Abstract

Impulsive behavior is a common symptom in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, schizophrenia, drug abuse, smoking, obesity and compulsive gambling. Stable levels of impulsive choice have been found in humans and rats and a recent study reported significant test-retest reliability of impulsive choice behavior after 1 and 5 months in rats. Time-based behavioral interventions have been successful in decreasing impulsive choices. These interventions led to improvements in the ability to time and respond more appropriately to adventitious choices. The current study examined the use of a time-based intervention in experienced, middle-aged rats. This intervention utilized a variable interval schedule previously found to be successful in improving timing and decreasing impulsive choice. This study found that the intervention led to a decrease in impulsive choices and there was a significant correlation between the improvement in self-control and post-intervention temporal precision in middle-aged rats. Although there were no overall group difference in bisection performance, individual differences were observed, suggesting an improvement in timing. This is an important contribution to the field because previous studies have utilized only young rats and because previous research indicates a decrease in general timing abilities with age.

Keywords: self-control, delay discounting, intervention, timing, delay aversion, aging

Introduction

Impulsive behavior is a common symptom in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Neef et al. 2005), schizophrenia (Heerey et al. 2007), drug abuse (Bickel and Marsch 2001), smoking (Mitchell 1999), obesity (Weller et al. 2008; Boomhower, Rasmussen, and Doherty 2013), and compulsive gambling (Alessi and Petry 2003; Petry and Casarella 1999). Impulsive choice is typically measured in a paradigm that gives the subject the choice between a smaller reward received sooner (SS) or a larger reward received after a longer delay (LL). Stable levels of impulsive choice have been found in humans and rats (Jimura et al. 2011; Odum 2011; Peterson, Hill, and Kirkpatrick 2015; Marshall, Smith, and Kirkpatrick 2014; Galtress, Garcia, and Kirkpatrick 2012), and we recently reported significant test-retest reliability of impulsive choice behavior after 1 and 5 months in rats (Peterson, Hill, and Kirkpatrick 2015). Because levels of impulsive choice are generally stable over time, some researchers have suggested that it is a behavioral trait (Odum 2011, 2011).

Although impulsive choice behavior does appear to be a relatively stable trait, it is also somewhat malleable and can be altered through specific training. A number of behavioral interventions have been implemented to increase self-control through time-based techniques. Interval fading is the prominent method for training self-control in impulsive choice tasks. In this procedure, the LL delay is gradually increased (or the SS delay gradually decreased) over time. This method has resulted in improvements in self-control in pigeons and humans, evidenced by increased preference for the LL reinforcer (Dixon et al. 1998; Dixon and Holcomb 2000; Binder, Dixon, and Ghezzi 2000; Schweitzer and Sulzer-Azaroff 1995; Neef, Bicard, and Endo 2001; Dixon, Rehfeldt, and Randich 2003; Mazur and Logue 1978). Additionally, training with long delays (Stein et al. 2013; Stein et al. 2015) and training with both SS and LL delays leads to fewer SS choices in both children and rats (Smith, Marshall, and Kirkpatrick 2015; Eisenberger and Adornetto 1986).

One possible source of the intervention effects may be changes in timing processes. Smith et al. (2015) reported that the delay exposure resulted in increased timing precision during the impulsive choice task, suggesting that improvements in timing processes may have been the source of the delay intervention effects on impulsive choice. In a related vein, Marshall et al. (2014) found that rats that demonstrated greater timing precision in a temporal discrimination task chose the LL more often; these rats also demonstrated greater delay tolerance, indicating that timing precision, delay tolerance, and self-control co-occur. It thus appears that temporal discrimination and delay tolerance may be important gateways for understanding mechanisms of impulsive choice and for modifying impulsive choice (Kirkpatrick, Marshall, and Smith 2015; Peterson et al. 2015; Galtress, Garcia, and Kirkpatrick 2012; Wittmann and Paulus 2008; Bitsakou et al. 2009; McClure, Podos, and Richardson 2014; Zauberman et al. 2009).

Although impulsive choice is fairly stable over time, age-related changes have been observed. However, only a few studies have examined either timing or impulsive choice as a function of aging. Dellu-Hagedorn et al. (2004) found individual differences in impulsive choice behavior in a sample of young rats that remained stable at middle age, so that the most impulsive rats remained the most impulsive. However, the overall level of impulsive choice declined over time. Lejeune et al. (1998) found that four-month-old rats were better at accurately timing delays than older rats. Aged rats were consistently slower to respond than the younger rats, and the older rats took longer to adjust to the initial change in delay than the younger rats. Conversely, Simon and colleagues (2010) concluded that the decrease in impulsive choices observed in aged Fisher 344 rats was not due to insensitivity to delay because this group displayed only minimal differences in timing when compared to the young adult rats. It is evident that the relationship between timing mechanisms and impulsive choice behavior is a complicated and understudied issue that requires further examination.

