Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to study whether the trophoblasts carrying unbalanced translocation 11,22 [t(11;12)] display abnormal expression of trophoblastic genes and impaired functional properties that may explain implantation failure.

Methods

t(11;22) hESCs and control hESCs were differentiated in vitro into trophoblast cells in the presence of BMP4, and trophoblast vesicles (TBVs) were created in suspension. The expression pattern of extravillous trophoblast (EVT) genes was compared between translocated and control TBVs. The functional properties of the TBVs were evaluated by their attachment to endometrium cells (ECC1) and invasion through trans-well inserts.

Results

TBVs derived from control hESCs expressed EVT genes from functioning trophoblast cells. In contrast, TBVs differentiated from the translocated hESC line displayed impaired expression of EVT genes. Moreover, the number of TBVs that were attached to endometrium cells was significantly lower compared to the controls. Correspondingly, invasiveness of trophoblast-differentiated translocated cells was also significantly lower than that of the control cells.

Conclusions

These results may explain the reason for implantation failure in couple carriers of t(11;22). They also demonstrate that translocated hESCs comprise a valuable in vitro human model for studying the mechanisms underlying implantation failure.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-016-0781-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Human embryonic stem cells, Translocation, Trophoblasts, Implantation

Introduction

The human blastocyst is composed of the inner cell mass (ICM), which will give rise to all the cells and tissues in the body, and the outer layer of trophectoderm cells that will give rise to the embryonic part of the placenta. Implantation of the blastocyst in the uterus is one of the first requirements of a successful pregnancy. The cells that take part in the initial stages of implantation are the trophoblasts that emanate from the embryo and the endometrial cells of the recipient mother. During implantation, the trophectoderm cells differentiate into mononuclear cytotrophoblasts which give rise to syncytiotro phoblasts and to extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs). The syncytiotrophoblasts are responsible mainly for gas and nutrient exchange and for the production/secretion of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) [1]. The EVTs invade the uterine stroma and establish the maternal-fetal interface [2]. Female infertility caused by implantation failure can be attributed to either maternal factors, such as a non-receptive uterus [3], or to oocyte/embryonic factors, such as genetic, metabolic, or molecular abnormalities [4]. Women with repeated implantation failures (RIFs) have an increased incidence of chromosomal abnormalities, such as translocations, mosaicism, inversions, and deletions [5]. One of the chromosomal abnormalities is translocation, which is caused by rearrangement of segments between nonhomologous chromosomes [6, 7]. Carriers of chromosomal abnormalities have a high risk of creating aneuploid gametes, since chromatid segregation during the first meiotic division will result in about two-thirds of the gametes being genetically unbalanced, leading to unbalanced embryos. Most of these genetically abnormal embryos will either fail to implant or they will abort soon after implantation. The incidence of either of the parents being a carrier of a chromosomal abnormality, including translocation, has been reported to be between 2 and 8 % in couples with RIFs [8–10], and 12.5 % of those miscarriages were the result of embryos with unbalanced translocations [11].

There are several research models for studying implantation. The most common one is the targeted mouse mutations that cause placental defects, which significantly advanced our understanding of the genetic control of placental development and function [12]. Human in vitro models include choriocarcinoma-derived trophoblast cell lines (like JAR or JEG3 trophoblast cell lines) or primary trophoblast cultures derived from the placenta [13]. These models are mainly used to study embryo-endometrium interactions by creating trophoblast spheroids. Our understanding of human implantation and placental development is limited due to (1) the differences between mouse and human development, (2) the limited access to primary cytotrophoblasts which become non-proliferative after isolation, and (3) the fact that cell culture models are already committed to the trophoblast lineages and are thus inefficient for studying early lineage decisions. Therefore, additional research models for unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying embryo implantation in humans are needed.

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are an excellent in vitro tool for studying early stages of embryogenesis, including pre- and post-implantation stages as well as human placental development [14, 15]. hESCs are derived from the ICM of blastocyst-stage embryos and can be cultured indefinitely in vitro without losing their pluripotency [16, 17]. On the other hand, they can be differentiated into virtually any cell type in the body, including extra-embryonic lineages (cyto- and syncytiotrophoblasts) [18–20], and can, therefore, serve as an invaluable tool for studying early stages of implantation. We have recently derived four hESC lines carrying unbalanced translocations known to be correlated with implantation failure [21]. Among them is the unbalanced reciprocal t(11;22) hESC line that harbors a partial monosomy, der(11) t(11;22) (q23;q12), the most common recurrent non-Robertsonian constitutional reciprocal translocation in humans, which has been reported in many unrelated families [22, 23]. We have recently reported that the unbalanced t(11;22) hESC line demonstrates impaired differentiation into trophoblasts, as evidenced by reduced and delayed secretion of β-hCG concomitant with impaired expression of trophoblastic genes [24]. Using the same unique translocated hESCs, the current study aims to further elucidate the molecular and functional properties of the trophoblasts in order to explain implantation failure in women with t(11;22).

