Abstract

Aging is characterized by rising susceptibility to development of multiple chronic diseases and, therefore, represents the major risk factor for multimorbidity. From a gerontological perspective, the progressive accumulation of multiple diseases, which significantly accelerates at older ages, is a milestone for progressive loss of resilience and age-related multisystem homeostatic dysregulation. Because it is most likely that the same mechanisms that drive aging also drive multiple age-related chronic diseases, addressing those mechanisms may reduce the development of multimorbidity. According to this vision, studying multimorbidity may help to understand the biology of aging and, at the same time, understanding the underpinnings of aging may help to develop strategies to prevent or delay the burden of multimorbidity. As a consequence, we believe that it is time to build connections and dialogue between the clinical experience of general practitioners and geriatricians and the scientists who study aging, so as to stimulate innovative research projects to improve the management and the treatment of older patients with multiple morbidities.

Keywords: Multimorbidity, multiple morbidities, aging, chronic disease

Multi-morbidity: Implications and Challenges for Medical Care and Research

The aging of the world’s population and its increasing longevity during recent decades induced profound changes in the world’s political and economic landscape and presented many challenges to health and social care systems. In response, medical science created new diagnostic and therapeutic tools that improved rates of long-term survival for patients affected by chronic morbidity and an increasing prevalence of multiple chronic conditions. Noteworthy for this discussion, multimorbidity, the co-occurrence of 2 or more chronic diseases in an individual patient, has become recognized as the most common chronic medical condition. That milestone marks the transition from the era of “single chronic disease medicine” to the era of “multimorbidity medicine.”1

For centuries, medical science evolved around the nosology and pathophysiology of single diseases and devoted little to no study to the coexistence of multiple chronic conditions in a single patient. Progressively, it has become clear that the paradigm of “1 patient–1 disease” no longer fits the medical necessities and needs of most patients, and that a more holistic, patient-centered view should be developed.2–4 Indeed, in recent years, the literature on multimorbidity has grown exponentially, providing clear evidence of flourishing attention from the scientific and medical world to this emerging issue. Despite this explosion of interest, there remains a dearth of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practices for treating multiple chronic conditions in patients. Worse, it is unlikely that such guidelines will be developed soon because individuals with multiple diseases are excluded from clinical trials.5–11

In the literature, “multimorbidity” is usually addressed from the point of view of general practitioners (GPs).12,13 The relevant impact of multimorbidity in primary care is undeniable; however, the emerging importance of multimorbidity in the aging field is even more striking. In writing this report, we reviewed the existing literature and want to provide fresh insights about multimorbidity from a gerontological perspective. We conclude that it is time to build bridges between the clinical experience of GPs and geriatricians and the research of scientists who study aging. Such connections and dialogue would stimulate innovative research and other projects to improve the care of older patients and others who experience multiple morbidities.

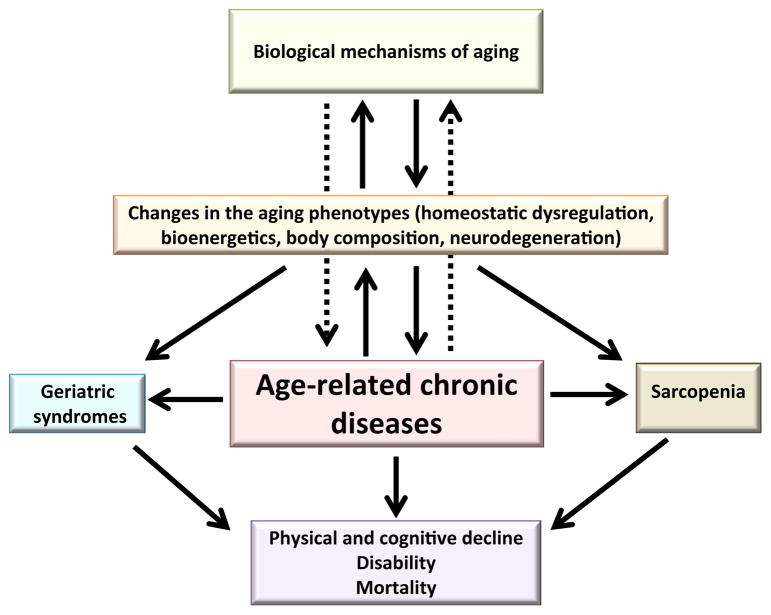

One complexity in understanding multimorbidity is that diseases can coexist in the same individual for several reasons, including random chance, common risk factors or mechanisms, and iatrogenic complexities.14 Indeed, aging is the strongest risk factor for many chronic diseases. Perhaps this is because aging brings with it the chronic dysregulation of multiple organ systems. When a threshold of impairment is reached, such breakdown in regulation among several organs and tissues becomes evident to clinicians (Figure 1). From a gerontological perspective, accumulation of diseases in an older adult is a milestone for progressive loss of resilience and homeostasis. Like the tip of an iceberg, this marker constitutes a red flag for the underlying onset of accelerated aging. Thus, measures of multimorbidity can provide effective tools in clinical and research settings to identify individuals who age faster than others. Likewise, this approach to research can improve our understanding of the mechanisms of aging and help to develop effective strategies for preventing and limiting the burdens of multimorbidity in older persons.

