Abstract

Introduction

The REGAL (RSV Evidence—a Geographical Archive of the Literature) series provide a comprehensive review of the published evidence in the field of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in Western countries over the last 20 years. This second publication covers the risk and burden of RSV infection in preterm infants born at <37 weeks’ gestational age (wGA) without chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken for articles published between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2015. Studies reporting data for hospital visits/admissions for RSV infection among preterm infants as well as studies reporting RSV-associated morbidity, mortality, and risk factors were included. Study quality and strength of evidence (SOE) were graded using recognized criteria.

Results

2469 studies were identified of which 85 were included. Preterm infants, particularly those born at lower wGA, tended to have higher RSV hospitalization (RSVH) rates compared with otherwise healthy term infants (high SOE). RSVH rates ranged from ~5 per 1000 children to >100 per 1000 children with the highest rates shown in the lowest gestational age infants (high SOE). Independent risk factors associated with RSVH include: proximity of birth to the RSV season, living with school-age siblings, smoking of mother during pregnancy or infant exposure to environmental smoking, reduced breast feeding, male sex, and familial atopy (asthma) (high SOE). Predictive models can identify 32/33–35 wGA infants at risk of RSVH (high SOE).

Conclusion

RSV infection remains a major burden on Western healthcare systems and is associated with significant morbidity. Further studies focusing on the prevalence and burden of RSV in different gestational age cohorts, the changing risk of RSVH during the first year of life, and on RSV-related mortality in preterm infants are needed to determine the true burden of disease.

Funding

AbbVie.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40121-016-0130-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Burden, Gestational age, Hospitalization, Immunoprophylaxis, Preterm, Respiratory syncytial virus, Risk

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most important cause of severe respiratory infection in infants, leading to over 3 million hospitalizations worldwide each year [1]. By 2 years of age, almost all children have been infected with RSV at least once [2]. Although the majority of severe cases occur among previously healthy term infants [3, 4], clinical studies have shown that infants with a history of prematurity are at higher risk of RSV infection requiring hospitalization than infants born at term [4, 5]. The risks relate to anatomic factors including small lung volumes, a reduced lung surface area, small airways, an increased air space wall thickness, and lower levels of maternally transmitted antibodies [6]. Although prematurity alone can significantly increase the risk for severe RSV disease, the presence of one or more other socioeconomic and environmental risk factors may also increase an infant’s susceptibility to severe RSV disease and subsequent hospitalization [7–12]. Every year, an estimated 15 million infants are born preterm (before 37 completed weeks of gestation), and according to the World Health Organization, this number is rising [13]. In developed countries, almost 9% of all live births annually are estimated to be preterm, with those born between 32 and 37 weeks’ gestational age (wGA) representing the majority (>80%) of preterm infants [13].

Care of preterm infants with severe RSV disease places a substantial burden on pediatric hospital resources each winter [14]. Data from a 2003 retrospective study suggest that prematurity ≤35 wGA is a risk factor for greater use of hospital resources and poorer clinical outcomes during hospitalization for severe RSV infection [14]. In addition, RSV infection in preterm infants has been associated with chronic respiratory morbidity and increased healthcare costs [15–19]. Currently, no effective vaccine against RSV exists, but RSV immunoprophylaxis is available for certain high-risk groups to prevent RSV disease. A number of underlying risk factors that significantly increase the risk of RSV hospitalization (RSVH) in preterm infants have been identified [20], most notably from the Spanish FLIP (Factors that most Likely may lead to development of RSV related respiratory Infection and subsequent hospital admission among Premature infants born 33–35 wGA) [7, 8] and the Canadian PICNIC (The Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada) [9] studies. Many of these risk factors have been used to inform national guidance on the optimal use of RSV immunoprophylaxis in different countries including the United States (US) [21], Canada [22], Spain [23] and Italy [24].

The prevention of RSV in preterm infants, however, continues to be a challenge. A greater awareness of the relative importance of prematurity as a risk factor for severe RSV disease is essential in order to improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. To provide a comprehensive understanding of severe RSV disease in preterm infants, an expert panel, comprising Neonatologists, Pediatricians, Pediatric Infectious Disease Specialists, Pediatric Cardiologists and Pediatric Pulmonologists from the US, Canada and Europe, undertook an evidence-based search of the literature which has accumulated over the past two decades. The primary objective of RSV Evidence—a Geographical Archive of the Literature (REGAL) was to carry out a series of systematic reviews and then to assess, quantify, summarize and grade the evidence base for severe RSV infection in Western societies. By undertaking this review, our current understanding of RSV was defined as well as, importantly, gaps in our knowledge and future areas of research.

This paper, which represents the second in a series of seven publications covering a range of topics on RSV disease, identifies and describes the risks and associated morbidity and mortality of severe RSV infection requiring hospitalization in preterm infants without chronic lung disease (CLD)/bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or congenital heart disease (CHD) in Western societies.

Methods

The primary objective of REGAL was to address seven specific research questions. The systematic reviews undertaken to answer each research question all used the same broad methodology, which has been described elsewhere [25]. The full protocol and generic search terms for the systematic reviews are available as part of the online supplement. In brief, we conducted a systematic and comprehensive search of medical literature electronically indexed in PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and clinicaltrials.gov. We used a detailed search strategy and combined free-text search terms with Medical Subject Headings. To ensure that the literature search was manageable, only studies conducted in Western countries were included, defined as the US, Canada, and Europe (including Turkey and the Russian Federation).

The search for this systematic review included studies conducted in children (defined as ≤18 years old) and published between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2015. The target population was preterm infants born at less than 37 wGA without CLD or CHD (or studies with mixed populations of healthy preterm infants and preterm infants, some with comorbidities) who had ‘proven’ or ‘probable’ RSV and had or had not received RSV immunoprophylaxis. Other significant studies of the target population, published during the drafting of the manuscript, were also included in the review, as identified by the authors.

In this systematic literature review, we sought to answer the two following questions:

What is the predisposition and associated morbidity, long-term sequelae and mortality of preterm infants (<37 wGA) without CLD, BPD or CHD, overall, and split by gestational age segments, to severe RSV infection?

What are the risk factors associated with RSVH?

We used the following general terms and limits: “RSV” OR “respiratory syncytial virus” AND “preterm” OR “premature” OR “gestational age” OR “gestation” AND “hospitalization” AND “hospitalization” OR “predisposition” OR “risk factor” AND “limits: human, child (birth to 18 years)”. The search results were supplemented by review of the bibliographies of key articles for additional studies and inclusion of relevant abstracts presented at key meetings.

The short-term outcomes of interest for this review included RSVH rates, hospital length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) admission and LOS, oxygen requirement, need for and duration of mechanical ventilation and/or non-invasive ventilation, case-fatality rates, and risk factors (including biological, environmental and social) for severe RSV infection requiring hospital admission.

Evaluation of Data

Included publications were graded according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence [26, 27] (Supplementary Material 1—REGAL Protocol). For each study, we conducted a risk of bias assessment using the RTI Item Bank (score of 1 = very high risk of bias; score of 12 = very low risk of bias) for observational studies [28]. No quantitative data synthesis was conducted due to heterogeneity between studies in terms of design, patient populations, RSV testing, recording and availability of outcomes, and differences in clinical practice between countries and over time.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously published studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Articles Selected

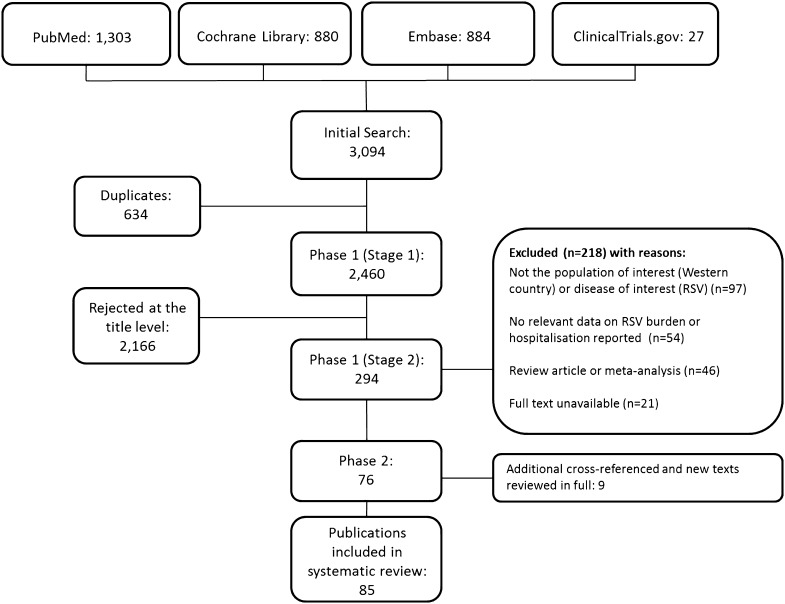

From a total of 2469 publications, 85 studies were included in the final review: 76 identified from the database searches and a further 9 from reference lists/other sources (Fig. 1). Data extraction tables for all 85 studies, including evidence grades and risk of bias assessments can be found in the online supplement (supplementary material 2).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram: epidemiology and burden of RSV hospitalization in infants born at <37 weeks’ gestational age without chronic lung disease (bronchopulmonary dysplasia) or congenital heart disease. RSV respiratory syncytial virus

