Abstract

Objective

China is the largest producer of tobacco worldwide. We assessed secular trends in prevalence of smoking, average cigarettes per day, mean age of initiation, and mortality attributable to smoking among the Chinese population between 1991 and 2011.

Design

Data came from the China Health and Nutrition Survey, conducted eight times between 1991 and 2011. A total of 83,447 participants aged 15 years or older were included in this study. Trends in smoking were stratified by sex, age, and region (urban vs. rural).

Results

In 2011, 311 millions individuals were current smokers in China, with 295 million men and 16 million women, respectively. Between 1991 and 2011, the prevalence of current smoking decreased from 60.6% to 51.6% in men, and from 4.0% to 2.9% in women. However, during this period, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day per smoker increased from 15.0 to 16.5 in males, and from 8.5 to 12.4 in females. Further, age of smoking initiation decreased from 21.9 to 21.4 years in men and from 31.4 to 28.4 years in women. In 2011, 16.5% of all deaths in men and 1.7% in women were due to smoking. Between 1991 and 2011, the total number of deaths caused by smoking increased from 800,000 to 900,000.

Conclusions

During the past 20 years, a slight decrease in smoking prevalence was observed in the Chinese population. However, cigarette smoking remains a major cause of death in China, especially in men.

Keywords: Smoking, Epidemiology, Trends, China

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the leading risk factor for many non-communicable diseases and premature mortality worldwide (Chen et al., 2015; WHO, 2015). Tobacco use was responsible for 4.8 million deaths in 2000 and 6.0 million in 2011 worldwide (Asma et al., 2014; Ezzati and Lopez, 2003). By 2030, tobacco use is expected to cause 8.3 million deaths, accounting for 10% of the all-cause mortality globally (Mathers and Loncar, 2006). China is the largest tobacco producer worldwide. The number of cigarettes produced in China increased from 0.5 trillion in 1980 to 2.6 trillion in 2013, corresponding to 43% of the current world’s tobacco production. 99% of cigarettes produced in China are consumed domestically and only 1% exported (Yang et al., 2008). It has been estimated that >300 million adults were smokers in China, accounting for a third of the world’s total number of smokers (No authors listed, 2011). As a result, China bears tremendous economic and disease burdens attributable to smoking. In 2008, smoking was estimated to have cost China about $5 billion for treatment of smoking-related diseases (direct costs) and $29 billion in total economic lost (direct and indirect costs) (No authors listed, 2014b; Yang et al., 2011). Tobacco has been estimated to account for 9.5% of disability-adjusted life-years and 16.4% of deaths among Chinese adults (Koplan et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013).

In consideration of the great number of smokers and the large health hazard attributable to smoking, the Chinese government has adopted a wide range of interventions to curb tobacco use, including tax increases, bans on advertising, and smoke-free laws. Furthermore, the Chinese government ratified the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2005. Despite these efforts, a number of serious challenges remain. The Global Adults Tobacco Survey (GATS) showed that 28.1% of Chinese adults (52.9% of men and 2.4% of women) were current smokers in 2010 (Li et al., 2011). In addition, among the 16 countries that had completed the survey, China ranked second for smoking among men, between Russia (60.2%) and Ukraine (50.0%) (Giovino et al., 2012).

In China, patterns of tobacco use have evolved along social and economic development and progress of implementation of tobacco control policies. However, only few studies have documented trends in smoking and the impact on mortality in the Chinese population (Chen et al., 2015; Giovino et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2009; Lam et al., 1997; Qian et al., 2010). Monitoring trends in smoking and its impact is critical for policy makers in order to guide appropriate tobacco control interventions. Hence, based on data of successive national Chinese surveys (the China Health and Nutrition Surveys, CHNS), we assessed secular trends in smoking, average number of cigarettes smoked daily, mean age of smoking initiation, and mortality attributable to smoking in the Chinese population between 1991 and 2011.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and subjects

The CHNS is designed as a national, large scale survey to examine the health and nutritional status of the Chinese population over time. It is an international collaborative project between the Carolina Population Center of the University of North Carolina and the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention since 1989. Surveys are carried out using a multistage random cluster sampling strategy to obtain population based data in nine Chinese provinces (Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guizhou and Guangxi), which vary in geography, economic status, public resources, and health indicators. Detailed information of CHNS has been published elsewhere (Popkin et al., 2010).

