Abstract

The present study was conducted to gain insights into the occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- (ESBL-) producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) from drinking well water in the rural area of Laiwu, China, and to explore the role of the nearby pit latrine as a contamination source. ESBL-producing E. coli from wells were compared with isolates from pit latrines in the vicinity. The results showed that ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, with the same antibiotic resistance profiles, ESBL genes, phylogenetic group, plasmid replicon types, and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-polymerase chain reaction (ERIC-PCR) fingerprints, were isolated from well water and the nearby pit latrine in the same courtyard. Therefore, ESBL-producing E. coli in the pit latrine may be a likely contributor to the presence of ESBL-producing E. coli in rural well water.

1. Introduction

The use of cephalosporins in clinical practices of humans and animals has contributed to the occurrence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- (ESBL-) producing bacteria across the world [1, 2]. These bacteria are resistant to most beta-lactam antibiotics, such as first-, second-, third-, and fourth-generation cephalosporins, which would increase medical costs and limit treatment options [3, 4].

Many species of Gram-negative bacteria can produce ESBLs, but ESBLs are mainly detected in Enterobacteriaceae, particularly in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella spp. [5]. It is worrisome that not only are ESBL-producing E. coli associated with community-acquired infections, especially urinary tract infection [6, 7], but also they have been isolated from food-producing animals and healthy human populations [8, 9].

ESBL-producing E. coli in the intestinal tracts of humans and animals are easily excreted into the environment, particularly into surface water bodies. Numerous studies have shown that ESBL-producing E. coli can be detected in water bodies [10–13].

Human exposure to ESBL-producing E. coli in water bodies may easily occur, for example, when contaminated surface water is used for recreation, for irrigation of crops, or as a drinking water source [14, 15]. Similarly, animal exposure to ESBL-producing E. coli in water bodies may also easily occur, for instance, when they drink contaminated surface water [1]. To limit the spread of ESBL-producing E. coli via water bodies, it is pivotal to understand the possible contamination sources.

To date, numerous researches about contamination sources of ESBL-producing E. coli have been focusing on hospital environments, animal farms, rivers and lakes, and wastewater treatment plants [10, 12, 16–19]. But data about the prevalence and possible contamination sources of ESBL-producing E. coli in rural water well in undeveloped regions is very limited.

In undeveloped areas of China, plenty of domestic wells are used to supply drinking water. Impurities from the surface easily enter wells, so the rural wells are relatively easy to be contaminated by bacteria. More importantly, most bacteria, especially ESBL-producing E. coli, could contaminate well water coming from fecal material from humans and animals, for instance, from on-site sanitation systems, such as pit latrines and septic tanks [20]. But little information about ESBL-producing E. coli contamination in well waters is available in China. This study was therefore conducted to gain insights into the prevalence and characterization of ESBL-producing E. coli from drinking well water in the rural area of Laiwu, China, and to explore the role of the nearby pit latrine as a contamination source.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Well Selection and Homeowner Enrollment

The sampling site was located in the rural area of Laiwu city of China, in which the majority of households have both a shallow drinking well (approximately 12–18 m in depth) and a pit latrine in their courtyards, and the distance between them is about 8–10 m. To minimize the influence of surrounding surface water and animal fecal material on the groundwater, water wells located near pit latrines and not within 100 m of rivers/lakes or animal farms were favored for selection in this study. In addition, the distance between two sampled wells is no less than 100 m.

Owners of water wells were sent a letter describing the study and were telephoned two days later to request their participation and confirm that their water well was near a pit latrine.

2.2. Sample Collection

Between July and August 2014, a 500 mL well water sample was collected using a sterile bottle from each well (100 wells). During the same period, wastewater samples from 100 pit latrines located near the wells were obtained using the same method. All samples were immediately transported to our lab in an icebox and processed in 6 h.

2.3. Isolation and Identification of ESBL-Producing E. coli

Each water sample was filtered using a membrane filter (0.45 μm). The filter was then spread on MacConkey agar plate containing cefotaxime (4 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C overnight. A suspected E. coli colony was identified using API 20E (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France).

