Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the sensitivity and robustness of a volumetric breast density (VBD) measurement system to errors in the imaging physics parameters including compressed breast thickness (CBT), tube voltage (kVp), filter thickness, tube current-exposure time product (mAs), detector gain, detector offset and image noise.

Methods:

3317 raw digital mammograms were processed with Volpara® (Matakina Technology Ltd, Wellington, New Zealand) to obtain fibroglandular tissue volume (FGV), breast volume (BV) and VBD. Errors in parameters including CBT, kVp, filter thickness and mAs were simulated by varying them in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) tags of the images up to ±10% of the original values. Errors in detector gain and offset were simulated by varying them in the Volpara configuration file up to ±10% from their default values. For image noise, Gaussian noise was generated and introduced into the original images.

Results:

Errors in filter thickness, mAs, detector gain and offset had limited effects on FGV, BV and VBD. Significant effects in VBD were observed when CBT, kVp, detector offset and image noise were varied (p < 0.0001). Maximum shifts in the mean (1.2%) and median (1.1%) VBD of the study population occurred when CBT was varied.

Conclusion:

Volpara was robust to expected clinical variations, with errors in most investigated parameters giving limited changes in results, although extreme variations in CBT and kVp could lead to greater errors.

Advances in knowledge:

Despite Volpara's robustness, rigorous quality control is essential to keep the parameter errors within reasonable bounds. Volpara appears robust within those bounds, albeit for more advanced applications such as tracking density change over time, it remains to be seen how accurate the measures need to be.

INTRODUCTION

Breast density is the term commonly used to refer to the percentage of the breast which is composed of fibroglandular tissue compared with adipose (fat) tissue. That percentage can be assessed visually from a mammogram, in which case, we get an area-based percentage which approximately equates to the percentage of the projected breast area covered by a significant amount of dense tissue, where the “significant” part is left to the radiologists to decide. Alternatively, the percentage can be computed volumetrically, in which case, we get a true, physical estimate of what tissues the breast contains and the total volume of the breast.

Area-based percentages have been shown to have strong relationships to the risk of breast cancer developing1–5 and to the risk of breast cancer being missed in mammograms.6–9 The data for volumetric measures are still being collected; previous studies have reported that early implementations were very sensitive to errors in the reported physics factors10–12 and the risk results are disappointing,13 but more recent implementations have found more promising results.14–16 The basic assumption behind volumetric techniques is that the breast consists of fat and fibroglandular tissue and that we can use X-ray physics parameters for each image to estimate X-ray attenuation between each pixel and the X-ray source, hence, the various contributions of those tissue types between that pixel and the X-ray source. Where volumetric technique differs is in the implementation used to get to the volumetric measures.

The first attempts at volumetric breast density (VBD) were reported by Highnam17 in 1992 in which he showed pictures of film mammograms alongside estimates of VBD and performed a sensitivity analysis in which he used simple monoenergetic assumptions to model errors in the input physics parameters to see the effect on the final VBD. Highnam and Brady10 found that a 1 mm error in compressed breast thickness (CBT) can lead to a shift of about ±4% in VBD estimation, which is large since VBDs are typically around 20%.10–12,18 That initial work was based on absolute physics models which required accuracy in all the physics parameters recorded by the machine into the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) image tags and in parameters such as detector gain which is not recorded on a per image basis.

Recently, with the increasing use of full-field digital mammography, further volumetric implementations have been suggested, which include:

Putting a calibration device into the image in order to not rely on all the physics parameters.14,19–22 These techniques have shown some promising results, but questions remain around robustness and clinical utility, especially when imaging large breasts, as the calibration device needs to be removed.

Using a calibration device on a daily basis to calibrate the physics,23 but such techniques still rely heavily on accuracy of the physics parameters such as breast thickness on an image-by-image basis.

Determination of a fat reference point in the image, such as that suggested by van Engeland et al24 who developed a relative physical model based on the work of Highnam and Brady.10

Tromans and Brady25 reported results on quantifying breast tissues on mammograms using their standard attenuation rate algorithm which was developed based on an absolute physical model of image formation, although robustness and clinical utility have not been investigated.

More recently, Ding and Molloi26 reported quantifying breast density using a photon-counting spectral mammography system with their multislit spectral detector. Results based on computer simulation model, phantom and post-mortem breast studies seem promising;26,27 although robustness and clinical utility have not been fully investigated.

Ideally, VBD measurement methods should produce objective, reproducible and reliable results. However, early absolute-physics volumetric techniques depend excessively on the imaging physics parameters recorded during image acquisitions (which were assumed to be accurate), and they were plagued by errors in the physics calibration data leading to large errors in the VBD.10,18,28,29 For example, the lack of consistent guidelines on breast compression leads to variations in the CBT.30,31 Given that even the US Mammography Quality Standards Act and Program requires CBT scale accurate only to within ±5 mm,32 there is clearly scope for huge errors in the volumetric measures. Other factors which may lead to variations in the physics parameters include the use of tilting paddles, age of the image detectors and mammography systems, poor system calibrations, changes in the ambient temperature, and patients' condition.

Recently, with the automation of breast density measurement tools which enables them to work in high-throughput conditions, there has been a widespread use of such tools in assessing breast density and its association with breast cancer risk.33–37 Examples of automated VBD measurement systems which are available commercially include Quantra (Hologic, Bedford, MA) and Volpara® (Matakina Technology Ltd, Wellington, New Zealand). From previous studies, it appears Quantra38 is based on the work of Highnam and Brady,10 and Volpara18 appears to be a further implementation of that original work along with ideas from van Engeland et al.24 Results vs breast MRI appear to suggest that volumetric techniques are now approaching clinical utility,39–42 but no thorough sensitivity and robustness analyses appear to have been carried out, to the best of our knowledge, except the one reported by Volpara developers during its early stage of development.18 Owing to the widespread use of breast density and recent legislative activities in the USA where the laws require females to be informed about their breast density in the mammographic report, it is important that breast density measurement tools are able to provide accurate, consistent and reliable results. In this study, we analysed the sensitivity and robustness of Volpara, which its developers claim always uses a reference point of fat, and thus always apply a relative model of physics rather than an absolute model which they claim is far more clinically robust.18

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study subjects and digital mammograms

We retrospectively collected “For Processing” raw digital mammographic images, including both craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views, for the females who underwent screening or diagnostic mammography at our centre between January 2013 and December 2014 from the three different manufacturer mammography systems at our centre, namely, GE Essential (GE, North Greenbush, NY), Siemens Novation (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and Hologic Selenia (Hologic, Bedford, MA). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Malaya Medical Centre (reference no. 1031.13), Malaysia. Since all the images and data used in this study were anonymized and no personal identifying information was used, the need for informed consent was waived by the committee.

