Abstract

Objective:

Cone beam CT (CBCT) images contain more scatter than a conventional CT image and therefore provide inaccurate Hounsfield units (HUs). Consequently, CBCT images cannot be used directly for radiotherapy dose calculation. The aim of this study is to enable dose calculations to be performed with the use of CBCT images taken during radiotherapy and evaluate the necessity of replanning.

Methods:

A patient with prostate cancer with bilateral metallic prosthetic hip replacements was imaged using both CT and CBCT. The multilevel threshold (MLT) algorithm was used to categorize pixel values in the CBCT images into segments of homogeneous HU. The variation in HU with position in the CBCT images was taken into consideration. This segmentation method relies on the operator dividing the CBCT data into a set of volumes where the variation in the relationship between pixel values and HUs is small. An automated MLT algorithm was developed to reduce the operator time associated with the process. An intensity-modulated radiation therapy plan was generated from CT images of the patient. The plan was then copied to the segmented CBCT (sCBCT) data sets with identical settings, and the doses were recalculated and compared.

Results:

Gamma evaluation showed that the percentage of points in the rectum with γ < 1 (3%/3 mm) were 98.7% and 97.7% in the sCBCT using MLT and the automated MLT algorithms, respectively. Compared with the planning CT (pCT) plan, the MLT algorithm showed −0.46% dose difference with 8 h operator time while the automated MLT algorithm showed −1.3%, which are both considered to be clinically acceptable, when using collapsed cone algorithm.

Conclusion:

The segmentation of CBCT images using the method in this study can be used for dose calculation. For a patient with prostate cancer with bilateral hip prostheses and the associated issues with CT imaging, the MLT algorithms achieved a sufficient dose calculation accuracy that is clinically acceptable. The automated MLT algorithm reduced the operator time associated with implementing the MLT algorithm to achieve clinically acceptable accuracy. This saved time makes the automated MLT algorithm superior and easier to implement in the clinical setting.

Advances in knowledge:

The MLT algorithm has been extended to the complex example of a patient with bilateral hip prostheses, which with the introduction of automation is feasible for use in adaptive radiotherapy, as an alternative to obtaining a new pCT and reoutlining the structures.

INTRODUCTION

One of the desirable objectives during external beam radiotherapy of the prostate is the delivery of a uniform radiation dose to the treatment volume while sparing organs at risk. In practice, this may be difficult to achieve due to day-to-day changes in patient positioning, patient shape and internal organ movement during the treatment course.1 Interfractional motions such as variations in bladder and rectum volume have been demonstrated to have significant effects on prostate position and a negative impact on the accuracy of the treatment course.2

The implementation of image-guided radiation therapy in clinical practice, such as kilovoltage cone beam CT (kV-CBCT), has improved tumour targeting and tumour control during the treatment delivery process and reducing dose delivery to normal tissues. Cone beam CT (CBCT) has been used to correct patient setup in the treatment position and to monitor any anatomical deformations in three dimensions with sufficient soft-tissue contrast.3 In addition, CBCT can be feasible for adaptive radiotherapy (ART), e.g. dose recalculation, if the Hounsfield units (HUs) are accurate and reliable.4

Owing to its cone beam geometry, the amount of scatter in CBCT images is greater than that of conventional CT images (fan beam) and is dependent on the scanned object's size, collimator and filter used.5 The image quality also depends on acquisition parameters, i.e. tube current and potential and the number of projections. In addition, limited gantry rotation speed and large field of view (FOV) in a single rotation reduces image quality. Therefore, CBCT images provide inaccurate HUs and, consequently, cannot be used directly for dose calculation.6 Therefore, if there are significant anatomical changes observed on the CBCT images, acquiring another CT is necessary for an accurate assessment of dose differences. This procedure is time consuming across all staff groups involved in the radiotherapy pathway and additional dose is delivered to the patients. Thus, it would be sufficient to use CBCT images that were already taken during radiotherapy for evaluating the necessity of replanning. Many articles have studied the use of CBCT data for dose recalculation, which is still an active area for research.6