Fig. 1.

The age-related multisystem loss of reserve and function, rooted in the biological determinants of the aging process, is associated with increased susceptibility for chronic diseases, which becomes clinically evident as multimorbidity when a certain threshold of impairment has been a reached.

Definition of Multimorbidity

The Lack of a Standardized Operational Approach

“Comorbidity” and “multimorbidity” are often used as interchangeable terms. However, in recent years, comorbidity more often describes the combined effects of additional diseases in reference to an index disease (eg, comorbidity in cancer). Meanwhile, multimorbidity is more often meant to describe simultaneous occurrence of 2 or more diseases that may or may not share a causal link in an individual patient.15–17 Such distinctions certainly help; however, methodological problems affecting the measurement and operational definition of multimorbidity still persist, while no consensus about these parameters appears to be emerging.18 Many measurement tools have appeared in the literature. They vary from complex indexes of severity, complications, treatment, and prognosis to simple counts of diagnosed diseases. Nonetheless, no consensus exists for diagnostic criteria or the types and weightings of such diseases, which encompass a few to more than 150 different conditions. Lack of consensus and standardization makes it difficult to compare findings across studies. To overcome this confusing heterogeneity and fashion a uniform approach, Fortin and colleagues18 suggested that a good compromise is to include at least the 12 most prevalent chronic diseases that place the greatest burden in the population. Although this approach is agreeable, when assessing geriatric patients, we believe also that indices of multimorbidity should specify conditions known to be highly prevalent and strong risk factors for disability among older people. Moreover, geriatric syndromes, which most studies have omitted, should be considered in future investigations.19 Indeed, a gold standard definition for “geriatric multimorbidity” and its validation across different populations and clinical settings are high priorities for gerontological research and the design of new care systems for rapidly aging populations.

Epidemiology of Multimorbidity

The Growing Burden of Chronic Diseases

According to a recent report, nearly 80% of Medicare beneficiaries have at least 2 chronic conditions and more than 60% have at least 3 chronic conditions.20 Experts estimate that 26% of the US population will be living with multiple chronic conditions by 2030.21 Although multimorbidity is not limited to older adults, its prevalence increases substantially with age. In a cross-sectional study that included 1.7 million patients in Scotland, Barnett and colleagues22 found that 30.4% of the population aged 45 to 64 years, 64.9% of people aged 65 to 84 years, and 81.5% of people aged 85 years or older reported at least 2 chronic conditions. Data from the representative sample included in the Italian InCHIANTI study suggested that the rise of multimorbidity with age is not linear but rather that it significantly accelerates when the elderly achieve older ages.23

Risk Factors

Every published study describes the strong association of multimorbidity with age, and no study doubts that age is the main risk factor for prevalent and incident multimorbidity.22–42 Most evidence also acknowledges gender differences, notably a prevalence of multimorbidity higher among women than men.24,29,33,36,37,41,42 Furthermore, lower socioeconomic status and lower education are well-established risk factors for multimorbidity, an effect that is particularly evident for mental health disorders.22,24,29,33,34,37,41,42

Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity remain less explored and controversial. Studying Medicare beneficiaries, DuGoff and colleagues20 reported multimorbidity among white higher than among African American individuals. Meanwhile, a recent report about a geographically defined American population (Olmsted County, Minnesota) showed that multimorbidity was somewhat more prevalent among African American individuals and slightly less prevalent among Asian than white individuals.39 Partially echoing that finding, the Health and Retirement Study presented a longitudinal report on ethnic trajectories of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults during 11 years of follow-up data collection. Its findings revealed that Mexican American individuals had lower initial levels and slower accumulation of multimorbidity when compared with white individuals, whereas African American individuals, when compared with white individuals, presented an elevated level of multimorbidity along with a slower rate of increase throughout the period of observation.43

Traditional lifestyle factors have been most often investigated for their relationships to individual chronic diseases. However, several studies have reported that obesity is a risk factor for multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults.37,44–47 Yet evidence for the association of multimorbidity with patients’ levels of physical activity and exposures to cigarette smoking is inconsistent and controversial. Meanwhile, no association has been found between multimorbidity and alcohol consumption.37,41,47–49

Reducing the Complexity of Multimorbidity: Pairs, Clusters, Patterns, Networks, and Trajectories

In recent years, cross-sectional studies have focused on the identifications of patterns of associative multimorbidity, a term specifying pairings of diseases that develop in individuals at a higher rate than expected from pure chance.50 In 1998, Van den Akker and colleagues24 published a landmark article that tested the hypothesis that certain diseases tend to appear in clusters. Working in a large general practice, the investigators used data on the prevalence of diseases to calculate the expected prevalence of multimorbidity on the basis of pure chance. The authors found that more people than expected had no disease or had 4 or more diseases, whereas fewer people than expected had 1 or 2 diseases. These findings suggest that some individuals tend to develop a global susceptibility to multiple diseases, whereas others appear to be unusually resistant. In other words, associations of some specific diseases are not due to chance alone.

