Abstract

The 18-kilodalton translocator protein (TSPO), proposed to be a key player in cholesterol transport into mitochondria, is highly expressed in steroidogenic tissues, metastatic cancer, and inflammatory and neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. TSPO ligands, including benzodiazepine drugs, are implicated in regulating apoptosis and are extensively used in diagnostic imaging. We report crystal structures (at 1.8, 2.4, and 2.5 angstrom resolution) of TSPO from Rhodobacter sphaeroides and a mutant that mimics the human Ala147→Thr147 polymorphism associated with psychiatric disorders and reduced pregnenolone production. Crystals obtained in the lipidic cubic phase reveal the binding site of an endogenous porphyrin ligand and conformational effects of the mutation. The three crystal structures show the same tightly interacting dimer and provide insights into the controversial physiological role of TSPO and how the mutation affects cholesterol binding.

The 18-kD translocator protein (TSPO) was first discovered as a receptor for benzodiazepine drugs in peripheral tissues and is implicated in transport of cholesterol into mitochondria, the first and rate-limiting step of steroid hormone synthesis (1, 2). TSPO is also a major research focus due to its apparent involvement in a variety of human diseases (3–5). Of particular interest is a human single-nucleotide polymorphism [rs6971 = Ala147→Thr147 (A147T) (6)] in a region of TSPO that is highly conserved between mammals and bacteria. The mutation is associated with diminished cholesterol metabolism (7), altered ligand binding to TSPO (8), and increased incidence of anxiety-related disorders in humans (9–11). Some understanding of how this mutation affects TSPO function has come from studies involving positron emission tomography (PET), which uses ligands of TSPO as sensitive imaging agents for detecting areas of inflammation in the brain (12). A lower binding affinity toward TSPO-specific PET ligands and an increased incidence of several neurological diseases correlate directly with the presence and dosage of the allele harboring the A147T mutation (9–11). This indicates that the TSPO mutation is responsible for the observed phenotypes, but it remains unclear how this mutation in TSPO alters cholesterol metabolism or how it is related to multiple neurological diseases.

Translocator protein from Rhodobacter sphaeroides (RsTSPO) has a 34% sequence identity with the human protein (fig. S1) and is the best-characterized bacterial homolog in the extensive TSPO family (13–15). Functional and mutational studies in R. sphaeroides show that RsTSPO is involved in porphyrin transport, as also reported in human (16), and in regulating the switch from photosynthesis to respiration in response to increased oxygen (13, 17, 18). The knock-out phenotype in R. sphaeroides can be rescued by the rat homolog (17), indicating conserved functional properties between bacterial and mammalian organisms and establishing the value of R. sphaeroides, a close living relative of the mitochondrion (19), as a model system to investigate structure-function relationships in TSPO.

The human mutation, A147T, is one helical turn preceding the cholesterol recognition consensus sequence (CRAC) identified as a cholesterol binding site in TSPO (20), suggesting that altered cholesterol binding could be involved. To test this hypothesis, the corresponding mutation, A139T, was created in RsTSPO, and the binding properties of the purified protein were compared with those of the wild type. The observed lower binding affinity (four- to fivefold) for cholesterol and PK11195, as well as protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) (Fig. 1A), is consistent with the phenotypic behavior of the human A147T polymorphism (7, 8), further confirming RsTSPO as a valuable model system and providing strong evidence of a functional defect caused by the mutation.

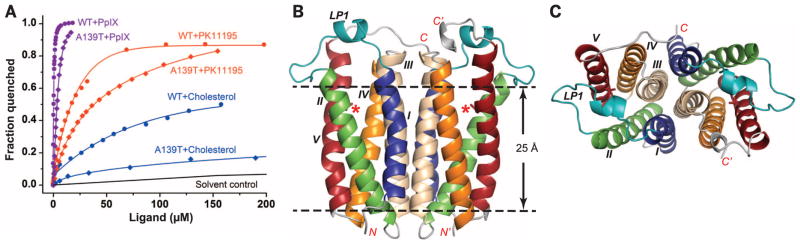

Fig. 1. Structure and ligand binding affinity of RsTSPO WT and the A139T mutant.

