Abstract

This study investigated the effects of a past concussion on electrophysiological indices of attention in college athletes. Forty-four varsity football athletes (22 with at least one past concussion) participated in three neuropsychological tests and a two-tone auditory oddball task while undergoing high-density event-related potential (ERP) recording. Athletes previously diagnosed with a concussion experienced their most recent injury approximately 4 years before testing. Previously concussed and control athletes performed equivalently on three neuropsychological tests. Behavioral accuracy and reaction times on the oddball task were also equivalent across groups. However, athletes with a concussion history exhibited significantly larger N2 and P3b amplitudes and longer P3b latencies. Source localization using standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography indicated that athletes with a history of concussion generated larger electrical current density in the left inferior parietal gyrus compared to control athletes. These findings support the hypothesis that individuals with a past concussion recruit compensatory neural resources in order to meet executive functioning demands. High-density ERP measures combined with source localization provide an important method to detect long-term neural consequences of concussion in the absence of impaired neuropsychological performance.

Keywords: : adult brain injury, electrophysiology, cognitive function, neuropsychology, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Between 1.6 and 3.8 million sports-related concussions occur in the United States annually.1 Recently, the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine emphasized the need to identify individuals at risk for long-term impairments post-concussion.2 This issue is particularly relevant for collegiate football athletes, a group whose annual injury rates continue to increase.3 Though concussions cost the United States an estimated $60 billion annually,4 research has thus far failed to identify an objective marker to detect the occurrence of a concussion nor an objective means to determine when it is safe for a player to return to play or return to their academic studies.

A sequelae of symptoms and cognitive impairments characterize the acute stages post-concussion,5 but typically resolve within 1–2 weeks. For example, McCrea and colleagues found that approximately 91% of collegiate football athletes reported resolved symptoms within 7 days post-injury.6 Likewise, athletes' cognitive status in this study returned to pre-injury levels between 5 and 7 days post-injury. Other research suggested that concussed college athletes perform equivalent to healthy athletes on traditional neuropsychological tests as few as 3 days post-injury.7 However, computer-based assessments (e.g., Immediate Post Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing; ImPACT) administered during preseason baseline testing, fail to differentiate athletes with and without a history of concussion, nor groups of athletes with one, two, or three past concussions.8,9 Two independent and competing conclusions may be drawn from these findings: 1) There are no long-term cognitive impairments associated with concussion, or 2) these tests are not sensitive to the long-term consequences of concussion.

Findings from retrospective research challenge the accuracy of the first conclusion. Guskiewicz and colleagues reported that former athletes reporting three or more concussions were 5 times more likely to be diagnosed with a mild cognitive impairment (MCI).10 Former athletes were also 3 times more likely to be diagnosed with depression11 and report significant memory problems.10 A history of concussion is also associated with post-mortem taupathy linked to Alzheimer's disease12 and chronic traumatic encephalopathy.13 In light of the relationship between past concussion and later development of neurodegenerative diseases, it is important to identify sensitive markers of the long-term consequences experienced post-concussion so that more-effective steps can be taken to maximize recovery.

Functional brain recording techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG), are sensitive to long-term neurological impairments that follow concussion.14 One aspect of the EEG, the event-related potential (ERP), is a waveform that is time-locked to the onset of a specific stimulus. ERPs comprise an advantageous tool for examining neurological changes post-concussion because they are reliable, objective, and highly sensitive.15 In this report, we focus our attention on two components of the ERP, the P3b and the N2.

P3b event-related potential component

The P3b (or P300) component is commonly elicited during “oddball” attention paradigms in which a participant responds only to a “target” stimulus that is infrequently presented among more-frequent occurring stimuli.16 The P3b comprises the third large positive component of the ERP waveform. This peak occurs between 300 and 800 ms after presentation of a target stimulus and reaches its maximal amplitude over central-parietal electrode areas.16–18 The amplitude of the P3b is thought to represent context updating,15 the allocation of attentional resources during a cognitive task,19 and the expectation for an event,16 such as in the oddball task.20 The more infrequent the occurrence of an expected stimulus, the larger the expected amplitude.21 The latency of the P3b, or the temporal occurrence (in ms) after stimulus onset of the most positive peak, is thought to reflect stimulus evaluation speed whereby more-frequent stimuli exhibit an earlier latency than less-frequent stimuli.21 Researchers generally reported decreased P3b amplitudes during oddball tasks in concussed, compared to nonconcussed, athletes.22–24 Investigators interpreted that smaller P3b amplitudes in concussed athletes indicates that decreased neural resources are available to perform cognitive tasks.

N2 event-related potential component

The second component investigated in this article, the N2, occurs temporally immediately before the P3b. This component has a frontocentral maximum and with a negative peak amplitude maximum that typically occurs between 100 and 300 ms after stimulus onset.25 The N2 is thought to represent visual attention, alerting, and response inhibition.26,27 The amplitude of the N2 is larger during tasks in which a response to a stimulus is withheld compared to a stimulus in which a response is required.27 Unlike the P3b, the relationship between N2 morphology and concussion appears more tenuous, although there are markedly fewer studies investigating this component. Using attention-type tasks, researchers reported that athletes with a concussion history and noninjured controls generated equivalent-sized N2 amplitudes to target stimuli.22,23 However, other research reported larger N2 amplitudes in athletes and children with a history of concussion and closed-head–injured patients.28–30 The current study seeks to compliment previous N2 investigations and clarify whether the N2 component is sensitive to concussion history.

Brain areas impacted by concussion

An ongoing debate in the concussion literature concerns the direction of change in brain activity associated with concussion. ERP investigations suggest that concussions are associated with a reduction in neural activity (i.e., smaller ERP amplitudes) and reduced processing efficiency during cognitive tasks.22,23 Some studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) report similar decreases in brain activity (blood-oxygen-level dependent [BOLD] signal) in concussed athletes compared to controls during working memory and attention tasks.31,32 Specifically, these brain regions of reduced activity included the dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex (dlPFC), which is thought to underlie working memory processing. However, the concussed athletes in both of these studies also exhibited increased brain activation in a diffuse network of areas outside those regions known to support working memory and included additional frontal, temporal, and parietal networks.31 Taken together, these studies suggest that athletes with a past concussion show reduced activation in typical brain areas supporting working memory, but increased brain responses in regions outside the working memory network. Other research reported increased brain activity in both expected and diffuse networks of regions in concussed individuals.