Since 1998, numerous studies have attempted to describe possible patterns of associative multimorbidity to generate helpful evidence for actual clinical practice and management.36,51–60 These studies have been largely heterogeneous for sample size, age, settings, indices of multimorbidity, and statistical methods (observed-to-expected ratio, cluster analyses, factor analyses, and multiple correspondence analyses). However, the absence of standardization in methods resulted in high variability among studies and inconsistent results that were difficult to compare.50,61 A recent study of older primary care populations from 2 different European countries identified 3 main disease patterns in the cardio-metabolic, psycho-geriatric, and mechanical domains. Similar findings emerged from a literature review.50,62

Despite their speculative value, it is not clear whether these findings can provide innovative and useful insights, beyond confirming that diseases with common pathophysiological pathways tend to occur in the same individuals. In the US Medicare study, Hidalgo and colleagues63 were the first to use the mathematics of network theory, a slightly more integrative approach, to study multimorbidity and its underlying mechanisms. These authors generated a visual map of disease associations, known as a Phenotypic Disease Network. It expresses the strength of association between diseases as the “distance” between them.63–65 Visual maps have the potential to simplify the identification of specific patterns and profiles of multimorbidity and to highlight potential predictors and consequences. Using the same approach, Schäfer and colleagues66 identified low-back pain as the medical condition in their data set with the highest number of associations. Their study also described multiple associations between disorders of the metabolic syndrome, of which hypertension was the central disease, and found prominent bridges between the metabolic syndrome and musculoskeletal disorders. However, despite the effort to grasp the complete picture of multimorbidity, the network visualization of the complex interactions among diseases remains far removed from translation into clinical practice guidelines. Perhaps a more useful yet still largely unexplored method requires estimating longitudinal trajectories of accelerated and impending multimorbidity. This method would aim to identify critical points in time when the age-related rise in multimorbidity becomes steeper. This method would allow the testing of hypotheses about characteristic events that occur before and at those critical times. Strauss and colleagues67 used data from a large UK general practice population aged 50 years or older and followed the study subjects for 3 years. Using latent class-growth analyses, their work identified 5 distinct trajectories of multimorbidity: a non–chronic morbidity cluster (40%), including those who had no chronic morbidity; an onset chronic morbidity cluster (10%), including patients who developed a first chronic morbidity during the study; a newly developing multimorbidity cluster (37%), including those who developed multimorbidity over time; an evolving multimorbidity cluster (12%), including patients with increasing counts of diseases over time; and a multichronic, multimorbidity cluster (1%) identifying patients who enter the multichronic cluster with multimorbidity. This important preliminary work should facilitate the identification of risk factors that indicate probable expansion of multimorbidity in individual patients. In the end, innovative and useful insights into the pathogenesis of multimorbidity will depend on longitudinal analyses of diseases. These studies would explore temporal and causal relationships among the accumulating multiple chronic conditions of individual patients. Such studies may be useful for clinical management of patients with multiple chronic diseases. They might stimulate the development of preventive strategies that also conceptualize prevention as delayed onset of multimorbidity and its components.

Multimorbidity in Gerontology’s Perspective

Biological Mechanisms Linking Aging to Chronic Diseases

Acknowledging that aging is the major risk factor for most chronic diseases also inspires the idea that slowing the process of aging represents a fruitful approach to delaying or preventing chronic conditions affecting the elderly. During recent decades, the integrative nature of human physiology has become much more clearly apparent. Pathologies once thought to be distinct from each other are now understood to be connected. Consequently, traditional research on aging that investigates single-disease conditions in isolation is no longer sufficient. Fortunately, the need for a more integrated approach that examines aging mechanisms across many states of disease is emerging.68 Moreover, basic research that studies the biological underpinnings of aging in animal models demonstrates that a significant delay in the appearance and progression of multiple morbidities and age-related functional decline produces an extension of life span. These findings confirm that slowing the aging processes leads to an increase in health span, the portion of life an individual spends in good health. Based on these concepts, a new interdisciplinary field of research for understanding mechanistic links between aging and age-related diseases, named “Geroscience,” has recently received considerable attention. Geroscience studies biological processes recognized to be common denominators of aging in different organs and organisms (Figure 1). The goal of Geroscience is to identify and develop therapies and preventive strategies for age-related diseases.69

In particular, the time-dependent accumulation of cellular damage is widely recognized as the general cause of aging. Characteristically, such damage causes a progressive loss of physiological integrity, which leads to impaired functions and increases vulnerability to death. Several interconnected cellular and molecular mechanisms have been proposed as common determinants of damage that cause aging and its resulting loss of homeostasis across different tissues and organs. These determinants include genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, protein-homeostasis loss, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem-cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication.70 Understanding these interacting biological processes and their causal contributions to age-related, multisystem failure may help scientists and clinicians to develop strategies and interventions aimed at decreasing the speed of aging and expanding human life span. In turn, such understanding will open clinical pathways to prevent or delay the onset of age-related chronic diseases and reduce the burdens of multimorbidity and disability in older adults.

