Abstract

The means by which brains transform sensory information into coherent motor actions is poorly understood. In flies, a relatively small set of descending interneurons are responsible for conveying sensory information and higher-order commands from the brain to motor circuits in the ventral nerve cord. Here, we describe three pairs of genetically identified descending interneurons that integrate information from wide-field visual interneurons and project directly to motor centers controlling flight behavior. We measured the physiological responses of these three cells during flight and found that they respond maximally to visual movement corresponding to rotation around three distinct body axes. After characterizing the tuning properties of an array of nine putative upstream visual interneurons, we show that simple linear combinations of their outputs can predict the responses of the three descending cells. Last, we developed a machine vision-tracking system that allows us to monitor multiple motor systems simultaneously and found that each visual descending interneuron class is correlated with a discrete set of motor programs.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Most animals possess specialized sensory systems for encoding body rotation, which they use for stabilizing posture and regulating motor actions. In flies and other insects, the visual system contains an array of specialized neurons that integrate local optic flow to estimate body rotation during locomotion. However, the manner in which the output of these cells is transformed by the downstream neurons that innervate motor centers is poorly understood. We have identified a set of three visual descending neurons that integrate the output of nine large-field visual interneurons and project directly to flight motor centers. Our results provide new insight into how the sensory information that encodes body motion is transformed into a code that is appropriate for motor actions.

Keywords: ethology, flight, self-motion estimation, vision

Introduction

A primary function of the brain is to encode information from several different sensory modalities and forward integrated commands to the motor systems that regulate behavioral output. A key step in many sensory–motor transformations is to translate the coordinates of sensory systems into a map of spatially directed motor actions. Many animals achieve this by independently encoding orthogonal axes of movement. In the vestibulocerebellar system, for instance, the visually sensitive neurons responsible for stabilizing eye and head movements encode approximately orthogonal axes of rotation (Graf et al., 1988; Leonard et al., 1988; Wylie et al., 1998). Similarly, groups of tegmental neurons in the brainstem of barn owls control up, down, left, and right movements of the head (Masino and Knudsen, 1990). These independent neural circuits constitute an intermediate processing stage in the brain between more peripheral sensory circuits and the motor systems responsible for head movement.

Arthropods also exhibit sophisticated systems for encoding self-motion, as exemplified by the well characterized lobula plate tangential cells (LPTCs), visual interneurons that reside in a fourth-order visual neuropil in flies (Hausen, 1984; Krapp and Hengstenberg, 1996; Krapp et al., 1998). In the blowfly, Calliphora, a class of descending interneurons, the descending neurons of the ocellar and vertical system (DNOVS), are thought to integrate information from the LPTCs and convey it toward motor centers in the thoracic ganglion (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Gronenberg and Strausfeld, 1990; Strausfeld and Gronenberg, 1990; Strausfeld, 1991). In particular, DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 respond to visual stimuli mimicking ego motion in a manner that is similar to the upstream LPTCs (Wertz et al., 2009). These studies were performed in restrained blowflies, but recent work has shown that the properties of the LPTCs are altered by behavioral state (Chiappe et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2011; Maimon et al., 2010; Suver et al., 2012), so it is likely that the response properties of downstream neurons may also differ between quiescent and flying animals. Further, the intermediate position of the descending cells within the sensory–motor pathways raises intriguing questions regarding their rotational tuning properties. For example, do the neurons simply relay information based on the properties of their sensory inputs or do they encode axes of rotation that are matched to the motor circuits that they innervate?

To characterize the transformation that occurs between sensory inputs in the brain and motor output in a behaving animal, we performed an anatomical and physiological screen for candidate neurons that receive visual inputs in the central brain and project to motor neuropil in the thoracic ganglion of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. We identified three functional classes of visual descending neurons (two of which we believe are homologs of the blowfly DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 neurons) and then characterized their properties using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in tethered, flying animals. The anatomy of these descending neurons at the level of light microscopy is consistent with their each receiving input from a distinct set of LPTCs. We also measured the directional tuning of these LPTC subgroups and found that simple linear combinations of their output predict the responses of the descending neurons accurately. To construct a framework in which to explore the functional role of the descending neurons in different components of flight behavior, we developed a system to track multiple motor systems simultaneously. The tuning of the three cells was found to be well correlated with that of different motor components of flight behavior.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

We targeted specific neurons for patch-clamp recordings using the following driver lines: DB331-Gal4 [vertical system (VS) 1–6, horizontal system north (HSN), HS east (HSE), HS south (HSS); Scott et al., 2002, FBti0115113], R20C05-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2, DNHS1, VS1–6; FBtp0058222, Bloomington Stock #48883). R94H09-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2; FBtp0064267, Bloomington Stock #40705), and R15C02-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2, DNHS1, HSN, HSE, HSS; FBtp0057772, Bloomington Stock #49262). We expressed cytoplasmic GFP in these lines using the reporter line 10XUAS-IVS-Syn21-GFP-p10 (Pfeiffer et al., 2012, FBtp0073107) with the w+ gene reintroduced on the first chromosome using the Heisenberg Canton-S background. The GFP signal in DNHS1 was very faint in both drivers in which we located it using this reporter construct. For all experiments, we used 2- to 3-d-old females raised on standard Drosophila medium at 25°C with a 14 h/10 h light/dark schedule. To encourage flight and to aid in tracking abdomen kinematics for behavioral experiments, we removed all of the legs but the metathoracic leg femurs.

Electrophysiology.

We performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in tethered flies using techniques and solutions described previously (Wilson and Laurent, 2005; Maimon et al., 2010). We briefly anesthetized animals with cold and used UV glue (an approximate 1:4 ratio of Loctite 3104 and CE 395 UV Glue; Twin City Supply to achieve the desired viscosity and curing speed) to affix them to custom-made fly holders (Maimon et al., 2010; holder modification is described in Suver et al., 2012). Using a small (30 G) hypodermic needle, we cut open a window in the back of the fly's head to expose the neuropil. We cut muscle 1 and removed any fat to expose the cell bodies of interest. We gained further access to the cell bodies of interest by locally applying collagenase type IV (Worthington; 0.5% in extracellular saline) with a low-resistance patch pipette to gently break through the sheath and clean the cell bodies of interest. We continuously perfused saline over the brain. Using an in-line heater/cooler (CL-100 and SC-20; Warner Instruments), we briefly raised the bath temperature to ∼30°C to increase effectiveness of the collagenase during the desheathing step and then lowered the temperature to 20°C for the remainder of the experiment.

To visualize the cells, we added 20 μm Alexa Fluor 568 (#A-10437; Invitrogen) and 13 mm biocytin (#B1093; Invitrogen) to the intracellular solution. We used electrodes with resistances of 4.2–8.0 MΩ (average ∼6 MΩ). The average resting potential of DNOVS1 was −46.7 mV after an experimentally measured junction potential (−13 mV) was added. The average access resistance (Racc) for DNOVS1 cells was 32.1 MΩ. The average resting potential and Racc for DNOVS2 were −40.9 mV and 39.2 MΩ, respectively. For DNHS1, the average resting potential and Racc, respectively, were −43.1 mV and 29.0 MΩ. For VS and HS cells, the average resting potentials were −44.72 and −50.0 mV, respectively, and the average Racc were 41.7 and 32.1 MΩ, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging.

We typically used the Alexa Fluor 568 intracellular dye fill signal to identify VS and HS cell dendrites, which are relatively superficial. However, for descending neurons or any VS or HS cells with a weaker Alexa Fluor 568 signal, we carefully removed the fly from the holder immediately after a recording and dissected its brain in 4% paraformaldehyde. We fixed brains in 4% paraformaldehyde for a total of 20 min. We incubated brains in a primary antibody solution containing 5% normal goat serum in PBS-Tx, mouse anti-nc82 (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), and rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Invitrogen) for 2–3 h at room temperature on an oscillator. We then incubated the brains in a secondary antibody solution containing 5% normal goat serum in PBS-Tx, goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 (1:250; Invitrogen), and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250; Invitrogen) for 2–3 h at room temperature on an oscillator. We mounted the brains in Vectashield (Vector Labratories) and imaged them on a Leica SP5 II confocal microscope under 63× oil objective at 1 μm section intervals. Axon diameter was estimated in DNOVS1, DNOVS2, and DNHS1 by averaging across five, five, and three flies, respectively. For each brain, the diameter was measured at multiple points along the cervical connective or the anterior-most region in the thoracic ganglion from a maximum projection image. We traced neurons using the ImageJ Simple Neurite Tracer plug-in (Longair et al., 2011).

Photoactivation.

We expressed photoactivatable (PA)-GFP pan-neuronally using an nSyb-LexA driver and expressed tdTomato in LPTC terminals using the DB331-Gal4 driver. The full genotype of the flies was DB331-Gal4, UAS-TdTomato; +; nSyb-Lexa65attP2, LexAop-mPA-GFP. We performed the activation on a Prarie Ultima IV multiphoton microscope with a Nikon 40× NIR Apo objective water-immersion lens (0.8 numerical aperture) and PrairieView software. We located VS output terminals using the tdTomato signal (illuminated with 940 nm light) and activated a 15 μm square region around these using 710 nm light. We activated 2 planes in this region spaced 4 μm apart. We performed two activation scans separated by a 600 ms rest period to reduce photobleaching of already activated PA-GFP (this allows unactivated PA-GFP to diffuse into the area and activated PF-GFP to diffuse out). Each activation scan consisted of 100 repetitions of blocks of 16 separated by a 15 ms pause. Total activation time took ∼1 h.

