Abstract

Cells precisely control the formation of dynamic actin cytoskeletal networks to coordinate fundamental processes including motility, division, endocytosis and polarization. To support these functions, actin filament networks must be assembled, maintained and disassembled at the correct time and place, and with proper filament organization and dynamics. Regulation of the extent of filament network assembly and their organization have been largely attributed to the coordinated activation of actin assembly factors through signalling cascades. Here we discuss an intriguing model in which actin monomer availability is limiting, and competition between homeostatic actin cytoskeletal networks for actin monomers is an additional crucial regulatory mechanism that influences density and size of different actin networks, thereby contributing to the organization of the cellular actin cytoskeleton.

Introduction

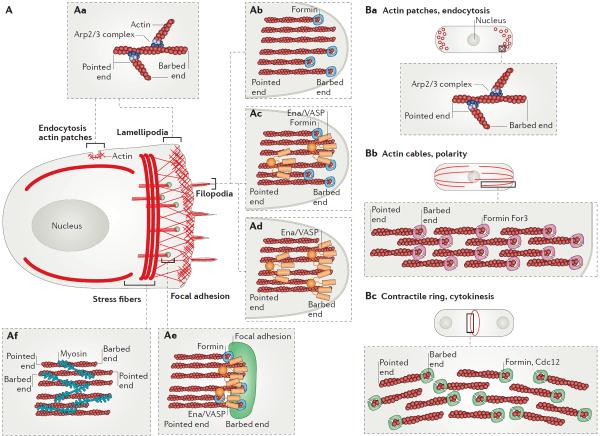

Cells coordinate the formation of diverse actin filament (F-actin) networks from a general cytoplasmic pool of components including monomeric actin (G-actin) at the correct time and place to facilitate crucial events such as cytokinesis, motility and endocytosis (Figure 1). F-actin adopts two main architectures whose formation is mediated by distinct actin nucleators. The Arp2/3 complex facilitates the formation of dense branched F-actin networks that are necessary to generate pushing forces capable of deforming the cell membrane to promote processes like motility and endocytosis (Figure 1 A–a, B–a). Conversely, formins and Ena/VASP assemble straight F-actin that can be bundled to create networks such as the cytokinetic contractile ring, membrane-protruding filopodia, or polarizing F-actin bundles (Figure 1 A–b, A–c, A–d, B–b, B–c). F-actin networks adopt specific architectures and dynamics dictated by the action of diverse sets of specific actin binding proteins (ABPs) to perform their particular cellular tasks (Figure 1)1,2.

Figure 1. Functionally diverse F-actin networks in mammalian and fission yeast cells.

(A) Representative F-actin network organization in a motile mammalian cell. (Aa) Arp2/3 complex generates branched F-actin networks such as lamellipodia and endocytic vesicles. (Ab – Ae) Formin and Ena/VASP assemble F-actin found in linear bundles such as filopodia (Ab – Ad) or focal adhesions (Ae). (Af) Myosin motors are associated with contractile antiparallel F-actin bundles including stress fibers. (B) Fission yeast cells contain three principal F-actin networks generated by different actin assembly factors. (Ba) Arp2/3 complex generates branched F-actin networks for endocytic actin patches. (Bb) Formin For3 generates parallel F-actin bundles for polarizing actin cables. (Bc) Formin Cdc12 generates antiparallel F-actin bundles for the cytokinetic contractile ring.

The size and density of F-actin networks appears to be critical for their proper function. For example, fission yeast contains three major F-actin networks, each composed of F-actin generated by a specific actin assembly factor (Figure 1B). Endocytic actin patches require the Arp2/3 complex, whereas the formins Cdc12 and For3 assemble F-actin for the cytokinetic contractile ring and polarizing actin cables1. The amount of actin incorporated into endocytic patches and the contractile ring is remarkably consistent from network to network and cell to cell, varying less than 50% between each structure3,4. Furthermore, experimental manipulation of the size of actin networks typically correlates with functional defects. For example, depletion of the formin mDia2 causes a 20% decrease of F-actin in the contractile ring of fibroblasts, which is coupled with cytokinesis defects5. Localized inhibition of Arp2/3 complex induces a change in direction of cell motility in fish keratocytes6, while general disruption of the Arp2/3 complex in fibroblasts coincides with the disappearance of lamellipodia7–12, a decrease in cell migration speed7,12 and cell spreading efficiency10. Interestingly, this decrease in migration speed was not observed in ARPC3−/− (depletion of Arp2/3 complex) fibroblasts but instead the motility directionality was severely decreased, indicating that various cells can also respond differently to the perturbation of their actin networks11. As another example, expression of constitutively active formin constructs in budding yeast increases actin cable number and causes defects in polarized cell growth13,14.

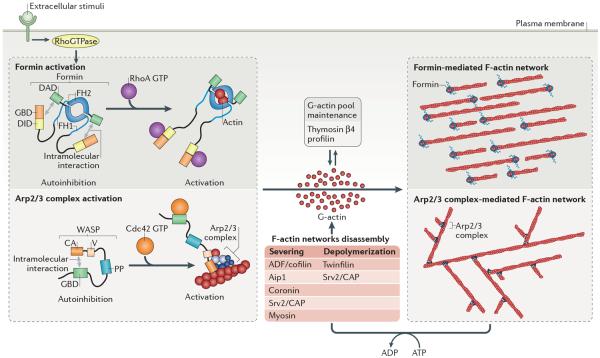

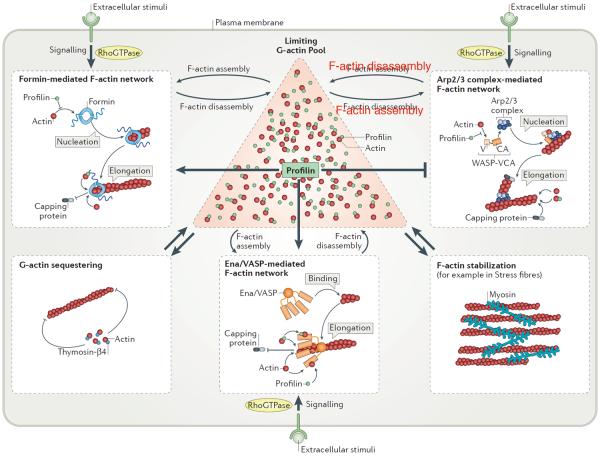

How does the cell generate diverse F-actin networks of proper functional sizes within a common cytoplasm? It has been largely accepted that the amount of actin assembly is regulated primarily by activation of actin assembly factors via signalling cascades such as those involving Rho GTPases (Figure 2). Here we offer an updated model, whereby the free cytoplasmic G-actin content is limited and therefore becomes depleted as cytoskeletal networks grow, thereby limiting the size and density of other (competing) F-actin networks. The release of G-actin through network disassembly is thus critical to promote the subsequent growth of other co-existing and the assembly of new networks. Collectively, we propose that F-actin networks exist in homeostasis, whereby their size is controlled, at least in part, through this competition. Traditionally actin homeostasis has referred to the general ratio of G- to F-actin2, without taking into account that F-actin is distributed between distinct networks with different functions. Regulation of diverse actin networks through competition for G-actin has received little attention, but a substantial amount of recent experimental data indicates that competition is in fact an important additional regulator of actin cytoskeletal network size, thereby supporting our model.

Figure 2. Classic model of F-actin network regulation.