Incidence of RSVH in Preterm Infants

Both prospective and retrospective population-based studies performed in the US, Canada and Europe have demonstrated that infants with a history of prematurity are at increased risk for RSVH [3–5, 29–46]. Preterm infants, particularly those born at lower gestational ages, tended to have higher rates of hospitalization for RSV compared to otherwise healthy term infants [4, 5, 31, 37, 43, 47–51]. In a 5-year prospective, population-based study, very preterm infants (<30 wGA) accounted for only 3% of RSV cases, but had RSVH rates three times that of term infants [4]. In the French CASTOR (Comparison of the rAte of hoSpitalization for RSV bronchiolitis between preterm infants born at 32 wGA or less without BPD and full-teRm infants) study, preterm infants had a fourfold increased risk of hospitalization for RSV bronchiolitis compared to the matched full term group (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.36–11.80) [50]. In the Dutch LOLLIPOP (Longitudinal Preterm Outcome Project) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: ISRCTN80622320) [43], the rates of RSVH were found to be higher in preterm infants 32–36 wGA than full term infants (3.9% vs. 1.2%, relative rate [RR]: 3.2; 95% CI: 1.4–7.1, P = 0.003), but similar to that among preterm infants <32 wGA (3.9% vs. 3.2%, RR: 1.2, 95% CI: 0.7–2.1, P = 0.50) and higher than that among full term infants. Overall, rates of RSVH tended to be around 3 times higher in premature than term infants, albeit with considerable heterogeneity across studies (range 1.1–8.1 times higher) [5, 31, 37, 43, 47–51]. In these studies, the majority of preterm infants were previously healthy, providing evidence that preterm infants without underlying conditions, such as CLD (BPD) and CHD, are at increased risk of developing severe RSV infection.

RSVH rates for preterm infants over the last two decades vary in the literature [4, 5, 8–12, 29, 31, 37, 47, 49, 51–57], ranging from ~5/1000 children [4] to >100/1000 children [52, 53], with the highest RSVH rates reported in the lowest gestational age infants (Table 1). In the majority of these studies, RSV immunoprophylaxis was not given. In the Dutch RISK [10] and RISK-II [11] studies, the overall RSVH risk for healthy preterm infants born at 33–35 wGA was 51/1000 children and 35/1000, respectively. In Austria, the overall RSVH risk for infants born at 29–32 wGA was 45/1000 children. RSV immunoprophylaxis was given to 29.7% infants, but almost half of these received inadequate or incomplete courses [56]. In the PICNIC study [9], the RSVH rate for infants born at 33–35 wGA was 36/1000 children, although center and seasonal variation in hospitalization rates for RSV infection were observed. A more recent study of 32–35 wGA infants followed prospectively from September to May 2009–2010 or 2010–2011 in the US [57], found that the observed hospitalization rate (49/1000 infant-seasons) was similar to that reported in other studies conducted outside the US that employed active surveillance for laboratory-confirmed RSV [9, 44]. In the PONI study [12], a multinational study (23 countries) of 33–35 wGA infants ≤6 months of age during the October 2013 to April 2014 RSV season, the RSVH rate was 61/1000 infant-years. Differences in reported RSVH rates could relate to variability in study methodology and changes in RSV testing and/or changes in the use of RSV-specific codes. These findings highlight the need for rigorous, uniform and ongoing data collection.

Table 1.

RSV hospitalization rates for premature infants without CLD (BPD) or CHD

| Study | Country | Design | Hospitalization rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36–37 wGA | 32–35/36 wGA | ≤33 wGA | <28 wGA | ≥38 wGA | |||

| Straňák 2016 [12] | Multinational (23 countries)t | 1-year multicenter prospective study (2013–2014); 2390 infants ≤6 months of age born at 33–35 wGA (excluded infants with BPD/CLD or hsCHD or who received/planned to receive RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 61.0a | – | – | – |

| Resch 2006 [56] | Austria | 2-year multicenter retrospective/prospective study (2001–2003); 863 children <2 years old born at 29–32 wGA (included some infants with BPD, CHD or neurological diseases; 29.7% received RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | – | 45.0c, d | – | – |

| Law 2004 [9] | Canada | 2-year multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study (2001–2002, 2002–2003); 1832 infants <1 year old born at 33–35 wGA; excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 36.0c, g | – | – | – |

| Haerskjold 2015 [48] | Denmark | 7-year retrospective, population-based cohort study (1997–2003); 6 national registries; children ≤2 years old (included 5200 [1.2%] infants 23–32 wGA, 11,193 [2.7%] infants 33–35 wGA, 9815 [2.3%] infants 36 wGA (excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | 22.6b, k | 28.0b, g | 50.8b, l | – |

14.1b, i 11.5b, n |

| Gouyon 2013 [50] | France | 1-year retrospective/prospective study (2008–2009); 9 regional networks; 498 infants <6 months old (249 preterm infants <33 wGA without BPD, CHD or immunodeficiency; 249 matched full term infants; excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | – | 64.0c | – | 16.0c |

| Doering 2006 [55] | Germany/Austriao | 2-year retrospective study (1998–1999; 2001–2002); 1158 infants <1 year old born at 29–35 wGA (included some infants with CLD, CHD or neurological diseases; excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 42.0c, d | – | – | – |

| Pezzotti 2009 [59] | Italy | 6-year retrospective, longitudinal study (2000–2006); 2 local health units; 2407 children <3 years old born at <36 wGA (201 [8.3%] born <29 wGA (included some infants with BPD or CHD; 13.5% received RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 46.0a, j | – | – | – |

| Korsten 2016 [11] | Netherlands | 4-year prospective study (2011–2015); 41 hospitals; 4088 healthy infants ≤1 year old born at 33–35 wGA (excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis)s | – | 35.0c | – | – | – |

| Gijtenbeek 2015 [43] | Netherlands | Retrospective study of children born 2002–2003; community-based cohort; 524 children born <32 wGA, 964 children born 32–36 wGA, 572 born 38–42 wGA | – | 39.0c | – | 32.0 c | 12.0c |

| Blanken 2013 [10] | Netherlands | 2-year prospective study (2008–2011)p; 41 hospitals; 2421 healthy preterm infants ≤1 year old born at 33–35 wGA (excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 51.0c, g | – | – | – |

| Fjaerli 2004 [24] | Norway | 8-year, retrospective, population-based study (1993–2000); single center/region; 764 children ≤2 years old (included 58 [7.6%] infants <37 wGA; majority previously healthy) |

<1 year:f 23.5c 1–2 years:f 8.7c ≤2 years:f 16.2c |

– | – | – | – |

| Figueras-Aloy 2008 [8] | Spain | 2-year prospective 2-cohort study (2005–2006, 2006–2007); 37 hospitals; 5441 preterm infants ≤1 year old born at 32–35 wGA (202 RSV + cases; some infants received RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 37.0c | – | – | – |

| Cilla 2006 [32] | Spain | 4-year retrospective study (1996–2000); single-center; 357 children <2 years old admitted with virologically-confirmed RSV infection (included 80 infants ≤37 wGA; majority previously healthy) | 29.4c | 78.1c | 44.2c | – | 19.1c |

| Carbonell-Estrany 2000 [52] and 2001 [53] | Spain | 2-year observational, prospective, longitudinal, multicenter study (1998–1999, 1999–2000); 14 neonatal units; preterm infants ≤32 wGA (584 in 2000 season and 999 in 2001 season) | – | – | 131.0–134.0c | – | – |

| Ericksson 2002 [47] | Sweden | 12-year retrospective study (1987–1998); single center/tertiary; 1503 children <2 years old (included infants <33 wGA without CLD) | – | – |