For example, studies indicated that a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) group generated increased activation within the right parietal, right dlPFC, and bilateral frontal and parietal regions compared to controls during high working memory loads.33–35 These findings are supported by longitudinal investigations tracking long-term effects of concussion on brain activity underlying working memory.36 Compared to pre-season fMRI scans, athletes that experienced a concussion generated the most pronounced BOLD signal increases within regions supporting working memory (e.g., dlPFC) and widely distributed areas of the brain, including the superior and inferior parietal regions and bilateral middle frontal gyri.36 Fewer studies examined changes in neural activation underlying attention in individuals with concussion. Using a selective attention task, one study reported that individuals experiencing an mTBI failed to show reduced activation of the default mode network during conditions of high attentional load.37 Taken together, these findings from working memory and attention studies lie in contrast to those reporting decreased BOLD responses in athletes with a past concussion.31,32 The current study aims to contribute to this body of research in order to shed light on the different neural response patterns in athletes with a history of concussion.

One interpretation of the past literature is that increased brain activity in the absence of behavioral differences suggests that brain injury may result in the recruitment and inclusion of additional neural resources to meet current task demands. Several theories in the neurocognitive and TBI literature support these hyperactive brain findings in concussed individuals. For example, the compensation-related utilization of neural circuits hypothesis suggests that increased age is associated with larger activation of neural networks needed to perform cognitive tasks.38 In the TBI literature, Ricker and colleagues hypothesized that individuals who experienced a TBI reallocate diffuse networks of neural resources to maintain cognitive performance.39 Molfese also theorized that concussion disrupts neural networks supporting cognition, such that additional neural mechanisms are recruited to meet task demands.40 Similar to aging individuals, concussed athletes' increased brain activity during cognitive tasks may represent an adaptive mechanism designed to compensate for cognitive changes.

This apparent paradox in both the ERP and fMRI literature highlights the need for research using high-density ERP and source localization techniques to elucidate how a history of concussion influences the recruitment of neural networks engaged during cognitive activities. Scientists suggest that the neuoropathological effects of head trauma, such as in concussion, may be focal and/or diffuse.41 Specifically, that a brain injury results in diffuse axonal injury—the shearing of axons and white matter tracts throughout the brain that result from rotational acceleration of the head.42 However, past ERP research could not examine the impacts of concussion on such diffuse networks within the brain because they employed low-density ERP systems with markedly fewer electrode-recording sites (64 electrodes or less). In contrast, the use of a 256-electrode high-density array significantly reduces interpolation errors between electrode sites and provides the most accurate source localization compared to models with fewer electrodes.43,44

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to use high-density ERPs and brain source localization (standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography; sLORETA)45 to investigate sensitive temporal and spatial changes to the brain associated with a history of concussion. Because of our increased spatial sampling (256 electrodes) and the documented positive relationship between scalp recordings and the occurrence of the BOLD response,46,47 we expect our amplitude/latency and source localization results to converge with the previously reviewed fMRI research, which reported that concussed athletes generated increased brain activation during cognitive tasks.34–37

We tested two main hypotheses. Hypothesis 1: Athletes with a history of concussion will generate increased P3b/N2 amplitudes and longer latencies compared to athletes without a past concussion. Hypothesis 2: Previously concussed athletes will generate increased ERP current density in inferior parietal and prefrontal brain areas (the sources for the P3b and the N2)48–50 compared to controls in the target and nontarget conditions, respectively.23,27,51

Methods

Participants

Forty-four NCAA Division I American male football athletes ranging in age from 18.32 to 23.30 years (20.52 ± 1.64) volunteered to participate and provided written consent. The institutional review board and athletic department at the host institution approved this study. All procedures were performed in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. Total test duration across all tasks was approximately 60 min. This included brief breaks between tasks. All athletes participated before the beginning of their fall athletic season. Data were collected over a period of 3 years. Athletes participating in the latter two years received $25 compensation.

Measures

Concussion history

A clinical practitioner-researcher determined athletes' past concussion history through a structured medical case history interview during pre-season health evaluations. Similar to other ERP research, participants self-reported the number of diagnosed concussions they experienced before testing.22,28,52–54 Athletes also reported the date of their most recent concussion and if any resulted in loss of consciousness or difficulty remembering events. In the case that participants did not complete a recent case interview at the host institution, past concussion history was determined from case history reports on their most recent ImPACT evaluation (ImPACT Applications, Pittsburgh, PA). Concussion severity information (loss of consciousness, memory problems) was not provided for 2 participants. Participants were only included in the concussion history group if they reported at least one diagnosed concussion. Time elapsed since most recent diagnosed concussed was calculated as the time (in months) between the approximate date of injury and the date of participation in the study.

Neuropsychological tests

Trained researchers administered three traditional paper-pencil neuropsychological tests that measured executive functioning abilities, including inhibition, mental flexibility, processing speed, task-switching, and working memory. EEG was not recorded during these tests.

Testing sequence

First, the oddball ERP task was administered. Then, the three neuropsychological tests were administered for approximately 15–20 min, with brief breaks after each test. Because the oddball task occurred before the neuropsychological tests, ERPs were not influenced by any mental or physical fatigue resulting from the neuropsychological tests.55 The three neuropsychological tests are described below.

Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Color-Word Interference

All participants completed the Color-Word Interference subtest of the D-KEFS Neuropsychological Battery (Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System).56 Data from 2 participants were removed from D-KEFS analyses because of color-blindness. Participants were presented with 50 color words (blue, red, and green) printed in congruent (e.g., blue in blue ink) or incongruent (e.g., blue in red ink) colors. The goal of this task was to verbally identify each word's ink color. Elapsed time to complete the test (ms) and errors (corrected, uncorrected) were recorded. Data were scaled to account for age. Performance on this test represents cognitive flexibility and inhibition.57

Trail-Making Test

Participants completed an adapted version of the Trail-Making Test Forms A and B.58 One participant was removed from Trail-Making analyses because of missing data. Two forms of the test were used. For Form A, the numbers 1–25 were placed in an array on a sheet of paper and participants connected the numbers in sequential order as fast as possible. Performance on Form A is thought to represent visual search speed.59 Form B consisted of numbers (1 to 12) and letters (A to L) organized in an array. Participants were instructed to connect the numbers to letters in sequential and alphabetical order (e.g., 1—A—2—B—3—C). Time elapsed to complete each form (ms) was recorded. Form B represents working memory, task-switching, and information processing speed.59,60

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV Letter-Number Sequencing

The Letter-Number Sequencing subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)-IV assesses attention, mental flexibility, and working memory.61 In this task, the administrator verbally presented sequences consisting of letters and numbers. The participants then repeated back the numbers in sequential order, starting from the lowest number and then repeated the letters in alphabetical order. The amount of items within each sequence increased throughout the task. Scores reflect the number of sequences correctly recalled. Data were scaled to account for each participant's age.