Visual stimulus.

For electrophysiological and behavioral experiments, we presented flies with a set of stimulus patterns on a green (570 nm), 32- by 96-pixel LED display (Reiser and Dickinson, 2008; www.iorodeo.com). The display spanned ∼−90° to +90° of the fly's horizontal visual field (measured span was 89.52°) and 20° above and 35° below the horizon. Each pixel spanned ∼2.25° at the center of the display. For the physiology experiments, we centered the fly in the arena by aligning its wing hinges to a static overlaid image on the camera view. We measured an estimated variation of ∼1.5 pixels (3.4°) in heading alignment among flies. For pure behavior experiments, we aligned the fly using software handles for the three camera views in Kinefly (see below). To simulate visual rotation, we presented patterns of dots revolving around a series of 13 horizontal axes at 15° intervals between −90° and +90°. The visual patterns used in our experiments may be viewed in the supplementary material of a prior publication (Weir and Dickinson, 2015). Briefly, we constructed patterns of optic flow by rotating and translating a virtual cloud of random bright points that we then projected onto the cylindrical coordinates of the display. For rotatory patterns, all point sources moved as if they were fixed to a sphere that rotated at 22.5°/s. To simulate translational motion, we created a virtual array of points randomly arranged in 3 dimensions (20 points m3) and assumed that the fly moved at 1 m/s. We assumed that the fly could not see points >2 m away and that the points subtended 1 pixel regardless of distance to the observer. We presented the fly with these different rotating and translating star-field stimuli in pseudorandom order. Each trial consisted of 2 s of motion with 2 s stationary periods before and after the motion bouts.

Behavioral measurements.

During electrophysiological experiments, we monitored the fly's behavioral state using a Prosilica GE680 camera running at 66 Hz with an Infinistix 90 lens (Infinity Photo Optical) and open source tracking software written by Andrew Straw (https://github.com/motmot/strokelitude; Maimon et al., 2010). We illuminated the fly from behind using high-intensity infrared diodes (880 nm; Golden Dragon; Osram) coupled to fiber optics. We initiated flight with a brief air puff directed toward the head of the fly.

For behavioral experiments using the Kinefly tracking software (see description of software below), we briefly anesthetized flies by cooling them to ∼4°C and then glued them to 0.005-inch-diameter tungsten pins (#716000; A-M Systems) with blue-light-curing glue (Bondic). We centered flies and monitored them with three cameras (Basler acA640–100 gm, each with a Computar MLM3X-MP 2/3″ Megapixel C-Mt 3.3X Macro Zoom lens). One camera was placed directly below the fly, one to the right, and one to the left. We illuminated the fly from the front using two infrared diodes (driver: LEDD1B, and LED: M850F2; Thorlabs) each coupled to a fiber-optic cable (FT1500EMT; Thorlabs). We elicited flight with a brief puff of air delivered to the fly's head.

Kinefly: real-time, open source modular tracking software.

We designed a behavioral tracking system that allows us to monitor multiple motor systems in real time. This software, Kinefly, is a computer-vision-based tool designed to measure kinematic variables of a tethered winged insect. There are facilities for measuring wing, abdomen, head, and leg positions; for performing image stabilization on a moving body part (to allow measurement of details further down the kinematic tree); and for measuring motion frequency. We set Kinefly to output measured variables as analog voltages using a PhidgetsAnalog device with the voltage output configurable as a linear combination of the measured values. The software runs on the Robot Operating System (ROS) and can use any camera or other source that provides a ROS image stream.

For general use, for example, to provide flexibility for precise insect or camera position, each of the head/abdomen/left/right body parts have a set of moveable control points that determine the region of interest. In our experiments, each fly was placed in as close to the same position as possible (e.g., the head handle did not need adjustment); however, sometimes, the size of the fly or small angle differences required us to move the handles slightly for accurate measurement. The regions of interest are in the general form of a sector of a circle in which the spanned angle and inner and outer radii are determined by the control points. The reported measurements per region include angle, radius, intensity, gradient (intensity change per angular or radial unit), and intensity frequency.

For each body part (i.e., region of interest), several tracking techniques are available: area tracking, edge finding, and tip tracking. Although we did not use it for this study, an auxiliary elliptical region may also be monitored (intended to measure the intensity signal in a region or to measure the intensity frequency such as that of a wingbeat).

We used three modes of tracking with Kinefly for this study. The first, “area tracking,” which we used for the head and abdomen, tracks rotational and radial movement using image registration techniques. We also used “edge finding” to track the angular position of the leading wing edges. Last, we used “tip tracking” to detect wing deviation and abdomen length by finding the point in each frame where the body part is visibly farthest from the rotation center. We measured these parameters using three cameras. The first camera was mounted directly below the fly and was used to measure head and abdomen yaw and left and right wingbeat amplitude. Two cameras mounted on the left and right sides of the flies were used to track left and right wing deviation, head tilt, abdomen flexion, and abdomen lengthening.

We enabled background subtraction for each body part individually, with the background updated as a moving average of the image stream with a time constant. Source code and further documentation are provided at https://github.com/ssafarik/Kinefly.

Data analysis and statistics.

We analyzed data using Matlab (MathWorks). For electrophysiology experiments, we acquired data at a sample rate of 10 kHz using Axoscope version 10.2 software. Spikes were detected with custom software that filtered the raw membrane potential, detected peaks, and selected the rapid peaks corresponding to spikes. To detect the smaller-amplitude spikes that occurred during flight and the larger ones typically observed during quiescence, spikes were selected based on an increase in amplitude of least 0.5 mV during flight or 1.2 mV during quiescence within a 40 ms window. For DNOVS1 and DNOVS2, flies that flew at least one trial per rotation stimulus were included in our analysis. We were able to record from DNHS1 cells in four flies and present data from the two flies that flew (with the exception of Figs. 3G and Fig. 4, in which nonflight data from all four DNHS1 cells are plotted). Averages are listed as ± SD about the mean.

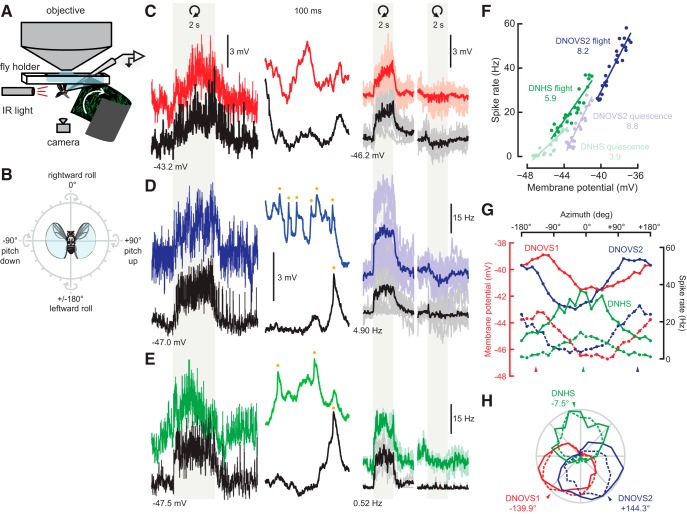

Figure 3.

The three descending neurons are tuned to distinct axes of rotation. A, Schematic of the electrophysiology–behavior preparation (not to scale). B, Icon depicting how rotational stimuli are represented in the present study. Direction of rotation is presented according to the right-hand rule. For instance, rotation at an angle of zero corresponds to roll of the fly down to the right around its longitudinal axis. C, Membrane potential traces from DNOVS1. In the leftmost column, an entire motion stimulus is plotted. Response during quiescence is shown in black and the trace from during flight is shown in red. In the second-most column, 100 ms of raw membrane potential (from the left trace, after motion) is shown. DNOVS1 responds with purely graded changes in membrane potential. The right two columns show average membrane potential responses for DNOVS1 for eight individuals (lighter thin lines) and across flies (thick lines). The light gray region indicates the 2 s when the rotational stimulus was presented. Motion corresponding to clockwise and counterclockwise rotations of the fly at the preferred axis is indicated by the curved arrows. Baseline membrane potentials during quiescence are shown. D, DNOVS2 raw (left two columns) and average (right two columns) responses to motion. Blue indicates responses during flight and black indicates responses during quiescence. Yellow dots indicate spikes in the expanded traces. Averages across and single traces for 11 flies are shown. DNOVS2 produces small spikes on top of graded changes in membrane potential during flight and motion. E, DNHS1 raw and average responses to motion for two flies (same format as C and D). Responses during flight are in green and during quiescence are in black. DNHS1, similar to DNOVS2, produces small spikes, indicated by the yellow dots in the second-most column. The traces in the left column in C, D, and E are all plotted on the same y-scale; traces in the second column of C, D, and E are equal but slightly expanded relative to the left column. F, Average membrane potential versus spike rate during motion for DNOVS2 and DNHS1. DNOVS2 responses during flight and quiescence are plotted in dark and light blue, respectively. DNHS1 responses during flight and quiescence are plotted in dark and light green, respectively. Averages at each azimuthal rotation axis is plotted as a dot. Line indicates least-squares fit for each set of responses. The slope of the least-squares fit for DNOVS2 flight and quiescence data are 8.2 and 8.8 Hz/mV, respectively. The slope of the least-squares fit for DNHS1 flight and quiescent data are 5.9 and 3.9 Hz/mV, respectively. G, Average tuning curves for the three descending neurons. Average responses to motion are shown for the entire range of rotation axes along the x-axis (every 15°) for each cell. DNOVS1 averages are shown in red, DNOVS2 in blue, and DNHS1 in green. The nonspiking DNOVS1 averages are plotted in terms of membrane potential (red y-axis) and DNOVS2 and DNHS1 averages are plotted as spike rates (black y-axis). The solid and dashed lines indicate average tuning responses measured during flight and quiescence, respectively. For DNOVS1 and DNOVS2, averages for flight and quiescence are derived from the same set of flies (n = 8 and n = 11, respectively). For DNHS1, tuning during quiescence was measured in four flies and during flight for two of these four flies. H, Same data as in G but normalized to the maximum response for each neuron during flight and quiescence and plotted in polar coordinates. The arrowhead indicates the peak tuning of each neuron determined by a sine least-squares linear model.