Early season: 16.0c Late season: 32.0c |

– |

Early season: 14.0c Late season: 8.0c |

| Deshpande 2003 [31] | UK | 3-year retrospective study (1996–1999); county; 561 children <2 years old hospitalized for bronchiolitis (53 preterm infants ≤36 wGA hospitalized with RSV) | – | 89.0c, m | – | 125.0c, m | 24.0–36.0c, j |

| Helfrich 2015 [49] | USA | Retrospective cohort study (2005–2011); military health system; 599,535 preterm infants ≤2 years old born at 33 + 0 through 36 + 6 wGA | – | 12.1a, g | – | – | 7.8a, g |

| Ambrose 2014 [57] | USA | 2-year prospective study (2009–2010 and 2010–2011); 188 US sites; 1642 infants <6 months old born at 32–25 wGA (excluded infants receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis) | – | 49.0a | – | – | – |

| Hall 2013 [4] | USA | 5-year prospective, population-based study (2000–2005); 2149 children <2 years old (10% <37 wGAe; included children with comorbid conditions; 23% RSV + preterms received RSV immunoprophylaxis) | 4.6c,f | – | – | 18.7c, h | – |

| Hampp 2011 [51] | USA | 1 RSV season retrospective study (2004–2005); Florida Medicaid claims data; 159,790 infants (included infants ≤6 months born at ≤32 wGA and infants <2 years with CLD, CHD, or neither co-morbidity) | – | – | 42.1c, q | – | 12.5c, r |

| Boyce 2000 [5] | USA | 4-year retrospective cohort study (1989–1993); state; children <3 years old (included infants <36 wGA and infants with BPD, CHD); 248,652 child-years of follow-up | – |

0–6 months: 79.8c,g 6–12 months: 34.5c,g 1–2 years: 10.8c, g 2–3 years: 0.9c, g |

– |

0–6 months: 93.8c 6–12 months:46.1c 1–2 years: 30.0c 2–3 years:0.0c |

0–6 months: 44.1c 6–12 months: 15.0c 1–2 years: 3.7c 2–3 years: 1.0c |

| Summary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wGA | Number of studies | Number of countries | Population age range and timeframe of studies | Hospitalization rate |

| 36–37 | 4 | 4 | ≤2 years; 1993–2005 | 4.6–29.4c; 22.6b |

| 32–35/36 | 14 | 31 | <3 years; 1989–2015 | 0.9–89.0c; 28.0b; 12.1–46.0a; 49.0a |

| ≤33 | 7 | 6 | ≤2 years; 1987–2009 | 16.0–134.0c; 50.8b |

| <28 | 4 | 3 | <3 years; 1989–2005 | 0.0–125.0c |

| ≥38 | 9 | 7 | <3 years; 1989–2011 | 1.0–44.1c; 11.5–14.1b; 7.8a |

BPD bronchopulmonary dysplasia, hs hemodynamically significant, CHD congenital heart disease, CLD chronic lung disease, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, RSV (+) respiratory syncytial virus (positive), wGA weeks’ gestational age

aPer 1000 infant-years

bPer 1000 years of risk

cPer 1000 infants

dInfants 29–32 wGA or 29–35 wGA

eGestational age could not be verified for 24 RSV-positive children

fInfants <37 wGA

gInfants 33 to <36 wGA

hInfants <30 wGA

iInfants <37–41 wGA

jIncidence rate for first RSVH for children in first 18 months of life (<36 wGA without BPD or CLD)

kInfants 36 wGA

lInfants 23–32 wGA

mInfants ≤36 wGA and <6 months of age

nInfants 42–45 wGA

oCombined analysis of Liese [57] and Resch [56]

pIncluded 2 cohorts, one of infants born 2008–2009, other of infants born 2009–2011

qInfants ≤32 wGA, incidence rate adjusted to compensate for RSV prophylaxis

rInfants without CLD, CHD or prematurity, incidence rate adjusted to compensate for RSV prophylaxis

sFollow-up of Blanken [10]

tWestern Europe (Austria, France, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland), Eastern Europe (Bosnia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) and Russia, South Korea, Mexico, and the Middle East (Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, and Saudi Arabia)

Chronological age appears to have a strong effect on RSVH risk in preterm infants [58]. A retrospective cohort study reported that the risk of RSVH for a preterm infant born 32–34 wGA was the same at 4.2–4.5 months of age as for a term infant at 1 month of age [58]. In a prospective, population-based study of RSVH in premature and term infants by Hall et al. [4], infants ≤2 months accounted for an important proportion of all children admitted with RSV infection in the first 2 years of life: 11% were infants <1 month old, 44% were ≤2 months old, and only 36% were >5 months old. In a retrospective longitudinal study of 2407 preterm infants in Italy, the incidence of RSVH declined with age [59]. In this study, significantly higher incidence rates were observed in the first 6 months of life and incidence rates significantly decreased with age (P < 0.01), from 89.3/1000 person-years for infants aged 0–6 months to 7.6/1000 person-years for infants aged 12–18 months. Incidence rates also varied significantly by month of age (P < 0.01) and by calendar month (P < 0.01). After 18 months of age, however, RSVH was rare [59]. A recent retrospective analysis from the Osservatorio Study in Italy [60], which enrolled three different gestational age group infants (<29, 29 to <32 and 32–35 wGA), found that the percentage of hospitalized preterm infants ≤12 months old that were RSV positive progressively decreased from 40.0% to 28.6% and 18.4% with increasing wGA (P = 0.43). These data suggest that, at least in the first year of life, the most premature infants were more vulnerable and prone to RSV infection [60].

Further data from a post hoc analysis of the Spanish FLIP 2 study [8] indicate that the risk of RSV-related hospitalization is maintained in many preterm infants born at 32–35 wGA up to at least 6 months old and baseline risk factors continue to contribute varying risk over the infants first year of life [61]. These findings may have implications for future prevention strategies and the authors suggest that further prospective studies be undertaken to fully explore the changing risk of RSVH during the first year of life in preterm infants [61].

RSVH Rates by Gestational Age

There is also variability in reported RSVH rates among different gestational groups, as evidenced by the results of a large, population-based Danish study of children followed from birth to 2 years of age [48]. In this study, incidence rates of hospitalization for RSV infection were calculated for five groups of children separated by gestational age (23–32, 33–35, 36, 37–41, and 42–45 wGA). The highest hospitalization rates for RSV infection were found in the group of very preterm children born 23–32 wGA (50.8/1000 years of risk) [48]. Hall et al. [4] also observed significantly higher RSVH rates for <30 wGA infants (18.7/1000 children) compared with both 30–33 wGA infants (2.7/1000 infants) and 34–36 wGA (5.8/1000 infants). The authors suggest these variances may primarily result from premature infants in certain gestational age ranges being too few to reliably calculate hospitalization rates by gestational weeks. In addition, care patterns and environmental risks may be different for late preterm infants [4]. In contrast, Cilla et al. [37] found that the highest RSVH rates in the first year of life were in infants with a gestational age of 33–35 weeks (78.1 cases/1000 infants).

Rehospitalization Rates for RSV Infection Following Discharge from Neonatal ICUs

The reported risk of RSVH for preterm infants without CLD (BPD) or CHD following discharge from neonatal ICUs (NICU) ranges from 1.8% to 11.1%, depending on gestational age [62, 63]. In the study by Joffe et al. [63], three factors independently increased the risk of rehospitalization for RSV among preterm infants who were discharged from the NICU: <32 wGA, a perinatal oxygen requirement of ≥28 days, and discharge from the NICU during the 3 months before the RSV season. In an earlier study by Carbonell-Estrany et al. [53], rehospitalization for a second RSV infection for a single infant in the same season was observed during both RSV seasons (11% [1999] and 8% [2000] of all admissions for RSV illness, respectively).

Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Severe RSV Infection

Morbidity

Results from a number of studies show that preterm infants are at an increased risk for morbidity and increased rates of health care resource utilization, including longer duration of illness and longer hospital stays, compared with full-term infants [5, 8, 14, 16, 29, 46, 50, 57, 64–72]. Data also show that nosocomial RSV infection in high-risk infants, including preterm infants, often follows a severe course of disease [73].