Two-tone auditory oddball task

Before the neuropsychological tests, participants completed a standard two-tone auditory oddball task during ERP recording to assess selective attention.62 Participants were seated in a dark room and centered in front of a standard Dell LCD 15.5” (39.5 cm) monitor. A speaker was placed 1 m behind and above the midline of the participant's head. Volume was adjusted such that stimulus loudness levels were matched at 80 dB SPL(A) when measured at the participant's ear. During the task, participants attended to a black screen that displayed a centered, white fixation cross. The fixation cross was viewed from a distance of 1 m with a visual angle of 0.46 degrees. Participants first completed four practice trials in which they heard each tone (1000 Hz, 1500 Hz) presented twice. Next, participants heard 100 random presentations of the two tones, which were classified as “target” (30%) and “nontarget” (70%) and counterbalanced across participants. The tones were presented every 1400–1600 ms using E-Prime software (version 2.0; Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Participants only responded to target tones by pressing a designated button on a handheld pad with their right thumb and their response time recorded. Accuracy was recorded for nontarget and target trials. Only correct responses were submitted to statistical analysis.

Event-related potential recording

Data collection and reduction

The ongoing EEG was recorded using a high-density Ag/AgCl 256-electrode net and Net Station software (version 4.4.2; Electro Geodesics Inc. [EGI], Eugene, OR). Sampling rate was 250 Hz. Electrode impedances were measured before and after the oddball task and maintained below 60 kΩ. No filters were imposed on the data during data collection. After data collection, EEG signals were band-passed filtered offline from 0.3 to 30 Hz. Correct trials were segmented to an epoch of 200 ms before each tone presentation and 900 ms post-stimulus onset. To control for brain changes related to increases in exposure to the stimuli throughout the testing session, we examined sequential pairs of target and nontarget trials: Correct target trials were only submitted to analyses if at least one of the two preceding trials included a nontarget. Similarly, correct nontarget trials were only included when at least one of the two following trials were targets. All signals were adjusted for computer timing offsets. Eye blinks were classified as a voltage shift greater than 150 uV at any electrode during any trial and were removed and replaced through spline interpolation from immediately adjacent electrodes. Next, trials were baseline-corrected using a 200-ms pre-stimulus period and rereferenced to the average reference. All trials were averaged within conditions (target, nontarget) for each electrode. To increase statistical power,63 the averaged ERPs were clustered into nine bilateral scalp regions: inferior frontal, inferior occipital, inferior temporal, occipital, orbital, parietal, prefrontal, tempoparietal, and temporal.64

Event-related potential brain source localization

Using all 256 electrode placements, we determined sources of brain localization that employed the sLORETA constraint45 within the GeoSource software package (version 2.0; EGI). A forward modeling approach mapped electrode scalp recordings onto brain tissue using a finite difference model (FDM). This method estimated the location of scalp electrodes in relation to the brain using conductivity values modeled for different tissues. Fixed conductivity parameters within the FDM included those for scalp (0.44 S/m), skull (0.018 S/m), cerebrospinal fluid (1.80 S/m), and brain (0.25 S/m).65 The FDM segmented brain tissue into 2-mm voxels, which were fit to the Montreal Neurological Institute's (MNI) 305-adult averaged MRI database. Gray matter volume was separated into 7-mm voxels based on this model and represents electrical current density (nA) in neuroanatomical MNI space. Each of these voxels served as a source location with three orthogonal dipole orientations for a total of 2447 orthogonal source triples. Dipole locations were weighted equally with a Tikhonov (1 × 10–2) regularization and a minimum norm solution that was constrained to sLORETA. Given our hypotheses, current density was analyzed during the P3b latency window for the target stimuli and the N2 latency window for the nontarget stimuli.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21; IBM, Chicago, IL). Reported results were statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. Effect sizes for significant analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were calculated using partial eta-squared and Cohen's d statistic for independent-samples t-tests. One-way ANOVAs determined whether performance on each of the three neuropsychological tests or oddball task (accuracy, response time) varied between groups. P3b adaptive mean amplitudes (μV) were extracted from a regional pool of parietal electrode channels throughout the 260- to 388-ms time window. This window is based on past research reporting a spatial-temporal principal component analysis factor in parietal electrode channels between 200 and 400 ms.66 Adaptive mean amplitude was defined as the mean ERP amplitude within the temporal window, including a two-sample (8-ms) adjustment before and after the window. Consistent with past work using a sample of college-aged athletes, the N2 ERP was recorded throughout the 150- to 300-ms time window,22 over prefrontal electrode channels. ERP latency was quantified as the time point of the maximum positive and negative deflections for the P3b and N2 time windows, respectively. Figure 1 depicts the P3b and N2 components by group and condition.

FIG 1.

Averaged ERP waveforms are represented by group (concussion history = gray; control = black) and condition (target = solid; nontarget = dashed). (A) P3b-positive amplitudes and latencies extracted from a regional average of parietal electrodes between 260 and 388 ms post-stimulus onset. (B) N2-negative amplitudes and latencies extracted from a regional average of pre-frontal electrodes between 150 and 300 ms post-stimulus onset. *p < 0.05. ERP, event-related potential.

Hypothesis 1 test

One-tailed independent-samples t-tests were used to test our first hypothesis that athletes in the concussion history group would exhibit larger P3b/N2 amplitudes and longer latencies compared to the control group.

Hypothesis 2 test

One-tailed independent-samples t-tests were also used to examine our second hypothesis that the concussion history group would exhibit greater current source localization in the parietal (P3b) and pre-frontal (N2) gyri compared to the control group.

Results

Concussion history assessment

Means and standard deviations of participant demographics and concussion history are reported in Table 1. Two groups comprised the sample. The concussion history group (n = 22) included athletes who reported experiencing at least one diagnosed concussion. The number of concussions reported ranged from 1 to 4 (mean = 1.59 ± 1.01). Approximately 32% of the athletes experienced more than one concussion. The time elapsed since most recent concussion ranged from approximately 4 months to 11 years (mean = 3.99 ± 3.81). The control group (n = 22) included athletes who reported never experiencing a diagnosed concussion. The ages of athletes in the two groups were equivalent (F(1, 42) = 0.44; p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Behavioral Performance by Group (Mean ± SD)

| Control (n = 22) | Conc. history (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20.69 ± 1.65 | 20.36 ± 1.64 |

| Previous concussions | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.59 ± 1.01* |