Signalling cues bind membrane receptors activating RhoGTPase signaling pathways. RhoGTPases activate actin assembly factors directly, with Rho GTP directly relieving autoinhibition of formin, or indirectly through nucleation promoting factors like WASP, which activates Arp2/3 complex following its own activation induced by Cdc42 GTP binding. Actin assembly factors then facilitate the nucleation and/or elongation of G-actin into branched (Arp2/3 complex) or linear (formin) actin filaments. A reserve of unassembled actin is maintained by proteins that prevent nucleation (profilin), or nucleation and elongation (Thymosin β4). F-actin networks `age' through ATP hydrolysis to ADP on actin monomers incorporated into the filament, which leads to filament disassembly. Disassembly of filaments is also facilitated by a suite of severing and depolymerizing factors and this depolymerization collectively replenishes the pool of G-actin. Arp2/3 complex, actin related protein 2 and 3 complex; GBD, GTPase-binding domain; DID, DAD interacting domain; DAD, Diaphanous autoregulatory domain; FH1, Formin homology 1; FH2, Formin homology 2; V, WH2 domain; CA, Acidic domain; PP, Polyproline domain; AIP1, Actin-interacting protein 1; CAP, adenylyl cyclase-associated protein (also known as Srv2).

[H1] Classic view of actin turnover

Here, we define F-actin network size as the number of actin subunits a network contains. A network's size is determined by the cumulative difference between the amount of incorporation and dissociation of G-actin, which in turn is controlled by regulating actin assembly factors through signaling pathways (Figure 2). F-actin polymerization occurs principally by addition of ATP-bound G-actin to the dynamic barbed end in comparison to the slow growing pointed end15. Upon barbed end subunit addition, ATP is hydrolyzed rapidly (Half-life of ~2 seconds) to become ADP-Pi16. A slower release of Pi follows (Half-life of ~6 minutes), resulting in ADP-F-actin15. F-actin elongates and the network expands by addition of ATP-G-actin onto free barbed ends (Figure 2), whereas `older' ADP-F-actin networks are disassembled by severing and depolymerization (Figure 2). These aspects are described in Box I.

The initiation of F-actin network assembly is primarily controlled by signalling pathways and in the classical view it is believed that signalling principally regulates actin cytoskeleton organization by promoting polymerization within defined networks. Signals initiate from external stimuli such as cell-cell junctions and chemical cues (Figure 2), or internal stimuli such as activation of formin-mediated F-actin assembly by mictrotubules17–20. Because the main actin assembly factors - the Arp2/3 complex and formins - are normally inhibited and therefore intrinsically inactive, unwanted F-actin assembly is prevented from occuring (Figure 2). Only upon localized activation mediated by small Rho GTPases do these proteins engage in actin polymerisation, and this controls spatial and temporal F-actin network assembly (Figure 2)21–24. Three well-studied Rho GTPases (Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA) are all involved in actin nucleator activation. For example, Rac1 and Cdc42 release the inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex activators WAVE and WASP (Figure 2)21,25–27. Conversely, RhoA releases autoinhibition of some formins such as mDia1 (Figure 2)24,28,29.

It has to be, however, noted that the role of signalling pathways in actin assembly regulation is much more complicated than described here - it can be highly context dependent and a considerable amount of crosstalk between different pathways can occur. For example, Cdc42 can activate both Arp2/3 complex and the formin FMNL1 in macrophages, whereas Rac1 may activate both WAVE and Dictyostelium discoideum formin dDia230,31.

[H1] Competition for the G-actin pool

Apart from signalling, other factors and mechanisms can potentially contribute to regulating actin polymerization within networks and can impact the distribution of actin between them. As the total amount of actin synthesized in a given cell is believed to remain constant32, it is possible that co-existing F-actin networks are engaged in a competitive crosstalk, whereby they compete for a limiting pool of G-actin. Although some data suggest that G-actin is not limiting (see discussion), there is a growing body of evidence that internetwork competition for G-actin is important. We therefore further propose a new model of the regulation of cellular F-actin networks, where in addition to signalling-based actin regulators, competition between homeostatic F-actin networks for a limited amount of G-actin is critical for regulating their size and density33.

[H3] Basic concept of internetwork competition

The concept that a limiting number of building blocks contributes to the regulation of the size and density of organelles, such as centrosomes, flagella and mitotic and meiotic spindles is well documented and has been the subject of several recent reviews34,35. In these examples, the limited availability of components typically restricts the size or density of a specific organelle or structure (such as a mitotic spindle or the nucleus). A limited actin pool represents a more sophisticated mechanism of size regulation, since functionally diverse networks with different architectures compete for the same resource.

In addition to the classic signalling-based hypothesis of actin turnover (Figure 2), we propose a modified model including competition for G-actin that posits that generation of new F-actin networks also depends on the disassembly of older networks to regenerate the G-actin pool. For example, the size of the G-actin pool has been shown to be important for multiple actin-based processes such as migration of PtK2 cells and the in vitro reconstituted motility of the bacterium Listeria monomcytogenes36,37. The concentration of G-actin is crucial for F-actin network assembly since the nucleation rate of assembly factors like Arp2/3 complex and formin is enhanced with an increase in the concentration of free G-actin29,38. Furthermore, an experimental increase of G-actin concentration induces Arp2/3 complex- and formin-mediated actin assembly in fission yeast and fibroblasts, resulting in a two-fold increase of Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin patches and a five-fold increase in processive formin-mDia1 molecules, respectively33,39–41.

If homeostatic F-actin networks compete for G-actin, a simple prediction is that disruption of one network will increase the amount of G-actin consumed by the remaining networks (Figure 3A–B). A systematic test of competition between F-actin networks has recently been performed in fission yeast33. There are, however, numerous other examples published over the last twenty years, which indicate that modification of the amount of F-actin in one type of network has an effect on the size and density of other networks, suggesting competitive crosstalk between the networks. These examples are briefly described below.

Figure 3. Disassembly of F-actin networks releases G-actin that accumulates in remaining networks.

a–b Cartoon illustrating our model of F-actin network homeostasis. Network sizes are simulated deterministically using coupled rate equations, and each network is distinguished by a set of parameter values. The starting values of fraction of total actin are based on estimates from fission yeast33. As these graphs are illustrative, time is presented in arbitrary units. (a) Model of actin reorganization upon branched network disassembly. The disassembly of an Arp2/3 complex network (branched F-actin) via genetic or small molecule inhibitor perturbation releases a pool of G-actin that will incorporate into remaining formin- and or Ena/VASP-mediated linear F-actin networks. Through Arp2/3 complex-mediated branched F-actin network disassembly, G-actin concentration will initially increase, and then is followed by a reduction due to its incorporation in remaining F-actin networks. (b) Model of actin homeostasis during cytokinetic ring assembly and disassembly. Assembly of the formin-mediated contractile ring requires a reduction in Arp2/3 complex-mediated F-actin networks (such as endocytic actin patches in fission yeast). The amount of F-actin incorporated into the ring will equal its decrease in actin patches. After ring disassembly, the level of actin consumed by actin patches is restored. In this example the assembly of a formin-mediated contractile ring during mitosis coincides with a partial disassembly of Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic actin patches, necessary for the incorporation of G-actin in the formin-mediated contractile ring. (c–e) Examples of F-actin network homeostasis in cells and in vivo evidence for internetwork competition. (c) Fission yeast expressing the general F-actin marker Lifeact-GFP. Wild type cells (left panel) contain three principal F-actin networks: endocytic actin patches (Arp2/3 complex), polarizing actin cables and contractile rings (formins). Inhibition of Arp2/3 complex by the small molecule inhibitor CK-666 induces disappearance of patches coupled with an accumulation of actin in formin-associated networks (middle panel). Genetic inhibition of formin-mediated F-actin networks induces an increase in the number of Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic patches (right panel). Images were adapted with permissions from REF33. (d) A fibroblast expressing the general F-actin marker Lifeact-GFP. Disappearance of lamellipodia by Arp2/3 complex sequestration through injection of the acidic domain (WCA) of WAVE1 in the presence of constitutively active Rac1 (WCA/Rac) induces an increase in formin- and/or and Ena/VASP-generated filopodia. Images were adapted with permissions from REF47. (e) A Drosophila S2 culture cell expressing Actin-GFP. Inhibition of Arp2/3 complex by dsRNA ARP2 induces a disappearance of Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia, and an increase in Ena/VASP- and/or formin-mediated mediated filopodia formation. Images were adapted with permissions from REF51.

