Abstract

Objective:

In this study, the human absorbed dose of holmium-166 (166Ho)-pamidronate (PAM) as a potential agent for the management of multiple myeloma was estimated.

Methods:

166Ho-PAM complex was prepared at optimized conditions and injected into the rats. The equivalent and effective absorbed doses to human organs after injection of the complex were estimated by radiation-absorbed dose assessment resource and methods proposed by Sparks et al based on rat data. The red marrow to other organ absorbed dose ratios were compared with these data for 166Ho-DOTMP, as the only clinically used 166Ho bone marrow ablative agent, and 166Ho-TTHMP.

Results:

The highest absorbed dose amounts are observed in the bone surface and bone marrow with 1.11 and 0.903 mGy MBq−1, respectively. Most other organs would receive approximately insignificant absorbed dose. While 166Ho-PAM demonstrated a higher red marrow to total body absorbed dose ratio than 166Ho-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclo dodecane-1,4,7,10 tetra ethylene phosphonic acid (DOTMP) and 166Ho-triethylene tetramine hexa (methylene phosphonic acid) (TTHMP), the red marrow to most organ absorbed dose ratios for 166Ho-TTHMP and 166Ho-PAM are much higher than the ratios for 166Ho-DOTMP.

Conclusion:

The result showed that 166Ho-PAM has significant characteristics than 166Ho-DOTMP and therefore, this complex can be considered as a good agent for bone marrow ablative therapy.

Advances in knowledge:

In this work, two separate points have been investigated: (1) human absorbed dose of 166Ho-PAM, as a potential bone marrow ablative agent, has been estimated; and (2) the complex has been compared with 166Ho-DOTMP, as the only clinically used bone marrow ablative radiopharmaceutical, showing significant characteristics.

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, radiopharmaceuticals have widespread applications in the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases.1,2 The skeleton is one of the most common sites of metastases in several tumours such as prostate (80%), breast and lung carcinomas (50%).3 On the other hand, multiple myeloma, as a fatal illness arising from plasma cells in the bone marrow, is an aggressive plasma cell malignancy that can entail an occurrence of progressive pain.4 Multiple myeloma presents with symptoms related to anaemia, hypercalcemia, fatigue, bone pain and renal dysfunction.5

For patients with mentioned morbidities, phosphonate ligands labelled with beta-emitting particles have comprehensive usage in nuclear medicine. (3-amino-1-hydroxypropane-1,1-di-yl)-bis(phosphonate), pamidronate (PAM), a multidentate polyaminopolyphosphonic acid ligand, can be considered as a possible carrier moiety for the development of beta emitter-based radiopharmaceuticals. PAM is used to prevent osteoporosis and bone loss in certain cancers including multiple myeloma in clinical trials. Also, the existence of an amino group in this ligand could possibly increase the complex stability. Biological half-life for PAM (28.7 h) and holmium-166 (166Ho) physical half-life (27 h) demonstrate interesting compatible radionuclide–ligand couple for developing a possible radiopharmaceutical.6

Among different beta emitter radionuclides like 32P, 89Sr, 90Y, 153Sm and 186Re proposed as alternative modalities for the management of bone pain,7 166Ho, owing to its beta particle energy (Eβmax = 1.84 MeV), has considerable potential for delivering ablative radiation doses to the bone marrow in multiple myeloma. Therefore, some phosphonate ligands labelled with 166Ho such as 166Ho-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclo dodecane-1,4,7,10 tetra ethylene phosphonic acid (DOTMP),8,9 166Ho-ethylenediaminetetramethylene phosphonic acid (EDTMP)10,11 and 166Ho-N,N-dimethylenephosphonate-1-hydroxy-3-aminopropylidenediphosphonate (APDDMP)12 are developed and found to be suitable complexes for bone marrow ablation.