To deal with HU calibration of CBCT images, Richter et al7 proposed a method where HU–electron density conversion curves were based on average CBCT HU values for separate treatment sites in order to generate population-specific conversion curves. Such an approach is still subject to CBCT artefacts and can result in dose calculation errors of >5% when compared with planning CT (pCT)-based dose calculation.6 Some studies deal with correcting scatter by applying quite unsophisticated software corrections to CBCT images before reconstruction.8 Such a method may be unable to accurately reconstruct higher density material for a large scanned object size. In addition, it may be difficult to implement such a method in a clinic even though recent commercial software releases provide sophisticated scatter correction algorithms.9

Other studies deal with adjustment techniques to correct CBCT HU values, such as mapping the HUs in CT images to the equivalent points in the CBCT image geometry after rigid or deformable image registration (DIR).10,11 In addition, image cumulative histograms can be used to adjust HU values between pCT and CBCT images.6 Another technique uses a multilevel threshold (MLT) algorithm as proposed by Boggula et al, where the pixel values of CBCT images were replaced with a small number of fixed HU values as in CT for air, soft-tissue and bone.12–14 Onozato et al14 excluded water and used fat and muscle instead, resulting in a dosimetric difference <2%. In addition, Fotina et al6 used the same technique, calling it a density override technique, but with a range of HU values for bone (soft bony structures, hard bone and teeth) and air/low density regions (rectal balloon and lung). All other regions are assumed to be water equivalent assigned with one HU value, resulting in a dosimetric difference <2%.

Recently, Dunlop et al9 assessed the CBCT dose calculation accuracy for density override approaches for four pelvis cases, where CBCT voxels were assigned as water only and then as either water or bone (water only and water-and-bone methods). This was then compared with a scatter correction and automated density override approach that is available in the RayStation TPS v. 3.99 (RaySearch Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden). In the automated density override approach, six different densities (air, lung, adipose tissue, connective tissue, cartilage/bone and higher density for prosthesis) are assigned to the CBCT image by binning the CBCT image histogram into six density levels. Compared with pCT acquired on the same day as the CBCT, the results showed that the automated approach was superior to the other methods, when considering smaller patients (with anteroposterior distance <25 cm). For larger patients, the water-only method gave the best accuracy.

The occurrence of inhomogeneities in the patient anatomy, e.g. hip replacements, has the ability to complicate the automated process, requiring the addition of additional set densities. In fact, none of the above studies used a patient with prostheses, which would provide a more general assessment of dose calculation using CBCT. Almatani et al15 studied CBCT-based dose calculations of a patient with prostate cancer with a single hip prosthesis using the MLT algorithm. The work showed that it was necessary to extend the MLT algorithm to categorize pixel values into segments on a region-by-region basis, with the region size changing depending on the anatomical features. In addition, a larger number of materials (up to 8) than typically used in previous works were explored. The results showed that five values of HU (air, adipose, water, cartilage/bone and metal implant) gave the best balance between dose accuracy (−1.9%) and operator time (5 h). However, the length of operator time needed could make it difficult to implement this as a technique in the clinic.

The aim of this work is to develop a more robust method to account for the full range of patient size as well as the difficulties presented by the metal artefacts in both pCT and CBCT images. A CBCT-based dose calculation of a patient with bilateral metal hip prostheses is presented using the extended MLT algorithm in the same manner, extending upon those proposed previously by the authors for a single hip prosthesis. In addition, an automated MLT algorithm was developed to reduce the operator time associated with the manual MLT algorithm. With the flexibility of a region-by-region approach, it is envisaged that the method can be applicable for the automation of dose calculation on segmented MR images and could be of interest to MR-based ART.9

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Cone beam CT image acquisition

The radiographic volumetric imaging integrated in an Elekta Synergy® linear accelerator (XVI™ v. 4.5; Elekta, Crawley, UK) was used to acquire CBCT images. The CBCT scans were acquired with a FOV (medium FOV) of 41 cm in diameter and 17.85 cm in the axial direction with a bowtie filter added (F1). CBCT images were reconstructed with 1-mm cubic voxels and averaged in the longitudinal direction for 3-mm slice thickness. The images were then transferred to the Oncentra® MasterPlan (OMP) treatment planning system v. 4.3 (Elekta, Best, Netherlands) via digital imaging and communications in medicine protocol for dose calculation.