[H3] Experimental evidence for competition

Modification of actin incorporation into dendritic networks generated by the Arp2/3 complex directly influences actin incorporation into linear networks, generated by formins and Ena/VASP. As shown in yeast, pharmacological depletion of Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic actin patches causes a 20-fold increase in actin assembled into formin-associated actin cables and contractile rings (Figure 3C)33,42,43. Conversely, increasing endocytic actin patch number by overexpressing the Arp2/3 complex activator Las17 decreases formin-mediated actin cables by 40%13. Similarly, modification of formin-mediated actin assembly affects Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks. Inhibition of formin and disappearance of their associated networks (contractile ring and polarizing actin cables) increases the consumption of actin by Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin patches by 50% (Figure 3 C)33,44,45. Overexpressing constitutively active formin stimulates the excessive formation of formin-mediated cables coupled with a 35% decrease in Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic patches13. Notably, the aforementioned studies have been performed with a large range of fluorescent F-actin labels (Lifeact, phalloidin, calponin homology domain, antibodies, actin fused with fluorescent proteins), excluding the possibility that the reported phenotypes are simply due to unintended artifacts caused by F-actin biomakers46.

F-actin network homeostasis is also important in multicellular systems, and inhibition of Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks often leads to an increase in the density of formin- and/or Ena/VASP-mediated structures, such as filopodia (Figure 3 D–E). For example, depletion or inactivation of Arp2/3 complex in fibroblasts results in the disappearance of lamellipodia and an increase in filopodia formation, likely by incorporation of the released pool of G-actin by formin or Ena/VASP (Figure 3 D)7,12,47,48. A similar Arp2/3 complex inactivation phenotype has also been reported in other cell types such as Drosophila S2, human osteosarcoma U2OS, rat adenocarcinoma MTLn3, Coelomocytes and Aplysia neuronal growth cones (Figure 3 E)49–54. Interestingly, in Aplysia neuronal growth cones, Arp2/3 complex inhibition does not increase the length of filopodia, but instead the rate of both filopodia elongation and retrograde flow are increased54. An increase in G-actin concentration after Arp2/3 complex inhibition could account for this phenotype. This example suggests that competition between F-actin networks for G-actin is relevant even without changes in filament length and corresponding network size, and therefore competition for G-actin may be critical for most F-actin networks. For example, microvilli, which are dependent upon F-actin assembled by the WH2 domain family actin assembly factor Cordon-bleu, are longer when Arp2/3 complex is inhibited55.

In addition to the interference with distinct F-actin networks, disruption of the F-actin disassembly mediated by ADF/cofilin also impacts the reincorporation of G-actin into different networks, most likely through the interference with the proper regeneration of the G-actin pool (alternatively, ADF/cofilin is also thought to have a direct role in F-actin assembly by generating new barbed ends through severing56,57). For example, F-actin severing by ADF/cofilin has been shown to promote the formation of migratory cell lamellipodium in mammalian cells58,59. On the other hand, in fission yeast depletion of ADF/cofilin prevented endocytic actin patch disassembly and contractile ring assembly33,60.

In these examples from yeast and animal cells, actin assembly factor activity was artificially modulated (Figure 3 C–E). An important question is whether cells utilize competition to intrinsically regulate F-actin dependent processes. It appears likely, as the assembly of formin-mediated contractile rings during division in fission yeast correlates with a decrease in actin incorporated in Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic actin patches61. Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to determine how cells utilize homeostasis-driven internetwork competition to regulate F-actin assembly. Additional studies are also required to determine whether other actin regulators, such as the ABP profilin12,39, may also be limiting and contribute to the size regulation of competing networks.

[H1] Mediators of competition

If F-actin networks are in competition for a limited pool of G-actin, how do cells actively tune this competition to spatially and temporally favour particular networks? Activation of actin nucleators at particular times and places via distinct signalling pathways (Figure 2) presumably plays a major role in how cells regulate competition between F-actin networks. For example, specific formin isoforms are activated during mitosis to generate the cytokinetic contractile ring1,62 and must compete with other F-actin networks for G-actin to ensure robust assembly of the ring. A major question then is how G-actin is properly distributed between F-actin networks competing for the pool of monomers. Potentially, any ABP that differentially affects competitive F-actin networks could have a role in this process and mediate the competition and its outcome. We focus below on profilin, capping protein and myosin II because of recent evidence of their participation in F-actin network competition, but we suspect that other actin regulators are also important.

[H3] Role of profilin

Recent articles highlight the contribution of the small ABP profilin as a major contributor to the proper segregation of G-actin between competing networks. Profilin has long been considered as a general actin cytoskeleton housekeeping protein that helps maintain a pool of unpolymerized actin that is equally utilizable by diverse F-actin networks2. However, recent work revealed that through opposing effects on competing actin assembly factors, profilin potentially constitutes a molecular switch that mediates network competition. Profilin enhances formin-mediated actin elongation up to 15-fold (Figure 4)63–65, and may slightly increase Ena/VASP-mediated filament elongation66–68. Conversely, profilin inhibits Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation (branch formation) (Figure 4)12,39,69–71. Therefore presence of high levels of profilin favors G-actin incorporation into F-actin networks consisting of linear F-actin such as formin-generated filaments in the contractile ring and polarizing actin cables in fission yeast or filopodial protrusions in fibroblasts made by Ena/VASP proteins (Figure 4)12,39.

Figure 4. Updated model of F-actin homeostasis including internetwork competitive crosstalk.

Extracellular stimuli activate RhoGTPase signaling pathways that activate formin-, Arp2/3 complex- or Ena/VASP-mediated F-actin networks, promoting actin assembly within these networks. These networks remain in competition with each other for G-actin from a common limited pool (red triangle). Actin associated with sequestering proteins or incorporated in other networks (such as stress fibers stabilized by myosin motors), cannot participate in competition and largely affect the internetwork competition by further restricting the amount of actin available for polymerization. Profilin favours incorporation of G-actin into formin- and Ena/VASP-dependent F-actin networks (but at the same time inhibits formin-mediated nucleation of new filaments), while inhibiting Arp2/3 complex activation via competing with WASP-VCA for G-actin binding, and tips the balance towards the formation of linear actin networks. Capping protein competes with formin and Ena/VASP for barbed ends, whereas capping protein rapidly binds free barbed ends generated by Arp2/3 complex. Disassembly of F-actin networks replenishes the G-actin pool allowing more robust polymerization and growth of networks.

Interestingly, overexpression of profilin favours the formation of formin-mediated contractile rings, whereas the overexpression of actin favors the formation of Arp2/3 complex-mediated patches33,39. These experiments indicate that the ratio of profilin to G-actin may govern the competition between Arp2/3 complex- and formin-mediated F-actin networks. Two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to the inhibition of Arp2/3 complex-mediated branch formation by profilin. First, profilin directly competes with the Arp2/3 complex activator WASP for binding to G-actin39,71,72, although this mechanism may not explain the full extent of Arp2/3 complex inhibition70. Second, profilin association with F-actin barbed ends may inhibit Arp2/3 complex binding70, and thereby Arp2/3 activity and branching at barbed ends; however the generally accepted view is that branches are primarily formed from the side of actin filaments rather than the barbed end15. In addition, phosphorylation of mouse Profilin-1 at Tyr 129 increases its affinity to G-actin and its ability to compete with actin sequestering thymosin-β4 for G-actin73, a mechanism that is expected to further contribute to favouring formin over Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin assembly by profilin. At extremely high concentrations, free profilin may also compete with barbed end binding proteins such as capping protein, formin and Ena/VASP70, thereby allowing profilin to similarly inhibit competing actin assembly factors. However, the concentrations of profilin and unassembled G-actin in most cell types are similar15,39, which is why profilin likely favors formin and Ena/VASP over Arp2/3 complex in most cells12,39.