Children with a history of prematurity are at a higher risk of worse hospital outcomes (use of supplemental oxygen, NICU admission) for RSV infection than term infants [5, 8, 12, 14, 24, 46, 49, 50, 57, 58, 64–72, 74, 75]. In the French CASTOR study, preterm infants <33 wGA were prone to more severe disease as suggested by longer hospital stays and the requirement of more therapeutic care, including oxygen therapy and non-mechanical ventilation, compared with the full-term group [50]. Similarly, a retrospective study conducted in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) reported that, among RSV-positive patients, premature children (<37 wGA) had a significantly longer hospital stay (17 vs. 8 days; P < 0.001), were more frequently hospitalized in the ICU (41.4% vs. 12.6%), and remained in the ICU significantly longer (13 vs. 6 days; P < 0.001) compared with term children [46]. In a Canadian study, Sampalis [64] analyzed data from 2415 preterm infants (32–35 wGA) without BPD hospitalized for proven or probable RSV matched (by GA, gender, and province of birth) to 20,254 control infants without RSVH. During hospitalizations after the index admission, the RSV cohort had a significantly higher mean number of visits to special care units (0.67 vs. 0.40, respectively; P < 0.001), use of respiratory therapy (0.31 vs. 0.13, respectively; P < 0.001), physician consults (3.61 vs. 0.89, respectively; P < 0.001), and therapeutic or diagnostic procedures (1.05 vs. 0.81, respectively; P < 0.001) compared with matched control infants. Similar findings were reported in the United Kingdom (UK) [16]. Shefali-Patel et al. [16] observed that healthcare utilization was significantly greater in the RSV compared to the non-respiratory group for respiratory outpatient visits (6.1 vs. 3.8), hospital admissions (2.3 vs. 0.3; P < 0.001), respiratory-related hospital admission (1.3 vs. 0; P < 0.001), duration of hospital admission (9.6 vs. 0.4 days; P < 0.001), pediatric ICU (PICU) admission (1.6 vs. 0 days; P < 0.001), respiratory primary care visits (12.4 vs. 9.4; P = 0.07), emergency department visits (3.0 vs. 0.7; P < 0.001), and respiratory emergency department visits (1.6 vs. 0.1; P < 0.001). Data from a Finnish study also showed that infants aged <6 months with bronchiolitis were most likely to need major medical interventions (supplementary oxygen, intravenous fluids, intravenous antibiotics or admission to the ICU) in the first 5 days after disease onset [76].

In contrast to other studies, while admission to the ICU was associated with a history of premature birth (odds ratio [OR]: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.1–2.4, P = 0.01), Sala et al. [77] found no significant difference in the ICU LOS (106 [42–252] days vs. 106 [59–219] days; P = 0.94) or in mechanical ventilation (OR: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.6–2.1; P = 0.8) between infants with and without a history of prematurity. Similarly, Gijtenbeek et al. [43] found no relation between gestational age and disease severity or in hospitalization LOS or use of mechanical ventilation and oxygen.

Further data on hospital resource utilization for RSV infection in preterm infants without CLD born at 32–35 wGA and not receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis come from the REPORT (RSV Respiratory Events Among Preterm Infants Outcomes and Risk Tracking) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00983606) [57]. Among the 57 preterm infants with confirmed hospitalization, the median duration of hospital stay was 4 days (range 2–18 days); 9 (16%) were admitted to the ICU and 11% required mechanical ventilation. The proportion that required ICU admission was similar among infants born at 32–34 wGA (4 of 21) and 35 wGA (5 of 36) [57]. Additional data from the REPORT study regarding ICU admissions suggest that young age is the most important risk factor associated with the incidence of ICU admission among 32–35 wGA infants hospitalized for RSV [78]. Among 32–35 wGA infants hospitalized with RSV and <3 months actual age in weeks since birth, the proportion admitted to the ICU was 27% (6/22), and the ICU admission rate was 1.8 per 100 infant-seasons. The highest incidence occurred at 2 to <3 months actual age. Among those 3 to <6 months actual age, the proportion admitted to the ICU was 14% (3/22), yielding a rate of 7 per 1000 infant-seasons. No ICU admissions occurred in those ≥6 months [78].

Hospital LOS and healthcare utilization, including admission to ICU, for preterm infants <37 wGA are shown in Table 2. This population at high risk for severe RSV infection spend a median of 2–17 days in hospital for RSV-related illness [14, 16, 24, 31, 50, 57, 79, 80], and up to 75% are admitted to the ICU, depending on gestational age [12, 14, 16, 46, 50, 57, 72, 74].

Table 2.

Length of hospital stay, ICU admission and mechanical ventilation for preterm infants hospitalized with severe RSV infection

| Study | Country | Study participants | Hospital LOS, median days (range) | ICU admission (%) | ICU LOS, median days (range) | Oxygen therapy (%) | Mechanical ventilation (%) | Non-invasive ventilation (%) | Case-fatality rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Straňák 2016 [12] | Multinational (23 countries)l | 1-year prospective (2013–2014); multicenter; 2390 infants ≤6 months old born at 33–35 wGA (infants with BPD/CLD or CHD or who received or were planned to receive RSV immunoprophylaxis were excluded) | NR | 29.7 | 6 (5–12) | 73.4 | 10.9 | NR | NR |

| Van de Steen 2016 [46] | Central and Eastern Europe (12 countries)m | 2-year retrospective (2009–2011); multicenter; 266 infants <1 year old born at <37 wGA (34.2% with co-morbidities) hospitalized with confirmed RSV bronchiolitis | 17 (20)e | 41.4 | 13 (15)e | 72.9 | NR | NR | 2.6 |

| Gouyon 2013 [50] | France | 1-year retrospective/prospective (2008–2009); 498 infants <6 months old (249 preterm [<33 wGA] without BPD and 249 matched term infants) hospitalized with bronchiolitis (RSV-confirmed and all types) | 5 (2–13)c | 5.9 | NR | 54.5c | NR | 15.2c | NR |

| Tsolia 2003 [72] | Greece | 4-year retrospective/prospective (1997–2000); 636 infants <1 year old admitted with bronchiolitis (61% had confirmed RSV and 12% of these were preterm infants ≤36 wGA) | NR | 26 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5.7 |

| Bala 2005 [80] | Ireland | 5-year retrospective (1997–2001); 174 preterm infants (<32 wGA) hospitalized with bronchiolitis | 5 | 0 | NA | NR | NR | NR | 0 |

| Fjaerli 2004 [24] | Norway | 8-year retrospective, (1993–2000); 764 children <2 years old (7.6% preterm [<37 wGA], some with additional comorbidities) hospitalized with RSV bronchiolitis | 8 (2–7) | NR | NR | NR | 3.4% | NR | 0 |

| Figueras-Aloy 2008 [8] | Spain | 2-year prospective (2005–2006, 2006–2007); 37 hospitals; 5441 preterm infants born at 32–35 wGA (202 RSV + cases; some infants received RSV immunoprophylaxis) | 7 (4–10)i | 17.8 | 5 (3–10.8)i | NR | 7.4 | NR | 0 |

| Shefali-Patel 2012 [16] | UK | 8-year retrospective (2000–2007); 158 children <2 years old born at 32–35 wGA with respiratory and non-respiratory admissions (20 with RSV infection) | 4.5 (1–110) | 75 | 0 (0–29) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Deshpande 2003 [31] | UK | 3-year retrospective study (1996–1999); 561 children <2 years old with bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations (53 preterm infants ≤36 wGA hospitalized for RSV) | 2 (1–4)d | NR | NR |

≥28 days: 9.5f <28 days: 6.6f |

12.6f | NR | NR |

| Anderson 2016 [74] | USA | 1-year retrospective/prospective (2014–2015); 709 infants <1 year old born at 29–35 wGA hospitalized with RSV |

Overall: 5 (1–135)j 29–32 wGA: 6 (1–67)j 33–34 wGA: 6 (1–101)j 35 wGA: 5 (1–135)j |

Overall: 42j 29–32 wGA: 49j 33–34 wGA: 43j 35 wGA: 31j |

Overall: 6 (1–91)j 29–32 wGA: 8 (1–61)j 33–34 wGA: 6 (1–91)j 35 wGA: 5 (1–59)j |

NR |

Overall: 20j 29–32 wGA: 24j 33–34 wGA: 20j 35 wGA: 13j |

NR | 0.1h |

| Ambrose 2014 [57] | USA | 2-year prospective (2009–2010 and 2010–2011); 1642 preterm infants (32–35 wGA) <6 months old | 4 (2–18) | 16 | NR | NR | 11 | NR | NR |

| Underwood 2007 [79] | USA | 9-year retrospective (1992–2000); 263,883 premature infants (<36 wGA) readmitted to hospital (1.6% hospitalized for RSV) | 5.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Horn 2003 [14]k | USA | 17-month retrospective (1995–1996); 304 infants ≤1 year old (89 < 37 wGA)n |

≤32 wGA: 6.8e 33–35 wGA: 8.4e 36 wGA: 4.9e |

≤32 wGA: 39.3 33–35 wGA: 48.4 36 wGA: 30 |

≤32 wGA: 5.8e 33–35 wGA: 7.7e 36 wGA: 4.2e |

NR |

≤32 wGA: 21.4 33–35 wGA: 38.7 36 wGA: 20 |

NR | 0 |

| Willson 2003 [75]k | USA | 17-month retrospective (1995–1996); 684 infants ≤1 year old hospitalized for bronchiolitis or RSV pneumonia (12.7% preterm infants ≤35 wGA)n |