Between 1991 and 2011, a total of 83,447 participants aged 15 years or older in eight surveys (9394 in 1991, 8784 in 1993, 11,149 in 1997, 10,116 in 2000, 10,313 in 2004, 10,099 in 2006, 10,278 in 2009, and 13,314 in 2011) were included in data analyses. Characteristics of the survey participants are shown in the Supplemental Table 1. The participation rate was >98% in each survey.

Written informed consents were obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board from both the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

2.2. Definitions

Between 1991 and 2011, smoking habits were assessed by 4 questions that were kept identical in each survey. The first question was “Have you ever smoked cigarettes (including hand-rolled, device-rolled or pipe)?” Responses included “never smoked” and “yes”. The second question was “Do you still smoke cigarettes now?” Participants who answered “yes” were defined as “current smoker”. The third question was “How many cigarettes do you smoke per day?”. The fourth question was “How old were you when you started to smoke?”.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as percentage (SE), while continuous variables were presented as mean (SE). The estimates of current smoking or ever smoking, number of cigarettes used per day and the initiation age by sex, age, and region are described in this study. The sex-and age- specific China census distribution of the population in 2010 was used to standardize estimates in all surveys. Trends in prevalence of current smoking and ever smoking between 1991 and 2011 were examined using multiple logistic regression adjusted for sex, age and region; trends in number of cigarettes smoked per day and age of smoking initiation were assessed by similarly adjusted multiple linear regression. To calculate the population attributable risk (PAR) of smoking, we used the following formula: PAR = (P × [RR −1]) ÷ (P × [RR − 1] + 1), where P is the prevalence of smokers, and RR is the relative risk of disease or mortality (Gu et al., 2009). Estimates for RRs for all-cause mortality, cancer, respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease were extracted from a publication by Chen et al. (2015). All data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS (version 16.0). Two-side p values of <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

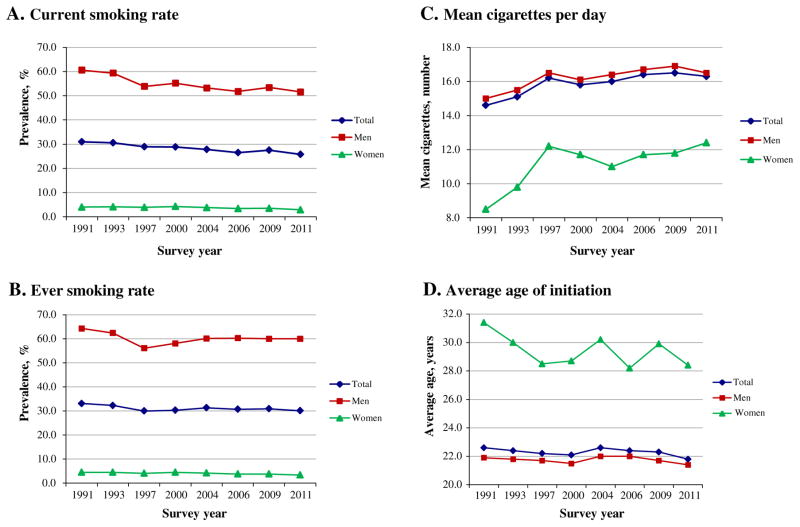

Supplemental Table 1 presents characteristics of the study populations in each survey between 1991 and 2011. There were differences across the eight surveys, with increasingly old and urban populations. Table 1 shows trends in prevalence of current smoking by sex, age, and region between 1991 and 2011. In 2011, it was estimated that 311 millions individuals were current smokers in China, with 295 million men and 16 million women, respectively. The prevalence of smoking decreased from 1991 to 2011 in both sexes, i.e., from 60.6% to 51.6% in men and from 4.0% to 2.9% in women, respectively (for both sexes, p for trends <0.001) (Fig. 1A). Decreasing prevalence was found in all age and region (urban/rural) subgroups (p for trend <0.001) except for younger women aged 15–24 years for which the decrease did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.223).

Table 1.