(A) Ligand binding affinities are shown for RsTSPO WT and the A139Tmutant mimicking the human A147Tmutation. Dissociation constant (Kd) values are obtained as described in (24): 10 ± 1 μM for PK11195 with WT, 42 ± 4 μM with A139T; 0.3 ± 0.01 μM for PpIX with WT, 1.9 ± 0.3 with A139T; and ~80 μM for cholesterol with WT, >300 μM with A139T. WT data are from (14), reproduced for comparison. (B) Overall structure of the A139T dimer. The position of the A139T mutation is labeled with a red asterisk and shown in sticks; the five transmembrane helices (TM-I to TM-V) are colored blue, green, wheat, orange, and red, respectively; and loop 1 (LP1) is colored teal. (C) Top view of (B). RsTSPO A139T crystallized in two different space groups (C2 and P212121) that have identical overall structures except for the flexible C terminus, whereas WTcrystallized in a P21 space group. In all three crystal forms, the identical parallel dimer of RsTSPO was observed (Fig. 2). The A139Tmutant in the C2 space group is shown here and used to discuss the major structural features of RsTSPO, as it has the highest resolution and most complete structure of RsTSPO. The N and C termini are labeled N/N′ and C/C′, respectively; the dashed lines highlight the approximate membrane region.

In line with these observations, crystal structures of the wild type (at 2.5 Å resolution) and the A139T mutant (at 1.8 and 2.4 Å resolution) show substantial differences within the CRAC site and conformational changes that alter the structural environment within a potential ligand binding region. Although crystallized in three different space groups (fig. S2), all RsTSPO structures show an identical “parallel” dimer formed from compact monomers composed of five transmembrane helices (Fig. 1, B and C). The residues within the CRAC site and surrounding the mutation are clearly resolved in all structures, including the wild-type (WT) protein and the A139T mutant (fig. S3 and table S1), providing the molecular basis for understanding the effect of this mutation.

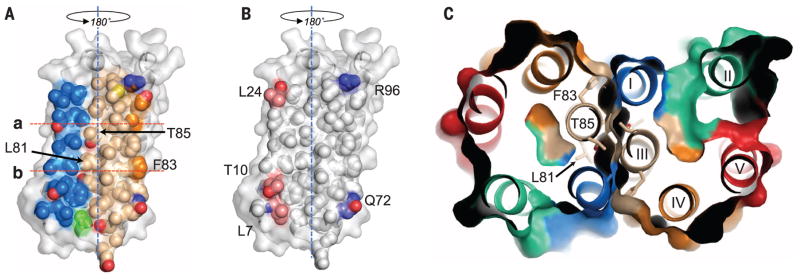

The dimer interface (Fig. 2) is primarily composed of 37 residues, contributed by transmembrane helices TM-III (16 residues), TM-I (12 residues), and TM-IV (3 residues) and covers ~1250 Å2 (~15% of a monomer’s surface area). The tight interface, unaltered by the mutation, is quite flat but displays two notable features. First, TM-III forms the central core of the hydrophobic interface, which is dominated by alanines and leucines, and reveals a G/A-xxx-G/A motif, which favors helical dimerization (21). Second, the central core of the interface is devoid of hydrogen bond interactions; the five observed hydrogen bonds are at the periphery between TM-I and TM-III. The tight fit suggests that the dimer interface is not likely to be a transport pathway (14). The biological relevance of a TSPO dimer is not well understood, but previous studies show that RsTSPO forms a stable dimer in detergent solution (14), and a similar dimeric structure is observed in the low-resolution cryo–electron microscopy (EM) structure (15) (fig. S4). Taken together, the dimer observed in these crystals is likely to be the primary structural and functional unit of RsTSPO. How the RsTSPO dimer is oriented in the Rhodobacter outer membrane is not well established and awaits further study.

Fig. 2. Analysis of the dimer interface.

(A) The dimer interface is primarily made up of TM-I and TM-III. Helices are colored the same as in Fig. 1 (blue, TM-I; gold, TM-III; orange, TM-IV) but are shown as space-filling models. TM-II and TM-IV make only minor contributions to the interface. Rotating the monomer by 180° about the dyad axis (blue dashed line) and overlaying it on top of itself creates the dimer. (B) Hydrophobic (white) and hydrogen bonding residues (blue, hydrogen bond donor atoms; red, hydrogen bond acceptor atoms) within the dimer interface. (C) Top view of a slab [between lines a and b in (A)]; residues forming strong interactions in the core of the dimer interface are labeled. The interface is essentially identical in all WTand A139Tstructures.