One of the most important parameters in the administration of radiopharmaceuticals is the absorbed dose, as the amount of energy deposited in unit mass of any organ by ionizing radiation, delivered to each organ. This concern is naturally heightened in therapy applications, where a significant absorbed dose may be received by other organs and in particular radiosensitive organs.13 So, the knowledge of the radiation-absorbed doses to various critical organs, especially the bone marrow, liver, kidney and spleen, is important for considering the maximum of injecting activity.14

Estimation of the organ radiation exposure dose can be released from biodistribution data in small animals, such as rats, to humans and it is a prerequisite for the clinical application of a new radiopharmaceutical.15 In fact, prior to moving forward with human measurements from a small number of volunteers, consistent with the recommendations of International Commission on Radiological Protection 62,16 this estimation is a common step for accelerating the development of radioactive compounds in clinical applications. Absorbed dose estimates in small animals are conventionally derived by sacrificing the animals at various times points after tracer administration, harvesting and weighing their organs and measuring their respective activities.17,18

Four methods have been introduced by Spark et al for extrapolating animal uptake data to equivalent uptake in humans.19 In the first one, it is considered that the percentage of the injected activity at any time in the human and animal organ is the same. In the relative organ mass extrapolation and the physiological time extrapolation, as in other methods, the mass and time coefficients are used to convert the animal uptake data to human ones, respectively. In the last proposed method, the relative organ mass and the physiological time extrapolation techniques are combined.

Internal dose assessment depends on the use of mathematical formulas for dose calculation and models of the human body and its organs. The first values for dose factors were published in medical internal radiation dosimetry (MIRD) Pamphlet No. 11 in 1975 for dosimetric calculations in nuclear medicine. Recently, new models have been employed by updating dose factors for the bone and marrow, with suggested corrections. Nowadays, the most commonly used procedure for the calculation of the internal dose estimates is the radiation-absorbed dose assessment resource (RADAR) method.20

Owing to the special characteristics of 166Ho and PAM, 166Ho-PAM has been recently synthesized, showing good characteristics such as significant accumulation in the bone tissue and inconsiderable uptake in other organs.8 The utilization possibility of 166Ho-PAM as the new bone ablative agent is related to the absorbed dose delivered to the bone marrow as the target organ with regard to the other organ absorbed dose. In this study, 166Ho-PAM complex was prepared and injected into rats. The absorbed dose to human organs after injection of the complex was estimated by RADAR method. The resulting data were compared with 166Ho-DOTMP, as the only clinically used 166Ho bone marrow ablative agent, and 166Ho-triethylene tetramine hexa (methylene phosphonic acid) (TTHMP).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Production of 166Ho was performed at a research reactor using 165Ho(n,γ) 166Ho nuclear reaction. Natural holmium nitrate with a purity of >99.99% was obtained from ISOTEC Inc. All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (UK). Whatman No. 1 paper was obtained from Whatman (UK). Radiochromatography was performed by Whatman paper using a thin-layer chromatography scanner (Bioscan AR2000, Eckert & Ziegler Radiopharma Inc., Paris, France). The activity of the samples was measured by a p-type coaxial high-purity germanium (HPGe) detector (model: EGPC 80–200R) coupled with a multichannel analyzer system. Calculations were based on the 80.6-keV peak for 166Ho. All values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and the data were compared using Student's t-test. Animal studies were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Biological Council's Guidelines on the Use of Living Animals in Scientific Investigations (2nd edn, Institute of Biology, London, 1987).

Production and quality control of 166HoCl3 solution

166Ho was produced by neutron irradiation of 100 µg of natural 165Ho(NO3)3 (165Ho with a purity of 99.99% from ISOTEC Inc.) in a research reactor with a thermal neutron flux of 5 × 1013 N cm−2 s−1. Specific activity of the produced 166Ho was 7.5 GBq mg−1 after 2 days of irradiation. The irradiated target was dissolved in 200 μl of 1.0 M HCl to prepare 166HoCl3 and diluted to the appropriate volume with ultrapure water to produce a stock solution. The mixture was filtered through a 0.22-μm biological filter and sent for use in the radiolabelling step. The radionuclidic purity of the solution was tested for the presence of other radionuclides using beta spectroscopy as well as HPGe spectroscopy for the detection of various interfering beta- and gamma-emitting radionuclides. The radiochemical purity of the 166HoCl3 was checked by means of two solvent systems for RTLC (A—10-mM DTPA with pH 4 and B—ammonium acetate 10%: methanol (1 : 1)).