Materials and methods

hESC derivation and culture

Seven embryos diagnosed as having unbalanced translocation (11,22) were plated, and one translocated hESC line was obtained [24]. The study protocol was approved by the Israeli National Ethics Committee (7/04-043), and the embryos were donated by the parents for derivation of hESC lines after they signed an informed consent. Three lines were used as control; Hues 64 and Hues 6 [25], kindly provided by Dr. Douglas Melton (HSCI), as well as HEFX1 [26, 27]. Karyotype analysis was performed as previously described in depth elsewhere [27]. The experimental t(11,22) hESC line is able to self-renew in vitro while remaining undifferentiated, demonstrating a typical hESC line morphology, and to express pluripotent markers, such as Oct4 Nanog and SSEA-3 (Fig. 2 [24]).

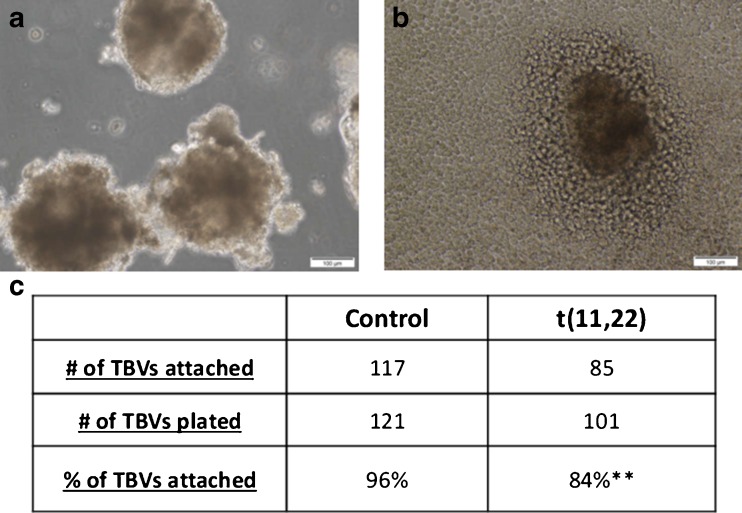

Fig. 2.

Attachment of TBVs to endometrial cells. a Trophoblast vesicles (TBV) derived from BMP4-treated hESCs. b Bright field picture of a TBV attached to endometrial cells (ECC1) 2 days after plating. c Number of attached TBVs to endometrium cells per number of TBVs plated. Data represent at least three different biological experiments performed on each line. **P < 0.01

hESC cultures were grown on feeder cell layers of mitomycin C-inactivated treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and cultured in hESC media (knockout [KO] DMEM supplemented with 20 % KO serum replacement, 1 % nonessential amino acids, 1 mM l-glutamine, 0.5 % insulin transferrin-selenium, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 mg/mL streptomycin, 0.1 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and 8 ng/mL bFGF). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5 % CO2.

Differentiation into trophoblasts

To induce trophoblast differentiation, undifferentiated hESCs were passaged with collagenase type IV and plated on 6-well plates coated with matrigel in a density of 80–100,000 cells per well. The attached cells were cultured in MEF-conditioned medium composed of KO-DMEM (Gibco, Surrey, UK), supplemented with 20 % KO serum replacement (Gibco), 1 % non-essential amino acids (Biological Industries), 1 mM l-glutamine (Biological Industries), 0.5 % insulin-transferrin-selenium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 mg/mL streptomycin (Biological Industries), and 0.1 mM beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 8 ng/mL bFGF for 2 days. The cells were then treated with feeder free-conditioned medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL human BMP4 (R&D).

Endometrial cells and steroid treatment

The ECC1 endometrial cell line was treated with 17 β-estradiol (OE2, 10−8 M) for 24 h, followed by OE2 (10−8 M) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 10−6 M) for an additional 24 h.

Gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and decontaminated by DNAseI (Invitrogen). RNA (300 ng–1 μg) was reversed transcribed using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed using SYBR green (Thermo-Scientific and Quanta Biosciences). Relative transcript levels (∆∆Ct) were calculated relative to GAPDH. All primer pairs were checked for specificity and calibrated to ensure high efficiency (list of primers, Supplementary Table 1).

Trophoblast vesicle (TBV) formation

The hESCs were differentiated into trophoblasts by BMP4 treatment (as described above) for 7 days. On day 7 of differentiation, the cells were detached from the plates by scraping, resuspended in hESC medium, and transferred into an uncoated 6-well plate which was placed in an incubator [28].

Attachment assay

Control and translocated trophoblast vesicles, with similar morphological features (i.e., size and shape), were transferred to a 96-well dish coated with steroid-treated endometrium cells (plated with a density of 12*104 ECC1 cells per well), one TBV in each well, to allow their attachment. These cultures were incubated undisturbed at 37° in a 5 % CO2 humidified chamber. Following 48 h of incubation, the cultures were washed several times with PBS, and the number of attached vesicles was counted.

Invasion assay

The hESCs were counted and plated on matrigel-coated 6.5-mm trans-well inserts with polycarbonate membrane filters (Corning). The inserts were placed in 24-well plates containing 500-μL hESC medium, and the cells were cultured in 150-μL hESC medium and treated with BMP4. The cells on the upper side of the trans-well were removed by a cotton swab on days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. The invaded cells on the bottom side of the trans-well were stained with DAPI, and 5–6 representative fields were photographed by a florescence microscope (Olympus IX51). Fluorescent intensity was calculated by the ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Gene expression values were compared by one-tailed Student’s t test using SPSS version 19. The attachment rate of the TBVs to the endometrium cells was compared by the Chi square test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The expression of extravillous trophoblast genes in trophoblastic vesicles derived from hESCs

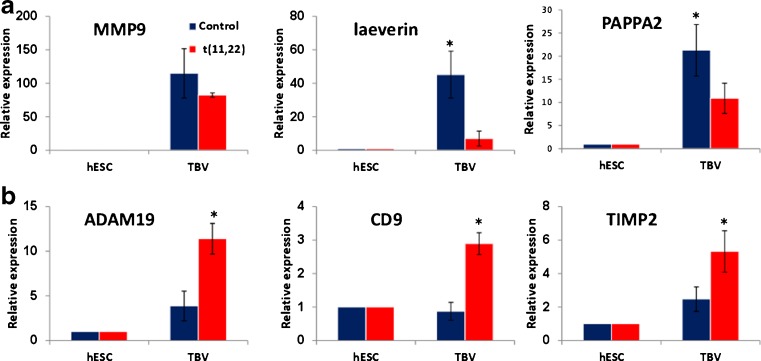

We had previously shown that trophoblasts which were derived in vitro from translocated hESC display decreased and delayed secretion of β-hCG compared to controls [24]. In the current study, we differentiated these t(11;22) hESCs into TBVs in the presence of BMP4 [see Materials and methods “Trophoblast vesicles (TBVs) formation”] in order to model the early stages of implantation of translocated blastocysts. Our results showed that control TBVs continued to secrete β-hCG even after 7 days in suspension (data not shown). The TBVs were further analyzed for the EVT genes (MMP9, laeverin, PAPPA2, ADAM19, CD9, and TIMP2), which had previously been shown to be expressed in EVT derived from human first-trimester trophoblasts [29] and from BMP4-treated hESCs [30] (Fig. 1a, b). The expression of most EVT genes (MMP9, laeverin, PAPPA2, ADAM19, and TIMP2) was significantly increased upon differentiation into TBVs in both control and translocated cells. However, their increase in the control TBVs was significantly higher than in the translocated TBVs (see MMP9, Laeverin, and PAPPA2 in Fig. 1a). In contrast, ADAM19, CD9, and TIMP2 were significantly upregulated in the translocated cells compared to the control TBVs (Fig. 1b). These results demonstrated an aberrant expression of EVT genes in translocated TBVs.

Fig. 1.