Recently, a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of the mouse TSPO (mTSPO) was determined in the presence of dodecylphoscholine (22). A monomeric species is observed with the same topology as the monomers in the crystal structures. However, the helices display substantial shifts in position and orientation relative to each other such that the overall tertiary structure is quite different (fig. S5). The major shifts in helix alignment in the NMR structure, particularly regarding TM-III, would markedly affect the dimer interface. Unlike the crystal structures, a stable tertiary structure for mTSPO is only achieved in the presence of PK11195 at a roughly fivefold molar excess, which may account for the distinctively different conformation observed.

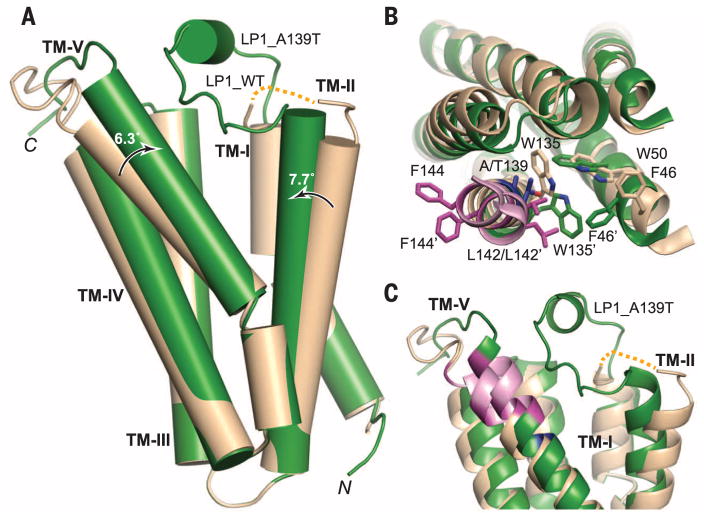

The structural differences between the WT and A139T proteins (Fig. 3 and fig. S6) are consistent with their differing ligand binding affinities (Fig. 1A). Superposition of the Cα atoms in the N-terminal side of each helix yields root mean square deviations of less than 0.3 Å. All of the major structural differences occur in the C-terminal side of the monomer, with helices TM-II and TM-V and loop 1 (LP-1) showing the most dramatic changes. TM-II tilts by 7.7° toward TM-V in the mutant structure, whereas TM-V becomes less kinked as the C-terminal portion of the helix straightens by 6.3°. This results in a closer association of TM-II and TM-V (Fig. 3A). TM-IV also shifts in concert with TM-V. In addition, the A139T mutation results in the movement and side-chain repositioning of F46 on TM-II, and L142 and F144 on TM-V, two of the critical residues of the CRAC (20) motif. The highly conserved W135 on TM-V is also flipped, resulting in a closer proximity to W50 on TM-II (Fig. 3B). These changes result in a substantially narrower gap between TM-II and TM-V in the A139T structure (fig. S7) and an altered surface in the CRAC region that may account for altered cholesterol and ligand binding.

Fig. 3. Structural comparison of WTand A139T RsTSPO.

Monomers of the WT (wheat) and A139T (green) are overlaid. (A) Overall structural alignment that highlights the degree and direction (arrows) of conformation change from WT to A139T for TM-II and TM-V. (B) Top view of the monomer, highlighting the side-chain rearrangements in sticks. Residue 139 is colored in blue; the CRAC site is colored in pink with two of three proposed critical residues (L142 and F144) highlighted in magenta. The prime symbol designates the mutant position. (C) Close-up side view of the potential ligand binding cavity, which reveals major differences in the conformations of LP1, TM-II, and TM-V between the WTand mutant proteins (fig. S7). The dotted yellow line denotes the location of unresolved LP1 in the WT structure (residues 29 to 40).