All the images collected were first processed with Volpara v. 1.5.1 to obtain the volumetric density measures, i.e. fibroglandular tissue volume (FGV), breast volume (BV), VBD and Volpara density grade (VDG 1, 2, 3 and 4 which correlate with the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System density categories a, b, c and d, respectively) for each study.43

The volumetric density measures obtained from the original images including FGV, BV, VBD and VDG per study were assumed to be the “ground truth” values. We used Python v. 2.7 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE) scripts to process and change the imaging physics parameters including CBT, tube voltage (kVp), filter thickness and tube current–exposure time product (mAs) and to add image noise to the original images. The Python scripts are available in Appendix A. For CBT, kVp, filter thickness and mAs, simulation of errors was performed by varying the parameters in the DICOM tags up to ±10% from their original values. For the simulation of image noise, a pseudorandom number generator for Gaussian distribution available from the Python package was used to generate Gaussian noise.44 The Gaussian noise generated was then added to the original images. The probability density of the Gaussian distribution is given by Equation (1), where x is the variable, µ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation.44 Although different sets of µ and σ values could be used for generating Gaussian noise, they were chosen such that the image quality of the noise-added images was still within diagnostic quality. 50 of these noise-added images were randomly selected for image quality inspection and were compared with the corresponding original images by a radiographer. All the 50 images must be within diagnostic quality to be considered acceptable. This is considered to be a sufficient image quality check in this case, since in a real clinical setup, images which are noisy and beyond diagnostic quality, will be rejected in the first place.

| (1) |

More details of the Python Gaussian noise generator are available in SciPy.org.44 For detector gain and offset, the corresponding values in the Volpara configuration file for the three manufacturers, i.e. GE, Siemens and Hologic, were varied up to ±10% from their default values. Each time, only one parameter was altered from the original value, and the modified images were then processed with Volpara for the volumetric and VDG results. Effects of error in each parameter were then observed, and results were compared with the “ground truth” values.

Volumetric breast density assessment

The VBD assessment system investigated in this study, Volpara v. 1.5.1, is automated and based around an entirely “relative physics” model given in Equation (2).18,24 Technical details of Volpara have previously been reported.18 In brief, consider a typical digital mammographic image and Equation (2). To find the thickness of dense tissue (hd) between each pixel (x,y) on the image and the X-ray source, Volpara algorithm uses a region in the breast on the detector that corresponds to entirely fat tissue as a reference level (Pfat).18,24

| (2) |

The pixel value (P) is assumed to be linearly related to the energy imparted to the X-ray detector. µfat and µdense are the effective X-ray linear attenuation coefficients for fat and dense tissue, respectively, at particular target, filter, kVp, mAs and CBT combination. Dense tissue volume was derived by integrating hd(x,y) over the image, whereas BV is derived by multiplying the breast area by CBT with proper adjustments for the breast edge.18 VBD is then computed from the ratio of these two volumes.

Volpara reports VBD typically ranging from 0% to 35%, where the density excludes the skin. Besides FGV, BV and VBD, Volpara also provides VDG results with VBD of 0–4.5% graded as VDG 1, 4.5–7.5% as VDG 2, 7.5–15.5% as VDG 3 and 15.5% and above as VDG 4.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the subjects' age and volumetric measurement results across the three manufacturer mammography systems were used to summarize the study population and breast density data. Since the data were not normally distributed, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were also calculated besides the means and standard deviations (SDs). Scatter plots were used to visualize the comparison between volumetric measures per study obtained from the original images and images processed after each parameter was modified. Spearman's correlation coefficients were calculated from the relationships of volumetric measures per study between the original images and images after each parameter modification. The volumetric measures per breast were first obtained by averaging available data of the CC and MLO views for each breast, respectively. Volumetric measures per study were then calculated by averaging volumetric data of the left and right breasts for each subject. In order to determine whether VBD from the images processed with Volpara after each parameter modification were significantly different from the corresponding “ground truth” values obtained from the original images, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, with p < 0.05 deemed significant. In addition, linearly weighted kappa statistic was used to determine the consistency or agreement between the VDG results from the original images and those obtained from the images with each parameter change. Weighted kappa of 0.00–0.20 was interpreted as slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 was interpreted as fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 was interpreted as moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 was interpreted as substantial agreement and 0.81–1.00 was interpreted as almost perfect agreement. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® software v. 16.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and MedCalc® for Windows® v. 12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

RESULTS

A total of 3317 “For Processing” digital mammographic images (including CC and MLO views) from 915 females were retrospectively collected for this study with 1106 images from 305 females acquired on the GE Essential system, 1108 images from 305 females acquired on the Siemens Novation system and 1103 images from 305 females acquired on the Hologic Selenia system. Not every female has all the four standard mammographic view images available. The mean ± SD, median and IQR for the subjects' age are 57 ± 10 years, 57 years and 14 years, respectively. The mean ± SD, median and IQR for the FGV are 52.3 ± 34.5 cm3, 43.2 cm3 and 31.1 cm3, respectively. The mean ± SD, median and IQR for BV are 588.6 ± 358.3 cm3, 525.4 cm3 and 405.2 cm3, respectively. The mean ± SD, median and IQR for the VBD are 10.5 ± 5.8%, 8.9% and 7.2%, respectively. The descriptive statistics of the subjects' age, volumetric density measures and VDG across the three manufacturer mammography systems are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and volumetric density measures for the study population