Because intervention strategies have used only younger subjects, an examination of the effects on older rats has not been reported. The purpose of the current study was to examine the response of middle-aged rats to a time-based intervention that had previously been shown to improve timing and self-control in younger (3-month old) rats (Smith, Marshall, and Kirkpatrick 2015). It was hypothesized that the same overall effects of decreased SS choice and improved timing would be evident in the middle-aged sample and that the rats most prone to impulsive choice in the pre-test would benefit most from the intervention, consistent with previous findings with this intervention.

1. Material and methods

1.1. Animals

Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) were used for this experiment. The rats had been used in two previous experiments examining impulsive choices in standard discounting tasks (see Peterson, Hill, and Kirkpatrick 2015). The rats were maintained at approximately 85% of their free feeding weights, through the delivery of 45-mg pellets (BioServ) in the experimental chambers coupled with supplementary feedings of lab chow in their home cages. The rats had free access to water at all times. The colony room was maintained on a 12:12 hr reversed light:dark cycle with lights off at 7 a.m. Rats were approximately 14 months old at the commencement of experimentation.

2.2. Apparatus

The timing and choice procedures were conducted in a set of 24 identical operant chambers (Med Associates, Vermont, USA). Each chamber measured 25 × 30 × 30 cm and was housed inside of a ventilated, noise attenuating box measuring 74 × 38 × 60 cm. The chambers were located in two separate rooms, with 12 chambers in one room and 12 in the other room. Each chamber was equipped with two nose pokes, a houselight, two nose keys with cue lights, a food cup and a water bottle. The houselight was positioned in the top-center of the back wall. Two levers (ENV-122CM) were situated on either side of the food cup at approximately one third of the total height of the chamber, with lever presses recorded by a microswitch. The nose poke keys with cue lights (ENV-119M-1) were located directly above each lever. A magazine pellet dispenser (ENV-203) delivered 45-mg food pellets (BioServ; Flemington, NJ) into the food cup. The water bottle was mounted outside the chamber; water was available through a metal tube that protruded through a hole in the lower-center of the back wall. Med-PC IV controlled experimental events and recorded the time of events with a 2-ms resolution on two PC computers, each connected to 12 operant chambers.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Impulsive choice task (pre-test)

Prior to the intervention procedure, rats completed an impulsive choice task to establish a pre-intervention choice baseline using a steady-state choice procedure that the rats had previously experienced (Peterson, Hill, and Kirkpatrick 2015). Free choice trials began when both levers were inserted; a response on one of the levers resulted in the onset of the cue light above the chosen lever and the withdrawal of the alternative lever. After the target delay had elapsed, the next response resulted in the offset of the cue light and the delivery of the reinforcer. Forced choice trials began with the insertion of one lever. A response on that lever resulted in the onset of its associated cue light. The forced choice trial then proceeded in the same manner as the free choice trials. In all cases, the SS choice resulted in a one-pellet reinforcer and the LL choice resulted in a two-pellet reinforcer. The SS delay was always 5 s and the LL delay increased over sessions and each delay was delivered for 5 consecutive sessions: 5, 15, 30, and 60 s. Each session consisted of 20, 4-trial blocks, for a total of 80 trials. Each block contained two forced choice trials (1 SS and 1 LL) followed by two free choice trials (1 SS and 1 LL). There was a 60-s fixed ITI in all cases and the sessions lasted approximately 2 hr. There were 20 testing sessions total.

2.3.2. Timing intervention

The VI timing intervention from Smith et al. (2015) was utilized in this study. This intervention was chosen because it successfully increased both timing precision (within the choice task) and self-control in young rats. The VI schedule exposed rats to a uniformly-distributed set of delays ranging across the delays in the choice task. Rats have been shown to accurately track the distribution of intervals in uniform VI schedules and show orderly timing gradients (Church, Lacourse, and Crystal 1998). Tracking and timing a distribution of interval durations may potentially promote better timing accuracy and precision due to the more demanding nature of the VI schedule. In addition, the VI schedule has an advantage over simpler fixed interval exposure due to the ramping Hazard function (Evans, Hastings, and Peacock 2000). The Hazard function is the conditional probability of receiving food given that food hasn’t been delivered already. Smith et al. (2015) proposed that a ramping Hazard function may be superior in increasing self-control because the longer the animal waits the more likely it is to receive reinforcement. Thus, a gradually ramping delay of reinforcement gradient is an inherent property of uniformly-distributed VI schedules that may make them ideal candidates for interventions.