Preparation and quality control of 166Ho-PAM

The radiolabelling of PAM was performed according to the previously reported procedure.8 Briefly, a stock solution of monosodium pamidronic acid salt (molecular weight 257) was prepared by dissolution in double-distilled ultrapure water to produce a solution of 50 mg mL−1. 5 mCi of the 166HoCl3 solution was added to 0.3 ml of NaPAM solution. The complex solutions were kept at room temperature for 60 min. The radiochemical purity was determined using instant thin layer chromatography (ITLC) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods. The best ITLC mobile phase was considered as NH4OH : MeOH : H2O (0.2 : 2:4) mixture. The final solution was passed through a 0.22-µm membrane filter and the pH was adjusted to 7.5 with 0.05-mol.L−1 phosphate buffer.

Biodistribution study of 166Ho-PAM in rats

The distribution of radiolabelled complex (2, 4, 24 and 48 h) among tissues was determined in the rats. The total amount of radioactivity injected into each animal was measured by counting the syringe before and after injection in a dose calibrator with fixed geometry. The radioactivity was injected intravenously to the rats through their tail vein. The animals were sacrificed using the animal care protocols at select times after injection. The tissues were weighed and rinsed with normal saline, and their activities were determined with a p-type coaxial HPGe detector coupled with a multichannel analyzer according to Equation (1):21

| (1) |

where, ε is the efficiency at photopeak energy, γ is the emission probability of the gamma line corresponding to the peak energy, ts is the live time of the sample spectrum collection in seconds, m is the mass (in kilograms) of the measured sample and k1, k2, k3, k4 and k5 are the correction factors for the nuclide decay from the time the sample is collected to the start of the measurement, the nuclide decay during counting period, self-attenuation in the measured sample, pulse loss due to random summing and the coincidence, respectively. N is the corrected net peak area of the corresponding photopeak given as:

| (2) |

where Ns is the net peak area in the sample spectrum, Nb is the corresponding net peak area in the background spectrum and tb is the live time of the background spectrum collection in seconds.

The percentage of the injected dose per gram for different organs was calculated by dividing the amount of activity for each tissue (A) to the non-decay-corrected injected activity and the mass of each organ. Four rats were sacrificed for each interval. All values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and the data were compared using Student's t-test.

Calculation of accumulated activity in human organs

The accumulated source activity for animal organs was calculated by plotting the non-decay-corrected percentage-injected dose vs time according to Equation (3):

| (3) |

where A(t) is the activity of each organ at time t.

For this purpose, linear approximation was used between the two experimental points of time. The curves were extrapolated to infinity by fitting the tail of each curve to a monoexponential curve with the exponential coefficient equal to the physical decay constant of 166Ho. The activity of blood at t = 0 was considered as the total amount of the injected activity, and the activity of all other organs was estimated to be zero at that time.

The accumulated activity for animal organs was then extrapolated to the accumulated activity for human organs by the proposed method of Sparks et al (Equation 4).19

| (4) |

For this extrapolation, the standard mean weights of human organs were used.7

Equivalent absorbed dose calculation

The absorbed dose in human organs was calculated by RADAR formalism based on biodistribution data in the rats:19

| (5) |

where à is the accumulated activity for each human organ and DF is:

| (6) |

In this equation, ni is the number of radiations with energy E emitted per nuclear transition, Ei is the energy per radiation (in megaelectron volts), φi is the fraction of energy emitted that is absorbed in the target, m is the mass of the target region (in kilograms) and k is some proportionality constant . DF represents the physical decay characteristics of the radionuclide, the range of the emitted radiations and the organ size and configuration,22 expressed in milligray per megabecquerel seconds. In this research, DFs have been taken from the amounts presented in OLINDA/EXM software.23

Since D in Equation (5) is the absorbed dose in the target organ received from a source organ, the total absorbed dose for each target organ was computed by the summation of the absorbed dose delivered from each source organ.

