholie SP, Sasco AJ, Bissagnene E, Adebamowo AC, Dabis F. The IeDEA west africa collaboration HIV and cancer in referral hospitals from four west african countries, the IeDEA west africa collaboration. 20th International AIDS Conference; Melbourne, Australia. July 20–25; International AIDS Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akarolo-Anthony SN, Maso LD, Igbinoba F, Mbulaiteye SM, Adebamowo CA. Cancer burden among HIV-positive persons in Nigeria: preliminary findings from the Nigerian AIDS-cancer match study. Infect. Agents Cancer. 2014;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Rosenberg PS, Bray F, Gillison ML. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(36):4550–4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirghani H, Amen F, Moreau F, Lacau St Guily J. Do high-risk human papilloma viruses cause oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma? Oral. Oncol. 2015;51(3):229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.011. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oga EA, Schumaker LM, Alabi BS, Obaseki D, Umana A, Bassey IA, Ebughe G, Oluwole O, Akeredolu T, Adebamowo SN, Dakum P, Cullen K, Adebamowo CA. Paucity of HPV-related head and neck cancers (HNC) in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152828. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chancellor JA, Ioannides SJ, Elwood JM. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer and the role of sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Commun. Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12255. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahlstrom KR, Bell D, Hanby D, Li G, Wang LE, Wei Q, Williams MD, Sturgis EM. Socioeconomic characteristics of patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma according to tumor HPV status, patient smoking status, and sexual behavior. Oral. Oncol. 2015;51(9):832–838. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.06.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370(9581):59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahrens W, Pohlabeln H, Foraita R, Nelis M, Lagiou P, Lagiou A, Bouchardy C, Slamova A, Schejbalova M, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Kjaerheim K, Agudo A, Castellsague X, Macfarlane TV, Macfarlane GJ, Lee YC, Talamini R, Barzan L, Canova C, Simonato L, Thomson P, McKinney PA, McMahon AD, Znaor A, Healy CM, McCartan BE, Metspalu A, Marron M, Hashibe M, Conway DI, Brennan P. Oral health, dental care and mouthwash associated with upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk in Europe: the ARCAGE study. Oral. Oncol. 2014;50(6):616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.03.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bravi F, Bosetti C, Filomeno M, Levi F, Garavello W, Galimberti S, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Foods, nutrients and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;109(11):2904–2910. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.667. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garavello W, Lucenteforte E, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. The role of foods and nutrients on oral and pharyngeal cancer risk. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(1–2):25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riechelmann H. Occupational exposure and cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx. Laryngorhinootologie. 2002;81(8):573–579. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33365. doi: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1055/s-2002-33365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson LG, Madeleine MM, Newcomer LM, Schwartz SM, Daling JR. Anal cancer incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results experience, 1973–2000. Cancer. 2004;101(2):281–288. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20364. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Burchell A, Albero G, Giuliano AR, Goodman MT, Kjaer SK, Palefsky J. Updating the natural history of human papillomavirus and anogenital cancers. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl. (5)):F24–F33. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.089. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ntombela XH, Sartorius B, Madiba TE, Govender P. The clinicopathologic spectrum of anal cancer in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: analysis of a provincial database South Africa. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(4):528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.05.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark MA, Hartley A, Geh JI. Cancer of the anal canal. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(3):149–157. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01410-X. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01410-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klas JV, Rothenberger DA, Wong WD, Madoff RD. Malignant tumors of the anal canal: the spectrum of disease, treatment, and outcomes. Cancer. 1999;85(8):1686–1693. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990415)85:8<1686::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaquet A, Odutola M, Ekouevi DK, Tanon A, Oga E, Akakpo J, Charurat M, Zannou MD, Eholie SP, Sasco AJ, Bissagnene E, Adebamowo C, Dabis F. Ie DEAWAc, Cancer and HIV infection in referral hospitals from four West African countries. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(6):1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.09.002. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Carter JJ, McKnight B, Porter PL, Galloway DA, McDougall JK, Tamimi H. A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002;84(2):263–270. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6502. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2001.6502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Matanoski G, Chen VW, Saraiya M, Coughlin SS, King JB, Tao XG. Descriptive epidemiology of vaginal cancer incidence and survival by race, ethnicity, and age in the United States. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2873–2882. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23757. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Briggs ND, Katchy KC. Pattern of primary gynecological malignancies as seen in a tertiary hospital situated in the Rivers State of Nigeria. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 1990;31(2):157–161. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(90)90714-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miralles-Guri C, Bruni L, Cubilla AL, Castellsague X, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in penile carcinoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009;62(10):870–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.063149. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2008.063149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bosch FX, Broker TR, Forman D, Moscicki AB, Gillison ML, Doorbar J, Stern PL, Stanley M, Arbyn M, Poljak M, Cuzick J, Castle PE, Schiller JT, Markowitz LE, Fisher WA, Canfell K, Denny LA, Franco EL, Steben M, Kane MA, Schiffman M, Meijer CJ, Sankaranarayanan R, Castellsague X, Kim JJ, Brotons M, Alemany L, Albero G, Diaz M, de Sanjose S authors of ICOMCCoHPVI, Related Diseases Vaccine Volume S. Comprehensive control of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases. Vaccine. 2013;31(Suppl 7):H1–H31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parkin DMWSL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. 2002;VIII [Google Scholar]

- 54.Favorito LA, Nardi AC, Ronalsa M, Zequi SC, Sampaio FJ, Glina S. Epidemiologic study on penile cancer in Brazil. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34(5):587–591. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000500007. discussion 591–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dim CC, Ezegwui HU, Ikeme AC, Nwagha UI, Onyedum CC. Prevalence of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions among HIV-positive women in Enugu, South-eastern Nigeria. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011;31(8):759–762. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.598967. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.598967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, Fairley CK, Farnsworth A, Garland SM, Hillman RJ, Petoumenos K, Roberts J, Tabrizi SN, Templeton DJ, Grulich AE. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):487–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.GLOBOCAN. Nigeria. [accessed 23rd March, 2016];2012 http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Denny L, Adewole I, Anorlu R, Dreyer G, Moodley M, Smith T, Snyman L, Wiredu E, Molijn A, Quint W, Ramakrishnan G, Schmidt J. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in invasive cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134(6):1389–1398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28425. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okolo C, Franceschi S, Adewole I, Thomas JO, Follen M, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Ibadan, Nigeria. Infect Agents Cancer. 2010;5(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-5-24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/1 0.1186/1750-9378-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tesfalul M, Simbiri K, Wheat CM, Motsepe D, Goldbach H, Armstrong K, Hudson K, Kayembe MK, Robertson E, Kovarik C. Oncogenic viral prevalence in invasive vulvar cancer specimens from human immunodeficiency virus-positive and −negative women in Botswana. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2014;24(4):758–765. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000111. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]