| Concussions with loss of consciousness | — | 0.55 ± 0.61* |

| Concussions with memory difficulties | — | 0.40 ± 0.50* |

| Time since most recent concussion (years) | — | 3.99 ± 3.81* |

| Neuropsychological performance | ||

| Trail-Making A (ms) | 18.96 ± 4.39 | 19.74 ± 5.68 |

| Trail-Making B (ms) | 45.24 ± 17.06 | 50.67 ± 19.48 |

| D-KEFS Color-Word Interference-Scaled (ms) | 11.0 ± 3.03 | 11.86 ± 2.10 |

| D-KEFS Color-Word Interference-Scaled (errors) | 9.19 ± 3.27 | 10.33 ± 2.75 |

| WAIS-Letter Number Sequencing-Scaled | 9.59 ± 2.30 | 10.05 ± 1.96 |

| Auditory Oddball | ||

| Accuracy—nontarget | 0.997 ± 0.01 | 0.991 ± 0.02 |

| Accuracy—target | 0.992 ± 0.02 | 0.980 ± 0.05 |

| Response time—target (ms) | 455.63 ± 114.20 | 472.55 ± 94.17 |

Group means and standard deviations for demographic variables and behavioral performance.

p < 0.05.

SD, standard deviation; D-KEFS, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; Conc., concussion.

Neuropsychological performance

Group performances for the neuropsychological tests and oddball task are reported in Table 1. There was no difference in performance between the concussion history and control groups on all neuropsychological tests (all ps > 0.05).

Two-tone auditory oddball

Behavioral response accuracy did not significantly differ between the concussion history and control groups for either the target or nontarget conditions (Fs(1, 42) ≤ 1.65; ps > 0.05). Groups also exhibited equivalent behavior response times to target trials (F(1, 42) = 0.29; p > 0.05).

Event-related potentials

The P3b component

Group-averaged ERP amplitudes and latencies for each condition are reported in Table 2. A one-way ANOVA yielded the expected “oddball” effect over parietal electrodes for the entire sample. Athletes generated significantly larger amplitudes to target trials (5.35 ± 2.08 μV) compared to nontarget trials (3.32 ± 1.76 μV; F(1, 86) = 24.33; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.22). Based on our hypotheses, planned comparisons specifically examined the effects of past concussion for the target condition. The concussion history group generated significantly larger P3b amplitudes (5.93 ± 2.02 μV) than the control group (4.76 ± 2.02 μV) for the target condition (t(42) = −1.93; p = 0.030; d = −0.58). Athletes' ERP latencies occurred significantly earlier to nontarget stimuli (314.95 ± 23.55 ms) than to targets (334.53 ± 23.77 ms; F(1, 86) = 15.07; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.15). Within the target condition, athletes with a past concussion (341.84 ± 18.93 ms) generated significantly longer latencies than controls (327.22 ± 26.20 ms; t(42) = −2.12; p = 0.020; d = −0.64).

Table 2.

ERP Amplitude and Latency Results by Group (Mean ± SD)

| Component | Control | Conc. history | t(42) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nontarget | ||||

| P3b amplitude | 3.16 ± 1.57 | 3.48 ± 1.96 | −0.60 | ns |

| P3b latency | 313.51 ± 25.61 | 316.40 ± 21.80 | −0.40 | ns |

| N2 amplitude | −2.77 ± 1.43 | −3.74 ± 1.71 | 2.05 | 0.023* |

| N2 latency | 222.65 ± 33.49 | 216.0 ± 41.10 | 0.59 | ns |

| Target | ||||

| P3b amplitude | 4.76 ± 2.02 | 5.93 ± 2.02 | −1.93 | 0.030* |

| P3b latency | 327.22 ± 26.20 | 341.84 ± 18.93 | −2.12 | 0.020* |

| N2 amplitude | −4.37 ± 2.10 | −4.01 ± 1.50 | −0.66 | ns |

| N2 latency | 233.10 ± 29.02 | 234.14 ± 24.31 | −0.13 | ns |

N2 and P3b amplitude and latency differences between groups for nontarget and target conditions.

p < 0.05.

ERP, event-related potential; SD, standard deviation; Conc., concussion; ns, not significant.

The N2 component

Targets elicited larger negative amplitudes (–4.19 ± 1.81 μV) than nontargets (−3.26 ± 1.63 μV; F(1, 86) = 6.41; p = 0.013; ηp2 = 0.07). Planned comparisons indicated that the concussion history group generated larger negative amplitudes to nontargets (−3.74 ± 1.71 μV) than controls (−2.77 ± 1.43 μV; t(42) = 2.05; p = 0.023; d = 0.62). N2 latencies occurred earlier for nontarget (219.32 ± 37.21 ms) than to target trials (233.62 ±26.46 ms; F(1, 86) = 4.31; p = 0.041; ηp2 = 0.05). Latency of the N2 component did not significantly differ between groups for the nontarget condition (t(42) = 0.59; p > 0.05).

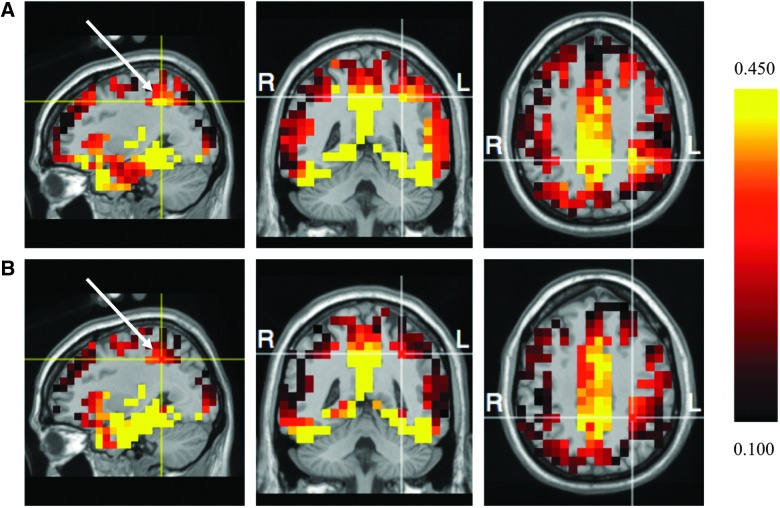

Event-related potential source localization

As illustrated in Figure 2, planned comparisons in the target condition indicated that current density within the P3b time window was greater for the concussion history group than controls in the left inferior parietal gyrus (t(42) = −3.35; p < 0.001; d = −1.01). Planned comparisons were performed on current density estimates in bilateral prefrontal gyri for the nontarget stimuli during the N2 window. Current density in prefrontal gyri did not significantly vary between groups (all ps > 0.05).

FIG 2.