| Subject characteristics/volumetric density measures | Overall (N = 915) |

GE Essential (North Greenbush, NY) (n = 305) |

Siemens Novation (Erlangen, Germany) (n = 305) |

Hologic Selenia (Bedford, MA) (n = 305) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median | IQR | Mean ± SD | Median | IQR | Mean ± SD | Median | IQR | Mean ± SD | Median | IQR | |

| Age (years) | 57 ± 10 | 57 | 14 | 57 ± 10 | 57 | 15 | 57 ± 9 | 57 | 14 | 57 ± 10 | 56 | 14 |

| FGV (cm3) | 52.3 ± 34.5 | 43.2 | 31.1 | 56.3 ± 35.6 | 45.9 | 38.1 | 47.8 ± 33.9 | 39.8 | 28.5 | 52.6 ± 33.4 | 44.0 | 32.5 |

| BV (cm3) | 588.6 ± 358.3 | 525.4 | 405.2 | 599.3 ± 372.4 | 534.7 | 420.6 | 600.2 ± 361.0 | 528.0 | 420.0 | 565.8 ± 340.5 | 499.6 | 395.8 |

| VBD (%) | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 10.9 ± 5.6 | 9.7 | 7.3 | 9.3 ± 5.3 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 11.2 ± 6.3 | 9.4 | 7.9 |

BV, breast volume; FGV, fibroglandular tissue volume; IQR, interquartile range; N, total number of subject; n, number of subject in each subgroup; SD, standard deviation; VBD, volumetric breast density.

Table 2.

Volpara density grade (VDG) for the study population

| VDG | Overall (N = 915) |

GE Essential (North Greenbush, NY) (n = 305) |

Siemens Novation (Erlangen, Germany) (n = 305) |

Hologic Selenia (Bedford, MA) (n = 305) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 1 | 103 | 11.3 | 26 | 8.5 | 53 | 17.4 | 24 | 7.9 |

| 2 | 250 | 27.3 | 73 | 23.9 | 101 | 33.1 | 76 | 24.9 |

| 3 | 391 | 42.7 | 146 | 47.9 | 107 | 35.1 | 138 | 45.2 |

| 4 | 171 | 18.7 | 60 | 19.7 | 44 | 14.4 | 67 | 22.0 |

N, total number of subject; n, number of subject in each subgroup.

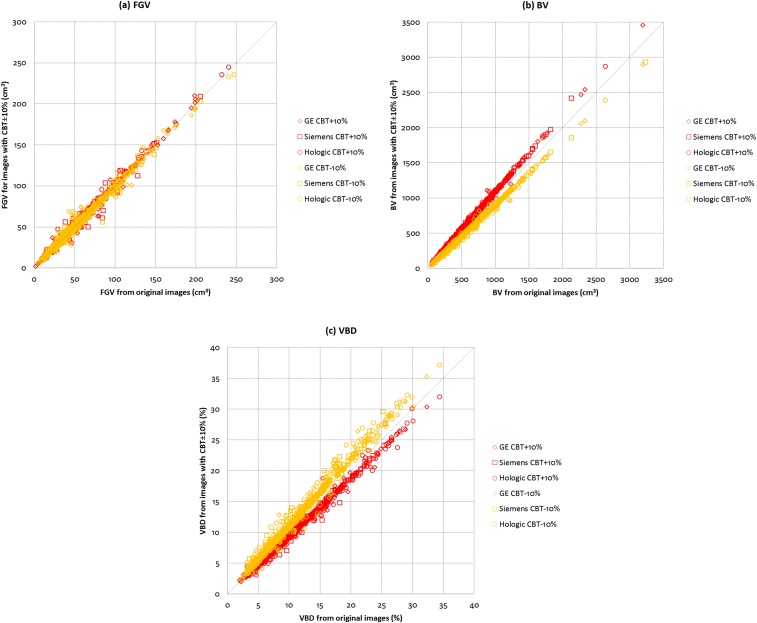

Figure 1 shows the relationships between the original and CBT-modified images for (a) FGV, (b) BV and (c) VBD across the three manufacturer mammography systems. For CBT varied by +10%, correlations are 0.99, 1.00 and 0.99 for FGV, BV and VBD, respectively. For CBT varied by −10%, correlations are all 0.98 for FGV, BV and VBD. Data show that variations in CBT have limited effect on FGV. However, it was observed that variations in CBT have the opposite effects on BV as compared with VBD. When CBT increases, BV also increases with the effect being more prominent in larger breasts, whereas VBD decreases with the effect being more prominent in denser breasts, and vice versa for the case when CBT decreases. When CBT was varied by +10%, the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects shifted to 9.7 ± 5.4% and 8.3%, respectively. When CBT was varied by −10%, the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects shifted to 11.7 ± 6.5% and 10.0%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Comparisons between original and compressed breast thickness (CBT)-modified images for (a) fibroglandular volume (FGV), (b) breast volume (BV) and (c) VBD across the three manufacturer mammography systems (N = 915).