≤32 wGA: 4.0 33–35 wGA: 5.0 36 wGA: 3.5 ≥37 wGA: 3.0 |

NR |

≤32 wGA: 3.9 33–35 wGA: 5.0 36 wGA: 4.5 ≥37 wGA: 2.5 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Care 2016 [81] | Turkey | 1 RSV season (2013–2014); 250 infants hospitalized for RSV (median age 23 [4–153] days); 79 preterm infants ≤36 wGA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2.5 |

| Summary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Number of studies | Number of countries | Population age range and timeframe of studies | Value |

| Hospital LOS | 12 | 18 | <2 years; 1992–2015 | 2–17a |

| ICU admission | 10 | 33 | <2 years; 1995–2015 | 0–75b |

| ICU LOS | 7 | 32 | <2 years; 1995–2015 | 0–6a |

| Oxygen therapy | 4 | 30 | <2 years; 1996–2014 | 54.5–73.4b; ≥28 days: 9.5b, <28 days: 6.6b |

| Mechanical ventilation | 7 | 26 | <2 years; 1993–2015 | 3.4–38.7b |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 1 | 1 | <6 months; 2008–2009 | 15.2b |

| Case-fatality rate | 8 | 18 | <2 years; 1993–2015 | 0–5.7b |

ICU intensive care unit, LOS length of stay, NR not recorded, wGA weeks’ gestational age, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, BPD bronchopulmonary dysplasia, CLD chronic lung disease

aMedian days

b%

cPreterm infants tested for RSV

d53 preterm infants with RSVH for whom complete neonatal data were available

eMean (standard deviation)

fData for preterm infants ≤36 wGA under 6 months of age at the onset of each RSV season (1996–1999)

hOne death recorded in 29 wGA infant with community-acquired RSV and no reported comorbidities

iInterquartile range

j702 patients with community-acquired RSV infection (excludes 7 patients with nosocomial RSV infection)

kData for both studies come from one larger study

lWestern Europe (Austria, France, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland), Eastern Europe (Bosnia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) and Russia, South Korea, Mexico, and the Middle East (Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, and Saudi Arabia)

mEstonia, Lithuania, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia/Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania, and Ukraine

nHorn [14] and Willson [75] used different subsets of the same baseline dataset

In addition to the acute burden placed on pediatric services during the winter season, RSVH has been associated with on-going respiratory morbidity. This will be covered in a subsequent publication in the REGAL series.

Gestational Age-Specific Complications and Hospital Resource Use

Severe RSV infection in preterm infants <37 wGA has been shown to result in substantial morbidity associated with hospitalization, but few studies have characterized RSV-confirmed hospitalizations in this high-risk population.

Consistent with previous studies [5, 14, 49, 57, 58, 65], recently published data from the ongoing SENTINEL1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02273882) [74, 81] demonstrated that earlier gestational age and younger chronologic age were associated with a higher risk of ICU admission and need for mechanical ventilation compared with birth at later gestational age and older chronologic age (Table 3). In this study, data on infants born at 29–35 wGA not receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis were collected from 43 sites across the US [74]. In total, 702 infants were hospitalized for community-acquired RSV infection and overall, 42% were admitted to the ICU and 20% required mechanical ventilation [74, 81]. Infants <6 months of age accounted for 78% of RSVH observed, 87% of ICU admissions, and 92% of those requiring mechanical ventilation [74]. Adjusting for their prevalence in US births, the number of RSVH among infants 29–32 and 33–34 wGA were 2-fold (95% CI: 1.6, 2.4) and 1.5-fold (95% CI: 1.2, 1.8) higher, respectively, than that of infants 35 wGA. The number of ICU admissions among infants 29–32 and 33–34 wGA were 3.1-fold (95% CI: 2.2, 4.2) and 1.9-fold (95% CI: 1.4, 2.6) higher, respectively, than that of infants 35 wGA [81]. The number of mechanical ventilation events among infants 29–32 and 33–34 wGA were 3.4-fold (95% CI: 2.2, 5.3) and 1.9-fold (95% CI: 1.2, 3.1) higher, respectively, than that of infants 35 wGA [81]. The SENTINEL1 study also reported on the costs of RSVH, which were substantially higher for those who required greater intensity of care, as reflected by ICU admission and need for mechanical ventilation, regardless of wGA and chronological age [74]. The overall, median cost per RSVH was $27,461 US dollars [74].

Table 3.

Characteristics of community-acquired, respiratory syncytial virus-confirmed hospitalizations in the SENTINEL1 study [74]

| Variable | wGA | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29–32 (n = 237) | 33–34 (n = 283) | 35 (n = 182) | 29–32 vs. 33–34 wGA | 29–32 vs. 35 wGA | 33–34 vs. 35 wGA | |

| Age at admission, monthsa | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS, daysa | 6 (3–12) | 6 (3–10) | 5 (3–7) | NS | 0.001 | <0.05 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 115 (49) | 117 (43) | 56 (31) | NS | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| ICU LOS, daysa | 8 (3–14) | 6 (3–12) | 5 (3–9) | NS | NS | NS |

| Mechanical ventilation among all admissions, n (%) | 58 (24) | 53 (20) | 23 (13) | NS | <0.01 | NS |

ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, LOS length of stay, wGA weeks’ gestational age

aValues reported as median (IQR)

Increasing severity of disease with decreasing gestational age was also seen in the retrospective study from CEE [46]. Duration of hospitalization (mean days, ≤28 wGA: 29; 29–32 wGA: 24; 33–36 wGA: 11; term: 9), ICU hospitalization (≤28 wGA: 54.3%; 29–32 wGA: 48.8%; 33–36 wGA: 33.8%; term: 14.1%), LOS in ICU (mean days, ≤28 wGA: 19; 29–32 wGA: 17; 33–36 wGA: 7; term: 7), supplemental oxygen use (≤28 wGA: 80.0%; 29–32 wGA: 77.9%; 33–36 wGA: 68.3%; term: 47.6%), and duration of supplementary oxygen use (mean days, ≤28 wGA: 19; 29–32 wGA: 12; 33–36 wGA: 5; term: 5) all significantly differed across gestational age groups (all P < 0.001) [46]. Additional data come from a retrospective cohort study of 684 infants (12.7% preterm infants ≤35 wGA) aged ≤1 year hospitalized for bronchiolitis or RSV pneumonia over an 18-month period [75]. Preterm infants born at 33–35 wGA had the highest rates of complications (93%), longest hospital LOS (7.4 days), and highest costs ($14,137) of all the gestational groups studied [75].

In addition to the associated morbidity, RSVH costs for preterm infants have been shown to be substantial at follow up [16–18, 82–84]. In a retrospective cohort study undertaken in the US, preterm infants born at 33–36 wGA with a RSVH incurred $21,977 higher costs (P < 0.001) compared with corresponding controls without RSVH during their first year of life [82]. In another retrospective study in the UK, RSVH was associated with a significant increase in the health-related cost of care in the first 2 years after birth in infants born between 32 and 35 wGA. The mean cost of care in the RSV group (£12,505) was greater than the non-respiratory (£1178) (95% CI for difference £5015 to £17,639, P < 0.002) and the other respiratory (£3356) groups (95% CI for difference £2963 to £15,606, P < 0.001) [16]. It has been calculated that over the first year of life, 33–36 wGA and <33 wGA infants hospitalized with RSV go on to incur healthcare costs almost five times and three times higher, respectively, than preterm infants with no history of RSV infection [85]. In a further study undertaken in the Netherlands, estimated mean hospitalization costs for RSV were highest for patients with lower gestational age (€5555, ≤28 wGA) as a result of a longer duration of hospitalization [83]. These findings highlight the importance of preventive strategies in this high-risk group.

Case-Fatality Rates

Severe RSV infection is an important cause of childhood mortality worldwide [1]. However, few studies in the published literature on RSVH report case-fatality rates in preterm infants and therefore it is difficult to ascertain from the available data the precise number of true RSV deaths in this high-risk population. Two studies undertaken in the US [86] and Canada [64] in the early 2000s reported that RSVH in healthy premature infants is associated with increased mortality. Leader et al. [86] found that low birth weight and/or prematurity (≤35 wGA) independently increased the risk of post-neonatal RSV-associated death in children. Case-fatality rates were 43/100,000 for infants without comorbidities born at ≤35 wGA and weighing <2500 g compared with 20.3/100,000 for infants without comorbidities born at ≥37 wGA and weighing <2500 g (total number of deaths recorded in infants without comorbidities: 288) [86]. Sampalis [64] evaluated morbidity and mortality in healthy preterm infants (32–25 wGA) and matched controls and reported an overall mortality rate during the follow-up period of 8.1% (196/2415) in the RSV cohort and 1.6% (320/20,254) in the control infants (OR: 5.5; 95% CI: 4.6–6.6, P = 0.001). The author concluded that RSVH in healthy premature infants was associated with a significant increase in subsequent health care resource utilization and mortality. More data are needed on cause of death and how much is directly attributable to RSV [64].