The suspected ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were confirmed by phenotypic confirmatory tests using cefotaxime (30 μg), cefotaxime + clavulanic acid (30 μg/10 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), and ceftazidime + clavulanic acid (30 μg/10 μg) [21].

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were tested for susceptibility to a panel of 16 antibiotics: ampicillin (10 μg), piperacillin (100 μg), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20/10 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), and chloramphenicol (30 μg). Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed according to the CLSI guidelines [21]. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain. Isolates from the same sampling site were considered as duplicate strains if they showed the same antibiotic resistance profiles [22].

2.5. Detection of Beta-Lactamase Gene

Based on the previously published reference [23], ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were subjected to multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine the presence/absence of genes encoding CTX-M, SHV, and TEM. PCR products were sequenced and compared with beta-lactamase gene sequences in the GenBank database and in the Lahey website (http://www.lahey.org/studies).

2.6. Phylogenetic Groups

ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were assigned to eight groups, A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F, and clade I, according to the published work by Clermont and his colleagues [24].

2.7. Plasmid Replicon Typing

According to the previously published references [25, 26], ESBL-producing E. coli were subjected to PCR-based plasmid replicon typing. Briefly, PCR amplification was carried out with 18 pairs of primers to recognize FIA, FIB, FIC, HI1, HI2, I1-Iγ, L/M, N, P, W, T, A/C, K, B/O, X, Y, F, and FIIA in 5 multiplex and 3 simplex reactions.

2.8. ERIC-PCR

ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were subjected to enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus- (ERIC-) PCR [27–29]. ERIC-PCR fingerprints were analyzed using the NTSYSpc software (version 2.02K, Applied Biostatistics, Inc., NY, USA). The dendrogram was constructed based on the average relatedness of the matrix using the algorithm of the unweighted pair-group method (UPGMA) in the SAHN program of the NTSYSpc software.

3. Results

3.1. ESBL-Producing E. coli Isolates

One hundred households with private wells (W1–W100) and pit latrines (P1–P100) in their courtyard were selected to be sampled. A total of 200 samples from 100 wells and 100 pit latrines were obtained in this study. ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from the same sampling site were considered as duplicate strains if they showed the same antibiotic resistance profiles [22], and 63 nonduplicate ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were obtained in this study, including 23 isolates from 5 wells (W2, W16, W21, W24, and W35; 5/100, 5.0%) and 40 strains from 8 pit latrines (P2, P16, P21, P24, P35, P40, P46, and P56; 8/100, 8.0%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sixty-three nonduplicate ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well water and pit latrine wastewater.

| Wells | Isolate ID | Number | Pit latrines | Isolate ID | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W2 | W2-1 | 4 | P2 | P2-1 | 7 |

| W2-2 | P2-2 | ||||

| W2-3 | P2-3 | ||||

| W2-4 | P2-4 | ||||

| P2-5 | |||||

| P2-6 | |||||

| P2-7 | |||||

|

| |||||

| W16 | W16-1 | 5 | P16 | P16-1 | 7 |

| W16-2 | P16-2 | ||||

| W16-3 | P16-3 | ||||

| W16-4 | P16-4 | ||||

| W16-5 | P16-5 | ||||

| P16-6 | |||||

| P16-7 | |||||

|

| |||||

| W21 | W21-1 | 4 | P21 | P21-1 | 6 |

| W21-2 | P21-2 | ||||

| W21-3 | P21-3 | ||||

| W21-4 | P21-4 | ||||

| P21-5 | |||||

| P21-6 | |||||

|

| |||||

| W24 | W24-1 | 5 | P24 | P24-1 | 8 |

| W24-2 | P24-2 | ||||

| W24-3 | P24-3 | ||||

| W24-4 | P24-4 | ||||

| W24-5 | P24-5 | ||||

| P24-6 | |||||

| P24-7 | |||||

| P24-8 | |||||

|

| |||||

| W35 | W35-1 | 5 | P35 | P35-1 | 6 |

| W35-2 | P35-2 | ||||

| W35-3 | P35-3 | ||||

| W35-4 | P35-4 | ||||

| W35-5 | P35-5 | ||||

| P35-6 | |||||

| P40 | P40-1 | 3 | |||

| P40-2 | |||||

| P40-3 | |||||

| P46 | P46-1 | 1 | |||

| P56 | P56-1 | 2 | |||

| P56-2 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Total | 23 | 40 | |||