After initial impulsive choice testing, rats were matched for baseline impulsive choice behavior and then assigned to one of two conditions, intervention or control. The intervention group was trained on a variable interval (VI) 10-s schedule and a VI 30-s schedule, with the VI 10 on the SS lever and the VI 30 on the LL lever. Delays on the VI schedule were uniformly distributed and averaged 10 s (range = 0–20 s) and 30 s (range = 0–60 s). Rats were given 1 pellet on the VI 10 and 2 pellets on the VI 30 schedule. On the VI schedules, the session began with the insertion of one of the levers. The first response resulted in the onset of the VI duration. The rat was free to respond during the VI without consequence. Once the target interval elapsed, the next response resulted in food delivery. Rats received the VI schedules in blocks of 20 sessions, with half of the rats receiving VI 10 s training first and half VI 30 s first. Each session lasted until 210 total reinforcers were received (210 SS trials or 105 LL trials) or 2 hr had elapsed.

Control rats spent an equal amount of time in the operant boxes but received no procedures (no food deliveries, lever inserts, or any stimuli). Control rats received 9 g of rat chow in the magazine cup to consume while in the chamber; this amount was equal to the maximum amount that could be earned by the experimental rats during the intervention sessions. Thus, the control group received transportation, handling, exposure to the chambers, and a similar amount of food to the intervention group. The purpose of the control was to control for exposure to the experimental conditions but without inducing any exposure to time-based schedules of food delivery as any schedule of food delivery that involves a temporal component could potentially induce an intervention effect.

2.3.3. Impulsive choice task (post-test)

After completing the VI intervention, rats were reassessed with the choice procedure from Phase 1.

2.3.4. Bisection task

A temporal bisection task was used to assess the rats’ timing abilities. A trial began when the house light turned on and lasted for either a short duration (4 s) or a long duration (12 s). Both levers were then inserted and the rat was required to press the lever that corresponded to the experienced duration. The lever assignments for the short and long delays were counterbalanced across rats. Correct responses were rewarded with a single food pellet followed by a 15 s ITI. If the rat chose the incorrect lever, a correction trial began and lasted until the correct response was chosen. The ITI for the correction trials was 5 s. Sessions lasted until 80 correct choices (40 short and 40 long) were made (up to a maximum of 2 hr); there was no maximum number of correction trials. Training continued until rats reached a minimum criterion of at least 80% correct on two consecutive sessions.

Once training was completed, the rats received a series of test sessions with non-reinforced durations intermixed with normal training trials: 4, 5.26, 6.04, 6.93, 7.94, 9.12 and 12 s. Test trials were the same as training trials except that they were non-reinforced and did not incorporate any correction trials. There were two tests at each of the durations administered in each training block that were intermixed among the 80 training trials. There were 10 test sessions total. The tests produced a psychophysical function relating the sample duration to the proportion of long responses.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Mixed-effects regression models

All raw data were processed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Generalized linear mixed-effects models (Wright and London 2009) employed binomial logistic regression with a logit link function. Generalized linear mixed-effects models are comparable to repeated-measures regression analyses, but allow for parameter estimation as a function of manipulation condition (e.g., LL delay) and the individual subject (Marshall and Kirkpatrick 2016; Young et al. 2013). These models permit inclusion of both fixed and random effects. Model fitting occurred in two stages: analyses first determined the model with the best fitting random-effects structure, and then determined the model with the best fixed-effects structure that incorporated the aforementioned best fitting random-effects structure. All random effects were included as fixed effects (Young et al. 2013). The best model was the one that minimized the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The model with the minimum AIC reflects the best fit including a penalty for the expected improvement in fit due to added parameters (Burnham and Anderson 2002). Continuous predictors were mean-centered to reduce multicollinearity, and categorical predictors were effects-coded (i.e., codes summed to 0).

The dependent measures in these analyses were individual binary choices (impulsive choice: SS vs. LL; temporal bisection: Short vs. Long). The bisection task only included choices from non-reinforced test trials. All sessions for each subject during the pre- and post-tests were included in the analyses for choice and all test sessions were included from the bisection task. These data included a total of 51,798 observations from the impulsive choice task and 6,718 observations from the temporal bisection task. The fixed-and random-effects models for each of the task analyses are described in the corresponding results sections below.

Error bars are not reported in the figures given that there is currently no established methodology for computing error bars associated with mixed effects models. This is due to the inclusion of both fixed and random effects in the model, wherein the usual computations of error variance are not applicable.