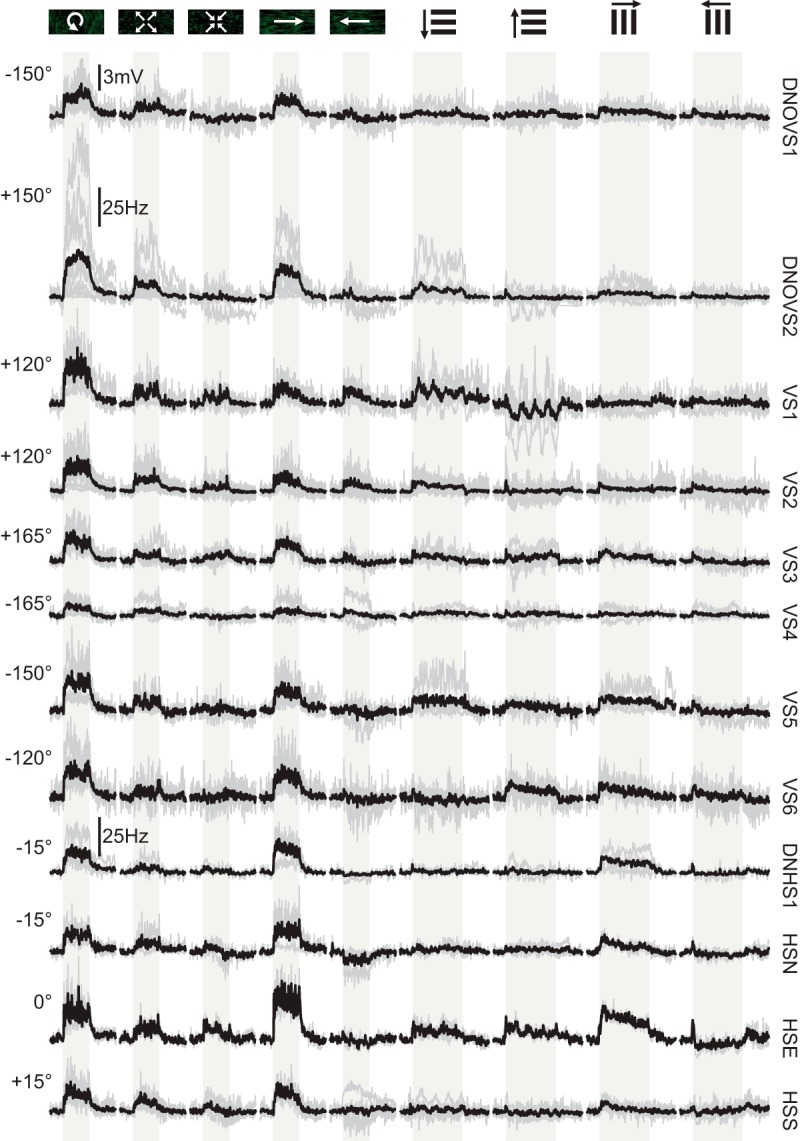

Figure 4.

Physiological responses of all neurons to a suite of motion stimuli during nonflight. Each neuron's responses are plotted in a single row (name indicated to the right of the traces). The icons at the top of each column indicate motion of the visual stimulus and these include rotation in the azimuthal plane at the peak response axis during nonflight (indicated to the left for each neuron), progressive motion, regressive motion, rightward yaw, leftward yaw, 1 Hz downward- and upward- moving sine-wave gratings, and 1 Hz rightward- and leftward- moving sine wave gratings. The stimulus directions are presented relative to the fly's perspective and all recordings were made from cells on the right side of the brain. The light-gray-shaded region indicates when the visual stimulus was in motion (2 s for azimuthal rotation, yaw, and translation and 4 s for 1 Hz vertically and horizontally moving gratings). Gray traces indicate single fly averages and the thick black lines indicate averages across flies. Responses for DNOVS2 and DNHS1 are plotted as spike rates (in Hertz) and all other responses are plotted on the same scale as membrane potential (scale bar on top row). The numbers of flies plotted for each neuron are as follows: DNOVS1, n = 8; DNOVS2, n = 10; VS1, n = 6; VS2, n = 13; VS3, n = 6; VS4, n = 5; VS5, n = 4; VS6, n = 7; DNHS1, n = 4; HSN, n = 3; HSE, n = 2; and HSS, n = 6.

We generated the model of descending neuron output using a linear summation of variable numbers of weighted LPTC responses (see Fig. 6). The model optimized a least-squares fit starting with the single LPTC that generated the smallest residual sum of squares (RSS) value between the descending neuron model and measured responses, followed by the second, third, and so on. We modeled DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 output with VS cells and DNHS1 with HS cells.

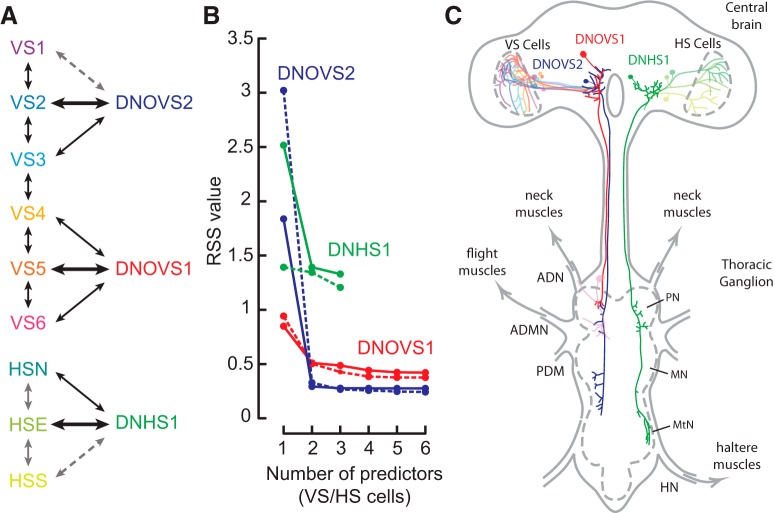

Figure 6.

Model and schematic of visual interneuron and visual descending neuron connectivity. A, Summary of known direct (black arrows), indirect (solid gray arrows), and hypothesized (dashed gray arrows) gap junction connections among VS cells, HS cells, and the three descending neurons. Thicker black arrows indicate the single best LPTC predictor for each descending neuron from the linear model in B. B, Linear prediction model of descending neuron rotation responses built using varying numbers of visual interneuron responses. We model DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 responses (Fig. 3G) as a linear sum of VS cell rotation tuning responses (Fig. 5C). DNHS1 responses (Fig. 3G) are modeled by a linear sum of HS cell responses (Fig. 5C). RSS values for the model built with responses during flight are connected by solid lines, quiescence by the dashed line. Including more than two neurons in each descending neuron's model adds only marginal gains in its predictive quality. C, Schematic diagram of the Drosophila central brain and thoracic ganglion showing the three descending neurons and VS and HS cells. Thoracic nerves associated with flight motor systems (neck, wing, and haltere) are shown and the pro-thoracic, meso-thoracic, and meta-thoracic neuromeres (PN, MN, and MtN, respectively) are labeled.

For behavioral experiments using the Kinefly tracking software, we acquired data at a rate of 1 kHz. Flies that flew for the duration of at least 30 (of 36 possible rotation axes) were included in our analysis, 56 flies in total. We used flies expressing GFP driven by DB331-Gal4 (14 flies) and R94H09-Gal4 (22 flies) and also wild-type flies (Heisenberg Canton-S; 20 flies). No significant behavioral differences were observed among the three strains, so we averaged responses across all three. We averaged responses across all flies (each fly contributed equally to the mean reported). Occasionally, brief tracking errors occurred and appeared as large, rapid changes in voltage and we omitted these from our analysis. We included data from flies in which no more than 1% tracking errors of this type occurred.

To estimate the center of response for each neuron, we determined the maximum response from a nonlinear least-squares sine fit. The fitted function is of the following form: response = p1*sin(angle + p2) + p3, where “angle” is the center of rotation of the visual stimulus and “response” is the average response of the neuron at that angle. We used Matlab's NonLinearModel.fit function to determine the coefficients for each neuron.