Sagittal, coronal, and axial sections showing electrical current density maps (in nanoamp meters; nA) of the P3b component (target) for the (A) concussion history and (B) control groups. Current density patterns fit to the Montreal Neurological Institute's typical MRI head model. Cross-hairs intersect the left inferior parietal gyrus (xyz = −31, −46, 43; Brodmann area, 40) and indicate significant group differences (p < 0.001). Following radiological convention, the left hemispheres are presented on the right sides of each MRI model and the right hemispheres are presented on the left sides. L, left; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; R, right.

Discussion

Behavioral results

As expected, the concussion history and control groups performed equivalently on behavioral measures of executive function. This was reflected by comparable accuracy and response times on the oddball task and three neuropsychological tests that together examined mental flexibility, information processing speed, task-switching, and working memory. These results converge with the large body of research reporting that cognitive impairment measured on behavioral tests does not extend beyond 1 week post-concussion in the majority of athletes.6 Given such consistency in findings across studies, it appears that these neuropsychological tests are not sensitive enough to detect long-term cognitive impairments after a past concussion. However, in the current study, individuals with a past concussion (average of 4 years after the most recent) generated different electrophysiological responses compared to the control group. We must conclude that athletes with a past concussion are likely to generate altered, long-term neural patterns of attention, which certain neuropsychological tests are unlikely to detect.

Event-related potential findings

In support of hypothesis 1, athletes with a history of concussion generated delayed P3b latencies and an increase in P3b/N2 amplitudes during an oddball task. This finding disagrees with previous reports of decreased P3b amplitudes in individuals with a past concussion.22,51 Our findings more closely converge with those from fMRI reporting increases in brain activation patterns in brain-injured populations34–37 and the documented positive relationship between ERP recordings and BOLD response.46,47 We suggest that this larger P3b amplitude in athletes with a history of concussion represents an increase in resource allocation needed for context updating.15,19 The delayed P3b latency in previously concussed athletes converges with De Beaumont and colleagues, who reported delayed P3b latencies in a group of retired athletes who experienced their most recent concussion approximately 30 years before testing.52 Our current findings, when combined with De Beaumont and colleagues' results, reinforce the view that concussion is not a transient injury of short duration. Instead, concussion appears to impact the long-term state of neural networks that support stimulus evaluation speed.21 N2 amplitudes were larger in previously concussed athletes than controls in the nontarget condition. This finding extends previous work that reported larger N2 amplitudes to target stimuli in individuals with closed head injury and children with a TBI.29,30,67 It is possible that larger N2 amplitudes during the nontarget condition represent increased, but inefficient, neural processing supporting response inhibition and attentional alerting26,27 in previously concussed athletes.

Other researchers reported that a brain injury does not alter the latency of the P3b22,30 and that a decrease in P3b amplitudes follows concussion.22,51 However, the current results indicate that college athletes with a history of concussion generate increased P3b amplitudes and greater current density than controls. To explain these discrepancies, we propose two mechanisms at work.

First, decisions in ERP recording methods may contribute to our findings. We used high-density ERP recording in contrast to the more commonly used low-density systems that employ markedly fewer electrode channels. Low-density systems provide a greatly degraded view of spatially localized and distributed processes. Interpolation errors attributed to differences in spatial sampling are the primary difference between low- and high-density ERP recordings. A number of investigators have argued that employing electrode arrays with 128 channels or greater eliminates interpolation errors.43,68 Thus, our use of the 256 high-density electrode system (EGI) may provide a more optimal method to measure scalp potentials over the entire scalp and minimize error.63

We also measured ERP amplitudes and latencies from a regional average of electrode channels (see Fig. 1), rather than the more common approach of recording at one single electrode (e.g., Pz, Cz). There are several advantages to this regional electrode averaging method. First, adjacent electrode channels are likely to share variance, so averaging nearby electrodes leads to a more stable ANOVA model fit. Averaging adjacent electrodes also reduces potential errors from single-electrode recordings that may vary because of local fluctuations in scalp impedance and conductivity. In addition, regional averaging controls for the inflated degrees of freedom inherent in recordings from multiple single electrodes.70 We recommend that future researchers consider using this regional averaging approach based on scalp topography64 in order to reduce electrode recording errors and type 1 error inflation rates.

Second, individuals with a past concussion invariably must recruit and reallocate additional neural mechanisms to meet current task demands. Molfese provided a hypothesis of cognitive development that advances this point.40 According to this view, increasingly efficient neural networks support cognitive development. That is, throughout the learning process, fewer and fewer neural mechanisms are required to support a cognitive task. However, a concussion disrupts the operation of this neural network. To moderate this dysfunction, additional spatially distributed brain mechanisms are recruited to compensate for degraded processing efficiency post-injury. This invariably leads to longer processing time because more areas and pathways are engaged. In line with this hypothesis, P3b/N2 amplitude increases and P3b latency delays in concussed athletes may reflect this greater, albeit inefficient, recruitment of additional brain processes to perform the oddball task. To further investigate this hypothesis, we used source localization methods to identify the distribution of neural sources underlying ERPs.

Source localization findings

Current density during the P3b window was greater in the left inferior parietal gyrus (IPG) for the concussion history group than control athletes. In contrast to our second hypothesis, current density in prefrontal gyri underlying the N2 component was not greater in individuals with a history of concussion.

The IPG is involved in the dorsal frontoparietal network supporting the top-down processing of endogenous attention.71 Findings from fMRI research on individuals with a past mTBI converge with our source localization findings of a disrupted dorsal frontoparietal network.32,36 The IPG is also implicated in working memory,72 suggesting that this structure may support early attentional processes necessary to keep cognitive mechanisms “online” in order to selectively attend to stimuli. As indicated by increased P3b amplitudes, longer latencies, and increased current density in the left IPG, athletes with a past concussion may allocate additional neural resources in order to selectively attend to target stimuli and update working memory.15,73 We propose that this neural network underlying attention and working memory is likely disrupted post-injury.

The current ERP amplitude/latency and source localization findings converge with fMRI results used to hypothesize that concussed/TBI individuals demonstrate compensatory neural recruitment patterns during cognitive tasks.34,35,39,40 Using fMRI, Slobonouv and colleagues also found that college athletes with a recent concussion exhibited increased neural networks of activation while encoding a spatial memory navigation map compared to a control group.74 However, other studies reported that individuals with mTBI generated decreased BOLD signal in the right dlPFC while engaging in working memory compared to control groups.31,32 Whether these conflicting results between fMRI studies are attributed to differences in sampling (e.g., time post-concussion, age of participants) or methodology (e.g., task demands) remains in question.