2.4.2. Correlational analyses

Additional summary measures were computed for purposes of correlational analyses. For the impulsive choice task, the mean percentage of LL choices was computed for each rat across the four LL delays for the pre- and post-test impulsive choice assessments. For the bisection task, a linear function was fit to the percent long response data for the middle five durations that made up the psychophysical functions. This method has been commonly employed in the literature to characterize psychophysical functions for time (e.g., Droit-Volet, Clément, and Fayol 2008; Wearden 1995; Galtress and Kirkpatrick 2010). The fitted linear function was used to determine a Point of Subjective Equality (PSE), Difference Limen (DL), and Weber Fraction (WF). The PSE was the duration associated with 50% long choices and gives an index of the point where the rat was indifferent between the two anchor durations. The DL was equal to the duration associated with 75% long response minus the duration associated with 25% long response divided by two, providing an index of timing precision, or the slope of the psychophysical function. Steeper slopes (more precision timing) are associated with larger DL values. The WF was equal to the PSE divided by the DL, providing a measure of relative temporal precision (similar to a coefficient of variation measure). One rat from the control group was removed from the correlational analysis due to having a bisection function that highly skewed to the right. As a result, we could not computer a DL or WF measure because the function did not cross 25% within the range of durations delivered. The correlations were corrected for multiple comparisons and were conducted within SPSS version 20. Comparisons of correlation slopes between groups were also conducted using linear regression within SPSS with all variables entered simultaneously.

3. Results

3.1. Impulsive choice

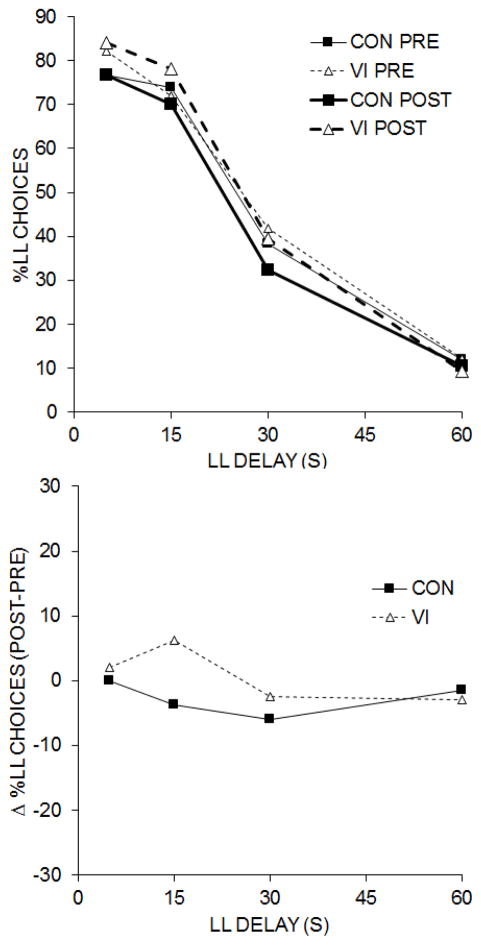

The best-fitting fixed-effects model included Group × Pre/Post × LL Delay and all lower level effects. The random effects included intercept and LL Delay. The fixed effects in the analysis revealed a main effect of Pre/Post, t(51798) = −4.359, p < .001, b = −0.052, 95% CI [−0.075, −0.029], and a main effect of LL Delay, t(51798) = −20.318, p < .001, b = −0.086, 95% CI [−0.094, −0.077]. There also was a Group × Pre/Post interaction, t(51798) = −4.574, p < .001, b = −0.054, 95% CI [−0.078, −0.031], a Pre/Post × LL Delay interaction, t(51798) = −6.353, p < .001, b = −0.004, 95% CI [−0.006, −0.003], and a Group × Pre/Post × LL Delay interaction, t(51798) = 3.443, p = .001, b = 0.002, 95% CI [0.001, 0.004]. The three-way interaction is displayed in the top panel of Figure 1, which shows the percentage of LL choices as a function of LL Delay for the two groups during the pre-test and post-test impulsive choice tasks. The two groups did not differ in their LL choices during the pre-test (gray lines), but the VI intervention produced elevated LL choices in the post-test (black lines) at the shortest delays compared to the control group pre- and post-test and VI group pre-test performance, whereas the control group showed no change at the shortest and longest LL delay and a decrease in LL choices at the middle delays compared to the pre-test. This is seen more clearly in the bottom panel of Figure 1, which displays the change in choice behavior (post – pre) as a function of LL delay. Overall, the three-way interaction was due elevated LL choices in the shorter delays in the VI group which created a steeper slope during the post-test compared to the control group and also in comparison to the pre-test choice behavior in the VI group.

Figure 1.

Top: The percentage of LL choices as a function of LL Delay for the control (CON) and intervention (VI) groups during the pre- and post-test impulsive choice tasks. Bottom: The change in the percentage of LL choices between the pre- and post-test (post-pre) for the CON and VI groups.