Patient study

This study was performed on a patient with bilateral metal hip prostheses replacement treated at the Department of Clinical Oncology and Radiotherapy, South West Wales Cancer Centre ABM University Health Board, Swansea, Wales. The anteroposterior separation of the patient was 26.5 cm. Such a challenging case provides a good assessment of dose calculation using CBCT due to the difficulties presented by the metals artefacts in both pCT and CBCT images. The artefacts in pCT were reassigned as water in the original patient plan using a bulk density correction (Figure 1a). An intensity-modulated radiotherapy treatment with five 6-MV photon fields, at gantry angles of 35°, 145°, 180°, 235° and 300° was performed. The prescription dose was 70 Gy in 35 fractions. Dose distribution was calculated using pencil beam (PB) and collapsed cone (CC) algorithms to allow the comparison with Monte Carlo (MC) algorithm and to identify the effects of HU on dose calculation.

Figure 1.

A slice of the planning CT (a) and the original cone beam CT (CBCT) (b) and the resultant images after segmentation CBCT using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (c) and the automated MLT (d) showing the radius number from 1 to 5.

Modification of cone beam CT images

The MLT algorithm, used to correct CBCT data, involves categorizing pixel values in the CBCT images into segments of homogeneous HU using MATLAB® scripts (Mathworks, Natick, MA) to generate segmented CBCT (sCBCT) data. Based on Almatani et al,15 the binning of CBCT images of a patient with hip prosthesis into five HU values results in sufficiently accurate and clinically acceptable dose distribution. Considering more than five HU values provides more anatomical information and improves dose calculation accuracy (by 0.23%) but would require more operator time (58%), as the sensitivity increases when increasing the number of HU bins to define the material type. Therefore, in this study, five values of HU were used to segment CBCT images that represent air (−976 HU), adipose tissue (−96 HU), water (0 HU), 2/3 cartilage and 1/3 bone (528 HU), and metal implants (2976 HU). The ranges of pixel values in the CBCT images were: air (0–200), adipose tissue (201–700), water (701–875), 2/3 cartilage and 1/3 bone (876–1600), and metal implant (1601–8000).

The threshold values for each material at these intervals are dependent on the geometry since noise and scatter in CBCT is variable, especially in the presence of high-density materials, as shown in Figure 1b.16 In this study, the MLT algorithm was used in two ways, using a manual and an automated procedure. In the manual procedure, the CBCT images were divided into regions with sets of different threshold values, which are determined on a region-by-region basis, to sufficiently correct for the artefacts. The shape of each region is a rectangular cuboid. In general, the greater the variation in the scatter, the greater the number of regions that need to be considered, and the size of the region decreases as it gets closer to inhomogeneities. The resultant sCBCT images using this procedure are referred to as sCBCTman.

In the automated procedure, the CBCT images were divided into five concentric rings, which are uniform in shape through all slices, using MATLAB scripts, as shown in Figure 1d. The centre of the inner radius (radius 1) was defined at the centre of the patient geometry, which can be changed by the user. The lower threshold values for each material changes with the radius but is easily determined by the user's analysis of the central slice. For example, the lower threshold value for water, in the inner radius, was defined in relation to the pixel value with the maximum frequency in the slice according to the ratio of the lower threshold value of water and the pixel value with the maximum frequency in the central slice. The same procedure was applied for each material in each radius. The resultant sCBCT images using this procedure are referred to as sCBCTauto.

The use of a radial shape was motivated by the fact that, in CBCT, the issue of the scatter occurs spherically and ring atrefacts are caused by miscalibrated detector pixel lines/rows, elements or manufacturing defects at a fixed location in the flat panel detector (FPD). In addition, owing to the presence of the bilateral hip prostheses, the low energetic X-rays are absorbed, thus the polychromatic beam becomes gradually harder. Consequently, the FPD exhibits pixel-to-pixel sensitivity variations that lead to ring artefacts.17 In a pelvic region with prostheses, there is a rapid change in the exposure to the FPD from frame to frame, receiving high exposure then followed by low exposure due to the strong attenuation of the metal. This leads to so-called radar artefacts that appear as a circular radar bright-shaded region, owing to inconsistencies in detector signal and/or gain.18

Monte Carlo calculation

The Elekta Synergy linear accelerator was modelled using Electron Gamma Shower, which is one of the most popular MC codes for medical physics.19 BEAMnrc and DOSXYZnrc are two applications in Electron Gamma Shower code that are used to simulate the beam generated from the treatment head and to score dose deposition in voxel grids, respectively. In this study, 90 million particles were used for each beam to provide an accurate simulation with a low statistical uncertainty. High performance computing (HPC Wales20) was used to speed up MC calculations. The MC normalization was performed by calculating the dose in a water phantom under the standard reference conditions (10 × 10 field size, 100-cm2 source-to-surface distance and 5-cm2 depth).