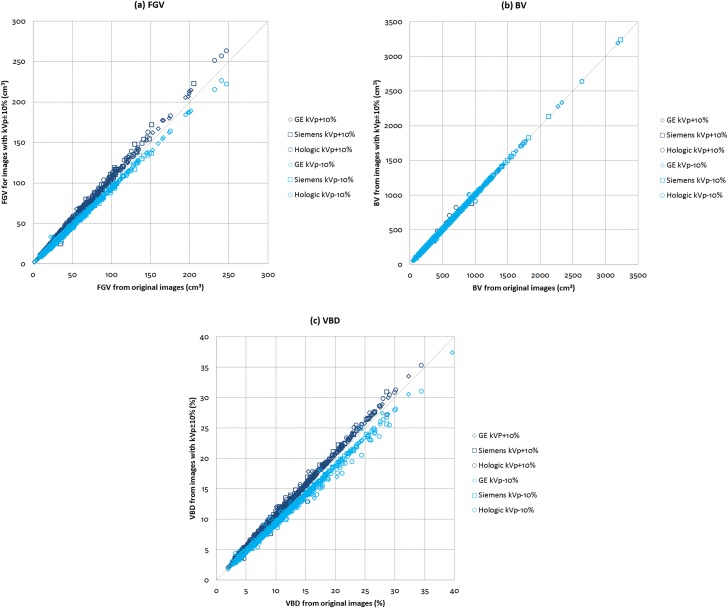

The relationships between the original and kVp-modified images for (a) FGV, (b) BV and (c) VBD across the three manufacturer mammography systems are shown in Figure 2. For kVp varied by ±10%, correlations are all 1.00 for FGV, BV and VBD. Our data show that variations in kVp have no effect on BV. On the other hand, variations in kVp have similar effects on FGV and VBD. When kVp increases, FGV and VBD also increase with the effect being more prominent in larger and denser breasts, and vice versa for the case when kVp decreases. When kVp was varied by +10%, the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects shifted to 11.0 ± 6.0% and 9.4%, respectively. When kVp was varied by −10%, the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects shifted to 9.7 ± 5.4% and 8.3%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparisons between original and tube voltage (kVp)-modified images for (a) fibroglandular volume (FGV), (b) breast volume (BV) and (c) volumetric breast density (VBD) across the three manufacturer mammography systems (N = 915).

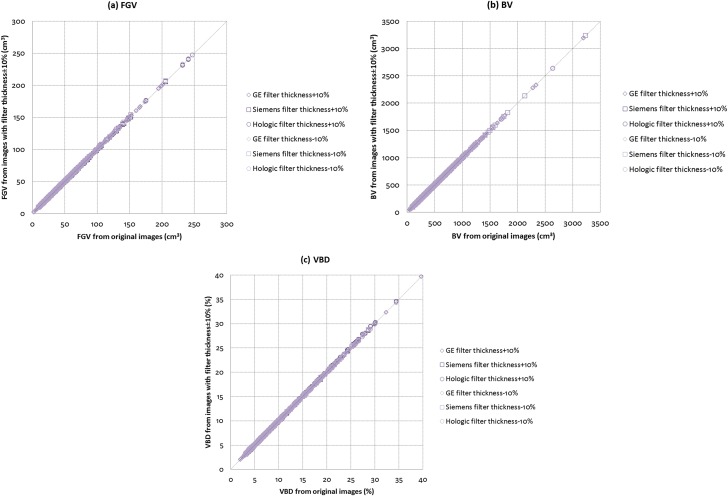

Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between the original and filter thickness-modified images for (a) FGV, (b) BV and (c) VBD across the three manufacturer mammography systems. For filter thickness varied by ±10%, correlations are all 1.00 for FGV, BV and VBD. Variations in filter thickness have almost no effect on FGV, BV and VBD. When filter thickness was varied by +10%, there was no change in the mean ± SD VBD of the subjects, but the median shifted to 9.0%. When filter thickness was varied by −10%, there were no changes in both the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects.

Figure 3.

Comparisons between original and filter thickness modified images for (a) fibroglandular volume (FGV), (b) breast volume (BV) and (c) volumetric breast density (VBD) across the three manufacturer mammography systems (N = 915).

For mAs, detector gain and detector offset, the scatter plots showing the relationships for (a) FGV, (b) BV and (c) VBD between the original images and images processed with Volpara after each of these parameters was modified are very similar to those illustrated in Figure 3 (and hence not shown here). By varying mAs, detector gain or detector offset by ±10% from their original values, we observed correlations for FGV, BV and VBD between the original images and images processed with Volpara after each parameter modification are all 1.00. Our data indicates that variations in mAs, detector gain and detector offset have almost no effect on FGV, BV and VBD. When mAs and detector gain were varied by ±10%, there were no changes in the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects. When detector offset was varied by +10%, the mean ± SD and median VBD of the subjects shifted to 10.6 ± 5.9% and 9.0%, respectively. When detector offset was varied by −10%, the mean ± SD of VBD shifted to 10.4 ± 5.8%, but there was no change in the median.

For Gaussian noise-added images, the relationships between the original and noise-added images for FGV, BV and VBD were also investigated. The scatter plots showing the relationships between the original images and noise-added images for (a) FGV, (b) BV and (c) VBD when µ = 0 and σ = 1 are very similar to those illustrated in Figure 3 (and hence not shown here). Correlations are all 1.00 for FGV, BV and VBD, respectively, in this case. The mean ± SD and median VBD for the study population shifted to 10.6 ± 5.8% and 9.0%, respectively. We observed that as long as the image quality of the noise-added images remained within reasonable diagnostic quality, introducing Gaussian noise into the images has limited effects on FGV, BV and VBD, with the effect on VBD being more prominent in less dense breasts.

Overall, there were very strong positive and highly significant (p < 0.0001) relationships for FGV, BV and VBD between the original images and images processed with Volpara after each parameter was varied. The maximum shifts in the mean (1.2%) and median (1.1%) VBD of the study population occurred when CBT was varied by −10%. The results for the mean ± SD, median, IQR and Wilcoxon signed-rank test are summarized in Table 3. Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that there were significant differences in VBD resulting from CBT, kVp, detector offset and image noise variations when compared with VBD obtained from the original images. Variations in mAs, detector gain and filter thickness did not cause any significant changes in the VBD results.

Table 3.

Summary of mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR) and p-value from Wilcoxon signed-rank test for comparison between volumetric breast density (VBD) from the original images and VBD from images after each parameter variation

| Parameter variation | VBD (%) (N = 915) |

p-value from Wilcoxon test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 95% CI for mean | Median | 95% CI for median | IQR | ||

| No variation (original) | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | – |

| CBT +10% | 9.7 ± 5.4 | 9.4–10.1 | 8.3 | 8.0–8.6 | 6.8 | <0.0001 |

| CBT −10% | 11.7 ± 6.5 | 11.3–12.1 | 10.0 | 9.5–10.3 | 8.0 | <0.0001 |

| kVp +10% | 11.0 ± 6.0 | 10.6–11.3 | 9.4 | 9.0–9.7 | 7.4 | <0.0001 |

| kVp −10% | 9.7 ± 5.4 | 9.4–10.1 | 8.3 | 8.0–8.7 | 6.7 | <0.0001 |

| Filter thickness +10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 9.0 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.3 | 0.07 |

| Filter thickness −10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.1 | 0.15 |

| mAs +10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | 1.00 |

| mAs −10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | 1.00 |

| Detector gain +10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | 0.94 |

| Detector gain −10% | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 8.9 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | 1.00 |

| Detector offset +10% | 10.6 ± 5.9 | 10.2–10.9 | 9.0 | 8.7–9.4 | 7.3 | <0.0001 |

| Detector offset −10% | 10.4 ± 5.8 | 10.0–10.7 | 8.9 | 8.5–9.2 | 7.1 | <0.0001 |

| Gaussian noise added | 10.6 ± 5.8 | 10.1–10.8 | 9.0 | 8.6–9.2 | 7.2 | <0.0001 |

CBT, compressed breast thickness; CI, confidence interval; kVp, tube voltage; mAs, tube current–exposure time product; N, total number of subject.