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of ESBL-Producing E. coli

Similar resistance characteristics of ESBL-producing E. coli between two origins were found in this study. All ESBL-producing E. coli from well water and pit latrine wastewater were resistant to ampicillin (100%) and cephalothin (100%), and most of the ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well waters were resistant to cefuroxime (95.6%), piperacillin (78.3%), tetracycline (78.3%), nalidixic acid (56.5%), and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (56.5%); resistance to ciprofloxacin (43.8%) and ceftriaxone (39.1%) was also common; resistance to gentamicin (30.4%), chloramphenicol (30.4%), ceftazidime (26.1%), and cefepime (13.0%) was less frequently observed; none of the strains was resistant to amikacin or carbapenem antibiotics imipenem and meropenem (Table 2).

Table 2.

Resistance profiles of ESBL-producing E. coli from well water and pit latrine wastewater.

| Antibiotics | Prevalence of resistance isolates, number (column%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Well water (n = 23) | Wastewater (n = 40) | |

| Ampicillin (AMP) | 23 (100) | 40 (100) |

| Piperacillin (PRL) | 18 (78.3) | 28 (70.0) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC) | 13 (56.5) | 11 (32.5) |

| Cephalothin (CF) | 23 (100) | 40 (100) |

| Cefuroxime (CXM) | 22 (95.6) | 39 (97.5) |

| Ceftazidime (CAZ) | 6 (26.1) | 18 (45.0) |

| Ceftriaxone (CRO) | 9 (39.1) | 20 (50.0) |

| Cefepime (CPM) | 3 (13.0) | 3 (7.5) |

| Imipenem (IPM) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem (MEC) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Amikacin (AMK) | 0 (0) | 4 (10.0) |

| Gentamicin (GM) | 7 (30.4) | 25 (62.5) |

| Nalidixic acid (NA) | 13 (56.5) | 27 (67.5) |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 10 (43.8) | 29 (72.5) |

| Tetracycline (TE) | 18 (78.3) | 23 (57.5) |

| Chloramphenicol (C) | 7 (30.4) | 15 (37.5) |

The majority of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from pit latrine wastewater were resistant to cefuroxime (97.5%), ciprofloxacin (72.5%), piperacillin (70.0%), nalidixic acid (67.5%), gentamicin (62.5%), and tetracycline (57.5%); resistance to ceftriaxone (50.0%) and ceftazidime (45.0%) was also common; but resistance to chloramphenicol (37.5%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (32.5%), amikacin (10%), and cefepime (7.5%) was less frequently observed; none of the strains was resistant to carbapenem antibiotics imipenem and meropenem (Table 2).

3.3. β-Lactamase Genes of ESBL-Producing E. coli

Except that bla CTX-M-3 gene was restricted to pit latrine wastewater isolates, a similar distribution of β-lactamases genes among both sources was found in this study. Twenty-two out of 23 well water isolates (95.6%) and 37 of 40 pit latrine wastewater isolates (92.5%) carried bla CTX-M genes. Fifteen out of 23 well water isolates (65.2%) and 30 of 40 pit latrine wastewater isolates (75.0%) carried bla TEM-1 genes, and most of these isolates combined with bla CTX-M genes. Among all ESBL-producing E. coli carrying bla CTX-M genes, the most prevalent ESBL gene was bla CTX-M-15. No bla SHV genes were detected in this study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of β-lactamase genes by source group among ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well water and pit latrine wastewater. Note: TEM-1 is not an ESBL.