Treatment planning evaluation and comparison

The sCBCT (both sCBCTman and sCBCTauto) and pCT images fusion was accomplished with manual rigid registration using ProSoma software v. 3.3 (MedCom, Darmstadt, Germany), and the structure sets were then transferred to the sCBCT images without any modification except the external contour. The plans were then copied to sCBCT using the same geometry and MU values, and doses were recalculated using the PB and CC algorithms. For MC calculation, the pCT artefacts, caused by the presence of the hip prostheses, were changed to a water material of uniform density using a MATLAB script. The MC dose calculation was then performed on pCT and sCBCT images using the same HU-electron density (ED) calibration as in OMP. The MC dose file (.3ddose) and the digital imaging and communications in medicine RT file were then imported into the computational environment for radiotherapy research software to compare the resultant dose distribution.21 Dose–volume histograms were compared between pCT and sCBCT plans. The maximum dose (Dmax), mean dose (Dmean) and minimum dose (Dmin) parameters for the planning target volume (PTV), the prostate and seminal vesicles, and the rectum and bladder were compared. The coverage of the PTV, the dose to 95% of the PTV (D95%) and the relative volume doses delivered to the rectum and bladder (V65 and V70) were compared. In addition, the volume of the right (RT)/left (LT) hip and bone were calculated in the pCT scan and compared with those in the sCBCTman and sCBCTauto scan to show how close the two scans were. To quantitatively appraise the differences between the pCT and sCBCT plans, especially for the PTV, rectum and bladder, a gamma index analysis was performed using the pCT plan as a reference. The criteria were set as 3-mm distance to agreement, 3% dose difference and 5% low dose threshold. The conformity index (CI) was calculated for all sCBCT plans and then compared with the pCT plans using PB, CC and MC algorithms.22 In addition, the dose at the isocentre (at the geometric centre of the prostate PTV) was compared between the pCT and sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

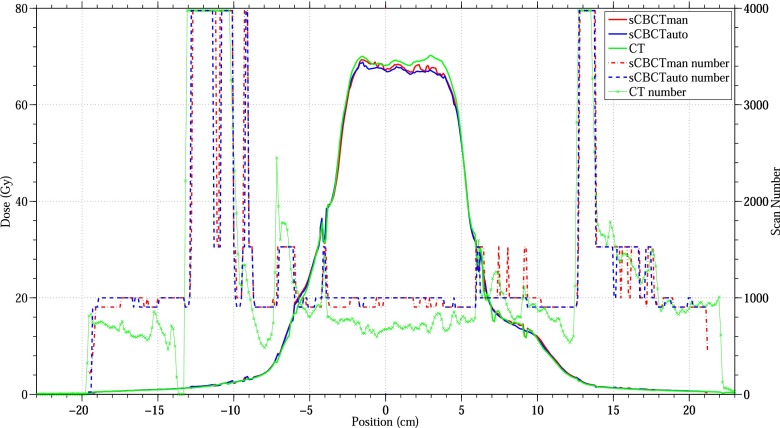

Figure 2 shows the cross-plane dose profile of pCT, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto at the depth of the plan isocentre and the CT number of the pCT, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto scans at that depth. In general, the sCBCTman and sCBCTauto profiles are in good agreement with the pCT profile especially at the implant/tissue interface. For bone regions, the sCBCTauto numbers showed less agreement with pCT numbers, compared with sCBCTman numbers where some of these regions were considered as water. In addition, the sCBCTauto overestimated some adipose tissue regions and considered it as water, especially in the PTV region (high-dose region), leading to an underestimation of the dose in that region by −4.4%. On the other hand, sCBCTman numbers considered more adipose tissue than sCBCTauto numbers, thus the dose difference with the pCT dose profile was less when compared with the sCBCTauto dose profile. The largest difference between the pCT and sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans was in the PTV region where pCT was 69.1 Gy, sCBCTman was 66.1 Gy and sCBCTauto was 65.8 Gy when using MC algorithm.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the dose profile of planning CT, segmentation CBCT using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto) plans at the isocentre depth using Monte Carlo algorithm. The second y axis represents the sCBCTman number, sCBCTauto number and CT number.