To assess stability of impulsive choice between pre-test and post-test, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed on the overall percentage of LL choices in each group. Both the control and VI groups showed high correlations between their pre- and post-test impulsive choice scores, r = .90, p < .001, and r = .83, p < .001, respectively. The correlations for the two groups are shown in Figure 2 in comparison to the unity line (dotted line) which is the predicted outcome if the intervention produced no effect. As shown in the figure, the control group showed a test-retest function that paralleled the unity line indicating little or no effect of the control condition on the pre-post correlation. On the other hand, the VI intervention resulted in a flatter slope in comparison to the control group and the unity line, indicating that the intervention changed the test-retest function. The slope difference was confirmed by a linear regression, which disclosed a significant group effect on the slopes, t(22) = 2.350, p = .029.

Figure 2.

Pre-test versus post-test percentage of LL choices for the control (CON) and intervention (VI) groups compared to the unity line (dotted line).

To further explore the test-retest performance, the overall LL choices (the mean of the pre- and post-test) were regressed against the change in choice behavior from pre- to post-test, which was computed by subtracting the post-test percentage of LL choices for each rat from the pre-test percentage of LL choices. Correlating the change in choice with the overall mean assesses the effect of the intervention while controlling for baseline rates and regression to the mean (Oldham 1962; Snider, Quisenberry, and Bickel 2016). The correlations are shown in Figure 3. The control group displayed a relatively constant relationship, r = .27, p = .394, indicating that the overall performance did not relate to the change in behavior as a function of exposure to the control condition. On the other hand, the VI group showed a significant negative correlation, r = −.61, p = .036, indicating that the rats that were most impulsive overall showed greater increases in LL choices following the intervention, whereas the rats that were highly LL preferring overall tended to slightly decrease their LL choices following the intervention. We also entered the scores into a regression to test the differences in the slopes (correlations) and this revealed a significant group effect, t(20) = 2.430, p = .025.

Figure 3.

The mean percentage of LL choices versus the change in percentage of LL choices between pre-test and post-test in the control (CON) and intervention (VI) groups.

3.2. Bisection task

Figure 4 displays the percentage of long responses as a function of signal duration for the two groups. The best-fitting mixed-effects model included fixed effects of intercept and sample duration with random effects of intercept and sample duration. There was a significant effect of sample duration, t(6718) = 14.539, p < .001, b = 0.448, 95% CI [0.388, 0.509]. Adding group to the model increased the AIC, and in that model, group was not significant either as a main effect or as an interaction with sample duration. Thus, there were no discernible effects of group, as is also visually confirmed in the figure.

Figure 4.

The psychophysical function relating the percentage of long responses and the signal duration for the control (CON) and intervention (VI) groups. The dotted lines denote the sample durations associated with 25% and 75% long responses for the difference limen (DL) computation and 50% long responses for the point of subjective equality (PSE) computation. Inset: The mean (standard deviation) of the PSE, DL and Weber fraction (WF) measures for the CON and VI groups.

3.3. Inter-task correlations

The pre- and post-test LL choices from the impulsive choice task were correlated with the PSE, DL, and WF measures from the bisection task (see 2.4.2 Correlational analyses). Separate correlations were conducted for each group given that the intervention altered individual differences in choice performance. There were no significant inter-task correlations in the control group with either pre- or post-test intervention choice, largest |rs| ≤ .43, ps ≥ .188, with the largest correlation being between post-intervention choice and bisection PSE. In the VI group, there also were no significant correlations between pre-intervention choice and bisection measures, rs < .48, ps > .116, but there were some significant correlations between post-test choice and bisection performance in the VI group.

Figure 5 displays the correlations between the post-test LL choices and all three bisection measures for the control and VI groups. There was no significant correlation between LL choices and the bisection PSE, r = .41, p = .180, but there was a significant correlation between LL choices and the bisection DL, r = .62, p = .033 and the bisection WF, r = .63, p = .030. In general, rats with higher percentages of LL choices in the post-test showed steeper bisection functions indicative of better temporal discrimination. For the post-test scores, we conducted a final assessment using a linear regression model to determine whether there were any group differences in the relationships between the bisection and choice variables. For the PSE, there was a near-significant interaction, t(22) = −2.000, p = .060, but there were no significant interactions for the DL, t(22) = −0.770, p = .450, or the WF, t(22) = −0.670, p = .511.

Figure 5.

Post-test percentage of LL choices versus the point of subjective equality (PSE), difference limen (DL), and Weber fraction (WF) from the bisection task for the control (CON) and intervention (VI) groups.