Trends in the prevalence of current smoking in China, 1991–2011.

| 1991

|

1993

|

1997

|

2000

|

2004

|

2006

|

2009

|

2011

|

P for trendsa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | ||

| Total | 31.0 | 0.5 | 30.6 | 0.5 | 28.9 | 0.4 | 28.8 | 0.5 | 27.8 | 0.4 | 26.5 | 0.4 | 27.5 | 0.4 | 25.8 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 18.8 | 0.8 | 19.6 | 0.9 | 15.0 | 0.7 | 16.0 | 1.0 | 12.9 | 1.0 | 14.4 | 1.2 | 17.3 | 1.3 | 15.1 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| 25–44 | 34.7 | 0.7 | 32.9 | 0.8 | 33.5 | 0.7 | 31.2 | 0.7 | 30.4 | 0.8 | 27.6 | 0.8 | 28.6 | 0.8 | 25.9 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 36.7 | 1.0 | 35.9 | 1.0 | 34.8 | 0.9 | 32.6 | 0.8 | 31.3 | 0.7 | 30.3 | 0.7 | 30.0 | 0.7 | 28.6 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 28.4 | 1.6 | 29.4 | 1.6 | 22.4 | 1.2 | 25.1 | 1.2 | 23.4 | 10.8 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 24.2 | 1.0 | 22.8 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||

| Men | 60.6 | 0.7 | 59.4 | 0.8 | 53.9 | 0.7 | 55.2 | 0.7 | 53.2 | 0.7 | 51.8 | 0.7 | 53.4 | 0.7 | 51.6 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Women | 4.0 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 30.6 | 0.8 | 30.5 | 0.9 | 28.0 | 0.8 | 27.5 | 0.8 | 26.7 | 0.7 | 26.0 | 0.7 | 26.0 | 0.7 | 24.1 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 31.2 | 0.6 | 30.7 | 0.6 | 29.3 | 0.5 | 29.5 | 0.6 | 28.3 | 0.6 | 26.8 | 0.5 | 28.2 | 0.6 | 27.0 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Men | |||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 38.0 | 1.5 | 38.1 | 1.6 | 28.1 | 1.3 | 30.2 | 1.7 | 23.0 | 1.7 | 27.2 | 20.7 | 32.0 | 2.2 | 30.6 | 2.2 | <0.001 |

| 25–44 | 71.8 | 1.0 | 68.5 | 1.1 | 64.6 | 1.0 | 63.7 | 1.1 | 61.6 | 1.2 | 57.9 | 1.2 | 58.8 | 1.3 | 55.2 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 65.8 | 1.4 | 65.2 | 1.4 | 63.6 | 1.2 | 61.3 | 1.2 | 60.0 | 1.1 | 58.0 | 1.1 | 58.0 | 10.8 | 56.8 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 49.0 | 2.7 | 51.5 | 2.6 | 39.4 | 2.2 | 42.3 | 2.1 | 40.6 | 1.9 | 37.7 | 1.8 | 43.8 | 1.7 | 41.2 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 59.5 | 1.3 | 58.7 | 1.4 | 52.5 | 1.2 | 52.7 | 1.2 | 50.4 | 1.2 | 50.2 | 1.2 | 51.0 | 1.2 | 48.3 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 61.0 | 0.9 | 59.8 | 0.9 | 54.5 | 0.8 | 56.5 | 0.9 | 54.6 | 0.9 | 52.7 | 0.9 | 54.7 | 0.9 | 54.0 | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Women | |||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | – | – | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.223 |

| 25–44 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.004 |

| 45–64 | 8.5 | 0.8 | 8.0 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 11.9 | 1.6 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 8.3 | 1.1 | 10.1 | 1.2 | 9.2 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 0.8 | 6.8 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 4.7 | 0.5 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 3.6 | 0.3 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

SE: standard error of prevalence.

Adjusted for age, sex and region when appropriate.

Fig. 1.

Trends in (A) the prevalence of current smoking, (B) prevalence of ever smoking; (C) mean cigarettes smoked per day per smoker; and (D) average age of smoking initiation in the Chinese population, 1991–2011. Data are age- and sex- standardized to the 2010 China Census population.

The prevalence of current smoking was highest for men aged 25–44 years old and 45–64 years old. In women, prevalence of smoking was much lower compared with men in each survey year; in 2011, the prevalence ratio of smokers was 1 woman for 18 men. In men, the prevalence of smoking was slightly higher in rural than urban areas in a consistent manner between 1991 and 2011. In women, while the prevalence was higher in urban than rural areas until 2004, the urban-rural difference vanished thereafter. For the prevalence of ever smoking, similar trends were found in the total population and in sex, age and region subgroups (Supplemental Table 2 and Fig. 1B). In addition, during the period of 1991 to 2011, the prevalence of former smoking increased from 3.7% to 8.4% in men, while it remained stable at 0.5% in women.