Results

Identification of visual descending neurons

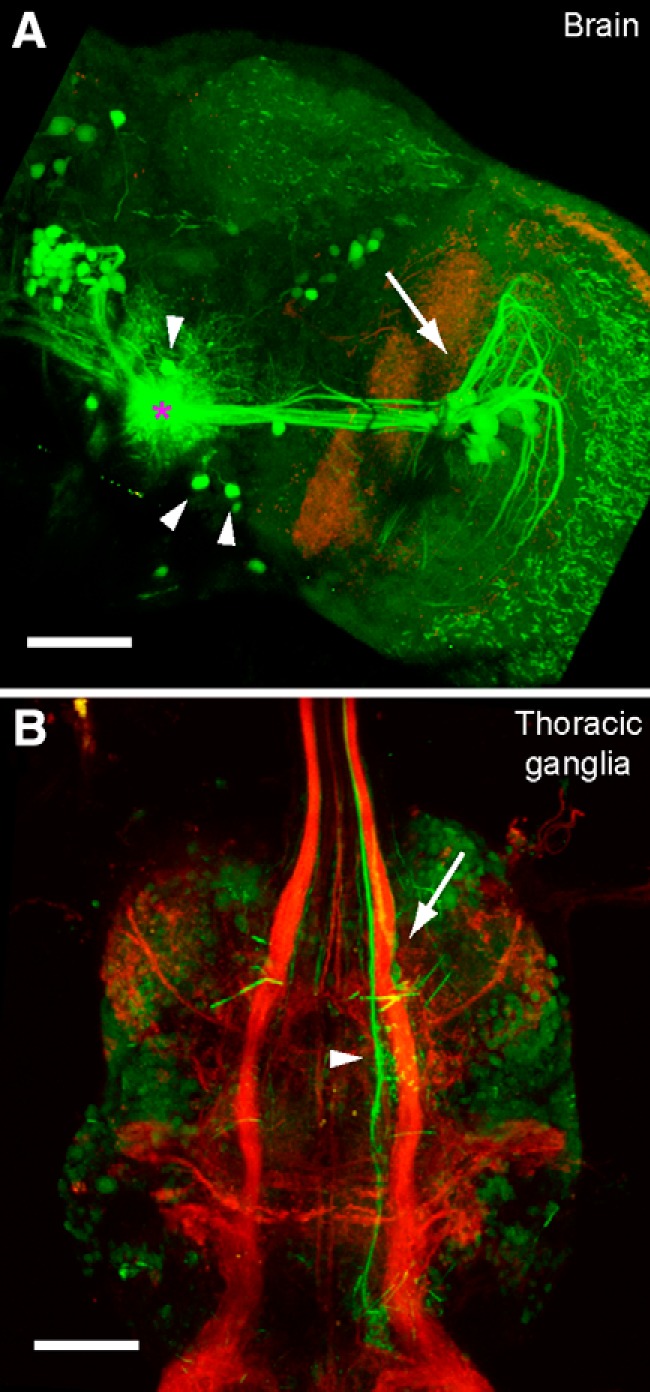

Many higher-order interneurons that encode visual motion terminate in a region of the central brain called the posterior slope (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a, 1985b). We wished to identify downstream neurons from this region that might relay visual information directly or indirectly to motor regions in the thoracic ganglion. As a first strategy to identify these downstream targets, we used PA-GFP (Patterson and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2002) to trace the putative postsynaptic partners of a large class of visual output neurons, the LPTCs. We expressed tdTomato in a subset of LPTCs using the driver line DB331-Gal4 and expressed PA-GFP pan-neuronally using the nSyb-LexA driver line. When we activated a small volume around the output terminals of VS cells, we observed robust activation in the VS cells themselves (Fig. 1A), confirming that we had targeted the output processes of these cells correctly. We also identified many neurons with neurites that overlapped with those of the VS cells, including a small number of descending neurons that project to the thoracic ganglia (Fig. 1B).

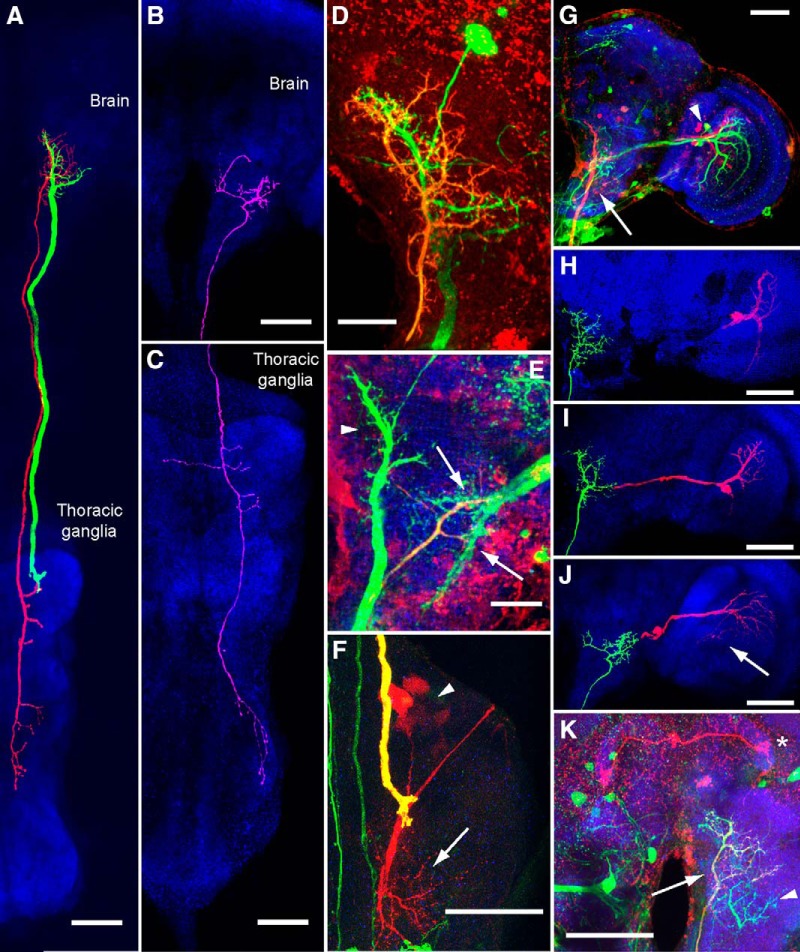

Figure 1.

Photoactivation of visual interneuron outputs. A, GFP signal after photoactivation of PA-GFP in VS cell output terminals (green) in the right hemisphere of the central brain. The left of the image is approximately the midline of the brain. Red signal shows residual tdTomato expression driven by the driver DB331-Gal4 used to target the visual interneurons initially. The approximate center of activation is marked by the pink asterisk. Activation at VS output terminals led to robust activation in the VS cells (arrow points toward cell bodies and dendritic arbors), as well as a number of putative descending neuron cell bodies (arrowheads). B, GFP signal after photoactivation of PA-GFP in the thoracic ganglia in the same brain as in A. Red signal shows tdTomato expression driven by the driver DB331-Gal4 used to target the visual interneurons in the brain initially. A large output process of a descending neuron in the neck motor neuropil (arrow) and a second prominent descending process (arrowhead) are identified. Scale bar, 50 μm in both A and B.

These experiments gave us some confidence that descending neurons downstream of the VS cells exist in Drosophila. Using the results of our PA-GFP experiments as a guide, we searched the Janelia FlyLight collection (Jenett et al., 2012) for driver lines that labeled neurons with processes in the region of the posterior slope where LPTCs terminate. We identified three lines that labeled neurons with input processes in the vicinity of LPTC output terminals: R15C02-Gal4, R20C05-Gal4, and R94H09-Gal4. Subsequent dye fills of the putative downstream neurons revealed three descending neurons with input in the posterior slope (Fig. 2). Based on anatomical (Fig. 2A,D,G, F,K) and physiological (Fig. 3 and see next section) similarities, we tentatively identified two of these descending neurons as the Drosophila analogs of the DNOVS cells described previously in the blowfly: DNOVS1 (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985; Haag, Wertz, and Borst, 2007a) and DNOVS2 (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Wertz et al., 2008). In the posterior slope of the central brain, each of these two neurons has two major branches that form a characteristic y-shape. Biocytin fills of the cells resulted in consistent trans-synaptic labeling of subgroups of VS cells, which is evidence that gap junctions exist between these sets of neurons. Specifically, we observed dye coupling between DNOVS1 and VS4, VS5, and VS6 (Fig. 2G), as well as between DNOVS2 and VS2 (Fig. 2H) and VS3 (Fig. 2I). We also observed one surprising example of a brain in which DNOVS2 was dye coupled to a protocerebral bridge neuron (Fig. 2K). In addition, DNOVS1 terminates in the dorsal region of the prothoracic neuromere, which corresponds to the neck motor region described in previous studies (Power, 1948; Strausfeld and Gronenberg, 1990; Fig. 2A,F and see Fig. 6C) and was strongly dye coupled with what are likely a cluster of frontal neck motor neurons (Fig. 2F and see Fig. 6C; Power, 1948). The axonal diameter of DNOVS1, as measured in the neck connective, is particularly large (4.5 ± 0.64 μm), second only to the giant fiber neuron (5–6 μm; Coggshall et al., 1973; Hengstenberg, 1973). The axonal diameter of DNOVS2, in contrast, is half that size (2.2 ± 0.08 μm). We did not observe any dye coupling between DNOVS2 and any cells in the thoracic ganglion. However, DNOVS2 terminates in the dorsal regions of the pro-thoracic, meso-thoracic, and meta-thoracic neuromeres, which correspond to the neck, wing, and haltere neuropils, respectively, as described previously (Power, 1948; Strausfeld and Gronenberg, 1990; Fig. 2A and see Fig. 6C). The DNOVS2 axon travels along the median tract of the dorsal cervical fasciculus (Power, 1948; Boerner and Duch, 2010). Both DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 share similar output regions with those observed in the blowfly (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985), further evidence that the neurons in these two species are homologous.