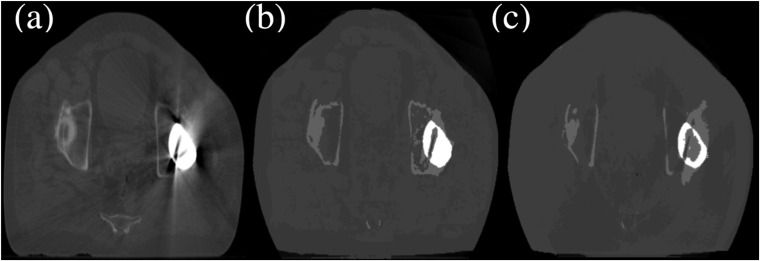

Figure 3 shows the differences in the right (RT)/left (LT) hip and bone volumes between the pCT scan, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto scans. Compared with the pCT scan, the largest difference between sCBCTman and sCBCTauto was found in the LT hip where it was overestimated by 6.8% in sCBCTman and underestimated by −30.2% in sCBCTauto. This underestimation was due to the fact that the automated MLT algorithm was unable to accurately correct cupping artefacts due to the increased amount of scatter and beam hardening inside the LT hip, resulting in dark streaks.17,18 Thus, the automated MLT algorithm erroneously replaced the artefacts with bone HU values, whereas the manual MLT correctly replaced the artefacts with metal HU values as shown in Figure 4. On the other hand, both MLT algorithms overestimated the RT hip where scatter and bright streak artefacts were erroneously replaced with hip HU values, leading to a significant reduction in the RT bone volume around that region. Another reason for the underestimation of both bone volumes in both MLT algorithms might be due to the fact that streak artefacts in pCT increased the number of high HU values and were not corrected (only for dose calculation), where in sCBCT, both MLT algorithms attempted to correct for this.

Figure 3.

Right hip (RThip)/left hip (LThip) and bone [right bone (RTbone)/left bone (LTbone)] volume differences between planning CT and segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman)/segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto).

Figure 4.

A slice of the planning CT (a) and the resultant images after segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto) (b and c, respectively), showing the Hounsfield unit value difference in the left hip prosthesis.

Figure 5 shows the dose–volume histogram of a prostate intensity-modulated radiotherapy plan with a prescription dose of 70 Gy in 35 fractions. It shows the dose of the pCT, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans to the PTV, rectum and bladder using the CC algorithm. Both sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans showed almost the same difference from the pCT plan, except for the PTV where sCBCTman showed better agreement, the difference in Dmax between the pCT and sCBCTman plans was −0.56% and between the pCT and sCBCTauto was −1.4%. Compared with the pCT plan, the sCBCTman plan underestimated Dmean and Dmin by −1% and −0.3%, respectively, whereas the sCBCTauto plan underestimated Dmean and Dmean by −1.6% and −1%, respectively. The MC and PB algorithm showed similar results to CC algorithm (Table A1 in Appendix A). Compared with pCT plan, the bladder V65 was reduced by 56% and 58% in sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans, respectively, when using CC algorithm, showing better bladder sparing (Table 1). There was a trade-off in the D95 of the PTV, which reduced by 9% and 14% in sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans, respectively, when using the CC algorithm. Significant organ deformation was observed between the pCT and CBCT scans, especially in the bladder volume (>15% reduction). This deformation resulted in large differences in Dmean for the bladder in both sCBCTman (−48.8%) and sCBCTauto (−49.2%).

Figure 5.

Dose–volume histogram comparison of planning CT (—), segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) (—·—) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto) (—·—) intensity-modulated radiotherapy plans for planning target volume (PTV), rectum and bladder using collapsed cone algorithm.

Table 1.