The relatively long linker LP1, which connects TM-I and TM-II (Fig. 1, B and C), is the only long loop in the entire structure and is proposed to play a role in ligand binding based on mutagenesis studies (2, 13). Within the loop is a short helical segment (residues 29 to 33) in monomers A and B of A139T in both C2 and P212121 crystal forms; in monomer C of the C2 form, the helical segment is unwound and results in a more extended LP1 (fig. S6). Although the LP1 is not completely resolved in the WT structure, its configuration is quite distinct from that of the mutant (Fig. 3C). As the RsTSPO structures determined here display three different well-resolved conformations of LP1 (fig. S6), this loop may exist in several defined states, consistent with the hypothesis that structural changes in LP1 play an important role in regulation of ligand binding and the functions of TSPO (2). Similarly, the 10 residues at the C terminus of TM-V take on several different conformations (fig. S6) that may also relate to different ligand binding states (23).

Ligands bind to RsTSPO less strongly than to the human protein (14), but RsTSPO still displays affinities for PpIX, PK11195, and cholesterol in the high nanomolar to micromolar range (14). Cholesterol was added to the crystallization medium, along with PK11195, but neither ligand was resolved, even though their addition did improve the quality of RsTSPO crystals (24). In monomer A of the A139T structure, a cavity between TM-I and TM-II and underneath LP1 contained electron density that did not fit any of the known components in the crystallization medium. However, it did correspond to the size and shape of a porphyrin ring (Fig. 4A). As porphyrins are proposed natural ligands for RsTSPO (13), and purified RsTSPO binds porphyrins tightly in vitro (14, 15), we identify the ligand in the A139T mutant as a porphyrin compound that copurifies with the protein (fig. S8, A and B).

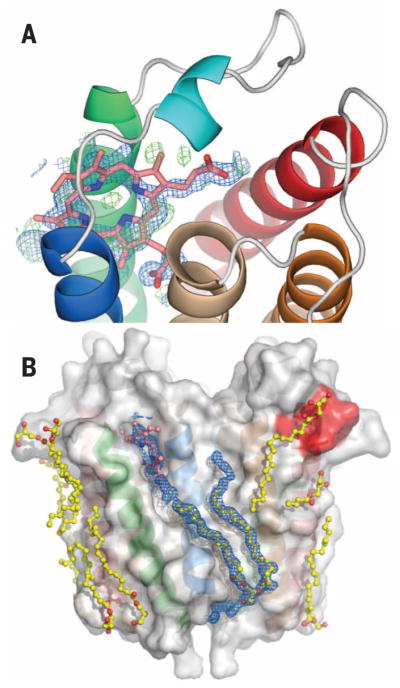

Fig. 4. Ligand binding and evidence for a transport pathway.

Close-up view of the porphyrin binding site (A) with a porphyrin (pink) overlaid with feature enhanced map (FEM) omit map electron density (blue) and Fo – Fc difference electron density (green), contoured at 1σ and ±3σ, respectively. A partially oxidized porphyrin is suggested by the spectrum (fig. S8A) that shows absence of a Soret band. (B) Surface groves on TSPO are occupied by monooleins and phospholipid (yellow). The CRAC site (red) is also interacting with lipids. Unusually long FEM omit map electron density (in blue and contoured at 1.0σ) extends from the porphyrin binding site to the bottom surface of the protein, beyond the bound phospholipid, suggesting an external transport pathway that involves both monomers of the dimer (see also fig. S9).

Lipids and considerable amounts of monoolein are observed in all three structures. The monooleins, which are primary components of the cubic-phase crystallization medium, most likely displace native lipids that would occupy the grooves on the protein’s surface (25), but the locations also provide insights into possible lipid and ligand binding sites. The polar head groups of the monooleins are observed in the porphyrin binding site in several monomers, whereas their lipidic tails lie along the surface grooves (fig. S8, C and D). The length of the electron density observed along several surface grooves in A139T is substantially longer than any known components of the crystallization conditions or Escherichia coli lipids (Fig. 4B and fig. S9), implying a continuous path occupied by several ligands or lipids bound in different positions. These observations suggest a possible sliding mechanism of transport (Fig. 4B and fig. S9E), similar to maltoporin (26) but on the external protein surface. Such a transport pathway would require the association of TSPO with itself or other protein partners. In fact, StAR and VDAC have been reported to associate with TSPO in a cholesterol transport complex (1), whereas oligomerization of mouse TSPO has been observed (27). The EM structure and the crystal-packing arrangements (fig. S4) also suggest possibilities for homo-oligomerization of the TSPO dimer. Models for TSPO-mediated ligand transport are somewhat constrained by the dimeric structure seen in RsTSPO crystals, making unlikely an internal pore-like transport mechanism (28) through the monomer or transport via the tight dimer interface (14). Thus, an external surface-transport mechanism appears worthy of further investigation.