Finally, Table 4 shows the linearly weighted kappa for the agreement between the VDG results obtained from the original images and those obtained from the images with each parameter variation. Tables 5–17 show the confusion matrices for VDG results from images processed with Volpara after each parameter was varied vs those from the original images. Weighted kappa for images with CBT varied by +10% and −10% vs the original images are 0.87 and 0.80, respectively. Weighted kappa for images with kVp varied by +10% and −10% vs the original images are 0.90 and 0.88, respectively. For filter thickness varied by ±10% vs the original images, weighted kappa is 0.99 for both. For images with mAs varied by ±10% vs the original images, weighted kappa is 1.00 for both. Weighted kappa for images processed with Volpara after detector gain was varied by ±10% vs the original images is 1.00 for both. Weighted kappa for images processed with Volpara after detector offset was varied by ±10% vs the original images is 0.98 for both. For Gaussian noise-added images (for µ = 0 and σ = 1) vs the original images, weighted kappa was 0.96. Overall, the linearly weighted kappa statistic shows substantial or almost perfect agreements between VDG results obtained from the original images and those obtained from the images processed after each parameter modification.

Table 4.

Linearly weighted kappa for the agreement between the Volpara density grade results obtained from the original images and those from the images after each parameter variation

| Parameter variation | Weighted kappa (N = 915) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| CBT +10% | 0.87 | 0.85–0.90 |

| CBT −10% | 0.80 | 0.77–0.83 |

| kVp +10% | 0.90 | 0.88–0.92 |

| kVp −10% | 0.88 | 0.86–0.90 |

| Filter thickness +10% | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Filter thickness −10% | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 |

| mAs +10% | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| mAs −10% | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Detector gain +10% | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Detector gain −10% | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Detector offset +10% | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 |

| Detector offset −10% | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 |

| Gaussian noise added | 0.96 | 0.95–0.98 |

CBT, compressed breast thickness; CI, confidence interval; kVp, tube voltage; mAs, tube current–exposure time product; N, total number of subject.

Table 5.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with compressed breast thickness (CBT) varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with CBT + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 99 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 127 (13.9%) |

| 2 | 4 | 220 | 39 | 0 | 263 (28.7%) |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 350 | 39 | 391 (42.7%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 132 | 134 (14.6%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.87, 95% confidence interval: 0.85–0.90.

Table 17.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with Gaussian noise added vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with Gaussian noise added | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88 (9.6%) |

| 2 | 15 | 238 | 1 | 0 | 254 (27.8%) |

| 3 | 0 | 12 | 388 | 2 | 402 (43.9%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 169 | 171 (18.7%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.96, 95% confidence interval: 0.95–0.98.

Table 6.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with compressed breast thickness (CBT) varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with CBT − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 56 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 58 (6.3%) |

| 2 | 46 | 177 | 4 | 0 | 227 (24.8%) |

| 3 | 1 | 69 | 342 | 1 | 413 (45.1%) |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 45 | 170 | 217 (23.7%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.80, 95% confidence interval: 0.77–0.83.

Table 7.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with tube voltage (kVp) varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with kVp + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 69 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 70 (7.7%) |

| 2 | 34 | 215 | 1 | 0 | 250 (27.3%) |

| 3 | 0 | 34 | 370 | 0 | 404 (44.2%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 171 | 191 (20.9%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.90, 95% confidence interval: 0.88–0.92.

Table 8.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with tube voltage (kVp) varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with kVp − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 130 (14.2%) |

| 2 | 1 | 221 | 38 | 0 | 260 (28.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 353 | 42 | 396 (43.3%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 129 | 129 (14.1%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.88, 95% confidence interval: 0.86–0.90.

Table 9.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with filter thickness varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with filter thickness + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 2 | 0 | 251 (27.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 387 | 0 | 388 (42.4%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 171 | 173 (18.9%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.99, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 10.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with filter thickness varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with filter thickness − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 2 | 0 | 251 (27.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 389 | 0 | 390 (42.6%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 171 | 171 (18.7%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.99, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 11.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with tube current–exposure time product (mAs) varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with mAs + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 1 | 0 | 250 (27.3%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 390 | 0 | 391 (42.7%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 171 | 171 (18.7%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 1.00, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 12.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images with tube current–exposure time product (mAs) varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with mAs − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 1 | 0 | 250 (27.3%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 390 | 0 | 391 (42.7%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 171 | 171 (18.7%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 1.00, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 13.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images processed with Volpara after detector gain was varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with detector gain + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 1 | 0 | 250 (27.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 390 | 0 | 391 (42.4%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 171 | 171 (18.9%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 1.00, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 14.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images processed with Volpara after detector gain was varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with detector gain − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 103 (11.3%) |

| 2 | 1 | 248 | 1 | 0 | 250 (27.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 390 | 0 | 391 (42.4%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 171 | 171 (18.9%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 1.00, 95% confidence interval: 0.99–1.00.

Table 15.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images processed with Volpara after detector offset was varied by +10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with detector offset + 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 97 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 98 (10.7%) |

| 2 | 6 | 244 | 1 | 0 | 251 (27.4%) |

| 3 | 0 | 5 | 385 | 0 | 390 (42.6%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 171 | 176 (19.2%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.98, 95% confidence interval: 0.97–0.99.

Table 16.