Other results lend themselves to an “altered connectivity” hypothesis that functional connectivity between brain areas is altered post-TBI. One such study used resting-state sLORETA and graph theory analysis to map changes in functional connectivity in college athletes 7 days post-mTBI.75 These researchers reported that, compared to their baseline, athletes exhibited increased “short-distance” connectivity between occipital and parietal lobes, but decreased connectivity between frontal lobes and more distal regions of the brain. Other research used similar structural equation modeling techniques to examine functional connectivity within and between hemispheric neural networks during varying loads of a working memory task (i.e., 1-back, 2-back) in individuals who experienced a moderate or severe TBI.76 In this study, functional connectivity within the right pre-frontal cortex (PFC) decreased throughout the 1-back task in both TBI and healthy individuals, suggesting that these networks processed information more efficiently. At moderate working memory loads (2-back), right PFC connectivity decreased for healthy individuals throughout the task, but not the TBI group. Therefore, consistent with other theories of neural connectivity,40 neural networks supporting working memory may become increasingly efficient with repeated task exposure. However, individuals who experienced a TBI may fail to develop increasingly efficient neural networks to support task completion.

Although the current results favor a “reorganization/compensation” hypothesis, we posit that several theories may together explain the atypical neural network connectivity and brain responses associated with concussion. For example, functional connectivity after a concussion may decrease between distal brain areas,75 increase between shorter paths,75,76 and also may influence hyperactive/compensatory brain activity.34,36,74 It is critical for research to consider integrating multiple theoretical perspectives to accurately represent functional connectivity and brain activation patterns in individuals with a past concussion.

The current findings indicate that athletes with past concussion generate atypical brain patterns supporting attentional processes. However, these marked differences in electrophysiological processing were not indicated in athletes' performance on three neuropsychological tests. Therefore, these altered brain responses underlying attention may lead to subtle variations in information processing and resource allocation supporting top-down control that are not shown on standard accuracy/reaction time tasks. However, such altered brain responses may lead to overt functional consequences under greater task demands, particularly for college football athletes. For example, research reported that individuals with mTBI performed slower than controls on a dual-task measure of attention, but not under single-task demands.77 This finding is important to consider given the multiple task demands that college football players simultaneously experience during competition (e.g., awareness of own and opponents' body positions, avoiding distractions, and attending to moment-to-moment changes in physiological phenomena) and everyday life.

The current findings are also critical for understanding the long-term impact of neural differences in concussed athletes on functional behavior, given their similarity to studies on both normative and pathological aging. In their seminal study, Guskiewicz and colleagues reported a positive relationship between the number of past concussions in retired athletes and the likelihood of being diagnosed with an MCI.10 This relationship between concussion and subsequent development of cognitive impairment may provide a link between studies on concussion and aging, which report similar findings. Specifically, athletes in the current study with a concussion history generated larger P3b/N2 amplitudes, delayed P3b latencies, and greater current density in the IPG than controls—findings that are also reported in the aging literature. For example, healthy older adults generated greater P3 amplitudes, delayed latencies, and increased parietal lobe activity during working memory compared to younger adults.78,79 The current findings also converge with pathological aging research that reported smaller left IPG volume in adults with MCI.80 Taken together, these findings led some researchers to suggest that the experience of a concussion may exacerbate the cognitive aging process.14 To investigate this question, future research is necessary to examine the causal link between the experience of concussion(s) and functional brain activity across the adult life span.

Limitations

It is possible that between-group differences in amplitude and latency of the P3b/N2 complex and source localization results were attributed to individual differences related to the nature of athletes' experience of past concussive events. Factors influencing the ERP morphology may include: number/severity of past concussions; the extent to which time elapsed since most recent concussion; time between concussive events; and return to play time after the event. For example, during a visual search task, college athletes with a history of multiple concussions generated altered P3 amplitudes compared to those with a single or no past concussion.23 However, P3 amplitude was not significantly related to the time elapsed since most recent concussion, nor the number of times athletes experienced a concussion with loss of consciousness or anterograde/retrograde amnesia. Future research should employ larger sample sizes to continue to explore the extent to which brain responses supporting attention differ between groups of athletes with multiple concussions and/or varying time elapsed since most recent concussion. In addition, athletes' self-report of their history and approximate date of diagnosed concussion limits our study. Physician- or trainer-documented concussions in an active athlete may be an underestimate of the number actually experienced. In fact, some researchers suggest that approximately 50% of concussions go unreported.81 Therefore, future research should collect medical documentation of diagnosed concussions. Research should also consider including athletes participating in noncontact sports in their investigations. This would provide an additional comparison group of athletes who are unlikely to experience the repetitive head impacts inherent in contact sports. A cross-sectional design also prevents us from concluding that a past concussion caused the P3b/N2 amplitude, latency, and source localization effects. A cross-sequential design might be a much more effective approach in future research.