Multimorbidity and Multisystem Effects of Aging

Our research group at the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging performed a series of studies on multimorbidity, using data from older adults enrolled in the InCHIANTI Study and the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Overall, these studies were aimed at elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms of multimorbidity and developing criteria to identify individuals at higher risk for multiple chronic conditions. Assuming that multimorbidity can be interpreted as a proxy measure of multisystem failures, we investigated the relationship between the accumulation of multimorbidity and accelerated development of typical aging phenotypes, including body composition, energetics, inflammation, and neurodegeneration (Figure 2).71 Testing both cross-sectional and longitudinal associations, while adjusting for relevant confounders, we found that, independent of chronological age, longitudinal changes in some of the most important aging phenotypes are highly correlated with expansion in multimorbidity. In particular, both higher baseline levels and steeper increases over time of interleukin (IL)-6, a robust biomarker of the proinflammatory state often observed in older individuals, predicted accelerated longitudinal accumulation of chronic diseases.22 Because previous studies have found that the level of IL-6 is an independent predictor of multiple adverse outcomes in older persons, including disability and mortality, these data suggest that high IL-6 and greater increase in IL-6 over time are markers of biological mechanisms that underlie multimorbidity evolving with aging and may be measured to target older individuals for interventions to reduce the burden of multimorbidity. Following similar reasoning, we investigated how energy metabolism may affect the development of multimorbidity. Resting metabolic rate, which is the minimal amount of energy required for basic survival, is a biomarker of homeostatic effort, whereas insufficient levels of resting metabolic rate are associated with heightened risk of mortality. We found that, consistent with our assumption, resting metabolic rate higher than expected for a certain age, sex, and body composition predicted future greater development of chronic diseases.72 Finally, we explored the relationship between rising multimorbidity and changes in body composition in older adults.73 In agreement with other studies, we found that obese individuals were associated with a greater burden of diseases compared with normal-weight and overweight individuals. However, in older adults who were obese at baseline, loss of weight over time, rather than weight gain, was longitudinally associated with the most dramatic rise in the number of chronic conditions. Interestingly, weight loss, which is also a diagnostic criterion for the frailty syndrome, represents an early clue to ongoing deterioration of health and a strong sign of accelerated accumulation of multimorbidity in obese older adults.

Fig. 2.

The accumulation of chronic diseases with increasing age, which is strongly associated with changes in all aging phenotypes and high risk for physical and cognitive decline, disability and mortality, can be conceptualized as a fulcrum of the aging process and a proxy measure of the speed of aging. Relationships and associations already established and recognized are represented by solid arrows, whereas those that have been hypothesized but not fully explored or understood are represented by dotted arrows.

Clinical Challenges of Multimorbidity

The Example of Dementia

Dementia is presented here as an example of an index disease that embodies all the complex challenges of multimorbidity. First, patients with dementia have a higher number of comorbidities than any other long-term disorder.74 In particular, they present on average 4 additional chronic medical conditions, including the 2 most frequent: hypertension and diabetes.4 Second, dementia itself often may be considered an expression of multimorbidity (involving both vascular and degenerative components). Indeed, study of dementia’s comorbidities will enrich understanding of the functional consequences of accelerated aging. In longitudinal studies, the presence of multimorbidity in patients with dementia has been associated with accelerated functional decline.75 Certain medical comorbidities also can exacerbate cognitive and mental deterioration in patients with dementia.76 For example, type 2 diabetes is well-known to be associated with the higher risk and faster progression of dementia in older people, probably as the result of common pathogenic mechanisms and denominators such as inflammation.77 Using data from a large sample of cognitively healthy, community-dwelling older adults enrolled in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, Song and collaborators78 found that the age-associated decline in health status, operationalized as an index variable, was significantly associated over 5-year and 10-year follow-up with the incidence of Alzheimer dementia and dementia of all types, even after adjusting for chronological age and traditional risk factors such as stroke and diabetes. However, other evidence of the effect of overall multimorbidity on cognitive decline produced contradictory findings.75 Future investigations should confirm whether overall multimorbidity, beyond specific medical conditions, can directly affect cognitive deterioration in older adults and also clarify its underlying mechanisms. Additionally, whether accelerated cognitive decline can be attributed to drug treatments for a comorbid disease is unknown. Addressing this question may have important clinical implications.

Multimorbidity and Health-related Outcomes

An inverse relationship between increasing multimorbidity and health-related quality of life is well-documented in the literature, and the evidence shows that physical health is affected more than mental health by the presence of multiple diseases.79 In fact, patients with multimorbidity are highly likely to be functionally impaired or disabled, with increasing risk of immobility and functional dependency according to increasing number of chronic diseases.80–82 Interestingly, some studies reported that even one newly diagnosed chronic condition is associated with nearly twice the likelihood of functional dependency onset during 12, 24, and 36 months of follow-up.83 Neuropsychiatric disorders, in particular, present the strongest association with poor quality of life and functional impairment.84 In addition, a few studies found a negative cross-sectional association between multimorbidity and grip strength.85–87 Finally, much evidence has shown that multimorbidity predicts mortality, with life expectancy substantially declining as the number of chronic conditions in individuals increases to 3 or more diseases.20,88,89 However, some studies pointed out that the association with mortality may be mediated by disability.89 Furthermore, patients affected by multiple chronic diseases are more likely to receive multiple drugs, face difficulties with therapeutic compliance and greater vulnerability to adverse events, suffer more psychological distress and depression, be admitted more often to a hospital, and face longer hospital stays.90–92 Not surprisingly, higher multimorbidity is associated with higher health care utilization and higher health care expenditure.34,93,94