Effective absorbed dose calculation

The effective absorbed dose was computed by the following equation (Equation (7)):

| (7) |

where HT is the equivalent absorbed dose for each organ and WT is the tissue-weighting factor which represents a subjective balance between the different stochastic health risks.24 The amounts of WT were obtained from the reported values in International Commission on Radiological Protection 103.25

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Production and quality control of 166HoCl3 solution

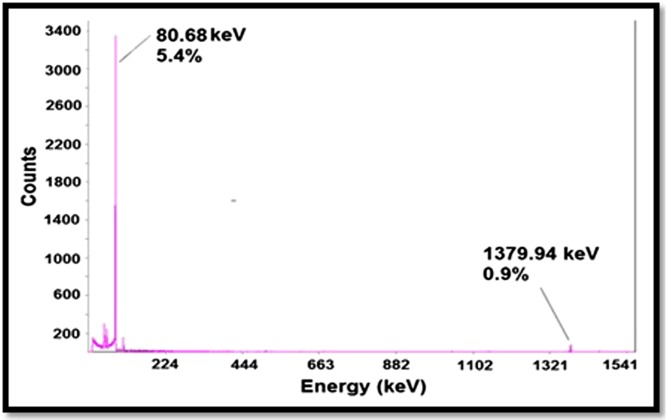

166Ho was prepared in a research reactor with a range of specific activity of 3–5 MBq mg−1. Two major photons (5.4% of 80.68 keV and 0.9 % of 1379.94 keV) were observed owing to counting the samples on an HPGe detector for 5 min. The radionuclidic purity was calculated to be higher than 99% (Figure 1). The radiochemical purity of the166Ho solution was checked by two solvents: 10-mmol L−1 DTPA solution (Solvent 1) and 10 % ammonium acetate: methanol mixture (1 : 1) (Solvent 2), showing an amount of purity of >99%.

Figure 1.

Gamma spectrum of 166HoCl3 solution used for labelling.

Preparation and quality control of 166Ho-PAM

166Ho-PAM was obtained at the optimized conditions with a radiochemical purity of higher than 99%. 166Ho3+ would stay approximately at the origin of the Whatman paper in NH4OH : MeOH : H2O (0.2 : 2 : 4) solution as the best mobile phase, while 166Ho-PAM complex migrates to the higher retention factor. Also, the HPLC chromatograms of 166Ho-PMD on a reversed phase column using acetonitrile:water 40 : 60 proved the result of ITLC.

Dosimetric studies

Owing to the strong affinity for binding of bisphosphonates to hydroxyapatite as the main component of the inorganic matrix of the bone,26 this drug class in labelling with therapeutic radionuclides can be considered as an effective agent for bone pain palliation or bone marrow ablation. Besides, one of the most important challenges in developing new agents for radiation therapy is to deliver an adequate dose of ionizing radiation to the target organ, while the absorbed dose of the non-target organs should be kept as low as possible. Therefore, the knowledge of the radiation dose received by different organs in the body is essential for an evaluation of the risks and benefits of any procedure.13

While radionuclides with a low beta particle energy are recommended for bone pain palliation as they have approximately insignificant effects on the bone marrow,27 those with higher energies are appropriate for bone marrow ablation. 166Ho is one of the suitable radionuclides that can be used for bone marrow ablation owing to its high beta particle energy. On the other hand, its physical half-life (26.8 h) is short enough to permit delivery of high-dose chemotherapy and reinfusion of cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cells within 6–10 days.9