Expression of extravillous trophoblast markers in trophoblast vesicles. a–b qRT-PCR analysis of extravillous trofoblast genes in mean of at least three control WT lines (blue) and Lis05_t(11;22) (red) hESCs. Relative transcription levels of each gene were analyzed in undifferentiated hESCs (day 0) and in TBVs after 7 days of in vitro trophoblastic differentiation. Data are presented as mean ± standard error and represent two–three experiments performed on each line. *P < 0.05

Attachment of trophoblastic vesicles to endometrial cells

In order to further explore the reason for implantation failure in t(11;22) hESCs, we performed a functional attachment assay by evaluating the attachment potential of TBVs to endometrial cells. TBVs were plated on hormone-treated ECC1 endometrial cells, and the number of attached translocated TBVs was significantly lower than that of controls (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2c).

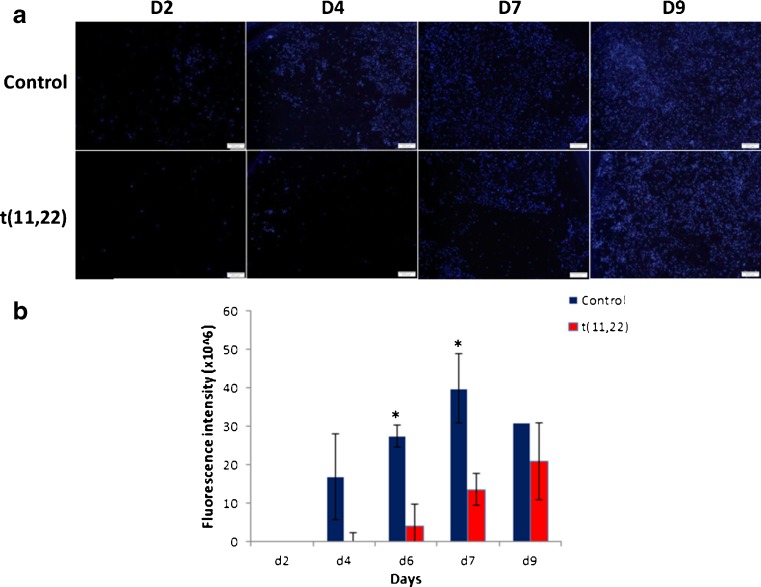

Invasion potential of trophoblast cells

In order to compare the invasiveness of translocated-derived trophoblasts to that of control trophoblasts, hESCs were plated on matrigel-coated trans-well inserts and exposed to BMP4 trophoblast differentiation conditions. The translocated cells invaded the matrigel-coated membrane less efficiently, i.e., the invasiveness was delayed concomitant with the decreased number of trophoblasts invading the membranes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Invasion of trophoblastic cells through transwells. a Immunofluorescent images of invaded cells at different time points following trophoblast differentiation. Control and translocated hESCs were plated on matrigel-coated transwells and treated with BMP-4 for 9 days. Nuclei of invaded cells were stained with DAPI. b Total fluorescence intensity of the invaded cells following trophoblast differentiation on matrigel-coated transwells. Data are presented as mean + SEM of five different fields analyzed by the ImageJ software. *P < 0.05

Discussion

Carriers of balanced t(11;22), the most common reciprocal translocation in humans, are at high risk of creating gametes with unbalanced translocations, leading to RIFs. RIFs can be caused by the improper development of either the ICM, which gives rise to all the embryonic tissues, or the trophectoderm, which creates the extra-embryonic tissues. We derived the first hESC line carrying unbalanced t(11;22) and showed that its ability to differentiate into trophoblasts is impaired, as evidenced by reduced and delayed secretion of β-hCG concomitant with impaired expression of the trophoblastic genes CDX2, KRT7, GCM1, PPARG, KLF4, TP63, and CGA [24].

In the current work, we showed that TBVs derived from control hESCs secreted β-hCG and expressed EVT genes as expected from functioning trophoblast cells, as was recently shown by Yin-Lau Lee et al. [31]. β-hCG levels were not measured in the TBVs derived from the translocated line. TBVs differentiated from the translocated hESCs displayed impaired expression of EVT genes, and the number of attached TBVs to endometrium cells was significantly lower compared to the controls. Correspondingly, invasiveness of translocated trophoblast cells was also significantly lower than that of controls.