Planning target volume (PTV) coverage for the planning CT, segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto). The dose to 95% (D95) of PTV and minimum dose (Dmin) and the percentage of rectal and bladder volumes receiving 65 (V65) and 70 Gy (V70)

| Scan | PTV |

Rectum |

Bladder |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D95 | Dmin | V65 | V70 | V65 | V70 | ||

| CT | PB | 99.7 | 64.9 | 17.4 | 0.93 | 11.4 | 3.38 |

| CC | 95.76 | 61.9 | 14.36 | 0 | 10.57 | 0.35 | |

| MC | 80.42 | 55.9 | 13.78 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| sCBCTman | PB | 94.51 | 62.5 | 12.83 | 0 | 5.13 | 0.52 |

| CC | 86.99 | 61.7 | 10.74 | 0 | 4.6 | 0 | |

| MC | 80.13 | 55.9 | 10.36 | 0 | 4.2 | 0 | |

| sCBCTauto | PB | 92.99 | 62.1 | 12.25 | 0 | 4.96 | 0.3 |

| CC | 82.1 | 61.3 | 9.66 | 0 | 4.39 | 0 | |

| MC | 75.65 | 53.5 | 9.26 | 0 | 4.01 | 0 | |

CC, collapsed cone; MC, Monte Carlo algorithm; PB, pencil beam.

Previous studies used either deformable electron density or DIR to improve the dose calculation accuracy and to correct the uncertainty from organ deformation.11,14 For a standard patient with prostate cancer, the accuracy of dose calculation could be improved by 1–2% using these methods. Thor et al stated that the accuracy of DIR can be affected by bowel gas and artefacts from gold fiducial markers inside the prostate.23 Thus, in some cases, DIR would result in no improvement in the accuracy of the dose calculation.14 In this study, the image quality of both pCT and sCBCT images was affected by streak artefacts caused by the presence of the bilateral hip prostheses, thus the uncertainty associated with using DIR would be increased.

Dunlop et al9 eliminated the need for and uncertainties associated with the DIR by acquiring pCT on the same day as the CBCT scan, to be used as the ground truth for dose calculation. Thus, additional doses could be delivered to the patients.

Figure 6a shows the CI values of the pCT, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans using PB, CC and MC algorithms. In general, the differences in the CI values between pCT and sCBCTman were smaller than those between pCT and sCBCTauto using all algorithms. The difference of the CI values between pCT and sCBCTman were −26.7 %, −42.8% and −15.6% when using PB, CC and MC algorithms, respectively. On the other hand, the difference of the CI values between pCT and sCBCTauto were −38.9%, −74.1% and −46.9% when using PB, CC and MC algorithms, respectively. However, according to the RTOG guidelines, the CI values between 0.9 and 1 indicate that the target volume is not adequately covered by the prescribed isodose with a minor violation, whereas for CI values of <0.9, the treatment plan are rated major violations but may nevertheless be considered to be acceptable.24

Figure 6.

(a) Conformity index (CI) comparison between planning CT, segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto) plans using pencil beam (PB), collapsed cone (CC) and Monte Carlo (MC) algorithm. (b) Summary of the γ index with fixed distance to agreement = 3 mm and dose difference = 3% for the calculation points falling inside the planning target volume (PTV), rectum and bladder, showing the fraction of points resulting with γ < 1. γAI, γ agreement index.

Figure 6b shows the γ agreement index for the calculation points falling inside the PTV, rectum and bladder for the pCT, sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans, showing the fraction of points resulting in γ < 1. For the bladder region, all the calculation points passed the gamma test when using the PB and CC algorithms, whereas using the MC algorithm, 99.9% and 99.8% showed γ < 1 for sCBCTman and sCBCTauto, respectively. The lowest number of points that passed was found in the rectum region when using MC algorithm, where 98.7% showed γ < 1 in sCBCTman and 97.7% showed γ < 1 in sCBCTauto plans, which is clinically acceptable. Son et al25 stated that γ value is considered acceptable when the passing rate is >95% with 3-mm distance to agreement and 3% dose difference criteria.

Table 2 shows the dose difference between pCT and sCBCT plans at the isocentre using all algorithms. In general, both sCBCTman and sCBCTauto plans showed differences of less than −2% compared with the pCT plan using all algorithms, which are both considered to be clinically acceptable. It can be seen that the difference between the sCBCTman and sCBCTauto is larger when using CC and MC algorithms than that when using the PB algorithm. This is due to the fact that the PB algorithm in OMP calculates dose to water, whereas the CC algorithm calculates dose to medium, as does the MC algorithm.26 Therefore, the PB algorithm would be less sensitive than CC and MC for calculating the dose using different scans. Thus, MC and CC algorithms minimized uncertainty related to the dose calculation as well as identifying those introduced by different scans. However, for the MC calculation, the difference increased from −0.4% in the sCBCTman plan to −1.4% in sCBCTauto plan when compared with the pCT plan. On the other hand, the operator time required for defining the threshold values for different regions in sCBCTman was 8 h, whereas in sCBCTauto, the threshold values were defined automatically and takes 20 min of operator time. Some manual modification to ensure an appropriate assignment of each material in sCBCTauto scan was still needed to improve the accuracy, but it requires much less (approximately 95%) operator time than sCBCTman scan. Dividing CBCT images into five concentric rings was accurate enough to correct the variation in the pixel value with position in the CBCT images. As a result, the automated MLT algorithm reduced the operator time with an acceptable accuracy. This time saved could turn this technique from research based to a clinical implementation and makes it superior to the manual approach. Compared with the proposed technique in this article, acquiring a new pCT is more time consuming; increases work load on physicists, physicians and radiographers, which can take up to a day in a busy radiotherapy department; and more importantly, additional dose is delivered to the patient.