The Paradigm of Multimorbidity Should Drive the Future of Health Care

Although patients with multiple chronic conditions are becoming more and more the “norm” in general and geriatric medicine, most studies in this field are theoretical and speculative. Not surprisingly, research on effective management strategies and interventions to improve outcomes in older patients affected by complex multimorbidity also remains limited.95 In an Irish survey involving a large number of care providers, including GPs and pharmacists, most participants reported challenges in managing health problems in complex patients. Their issues related to lack of time, interprofessional communication difficulties, and fragmentation of care.96 Proposed solutions to such difficulties included more structured care, longer consultations, specialist support, and training based on evidence-based guidelines.

Unfortunately, most evidence-based clinical guidelines focus on the management of single diseases.5–11 Creating guidelines that specifically target patients with multiple chronic diseases is a complex undertaking because such patients are often excluded from clinical trials and are not specifically identified in postmarketing drug surveys. This is a problem because therapeutic and adverse effects are likely different in patients with multimorbidity when compared with individuals with a single disorder. Moreover, management of these patients does not necessarily correspond to the optimal treatment of each of their individual chronic diseases.97–99 In particular, undesirable combinations of drugs elevate the risk of adverse drug reactions, and the risks grow as the number of medications increases for an individual patient.100–102 The problem of polypharmacy also gives rise to complex interactions among multiple drugs and between a patient’s drugs and his or her multiple diseases.

Older adults with multimorbidity are usually prescribed multiple medications for their individual conditions. Although benefiting one condition, some medications may adversely affect other coexisting conditions. Specifically, the term “therapeutic competition” refers to one type of disease-drug interaction in which a treatment recommended for one condition may adversely compete with another condition. In a nationally representative sample of older US adults, more than 20% took at least one medication that could adversely affect another of their chronic conditions.103 Clinicians need to prioritize which medications are most likely to benefit and least likely to harm an individual patient. However, knowledge in this area of medicine is limited.104

The evidence is emerging to support a structured approach to safe and effective cessation of medication, known as “de-prescribing,” with the goals of minimizing harm and improving outcomes from polypharmacy.105–108 Nonetheless, more information is needed to translate general clinical practice guidelines into specific recommendations for the care of multimorbid patients and to develop specific prognostic tools to optimize the management of complex patients in various care settings, regardless of whether the patient receives primary care from a physician or intensive treatment in a hospital.

As argued earlier, the challenge for appropriate management of complex, multimorbid patients is to provide “the right care for the right person at the right time.”109 A novel integrated-care model implemented in a facility located at Capital Health, Nova Scotia, Canada,110 exemplifies an excellent attempt to meet such challenges. The model proposes that complex geriatric patients affected by chronic diseases be managed according to a health care plan designed and delivered by a multidisciplinary team. The model features the integration of community resources, self-management support, delivery-system redesign, decision-making and organizational support, clinical information systems, and education modules to improve skill and coping strategies. The goal of this type of care model, which transcends traditional disease-specific approaches, is to satisfy the multifaceted needs of patients coping with multimorbidity and its constellations of symptoms and necessities. “Integration” and “multidisciplinary approach” should be rallying cries for reformation of health care from its current disease-centric paradigm and drive its conversion to clinical practices centered on the complex illnesses of individual patients. Research also must produce new information about methods of managing patients with multimorbidity. Indeed, this type of information is essential for the training of future leaders among health care providers “specialized” in treating complex geriatric patients.

New Directions for the Future

Despite the exponential growth of literature on geriatric multimorbidity and its research tasks, a number of critical questions remain unsolved. Perhaps the essential first step is to create a consistent definition and standardized metric of multimorbidity, which can then be validated among different settings and populations. Such a tool would facilitate studies of biological mechanisms for the accumulation of multimorbidity in some individuals at levels greater than the occurrence of morbidity expected from the prevalence of individual diseases in the population. The strong association of rising multimorbidity with changes in multiple aging phenotypes, which we described previously, suggests that multimorbidity is the result of age-related impairments to multiple systems and organs. When a certain threshold is reached, these impairments become clinically manifested as multiple chronic diseases. In other words, the rate of expansion in multimorbidity may be interpreted as a proxy for the speed of aging.

According to this hypothesis, we expect that the accumulation of conditions may occur stochastically rather than occur in precisely ordered clusters of disease and programmed causal interactions. This hypothesis explains why different studies have generally reported inconsistent results.