RSVH and Health-Related Quality of Life

RSV-related hospitalization may cause significant distress for infants and children [87], as well as caregivers and families [87, 88]. Leidy et al. [87] performed a prospective study in 46 RSV-hospitalized infants and children aged ≤30 months with a history of prematurity (≤35 wGA) and 45 age-matched control subjects without RSVH. During hospitalization, the RSV-infected patients’ health and functional status were significantly poorer than those of control subjects. Caregivers of RSV-infected children reported more stress, greater anxiety, poorer health, and poorer family health and functioning. As long as 60 days after hospital discharge, caregivers of RSV-infected children reported the children’s health as significantly poorer and they were personally more anxious, compared with control subjects [87]. In the Spanish FLIP-2 study [88], parents of hospitalized preterm infants of 32–35 wGA were most likely to have more and longer times off work for child care (47% vs. 18%), to have higher work overload, and to obtain lower values in health-related, quality-of-life measures.

Independent Gestational Age-Specific Risk Factors for RSVH

Several important independent risk factors for RSVH have been identified in preterm infants who had not received RSV immunoprophylaxis [48, 50, 52, 53, 55].

23–32 wGA Few studies on risk factors for RSVH have been performed in extremely preterm infants. In the study by Haerskjold et al. [48], the associations between potential risk factors for hospitalization for RSV infection were analyzed using a Cox regression model. Asthma hospitalization before RSV infection and siblings was associated with increased risk of hospitalization for RSV infection in children born between 23 and 32 wGA [48].

29–35 wGA Doering et al. [55] evaluated risk factors for RSVH in a large German-Austrian cohort of preterm children with a gestational age of 29–35 weeks. In multivariate analyses, four independent risk factors for RSVH were identified: neurologic problems (OR 3.6); male sex (OR 2.8); presence of an older sibling (OR 1.7); and discharge from October to December (OR 1.7). Based on this multivariate analysis, the estimated risk of RSVH varied between 1% (no risk factor present) and 30% (4 risk factors present).

Other studies have analyzed risk factors for RSVH in infants born at 29–35 wGA [48, 50, 52, 53]. In two studies undertaken in Spain, significant independent prognostic variables for high risk of RSVH in this gestational group of infants included: lower gestational age (OR 1.85); chronologic age <3 months at onset of the RSV season (OR 1.44); CLD (OR 3.1); living with school age siblings (OR 1.86); and exposure to tobacco smoke [52, 53]. In the study by Haerskjold et al. [48], in the adjusted Cox regression model chronic disease, asthma hospitalization before RSV infection, siblings, smoking and day care were all associated with increased risk of RSVH in infants born at 33–35 wGA. Similar to other studies, male gender and the presence of siblings aged ≥2 years were independent risk factors for multiple bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the French CASTOR study, which evaluated preterm infants born at <33 wGA without BPD [50].

Breastfeeding, on the other hand, has been found to have a protective effect [89]. In a prospective cohort study of 1814 infants born at ≤33 wGA, at 12 months of age, the risk of hospitalization for bronchiolitis was significantly higher in the ‘never breastfed’ group compared with the ‘breastfed’ group (hazard ratio: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.00–2.48) [89]. However, data about the specific protective effect of breastfeeding on RSV in 32/33–35 wGA infants are conflicting [7–9].

32–35 wGA Six large studies have investigated risk factors in infants born 32/33–35 wGA: the Spanish FLIP [7] and FLIP 2 [8] studies; the Canadian PICNIC [9] study; the Dutch RISK [10] and RISK-II [11] studies; and the multinational PONI study [12]. Independent risk factors for RSVH reported in these studies cover exposure (proximity of birth to the RSV season, living with school-age siblings, crowding at home, day care attendance), social factors (mother smoking during pregnancy, smoking around infants, reduced breast feeding), biological factors (small for gestational age, male sex, familial wheezing and atopy, young maternal age, low maternal education), and medical factors (neonatal respiratory support, short hospital stay at birth) (Table 4) [7–12]. In addition, a further analysis using data from several datasets, including the FLIP study [7] and the FLIP-2 study [8] showed that preterm infants born at 32–35 wGA from smoking families appear to be at heightened risk for severe RSV infection requiring hospitalization [90]. In this study, there were 2.35 times (95% CI 1.37–4.02) as many hospitalizations amongst infants from smoking compared with those from non-smoking families [90].

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with RSVH in the first year of life for infants born at 32/33–35 wGA

| Risk factors | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLIP study [7] (n = 557) | FLIP-2 study [8] (n = 5441) | PICNIC study [9] (n = 1758) | RISK study [10] (n = 2421) | RISK-II study [11] (n = 1564) | PONI study [12] (n = 2390) | |

| Exposure | ||||||

| Age at start of RSV season (a≤10 weeks, bbirth November-January, cbirth August 14th to December 1st, ≤3 monthsd) |

3.95a (2.65–5.90) P ≤ 0.001 |

2.99a (2.23–4.01) P ≤ 0.001 |

4.88b (2.57–9.29) P < 0.001 |

2.6c (1.6–4.2) P < 0.001 |

2.4c (1.8–3.2) P < 0.001 |

2.10d P = 0.0422 |

| Siblings (aschool age, bschool-age siblings or day care attendance, cpre-school-age, dsiblings or day care attendance, echildren aged 4–5 years) |

2.85a (1.88–4.33) P ≤ 0.001 |

2.04b (1.53–2.74) P ≤ 0.001 |

2.76c (1.51–5.03) P = 0.001 |

4.7d (1.7–13.1) P = 0.003 |

5.3d (2.8–10.10) P < 0.001 |

2.28e P = 0.0038 |

| Crowding at home (≥4a without subject and school age siblings, >5b counting subject) |

1.91a (1.19–3.07) P = 0.0074 |

– |

1.69b (0.93–3.10) P = 0.088 |

– | – | – |

| Day care attendance | – | – |

12.32 (2.56–59.34) P = 0.002 |

– | – | – |

| Social factors | ||||||

| Exposure to ≥2 smokersa, smoking of familyb | – | – |

1.71a (0.97–3.00) P = 0.064 |

– | – |

3.18 P < 0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | – |

1.61 (1.16–2.25) P = 0.0044 |

– | – | – | – |

| Breast feeding ≤2 monthsa |

3.26a (1.96–5.42) P ≤ 0.001 |

– | – |

1.7a (1.0–2.7) P = 0.04 |

1.6b (1.2–2.2) P = 0.003 |

– |

| Biological factors | ||||||

| Small for gestational age (<10th percentile) | – | – |

2.19 (1.14–4.22) P = 0.019 |

– | – | – |

| Male sex | – | – |

1.91 (1.10–3.31) P = 0.02 |

– | – | – |

| Family history of wheezing |

1.90 (1.19–3.01) P = 0.0068 |

– | – | – | – | – |

| Family history of eczemaa/atopyb in first degree relative, maternal atopic constitutionc, paternal atopyd | – | – |

0.42a (0.18–0.996) P = 0.049 |

1.9b (1.1–3.2) P = 0.01 |

1.5c (1.1–2.1) P = 0.01 |

3.28d P < 0.0001 |

| Non-hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease diagnosis | – | – | – | – | – |

4.09 P = 0.0077 |

| Maternal age ≤25 years | – | – | – | – | – |

2.72 P = 0.0009 |

| Low maternal education | – | – | – | – | – |

1.79 P = 0.0426 |

| Medical factors | ||||||

| Neonatal respiratory support | – | – | – | – |

2.2 (1.6–3.0) P < 0.001 |

– |

| Hospital stay <7 days (at birth) | – | – | – | – | – |

2.14 P = 0.0113 |

Maternal atopic constitution = maternal hay fever, asthma or eczema; Neonatal respiratory support = oxygen/nasal mask/CPAP and/or mechanical ventilation

RSV(H) respiratory syncytial virus (hospitalization)

Several predictive models have been developed from these six studies, using between 4 and 7 risk factors, to predict those premature infants at highest risk of RSVH [10–12, 91–93] (Table 5). The areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves ranged from 0.687 to 0.791 for the six models [10–12, 91–93], representing fair to good predictive accuracy (0.50–0.75 = fair, 0.75–0.92 = good, 0.92–0.97 = very good, and 0.97–1.00 = excellent) [94]. All the models except the ones derived from the PONI dataset [12] have been externally validated [10, 11, 92, 95–97]. In three of the six models (FLIP [7], FLIP 2 [8] and PICNIC [10]), age at the start of the RSV season was the most predictive variable. In the RISK and RISK-II models [10, 11], the presence of siblings or the subject attending day care was the most predictive variable (age was the second most predictive). A prospective evaluation of the PICNIC model found it reduced hospitalization in infants most ‘at-risk’ while avoiding RSV immunoprophylaxis in a large segment (81.9%) of 33–35 wGA infants considered at low risk for RSV infection [98].