Among current smokers, the number of cigarettes smoked per day increased from 15.0 to 16.5 in men and from 8.5 to 12.4 in women (Supplemental Table 3 and Fig. 1C). Similar upward trends were found in most age and region subgroups. In men, subjects aged 45–64 years experienced the highest increase in mean number of cigarettes smoked per day among all four age groups. In women, the greatest increase occurred in subjects aged 25–44 years.

The mean age of smoking initiation declined in the whole population and in most age and region subgroups between 1991 and 2011(for most subgroups, p for trends <0.001). We restricted this analysis to subjects aged 25 years or older as the daily smoking rates were not stable for individuals aged 15–24 years. The decrease was more important in women (from 31.4 to 28.4 years old; difference of 3.0 years) compared to men (from 21.9 to 21.4 years old; difference of 0.5 years) (Supplemental Table 4 and Fig. 1D). In each survey, mean age of initiation was lower for men than women. Furthermore, mean age of initiation was lower for rural than urban female smokers while no obvious region difference was found in male smokers.

In China, the total number of deaths from any cause increased from 5.9 million in 1990 to 7.0 million in 2010 (Yang et al., 2015). In 2011, the proportion of deaths due to smoking (i.e., the population attributable risk) was 16.5% in men and 1.7% in women. When applied to the whole population, this proportion corresponds to 900,000 deaths (800,000 in men and 100,000 in women). Between 1991 and 2011, the proportion of deaths due to smoking slightly decreased because of the small reduction in smoking prevalence on both sexes (Table 2). However, the number of deaths attributable to smoking increased markedly, from 800,000 in 1991 to 900,000 in 2011 (men: 700,000 to 800,000; women: 100,000 to 100,000).

Table 2.

Trends in mortality attributable to smoking in China, 1991–2011.

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk (95% CI)b | Population attributable risk, % (95% CI)

|

Relative risk (95% CI)b | Population attributable risk, % (95% CI)

|

|||||

| 1991 | 2000 | 2011 | 1991 | 2000 | 2011 | |||

| All causes | 1.33 (1.28–1.39) | 17.5 (15.3–20.0) | 16.1 (14.0–18.5) | 16.5 (14.4–19.0) | 1.51 (1.40–1.63) | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) | 1.7 (3.5–17.8) |

| Cancer | ||||||||

| All | 1.51 (1.40–1.63) | 24.7 (20.5–28.8) | 22.9 (18.9–26.8) | 23.4 (19.4–27.4) | 1.58 (1.37–1.81) | 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | 1.9 (1.2–2.7) |

| Lung | 2.58 (2.17–3.05) | 50.4 (42.9–56.9) | 47.9 (40.5–54.4) | 48.7 (41.2–55.2) | 2.56 (2.02–3.26) | 6.6 (4.4–9.2) | 6.6 (4.4–9.2) | 5.0 (3.4–7.1) |

| Liver | 1.26 (1.06–1.50) | 14.3 (3.7–24.3) | 13.1 (3.4–22.5) | 13.5 (3.5–23.1) | 1.40 (0.93–2.12) | 1.8a | 1.8a | 1.3a |

| Stomach | 1.25 (1.05–1.49) | 13.8 (3.1–24.0) | 12.7 (2.8–22.2) | 13.0 (2.9–22.7) | 1.43 (0.92–2.23) | 1.9a | 1.9a | 1.4a |

| Oesophagus | 1.58 (1.30–1.93) | 27.2 (16.2–37.4) | 25.2 (14.8–35.1) | 25.8 (15.3–35.8) | 1.05 (0.55–2.01) | 0.2a | 0.2a | 0.2a |

| Five minor sites | 1.53 (1.15–2.04) | 25.4 (8.8–40.1) | 23.5 (8.0–37.7) | 24.1 (8.3–38.4) | 0.98 (0.55–1.75) | a | a | a |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||

| All | 1.24 (1.16–1.33) | 13.4 (9.3–17.5) | 12.2 (8.5–16.1) | 12.6 (8.8–16.5) | 1.44 (1.27–1.63) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 1.5 (0.9–2.1) |