Volpara density grade (VDG) from images processed with Volpara after detector offset was varied by −10% vs VDG from the original images

| VDG from images with detector offset − 10% | VDG from original images |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 102 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 104 (11.4%) |

| 2 | 1 | 247 | 7 | 0 | 255 (27.9%) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 384 | 3 | 388 (42.4%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 168 | 168 (18.4%) |

| 103 (11.3%) | 250 (27.3%) | 391 (42.7%) | 171 (18.7%) | 915 | |

Weighted kappa = 0.98, 95% confidence interval: 0.97–0.99.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Commercially available VBD measurement systems are increasingly being used clinically for assessing breast density and its association with breast cancer risk. Nevertheless, these systems are known to be sensitive to errors in the recorded imaging physics parameters. In this study, we analysed the sensitivity and robustness of Volpara, to errors in various parameters including CBT, kVp, filter thickness, mAs, detector gain, detector offset and image noise. Volumetric measures including FGV, BV and VBD estimated by Volpara after the simulation of error in each parameter showed very high and significant correlations with the corresponding “ground truth” values. VDG results from images processed after parameter modifications also indicate substantial or almost perfect agreements with the corresponding “ground truth” results.

Our results based on large image set collected from three different manufacturer mammography systems supported the findings of Highnam et al,18 where it was found that variations in mAs and detector gain have negligible effects on FGV, BV and VDG. We also found that image noise has limited effect on VBD which is consistent with the study by Highnam et al18 based on a small number of images. For image noise, disagreements in VDG mostly occurred in the breasts with VDG 1 and 2 (Table 17), i.e. in the less dense breasts.

Our results indicated that CBT is the key parameter leading to the largest errors in the estimated VBD. Overall, our data show maximum shifts in the mean (1.2%) and median (1.1%) VBD of the study population occurred when CBT was varied by −10%. Furthermore, we also observed that errors in CBT have limited effect on FGV but the opposite effects on BV when compared with VBD. As CBT increases, BV increases, with the effect being more prominent in larger breasts, but VBD decreases with the effect being more prominent in denser breasts, and vice versa for the case as CBT decreases. This is because a larger breast will generally have a larger projected breast area on a mammogram, and also, BV is derived from multiplying the breast area by CBT, therefore there is a higher increase in BV for a larger breast as CBT increases. In addition, because the variations in CBT have limited impact on FGV, and also, VBD is the ratio of FGV over BV, when CBT increases and resulted in an increase in BV, there will be a greater decrease in VBD for a denser breast.

Besides, we also found that errors in kVp have limited effect on BV, but as it increases, both FGV and VBD also increase with the effects being more prominent in larger and denser breasts, and vice versa for the case as kVp decreases. As kVp increases, FGV also increases but BV is not affected and hence, the ratio of FGV over BV, i.e. VBD also increases. This also corresponds to the fact that larger and denser breasts usually require higher X-ray beam energy, i.e. higher kVp than smaller and less dense breasts for the same anode/filter combination. In addition, our data also show that errors in filter thickness and detector offset have limited effects in volumetric measures and VDG results.

In summary, our results indicate that errors in some of the imaging physics parameters such as mAs, filter thickness, detector gain, detector offset and image noise have limited impact on VBD estimation, whereas errors in other parameters such as CBT and kVp have greater impact on VBD estimation, with CBT being the key parameter leading to the largest errors in VBD.

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, we only investigated the errors in the major parameters such as the CBT, kVp, filter thickness, mAs, detector gain, detector offset and image noise on the volumetric measures. There are also errors in other parameters which might have impacts on the volumetric measures such as the target and filter materials. However, errors in the target and filter materials could only possibly occur if the manufacturers made mistakes in setting the default values, and these are very unlikely to happen. Hence, errors in the target and filter materials were not considered in this study.

Secondly, we varied the investigated parameters up to ±10% (expected clinical variations) from their original values recorded in the DICOM tags, but there is still small possibility for some mammography systems (such as the poorly calibrated ones) to have errors greater than what we had simulated. Nevertheless, this rarely occurs in mammography systems used in a clinical setup as such systems will generally be under certain quality assurance (QA) programs which will keep errors in the imaging parameters within acceptable limits. For example, the US Mammography Quality Standards Act and Program requires that both CBT and kVp errors to be within ±5 mm and ±5% from the selected or indicated values, respectively.32 Hence, routine QA tests help to minimize errors in volumetric density measures.

In addition, we should note that the automatic exposure control system, or the equivalent, on a mammography system will normally optimize the imaging parameters to produce consistent high-quality images. Hence, in reality, variations in CBT, for instance, might lead to a combined effect consisting of variations in all the kVp, mAs, anode/filter combination and other parameters. Although the combined effect could change the image pixel values and possibly lead to an error in the VBD estimation, we expect this error to be minimal in clinical setup since these automatic exposure control systems (under certain QA programs) would be properly calibrated to ensure that the images produced are of consistent image density across the clinical range of the parameters.

In conclusion, the Volpara software is robust and suitable for routine clinical use in quantifying breast density even if there are minor errors in some of the imaging physics parameters. It remains to be seen if the Volpara software is robust enough to track breast density changes over time where more stringent quality control might be necessary, but the results so far look promising.45,46

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All the authors do not have any financial interests in all the companies mentioned in this paper. The authors gratefully express their thanks to Dr Ralph Highnam, Dr Ariane Chan and Mr Ben MacDonell from Matakina Technology Ltd, New Zealand, for providing the Volpara software and technical advice in this study. The authors also thank the radiologists and radiographers at the University of Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia, for their professional support in this study.