Table 5.

Comparison of predictive models for respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in infants born 32/33–35 wGA

| FLIP [91] | FLIP 2 [93] | PICNIC [92] | RISK [10] | RISK-II [11] | PONI [12] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors |

7 Birth ± 10 weeks of season start Birth weight Breast feeding ≤2 months Number of siblings ≥2 years Number of family members with atopy Number of family members with wheeze Sex |

4 Birth ± 10 weeks of season start School-age siblings or day care attendance Mother smoking during pregnancy Sex |

7 Small (<10th percentile) GA Sex Born during RSV season (Nov–Jan) Family history without eczema Subject or siblings attending day care >5 individuals in the home, including the subject >1 smoker in the household |

4 Born Aug 14th to Dec 1st Presence of siblings or subject day care attendance Breast fed ≤2 months or not Atopy in 1st degree family member |

5 Birth between Aug 14th and Dec 1st Day care attendance and/or siblings Neonatal respiratory support Breastfeeding ≤4 months Maternal atopic constitution |

6 Age on 1st October ≤3 months Smoking of family members Age of mother at delivery ≤25 years Children 4–5 years old present Smoking of mother during pregnancy Subject day care attendance |

| Sensitivity/specificity | 0.72/0.71 | 0.062/0.99 | 0.68/0.72 | 0.46/0.79 |

Low risk (1% hospitalization): 0.90/0.35 High risk (13% hospitalization): 0.32/0.90 |

NR |

| ROC AUCa | 0.791 | 0.687 | 0.762 | 0.703 | 0.72 | 0.755 |

GA gestational age, NR not reported, ROC AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

aROC curves are constructed by plotting the sensitivity (true positives; number of RSV hospitalized infants predicted to be hospitalized) against the specificity (false positives; number of non-hospitalized infants predicted to be RSV hospitalized), with areas closer to one representing better predictive accuracy

Further data on risk factors in this specific gestational-age group come from the REPORT study [57]. Consistent with previous observations in the RISK study [10], overall RSV disease risk in infants 32–34 and 35 wGA who were <6 months of age during November to March and not receiving RSV immunoprophylaxis was elevated by day care attendance and preschool-aged, non-multiple-birth siblings (8.9 and 9.3 per 100 infant-seasons, respectively, vs. 3.5 for all other infants, P < 0.001). Chronologic or postnatal age <3 months was associated with a higher RSVH rate for infants 35 wGA but not for infants 32–34 wGA [57].

32–36 wGA Two further studies have assessed risk factors for RSVH in 32–36 wGA infants [43, 99]. In a recent prospective, observational study of 1825 infants in Ireland who had not received RSV immunoprophylaxis, 5 independent risk factors for RSVH were identified [99]. Neonatal respiratory morbidity (OR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.28–3.94) or being Caucasian (OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.04–5.29) were population-specific independent risk factors for RSVH, whereas the other identified independent risk factors confirmed those established in previous studies: older siblings (OR: 3.8; 95% CI: 1.97–7.41), birth July 15 to December 15 (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.09–3.92) and family history of asthma (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.01–3.39) [99]. In a retrospective study in the Netherlands, shorter gestational age and passive smoking independently increased the risk for RSVH among children born at 32–36 wGA, in multivariable analyses [43].

Conclusions

The impact of severe RSV infection in high-risk groups is important in planning preventive strategies. Findings of this review confirm that the risk for severe RSV disease is significantly increased in preterm infants <37 wGA, which can result in substantial morbidity associated with hospitalization (Summary Box). In the majority of these studies, the preterm infants were previously healthy, providing evidence that even those without underlying conditions, such as CLD (BPD) and CHD, are at increased risk of developing severe RSV infection.

The care of infants with severe RSV disease places a substantial burden on pediatric hospital resources and is costly. Although prematurity alone can significantly increase the risk of severe RSV disease and subsequent hospitalization, particularly in the first year of life, the presence of one or more other socioeconomic and environmental risk factors may increase an infant’s susceptibility to RSVH. Gestation-specific data are important for the planning of healthcare resource utilization and the use of RSV prophylactic agents. Further research is therefore needed on the prevalence and burden of RSV in different gestational age cohorts. Further prospective studies should also be undertaken to fully explore the changing risk of RSVH during the first year of life in preterm infants.

Summary box

| Level of evidencea | |

|---|---|

| Key statements/findings | |

| Studies have shown that preterm infants, particularly those born at lower gestational ages, are at high risk for RSVH and tended to have higher rates of hospitalization for RSV compared with otherwise healthy term infants | 1 (Level 1 studies: n = 8; risk of biasb: 10.9) |

| RSVH rates for preterm infants ranged from >100 per 1000 children to ~5 per 1000, with the highest rates shown in the lowest gestational age infants | 1 (Level 1 studies: n = 8; risk of biasb: 11.0) |

|

Compared to otherwise healthy/term infants, premature infants have Longer median hospital stays Increased complication rates Increased risk for ICU admission |

1 (Level 1 studies: n = 9; risk of biasb: 10.6) |

| A number of independent risk factors associated with RSVH in premature infants have been reported including exposure (e.g. proximity of birth to the RSV season, living with school-age siblings), social factors (e.g. smoking of mother during pregnancy or environmental smoking, reduced breast feeding), and biological factors (e.g. male sex, familial asthma) | 1 (Level 1 studies: n = 6; risk of biasb: 11.0) |

| Predictive models for RSVH in 32–35 wGA infants have been developed using 4 or 7 risk factors with areas under the ROC curves ranging from 0.687 to 0.791 (fair to good predictive accuracy) | 1 (Level 1 studies: n = 6; risk of biasb: 11.0) |

| Key areas for research | |

| In light of the continuing burden and long-term sequelae of severe RSV infection in otherwise healthy preterm infants, further research is needed on gestation-specific prevalence and burden of RSV disease to confirm the vulnerability of these children | |

| Further prospective studies should be undertaken to fully explore the changing risk of RSVH during the first year of life in preterm infants |

ICU intensive care unit, ROC receiver operating characteristic, RSV(H) respiratory syncytial virus (hospitalization), wGA weeks’ gestational age

aLevel 1: Local and current random sample surveys (or censuses); Level 2: Systematic review of surveys that allow matching to local circumstances; Level 3: Local non-random sample; Level 4: Case-series [26, 27]

bAverage RTI Item Bank Score [28], where 1 = very high risk of bias and 12 = very low risk of bias

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by AbbVie. Dr Joanne Smith, Julie Blake (Reviewers 1 and 2) and Dr Barry Rodgers-Gray (Reviewer 3) from Strategen Limited, undertook the systematic review following the protocol approved by the authors. Julie Blake and Dr Barry Rodgers-Gray also provided editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Support for this assistance was funded by AbbVie. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

The institute of Louis Bont received money for investigator initiated studies by MeMed, Astra Zeneca, AbbVie, and Janssen. The institute of Louis Bont received money for consultancy by Astra Zeneca, AbbVie, MedImmune, Janssen, Gilead and Novavax. Paul Checchia has acted as an expert advisor and speaker for AbbVie and has received honoraria in this regard. He has also received research grant funding from AstraZeneca. Brigitte Fauroux has received compensation as a neonatology board member from AbbVie. Josep Figueras-Aloy has acted as an expert advisor and speaker for AbbVie and has received honoraria in this regard. Paolo Manzoni has acted as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an expert advisor for AbbVie, TEVA, Medimmune, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and has received honoraria in this regard. Bosco Paes has received research funding from AbbVie Corporation and compensation as an advisor or lecturer from AbbVie and MedImmune. Eric Simões has received grant funding to his institution from Medimmune Inc., Glaxo Smith Kline Inc., and received consultancy fees to the institution, from AbbVie. Xavier Carbonell-Estrany has acted as an expert advisor and speaker for AbbVie and has received honoraria in this regard.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously published studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/F6E4F06044E2A44B.