| IHD | 1.38 (1.23–1.54) | 19.6 (12.9–25.8) | 18.1 (11.8–23.9) | 18.6 (12.1–24.5) | 1.74 (1.42–2.12) | 3.2 (1.9–4.8) | 3.2 (1.9–4.8) | 2.5 (1.4–3.7) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1.41 (1.15–1.73) | 20.9 (8.8–31.9) | 19.2 (8.0–29.8) | 19.7 (8.3–30.5) | 1.15 (0.74–1.78) | 0.7a | 0.7a | 0.5a |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) | 1.9a | 1.7a | 1.8a | 1.09 (0.86–1.39) | 0.4a | 0.4a | 0.3a |

| All respiratory | 1.64 (1.42–1.90) | 29.2 (21.3–36.7) | 27.1 (19.6–34.3) | 27.7 (20.1–35.1) | 1.78 (1.46–2.17) | 3.4 (2.0–5.0) | 3.4 (2.0–5.0) | 2.6 (1.5–3.8) |

| All other medical diseases | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 11.4 (3.7–18.8) | 10.4 (3.4–17.3) | 10.7 (3.5–17.8) | 1.41 (1.13–1.76) | 1.8 (0.6–3.3) | 1.8 (0.6–3.3) | 1.4 (0.4–2.5) |

CI, confidence interval.

The PAR or 95% CI cannot be calculated.

Extracted from the publication by Chen et al. (2015).

4. Discussion

In 2011, smoking remained common in the Chinese population (about 311 millions current smokers), especially in men. Between 1991 and 2011, the prevalence of smoking declined slightly in both sexes, and the number of cigarettes smoked daily increased and the age of smoking initiation decreased in all sex, age, and region subgroups. Importantly, the number of deaths attributable to smoking increased from 800,000 in 1991 to 900,000 in 2011 despite the slight decrease in the prevalence of smokers. Cigarette smoking remains a major public health threat in China.

The prevalence of smoking was high in China, especially among men. In the early 1970s, a regional survey including 9351 middle-aged smokers in Shanghai found that 61% of men and 7% of women were smokers (Lam et al., 1997); in 1976, the corresponding figures from another regional survey in Xi’an were 56% and 12% (Chen et al., 1997). Based on national data from the National Health Service Survey (NHSS), it was reported that the prevalence of current smoking decreased from 59.6% in 1993 to 48.9% in 2003 in men, and from 5.1% in 1993 to 3.2% in 2003 in women (Qian et al., 2010). A recent nationally representative survey f(China Non-communicable Disease Surveillance) showed that 54.1% of men and 2.6% of women were current smokers in 2011 (Bi et al., 2015) and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2008–2010 showed that 52.9% of men and 2.4% of women were current smokers in China (Giovino et al., 2012). While these observations are consistent with our findings, the comparability between these surveys is limited by differences in study design, sample sources, geographic coverage, and definition of smoking. Major strengths of the CHNS data used in the current study are the same study design, same geographic regions, and same definition of smoking across all surveys between 1991 and 2011, which allows direct comparison of findings over time.

The prevalence of smoking in China is particularly high compared to other countries around the world, at least for men (Giovino et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2014). In 2008–2010, data from 16 countries indicated that China had the second highest prevalence (52.9%) of smoking among men behind Russia (60.2%) (Giovino et al., 2012). In 2012, a large review including 187 countries suggested that 12 countries including China had a smoking prevalence of >40% in males and accounted for nearly 40% of all smokers globally (Ng et al., 2014). These findings underline the large scale of the smoking epidemic in China, and the urgent need to strengthen tobacco control interventions.

The prevalence of smoking was much higher in men than women. In addition, men started to smoke cigarettes earlier than women. Although the Chinese society has been influenced by the western culture during the past decade, it remains quite conservative and rooted into the traditional Confucian idea. The society is quite tolerant to male smoking but not to female smoking (Kim, 2005). These socio-cultural characteristics might be a major factor in the largely higher smoking prevalence and earlier onset of smoking in men than women.

In 2011, we estimate that cigarette smoking caused about 16.5% of all male deaths and 1.7% of all female deaths in China based on the prevalence of smoking found in our study and RRs of diseases due to smoking estimated by Chen et al. (2015) A previous study by Gu et al. reported that cigarette smoking accounted for 12.9% of deaths in men and 3.1% of deaths in women in China (Gu et al., 2009). Most recently, Chen et al. showed that 18% of deaths in men and 3% of deaths in women were attributable to tobacco use in China (Chen et al., 2015). The risk of mortality attributable to smoking was much smaller in women than in men mainly due to the much lower prevalence of smoking in men than women although the RRs of diseases due to smoking were similar for both sexes.