Appendix A

The Python scripts used to vary the imaging physics parameters including compressed breast thickness (CBT), tube voltage (kVp), filter thickness, tube current-exposure time product (mAs) recorded in the DICOM tags, as well as add Gaussian noise to the digital mammograms are as follows:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import dicom

import dicom.encaps

import numpy as np

from dicom.dataset import Dataset, FileDataset

from dicom.sequence import Sequence

import dicom.UID

from dicom.datadict import DicomDictionary, NameDict, CleanName

from dicom.dataset import Dataset

import os

from pprint import pformat

import argparse

import sys

import copy

import fnmatch

import re

import shutil

import itertools

import cv2

def find_files(directory):

file_list = list()

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(unicode(directory)):

for basename in files:

if fnmatch.fnmatch(basename, “*.dcm”):

filename = os.path.join(root, basename)

file_list.append(filename)

return file_list

def parse_args():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description = “Duplicates a directory and modifies values”)

parser.add_argument(“--input”,“-i”, dest = 'input',type=str, required=True, help = “Input directory”)

parser.add_argument(“--output”,“-o”, dest = 'output',type=str, required=True, help = “Output directory”)

return parser.parse_args()

def main():

args = parse_args()

# Increase breast thickness by 10%

print “Creating breast thickness +10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “breast thickness +10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

breast_thickness = image.BodyPartThickness

except:

print “Could not access BodyPartThickness of ” + f

continue

image.BodyPartThickness = int(breast_thickness * 1.1)

image.save_as(f)

# Decrease breast thickness by 10%

print “Creating breast thickness -10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “breast thickness -10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

breast_thickness = image.BodyPartThickness

except:

print “Could not access BodyPartThickness of ” + f

continue

image.BodyPartThickness = int(breast_thickness * 0.9)

image.save_as(f)

# Increase KVP by 10%

print “Creating KVP +10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “KVP +10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

img_KVP = image.KVP

except:

print “Could not access KVP of ” + f

continue

image.KVP = img_KVP * 1.1

image.save_as(f)

# Decrease KVP by 10%

print “Creating KVP -10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “KVP -10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

img_KVP = image.KVP

except:

print “Could not access KVP of ” + f

continue

image.KVP = img_KVP * 0.9

image.save_as(f)

# Increase filter thickness by 10%

print “Creating filter thickness +10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “filter thickness +10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

filter_thickness_minimum = image.FilterThicknessMinimum

filter_thickness_maximum = image.FilterThicknessMaximum

except:

print “Could not access FilterThickness of ” + f

continue

image.FilterThicknessMinimum = filter_thickness_minimum * 1.1

image.FilterThicknessMaximum = filter_thickness_maximum * 1.1

image.save_as(f)

# Decrease filter thickness by 10%

print “Creating filter thickness -10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “filter thickness -10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

filter_thickness_minimum = image.FilterThicknessMinimum

filter_thickness_maximum = image.FilterThicknessMaximum

except:

print “Could not access FilterThickness of ” + f

continue

image.FilterThicknessMinimum = filter_thickness_minimum * 0.9

image.FilterThicknessMaximum = filter_thickness_maximum * 0.9

image.save_as(f)

# Increase mAs by 10%

print “Creating mAs +10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “exposure mAs +10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

exposure_mAs = image.Exposure

except:

print “Could not access Exposure of ” + f

continue

image.Exposure = int(exposure_mAs * 1.1)

image.save_as(f)

# Decrease mAs by 10%

print “Creating mAs -10% data set”

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “exposure mAs -10 percent”)

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

try:

exposure_mAs = image.Exposure

except:

print “Could not access Exposure of ” + f

continue

image.Exposure = int(exposure_mAs * 0.9)

image.save_as(f)

# Add Gaussian noise

print “Creating Gaussian noise data sets”

for i in (0, 1):

new_directory = os.path.join(args.output, “Gaussian_”+str(i))

try:

shutil.copytree(args.input, new_directory)

except:

print “Could not copy images to new directory”

files = find_files(new_directory)

for f in files:

try:

image = dicom.read_file(f)

except:

continue

pixel_data = image.pixel_array

random_data = np.random.normal(i, 1, pixel_data.shape)

pixel_data += random_data

image.PixelData = pixel_data.tostring()

image.save_as(f)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()

Contributor Information

Susie Lau, Email: slau007@hotmail.com.

Kwan Hoong Ng, Email: ngkh@ummc.edu.my.