References

- 1.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:543–546. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Schultz AF, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations among children less than 24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e341–e348. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF, Jr, Wright PF, Griffin MR. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in Medicaid. J Pediatr. 2000;137:865–870. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resch B. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants—an update on palivizumab prophylaxis. Open Microbiol J. 2014;11:71–77. doi: 10.2174/1874285801408010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueras-Aloy J, Carbonell-Estrany X, Quero J, for the IRIS Study Group Case-control study of the risk factors linked to respiratory syncytial virus infection requiring hospitalization in premature infants born at a gestational age of 33–35 weeks in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:815–820. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000136869.21397.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueras-Aloy J, Carbonell-Estrany X, Quero-Jiménez J, Fernández-Colomer B, Guzmán-Cabanās J, Echaniz-Urcelay I, et al. FLIP-2 Study: risk factors linked to respiratory syncytial virus infection requiring hospitalization in premature infants born in Spain at a gestational age of 32 to 35 weeks. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:788–793. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181710990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law BJ, Langley JM, Allen U, Paes B, Lee DSC, Mitchell M, et al. The Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada study of predictors of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection for infants born at 33 through 35 completed weeks of gestation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:806–814. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000137568.71589.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanken MO, Koffijberg H, Nibbelke EE, Rovers MM, Bont L, on behalf of the Dutch RSV Neonatal Network Prospective validation of a prognostic model for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in late preterm infants: a multicenter birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korsten K, Blanken MO, Nibbelke EE, Moons KGM, Bont L, On behalf of the Dutch RSV Neonatal Network Prediction model of RSV-hospitalization in late preterm infants: an update and validation study. Early Hum Dev. 2016;95:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straňák Z, Saliba E, Kosma P, et al. Predictors of RSV LRTI hospitalization in infants born at 33 to 35 weeks gestational age: a large multinational study (PONI) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Born too soon: The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth. 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44864/1/9789241503433_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed May 2016.

- 14.Horn SD, Smout RJ. Effect of prematurity on respiratory syncytial virus hospital resource use and outcomes. J Pediatr. 2003;143:S133–S141. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbonell-Estrany X, Pérez-Yarza EG, García LS, Cabañas JMG, Bòria EV, Atienza BB, IRIS Study Group Long-term burden and respiratory effects of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in preterm infants-the SPRING study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shefali-Patel D, Paris MA, Watson F, Peacock JL, Campbell M, Greenough A. RSV hospitalisation and healthcare utilisation in moderately prematurely born infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1055–1061. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1673-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenough A, Broughton S. Chronic manifestations of respiratory syncytial virus infection in premature infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S184–S187. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000188195.22502.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broughton S, Roberts A, Fox G, Pollina E, Zuckerman M, Chaudhry S, et al. Prospective study of healthcare utilisation and respiratory morbidity due to RSV infection in prematurely born infants. Thorax. 2005;60:1039–1044. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drysdale SB, Alcazar-Paris M, Wilson T, Smith M, Zuckerman M, Peacock JL, et al. Viral lower respiratory tract infections and preterm infants’ healthcare utilisation. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauskopf J, Margulis AV, Samuel M, Lohr KN. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations in healthy preterm infants: systematic review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:e229–e238. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th Edition. Editor: Larry K. Pickering, MD, FAAP; Associate Editors: Carol J. Baker, MD, FAAP; David W. Kimberlin, MD, FAAP; Sarah S. Long, MD, FAAP.

- 22.Samson L, Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14:521–532. doi: 10.1093/pch/14.8.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueras-Aloy J, Carbonell-Estrany X, Comité de Estándares de la SENeo. Actualización de las recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Neonatología para la utilización del palivizumab como profilaxis de las infecciones graves por el virus respiratorio sincitial. An Pediatr. 2015;82:199.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bollani L, Baraldi E, Chirico G, Dotta A, Lanari M, Del Vecchio A, Italian Society of Neonatology et al. Revised recommendations concerning palivizumab prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Ital. J Pediatr. 2015;41:97. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0203-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bont L, Checchia P, Fauroux B, Figueras-Aloy J, Manzoni P, Paes B, et al. Defining the Epidemiology and Burden of Severe Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection Among Infants and Children in Western Countries. Infect Dis Ther. 2016. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. “The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence”. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Accessed Mar 2016.

- 27.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. “The Oxford 2009 Levels of Evidence”. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed Mar 2016.

- 28.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, L Hartling. Assessing risk of bias and confounding in observational studies of interventions or exposures: further development of the RTI item bank. Methods Research Report. AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC106-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2013. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Accessed Mar 2016. [PubMed]

- 29.Fjaerli HO, Farstad T, Bratlid D. Hospitalisations for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in Akershus, Norway, 1993–2000: a population-based retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hervás D, Reina J, Yañez A, del Valle JM, Figuerola J, Hervás JA. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute bronchiolitis in children: differences between RSV and non-RSV bronchiolitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1975–1981. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deshpande SA, Northern V. The clinical and health economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease among children under 2 years of age in a defined geographical area. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.12.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang EE, Law BJ, Stephens D. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada (PICNIC) prospective study of risk factors and outcomes in patients hospitalized with respiratory syncytial viral lower respiratory tract infection. J Pediatr. 1995;126:212–219. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handal G, Logvinoff MM, Zegarra N, Allen L, Jesurun A, Levin G, et al. Prophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus in high-risk infants: administration of immune globulin and epidemiological surveillance of infection. Tex Med. 2000;96:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corsello G, Di Carlo P, Salsa L, Gabriele B, Meli L, Bruno S, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in a Sicilian pediatric population: risk factors, epidemiology, and severity. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:205–210. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark SJ, Beresford MW, Subhedar NV, Shaw NJ. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in high risk infants and the potential impact of prophylaxis in a United Kingdom cohort. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:313–316. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen HE, Siersma V, Andersen S, Gahrn-Hansen B, Mordhorst CH, Nørgaard-Pedersen B, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection—risk factors for hospital admission: a case-control study. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cilla G, Sarasua A, Montes M, Arostegui N, Vicente D, Pérez-Yarza E, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants in the Basque Country. Spain. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:506–513. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi GA, Medici MC, Arcangeletti MC, Lanari M, Merolla R, Paparatti U, et al. Risk factors for severe RSV-induced lower respiratory tract infection over four consecutive epidemics. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1267–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia CG, Bhore R, Soriano-Fallas A, Trost M, Chason R, Ramilo O, et al. Risk factors in children hospitalized with RSV bronchiolitis versus non-RSV bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1453–e1460. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forster J, Schumacher RF. The clinical picture presented by premature neonates infected with the respiratory syncytial virus. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:901–905. doi: 10.1007/BF01957502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olabarrieta I, Gonzalez-Carrasco E, Calvo C, Pozo F, Casas I, García-García ML. Hospital admission due to respiratory viral infections in moderate preterm, late preterm and term infants during their first year of life. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2015;43:469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanari M, Giovannini M, Giuffré L, Marini A, Rondini G, Rossi GE, the Investigators R.A.DA.R. Study Group et al. Prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Italian infants hospitalized for acute lower respiratory tract infections, and association between respiratory syncytial virus infection risk factors and disease severity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;33:458–465. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gijtenbeek RG, Kerstjens JM, Reijneveld SA, Duiverman EJ, Bos AF, Vrijlandt E. RSV infection among children born moderately preterm in a community-based cohort. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:435–442. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heikkinen T, Valkonen H, Lehtonen L, Vainionpää R, Ruuskanen O. Hospital admission of high risk infants from respiratory syncytial virus infection: implications for palivizumab prophylaxis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F64–F68. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.029710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedersen O, Herskind AM, Kamper J, Nielsen JP, Kristensen K. Rehospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants with extremely low gestational age or birthweight in Denmark. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:240–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van de Steen O, Miri F, Gunjaca M, Klepac V, Gross B, Notario G, et al. The burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus disease among children younger than 1 year in Central and Eastern Europe. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksson M, Bennet R, Rotzén-Östlund M, von Sydow M, Wirgart BZ. Population-based rates of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in children with and without risk factors, and outcome in a tertiary care setting. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haerskjold A, Kristensen K, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Nybo Andersen A-M, Ravn H, Stensballe LG. Risk factors for hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection: a population-based cohort study of Danish children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:61–65. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helfrich AM, Nylund CM, Eberly MD, Eide MB, Stagliano DR. Healthy Late-preterm infants born 33–36 + 6 weeks gestational age have higher risk for respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gouyon JB, Rozé JC, Guillermet-Fromentin C, Glorieux I, Adamon L, Di Maio M, et al. Hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in preterm infants at <33 weeks gestation without bronchopulmonary dysplasia: the CASTOR study. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:816–826. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hampp C, Kauf TL, Saidi AS, Winterstein AG. Cost-effectiveness of respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis in various indications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:498–505. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]