Trophectoderm is the first differentiated cell type that already appears in the preimplantation mammalian embryo. It differentiates to the trophoblast lineage and contributes to implantation and to formation of the placenta. We now created, for the first time, TBVs from translocated hESCs, as had been demonstrated by Xu et al. for WT hESCs [32], in an attempt to model the outer layer of blastocysts, i.e., the trophectoderm, and to compare their trophoblast molecular and functional properties. We examined the expression of six trophoblastic genes: MMP9, a positive regulator of trophoblast invasiveness [33]; laeverin, a specific cell surface marker for human EVT which plays a regulatory role in EVT migration [34]; PAPPA2, a pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) which is highly expressed by human placental trophoblasts [35]; ADAM19 metallopeptidase domain 19 which is a ligand recognized by NK cells; CD9, an EVT-specific marker which is expressed in trophoblast-enriched decidua [29, 30] and encodes to protein functions in many cellular processes, including differentiation, adhesion, and signal transduction [36]; and TIMP2, a primary product of the decidua which controls EVT invasion [37]. All six genes were previously shown to be expressed in human trophoblast cells, as well as in EVTs during migration and invasion as part of the implantation process [29, 30].

Our results showed that control TBVs expressed EVT genes, indicating the existence of EVT-like cells. These EVT genes, however, were differentially expressed between the translocation and the control TBVs. The abnormal expression of the EVT genes in the translocated cells may indicate that the differentiation of these cells into EVTs is impaired. It is important to mention that all of these genes were found to be highly expressed in purified first-trimester trophoblasts [29] and that only some of them were expressed in BMP4-treated hESCs (ADAM19, PAPPA2, and TIMP2) [30].

The process of implantation begins in the second week of embryo development and includes apposition of the blastocyst to the uterine wall and stable adhesion to the uterine epithelium followed by invasion. The invasion process starts with the penetration of the syncytiotrophoblasts through the uterus epithelium and ends by the infiltration of cytotrophoblasts and EVTs into the endometrium [38]. The early stages of implantation had been examined by analyzing the attachment of mouse embryos or spare human in vitro fertilization embryos to endometrial cells (either primary cells extracted from endometrial biopsies or endometrial cell lines) as well as the attachment of trophoblast spheroids [31, 39–42]. Our current model, in which hESCs were differentiated into TBVs, enabled us to study early stages of implantation in WT and mutated embryos and, by doing so, to explore the reasons for implantation failure in chromosomal translocation. Our results showed that most TBVs from both t(11;22) and control hESCs were capable of attaching to hormone-treated ECC1 endometrial cells. Nevertheless, the number of attached t(11;22) TBVs was significantly lower than that of the controls. These findings indicate that translocated cells have an impaired capacity to attach to endometrial cells, which can suggest a possible reason for RIF of unbalanced translocated embryos.

This model is based on hESCs carrying the natural translocaton, and it is currently the only human in vitro model for RIFs in translocation carriers. Models for attachment and invasiveness generally make use of co-culture systems of embryos plated on endometrial epithelial or stromal cells in order to mimic the complex three-dimensional tissue architecture of the implantation site. However, application of this model in humans is limited due to the scarcity of human embryos for research, whereupon most studies use either mouse embryos or human trophoblast spheroids [13, 43–46]. Such co-culture trans-well systems have been employed to explore the paracrine effect of trophoblast- and endometrial stromal cell-secreted factors on the invasive capability of trophoblast cells [44]. The trans-well model systems (endometrial-coated filter inserts) comprise an excellent model for trophoblast invasion and endometrial epithelial/stromal cell interaction [47, 48] in which the number of invaded trophoblast cells through the endometrium can be quantified [13]. Telugu et al. used the matrigel invasion assay in order to test whether BMP4-treated hESCs contain a population of mobile, potentially invasive trophoblasts [39]. Using this invasion model but with our unique translocated hESC line, we were now able to show that trophoblasts that had differentiated from t(11;22) hESCs migrate and invade the trans-well system significantly less efficiently compared to the controls. Taken together, the results of migration and the invasion assay imply that implantation of translocated cells is impaired.

In conclusion, unbalanced t(11;22) hESCs demonstrated impaired differentiation into all types of trophoblast cells, i.e., cytotrophoblasts, syncytiotrophoblasts, and (most likely) extravillous trophoblasts. The functional properties of translocated trophoblasts were reduced compared to control cells, which may explain implantation failure of unbalanced t(11;22) embryos. However, since direct differentiation was shown only for the trophoblast lineage, we cannot rule out the possibility that abnormal development of other lineages could also contribute to the miscarriages of unbalanced embryos. In addition, we are aware that the limitation of this work is that it was done on only one variant of only one translocation. This is due to the scarcity of translocated hESC lines. At the same time, the translocation t(11;22) is the most frequent balanced translocation in the human population. Further studies on hESC lines with different variants of different translocations are needed to validate our conclusion that the correlation between impaired trophoblast differentiation and implantation failure also applies to other translocations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 29 kb)

Acknowledgments

Esther Eshkol for editorial assistance.