We propose that regulation of profilin activity and/or localization likely represents an important mechanism by which cells control the balance between Arp2/3 complex- and formin (or Ena/VASP)-mediated F-actin assembly. For example, fission yeast profilin appears to be locally concentrated at the tips of interphase cells, thereby potentially favoring formin For3- over Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin assembly at these sites61. Similarly, profilin may be more concentrated at the division site of dividing fission yeast cells, facilitating formin Cdc12-mediated actin assembly61. In fibroblasts, profilin may be enriched at the Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia74, where it could limit Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation, thereby regulating extension of these protrusions. Most multi-cellular eukaryotes express multiple profilin isoforms that are expressed at different times and cellular locations as well as show tissue-specific expression. At the same time these different isoforms have been differentially tailored to facilitate actin assembly for distinct F-actin networks75,76. Further experiments will be necessary to determine if and how cells actively modulate profilin activity to govern F-actin network competition.

Linear versus dendritic array competition involves barbed end capping

Barbed end cappers, such as the capping protein, are important regulators of F-actin network size (Figure 4). Capping protein has a high affinity for free F-actin barbed ends (~ 0.1 nM)77, competing with formin and Ena/VASP for F-actin barbed ends66,78–81 and promoting formation of short-branched filaments in Arp2/3 complex-mediated F-actin networks15. Interestingly, deletion of capping protein in budding and fission yeast increases actin incorporation into Arp2/3 complex-mediated patches by at least 35%82–85. Capping protein localizes to Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin patches, where it presumably associates with F-actin barbed ends and keeps filaments short by terminating their elongation (Figure 4). In the absence of barbed end capping, the uninterrupted growth of F-actin is expected to rapidly deplete the monomer pool, presumably decreasing the availability of G-actin for formin-dependent processes. In agreement, the number of formin-mediated actin cables decreases dramatically in the absence of capping protein in fission yeast and budding yeast82,85,86. However, the function of capping protein may be more complicated and might be context dependent, as its depletion in melanoma cells and neurons decreases F-actin in Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia and increases formin- and Ena/VASP-mediated filopodia number 5-fold87,88, contrary to what has been observed in yeast. In line with this, capping protein has been proposed to enhance Arp2/3 complex-mediated branching by steering monomers to new branch nuclei rather than existing barbed ends89.

It is possible that the observed differences in the role of capping protein in regulating the size of competing networks depends on whether or not the competing Arp2/3 complex- and formin- or Ena/VASP-mediated networks are physically linked. An example of such physically linked networks are found in migratory protrusions in mammalian cells, where filopodia are thought to elongate from the lamellipodia90. In this case, inhibition of capping protein may facilitate recruitment of Ena/VASP and formin to branched networks, which would subsequently drive actin assembly into linear networks and filopodia extension, thereby decreasing G-actin pool available for Arp2/3 complex. Regulation of capping protein activity might therefore also be critical for balancing competitive F-actin networks. Notably, cells harbor various regulators of capping protein, including steric inhibitors like the protein myotrophin/V1 or phospholipids PtdIns(4,5)P2, which bind directly to Capping Protein and inhibit its capping activity91. Furthermore, localization and activity of capping protein can be influenced by association with CARMIL (capping protein, Arp2/3 complex and myosin I linker) proteins, which contain a capping protein interaction motif92.

[H3] Actomyosin networks contribute to internetwork competition

The molecular motor myosin II, which associates with F-actin to form contractile, actomyosin bundles such as cell stress fibers, may also be an important regulator of F-actin network homeostasis, and thus may influence internetwork competition. A recent study uncovered a competitive relationship between Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks and actomyosin networks in epithelial cells, which may help regulate the transition from static to migratory polarized epithelial cells93. Inhibition of non-muscle myosin II by the small molecule inhibitor blebbistatin increases the concentration of G-actin by approximately 50% within 15 min, which is subsequently consumed by Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks to trigger cell polarization and motility (Figure 4). These observations may be relevant since non-muscle myosin II can be activated or inhibited by phosphorylation of specific residues in both its regulatory light chain and heavy chain94. In addition to its important role in force generation, myosin may therefore be a molecular switch that controls the assembly of actin into actomyosin bundles over Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia formation. In addition to myosin, another component of actomyosin bundles, tropomyosin, contributes to the competitive crosstalk between actin networks. For example, In general, tropomyosins appear to be important regulators of actin filament identity and dynamics, and have been implicated in inhibiting cofilin-mediating binding and severing95. In addition, tropomyosins have been suggested to bind preferentially to formin- over Arp2/3 complex-mediated F-actin networks96,97, and microinjection of skeletal tropomyosin into PtK1 epithelial cells has been shown to inhibit Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia while promoting filopodia formation98.

[H1] Homeostatic control of actin

Traditionally, actin homeostasis has referred to the maintenance of a stable, ratio of total F- to G-actin in cells2. The principal driving force of F-actin network formation is the signalling pathway-mediated spatial and temporal activation of actin assembly factors. However, how the signalling activates particular networks leading to their expansion, at the same time allowing the maintenance of actin homeostasis has remained elusive.

[H3] A model of homeostatic internetwork competition for G-actin

Based on recent observations from primary data discussed above, we propose here an updated view of actin homeostasis, whereby competition between co-existing actin networks for a limited G-actin pool is an additional, important factor regulating the distribution of actin between these networks, and thus also their relative growth and size (Figures 3 and 4). We propose that owing to the limited G-actin availability, in order to support growth of defined networks activated assembly factors require constant replenishment of G-actin, which occurs though G-actin release by the steady disassembly of other existing networks15. In our model, this internetwork competition for limited G-actin is critical for regulating F-actin network size and density, and can be influenced by specific regulatory ABPs. Because profilin inhibits Arp2/3 complex-mediated branching while enhancing formin-mediated elongation, and formin and Ena/VASP antagonize capping protein, profilin and capping protein prevent G-actin incorporation into Arp2/3 complex-mediated F-actin networks more than formin- and Ena/VASP-mediated F-actin networks12,39,80,81,83–85. Myosin can stabilize and sequester actin subunits in F-actin network reserves, which upon signaling can release G-actin quickly that subsequently incorporates into Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia that triggers polarized epithelial cell motility93,94. We therefore hypothesize that modulating the activity of these different ABPs by signalling pathways could serve to direct the assembly of actin into specific F-actin networks.

[H3] Alternative possibilities and validity of the proposed model

The model we propose here provides an attractive explanation of homeostatic control of F-actin networks in vivo. However, future studies are needed to better understand the principles governing regulated distribution of actin between coexisting networks.

It has been traditionally thought that the number of free F-actin barbed ends, not the G-actin pool, is the limiting factor for the regulation of F-actin network size and density. For example, Acanthamoeba castellanii and neutrophil extracts contain filaments that do not elongate because their barbed ends are strongly capped and addition of activated Rho GTPase Cdc42 to these extracts triggers Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation of new branched filaments that rapidly assemble99,100. This indicates that the limitation of barbed end availability might indeed play an important role in regulating network size. It is, however, noteworthy that this regulatory mechanism is not in direct contradiction with our model and both mechanisms might be at play in vivo.