Figure 2.

Anatomy of the descending neurons and gap junction-coupled synaptic partners. A, DNOVS1 (green) and DNOVS2 (red) are traced in the same brain and shown with an anti-nc82 neuropil stain (blue). We traced GFP expression in DNOVS1 and an intracellular fill in DNOVS2 (biocytin later conjugated to an Alexa Fluor dye). The neuropil signal is a maximum-intensity projection. B, DNHS1 (pink) was traced using an intracellular fill and is shown against a neuropil stain in the same brain (blue). C, Processes of DNHS1 traced in the thoracic ganglia indicate putative output processes in neck and haltere motor regions. D, Magnified maximum intensity projection of DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 processes in the brain. GFP expression in DNOVS1 appears green. The processes of DNOVS2, which are also labeled by GFP, are also labeled with an Alexa Fluor dye conjugated to biocytin (red; overlap appears yellow-orange). The cell body of DNOVS2 was extracted during removal of the recording electrode, but that of DNOVS1 remains. E, DNHS1 processes overlap with HS terminals (arrows). DNHS1 and HS cells express GFP (green) and DNHS1 is also labeled with an intracellular biocytin fill (red; overlap appears yellow-orange). DNOVS1 is also labeled by this driver line and appears in this image (arrowhead). F, DNOVS1 output terminals in the neck motor region. DNOVS1 is labeled both by GFP (green) and an intracellular dye fill (red) and appears yellow. Dye-coupled synaptic partners with DNOVS1, the frontal neck motor neurons, appear in red (dendrites are indicated by the arrow and cell bodies by the arrowhead). G, DNOVS1 and dye-coupled synaptic partners VS cells 4–6 are labeled with a biocytin fill (red). DNOVS1's axon is indicated by the arrow and cell bodies of VS 4–6 by the arrowhead. GFP expression is shown in green and anti-nc82 neuropil stain is in blue. VS 1–3 are not dye coupled to DNOVS1, but are also labeled by this Gal4-driver line (green) and appear next to the red VS 4–6 cell dendrites. H, DNOVS2 (green) is dye coupled to VS2 (red). Both neurons were traced using the same biocytin stain after filling DNOVS2, but are colored differently. Neuropil appears blue. I, DNOVS2 (green) is dye coupled to VS3 (red). Neuropil appears blue. J, DNHS1 (green) is dye coupled to HSN and HSE (red; HSE is faintly filled in this image and marked with an arrow). Neuropil stain appears blue. K, DNOVS2 (axon indicated by arrow) is labeled by GFP (green) and filled with biocytin (red signal; overlap with GFP signal results in yellow appearance of DNOVS2). A dye-coupled neuron in the protocerebral bridge appears red (asterisk). DNHS1 is also labeled by GFP in this driver line (green; arrowhead). Scale bars in D and E are 20 μm; all others are 50 μm. We used the following driver lines to label neurons in this figure: for A, D, and K: 94H09-Gal4; for B, C, and F: R15C02-Gal4; and for E and G: R20C05-Gal4. In all figures, the brain is oriented so anterior is upward.

The third visual descending neuron that we identified is shown in Figure 2, B and C. This cell also has dendrites in the posterior slope; however, they are slightly deeper and more ventral than those of DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 and colocalize with HS cell terminals (Fig. 2E). We observed dye coupling between this neuron and two of the HS cells, HSN and HSE (Fig. 2J). To our knowledge, this neuron has not been described previously and, because of its physiological properties (Fig. 3 and see next section), we named it DNHS1 (descending neuron of the horizontal system 1). The axon of DNHS1 runs along the intermediate tract of the dorsal cervical fasciculus (Power, 1948; Boerner and Duch, 2010) and its output terminals project to dorsal regions of the pro-thoracic and meta-thoracic neuromeres, corresponding to the neck and haltere motor neuropils, respectively (Power, 1948; Strausfeld and Gronenberg, 1990; Fig. 2B and see Fig. 6C). Its diameter is slightly larger than that of DNOVS2 (2.5 ± 0.84 μm). To summarize, the three descending neurons appear to receive input from three distinct sets of HS and VS cells and project to distinct regions of the thoracic ganglia. We observed labeling of the three descending neurons and their putative presynaptic inputs in the following driver lines: R20C05-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2, DNHS1, VS1–6); R94H09-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2); and R15C02-Gal4 (DNOVS1, DNOVS2, DNHS1, HSN, HSE, HSS).

We did not observe any dye coupling between the three descending neurons and ocellar interneurons, which are known inputs to the blowfly DNOVS neurons (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Haag et al., 2007). It is possible that ocellar inputs to these neurons do not exist in Drosophila; however, the dorsal branch of DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 in Drosophila share a similar structure to the dorsal branch that receives input from ocellar interneurons in the analogous blowfly neurons (Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985; Haag et al., 2007). It is thus more likely that either biocytin did not travel through gap junctions between the descending neurons and ocellar interneurons in any of our preparations or that the inputs from ocellar interneurons are mediated via chemical synapses.

Descending neurons encode distinct rotation axes

Because the descending neurons receive input from LPTCs, which encode patterns of optic flow that correspond to self-motion (Hausen, 1984; Krapp and Hengstenberg, 1996; Krapp et al., 1998; Karmeier et al., 2003), we investigated whether the descending neurons would similarly encode patterns of optic flow produced by ego motion. To measure the physiological responses of each neuron under conditions of flight and quiescence (Fig. 3A), we attached each fly to a holder that permits access to the brain for electrophysiological recordings (Maimon et al., 2010; Suver et al., 2012). We presented the fly with moving star-field patterns of optic flow that mimicked ego motion, including rotational stimuli centered at equally spaced positions in the azimuthal plane (every 15°). We found that the descending neurons were tuned to rotations around three approximately orthogonal axes (Fig. 3). Examples of whole-cell recordings from each of the three cells are shown in Figure 3, C–E. We found no evidence of action potentials in the large-diameter DNOVS1 cell, which responded to motion with graded changes in membrane potential, whereas DNOVS2 and DNHS1 both exhibited small spikes (∼1–5 mV) riding on slower changes in membrane potential. Presumably, the small amplitude of the action potentials was due to filtering by the passive soma and the narrow neurite connecting it to the dendrite. We found a quite linear relationship between the membrane potential and spike rate for both DNOVS2 and DNHS1 (Fig. 3F). The spike rate of DNOVS2 and DNHS1 increased relatively linearly along with membrane potential and a few millivolt increase was accompanied by an increase in spike rate of a few tens of Hz (Fig. 3F).

The response of each neuron was tuned to the sine of the angular position of the visual rotation axis in the azimuthal plane, although the phase of this tuning differed among the three cells (Fig. 3G,H). We estimated peak rotational axes for each cell by fitting a sine function to the average responses as a function of azimuthal angle. In flying flies, DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 neurons in the right hemisphere responded maximally to rotational stimuli that correspond to the fly rotating counterclockwise about azimuthal axes positioned at −139.9° and +144.3° relative to the fly's midline, respectively (Fig. 3C,D,G,H; r2 values of sine fits to the mean response are 0.94 and 0.98, respectively). Rotation in the opposite direction elicited either small inhibitory responses or no responses in the neurons. During quiescence, the maximal responses of DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 were centered at slightly more medial rotational axes (−143.9° and +152.9°, respectively), but these changes were not statistically significant (Student's t test, α > 0.05).

DNHS1 responded strongly to rotational stimuli and showed a preferred azimuthal tuning at −7.5° during flight (r2 value of the cosine fit is 0.93), corresponding to roll down toward the ipsilateral side (Fig. 3E,G,H). For all three neurons, we also measured the responses to moving star-field patterns corresponding to yaw rotation (left and right), forward translation, and rearward translation. We also presented vertically and horizontally moving gratings at a temporal frequency of 1 Hz. Although DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 responded most strongly to rotation around their preferred axes in the azimuthal plane, DNHS1 responded more strongly to motion corresponding to pure yaw (Fig. 4). This result is consistent with our evidence that DNHS1 is electrically coupled to at least two HS cells. Although we did not probe this cell's responses to different rotational axes in the sagittal plane, our results suggest that the DNHS1 cell is probably maximally tuned to a rotation axis oriented somewhere between the roll and yaw axes. No neuron in this study responded more strongly to translation than to azimuthal rotation or yaw stimuli (Fig. 4).

In addition to differences in directional tuning, we also noted different dynamics in the three cells. DNOVS1 responded to motion with a slow ramp in activity during the stimulus epoch, whereas DNOVS2 and DNHS1 reached a maximal response more quickly (Fig. 3C–E). The cells also exhibited a slow return to baseline after the offset of the visual stimulus. The persistence of activity after the cessation of motion suggests the presence of a leaky integrator residing either in the cells themselves or in their presynaptic pathways. This observation is consistent with a recent study (Schnell et al., 2014) showing that the slow calcium dynamics within the output terminals of HS cells might provide a mechanism to explain the existence of temporal integration in behavioral responses to large-field visual motion. Last, all three neurons typically exhibited an increase in baseline activity during flight (DNOVS1: 4.7 ± 1.6 mV; DNOVS2: 24.5 ± 13.9 Hz; and DNHS1: 13.6 ± 5.0 Hz).