Conclusion

Our study reports that there are long-term cognitive impairments associated with concussion. During a two-tone auditory oddball task, college football athletes with a history of concussion exhibited increased P3b and N2 amplitudes and longer P3b latencies compared to teammates never diagnosed with a concussion. Differences in sources of electrical current density between groups indicated that athletes with a history of concussion exhibited greater current density within the left IPG. We conclude that increased cortical activity in athletes with a past concussion may result from an inefficient, compensatory recruitment of neural resources needed to meet cognitive demands. These electrophysiological findings were evident an average of 4 years after athletes' most recent concussion. However, athletes with and without a past concussion did not differ in their performance on traditional tests of neuropsychological function. Therefore, these neuropsychological tests do not appear to have the sensitivity to detect the long-term cognitive impairments associated with a history of concussion. We conclude that high-density ERPs and brain source localization (sLORETA) may provide a more optimal method for examining the long-term impact of concussion on functional brain activity.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by funding from The National Institutes of Health (1R01EB007684).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Langlois J.A., Rutland-Brown W., and Wald M.M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harmon K.G., Drezner J.A, Gammons M., Guskiewicz K.M., Halstead M., Herring S.A., Kutcher J.S., Pana A., Putukian M., and Roberts W.O. (2013). American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 23, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covassin T., Swanik C.B., and Sachs M.L. (2003). Epidemiological considerations of concussions among intercollegiate athletes. Appl. Neuropsychol. 10, 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein E.A., Corso P.S., and Miller T.R. (2006). The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. Oxford University Press: New York [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broglio S.P., and Puetz T.W. (2008). The effect of sport concussion on neurocognitive function, self-report symptoms and postural control: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 38, 53–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrea M., Guskiewicz K.M., Marshall S.W., Barr W., Randolph C., Cantu R.C., Onate J.A., Yang J., and Kelly J. P. (2003). Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA. 290, 2556–2563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field M., Collins M.W., Lovell M.R., and Maroon J. (2003). Does age play a role in recovery form sports-related concussion? A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes. J. Pediatr. 142, 546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broglio S.P., Ferrara M.S., Piland S.G., and Anderson R.B. (2006). Concussion history is not a predictor of computerised neurocognitive performance. Br. J. Sports Med. 40, 802–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iverson G.L., Brooks B.L., Lovell M.R., and Collins M. W. (2006). No cumulative effects for one or two previous concussions. Br. J. Sports Med. 40, 72–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guskiewicz K.M., Marshall S.W., Bailes J., McCrea M., Cantu R.C., Randolph C., and Jordan B.D. (2005). Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Neurosurgery 57, 719–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guskiewicz K.M., Marshall S.W., Bailes J., McCrea M., Harding H.P., Jr., Matthews A., Mihalik J.R., and Cantu R. C. (2007). Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 39, 903–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jellinger K.A., Paulus W., Wrocklage C., and Litvan I. (2001). Traumatic brain injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Comparison of two retrospective autopsy cohorts with evaluation of the ApoE genotype. BMC Neurol. 1, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee A., Cantu R., Nowinski C.J., Hedley-Whyte E.T. Gavett B.E., Budson A.E., Santini V.E., Lee H.S., Kubilis C.A., and Stern R.A. (2009). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy following repetitive head injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68, 709–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broglio S.P., Moore R.D., and Hillman C.H. (2011). A history of sport-related concussion on event-related brain potential correlates of cognition. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 82, 16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donchin E., and Coles M.G. (1988). Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behav. Brain Sci. 11, 357–374 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton S., Braren M., Zubin J., and John E.R. (1965). Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science 150, 1187–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donchin E., Karis D., Bashore T.R., Coles M.G., and Gratton G. (1986). Cognitive psychophysiology and human information processing, in: Psychophysiology: Systems, Processes, and Applications. Coles M.G., Donchin E., and Porges S.W. (eds). Guilford: New York, pps. 244–267 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson R., Jr. (1993). On the neural generators of the P300 component of the event-related potential. Psychophysiology 30, 90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polich J. (2007). Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin. Neurophysiol. 118, 2128–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polich J. (1986). Attention, probability, and task demands as determinants of P300 latency from auditory stimuli. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 63, 251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan-Johnson C.C. (1981). Young Psychologist Award address, 1980. P300 latency: a new metric of information processing. Psychophysiology 18, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broglio S.P., Pontifex M.B., O'Connor P., and Hillman C.H. (2009). The persistent effects of concussion on neuroelectric indices of attention. J. Neurotrauma 26, 1463–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Beaumont L., Brisson B., Lassonde M., and Jolicoeur P. (2007). Long-term electrophysiological changes in athletes with a history of multiple concussions. Brain Inj. 21, 631–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavoie M.E., Dupuis F., Johnston K.M., Leclerc S., and Lassonde M. (2004). Visual p300 effects beyond symptoms in concussed college athletes. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 26, 55–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Key A.P., Dove G.O., and Maguire M.J. (2005). Linking brainwaves to the brain: an ERP primer. Dev. Neuropsychol. 27, 183–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein J.R., and Van Petten C. (2008). Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology 45, 152–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jodo E., and Kayama Y. (1992). Relation of a negative ERP component to response inhibition in a Go/No-go task. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophsyiol. 82, 477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore R.D., Hillman C.H., and Broglio S.P. (2014). The persistent influence of concussive injuries on cognitive control and neuroelectric function. J. Athl. Train. 49, 24–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore R.D., Pindus D.M., Drolette E.S., Scudder M.R., Raine L.B., and Hillman C.H. (2015). The persistent influence of pediatric concussion on attention and cognitive control during flanker performance. Biol. Psychol. 109, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rugg M.D., Cowan C.P., Nagy M.E., Milner A.D., Jacobson I., and Brooks D.N. (1988). Event related potentials from closed head injury patients in an auditory “oddball” task: evidence of dysfunction in stimulus categorization. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 51, 691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J.K., Johnston K.M., Frey S., Petrides M., Worsley K., and Ptito A. (2004). Functional abnormalities in symptomatic concussed athletes: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 22, 68–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witt S.T., Lovejoy D.W., Pearlson G.D., and Stevens M.C. (2010). Decreased prefrontal cortex activity in mild traumatic brain injury during performance of an auditory oddball task. Brain Imaging Behav. 4, 232–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAllister T.W., Saykin A.J., Flashman L.A., Sparling M.B., Johnson S.C., Guerin S.J., Mamourian A.C., Weaver J.B., and Yanofsky N. (1999). Brain activation during working memory 1 month after mild traumatic brain injury: a functional MRI study. Neurology 53, 1300–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAllister T.W., Sparling M.B., Flashman L.A., Guerin S.J., Mamourian A.C., and Saykin A.J. (2001). Differential working memory load effects after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage 14, 1004–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pardini J.E., Pardini D.A., Becker J.T., Dunfee K.L., Eddy W.F., Lovell M.R., and Welling J.S. (2010). Postconcussive symptoms are associated with compensatory cortical recruitment during a working memory task. Neurosurgery 67, 1020–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jantzen K.J., Anderson B., Steinberg F.L., and Kelso J.A. (2004). A prospective functional MR imaging study of mild traumatic brain injury in college football players. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 25, 738–745 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer A.R., Yang Z., Yeo R.A., Pena A., Ling J.M., Mannell M.W., Stippler M., and Mojtahed K. (2012). A functional MRI study of multimodal selective attention following mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reuter-Lorenz P.A., and Cappell K.A. (2008). Neurocognitive aging and compensation hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 17, 177–182 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ricker J.H., Hillary F.G., and DeLuca J. (2001). Functionally activated brain imaging (O-15 PET and fMRI) in the study of learning and memory after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 16, 191–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molfese D.L. (2015). The need for theory to guide concussion research. Dev. Neuropsychol. 40, 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Povlishock J.T., and Katz D.I. (2005). Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 20, 76–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith D.H., Meaney D.F., and Shull W.H. (2003). Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 18, 307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Junghöfer M., Elbert T., Leiderer P., Berg P., and Rockstroh B. (1997). Mapping EEG potentials on the surface of the brain: a strategy for uncovering cortical sources. Brain Topogr. 9, 203–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song J., Davey C., Poulsen C., Turovets S., Luu P., and Tucker D.M. (2014). Sensor density and head surface coverage in EEG source localization, in: 2014 IEEE 11th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2014) IEEE: New York, pps. 620–623 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pascual-Marqui R.D. (2002). Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 24 Suppl. D, 5–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brázdil M., Dobšick M., Mikl M., Hluštik P., Daniel P., Pažourková M., Krupa P., and Rektor I. (2005). Combined event-related fMRI and intracerebral ERP study of an auditory oddball task. Neuroimage 26, 285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juckel G., Karch S., Kawohl W., Kirsch V., Jäger L., Leicht G., Lutz J., Stammel A., Pogarell O., Ertl M., Reiser M., Hegerl U., Möller H.J., and Mulert C. (2012). Age effects on the P300 potential and the corresponding fMRI BOLD-signal. Neuroimage 60, 2027–2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathalon D.H., Whitfield S.L., and Ford J.M. (2003). Anatomy of an error: ERP and fMRI. Biol. Psychol. 64, 119–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulert C., Pogarell O., Juckel G., Rujescu D., Giegling I., Rupp D., Mavrogiorgou P., Bussfield P., Gallinat J., Möller H.J., and Hegerl U. (2004). The neural basis of the P300 potential: focus on the time-course of the underlying cortical generators. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 254, 190–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volpe U., Mucci A., Bucci P., Merlotti E., Galderisi S., and Maj M. (2007). The cortical generators of P3a and P3b: a LORETA study. Brain Res. Bull. 73, 220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dupuis F., Johnston K.M., Lavoie M., Lepore F., and Lassonde M. (2000). Concussions in athletes produce brain dysfunction as revealed by event-related potentials. Neuroreport 11, 4087–4092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Beaumont L., Théoret H., Mongeon D., Messier J., Leclerc S., Tremblay S., Ellemberg D., and Lassonde M. (2009). Brain function decline in healthy retired athletes who sustained their last sports concussion in early adulthood. Brain 132, 695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore R.D., Broglio S.P., and Hillman C.H. (2014). Sport-related concussion and sensory function in young adults. J. Athl. Train. 49, 36–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ozen L.J., Itier R.J., Preston F.F., and Fernandes M.A. (2013). Long-term working memory deficits after concussion: electrophysiological evidence. Brain Inj. 27, 1244–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barwick F., Arnett P., and Slobounov S. (2012). EEG correlates of fatigue during administration of a neuropsychological test battery. Clin. Neurophsyiol. 123, 278–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delis D.C., Kaplan E., and Kramer J.H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS). The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimoska-Di Marco A., McDonald S., Kelly M., Tate R., and Johnstone S. (2011). A meta-analysis of response inhibition and Stroop interference control deficits in adults with traumatic brain injury (TBI). J. Clinical Exp. Neuropsychol. 33, 471–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reitan R.M., and Wolfson D. (1988). The Halstead–Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Neuropsychology Press: Tucson, AZ [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sánchez-Cubillo I., Periáñez J.A., Adrover-Roig D., Rodríguez-Sánchez J.M., Ríos-Lago M., Tirapu J., and Barceló F. (2009). Construct validity of the Trail Making Test: role of task-switching, working memory, inhibition/interference control, and visuomotor abilities. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 15, 438–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collie A., Makdissi M., Maruff P., Bennell K., and McCrory P. (2006). Cognition in the days following concussion: comparison of symptomatic versus asymptomatic athletes. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77, 241–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wechsler D. (2008). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV). NCS Pearson: San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson R., Jr. (1989). Auditory and visual P300s in temporal lobectomy patients: evidence for modality-dependent generators. Psychophysiology 26, 633–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Curran T. (1999). The electrophysiology of incidental and intentional retrieval: ERP old/new effects in lexical decision and recognition memory. Neuropsychologia 37, 771–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kota S., Kelsey K.M., Rigoni J.B., and Molfese D.L. (2013). Feasibility of using event-related potentials as a sideline measure of neurocognitive dysfunction during sporting events. Neuroreport 24, 437–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferree T., Eriksen K.J., and Tucker D.M. (2000). Region head tissue conductivity estimation for improved EEG analysis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 47, 1584–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spencer K.M., Dien J., and Donchin E. (1999). A componential analysis of the ERP elicited by novel events using a dense electrode array. Psychophysiology 36, 409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Curry S.H. (1980). Event-related potentials as indicants of structural and functional damage in closed head injury, in: Motivation, Motor and Sensory Processes of the Brain: Electrical Potentials, Behaviour and Clinical Use. Kornhuber H.H. and Deeke L. (eds). Elsevier: Amsterdam, pps. 507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Srinivasan R., Tucker D.M., and Murias M. (1998). Estimating the spatial Nyquist of the human EEG. Behav. Res. Methods 30, 8–19 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tucker D.M. (1993). Spatial sampling of head electrical fields: the geodesic sensor net. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 87, 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dien J., and Santuzzi A.M. (2005). Application of repeated measures ANOVA to high-density ERP datasets: a review and tutorial, in: Event Related Potentials: A Methods Handbook. Handy T. (ed). MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, pps. 57–82 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corbetta M., and Shulman G.L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Owen A.M., McMillan K.M., Laird A.R., and Bullmore E. (2005). N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 25, 46–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donchin E. (1981). Presidential address, 1980. Surprise! … Surprise? Psychophysiology 18, 493–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Slobounov S.M., Zhang K., Pennell D., Ray W., Johnson B., and Sebastianelli W. (2010). Functional abnormalities in normally appearing athletes following mild traumatic brain injury: a functional MRI study. Exp. Brain Res. 202, 341–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cao C., and Slobounov S.M. (2010). Alteration of cortical functional connectivity as a result of traumatic brain injury revealed by Graph Theory, ICA and sLORETA analyses of EEG signals. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 18, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hillary F.G., Medaglia J.D., Gates K., Molennar P.C., Slocomb J., Peechatka A., and Good D.C. (2011). Examining working memory task acquisition in a disrupted neural network. Brain 134, 1555–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cicerone K.D. (1996). Attention deficits and dual task demands after mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 10, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cabeza R., Daselaar S.M., Dolcos F., Prince S.E., Budde M., and Nyberg L. (2004). Task independent and task-specific age effects on brain activity during working memory, visual attention and episodic retrieval. Cereb. Cortex 14, 364–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saliasi E., Geerligs L., Lorist M.M., and Maurits N.M. (2013). The relationship between P3 amplitude and working memory performance differs in young and older adults. PLoS One 8, e63701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greene S.J., and Killiany R.J.; and Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2010). Subregions of the inferior parietal lobule are affected in the progression to Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 31,1304–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCrea M., Hammeke T., Olsen G., Leo P., and Guskiewicz K. (2004). Unreported concussion in high school football players: implications for prevention. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 14, 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]