Our model of F-actin network competition for a limited pool of G-actin postulates that the amount of actin incorporated into one network will indirectly and inversely influence actin incorporation into other networks, thereby affecting their size. However, this relationship between F-actin networks was not observed in several studies. For example, in melanoma B16-F1 cells, the induced disappearance of Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia, by RNAi knockdown of WAVE or Arp2/3 complex does not appear to modify the number of Ena/VASP- and/or formin-generated filopodia9. In Jurkat T cells, the inhibition of Arp2/3 complex via the small molecule inhibitor CK-666 induces a significant decrease in formin-mediated filopodia formation101. In Drosophila Dm-BG2-c2 cells, knockdown of the Arp2/3 complex activator SCAR leads to a disappearance of the lamellipodia coupled with an eight-fold decrease in total F-actin concentration, suggesting that G-actin released by disassembled lamellipodia is not fully reincorporated into the remaining F-actin networks such as filopodia102. Finally, in Dictyostelium discoideum, depletion of the formin forA, which generates F-actin networks at the cell cortex, is coupled with an increase in cell motility rate103. The authors concluded that the motility rate increase was dependent on myosin II activity, rather than a rise of actin incorporation into Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks. It is thus possible that the increase of G-actin concentration is not sufficient alone to incorporate into existing F-actin networks.

So how can these observations be reconciled in light of the model we propose? It might be that internetwork competition for G-actin may not contribute to actin network regulation in all systems and/or cellular contexts, perhaps because actin is not limiting in all systems or additional regulatory mechanisms are at play that dilute the importance of G-actin limitation. For example, in the lamellipodia of differentiated neuroblastoma cells, G-actin bound to thymosin-β4 targets formin-mediated polymerization instead of Arp2/3 complex, indicating that the ratio of G-actin to G-actin binding proteins including profilin and thymosin-β4 is a critical buffer of changes in unpolymerized actin104. It is also likely that the nature (associated time-scale in particular) of the methods used to inhibit particular actin network could impact their effects on F-actin network competition and therefore the final phenotype observed. Long-term perturbations, such as genetic mutants, could allow adaptations (such as changes in actin expression) over numerous generations that mask homeostatic competition. Conversely, acute perturbations such as small molecule inhibitors, will likely elicit only short-lasting homeostatic responses, which can be overlooked or misinterpreted. As an example of different phenotypes resulting from distinct perturbations, rapid small molecule inhibition of Arp2/3 complex in fission yeast has a much stronger and evident effect on the formation of additional formin-mediated networks in comparison with Arp2/3 complex deletion in the mutants33. It is also possible that some perturbations to the actin cytoskeleton are efficiently buffered, counter-balanced by additional mechanisms, or cannot be easily detected owing to the nature and/or complexity of the particular redistribution event. For example, it is possible that in some conditions release of G-actin from inhibited Arp2/3 complex networks is redistributed to multiple formin- and Ena/VASP-mediated F-actin networks such as focal adhesion (Figure 1 A–e) and stress fibers (Figure 1 A–f) that are not as easily quantifiable as filopodia (Figure 1 A–b, A–c, A–d). Additionally, it has been reported that Arp2/3 complex-mediated F-actin network formation may be necessary to generate the barbed ends used to form filopodia90, and can account for an observed decrease in filopodia formation upon Arp2/3 complex inhibition.

[H1] Conclusions and perspectives

Altogether we have outlined here the novel idea that G-actin is a limiting resource in F-actin network assembly. We propose that in addition to signalling pathways, internetwork competition for this limited pool regulates network size and density. We further suggest that specific ABPs, by modulating filament assembly and disassembly rates, influence the efficiency of actin incorporation into competing networks, thereby serving as mediators (or effectors) of internetwork competition. This new competitive F-actin network homeostasis model generates several challenging questions that remain to be addressed. For example, the concept of homeostasis-driven internetwork competition for G-actin has emerged based on experiments involving artificial manipulations of F-actin networks through inhibitory drugs and genetic approaches (Figure 3 C–E). Therefore, an important question is whether competition for G-actin to favour the assembly of particular networks underlies inherent, physiological processes, such as actin cytoskeleton remodeling upon initiation or cessation of cell migration. A good model to start addressing the importance of internetwork competition in the physiological context is cytokinetic contractile ring formation during mitosis in fission yeast, where approximately 20% of the F-actin content has to be redistributed from Arp2/3 complex-mediated endocytic patches to the formin-generated contractile ring33,61. During this process, is the activation of formin by signalling sufficient to allow effective competition for G-actin with pre-existing Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks, or is a reduced amount of Arp2/3 complex activation also necessary? It will also be important to quantitatively measure how redistribution of actin to competing networks affects the loss or incorporation of ABPs into the competing networks. Do F-actin networks that expand by inhibition of competing networks incorporate more ABPs? Conversely, what happens to ABPs from inhibited networks? Finally, what are the regulatory mechanisms governing segregation of ABPs to diverse F-actin networks in cells?

Bearing in mind the important role of ABPs and their regulation for the competitive crosstalk between actin networks, it is also possible that ABPs function context-specifically, and that different ABPs are required for distinct responses. In vivo and in vitro experiments have revealed that profilin favours the assembly of formin- and Ena/VASP- over Arp2/3 complex-mediated networks (Figure 4)12,39 and cells could potentially temporally and spatially activate profilin via signalling pathways, phosphorylation and sequestration to elicit the desired changes in actin cytoskeleton organization. Furthermore, different isoforms of profilin, formin or Arp2/3 complex subunits are present in cells and may be more or less tailored for competition in different contexts. Nevertheless, it is currently not known how the cell regulates the activities of these proteins to control the size of specific networks at any given time. The next challenge will be to determine if such regulatory mechanisms exist and how they are employed to facilitate growth of particular F-actin networks.

We also predict that the contribution of ABPs to internetwork competition may be species dependent. For example, in worms, profilin is able to stimulate F-actin elongation rates mediated by cytokinesis-specific formin CYK-1 up to 6-fold more strongly than in the case of equivalent formin Cdc12 from fission yeast105. Hence, it is possible that the impact of profilin on the competition between formin and Arp2/3 complex in these two species differs. In addition, the particular profilin to actin ratio or profilin binding affinity to actin may alter profilin's contribution to competition. It will be thus very interesting to investigate how expression levels of various ABPs contribute to actin network homeostasis,

Homeostasis-driven internetwork competition for G-actin also suggests that the expression level of actin may be critical. For example, inducing five-fold changes in actin expression dramatically tips the balance of network formation in fission yeast cells33,39. Overexpressing actin favors Arp2/3 complex, whereas lowering actin expression favours formin, which appears to be largely due to altering the ratio of actin to profilin39. Surprisingly, these drastic variations of actin expression levels impact only the number of Arp2/3 complex endocytic patches, not their size33. It would be interesting to investigate how cells maintain a constant size of these structures in such different conditions. Perhaps actin expression is carefully monitored and tightly regulated in cells so that competition for G-actin can be utilized to facilitate the assembly of particular F-actin networks as cells respond to changing needs. It will be now important to study in more detail how cells respond to changes in actin expression, how robustly they can maintain homeostasis upon changes in actin levels and whether they can actively control actin expression to regulate network competition.

Our competition model also predicts that F-actin network assembly in a cell may be perturbed upon infection with bacterial pathogens including Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and Rickettsia species, which rely on actin-mediated motility and hijack host actin to generate F-actin networks driving their own propulsion106–108. It will be interesting to determine whether and how these bacteria efficiently compete with host cell F-actin networks for a limited pool of G-actin. It has been reported that Listeria cells move slower in host cell compartments containing dense F-actin networks109, indicating that indeed in this context competition for G-actin might be at play and that incorporation of actin into host networks locally depletes G-actin pool, thereby restricting bacterial propulsion.