Moreover, the interaction of frailty and multimorbidity has not been adequately conceptualized or understood. In geriatric medicine, the 2 conditions have been usually considered 2 distinct clinical entities that are causally related.111 The distinction relies on the epidemiological observation that many but not all individuals with multimorbidity meet criteria for frailty syndrome and vice versa. This is particularly true when frailty is operationalized using the phenotypic definition, based on the 5 components: low grip strength, slowness by slowed walking speed, low level of physical activity, low energy or self-reported exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss.112 In contrast, the Frailty Index developed by Rockwood and colleagues, which operationalized frailty as accumulation of deficits, including a combination of symptoms, conditions, physical and cognitive impairments, psychosocial risk factors, and common geriatric syndromes, incorporates the presence and the number of diseases in the definition of frailty itself.113 According to Rockwood’s approach, in fact, the proportion of potential deficits present in a person indicates the likelihood that person is frail,113 without any intention to distinguish frailty from disability or multimorbidity. Indeed, if we think of frailty as the aggregation of subclinical losses of reserve across multiple physiologic systems and multimorbidity as the aggregation of multiple clinically manifested system failures, then both concepts may be conceptualized as diverse expressions of the same phenomenon, namely, age-related loss of resilience and inability to cope with external stressors. In this vision, we can interpret age-related accumulation of chronic diseases as the fulcrum of the aging spiral, driving a vicious downward risk of geriatric syndromes, physical and cognitive decline, disability, and mortality (Figure 2). Consequently, identifying those individuals who show accelerated rises in numbers of chronic conditions over time becomes essential to strategies that slow the progression of aging and the burdens of multimorbidity. Therefore, in scope, metrics of multimorbidity overlap some frailty indexes. For example, the “Frail” Scale, a small and easy-to-use screening tool to identify persons at risk for frailty, which partially combines aspects of the physical phenotypes and the Frailty Index, includes a metric of multimorbidity (number of illnesses) among its criteria, together with fatigue, resistance, ambulation, and loss of weight.114 However, we believe that, despite an inevitable overlap between the 2 concepts and their scopes, it is important to keep a distinction between frailty and multimorbidity. In particular, whereas metrics of frailty should be mainly aimed at identifying, above and beyond the chronological age of the person, the presence of a preclinical condition of high vulnerability to stressors with consequent increased risk to develop adverse outcomes, including morbidity and disability, metrics of multimorbidity provide a measure of the clinical expression of such vulnerability.

Because it is most likely that the same mechanisms that drive aging also drive multiple age-related chronic diseases, addressing those mechanisms may reduce the development of multimorbidity and realize a substantial gain in health status. From this perspective, studying multimorbidity can help us to understand aging. At the same time, understanding these basic dynamics affecting the health of aging people can help us to create strategies to prevent or delay the burden of multimorbidity (Table 1). To achieve this goal, more investigations of large populations, gathering data during long-term follow-up, are needed to identify trajectories of accelerated rise in multimorbidity and compare them to overall trajectories of morbidity in the general population. These trajectories could be used further in translational studies that explore how biological mechanisms of aging and cellular diseases (ie, epigenetic and “omics”) contribute to multimorbidity. Such research promises to identify novel biomarkers and pathways to target for early diagnosis and intervention. Furthermore, the relationship of multimorbidity to health outcomes, with particular attention to physical and cognitive decline, should be better explored so that specific prognostic tools can be developed. For example, knowledge about the rising effects of multimorbidity on longitudinal decline in muscle strength, muscle quality, mobility, cognition, and other typical phenotypes of aging would be very valuable in the clinical setting. In addition, new studies investigating potential interventions or management strategies to improve the care of complex, multimorbid patients are critical to progress in patient-centered health care. In particular, clinical trials that target patients with multiple chronic conditions and test the efficacy of treatments with multiple drugs are needed for clinical practice guidelines. Relying on them, GPs and specialists will improve their management and care of complex patients. As the world’s population continues to age, the transition from a disease-centered to a patient-centered system of care has become a necessity that no longer can be delayed. The multidimensional skills and expertise that geriatricians have already been using in clinical practice should drive this transformation.

Table 1.