Authors’ roles

Y.K. and D.B-Y planned and supervised the project, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and approved it. A.S. carried out experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health (Israel).

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule

hESCs differentiation into extravillous trophoblast cells is impaired both molecularly and functionally, as indicated by faulty expression of extravillous genes and reduced ability to attach and invade the endometrium.

Dalit Ben-Yosef and Yael Kalma contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Potgens AJ, Schmitz U, Bose P, Versmold A, Kaufmann P, Frank HG. Mechanisms of syncytial fusion: a review. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl A):S107–13. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts RM, Fisher SJ. Trophoblast stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:412–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revel A. Defective endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1028–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das M, Holzer HE. Recurrent implantation failure: gamete and embryo factors. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1021–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raziel A, Friedler S, Schachter M, Kasterstein E, Strassburger D, Ron-El R. Increased frequency of female partner chromosomal abnormalities in patients with high-order implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:515–9. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evsikov S, Cieslak J, Verlinsky Y. Effect of chromosomal translocations on the development of preimplantation human embryos in vitro. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:672–7. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandeweyer G, Kooy RF. Balanced translocations in mental retardation. Hum Genet. 2009;126:133–47. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franssen MT, Musters AM, van der Veen F, Repping S, Leschot NJ, Bossuyt PM, et al. Reproductive outcome after PGD in couples with recurrent miscarriage carrying a structural chromosome abnormality: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:467–75. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutta UR, Rajitha P, Pidugu VK, Dalal AB. Cytogenetic abnormalities in 1162 couples with recurrent miscarriages in southern region of India: report and review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:145–9. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elghezal H, Hidar S, Mougou S, Khairi H, Saad A. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in couples with recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:721–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochhar, P.K. and P. Ghosh, Reproductive outcome of couples with recurrent miscarriage and balanced chromosomal abnormalities. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Rossant J, Cross JC. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:538–48. doi: 10.1038/35080570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weimar CH, Post Uiterweer ED, Teklenburg G, Heijnen CJ, Macklon NS. In-vitro model systems for the study of human embryo-endometrium interactions. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:461–76. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dvash T, Ben-Yosef D, Eiges R. Human embryonic stem cells as a powerful tool for studying human embryogenesis. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:111–7. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000228349.24676.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vazin T, Freed WJ. Human embryonic stem cells: derivation, culture, and differentiation: a review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28:589–603. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reubinoff BE, Pera MF, Fong CY, Trounson A, Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drukker M, Tang C, Ardehali R, Rinkevich Y, Seita J, Lee AS, et al. Isolation of primitive endoderm, mesoderm, vascular endothelial and trophoblast progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:531–42. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudheer, S., R. Bhushan, B. Fauler, H. Lehrach, and J. Adjaye, FGF inhibition directs BMP4-mediated differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells to syncytiotrophoblast. Stem Cells Dev, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Giakoumopoulos M, Golos TG. Embryonic stem cell-derived trophoblast differentiation: a comparative review of the biology, function, and signaling mechanisms. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:R33–45. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Yosef D, Malcov M, Eiges R. PGD-derived human embryonic stem cell lines as a powerful tool for the study of human genetic disorders. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;282:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraccaro M, Lindsten J, Ford CE, Iselius L. The 11q;22q translocation: a European collaborative analysis of 43 cases. Hum Genet. 1980;56:21–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00281567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong SJ, Goldman AS, Speed RM, Hulten MA. Meiotic studies of a human male carrier of the common translocation, t(11;22), suggests postzygotic selection rather than preferential 3:1 MI segregation as the cause of liveborn offspring with an unbalanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:601–9. doi: 10.1086/303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shpiz, A., Y. Kalma, T. Frumkin, M. Telias, A. Carmon, A. Amit, et al., Human embryonic stem cells carrying an unbalanced translocation demonstrate impaired differentiation into trophoblasts: an in vitro model of human implantation failure. Mol Hum Reprod, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bock C, Kiskinis E, Verstappen G, Gu H, Boulting G, Smith ZD, et al. Reference Maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell. 2011;144:439–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Yosef D, Amit A, Malcov M, Frumkin T, Ben-Yehudah A, Eldar I, et al. Female sex bias in human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:363–72. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eiges R, Urbach A, Malcov M, Frumkin T, Schwartz T, Amit A, et al. Developmental study of fragile X syndrome using human embryonic stem cells derived from preimplantation genetically diagnosed embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:568–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu RH, Chen X, Li DS, Li R, Addicks GC, Glennon C, et al. BMP4 initiates human embryonic stem cell differentiation to trophoblast. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1261–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apps R, Sharkey A, Gardner L, Male V, Trotter M, Miller N, et al. Genome-wide expression profile of first trimester villous and extravillous human trophoblast cells. Placenta. 2011;32:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Telugu BP, Adachi K, Schlitt JM, Ezashi T, Schust DJ, Roberts RM, et al. Comparison of extravillous trophoblast cells derived from human embryonic stem cells and from first trimester human placentas. Placenta. 2013;34:536–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YL, Fong SW, Chen AC, Li T, Yue C, Lee CL, et al. Establishment of a novel human embryonic stem cell-derived trophoblastic spheroid implantation model. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2614–26. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu RH. In vitro induction of trophoblast from human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Med. 2006;121:189–202. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-983-4:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moindjie H, Santos ED, Loeuillet L, Gronier H, de Mazancourt P, Barnea ER, et al. Preimplantation factor (PIF) promotes human trophoblast invasion. Biol Reprod. 2014;91:118. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.119156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horie A, Fujiwara H, Sato Y, Suginami K, Matsumoto H, Maruyama M, et al. Laeverin/aminopeptidase Q induces trophoblast invasion during human early placentation. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1267–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner PK, Otomo A, Christians JK. Regulation of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A2 (PAPPA2) in a human placental trophoblast cell line (BeWo) Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirano T, Higuchi T, Katsuragawa H, Inoue T, Kataoka N, Park KR, et al. CD9 is involved in invasion of human trophoblast-like choriocarcinoma cell line, BeWo cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:168–74. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen M, Bischof P. Factors regulating trophoblast invasion. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64:126–30. doi: 10.1159/000101734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staun-Ram E, Shalev E. Human trophoblast function during the implantation process. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meseguer M, Aplin JD, Caballero-Campo P, O’Connor JE, Martin JC, Remohi J, et al. Human endometrial mucin MUC1 is up-regulated by progesterone and down-regulated in vitro by the human blastocyst. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:590–601. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.2.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentin-Ley U, Sjogren A, Nilsson L, Hamberger L, Larsen JF, Horn T. Presence of uterine pinopodes at the embryo-endometrial interface during human implantation in vitro. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:515–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lalitkumar PG, Lalitkumar S, Meng CX, Stavreus-Evers A, Hambiliki F, Bentin-Ley U, et al. Mifepristone, but not levonorgestrel, inhibits human blastocyst attachment to an in vitro endometrial three-dimensional cell culture model. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:3031–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh H, Nardo L, Kimber SJ, Aplin JD. Early stages of implantation as revealed by an in vitro model. Reproduction. 2010;139:905–14. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gonzalez M, Neufeld J, Reimann K, Wittmann S, Samalecos A, Wolf A, et al. Expansion of human trophoblastic spheroids is promoted by decidualized endometrial stromal cells and enhanced by heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor and interleukin-1 beta. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:421–33. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estella C, Herrer I, Atkinson SP, Quinonero A, Martinez S, Pellicer A, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity in human endometrial stromal cells promotes extracellular matrix remodelling and limits embryo invasion. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmberg JC, Haddad S, Wunsche V, Yang Y, Aldo PB, Gnainsky Y, et al. An in vitro model for the study of human implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gellersen B, Wolf A, Kruse M, Schwenke M, Bamberger AM. Human endometrial stromal cell-trophoblast interactions: mutual stimulation of chemotactic migration and promigratory roles of cell surface molecules CD82 and CEACAM1. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:80. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.106724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aplin JD. In vitro analysis of trophoblast invasion. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:45–57. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lash GE, Hornbuckle J, Brunt A, Kirkley M, Searle RF, Robson SC, et al. Effect of low oxygen concentrations on trophoblast-like cell line invasion. Placenta. 2007;28:390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 29 kb)