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of a time-based intervention on middle-aged, experienced rats. The variable interval intervention used in this experiment had previously only been utilized with young, experimentally-naive rats. It is especially compelling that the middle-aged subjects used had experience with several previous choice tasks, providing them with ample opportunities to learn to make advantageous choices, yet the treatment still resulted in a significant decrease in SS choices at the shorter LL durations. The impulsive choice task was designed so that choosing the LL resulted in more rewards earned at all LL delays because of the long ITI. Thus, the intervention promoted overall reward earning. The findings support the use of this intervention in older rats as well as young rats.

Correlations for percent LL choice in the control group were highly consistent between pre-test and post-test. This indicates a general trait stability of impulsive choice behavior in the absence of any intervention. However, in the VI treatment group, the rats that were most impulsive at pretest were significantly more likely to make LL choices after the intervention, whereas the VI rats that made high levels of LL choices pre-intervention actually decreased overall LL choices. This indicates that the intervention interacted with the expression of trait impulsivity. Although the intervention increased LL choices overall, it also decreased biases in behavior at both ends of the spectrum so that the strong SS and LL preferring rats showed some moderation in their choices. This may be an advantageous effect of the intervention because strong biases in either direction are not necessarily ideal for flexible decision making. It would be interesting to test the effect of the intervention on the flexibility of choice behavior in future work to determine whether this is indeed the case.

While the intervention did not produce an overall effect on bisection performance at the group level, it did alter individual differences correlations across tasks. There were no significant inter-task correlations found for the control rats pre- or post-intervention and the intervention group also did not show any correlation between pre-intervention choice and bisection performance. However, there was a significant correlation between post-intervention LL choices and the slope of the bisection function (measured by the DL and WF) in the intervention group. The correlation indicates that the rats that were more receptive to the intervention also showed better post-intervention temporal discrimination performance, suggesting that the intervention improved their timing processes.

The individual differences correlations between timing and choice in the intervention group are consistent with previous research reporting similar correlation patterns between timing within the choice task (measured on special peak trials) and impulsive choice (Smith, Marshall, and Kirkpatrick 2015). Moreover, the present results extend on the previous studies by demonstrating improved timing post-intervention in a separate task (i.e., outside of the impulsive choice task), indicating a potentially broader impact of the intervention on timing processes. Several studies have indicated that timing deficits are linked to impulsive choice behavior (Marshall, Smith, and Kirkpatrick 2014; McClure, Podos, and Richardson 2014; Wittmann and Paulus 2008; Baumann and Odum 2012) and that improving temporal discrimination ability leads to less impulsive choice (Smith, Marshall, and Kirkpatrick 2015). This research supports these previous findings and adds evidence that middle-aged, experienced rats show similar patterns of decreased impulsive choice behavior concomitant with improved temporal discrimination. It is possible that having to wait according to the variable interval schedule provided a potent experience for the rats that lead to an increase in willingness to wait. Indeed, Smith, Marshall, and Kirkpatrick (2015) suggested that VI exposure increases delay tolerance due to the ramping Hazard function inherent in uniform variable interval distributions (Evans, Hastings, and Peacock 2000). Further research should examine how exposure to different types of interval distributions may affect timing processes and impulsive choice behavior.

One question that remains is why the intervention did not produce an overall improvement in bisection performance at the group level. It is possible that this may be a product of working with an aging sample. Previous research in animal models as well as human participants has shown that timing and reaction speeds change with age. Research has posited that deterioration of some brain areas associated with timing (e.g. cerebral cortex and hippocampus; Cabeza, Grady, et al. 1997; Cabeza, McIntosh, et al. 1997; Iidaka, Anderson, Kapur, et al. 1999; Iidaka, Anderson, Cabeza, et al. 1999) and attention (Vanneste, Perbal, and Pouthas 1999; Vanneste and Pouthas 1999; Zakay and Block 1997) may contribute to timing changes with age. It is possible that the improved timing effects found in younger subjects did not manifest in the older sample due to some fundamental difference in timing mechanisms in some individuals within the sample, which may explain why the timing-choice relationship was apparent at the individual differences level but not at the group level. It is possible that some individual rats were demonstrating stronger aging effects than other individuals and this may explain why the timing-choice relationship was more evident at the individual differences level because the group was not demonstrating homogeneous aging effects.