Small sets of VS and HS cells can explain tuning of descending interneurons

The dye-coupling results and tuning of the three descending neurons suggest that their behavior might result from the combination of tuning properties of their putative presynaptic inputs. We measured the responses of the VS and HS cells and used these responses to create a simple predictive model of the tuning properties of each of the descending neurons. Although the VS and HS cells have all been studied in Drosophila using simple sinusoidal gratings (Joesch et al., 2008; Schnell et al., 2010), their tuning to rotatory stimuli in the azimuthal plane was not known previously. To aid in targeting VS and HS cells, we drove GFP expression using the following driver lines: DB331-Gal4, R15C02-Gal4, and R20C05-Gal4. Although we did not observe any fluorescence in VS and HS cells using the R94H09-Gal4 driver, we occasionally targeted these cell types in this background based on size and position and verified cell identity later after filling the neuron.

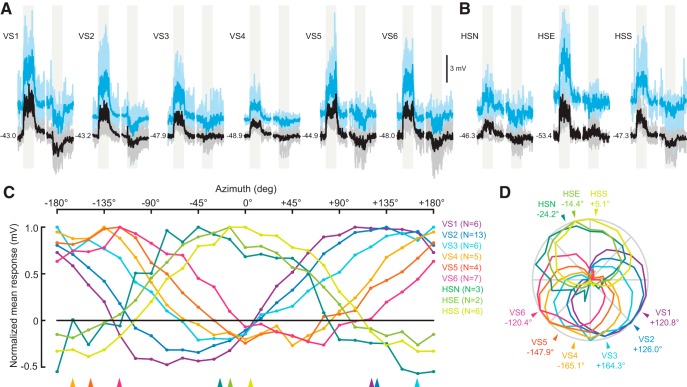

We presented flies with the same star-field patterns used to characterize the descending neurons. Average response traces for VS and HS cells at the maximum rotation angle are shown in Figure 5, A and B, respectively. VS cells responded most strongly to rotation axes distributed relatively evenly between +120° and −120°, with VS1 at one extreme (+120.8°) and VS6 at the other (−120.4°) (Fig. 5). The HS cells also responded strongly to rotation in the azimuthal plane and all three neurons exhibited relatively similar tuning. During flight, the HS cells responded maximally to rotation about an azimuthal axis that was close to pure roll down on the ipsilateral side (HSN: −24.2°; HSE: −14.4°; HSS: +5.1°). As expected, all three cells in Drosophila responded strongly to pure yaw motion (Fig. 4), in agreement with responses of homologous cells in both fruit flies and blowflies (Hausen, 1982a, 1982b; Krapp et al., 2001; Schnell et al., 2010). The responses of HSE were stronger than those of HSN or HSS, presumably due to a closer match between the region of the retina that our display covers and the spatial tuning properties of the neuron (Hausen, 1982b; Schnell et al., 2010).

Figure 5.

Rotation tuning of VS and HS cells. A, Membrane potential responses of the six VS cells to rotational stimuli centered at the cell's preferred axis during flight. Responses to motion corresponding to clockwise (preferred) rotation of the fly are plotted followed by responses to counterclockwise (nonpreferred) rotation. The light-gray-shaded regions indicate when the 2 s rotational visual stimulus was in motion. Averages across flies and for single flies are plotted as thick and (lighter) thin lines, respectively. Black traces show responses during quiescence and responses during flight are plotted in blue. Baseline membrane potential during quiescence is indicated. B, Membrane potential responses of the three HS cells to azimuthal rotational stimuli. Averages across flies and for single flies are plotted as thick and (lighter) thin lines, respectively. The gray-shaded regions indicate when the 2 s rotational visual stimulus was in motion. B has same scale as A. C, Rotation tuning curves during flight for the VS and HS cells across the entire range of azimuthal rotation axes measured (every 15°). Each neuron is plotted in a different color. This color, and the number of flies contributing to the average for each cell, is indicated in the legend to the right of the tuning curves. Normalized mean responses to rotational stimuli are plotted. D, Same data as in C, normalized and plotted in polar coordinates. The arrowheads indicate the peak tuning of each neuron determined by a sine least-squares linear model.

As shown in Figure 5, C and D, three clusters emerge when the azimuthal rotation tuning curves for VS and HS cells are compared. VS cells 1–3 all respond most strongly to a rotational axis near +140°, whereas VS cells 4–6 are tuned to the bilaterally symmetric axis at −140°. Although the HS cells are known to encode rotation about the yaw axis, they also respond to roll within the azimuthal plane (0°). Therefore, the rotational axis that elicits the peak response in HS cells must lie in the sagittal plane with components of both the yaw and roll axes. The three tuning clusters of the LPTCs in the azimuthal plane correspond approximately to directional sensitivity of the three descending interneurons to which they are coupled: DNOVS1, DNOVS2, and DNHS1 (Fig. 2).

Based on our anatomical and physiological evidence, we propose the connectivity circuit shown in Figure 6A. Evidence suggests that the VS cells are coupled directly to their immediate VS neighbors via gap junctions and the HS cells are thought to be at least indirectly coupled to one another in Calliphora (Haag and Borst, 2005; Fig. 6A). To investigate the putative connectivity pattern that might explain the rotational tuning of the descending neurons, we created a linear model in which the responses of the descending neurons were predicted by variable combinations of LPTC output (Fig. 6B). We predicted the responses of DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 using VS cells and those of DNHS1 using HS cells. Figure 6B shows the RSS values that result from a model in which we predicted each descending neuron's rotation tuning curve using an increasing number of LPTCs. Beyond two neurons, relatively little predictive power is gained by including additional inputs. This result is expected, given that tuning curves of all LPTCs were approximately sinusoidal as a function of azimuthal angle. Therefore, any two cells would constitute a basis set from which any arbitrary tuning curve could be constructed. It is most likely, however, that the descending cells derived their tuning from the visual interneurons with responses that they match most closely. The three neurons that best predicted the rotation response of DNOVS1 were VS5, VS6, and VS4, in descending order. Similarly, the responses of DNOVS2 were best predicted by VS2, VS3, and VS1, whereas those of DNHS1 were predicted by HSE, HSS, and then HSN. We found anatomical evidence for, at most, three gap junction LPTC inputs to each descending neuron type (Fig. 2, schematized in Fig. 6C), in agreement with our model results.

Responses of the descending neurons are correlated with distinct motor programs

The DNOVS1, DNOVS2, and DNHS1 cells terminate in the pro-thoracic, meso-thoracic, and meta-thoracic neuropils, respectively (Figs. 2, 6C), suggesting that they may play distinct roles in motor output. The most direct way of ascribing function to the three cells would be to activate or silence them selectively during flight. However, as also found in a recent study on the giant fiber neuron (Von Reyn et al., 2014), we could not pass enough current through our recording electrode on the cell body to influence the output of the neuron and none of our driver lines was specific enough to permit selective silencing or optogenetic activation. Therefore, we could not assess the function of the neurons directly via test of necessity and sufficiency. However, to gain some insight into the motor behaviors that the three cells might play, we created a machine vision-tracking system, which we call Kinefly, to track the motion of the head, wings, and abdomen simultaneously during tethered flight. We performed this behavioral analysis as a hypothesis testing framework, not as a means to identify causal relationships. Our goal was to investigate how the flight motor program, which includes motion of the wings, haltere, head, and abdomen, might be associated with the thoracic neuropil regions to which the three descending neurons project. Using the Kinefly system, we characterized behavioral responses to the same suite of self-motion stimuli that we used in our electrophysiology experiments. Figure 7 shows the average responses of each body measureement.

Figure 7.

Behavioral responses to rotational stimuli. A, Right wing amplitude. Below the fly icon, the peak response trace to motion (determined by a sine least-squares linear fit to the response across all rotation axes) and to rotation in the opposite direction are shown. Thick traces indicate the average response of the right wing amplitude across flies and the gray region shows SEM. The thin black bar indicates when the 2 s rotational visual stimulus was presented. On the lower right, the average responses to azimuthal rotational motion across all axes (every 15°) are plotted. Above, the same data are plotted in a normalized polar histogram and the peak axis of rotation is indicated by the arrowhead. The average descending neuron tuning responses are plotted in light colors behind the behavioral tuning curve for comparison. All data are plotted using the same right-hand rule convention as Figures 3 and 5. B, Left wing amplitude, plotted in the same manner as in A. C, Right wing deviation. Deviation of the leading tip of the wing is indicated by the red dot. D, Left wing deviation. E, Head yaw. Peak azimuthal rotation responses (“max” and “min”) are plotted to the left of responses to pure yaw motion (visual motion corresponding to the fly yawing to the left and right are indicated by arrows). F, Abdomen ruddering. Yaw responses are plotted to the right of maximum azimuthal rotation responses. G, Head pitch. H, Abdomen flexion. Note that the vertical scale for E through H is different from that for A through D. Averages for A–H were obtained in the same 56 flies for all traces. r2 values for the sine fits in A–H are 0.94, 0.95, 0.93, 0.95, 0.73, 0.59, 0.61, and 0.60, respectively.