In our study, the proportion of deaths due to smoking slightly de-creased over time because of the slight reduction in smoking prevalence on both sexes between 1991 and 2011. However, the absolute number of deaths attributable to smoking increased, consistent with the increasing size of the Chinese population during the past 20 years. It is likely that the absolute number of deaths in China attributable to tobacco will continue to rise because of the continued population growth, unless the prevalence of smoking decreases. This serious situation underlines the need to strengthen tobacco control interventions in China. However, the reported RR for all-cause mortality in the Chinese population was markedly lower (e.g., 1.21–1.33 for men) (Chen et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2009) than that reported in many western countries (e.g., 2.8 for men) (Thun et al., 2013). It seems that cigarettes smoking may pose less serious effect on health in Chinese population than in western countries. However, future studies are necessary to further determine the underlying biological mechanism on why smoking play different roles in human health across different populations.

The slight decrease in the prevalence of current smoking suggested that China made some progress in tobacco control. However, major gaps still exist when compared to the WHO FCTC requirements. Several barriers impede tobacco control in China (Yang et al., 2015). First, there is a large conflict between the huge scale of the tobacco industry in China, largely controlled by the government, and tobacco control policies. Government is reluctant to scale down an industry that it controls and this industry is a large source of tax revenues. Second, effective interventions are not available to support smoking cessation. Although > 800 cessation clinics have been set up in China since 1996, few smokers are using these clinics. Third, warnings only cover 30% of the bottom of packages of cigarettes, compared to the size of at least 50% as recommended by the WHO FCTC (Kaul and Wolf, 2014; No authors listed, 2014a). Fourth, tax accounted for only 40–46% of the tobacco product retail price in 2011, which is much lower than the proportion required by the WHO FCTC (70%). (Yang et al., 2015) Thus, cigarettes in China are quite inexpensive, with an average price of ¥5.0 (around US $0.74) for one pack of locally manufactured cigarettes (Jena et al., 2012). Fifth, there was no national legislation in China to ban tobacco in public and work places until 2014, as well as no limitation on tobacco advertising. Finally, smoking is still socially accepted, and cigarettes are still regarded as a courtesy in most social events in China, such as weddings, funerals, and official activities. Expensive cigarettes are a usual gift for relatives, friends, guests or visitors (Rich and Xiao, 2012).

Our study has several strengths. It includes a large number of participants (n = 83,447) with a large response rate in each survey (98% or more). Furthermore, the same standardized protocol was used to collect smoking information in each of the eight national surveys. In addition, strict quality control measures were applied in each survey, including trained examiners and calibrated instruments. Nevertheless, several limitations should also be noted. First, the CHNS only included nine provinces out of the 31 Chinese provinces, and our findings may not necessarily be generalized to the whole China. Second, information on cigarette smoking was based on self-report, and some recall or reporting bias is expected. As a result, the prevalence of smoking may be underestimated. Third, we only reported the trends in prevalence of cigarette smoking rather than the prevalence of any other forms of tobacco use. However, it has been previously shown that cigarettes account for >95% of all tobacco products used in China (Giovino et al., 2012). Fourth, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study design, the inferences should be drawn with caution. Fifth, our study provided secular trends in smoking estimates over time according to a limited number of characteristics (age, sex, and region). Future studies are needed to investigate other factors that might have influenced these changes.

In conclusion, this study shows that although the prevalence of smoking slightly decreased since 1991, it remains very high in 2011, especially in men. Furthermore, the daily number of cigarette increased over time and the initiation age of smoking decreased during the past ~20 years. Importantly, the absolute number of deaths due to smoking increased between 1991 and 2011 because of the increasing size of the population. To control the epidemic of cigarette smoking, the Chinese government should strengthen a tobacco control measures and stop supporting the local tobacco industry. In addition, government should increase tobacco taxation, further implement bans on smoking in public place, ban advertisement promotion and sponsoring of tobacco product measures and further develop tobacco cessation programs. Fortunately, at the end of 2014, the China State Council released a long-anticipated guideline on national tobacco control, followed by tobacco control legislation. The potential for public health benefit of stricter tobacco control measures is huge: it was estimated that >12.8 million smoking-related deaths by 2050 in China could be prevented if the provisions recommended by the WHO FCTC were implemented (Levy et al., 2014).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants R01-HD30880, DK056350, R24-HD050924, and R01-HD38700). The sponsors have no role in the study design, survey process, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

We thank the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety of China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and Carolina Population Center of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for sharing their valuable data. We thank Pascal Bovet (Division of Chronic Diseases, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (IUMSP), Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland) for help improve the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CHNS

China Health and Nutrition Surveys

- FCTC

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- GATS

Global Adults Tobacco Survey

- RR

Relative risk

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.027.