Yang Faridah Abdul Aziz, Email: yangf@ummc.edu.my.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the High Impact Research Chancellory Grant UM.C/HIR/MOHE/06 from the Ministry of Education, Malaysia, and the Postgraduate Research Grant PG035-2013A from the University of Malaya, Malaysia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey JA, Bovbjerg VE. Quantitative assessment of mammographic breast density: relationship with breast cancer risk. Radiology 2004; 230: 29–41. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301020870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Yaffe MJ, Minkin S. Mammographic density: a hormonally responsive risk factor for breast cancer. J Br Menopause Soc 2006; 12: 186–93. doi: 10.1258/136218006779160436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 1178–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vachon CM, Brandt KR, Ghosh K, Scott CG, Maloney SD, Carston MJ, et al. Mammographic breast density as a general marker of breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16: 43–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsburg OM, Martin LJ, Boyd NF. Mammographic density, lobular involution, and risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2008; 99: 1369–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Barclay J, Sickles EA, Ernster V. Effect of age, breast density, and family history on the sensitivity of first screening mammography. JAMA 1996; 276: 33–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540010035027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg RD, Hunt WC, Williamson MR, Gilliland FD, Wiest PW, Kelsey CA, et al. Effects of age, breast density, ethnicity, and estrogen replacement therapy on screening mammographic sensitivity and cancer stage at diagnosis: review of 183,134 screening mammograms in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Radiology 1998; 209: 511–18. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.2.9807581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, White D, Finder CA, Taplin SH, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 1081–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology 2002; 225: 165–75. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Highnam R, Brady JM. Mammographic image analysis. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blot L, Zwiggelaar R. A volumetric approach to glandularity estimation in mammography: a feasibility study. Phys Med Biol 2005; 50: 695–708. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/4/009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwiggelaar R, Denton ER. Optimal segmentation of mammographic images. In: Pisano ED, ed. Proceedings of the 7th international workshop on digital mammography; 2004 June 18–24. Chapel Hill, NC: Springer; 2004. pp. 751–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding J, Warren R, Warsi I, Day N, Thompson D, Brady M, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of using standard mammogram form to predict breast cancer risk: case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17: 1074–81. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pawluczyk O, Augustine BJ, Yaffe MJ, Rico D, Yang J, Mawdsley GE, et al. A volumetric method for estimation of breast density on digitized screen-film mammograms. Med Phys 2003; 30: 352–64. doi: 10.1118/1.1539038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lokate M, Kallenberg MG, Karssemeijer N, Van den Bosch MA, Peeters PH, Van Gils CH. Volumetric breast density from full-field digital mammograms and its association with breast cancer risk factors: a comparison with a threshold method. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 3096–105. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malkov S, Wang J, Kerlikowske K, Cummings SR, Shepherd JA. Single X-ray absorptiometry method for the quantitative mammographic measure of fibroglandular tissue volume. Med Phys 2009; 36: 5525–36. doi: 10.1118/1.3253972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Highnam R. Model-based enhancement of mammographic images. PhD thesis. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 1992. [Cited 6 March 2016]. Available from: http://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/files/3431/PRG105.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Highnam R, Brady S, Yaffe M, Karssemeijer N, Harvey J. Robust breast composition measurement—Volpara™. In: Martí J, Oliver A, Freixenet J, Martí R, eds. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2010. pp. 342–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diffey J, Hufton A, Astley S. A new step-wedge for the volumetric measurement of mammographic density. In: Astley SM, Brady M, Rose C, Zwiggelaar R, eds. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2006. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malkov S, Wang J, Shepherd J. Improvements to single energy absorptiometry method for digital mammography to quantify breast tissue density. In: Krupinski E, ed. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel HG, Astley SM, Hufton AP, Harvie M, Hagan K, Marchant TE, et al. Automated breast tissue measurement of women at increased risk of breast cancer. In: Astley SM, Brady M, Rose C, Zwiggelaar R, eds. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2006. pp. 131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shepherd JA, Herve L, Landau J, Fan B, Kerlikowske K, Cummings SR. Novel use of single X-ray absorptiometry for measuring breast density. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2005; 4: 173–82. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufhold J, Thomas JA, Eberhard JW, Galbo CE, Trotter DE. A calibration approach to glandular tissue composition estimation in digital mammography. Med Phys 2002; 29: 1867–80. doi: 10.1118/1.1493215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Engeland S, Snoeren PR, Huisman H, Boetes C, Karssemeijer N. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2006; 25: 273–82. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.862741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tromans C, Brady S. The standard attenuation rate for quantitative mammography. In: Martí J, Oliver A, Freixenet J, Martí R, eds. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2010. pp. 561–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding H, Molloi S. Quantification of breast density with spectral mammography based on a scanned multi-slit photon-counting detector: a feasibility study. Phys Med Biol 2012; 57: 4719–38. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/15/4719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molloi S, Ducote JL, Ding H, Feig SA. Postmortem validation of breast density using dual-energy mammography. Med Phys 2014; 41: 081917. doi: 10.1118/1.4890295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diffey J, Hufton A, Beeston C, Smith J, Marchant T, Astley S. Quantifying breast thickness for density measurement. In: Krupinski E, ed. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 651–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonzo-Proulx O, Tyson A, Mawdsley G, Yaffe M. Effect of tissue thickness variation in volumetric breast density estimation. In: Krupinski E, ed. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 659–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branderhorst W, de Groot JE, Highnam R, Chan A, Bohm-Velez M, Broeders MJ, et al. Mammographic compression—a need for mechanical standardization. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulos A, McLean D, Rickard M, Heard R. Breast compression in mammography: how much is enough? Australas Radiol 2003; 47: 121–6. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8461.2003.01139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Mammography quality standards act and program 1992. [updated 11 March 2016; cited 16 March 2016]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Radiation-EmittingProducts/MammographyQualityStandardsActandProgram/default.htm

- 33.Couwenberg AM, Verkooijen HM, Li J, Pijnappel RM, Charaghvandi KR, Hartman M, et al. Assessment of a fully automated, high-throughput mammographic density measurement tool for use with processed digital mammograms. Cancer Causes Control 2014; 25: 1037–43. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0404-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Szekely L, Eriksson L, Heddson B, Sundbom A, Czene K, et al. High-throughput mammographic-density measurement: a tool for risk prediction of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2012; 14: R114. doi: 10.1186/bcr3238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brand JS, Czene K, Shepherd JA, Leifland K, Heddson B, Sundbom A, et al. Automated measurement of volumetric mammographic density: a tool for widespread breast cancer risk assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23: 1764–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brand JS, Humphreys K, Thompson DJ, Li J, Eriksson M, Hall P, et al. Volumetric mammographic density: heritability and association with breast cancer susceptibility loci. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: dju334. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eng A, Gallant Z, Shepherd J, McCormack V, Li J, Dowsett M, et al. Digital mammographic density and breast cancer risk: a case-control study of six alternative density assessment methods. Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16: 439. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0439-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartman K, Highnam R, Warren R, Jackson V. Volumetric assessment of breast tissue composition from FFDM images. In: Krupinski E, ed. Digital mammography. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gubern-Merida A, Kallenberg M, Platel B, Mann RM, Marti R, Karssemeijer N. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms: a validation study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e85952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tagliafico A, Tagliafico G, Astengo D, Airaldi S, Calabrese M, Houssami N. Comparative estimation of percentage breast tissue density for digital mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, and magnetic resonance imaging. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 138: 311–17. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2419-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Aziz A, Newitt D, Joe B, Hylton N, Shepherd J. Comparison of Hologic’s Quantra volumetric assessment to MRI breast density. In: Maidment AA, Bakic P, Gavenonis S, eds. Breast imaging. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2012. pp. 619–26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Azziz A, Fan B, Malkov S, Klifa C, Newitt D, et al. Agreement of mammographic measures of volumetric breast density to MRI. PLoS One 2013; 8: e81653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ACR. Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS®) atlas. 5th edn. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44. SciPy.org [homepage on the Internet]. The SciPy Community; c2008–09 [updated 18 October 2015; cited 6 March 2016]. Available from: http://docs.scipy.org/doc/numpy-1.10.1/reference/generated/numpy.random.normal.html.

- 45.Wang K, Chan A, Highnam R. Robustness of automated volumetric breast density estimation for assessing temporal changes in breast density. 2015 March 4–8; Vienna, Austria. European Society of Radiology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kallenberg M, Karssemeijer N. Temporal stability of fully automatic volumetric breast density estimation in a large screening population. 2013 March 4–8; Vienna, Austria. European Society of Radiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]