In agreement with previous work (Dickinson, 1999), we found that the right and left wing amplitudes are maximal at angles somewhere between pure pitch and roll down to the right and down to the left, respectively (Fig. 7A,B). The tuning of wing tip deviation (Fig. 7C,D) was tuned similarly to wing amplitude, but is maximal slightly closer to pure pitch. DNOVS1 was most correlated with an increase in contralateral wing amplitude and deviation. We observed small abdomen movements similar to those described previously in Drosophila (Zanker, 1988; Bartussek and Lehmann, 2016). As expected, we found that head yaw and lateral abdomen ruddering were larger when the fly was presented with a pure yaw stimulus compared with azimuthal rotation (Fig. 7E,F). Abdomen movements were approximately opposite from the head during ruddering; that is, the head follows the direction of movement and the abdomen opposes it. Head pitch movements were maximal when the visual motion corresponded to downward pitch (Fig. 7G) and downward abdominal flexion was approximately opposite (Fig. 7H). Finally, the abdomen tended to lift upward in response to upward frontal visual stimuli (corresponding to the fly pitching downward).

Discussion

We have identified three pairs of descending neurons that integrate input from an array of visual interneurons in Drosophila. DNOVS1 and DNOVS2 are likely the homologs of neurons in larger flies (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Haag et al., 2007; Wertz et al., 2008), whereas DNHS1 is a previously undescribed cell. We measured the tuning properties of these neurons during flight and found that they encode three distinct axes of rotation (Fig. 3), which are predicted by a linear summation of the responses of presynaptic VS and HS cells (Figs. 5, 6). The descending neurons project to nonoverlapping regions of dorsal neuropil within the ventral nerve cord (VNC) (Figs. 2, 6C), suggesting that they control different motor programs associated with flight. Indeed, we found that the neurons were most strongly correlated with various body movements in response to visual motion, although this by no means indicates a causal relationship (Fig. 7).

The large axonal diameter and abrupt terminals of DNOVS1 in the neck neuropil (Figs. 2A,F, 6C) suggest that this cell is specialized for regulating rapid movements of the head. Neck motor neurons innervate 21 pairs of neck muscles (Milde et al., 1987) and their activation elicits rotations of the head about specific axes (Gilbert et al., 1995). The neck motor neurons respond strongly to visual motion (Milde et al., 1987; Gilbert et al., 1995; Huston and Krapp, 2008; Kauer et al., 2015). In Calliphora, the haltere nerve innervates the neck motor neuropil (Chan and Dickinson, 1996) and contralateral haltere interneurons are electrically coupled with both neck motor neurons and DNOVS1 (Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985). This convergence of visual and mechanosensory feedback could enable precise compensatory movements of the head to reduce motion blur (Hateren and Schilstra, 1999). Although the halteres provide self-motion information more rapidly than the visual system (Sherman and Dickinson, 2003, 2004), DNOVS1 likely represents the fastest pathway by which visual information influences the fly's motor responses.

DNOVS2 and DNHS1 also have terminals in the neck motor region (Figs. 2A,C, 6C), although they do not appear to be electrically coupled to any motor neurons. Unlike DNOVS1, however, these cells also project to the wing and haltere neuropils. Visual input to the haltere motor system has been documented physiologically in blowflies (Chan et al., 1998) and behaviorally in Drosophila (Mureli and Fox, 2015; Bartussek and Lehmann, 2016), a phenomenon that might be mediated by DNHS1. The tuning curves for both head yaw and abdominal ruddering were quite similar to that of DNHS1 (Fig. 7E,F), a correlation that should be explored in future studies.

Drosophila exhibit flight patterns in which straight sequences are interspersed with rapid stereotyped turns called body saccades (Buelthoff et al., 1980; Tammero and Dickinson, 2002). Flies execute saccades by generating a rapid banked turn in which they first roll to reorient their flight force and then counter roll to regain an upright pose. In Drosophila hydei, these roll and counter-roll axes are oriented at ∼36° and 8°, respectively, relative to the longitudinal axis of the fly (Muijres et al., 2015). The orientation of the initial roll axis is remarkably similar to the axis that elicits a peak response in the DNOVS2 cell (−35.7°), suggesting a possible role for this neuron during body saccades.

The representation of self-motion appears to be similar between Drosophila and blowflies despite the fact that fruit flies possess approximately half the number of VS cells (Scott et al., 2002). Theoretically, two cells would be sufficient to encode any arbitrary rotation in the azimuthal plane. However, the receptive fields of the VS cells cover different sectors of the visual world and no two cells extend over the entire field of view. Therefore, more than two cells are required to accurately encode rotation in a sparse visual scene (Cuntz et al., 2007). In addition, the large number of VS cells likely increases the speed and accuracy of self-motion estimation (Karmeier et al., 2005; Taylor and Krapp, 2007). The reduction in the number of VS cells in Drosophila may reflect a much lower number of ommatidia covering the azimuth compared with larger flies. We do not know, however, if the reduced number of VS cells translates into a smaller number of downstream interneurons. We identified two descending neurons downstream of the VS cells in this study, whereas four have been described in blowflies (Strausfeld, 1984; Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1985a; Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985; Gronenberg and Strausfeld, 1990). However, it is premature to draw conclusions until more comprehensive maps of the descending neurons have been compiled for both species.

We found that the visually evoked responses of LPTCs during flight were, on average, a few millivolts higher than during quiescence (Fig. 5), consistent with prior studies (Chiappe et al., 2010; Maimon et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2011; Suver et al., 2012). In contrast, we observed much more substantial increases in the spike rate response of DNOVS2 and DNHS1 to visual motion during flight (Fig. 3F), which suggests that the relatively small flight-dependent increases observed in LPTCs are amplified in the descending neurons. With the exception of VS2, none of the descending interneurons or LPTCs displayed a statistically significant shift in their orientation tuning during flight compared with quiescence (Figs. 3, 5; p > 0.01, paired t test).

Collectively, the three cells that we described encode body rotation around three approximately orthogonal axes (two in the azimuthal plane and one in the sagittal plane). Therefore, the projections of the three cells in the VNC might constitute a map from which any arbitrary rotation could be reconstructed. For example, all three descending neurons that we characterized project to the neck neuropil, where local circuits could use the map to compute any arbitrary rotation. In general, this representation scheme would be analogous to the vestibulocerebellum system in rabbits, in which distinct classes of visually sensitive neurons respond to three axes of rotation and translation (Graf et al., 1988; Leonard et al., 1988) oriented at 45° and 135° on the azimuth and the vertical axis. Pigeons possess a similar system, with neurons in the accessory optic system and vestibulocerebellum encoding translation and rotation (Wylie and Frost, 1990, 1993; Wylie et al., 1993, 1998). The orientation of the three axes encoded in the vestibulocerebellum is quite similar to those encoded by the descending neurons in Drosophila; two cells are tuned to rotation on either side of the midline and one is tuned to yaw. The three axes that we identified in this study may not be the only ones encoded by descending neurons, but the similarities between mammals and flies suggest that animals may use a simple encoding scheme that avoids redundancy.

An alternate interpretation of these descending neurons is that they do not constitute a general map of body rotation, but rather are simply elements in parallel pathways that control distinct sensory motor reflexes. In this view, the outputs of the three cells may never be combined by downstream circuits to calculate an arbitrary angle of body rotation, but each cell may drive motor reflexes that rely solely on estimates of rotation about the individual axes of rotation. The fact that the projection patterns of the three cells are somewhat distinct (e.g., DNOVS1 only projects to the first thoracic neuropil and DNHS1 skips the second thoracic neuropil) supports this view. However, it is possible that the information conveyed by the three cells is functionally combined via their synergistic effects on distinct motor reflexes. For example, a reflex mediated by DNHS1 on the haltere motor system might combine with the effects of a reflex mediated by DNOVS2 on the wing motor system that would be behaviorally appropriate for a compensatory reflex regulating body motion about an axis not encoded directly by the two cells. In addition, a combination of these two encoding schemes might be implemented in which some systems (e.g., the neck motor system) compute arbitrary rotation angles from the three neurons and others (e.g., the wing motor system) rely on the direct influence of only one rotation axis and possibly indirect action from others.