Footnotes

Contributors

BX was involved in the study conception and design. SL, LM, AC, and CM provided statistical expertise. SL, LM and BX drafted the article; BX and AC revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version. BX is the guarantor.

Declaration of interests

None.

References

- Asma S, Song Y, Cohen J, Eriksen M, Pechacek T, Cohen N, Iskander J Centers for Disease, C., Prevention. CDC grand rounds: global tobacco control. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:277–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Jiang Y, He J, Xu Y, Wang L, Xu M, Zhang M, Li Y, Wang T, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in Chinese adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1013–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZM, Xu Z, Collins R, Li WX, Peto R. Early health effects of the emerging tobacco epidemic in China. A 16-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997;278:1500–1504. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.18.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Shin YS, Beaglehole R. Tobacco control in China: small steps towards a giant leap. Lancet. 2012;379:779–780. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Peto R, Zhou M, Iona A, Smith M, Yang L, Guo Y, Chen Y, Bian Z, et al. Contrasting male and female trends in tobacco-attributed mortality in China: evidence from successive nationwide prospective cohort studies. Lancet. 2015;386:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00340-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362:847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, Gupta PC, Jarvis MJ, Bhala N, Peto R, Zatonski W, Hsia J, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012;380:668–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, Chen J, Samet JM, Huang JF, Zhu M, Chen JC, Chen CS, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China. J Med]–>N Engl J Med. 2009;360:150–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena PK, Kishore J, Bandyopadhyay C. Prevalence and patterns of tobacco use in Asia. Lancet. 2012;380:1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62108-4. (author reply 1906–1907) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul A, Wolf M. Standardised packaging and tobacco-industry-funded research. Lancet. 2014;384:233–234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH. Korean adolescents’ smoking behavior and its correlation with psychological variables. Addict Behav. 2005;30:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplan JP, An WK, Lam RM. Hong Kong: a model of successful tobacco control in China. Lancet. 2010;375:1330–1331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TH, He Y, Li LS, Li LS, He SF, Liang BQ. Mortality attributable to cigarette smoking in China. JAMA. 1997;278:1505–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Rodriguez-Buno RL, Hu TW, Moran AE. The potential effects of tobacco control in China: projections from the China SimSmoke simulation model. BMJ. 2014;348:g1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Hsia J, Yang G. Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. J Med]–>N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2469–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1102459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Wollum A, Sanman E, Wulf S, et al. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:183–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China’s unhealthy relations with big tobacco. Lancet. 2011;377:180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60028-7. No authors listed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigarette packaging in China–not going far enough. Lancet. 2014a;383:1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60667-X. No authors listed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A step change for tobacco control in China? Lancet. 2014b;384:2000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62319-9. No authors listed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, Zhang B. Cohort profile: the China Health and Nutrition Survey—monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China, 1989–2011. J Epidemiol]–>Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1435–1440. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Cai M, Gao J, Tang S, Xu L, Critchley JA. Trends in smoking and quitting in China from 1993 to 2003: National Health Service Survey data. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:769–776. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich ZC, Xiao S. Tobacco as a social currency: cigarette gifting and sharing in China. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:258–263. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, Hartge P, Gapstur SM. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. J Med]–>N Engl J Med. 2013;368:351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. 2015 http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf.

- Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W, Wan X, Zhai Y, Chen LC, Koplan JP. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Sung HY, Mao Z, Hu TW, Rao K. Economic costs attributable to smoking in China: update and an 8-year comparison, 2000–2008. Tob Control. 2011;20:266–272. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.042028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, Wan X, Yu S, Jiang Y, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381:1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Wang Y, Wu Y, Yang J, Wan X. The road to effective tobacco control in China. Lancet. 2015;385:1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.