An extremely interesting question is whether competition between F-actin networks provides any additional benefit for the cell compared to regulation of network density and size by signalling alone. One possibility is that competition allows for consistent F-actin elongation rates and allows cells to maintain a constant G-actin concentration, without the need for unnecessary and slow changes in actin expression levels. A limited pool of G-actin also avoids excessive F-actin assembly without requiring concomitant inhibition through signalling pathways, since assembly rates into networks will naturally decrease as the cytoplasmic G-actin concentration decreases in response to. In addition, competition mediated by ABPs such as profilin and thymosin-β4 may be necessary to ensure that formin- and Ena/VASP-mediated F-actin networks can still be generated in the presence of excess Arp2/3 complex12,39,104 – a scenario likely observed in most cells. Furthermore, the rapid generation of G-actin upon acute disassembly of F-actin networks, such as through inhibition of myosins or activation of ADF/cofilin, may be necessary for rapid transitions between static and motile cells93 (Figure 4).

Finally, the homeostatic F-actin network competition model has significant repercussions for interpreting experiments where actin assembly factors and/or their associated F-actin networks are disrupted using small molecule inhibitors or genetic approaches. For example, disruption of Arp2/3 complex-mediated lamellipodia leads to an increase of filopodia at the leading edge of migrating cells7,12,48. One interpretation may be that Arp2/3 complex-generated branched actin filaments are not critical for filopodia assembly9. Alternatively, it is possible that the release of excess G-actin through Arp2/3 complex inhibition artificially leads to ectopic formin- and/or Ena/VASP-mediated filopodia by alternative mechanisms. Care must therefore be taken when interpreting experiments that interfere with the physiological homeostatic balance of actin and we think that considering the possibility of the existence of the competitive crosstalk between networks can bring novel understanding of experimental data.

Box 1: Principles of F-actin assembly and disassembly.

Network assembly

Actin polymerization occurs predominantly at F-actin barbed ends. The barbed end elongation rate, konG, is proportional to the monomer concentration (G, in μM), where kon is the actin assembly rate constant and is equal to 11.6 μM−1s−1 15. The G-actin concentration, not incorporated into F-actin, varies broadly in different cell types from less than 25 μM in budding yeast and fission yeast to more than 100 μM in higher eukaryotes15,33,39,110. In addition, several G-actin-binding proteins can largely impact the fraction of polymerizable monomers, thereby regulating G-actin availability. In vertebrate cells, thymosin-β4 and profilin are present at a range of concentrations (25–500 μM for thymosin-β4 and 5–100 μM for profilin) and compete for ATP-G-actin binding (Figure 2)111–115. Whereas thymosin-β4 sequesters G-actin, inhibiting its spontaneous nucleation and its addition on filament ends113,115,116, profilin-bound G-actin constitutes the major pool of polymerizable actin117. Profilin inhibits both the spontaneous nucleation of new filaments and the addition of G-actin into F-actin pointed ends118, but G-actin bound to profilin incorporates onto pre-existing F-actin barbed ends at approximately the same rate as free G-actin118,119. In lower eukaryotes thymosin-β4 is absent, and therefore the majority of G-actin is bound to profilin.

Above the critical concentration, where the concentration G-actin is in equilibrium with F-actin, filament elongation persists until the barbed end is capped, preventing further addition or loss of actin subunits. Capping protein is the major player in this process and binds tightly to F-actin barbed ends (Kd ~ 0.1 nM)77. Arp2/3 complex is bound to the pointed end of the nucleated filament, and therefore cannot protect its barbed ends from capping protein. Conversely, both formin and Ena/VASP associate with and protect barbed ends from capping protein120–122. Recent studies revealed that capping protein and formin can bind simultaneously to F-actin barbed ends in a `decision complex', competitively increasing each other's dissociation rates by at least 2- and 7-fold, respectively80,81.

Actin network expansion is driven by the generation of new barbed ends. New F-actin barbed ends can be generated from three different sources: de novo nucleation, severing, and uncapping of pre-existing filaments. Actin nucleation factors such as the Arp2/3 complex, formins and WH2 domain-containing nucleators facilitate the generation of new actin nuclei123–126. Production of new ends by severing pre-existing filaments is primarily facilitated by ADF/cofilin, which preferentially binds to and severs older ADP-loaded portions of F-actin127–129. Lastly, F-actin barbed ends previously blocked by capping can be uncapped by proteins such as CARMIL, which increases the dissociation rate of capping protein up to 180-fold (Half-time of 10 seconds)130. Accordingly, the average half time of capping protein on F-actin barbed ends in XTC fibroblast is three orders of magnitudes shorter than measured in vitro (approximately 1 second and 1,800 seconds respectively)131.

Network disassembly

The size and density of an actin network will be inevitably affected by the disassembly of F-actin. The F-actin severing property of ADF/cofilin promotes the rapid disassembly of F-actin networks (Figure 2)15,58,132,133. The additional action of Coronin increases ADF/cofilin association rate with F-actin134,135, whereas actin-interacting protein 1 (Aip)1 and adenylyl cyclase-associated protein Srv2/CAP increase the rate of cofilin-mediated severing (Figure 2)134,136–138.

The rate of actin dissociation from F-actin ends can also be increased, resulting in filament disassembly. The barbed end depolymerization rate is increased ~3-fold by twinfilin, whereas in combination with Srv2/CAP, pointed end depolymerization increases an additional 17-fold139. Interestingly, different F-actin networks disassemble at different rates, which influences the recycling of G-actin140. For example, in XTC fibroblasts, the majority of F-actin in stress fibers disassembles five times slower than in other fibers, whereas F-actin in filopodia disassembles 2.4 times slower than in lamellipodia140. The coordinated actions of these diverse disassembly factors allow for rapid actin disassembly, replenishing the G-actin pool for subsequent network assembly (Figure 2).

As the filament elongation rate is directly proportional to the concentration of polymerizable monomers, the rate that F-actin is recycled into G-actin has the potential to directly influence subsequent network assembly. Therefore, the alterations of the disassembly machinery within one network can potentially feed back onto the polymerization rates and thus affect the size of this as well as other co-existing F-actin networks.

Altogether, the combined action of these actin binding proteins will control the proportion of polymerizable G-actin, of free barbed ends and the regeneration rate of the G-actin pool by F-actin disassembly.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick McCall (The University of Chicago) and members of the Kovar laboratory including Jonathan Winkelman, Jenna Christensen and Thomas Burke (The University of Chicago), for helpful discussion and comments. Work on actin cytoskeleton regulation in the Kovar lab is supported by NIH grant R01 GM079265. Cristian Suarez has also been supported in part by DOD/ARO through a MURI grant, number W911NF1410403.

Biographies

Cristian Suarez Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA.

Cristian Suarez obtained his Ph.D. from University Joseph Fourier, Grenoble, 38041 Isère, France, and is currently a postdoctoral associate at The University of Chicago, Illinois, USA, the Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology. His interests lie in the molecular mechanisms of actin cytoskeleton self-organization.

David R. Kovar Departments of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology and of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA.

David R. Kovar obtained his Ph.D. from Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA, and is currently a professor at The University of Chicago, Illinois, USA in the Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology and of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. His lab studies the molecular mechanisms by which cells self-organize the actin cytoskeleton.