| β-Lactamases genes | Prevalence of β-lactamases genes, number (column%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Well water (n = 23) | Wastewater (n = 40) | |

| bla CTX-M-3 | 0 | 4 (10.0%) |

| bla CTX-M-14 | 6 (26.1%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| bla CTX-M-15 | 8 (34.8%) | 19 (47.5%) |

| bla CTX-M-55 | 3 (13.0%) | 6 (15.0%) |

| bla CTX-M-64 | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| bla TEM-1-type | 15 (65.2%) | 30 (75.0%) |

| bla SHV-1-type | 0 | 0 |

3.4. Phylogenetic Groups of ESBL-Producing E. coli

The phylogenetic group distribution of ESBL-producing E. coli from well water and pit latrine wastewater was comparable. 39.1% and 26.1% of ESBL-producing E. coli from well water belonged to group A and group B1, respectively. Similarly, 32.5% and 22.5% of ESBL-producing E. coli from wastewater belonged to group A and group B1. 26.1% and 8.7% of the well water isolates belonged to groups D and B2, respectively. 27.5% and 17.5% of the wastewater isolates belonged to groups D and B2, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of phylogenetic groups among ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well water and pit latrine wastewater.

| Phylogenetic group | Prevalence of phylogenetic group, number (column%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Well water (n = 23) | Wastewater (n = 40) | |

| A | 9 (39.1) | 13 (32.5) |

| B1 | 6 (26.1) | 9 (22.5) |

| B2 | 2 (8.7) | 11 (27.5) |

| D | 6 (26.1) | 7 (17.5) |

3.5. Plasmid Replicon Typing of ESBL-Producing E. coli

Of 18 studied plasmid replicon types, 8 were not detected. All isolates carried at least one of the tested plasmid replicon types. The dominant plasmid replicons among well water isolates were FIB (60.1%) and replicon IncI1 (43.5%). Similarly, the most prevalent plasmid replicons among wastewater isolates were IncI1 (70.0%) and FIB (50.0%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of plasmid replicons of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well water and pit latrine wastewater.

| Plasmid replicon | Prevalence of replicon within source group, number (column%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Well water (n = 23) | Human fecal waste (n = 40) | |

| FIB | 14 (60.1) | 20 (50.0) |

| FIA | 5 (21.7) | 19 (47.5) |

| IncI1 | 10 (43.5) | 28 (70.0) |

| N | 3 (13.0) | 4 (10.0) |

| F | 4 (17.4) | 3 (7.5) |

| A/C | 1 (4.3) | 3 (7.5) |

| Y | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) |

| L/M | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| P | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| HI1 | 2 (8.7) | 1 (2.5) |