Another issue is that one would have expected to observe a significant correlation between LL choices and timing precision in the bisection task in the control group based on previous findings in the literature (Marshall, Smith, and Kirkpatrick 2014; McClure, Podos, and Richardson 2014), but this relationship was not observed. Marshall et al. (2014) reported a moderately strong correlation between temporal precision in a bisection task and LL choices in an impulsive choice task, indicating that the bisection task predicted choice behavior in the absence of any intervention. It is possible that age-related changes in timing and/or choice behavior may have uncoupled this relationship in the aged control rats, but that the intervention may have re-established the relationship. Without a young comparison group, it is difficult to know whether this is the case or not. In terms of intervention effects on timing and choice, Smith et al. (2015) reported that a VI intervention significantly improved timing precision on special peak trials embedded within the impulsive choice task. However, they did not measure timing outside of the choice task as was conducted here, so it is difficult to know why different patterns of results were obtained in the present study. It is possible that the bisection task measures some different aspect of timing in comparison to measurements taken within the choice task, which presumably more directly reflect timing of the actual choice options (see Galtress, Garcia, and Kirkpatrick 2012). Clearly, further research is needed to understand the complexities of the relationship between timing and choice behavior when measured both within and outside of the choice task. In addition, more research with older subjects should assess the effects of time-based interventions on timing and choice in this age-group in comparison with younger rats.

Given the critical importance of trait impulsivity to such a wide range of problem behaviors, developing methods for mitigating impulsive choice is an important venture. These problems apply not only to the young. Individuals still gamble, abuse drugs, and make poor choices as they age, thus driving the importance of developing interventions that can apply to a range of age groups. To that end, the findings of this experiment are important because they support the use of the variable interval intervention for decreasing impulsive choice in middle-aged rats. Future research should examine intervention effects comparatively across age groups to see whether there are aging effects on the efficacy or mechanism of action of the intervention, thus building on the present results.

Highlights.

Impulsive choice behavior is a primary risk factor for other maladaptive behaviors in any age group

A variable interval intervention was utilized in experienced middle-aged rats to increase self-control