Footnotes

Authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kovar DR, Sirotkin V, Lord M. Three's company: the fission yeast actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J. Actin Dynamics, Architecture, and Mechanics in Cell Motility. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:235–263. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirotkin V, Berro J, Macmillan K, Zhao L, Pollard TD. Quantitative analysis of the mechanism of endocytic actin patch assembly and disassembly in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2894–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J-Q, Pollard TD. Counting Cytokinesis Proteins Globally and Locally in Fission Yeast. Science. 2005;310:310–314. doi: 10.1126/science.1113230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe S, et al. mDia2 induces the actin scaffold for the contractile ring and stabilizes its position during cytokinesis in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:2328–2338. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang I, et al. Inhibitory signalling to the Arp2/3 complex steers cell migration. Nature. 2013;503:281–284. doi: 10.1038/nature12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu C, et al. Arp2/3 Is Critical for Lamellipodia and Response to Extracellular Matrix Cues but Is Dispensable for Chemotaxis. Cell. 2012;148:973–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machesky LM, Insall RH. Scar1 and the related Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein, WASP, regulate the actin cytoskeleton through the Arp2/3 complex. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1347–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steffen A, et al. Filopodia Formation in the Absence of Functional WAVE- and Arp2/3-Complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:2581–2591. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson-Dykstra SM, Higgs HN. Arp2 depletion inhibits sheet-like protrusions but not linear protrusions of fibroblasts and lymphocytes. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:904–922. doi: 10.1002/cm.20312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suraneni P, et al. The Arp2/3 complex is required for lamellipodia extension and directional fibroblast cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:239–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotty JD, et al. Profilin-1 Serves as a Gatekeeper for Actin Assembly by Arp2/3-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. Dev. Cell. 2015;32:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L, Bretscher A. Analysis of unregulated formin activity reveals how yeast can balance F-actin assembly between different microfilament-based organizations. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1474–1484. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sagot I, Klee SK, Pellman D. Yeast formins regulate cell polarity by controlling the assembly of actin cables. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:42–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard TD, Blanchoin L, Mullins RD. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:545–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD. Hydrolysis of ATP by Polymerized Actin Depends on the Bound Divalent Cation but Not Profilin †. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2002;41:597–602. doi: 10.1021/bi011214b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin SG, Rincón SA, Basu R, Pérez P, Chang F. Regulation of the formin for3p by cdc42p and bud6p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:4155–4167. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin SG, McDonald WH, Yates JR, III, Chang F. Tea4p Links Microtubule Plus Ends with the Formin For3p in the Establishment of Cell Polarity. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piekny A, Werner M, Glotzer M. Cytokinesis: welcome to the Rho zone. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rincón SA, et al. Pob1 Participates in the Cdc42 Regulation of Fission Yeast Actin Cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4390–4399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eden S, Rohatgi R, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Kirschner MW. Mechanism of regulation of WAVE1-induced actin nucleation by Rac1 and Nck. Nature. 2002;418:790–793. doi: 10.1038/nature00859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung DW, Rosen MK. The nucleotide switch in Cdc42 modulates coupling between the GTPase-binding and allosteric equilibria of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:5685–5690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406472102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otomo T, Otomo C, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Rosen MK. Structural Basis of Rho GTPase-Mediated Activation of the Formin mDia1. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe N, et al. p140mDia, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila diaphanous,is a target protein for Rho small GTPase and is a ligand for profilin. EMBO J. 1997;16:3044–3056. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Activation by Cdc42 and Pip2 of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein (Wasp) Stimulates Actin Nucleation by Arp2/3 Complex. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1311–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohatgi R, et al. The Interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 Complex Links Cdc42-Dependent Signals to Actin Assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alberts AS. Identification of a Carboxyl-terminal Diaphanous-related Formin Homology Protein Autoregulatory Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2824–2830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Higgs HN. The mouse Formin mDia1 is a potent actin nucleation factor regulated by autoinhibition. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schirenbeck A, Bretschneider T, Arasada R, Schleicher M, Faix J. The Diaphanous-related formin dDia2 is required for the formation and maintenance of filopodia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:619–625. doi: 10.1038/ncb1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seth A, Otomo C, Rosen MK. Autoinhibition regulates cellular localization and actin assembly activity of the diaphanous-related formins FRLα and mDia1. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:701–713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leavitt J, et al. Expression of transfected mutant beta-actin genes: alterations of cell morphology and evidence for autoregulation in actin pools. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:2457–2466. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burke TA, et al. Homeostatic Actin Cytoskeleton Networks Are Regulated by Assembly Factor Competition for Monomers. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan Y-HM, Marshall WF. How cells know the size of their organelles. Science. 2012;337:1186–1189. doi: 10.1126/science.1223539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goehring NW, Hyman AA. Organelle Growth Control through Limiting Pools of Cytoplasmic Components. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:R330–R339. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cramer LP. Role of actin-filament disassembly in lamellipodium protrusion in motile cells revealed using the drug jasplakinolide. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier M-F. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature. 1999;401:613–616. doi: 10.1038/44183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgs HN, Blanchoin L, Pollard TD. Influence of the C terminus of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) and the Arp2/3 complex on actin polymerization. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 1999;38:15212–15222. doi: 10.1021/bi991843+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suarez C, et al. Profilin Regulates F-Actin Network Homeostasis by Favoring Formin over Arp2/3 Complex. Dev. Cell. 2015;32:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higashida C, et al. G-actin regulates rapid induction of actin nucleation by mDia1 to restore cellular actin polymers. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3403–3412. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higashida C, et al. F- and G-actin homeostasis regulates mechanosensitive actin nucleation by formins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:395–405. doi: 10.1038/ncb2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basu R, Chang F. Characterization of Dip1p Reveals a Switch in Arp2/3-Dependent Actin Assembly for Fission Yeast Endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakano K, Kuwayama H, Kawasaki M, Numata O, Takaine M. GMF is an evolutionarily developed Adf/cofilin-super family protein involved in the Arp2/3 complex-mediated organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Cytoskeleton. 2010;67:373–382. doi: 10.1002/cm.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jose M, et al. A quantitative imaging-based screen reveals the exocyst as a network hub connecting endo- and exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:2519–34. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willet AH, et al. The F-BAR Cdc15 promotes contractile ring formation through the direct recruitment of the formin Cdc12. J. Cell Biol. 2015;208:391–399. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201411097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courtemanche N, Pollard TD, Chen Q. Avoiding artefacts when counting polymerized actin in live cells with LifeAct fused to fluorescent proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ncb3351. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koestler SA, et al. Arp2/3 complex is essential for actin network treadmilling as well as for targeting of capping protein and cofilin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2013;24:2861–2875. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-12-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suraneni P, et al. A Mechanism of Leading Edge Protrusion in the Absence of Arp2/3 Complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:901–12. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henson JH, et al. Arp2/3 Complex Inhibition Radically Alters Lamellipodial Actin Architecture, Suspended Cell Shape, and the Cell Spreading Process. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:887–900. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hotulainen P, Lappalainen P. Stress fibers are generated by two distinct actin assembly mechanisms in motile cells. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:383–394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ingerman E, Hsiao JY, Mullins RD. Arp2/3 complex ATP hydrolysis promotes lamellipodial actin network disassembly but is dispensable for assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:619–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers SL, Wiedemann U, Stuurman N, Vale RD. Molecular requirements for actin-based lamella formation in Drosophila S2 cells. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1079–1088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarmiento C, et al. WASP family members and formin proteins coordinate regulation of cell protrusions in carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:1245–1260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Q, Zhang X-F, Pollard TD, Forscher P. Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin networks constrain myosin II function in driving retrograde actin flow. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:939–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grega-Larson NE, Crawley SW, Erwin AL, Tyska MJ. Cordon bleu promotes the assembly of brush border microvilli. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:3803–3815. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-06-0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Q, Pollard TD. Actin filament severing by cofilin is more important for assembly than constriction of the cytokinetic contractile ring. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:485–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh M, et al. Cofilin Promotes Actin Polymerization and Defines the Direction of Cell Motility. Science. 2004;304:743–746. doi: 10.1126/science.1094561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiuchi T, Ohashi K, Kurita S, Mizuno K. Cofilin promotes stimulus-induced lamellipodium formation by generating an abundant supply of actin monomers. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiuchi T, Nagai T, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. Measurements of spatiotemporal changes in G-actin concentration reveal its effect on stimulus-induced actin assembly and lamellipodium extension. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:365–380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakano K, Mabuchi I. Actin-depolymerizing protein Adf1 is required for formation and maintenance of the contractile ring during cytokinesis in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1933–1945. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balasubramanian MK, Hirani BR, Burke JD, Gould KL. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc3+ gene encodes a profilin essential for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:1289–1301. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balasubramanian MK, Bi E, Glotzer M. Comparative Analysis of Cytokinesis in Budding Yeast, Fission Yeast and Animal Cells. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R806–R818. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kovar DR, Harris ES, Mahaffy R, Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Control of the Assembly of ATP- and ADP-Actin by Formins and Profilin. Cell. 2006;124:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Romero S, et al. Formin is a processive motor that requires profilin to accelerate actin assembly and associated ATP hydrolysis. Cell. 2004;119:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Higashida C, et al. Actin Polymerization-Driven Molecular Movement of mDia1 in Living Cells. Science. 2004;303:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1093923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barzik M, et al. Ena/VASP Proteins Enhance Actin Polymerization in the Presence of Barbed End Capping Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28653–28662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503957200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pasic L, Kotova T, Schafer DA. Ena/VASP Proteins Capture Actin Filament Barbed Ends. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9814–9819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710475200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hansen SD, Mullins RD. VASP is a processive actin polymerase that requires monomeric actin for barbed end association. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:571–584. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Machesky LM, et al. Scar, a WASp-related protein, activates nucleation of actin filaments by the Arp2/3 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pernier J, Shekhar S, Jegou A, Guichard B, Carlier M-F. Profilin Interaction with Actin Filament Barbed End Controls Dynamic Instability, Capping, Branching, and Motility. Dev. Cell. 2016;36:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodal AA, Manning AL, Goode BL, Drubin DG. Negative regulation of yeast WASp by two SH3 domain-containing proteins. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marchand J-B, Kaiser DA, Pollard TD, Higgs HN. Interaction of WASP/Scar proteins with actin and vertebrate Arp2/3 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:76–82. doi: 10.1038/35050590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan Y, et al. Stimulus-dependent phosphorylation of profilin-1 in angiogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buss F, Temm-Grove C, Henning S, Jockusch BM. Distribution of profilin in fibroblasts correlates with the presence of highly dynamic actin filaments. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1992;22:51–61. doi: 10.1002/cm.970220106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mouneimne G, et al. Differential Remodeling of Actin Cytoskeleton Architecture by Profilin Isoforms Leads to Distinct Effects on Cell Migration and Invasion. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:615–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neidt EM, Scott BJ, Kovar DR. Formin Differentially Utilizes Profilin Isoforms to Rapidly Assemble Actin Filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:673–684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schafer DA, Jennings PB, Cooper JA. Dynamics of capping protein and actin assembly in vitro: uncapping barbed ends by polyphosphoinositides. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winkelman JD, Bilancia CG, Peifer M, Kovar DR. Ena/VASP Enabled is a highly processive actin polymerase tailored to self-assemble parallel-bundled F-actin networks with Fascin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322093111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bear JE, et al. Antagonism between Ena/VASP Proteins and Actin Filament Capping Regulates Fibroblast Motility. Cell. 2002;109:509–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shekhar S, et al. Formin and capping protein together embrace the actin filament in a menage a trois. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8730. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bombardier JP, et al. Single-molecule visualization of a formin-capping protein /`decision complex/' at the actin filament barbed end. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8707. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amatruda JF, Cannon JF, Tatchell K, Hug C, Cooper JA. Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton in yeast capping protein mutants. Nature. 1990;344:352–354. doi: 10.1038/344352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berro J, Pollard TD. Synergies between Aip1p and capping protein subunits (Acp1p and Acp2p) in clathrin-mediated endocytosis and cell polarization in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:3515–3527. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim K, Yamashita A, Wear MA, Maéda Y, Cooper JA. Capping protein binding to actin in yeast biochemical mechanism and physiological relevance. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:567–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kovar DR, Wu J-Q, Pollard TD. Profilin-mediated Competition between Capping Protein and Formin Cdc12p during Cytokinesis in Fission Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2313–2324. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sizonenko GI, Karpova TS, Gattermeir DJ, Cooper JA. Mutational analysis of capping protein function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:1–15. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mejillano MR, et al. Lamellipodial Versus Filopodial Mode of the Actin Nanomachinery: Pivotal Role of the Filament Barbed End. Cell. 2004;118:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sinnar SA, Antoku S, Saffin J-M, Cooper JA, Halpain S. Capping protein is essential for cell migration in vivo and for filopodial morphology and dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:2152–2160. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-12-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Akin O, Mullins RD. Capping Protein Increases the Rate of Actin-Based Motility by Promoting Filament Nucleation by the Arp2/3 Complex. Cell. 2008;133:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Svitkina TM, et al. Mechanism of filopodia initiation by reorganization of a dendritic network. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:409–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Edwards M, et al. Capping protein regulators fine-tune actin assembly dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:677–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edwards M, McConnell P, Schafer DA, Cooper JA. CPI motif interaction is necessary for capping protein function in cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8415. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lomakin AJ, et al. Competition for actin between two distinct F-actin networks defines a bistable switch for cell polarization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:1435–1445. doi: 10.1038/ncb3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gunning PW, Hardeman EC, Lappalainen P, Mulvihill DP. Tropomyosin – master regulator of actin filament function in the cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. jcs. 2015:172502. doi: 10.1242/jcs.172502. doi:10.1242/jcs.172502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson M, East DA, Mulvihill DP. Formins Determine the Functional Properties of Actin Filaments in Yeast. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1525–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hsiao JY, Goins LM, Petek NA, Mullins RD. Arp2/3 Complex and Cofilin Modulate Binding of Tropomyosin to Branched Actin Networks. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:1573–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gupton SL, et al. Cell migration without a lamellipodium. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mullins RD, Pollard TD. Rho-family GTPases require the Arp2/3 complex to stimulate actin polymerizationin Acanthamoeba extracts. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zigmond SH, et al. Mechanism of Cdc42-induced Actin Polymerization in Neutrophil Extracts. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:1001–1012. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Young LE, Heimsath EG, Higgs HN. Cell type-dependent mechanisms for formin-mediated assembly of filopodia. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:4646–59. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-09-0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Biyasheva A, Svitkina T, Kunda P, Baum B, Borisy G. Cascade pathway of filopodia formation downstream of SCAR. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:837–848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ramalingam N, et al. A resilient formin-derived cortical actin meshwork in the rear drives actomyosin-based motility in 2D confinement. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8496. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vitriol EA, et al. Two Functionally Distinct Sources of Actin Monomers Supply the Leading Edge of Lamellipodia. Cell Rep. 2015;11:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Neidt EM, Skau CT, Kovar DR. The Cytokinesis Formins from the Nematode Worm and Fission Yeast Differentially Mediate Actin Filament Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23872–23883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gouin E, Welch MD, Cossart P. Actin-based motility of intracellular pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Haglund CM, Choe JE, Skau CT, Kovar DR, Welch MD. Rickettsia Sca2 is a bacterial formin-like mediator of actin-based motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:1057–1063. doi: 10.1038/ncb2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Madasu Y, Suarez C, Kast DJ, Kovar DR, Dominguez R. Rickettsia Sca2 has evolved formin-like activity through a different molecular mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:E2677–E2686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307235110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]