3.6. ERIC-PCR Analysis

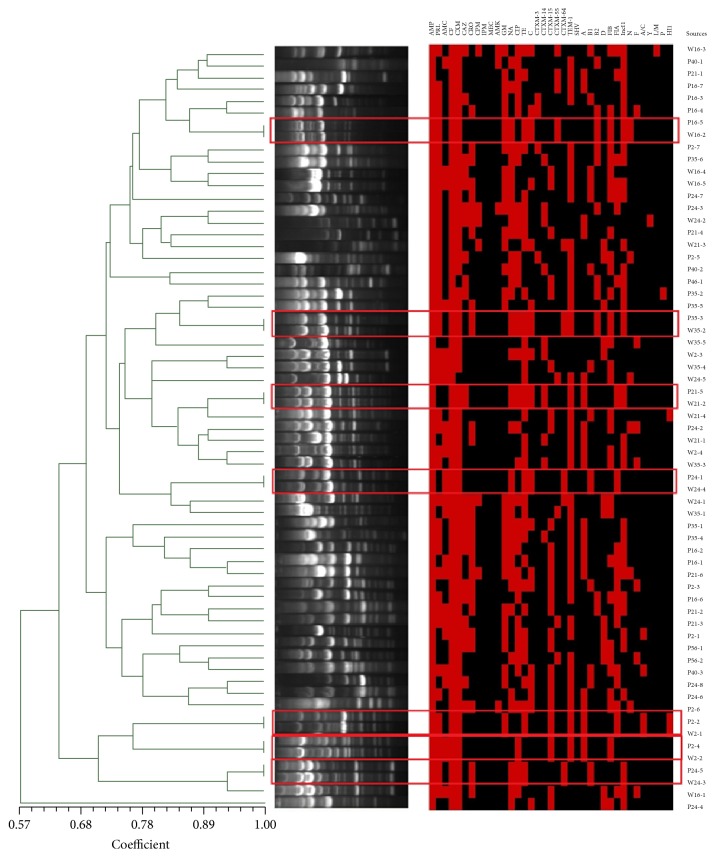

ERIC analysis showed that genetic relatedness of all ESBL-producing E. coli isolates ranged between 57.0% and 100.0%. Overall, the isolates from well water and wastewater were extensively intermixed. Of note, seven isolates from five different wells showed 100.0% genetic similarity with isolates from the pit latrine in the same courtyard (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ERIC analysis of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from both well water and pit latrine wastewater. Notes: the dendrogram was constructed based on the average relatedness of the matrix using the algorithm of the unweighted pair-group method (UPGMA) in the SAHN program of the NTSYSpc software. P: pit latrine; W: well water; the red square represents the presence of related phenotypes, genotypes, phylotyping, and plasmid replicons. AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; CF: cephalothin; CXM: cefuroxime; CAZ: ceftazidime; CRO: ceftriaxone; CPM: cefepime; IPM: imipenem; MEC: meropenem; AMK: amikacin; GM: gentamicin; NA: nalidixic acid; CIP: ciprofloxacin; TE: tetracycline; C: chloramphenicol.

4. Discussion

In this study, there were 7 matches (100.0% similarity) among ESBL-producing E. coli from two source groups in the same courtyard. These findings suggested that pit latrine wastewater might be an important source for ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from well water.

High resistance rates of ESBL-producing E. coli for β-lactamases and other antibiotic classes were observed in this study, which is consistent with previous studies about ESBL-producing E. coli from water bodies of China or other countries [30–32]. Additionally, relatively high resistance rates to fluoroquinolone (72.5%), ciprofloxacin (62.5%), and gentamicin (62.5%) from wastewater samples were observed, which is related to the fact that those antimicrobials are widely used by humans in China [33, 34]. Of note, compared with pit latrine wastewater, ESBL-producing E. coli from well water showed higher rates of resistance against tetracycline (78.3% versus 57.5%), which is frequently used in veterinary practice [33]. Therefore, the higher proportion of tetracycline resistant strains in well water isolates may be associated with the contamination of animal-borne bacteria. Fortunately, only 4.0% of wastewater isolates were resistant to amikacin, and 100.0% of the isolates were susceptible to imipenem and meropenem.

In both source groups, the predominant CTX-M-1 group gene was bla CTX-M-15, and bla CTX-M-14 was the most prevalent CTX-M-9 group gene, which is in agreement with several other reports in China [33, 35]. Additionally, bla CTX-M-15 and bla CTX-M-14 were used to represent the epidemic CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-9 groups in humans in Asia, respectively [36]. Of note, bla CTX-M-55 was relatively prevalent in isolates from both sources, which is frequently found in human and food-producing animals in China [34, 37]. bla CTX-M-64 was detected in isolates from both sources, which could have resulted from recombination of bla CTX-M-55 and bla CTX-M-14 [34, 38, 39]. In addition, bla TEM-1-type gene was found in both sources, but the lack of identification of TEM-1-type variants by direct sequencing was a limitation of the study.

Several studies have shown that ESBL-producing E. coli from patients, poultry, and environmental waters had the same ESBL genes, resistance profiles, and genomic backbone [33, 40]. Similarly, ESBL-producing E. coli exhibiting identical antibiotic resistance profiles, ESBL genes, phylogenetic group, plasmid replicon types, and ERIC fingerprints were isolated from well water and the pit latrine in the same courtyard. The result suggested that there is possible transmission of bacteria carrying resistance gene between pit latrine wastewater and well water.

There was a similar phylogroup distribution between both sources, and the prevalent groups were A and B1. Phylogroup A is common in commensal strains from chickens [41]. Also, phylogroup B1 is prevalent among extraintestinal infectious isolates from humans, and group B2 is the most prevalent phylogroup among isolates from humans [39, 42]. The existence of groups B1 and B2 isolates in well water might be an indication of virulent human isolates being spread into the water bodies.