Based on the structures of RsTSPO, WT, and A139T determined in this study and current understanding of TSPO function, we propose that the phenotype of the A147T mutation in humans arises from altered cholesterol binding and transport caused by the perturbed environment around the CRAC site, which modifies the binding surface for cholesterol. Concurrently, the changes in the tilt of the helices give rise to reduced binding of other ligands, suggesting that the A147T mutation overall favors a lower-affinity conformation. A proposed external surface-transport mechanism that probably requires protein partners is consistent with the complex functional and regulatory properties of this ancient multifaceted protein (29–32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under identification numbers 4UC3 (WT), 4UC1 (A139T_C2), and 4UC2 (A139T_P212121). We thank S. Kaplan, X. Zeng (University of Texas, Houston), and A. Yeliseev (NIH) for providing the expression plasmid; R. M. Stroud, J. Lee, and members of the University of California, San Francisco, Membrane Protein Expression Center (NIH grant GM094625 to R. M. Stroud) for initial collaboration on the project and training on the lipidic cubic phase crystallization method, as well as continued support and discussion; M. Caffrey and D.-F. Li for helpful discussion of selenomethionine phasing strategies and supplying some noncommercial lipids; and A. Kruse and C. Wang for suggestions on data collection and heavy-metal soaking strategies. We also thank B. Atshaves, C. Najt, and L. Valls for assistance in obtaining the fluorescence quenching data; C. Hiser and N. Bowlby for technical assistance in protein expression and purification and careful reading of the manuscript; K. Parent for discussion on analyzing the EM map; and C. Ogata, R. Sanishvili, N. Venugopalan, M. Becker, and S. Corcoran at beamline 23ID at GM/CA CAT Advanced Photon Source, as well as M. Soltis, C. Smith, and A. Cohen at BL12-2 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source, for assistance and consultation. Funding was provided by NIH grant GM26916 (to S.F.-M.) and Michigan State University Strategic Partnership Grant, Mitochondrial Science and Medicine (to S.F.-M.). GM/CA@APS has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (grant ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant AGM-12006). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fan J, Papadopoulos V. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e76701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan J, Lindemann P, Feuilloley MG, Papadopoulos V. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:369–386. doi: 10.2174/1566524011207040369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird JL, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:388–391. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardwick M, et al. Cancer Res. 1999;59:831–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji B, et al. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12255–12267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2312-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

- 7.Costa B, et al. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5438–5445. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen DR, et al. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1–5. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colasanti A, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2826–2829. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura K, et al. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:222–226. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa B, et al. Psychiatr Genet. 2009;19:110–111. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32832080f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreisl WC, et al. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:53–58. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeliseev AA, Kaplan S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5657–5667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Xia Y, Meiler J, Ferguson-Miller S. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5884–5899. doi: 10.1021/bi400431t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korkhov VM, Sachse C, Short JM, Tate CG. Structure. 2010;18:677–687. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeno S, et al. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:494–501. doi: 10.2174/1566524011207040494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeliseev AA, Krueger KE, Kaplan S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5101–5106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeliseev AA, Kaplan S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21234–21243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esser C, Martin W, Dagan T. Biol Lett. 2007;3:180–184. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Papadopoulos V. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4991–4997. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DT, Berger BW, DeGrado WF. Structure. 2008;16:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaremko L, Jaremko M, Giller K, Becker S, Zweckstetter M. Science. 2014;343:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.1248725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farges R, et al. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 25.Qin L, Hiser C, Mulichak A, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16117–16122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutzler R, Schirmer T, Karplus M, Fischer S. Structure. 2002;10:1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delavoie F, et al. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4506–4519. doi: 10.1021/bi0267487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lacapère JJ, Papadopoulos V. Steroids. 2003;68:569–585. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatliff J, Campanella M. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:356–368. doi: 10.2174/1566524011207040356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scarf AM, et al. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:488–493. doi: 10.2174/156652412800163460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rupprecht R, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:971–988. doi: 10.1038/nrd3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morohaku K, et al. Endocrinology. 2014;155:89–97. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.