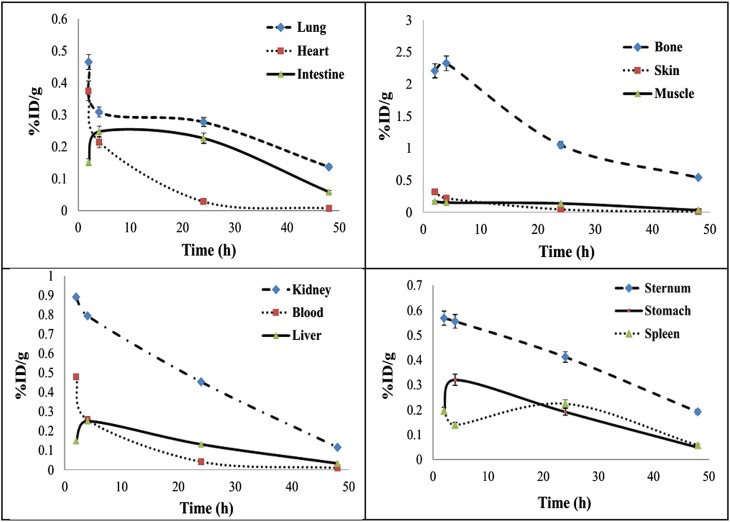

In this study, dosimetric calculations of 166Ho-PAM complex were performed using the RADAR method based on the biodistribution data related to the rat organs. The non-decay-corrected activity curves are demonstrated in Figure 2. Also, the equivalent and effective absorbed doses in human organs after i.v. injection of 166Ho-PAM are presented in Table 1. As expected, the highest absorbed dose amounts are observed in the bone surface and bone marrow with 1.11 and 0.903 mGy MBq−1, respectively. Most other organs would receive approximately insignificant absorbed dose.

Figure 2.

Non-decay-corrected clearance curves for rat organs after i.v. injection of 166Ho-pamidronate. % ID/g, percentage of the injected dose per gram.

Table 1.

Equivalent and effective absorbed doses delivered into human organs after injection of 166Ho-pamidronate

| Target organs | Equivalent absorbed dose in humans (mGy/MBq) | Tissue weighting factor (Wta) | Effective absorbed dose in humans (mSv/MBq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenals | 0.003 | 0.12 | 0.0004 |

| Brain | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.0000 |

| Breasts | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| GB wall | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| LLI wall | 0.208 | 0.12 | 0.0250 |

| Small intestine | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Stomach wall | 0.027 | 0.12 | 0.0032 |

| ULI wall | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Heart wall | 0.038 | 0.12 | 0.0046 |

| Kidneys | 0.157 | 0.12 | 0.0188 |

| Liver | 0.063 | 0.04 | 0.0025 |

| Lungs | 0.075 | 0.12 | 0.0090 |

| Muscle | 0.062 | 0.12 | 0.0074 |

| Ovaries | 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.0002 |

| Pancreas | 0.002 | 0.12 | 0.0002 |

| Red Marrow | 0.903 | 0.12 | 0.1110 |

| Bone surf | 1.11 | 0.01 | 0.0114 |

| Spleen | 0.068 | 0.12 | 0.0082 |

| Testes | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Thymus | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Thyroid | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.0001 |

| UB wall | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.0000 |

| Total body | 0.095 | 0.203 |

GB, gallbladder; LLI, lower large intestine; UB, urinary bladder; ULI, upper large intestine.

Tissue-weighting factors according to International Commission on Radiological Protection 103 (2007).

The most important goal in developing therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals is to deliver the maximum possible dose to the target organ and the minimum possible dose to the non-target organs. Therefore, the target to non-target absorbed dose ratios are important parameters that should be considered. The bone marrow to other organ absorbed dose ratios after injection of the 166Ho-PAM are given in Table 2. For better comparison, these ratios for the 166Ho-DOTMP complex, as the only clinically used 166Ho bone marrow ablative agent, and 166Ho-TTHMP, as the other agent introduced for this purpose, are presented in the table too.

Table 2.

Bone marrow to non-target absorbed dose ratios for 166Ho-pamidronate (PAM), 166Ho-DOTMP9 and 166Ho-TTHMP7

| Organs | 166Ho-PAM | 166Ho-DOTMP | 166Ho-TTHMP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenals | 308.3 | 36.9 | 379 |

| Brain | 308.3 | 36.9 | 337.7 |

| Breasts | 925 | 39.8 | 1241.2 |

| GB wall | 925 | 39.8 | 977.1 |

| LLI wall | 4.4 | 36.9 | 20.5 |

| Small intestine | 925 | 39.8 | 761.3 |

| Stomach wall | 34.3 | 39.8 | 85.1 |

| ULI wall | 925 | 39.8 | 886.5 |

| Heart wall | 24.3 | 39.8 | 63.9 |

| Kidneys | 5.9 | 11.5 | 7.3 |

| Liver | 14.7 | 39.8 | 46.9 |

| Lungs | 12.3 | 36.9 | 22.4 |

| Muscle | 14.9 | 39.8 | 56.2 |

| Pancreas | 462.5 | 39.8 | 647.5 |

| Red marrow | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bone surf | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Spleen | 13.6 | 39.8 | 21.3 |