With respect to mobile elements, such as plasmid replicons and β-lactamases genes, the high overlap between ESBL-producing E. coli from both sources suggested that the transfer of mobile elements may have occurred from fecal wastewater source isolates to well water ones [43].

5. Conclusions

Together, these findings showed that ESBL-producing E. coli isolates with the same antibiotic resistance profiles, ESBL genes, phylogenetic group, plasmid replicon types, and ERIC-PCR fingerprints were isolated from well water and the nearby pit latrine in the same courtyard. Therefore, it could be concluded that pit latrine wastewater may be an important contributor to the presence of ESBL-producing E. coli in well water, and ESBL-producing E. coli may disseminate from pit wastewater to well water through long-term permeation or water runoff, especially during heavy rains.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Special Grant of Innovation Team of Shandong Province (SDAIT-13-011-11) and the Development Plan of Science and Technology of Shandong Province (no. 2014GSF119024).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

Hongna Zhang and Yanxia Gao contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Cantón R., Novais A., Valverde A., et al. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2008;14(1):144–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castanheira M., Mendes R. E., Rhomberg P. R., Jones R. N. Rapid emergence of blaCTX-M among Enterobacteriaceae in U.S. Medical Centers: molecular evaluation from the MYSTIC Program (2007) Microbial Drug Resistance. 2008;14(3):211–216. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantón R., Akóva M., Carmeli Y., et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(5):413–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris P. N. A., Tambyah P. A., Paterson D. L. β-Lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae: time for a reappraisal in the era of few antibiotic options? The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2015;15(4):475–485. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(14)70950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falagas M. E., Karageorgopoulos D. E. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing organisms. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2009;73(4):345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson D. L., Bonomo R. A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2005;18(4):657–686. doi: 10.1128/cmr.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livermore D. M., Canton R., Gniadkowski M., et al. CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2007;59(2):165–174. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trott D. β-lactam resistance in Gram-negative pathogens isolated from animals. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2013;19(2):239–249. doi: 10.2174/138161213804070339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H., Zhou Y., Guo S., Chang W. High prevalence and risk factors of fecal carriage of CTX-M type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from healthy rural residents of Taian, China. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6, article 239 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su H.-C., Ying G.-G., Tao R., Zhang R.-Q., Zhao J.-L., Liu Y.-S. Class 1 and 2 integrons, sul resistance genes and antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from Dongjiang River, South China. Environmental Pollution. 2012;169:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaak H., De Kruijf P., Hamidjaja R. A., Van Hoek A. H. A. M., De Roda Husman A. M., Schets F. M. Prevalence and characteristics of ESBL-producing E. coli in Dutch recreational waters influenced by wastewater treatment plants. Veterinary Microbiology. 2014;171(3-4):448–459. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaak H., Lynch G., Italiaander R., Hamidjaja R. A., Schets F. M., de Roda Husman A. M. Multidrug-resistant and extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Dutch surface water and wastewater. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127752.e0127752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S., Song W., Zhou Y., Tang Y., Gao Y., Miao Z. Spread of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from a swine farm to the receiving river. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2015;22(17):13033–13037. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4575-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., Zhou Y., Guo S., Chang W. Prevalence and characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from rural well water in Taian, China, 2014. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2015;22(15):11488–11492. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H., Zhou Y., Guo S., Chang W. Multidrug resistance found in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from rural water reservoirs in Guantao, China. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6, article 267 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radimersky T., Frolkova P., Janoszowska D., et al. Antibiotic resistance in faecal bacteria (Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp.) in feral pigeons. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2010;109(5):1687–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gündoğdu A., Jennison A. V., Smith H. V., Stratton H., Katouli M. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in hospital wastewaters and sewage treatment plants in Queensland, Australia. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2013;59(11):737–745. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohnishi M., Okatani A. T., Esaki H., et al. Herd prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae producing CTX-M-type and CMY-2 β-lactamases among Japanese dairy farms. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2013;115(1):282–289. doi: 10.1111/jam.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S., Zhao M., Liu J., Zhou Y., Miao Z. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance profiles of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from healthy broilers in Shandong Province, China. China Journal of Food Protection. 2016;79:1169–1173. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Infectious Diseases, Rogan W. J., Brady M. T. Drinking water from private wells and risks to children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1599–1605. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 23rd Informational Supplement (M100-S23) Wayne, Pa, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gandolfi-Decristophoris P., Petrini O., Ruggeri-Bernardi N., Schelling E. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in healthy companion animals living in nursing homes and in the community. American Journal of Infection Control. 2013;41(9):831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dallenne C., Da Costa A., Decré D., Favier C., Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010;65(3):490–495. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clermont O., Christenson J. K., Denamur E., Gordon D. M. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environmental Microbiology Reports. 2013;5(1):58–65. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carattoli A., Bertini A., Villa L., Falbo V., Hopkins K. L., Threlfall E. J. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2005;63(3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zurfluh K., Jakobi G., Stephan R., Hächler H., Nüesch-Inderbinen M. Replicon typing of plasmids carrying 1 blaCTX-M-1 in Enterobacteriaceae of animal, environmental and human origin. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2014;5, article 555 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hulton C. S. J., Higgins C. F., Sharp P. M. ERIC sequences: a novel family of repetitive elements in the genomes of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and other enterobacteria. Molecular Microbiology. 1991;5(4):825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versalovic J., Koeuth T., Lupski J. R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991;19(24):6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramazanzadeh R., Zamani S., Zamani S. Genetic diversity in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli by enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-PCR technique in Sanandaj hospitals. Iranian Journal of Microbiology. 2013;5:126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu S.-Y., Zhang Y.-L., Geng S.-N., et al. High diversity of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in an urban river sediment habitat. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(17):5972–5976. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00711-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korzeniewska E., Harnisz M. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Enterobacteriaceae in municipal sewage and their emission to the environment. Journal of Environmental Management. 2013;128:904–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C., Li J., Chen P., Ding R., Zhang P., Li X. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistances in soils from wastewater irrigation areas in Beijing and Tianjin, China. Environmental Pollution. 2014;193:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu Y.-Y., Cai J.-C., Zhou H.-W., et al. Molecular typing of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli isolates from environmental water, swine feces, specimens from healthy humans, and human patients. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013;79(19):5988–5996. doi: 10.1128/aem.01740-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J., Zheng B., Zhao L., et al. Nationwide high prevalence of CTX-M and an increase of CTX-M-55 in Escherichia coli isolated from patients with community-onset infections in Chinese county hospitals. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(1, article 659) doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao L. L., Lv L. C., Zeng Z. L., et al. Increasing prevalence of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli in food animals and the diversity of CTX-M genotypes during 2003–2012. Veterinary Microbiology. 2014;172(3-4):534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ewers C., Bethe A., Semmler T., Guenther S., Wieler L. H. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: a global perspective. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(7):646–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B. T., Yang Q. E., Li L., et al. Dissemination and characterization of plasmids carrying oqxAB-blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia coli isolates from food-producing animals. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073947.e73947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seiffert S. N., Hilty M., Perreten V., Endimiani A. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant gram-negative organisms in livestock: an emerging problem for human health? Drug Resistance Updates. 2013;16(1-2):22–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kluytmans J. A. J. W., Overdevest I. T. M. A., Willemsen I., et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from retail chicken meat and humans: comparison of strains, plasmids, resistance genes, and virulence factors. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;56(4):478–487. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leverstein-van H. M., Dierikx C. M., Cohen S. J., et al. Dutch patients, retail chicken meat and poultry share the same ESBL genes, plasmids and strains. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2011;17(6):873–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clermont O., Bonacorsi S., Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(10):4555–4558. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakobsen L., Kurbasic A., Skjøt-Rasmussen L. Escherichia coli isolates from broiler chicken meat, broiler chickens, pork, and pigs share phylogroups and antimicrobial resistance with community-dwelling humans and patients with urinary tract infection. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2010;142:264–272. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huijbers P. M. C., Graat E. A. M., Haenen A. P. J., et al. Extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in broilers and people living and/or working on broiler farms: prevalence, risk factors and molecular characteristics. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2014;69(10):2669–2675. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]