Table 2.

Dose comparison between planning CT, segmentation cone beam CT (CBCT) using the manual multilevel threshold (MLT) (sCBCTman) and segmentation CBCT using the automated MLT (sCBCTauto) plans at the isocentre using pencil beam (PB), collapsed cone (CC) and Monte Carlo (MC) algorithms

| Scan | sCBCTman |

sCBCTauto |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB | CC | MC | PB | CC | MC | |

| Dose difference (%) | −0.81 | −0.46 | −0.39 | −1.44 | −1.36 | −1.39 |

CONCLUSION

The segmentation of CBCT images using methods in this study can be used for dose calculation. For a patient with prostate cancer with bilateral hip prostheses, the MLT algorithms achieved a sufficient dose calculation accuracy that is clinically acceptable. The automated MLT algorithm reduced the operator time associated with the MLT algorithm, making it possible to implement the technique in the clinic. Thus, this method would be feasible for ART, as an alternative to obtaining a new pCT and reoutlining the structures. This method can be applicable for dose calculation on MR images and could be of interest to MR-based ART.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Dose and coverage differences between segmentation cone beam CT (sCBCT) plans and planning CT plan in percentage for the planning target volume (PTV), rectum and bladder using pencil beam (PB), collapsed cone (CC) and Monte Carlo (MC) algorithms

| Scan | sCBCTman |

sCBCTauto |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB | CC | MC | PB | CC | MC | ||

| PTV | Dmax | −0.83 | −0.56 | 3.42 | −1.38 | −1.40 | 0.00 |

| Dmean | −1.54 | −1.00 | −0.60 | −1.97 | −1.60 | −1.20 | |

| Dmin | −3.69 | −0.32 | 0.00 | −4.31 | −0.96 | −4.29 | |

| Rectum | Dmax | −1.98 | −2.28 | −2.26 | −1.98 | −2.56 | −2.54 |

| Dmean | −2.57 | −2.27 | −2.40 | −2.69 | −2.56 | −2.66 | |

| Dmin | 8.69 | 8.00 | 31.57 | 8.69 | 8.00 | 31.57 | |

| Bladder | Dmax | −1.11 | −1.13 | 0.57 | −1.66 | −1.13 | 0.85 |

| Dmean | −48.60 | −48.84 | −47.15 | −49.04 | −49.17 | −47.414 | |

| Dmin | −43.47 | −52.17 | −47.05 | −43.47 | −52.17 | −47.05 | |

Dmax, maximum dose; Dmean, mean dose; Dmin, minimum dose; sCBCTauto, sCBCT using the automated multilevel threshold; sCBCTman, sCBCT using the manual multilevel threshold.

Contributor Information

Turki Almatani, Email: turkialmatani@gmail.com.

Richard P Hugtenburg, Email: R.P.Hugtenburg@Swansea.ac.uk.

Ryan D Lewis, Email: Ryan.Lewis2@wales.nhs.uk.

Susan E Barley, Email: Susan.Barley@osl.uk.com.