| Testes | 925 | 39.8 | 1268.1 |

| Thymus | 925 | 39.8 | 876.2 |

| Thyroid | 462.5 | 36.9 | 568.9 |

| UB wall | 925 | 1.8 | 1201.3 |

| Total body | 9.5 | 8.3 | 9.3 |

GB, gallbladder; LLI, lower large intestine; UB, urinary bladder; ULI, upper large intestine.

While 166Ho-PAM demonstrated a higher red marrow to total body absorbed dose ratio than 166Ho-DOTMP and 166Ho-TTHMP, the red marrow to the most organ absorbed dose ratios for 166Ho-TTHMP and 166Ho-PAM are much higher than the ratios for 166Ho-DOTMP. This means that for a certain dose to the red marrow as the target organ, the total body would receive a lesser absorbed dose in the case of 166Ho-PAM utilization. The red marrow to kidney and lung (as two critical organs) absorbed dose ratios are greater for 166Ho-DOTMP than that for 166Ho-TTHMP and 166Ho-PAM. Therefore, for a given dose to the red marrow, these organs would receive lesser absorbed dose in the case of 166Ho-DOTMP usage. Also, the absorbed dose ratio of the red marrow to liver for 166Ho-TTHMP is higher than the ratios for the other two complexes.

CONCLUSION

In this study, 166Ho-PAM complex was prepared in high radiochemical purity (>99%, ITLC and HPLC). The final preparation was administered to the rats and biodistribution of the complex was checked 2–48 h post-injection. The absorbed dose of human organs was estimated according to the RADAR and methods proposed by Spark et al. The results showed that approximately all tissues would receive insignificant absorbed dose in comparison with the bone tissue (Table 2). The comparison of 166Ho-PAM with 166Ho-DOTMP and 166Ho-TTHMP demonstrated that this complex has remarkable characteristics than 166Ho-DOTMP, as the only clinically used bone marrow ablative radiopharmaceutical, and therefore can be considered as a good agent for bone marrow ablative therapy.

Contributor Information

Mahdokht Vaez-Tehrani, Email: ihjb87@yahoo.com.

Samaneh Zolghadri, Email: s_zolghadri63@yahoo.com.

Hassan Yousefnia, Email: hyousefnia@aeoi.org.ir.