Our study reveals the neural circuitry responsible for encoding rotation along three body axes during flight in Drosophila. The descending interneurons that we characterized are involved in the transformation from visual to motor output and this takes place in as few as six synapses, making it a relatively tractable circuit. In this system, behaviorally relevant visual information is delivered to multiple motor systems and provides a basis for further investigations of cellular mechanisms of sensorimotor processing in a behaving animal.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–National Institutes of Health (Grant U01NS090514 to M.H.D.) and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (M.H.D.). We thank Anne Sustar for assistance with fly stocks; Allan Wong for guidance with the photoactivatible GFP technique; Gwyneth Card and Shigehiro Namiki for useful discussions about the descending interneurons; and Katherine Nagel and Peter Weir for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bartussek J, Lehmann FO. Proprioceptive feedback determines visuomotor gain in Drosophila. R Soc Open Sci. 2016;3:150562. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner J, Duch C. Average shape standard atlas for the adult Drosophila ventral nerve cord. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:2437–2455. doi: 10.1002/cne.22346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelthoff H, Poggio T, Christian W. 3-D analysis of the flight trajectories of flies (Drosophila melanogaster) Z Naturforsch C. 1980;35:811–815. [Google Scholar]

- Chan WP, Dickinson MH. Position-specific central projections of mechanosensory neurons on the haltere of the blow fly, Calliphora vicina. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:405–418. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960603)369:3<405::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WP, Prete F, Dickinson MH. Visual input to the efferent control system of a fly's ‘gyroscope’. Science. 1998;280:289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappe ME, Seelig JD, Reiser MB, Jayaraman V. Walking modulates speed sensitivity in Drosophila motion vision. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1470–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggshall JC, Boschek CB, Buchner SM. Preliminary investigations on a pair of giant fibers in the central nervous system of dipteran flies. Z Naturforsch C. 1973;28:783–784b. [Google Scholar]

- Cuntz H, Haag J, Forstner F, Segev I, Borst A. Robust coding of flow-field parameters by axo-axonal gap junctions between fly visual interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10229–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703697104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson MH. Haltere-mediated equilibrium reflexes of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:903–916. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, Gronenberg W, Strausfeld NJ. Oculomotor control in Calliphorid flies: Head movements during activation and inhibition of neck motor neurons corroborate neuroanatomical predictions. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:285–297. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf W, Simpson JI, Leonard CS. Spatial organization of visual messages of the rabbit's cerebellar flocculus. II. Complex and simple spike responses of Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:2091–2121. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronenberg W, Strausfeld NJ. Descending neurons supplying the neck and flight motor of Diptera: physiological and anatomical characteristics. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:973–991. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag J, Borst A. Dye-coupling visualizes networks of large-field motion-sensitive neurons in the fly. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2005;191:445–454. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag J, Wertz A, Borst A. Integration of lobula plate output signals by DNOVS1, an identified premotor descending neuron. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1992–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4393-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hateren JH, Schilstra C. Blowfly flight and optic flow. II. Head movements during flight. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1481–1490. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.11.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausen K. Motion sensitive interneurons in the optomotor system of the fly. I. The horizontal cells: structure and signals. Biol Cybern. 1982a;45:143–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00335241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausen K. Motion sensitive interneurons in the optomotor system of the fly. II. The horizontal cells: receptive field organization and response characteristics. Biol Cybern. 1982b;46:67–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00335352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hausen K. The lobula-complex of the fly: structure, function and significance in visual behaviour. In: Ali MA, editor. Photoreception and vision in invertebrates. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 523–559. [Google Scholar]

- Hengstenberg R. The effect of pattern movement on the impulse activity of the cervical connective of Drosophila melanogaster. Z. Naturforsch. 1973;28:593–596. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-9-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston SJ, Krapp HG. Visuomotor transformation in the fly gaze stabilization system. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A, et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2012;2:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joesch M, Plett J, Borst A, Reiff DF. Response properties of motion-sensitive visual interneurons in the lobula plate of Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2008;18:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SN, Borst A, Haag J. Flight activity alters velocity tuning of fly motion-sensitive neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9231–9237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1138-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmeier K, Krapp HG, Egelhaaf M. Robustness of the tuning of fly visual interneurons to rotatory optic flow. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1626–1634. doi: 10.1152/jn.00234.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmeier K, Krapp HG, Egelhaaf M. Population coding of self-motion: applying bayesian analysis to a population of visual interneurons in the fly. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2182–2194. doi: 10.1152/jn.00278.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer I, Borst A, Haag J. Complementary motion tuning in frontal nerve motor neurons of the blowfly. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2015;201:411–426. doi: 10.1007/s00359-015-0980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp HG, Hengstenberg R. Estimation of self-motion by optic flow processing in single visual interneurons. Nature. 1996;384:463–466. doi: 10.1038/384463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp HG, Hengstenberg B, Hengstenberg R. Dendritic structure and receptive-field organization of optic flow processing interneurons in the fly. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1902–1917. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp HG, Hengstenberg R, Egelhaaf M. Binocular contributions to optic flow processing in the fly visual system. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:724–734. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CS, Simpson JI, Graf W. Spatial organization of visual messages of the rabbit's cerebellar flocculus. I. Typology of inferior olive neurons of the dorsal cap of Kooy. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:2073–2090. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longair MH, Baker DA, Armstrong JD. Simple Neurite Tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2453–2454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimon G, Straw AD, Dickinson MH. Active flight increases the gain of visual motion processing in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nn.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masino T, Knudsen EI. Horizontal and vertical components of head movement are controlled by distinct neural circuits in the barn owl. Nature. 1990;345:434–437. doi: 10.1038/345434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde JJ, Seyan HS, Strausfeld NJ. The neck motor system of the fly Calliphora erythrocephala II. Sensory organization. J Comp Physiol A. 1987;160:225–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00609728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muijres FT, Elzinga MJ, Iwasaki NA, Dickinson MH. Body saccades of Drosophila consist of stereotyped banked turns. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:864–875. doi: 10.1242/jeb.114280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mureli S, Fox JL. Haltere mechanosensory influence on tethered flight behavior in Drosophila. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:2528–2537. doi: 10.1242/jeb.121863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A photoactivatable GFP for selective photolabeling of proteins and cells. Science. 2002;297:1873–1977. doi: 10.1126/science.1074952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer BD, Truman JW, Rubin GM. Using translational enhancers to increase transgene expression in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6626–6631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204520109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power ME. The thoracico-abdominal nervous system of an adult insect, Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1948;88:347–409. doi: 10.1002/cne.900880303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser MB, Dickinson MH. A modular display system for insect behavioral neuroscience. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;167:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell B, Joesch M, Forstner F, Raghu SV, Otsuna H, Ito K, Borst A, Reiff DF. Processing of horizontal optic flow in three visual interneurons of the Drosophila brain. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:1646–1657. doi: 10.1152/jn.00950.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell B, Weir PT, Roth E, Fairhall AL, Dickinson MH. Cellular mechanisms for integral feedback in visually guided behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5700–5705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400698111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott EK, Raabe T, Luo L. Structure of the vertical and horizontal system neurons of the lobula plate in Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:470–481. doi: 10.1002/cne.10467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Dickinson MH. A comparison of visual and haltere-mediated equilibrium reflexes in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:295–302. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Dickinson MH. Summation of visual and mechanosensory feedback in Drosophila flight control. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:133–142. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ. Functional neuroanatomy of the blowfly's visual system. In: Ali MA, editor. Photoreception and vision in invertebrates. Vol 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 483–522. [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ. Structural organization of male-specific visual neurons in calliphorid optic lobes. J Comp Physiol A. 1991;169:379–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00197652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ, Bassemir UK. Lobula plate and ocellar interneurons converge onto a cluster of descending neurons leading to neck and leg motor neuropil in Calliphora erythrocephala. Cell Tiss Res. 1985a;240:617–640. doi: 10.1007/BF00216351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ, Bassemir UK. The organization of giant horizontal-motion-sensitive neurons and their synaptic relationships in the lateral deutocerebrum of Calliphora erythrocephala and Musca domestica. Cell Tiss Res. 1985b;242:531–550. [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ, Gronenberg W. Descending neurons supplying the neck and flight motor of Diptera: organization and neuroanatomical relationships with visual pathways. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:954–972. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld NJ, Seyan HS. Convergence of visual, haltere, and prosternal inputs at neck motor neurons of Calliphora erythrocephala. Cell Tiss Res. 1985;240:601–615. doi: 10.1007/BF00216350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suver MP, Mamiya A, Dickinson MH. Octopamine neurons mediate flight-induced modulation of visual processing in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2294–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammero LF, Dickinson MH. The influence of visual landscape on the free flight behavior of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:327–343. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GK, Krapp HG. Sensory systems and flight stability: what do insects measure and why? Adv Insect Physiol. 2007;34:231–316. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2806(07)34005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Reyn CR, Breads P, Peek MY, Zheng GZ, Williamson WR, Yee AL, Leonardo A, Card GM. A spike-timing mechanism for action selection. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:962–970. doi: 10.1038/nn.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir PT, Dickinson MH. Functional divisions for visual processing in the central brain of flying Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E5523–E5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514415112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz A, Borst A, Haag J. Nonlinear integration of binocular optic flow by DNOVS2, a descending neuron of the fly. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3131–3140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5460-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz A, Haag J, Borst A. Local and global motion preferences in descending neurons of the fly. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2009;195:1107–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00359-009-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Laurent G. Role of GABAergic inhibition in shaping odor-evoked spatiotemporal patterns in the Drosophila antennal lobe. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9069–9079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2070-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie DR, Frost BJ. Binocular neurons in the nucleus of the basal optic root (nBOR) of the pigeon are selective for either translational or rotational visual flow. Vis Neurosci. 1990;5:489–495. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie DR, Frost BJ. Responses of pigeon vestibulocerebellar neurons to optokinetic stimulation. II. The 3-dimensional reference frame of rotation neurons in the flocculus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2647–2659. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie DR, Bischof WF, Frost BJ. Common reference frame for neural coding of translational and rotational optic flow. Nature. 1998;392:278–282. doi: 10.1038/32648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie DR, Kripalani T, Frost BJ. Responses of pigeon vestibulocerebellar neurons to optokinetic stimulation. I. Functional organization of neurons discriminating between translational and rotational visual flow. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2632–2646. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanker JM. On the mechanism of speed and altitude control in Drosophila melanogaster. Physiol Entomol. 1988;13:351–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]