Mark A Edwards, Email: Mark.Edwards2@wales.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Langen KM, Jones DT. Organ motion and its management. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 50: 265–78. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciernik IF, Baumert BG, Egli P, Glanzmann C, Ltolf UM. On-line correction of beam portals in the treatment of prostate cancer using an endorectal balloon device. Radiother Oncol 2002; 65: 39–45. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(02)00187-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffray DA, Siewerdsen JH, Wong JW, Martinez AA. Flat-panel cone-beam computed tomography for image-guided radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 53: 1337–49. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02884-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan K, Mohammadi M, Shepherd J. Cone beam computed tomography for adaptive radiotherapy treatment planning. J Med Biol Eng 2014; 34: 377–85. doi: 10.5405/jmbe.1372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stock M, Pasler M, Birkfellner W, Homolka P, Poetter R, Georg D. Image quality and stability of image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT) devices: a comparative study. Radiother Oncol 2009; 93: 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fotina I, Hopfgartner J, Stock M, Steininger T, Ltgendorf-Caucig C, Georg D. Feasibility of CBCT-based dose calculation: comparative analysis of HU adjustment techniques. Radiother Oncol 2012; 104: 249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter A, Hu Q, Steglich D, Baier K, Wilbert J, Guckenberger M, et al. Investigation of the usability of conebeam CT data sets for dose calculation. Radiat Oncol 2008; 3: 42. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poludniowski GG, Evans PM, Webb S. Cone beam computed tomography number errors and consequences for radiotherapy planning: an investigation of correction methods. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 84: e109–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunlop A, McQuaid D, Nill S, Murray J, Poludniowski G, Hansen VN, et al. Comparison of CT number calibration techniques for CBCT-based dose calculation. Strahlenther Onkol 2015; 191: 970–8. doi: 10.1007/s00066-015-0890-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Zijtveld M, Dirkx M, Heijmen B. Correction of conebeam CT values using a planning CT for derivation of the dose of the day. Radiother Oncol 2007; 85: 195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Schreibmann E, Li T, Wang C, Xing L. Evaluation of on-board kV cone beam CT (CBCT)-based dose calculation. Phys Med Biol 2007; 52: 685–705. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/3/011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boggula R, Wertz H, Lorenz F, Madyan YA, Boda-Heggemann J, Schneider F, et al. A proposed strategy to implement CBCT images for replanning and dose calculations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 69: S655–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boggula R, Lorenz F, Abo-Madyan Y, Lohr F, Wolff D, Boda-Heggemann J, et al. A new strategy for online adaptive prostate radiotherapy based on cone-beam CT. Z Med Phys 2009; 19: 264–76. doi: 10.1016/j.zemedi.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onozato Y, Kadoya N, Fujita Y, Arai K, Dobashi S, Takeda K, et al. Evaluation of onboard kV cone beam computed tomography-based dose calculation with deformable image registration using hounsfield unit modifications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 89: 416–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almatani T, Hugtenburg R, Lewis R, Barley S, Edwards M. Simplified material assignment for cone beam computed tomography-based dose calculations of prostate radiotherapy with hip prostheses. J Radiother Pract 2016; 15: 170–80. doi: 10.1017/S1460396915000564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pineda AR, Siewerdsen JH, Tward DJ, eds. Analysis of image noise in 3D cone-beam CT: Spatial and Fourier domain approaches under conditions of varying stationarity. Proceedings of SPIE. Vol. 6913; 2008. p. 69131Q.

- 17.Shaw CC. Cone beam computed tomography. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourland JD. Image-guided radiation therapy. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawrakow I, Rogers DW. The EGSNRC code system. NRC report PIRS-701. Ottawa, ON: NRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.HPC Wales. Bangor, UK. [Accessed 8 December 2015]. Available from: http://www.hpcwales.co.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deasy JO, Blanco AI, Clark VH. CERR: a computational environment for radiotherapy research. Med Phys 2003; 30: 979–85. doi: 10.1118/1.1568978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ICRU. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing I recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). ICRU Report 83. J ICRU 2010; 10: 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thor M, Petersen JBB, Bentzen L, Hyer M, Muren LP. Deformable image registration for contour propagation from CT to cone-beam CT scans in radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2011; 50: 918–25. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.577806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feuvret L, Nol G, Mazeron JJ, Bey P. Conformity index: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 64: 333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Son J, Baek T, Lee B, Shin D, Park SY, Park J, et al. A comparison of the quality assurance of four dosimetric tools for intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiol Oncol 2015; 49: 307–13. doi: 10.1515/raon-2015-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knöös T, Wieslander E, Cozzi L, Brink C, Fogliata A, Albers D, et al. Comparison of dose calculation algorithms for treatment planning in external photon beam therapy for clinical situations. Phys Med Biol 2006; 51: 5785. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/22/005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]