Hossein Afarideh, Email: hasanyousefnia@yahoo.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Turner PG, O'Sullivan JM. (223)Ra and other bone-targeting radiopharmaceuticals-the translation of radiation biology into clinical practice. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20140752. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo FI, Proença FP, Ferreira CG, Ventilari SC, Rosado de Castro PH, Moreira RD, et al. Use of (99m)Tc-doxorubicin scintigraphy in females with breast cancer: a pilot study. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20150268. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serafini AN. Therapy of metastatic bone pain. J Nucl Med 2001; 42: 895–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Owen RG, Bell SE, Hawkins K, et al. ; Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1875–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitz H, Wendt R, Stabin M, Bouchet L, Wessels B. Dosimetry of high dose skeletal targeted radiotherapy (STR) with 166Ho-DOTMP. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2003; 18: 225–30. doi: 10.1089/108497803765036391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakhari A, Jalilian AM, Yousefnia H, Johari-Daha F, Mazidi M, Khalaj A. Development of 166Ho-pamidronate for bone pain palliation therapy. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2015; 303: 743–50. doi: 10.1007/s10967-014-3515-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousefnia H, Zolghadri S, Jalilian AR, Tajik M, Ghannadi-Maragheh M. Preliminary dosimetric evaluation of (166)Ho-TTHMP for human based on biodistribution data in rats. Appl Radiat Isot 2014; 94: 260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagheri R, Jalilian AR, Bahrami-Samani A, Mazidi M, Ghan-nadi-Maragheh M. Production of Holmium-166 DOTMP: A promising agent for bone marrow ablation in hematologic malignancies. Iran J Nucl Med 2011; 19: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breitz HB, Wendt RE, Stabin MS, Shen S, Erwin WD, Raj-endrann JG, et al. 166Ho-DOTMP radiation-absorbed dose estimation for skeletal targeted radiotherapy. J Nucl Med 2006; 47: 534–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahrami-Samani A, Bagheri R, Jalilian AR, Shirvani-Arani S, Ghannadi-Maragheh M, Shamsaee M. Production, quality control and pharmacokinetic studies of Ho-EDTMP for therapeutic applications. Sci Pharm 2010; 78: 423–33. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1004-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louw WK, Dormehl IC, van Rensburg AJ, Hugo N, Alberts AS, Forsyth OE, et al. Evaluation of samarium-153 and holmium-166-EDTMP in the normal baboon model. Nucl Med Biol 1996; 23: 935–40. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(96)00117-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeevaart JR, Jarvis NV, Louw WK, Jackson GE. Metal-ion speciation in blood plasma incorporating the tetraphosphonate, N,N-dimethylenephosphonate-1-hydroxy-4-aminopropilydenediphosphonate (APDDMP), in therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals. J Inorg Biochem 2001; 83: 57–65. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(00)00125-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stabin MG, Tagesson M, Thomas SR, Ljungberg M, Strand SE. Radiation dosimetry in nuclear medicine. Appl Radiat Isot 1999; 50: 73–87. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(98)00023-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallabhajosula S, Kuji I, Hamacher KA, Konishi S, Kostakoglu L, Kothari PA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of 111In- and 177Lu-labeled J591 antibody specific for prostate-specific membrane antigen: prediction of 90Y-J591 radiation dosimetry based on 111In or 177Lu? J Nucl Med 2005; 46: 634–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kesner AL, Hsueh WA, Czernin J, Padgett H, Phelps ME, Silverman DH. Radiation dose estimates for [18F]5-fluorouracil derived from PET-based and tissue-based methods in rats. Mol Imaging Biol 2008; 10: 341–8. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0160-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICRP Publication 62. Radiological Protection in Biomedical Research. Annals of the ICRP. Vol. 22/3: International Commission on Radiological Protection; 1993. [PubMed]

- 17.Tang G, Wang M, Tang X, Luo L, Gan M. Pharmacokinetics and radiation dosimetry estimation of O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine as oncologic PET tracer. Appl Radiat Isot 2003; 58: 219–25. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00311-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGrado TR, Baldwin SW, Wang S, Orr MD, Liao RP, Friedman HS, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of (18)F-labeled choline analogs as oncologic PET tracers. J Nucl Med 2001; 42: 1805–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparks RB, Aydogan B. Comparison of the effectiveness of some common animal data scaling techniques in estimating human radiation dose. Sixth International Radiopharmaceutical Dosimetry Symposium. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge Associated Universities; 1996. pp. 705–16. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stabin MG, Siegel JA. Physical models and dose factors for use in internal dose assessment. Health Phys 2003; 85: 294–310. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200309000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IAEA-TECDOC-1401. Quantifying uncertainty in nuclear analytical measurements. Vienna: IAEA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bevelacqua JJ. Internal dosimetry primer. Radiat Prot Manage 2005; 22: 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stabin MG, Sparks RB, Crowe E. OLINDA/EXM: the second-generation personal computer software for internal dose assessment in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med 2005; 46: 1023–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner DJ. Effective dose: a flawed concept that could and should be replaced. Br J Radiol 2008; 81: 521–3. doi: 10.1259/bjr/22942198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann ICRP 2007; 37: 1–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousefnia H, Amraee N, Hosntalab M, Zolghadri S, Bahrami-Samani A. Preparation and biological evaluation of 166Ho-BPAMD as a potential therapeutic bone-seeking agent. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2015; 304: 1285–91. doi: 10.1007/s10967-014-3924-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchet LG, Bolch WE, Goddu SM, Howell RW, Rao DV. Considerations in the selection of radiopharmaceuticals for palliation of bone pain from metastatic osseous lesions. J Nucl Med 2000; 41: 682–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]