Summary of the Key Concepts

|

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307:2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1–E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin CM, Félix-Bortolotti M. Person-centred health care: A critical assessment of current and emerging research approaches. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20:1056–1064. doi: 10.1111/jep.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee S. Multimorbidity—older adults need health care that can count past one. Lancet. 2015;385:587–589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortin M, Dionne J, Pinho G, et al. Randomized clinical trials: Do they have external validity for patients with multiple comorbidities? Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:104–108. doi: 10.1370/afm.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell-Scherer D. Multimorbidity: A challenge for evidence-based medicine. Evid Based Med. 2010;15:165–166. doi: 10.1136/ebm1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd CM, Vollenweider D, Puhan MA. Informing evidence-based decision-making for patients with comorbidity: Availability of necessary information in clinical trials for chronic diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roland M, Paddison C. Better management of patients with multimorbidity. BMJ. 2013;346:f2510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd CM, Kent DM. Evidence-based medicine and the hard problem of multimorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:552–553. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2658-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Giovannetti E, et al. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med Care. 2014;52:S118–S125. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a977da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muth C, van den Akker M, Blom JW, et al. The Ariadne principles: How to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014;12:223. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neale MC, Kendler KS. Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:935–953. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Manceau B, et al. The European General Practice Research Network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA. Comorbidity or multimorbidity: What’s in a name. A review of literature. Eur J Gen Pract. 1996;2:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yancik R, Ershler W, Satariano W, et al. Report of the national institute on aging task force on comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:275–280. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd CM, Ritchie CS, Tipton EF, et al. From bedside to bench: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Comorbidity and Multiple Morbidity in Older Adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:181–188. doi: 10.1007/bf03324775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: Toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:142–151. doi: 10.1370/afm.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DuGoff EH, Canudas-Romo V, Buttorff C, et al. Multiple chronic conditions and life expectancy: A life table analysis. Med Care. 2014;52:688–694. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson G. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabbri E, An Y, Zoli M, et al. Aging and the burden of multimorbidity: Associations with inflammatory and anabolic hormonal biomarkers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:63–70. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: Prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:223–228. doi: 10.1370/afm.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker AE. Multiple chronic diseases and quality of life: Patterns emerging from a large national sample, Australia. Chronic Illn. 2007;3:202–218. doi: 10.1177/1742395307081504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schram MT, Frijters D, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Setting and registry characteristics affect the prevalence and nature of multimorbidity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marengoni A, Winblad B, Karp A, Fratiglioni L. Prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly population in Sweden. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1198–1200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: Prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14:28–32. doi: 10.1080/13814780802436093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189:72–77. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider KM, O’Donnel BE, Dean D. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ Medicare population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, et al. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e12–e21. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glynn LG, Valderas JM, Healy P, et al. The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Fam Pract. 2011;28:516–523. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schafer I, Hansen H, Schon G, et al. The influence of age, gender and socioeconomic status on multimorbidity patterns in primary care. First results from the Multicare Cohort Study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Oostrom SH, Picavet HS, van Gelder BM, et al. Multimorbidity and comorbidity in the Dutch population—data from general practices. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagel G, Peter R, Braig S, et al. The impact of education on risk factors and the occurrence of multimorbidity in the EPIC Heidelberg cohort. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:384. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lochner KA, Cox CS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries, United States, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:e61. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocca WA, Boyd CM, Grossardt BR, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in a geographically defined American population: Patterns by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1336–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melis R, Marengoni A, Angleman S, Fratiglioni L. Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity in the elderly: A population-based longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: A systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quiñones AR, Liang J, Bennett JM, Xu X, Ye W. How does the trajectory of multimorbidity vary across Black, White, and Mexican Americans in middle and old age? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:739–749. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cornell JE, Pugh JA, Williams JW, et al. Multimorbidity clusters: Clustering binary data from a large administrative medical database. Applied Multivariate Research. 2007;12:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agborsangaya CB, Ngwakongnwi E, Lahtinen M, et al. Multimorbidity prevalence in the general population: The role of obesity in chronic disease clustering. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Impact of body mass index on prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: Cohort study. Fam Pract. 2014;31:38–43. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fortin M, Haggerty J, Almirall J, et al. Lifestyle factors and multimorbidity: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:686. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudon C, Soubhi H, Fortin M. Relationship between multimorbidity and physical activity: Secondary analysis from the Quebec health survey. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:304. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cimarras-Otal C, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Poblador-Plou B, et al. Association between physical activity, multimorbidity, self-rated health and functional limitation in the Spanish population. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prados-Torres A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Hancco-Saavedra J, et al. Multimorbidity patterns: A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, Wang HX, et al. Patterns of chronic multimorbidity in the elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marengoni A, Bonometti F, Nobili A, et al. In-hospital death and adverse clinical events in elderly patients according to disease clustering: The REPOSI study. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13:469–477. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schafer I, von Leitner EC, Schon G, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: A new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newcomer SR, Steiner JF, Bayliss EA. Identifying subgroups of complex patients with cluster analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:e324–e332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van den Bussche H, Koller D, Kolonko T, et al. Which chronic diseases and disease combinations are specific to multimorbidity in the elderly? Results of a claims data based cross-sectional study in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong A, Boshuizen HC, Schellevis FG, et al. Longitudinal administrative data can be used to examine multimorbidity, provided false discoveries are controlled for. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Calderon-Larranaga A, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in primary care: Interactions among chronic diseases using factor analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirchberger I, Meisinger C, Heier M, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in the aged population. Results from the KORA-age study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freund T, Kunz CU, Ose D, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in primary care patients at high risk of future hospitalization. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15:119–124. doi: 10.1089/pop.2011.