The intervention also increased temporal discrimination in a bisection task

Variable interval training is a robust intervention for middle-aged rats

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Catherine Hill and Andrew Marshall for assistance gathering data for this project. This research was supported by NIH grant MH085739 awarded to Kimberly Kirkpatrick and Kansas State University. Jennifer Peterson has since relocated to the University of Alaska-Fairbanks.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alessi SM, Petry NM. Pathological gambling severity is associated with impulsivity in a delay discounting procedure. Behavioural Processes. 2003;64:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Odum AL. Impulsivity, risk taking, and timing. Behavioural Processes. 2012;90:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder LM, Dixon MR, Ghezzi PM. A procedure to teach self-control to children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2000;33:233–237. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsakou P, Psychogiou L, Thompson M, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Delay aversion in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: an empirical investigation of the broader phenotype. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomhower SR, Rasmussen EB, Doherty TS. Impulsive-choice patterns for food in genetically lean and obese Zucker rats. Behavioral Brain Research. 2013;241:214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multi-Model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. 2. Springer; Secaucus, NJ, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Grady CL, Nyberg L, McIntosh AR, Tulving E, Kapur S, Jennings JM, Houle S, Craik FI. Age-related differences in neural activity during memory encoding and retrieval: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci. 1997;17:391–400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00391.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, McIntosh AR, Tulving E, Nyberg L, Grady CL. Age-related differences in effective neural connectivity during encoding and recall. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3479–83. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199711100-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RM, Lacourse DM, Crystal JD. Temporal search as a function of the variability of interfood intervals. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1998;24:291–315. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.24.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellu-Hagedorn F, Trunet S, Simon H. Impulsivity in youth predicts early age-related cognitive deficits in rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:525–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Hayes LJ, Binder LM, Manthey S, Sigman C, Zdanowski DM. Using a self-control training procedure to increase appropriate behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:203–210. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Holcomb S. Teaching self-control to small groups of dually diagnosed adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:611–614. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Rehfeldt RA, Randich L. Enhancing tolerance to delayed reinforcers: The role of intervening activities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:263–266. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet S, Clément A, Fayol M. Time, number and length: Similarities and differences in discrimination in adults and children. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61:1827–1846. doi: 10.1080/17470210701743643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Adornetto M. Generalized self-control of delay and effort. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1020–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Evans M, Hastings N, Peacock B. Statistical Distributions. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Galtress T, Garcia A, Kirkpatrick K. Individual differences in impulsive choice and timing in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2012;98:65–87. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2012.98-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtress T, Kirkpatrick K. Reward magnitude effects on temporal discrimination. Learning and Motivation. 2010;41:108–124. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Robinson BM, McMahon RP, Gold JM. Delay discounting in schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12:213–221. doi: 10.1080/13546800601005900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iidaka T, Anderson N, Kapur S, Cabeza R, Okamoto C, Craik FIM. Age-related differences in brain activation during encoding and retrieval under divided attention: A positron emission tomography (PET) study. Brain and Cognition. 1999;39:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Iidaka T, Anderson ND, Cabeza R, Fergus Craik IM, Sadato N, Yonekura Y. Age-related differences in brain activation as revealed by positron emission tomography (pet). Divided attention study of episodic memory in young and old adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1999:73–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jimura K, Myerson J, Hilgard J, Keighley J, Braver TS, Green L. Domain independence and stability in young and older adults’ discounting of delayed rewards. Behavioural Processes. 2011;87:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick K, Marshall AT, Smith AP. Mechanisms of individual differences in impulsive and risky choice in rats. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews. 2015;10:45–72. doi: 10.3819/ccbr.2015.100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune H, Ferrara A, Soffie M, Bronchart M, Wearden JH. Peak procedure performance in young adult and aged rats: acquisition and adaptation to a changing temporal criterion. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1998;51:193–217. doi: 10.1080/713932681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AT, Kirkpatrick K. Mechanisms of impulsive choice: III. The role of reward processes. Behavioural Processes. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AT, Smith AP, Kirkpatrick K. Mechanisms of impulsive choice: I. Individual differences in interval timing and reward processing. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2014;102:86–101. doi: 10.1002/jeab.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE, Logue AW. Choice in a “self-control” paradigm: Effects of a fading procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1978;30:11–17. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1978.30-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure J, Podos J, Richardson HN. Isolating the delay component of impulsive choice in adolescent rats. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2014;8:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1999;146:455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef NA, Bicard DF, Endo S. Assessment of impulsivity and the development of self-control in students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:397–408. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef NA, Marckel J, Ferreri SJ, Bicard DF, Endo S, Aman MG, Miller KM, Jung S, Nist L, Armstrong N. Behavioral assessment of impulsivity: A comparison of children with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:23–37. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.146-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. J Exp Anal Behav. 2011;96:427–39. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL. Delay discounting: trait variable? Behav Processes. 2011;87:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham PD. A note on the analysis of repeated measurements of the same subjects. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1962;15:969–977. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(62)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JR, Hill CC, Kirkpatrick K. Measurement of impulsive choice in rats: Same- and alternate-form test-retest reliability and temporal tracking. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103:166–179. doi: 10.1002/jeab.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JR, Hill CC, Marshall AT, Stuebing SL, Kirkpatrick K. I can’t wait: methods for measuring and moderating individual differences in impulsive choice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Industrial Organization. 2015;13:89–99. doi: 10.1515/jafio-2015-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Casarella T. Excessive discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers with gambling problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer JB, Sulzer-Azaroff B. Self-control in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects of added stimulation and time. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:671–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NW, LaSarge CL, Montgomery KS, Williams MT, Mendez IA, Setlow B, Bizon JL. Good things come to those who wait: Attenuated discounting of delayed rewards in aged Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:853–862. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AP, Marshall AT, Kirkpatrick K. Mechanisms of impulsive choice: II. Time-based interventions to improve self-control. Behavioural Processes. 2015;112:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, Quisenberry AJ, Bickel WK. Order in the absence of an effect: Identifying rate-dependent relationships. Behavioural Processes. 2016;127:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Johnson PS, Renda CR, Smits RR, Liston KJ, Shahan TA, Madden GJ. Early and prolonged exposure to reward delay: Effects on impulsive choice and alcohol self-administration in male rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21:172–180. doi: 10.1037/a0031245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Renda CR, Hinnenkamp JE, Madden GJ. Impulsive choice, alcohol consumption, and pre-exposure to delayed rewards: II. Potential mechanisms. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103:33–49. doi: 10.1002/jeab.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, Perbal S, Pouthas V. Estimation of duration in young and aged subjects: The role of attentional and memory processes. Annee Psychologique. 1999;99:385–414. [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, Pouthas V. Timing in aging: The role of attention. Experimental Aging Research. 1999;25:49–67. doi: 10.1080/036107399244138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearden JH. Categorical scaling of stimulus duration by humans. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1995;21:318–330. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.21.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller RE, Cook EW, Avsar KB, Cox JE. Obese women show greater delay discounting than healthy-weight women. Appetite. 2008;51:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Paulus MP. Decision making, impulsivity and time perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DB, London K. Multilevel modelling: Beyond the basic applications. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009;62:439–56. doi: 10.1348/000711008X327632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ME, Webb TL, Rung JM, Jacobs EA. Sensitivity to changing contingencies in an impulsivity task. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:335–45. doi: 10.1002/jeab.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D, Block RA. Temporal Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1997;6:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zauberman G, Kim BK, Malkoc SA, Bettman JR. Discounting Time and Time Discounting: Subjective Time Perception and Intertemporal Preferences. Journal of Marketing Research. 2009;46:543–556. [Google Scholar]