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garcia-Olmos L, Salvador CH, Alberquilla A, et al. Comorbidity patterns in patients with chronic diseases in general practice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinnige J, Braspenning J, Schellevis F, et al. The prevalence of disease clusters in older adults with multiple chronic diseases—a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poblador-Plou B, van den Akker M, Vos R, et al. Similar multimorbidity patterns in primary care patients from two European regions: Results of a factor analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hidalgo CA, Blumm N, Barabási AL, Christakis NA. A dynamic network approach for the study of human phenotypes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: A network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Divo MJ, Martinez CH, Mannino DM. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1055–1068. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schäfer I, Kaduszkiewicz H, Wagner HO, et al. Reducing complexity: A visualisation of multimorbidity by combining disease clusters and triads. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strauss VY, Jones PW, Kadam UT, Jordan KP. Distinct trajectories of multimorbidity in primary care were identified using latent class growth analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, et al. Geroscience: Linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burch JB, Augustine AD, Frieden LA, et al. Advances in geroscience: Impact on healthspan and chronic disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:S1–S3. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferrucci L, Studenski S. Clinical problems of aging. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fabbri E, An Y, Schrack JA, et al. Energy metabolism and the burden of multimorbidity in older adults: Results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging [published online ahead of print November 18, 2014] J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fabbri E, Tanaka T, An Y, et al. Loss of weight in obese older adults: a biomarker of impending expansion of multi-morbidity? J Am Geriatr Soc. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13608. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM, et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: Are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Melis RJ, Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, et al. The influence of multimorbidity on clinical progression of dementia in a population-based cohort. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leoutsakos JM, Han D, Mielke MM, et al. Effects of general medical health on Alzheimer’s progression: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1561–1570. doi: 10.1017/S104161021200049X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biessels GJ, Strachan MW, Visseren FL, et al. Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: Towards targeted interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:246–255. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Nontraditional risk factors combine to predict Alzheimer disease and dementia. Neurology. 2011;77:227–234. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225c6bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Relationship between multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-8661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guralnik JM, LaCroix AZ, Abbott RD, et al. Maintaining mobility in late life. I. Demographic characteristics and chronic conditions. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:845–857. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, Stalman WAB. Comorbidity of somatic chronic diseases and decline in physical functioning: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marengoni A, von Strauss E, Rizzuto D, et al. The impact of chronic multimorbidity and disability on functional decline and survival in elderly persons. A community-based, longitudinal study. J Intern Med. 2009;265:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wolff JL, Boult C, Boyd C, Anderson G. Newly reported chronic conditions and onset of functional dependency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:851–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marventano S, Ayala A, Gonzalez N, et al. Spanish Research Group of Quality of Life and Ageing. Multimorbidity and functional status in community-dwelling older adults. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Goodpaster B, et al. Strength and muscle quality in a well-functioning cohort of older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:323–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Welmer AK, Kareholt I, Angleman S, et al. Can chronic multimorbidity explain the age-related differences in strength, speed, and balance in older adults? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:480–489. doi: 10.3275/8584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yorke AM, Curtis AB, Shoemaker M, Vangsnes E. Grip strength values stratified by age, gender, and chronic disease status in adults aged 50 years and older. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38:115–121. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Menotti A, Mulder I, Nissinen A, et al. Prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity in elderly male populations and their impact on 10-year all-cause mortality: The FINE study (Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Elderly) J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:680–686. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.St John PD, Tyas SL, Menec V, Tate R. Multimorbidity, disability, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:e272–e280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Calderón-Larrañaga A, Poblador-Plou B, González-Rubio F, et al. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, referrals, and adverse drug events: Are we doing things well? Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e821–e826. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X659295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Psychological distress and multimorbidity in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:417–422. doi: 10.1370/afm.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith DJ, Court H, McLean G, et al. Depression and multimorbidity: A cross-sectional study of 1,751,841 patients in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:1202–1208. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: Prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bähler C, Huber CA, Brüngger B, Reich O. Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: A claims data based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: Systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Smith SM, O’Kelly S, O’Dowd T. GPs’ and pharmacists’ experiences of managing multimorbidity: A Pandora’s box. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:285–294. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Uhlig K, Leff B, Kent D, et al. A framework for crafting clinical practice guidelines that are relevant to the care and management of people with multimorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:670–679. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2659-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blozik E, van den Bussche H, Gurtner F, et al. Epidemiological strategies for adapting clinical practice guidelines to the needs of multimorbid patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:352. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weiss CO, Varadhan R, Puhan MA, et al. Multimorbidity and evidence generation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:653–660. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2660-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Doos L, Roberts EO, Corp N, Kadam UT. Multi-drug therapy in chronic condition multimorbidity: A systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31:654–663. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Veehof LJ, Stewart RE, Meyboom-de Jong B, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Adverse drug reactions and polypharmacy in the elderly in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s002280050669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kadam UT. Potential health impacts of multiple drug prescribing for older people: A case-control study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:128–130. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X556263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lorgunpai SJ, Grammas M, Lee DS, et al. Potential therapeutic competition in community-living older adults in the US: Use of medications that may adversely affect a coexisting condition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Holmes HM, Min LC, Yee M, et al. Rationalizing prescribing for older patients with multimorbidity: Considering time to benefit. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:655–666. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: The view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: Towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:121–124. doi: 10.1136/eb-2012-100930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reeve E, Wiese MD. Benefits of deprescribing on patients’ adherence to medications. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:26–29. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9871-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: The EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:890–898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bayliss EA. Simplifying care for complex patients. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:3–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sampalli T, Fox RA, Dickson R, Fox J. Proposed model of integrated care to improve health outcomes for individuals with multimorbidities. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:757–764. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S35201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56A:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abellan van Kan G, Rolland YM, Morley JE, Vellas B. Frailty: Toward a clinical definition. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:71–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]