Abstract

The ability to assess oxygenation within living cells is much sought after to more deeply understand normal and pathological cell biology. Hypoxia Red manufactured by Enzo Life Sciences is advertised as a novel hypoxia detector dependent on nitroreducatase activity. We sought to use Hypoxia Red in primary neuronal cultures to test cell-to-cell metabolic variability in response to hypoxic stress. Neurons treated with 90 min of hypoxia were labeled with Hypoxia Red. We observed that, even under normoxic conditions neurons expressed fluorescence robustly. Analysis of the chemical reactions and biological underpinnings of this method revealed that the high uptake and reduction of the dye is due to active nitroreductases in normoxic cells that are independent of oxygen availability.

Keywords: Fluorescence, hypoxia, nitroreductase, oxygen, oxygen and glucose deprivation

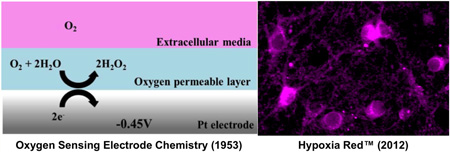

Graphical Abstract

As the role of cellular energetic status in controlling proliferation, survival and responses to internal or external stimuli becomes increasingly well understood, there is a pressing need to develop tools to rapidly and reliably assess cellular oxygenation. Traditionally, measuring aerobic and anaerobic respiration in dissociated cells and cell lines has relied on population recordings of oxygen consumption using electrodes, taking advantage of the linear relationship between dissolved oxygen concentration and the current collected at a platinum electrode held at a reducing potential.

Respiring cells utilize oxygen in growth medium, exhibiting a low current when measured with the platinum sensor. Inhibiting cellular respiration increases “free” oxygen, causing an increase in recorded electrical currents. More recently, a combination of oxygen consumption and tension measurement tools have been adapted to plate reader formats for higher throughput screening.1 This approach also relies on the measurement of extracellular oxygen in populations of live or permeablized cells, limiting their utility in understanding heterogeneous responses.2

Intracellular oxygen measurements can be obtained biochemically by radiolabeling, as well as with new oxygen dependent small molecules. Engineered fluorescent, biocompatible nanoparticles, have been designed where the oxygen-sensing probe is encapsulated in a hydrophobic shell for cell delivery and offer a promising means to assess individual cell responses.3 These nanoparticles have yet to be optimized, as current generation can leach probes and suffer from poor bioavailability in cell media.3 Detection of hypoxic environments that promote anaerobic metabolism requires probes to be stable and signals that are generated by irreversible reactions in response to decreasing oxygen concentration.

Oxygen-dependent signaling pathways are relatively easily probed with immunofluorescence or redox-dependent dyes. However, caution is warranted when choosing dyes that depend on members of oxygen-regulated signaling pathways, as cross talk with oxygen-independent pathways may interfere with assay results. For example, HIF1α protein expression is often utilized as a primary biomarker for hypoxia in tissue, and has been used to correlate hypoxia levels with tumor recurrence and progression. HIF1α stabilization is dependent on the activity of oxygen-sensitive prolyl-hydroxylase domain containing enzymes (PHDs). Yet, oxygen-independent HIF1α stabilization can be mediated by growth factors and environmental stimuli that promote reactive oxygen species, which in turn inhibit PHD activity.4–6

The first mass marketed probe “designed for functional detection of hypoxia… in live cells” is Hypoxia Red manufactured by Enzo Life Sciences. The Hypoxia Red signal is generated by reduction of nitro groups that release a stable, free fluorophore into the intracellular compartment of living cells.

Here, we describe the use of the Hypoxia Red dye in primary neurons and report that signal is present not only in cells following a 90 min hypoxic exposure but also is abundant in normoxic neurons in growth media. We discuss the role of media formulation in the synthesis of nitroreductase enzymes and how common media formulations may lead to false positive signal within normoxic cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Stabilized Nuclear HIF1α Is Robustly Expressed After Hypoxia

Primary rat cortical neurons were dissociated and grown in culture as previously described7 with minor modifications (see Methods). Mature neurons were exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) after 21–25 days in vitro. As neurons have heterogeneous vulnerability to low-level hypoxia, we sought to determine if the degree of oxygen deprivation correlated with survival. In order to demonstrate that 90 min of OGD is sufficient to induce hypoxia, we first compared hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF1α) protein induction in normoxic cultures and cultures exposed to mild OGD (15 min). HIF1α expression is a widely used measure of hypoxic stress, as its stability, localization, and transcriptional activity are affected by intracellular oxygen concentrations. Under normoxic conditions, the E3-ligase Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) and ubiquitin-protease pathway rapidly degrade HIF1α. During hypoxia HIF1α protein degradation is prevented, and HIF1α accumulates and translocates to the nucleus to transcribe target genes.6

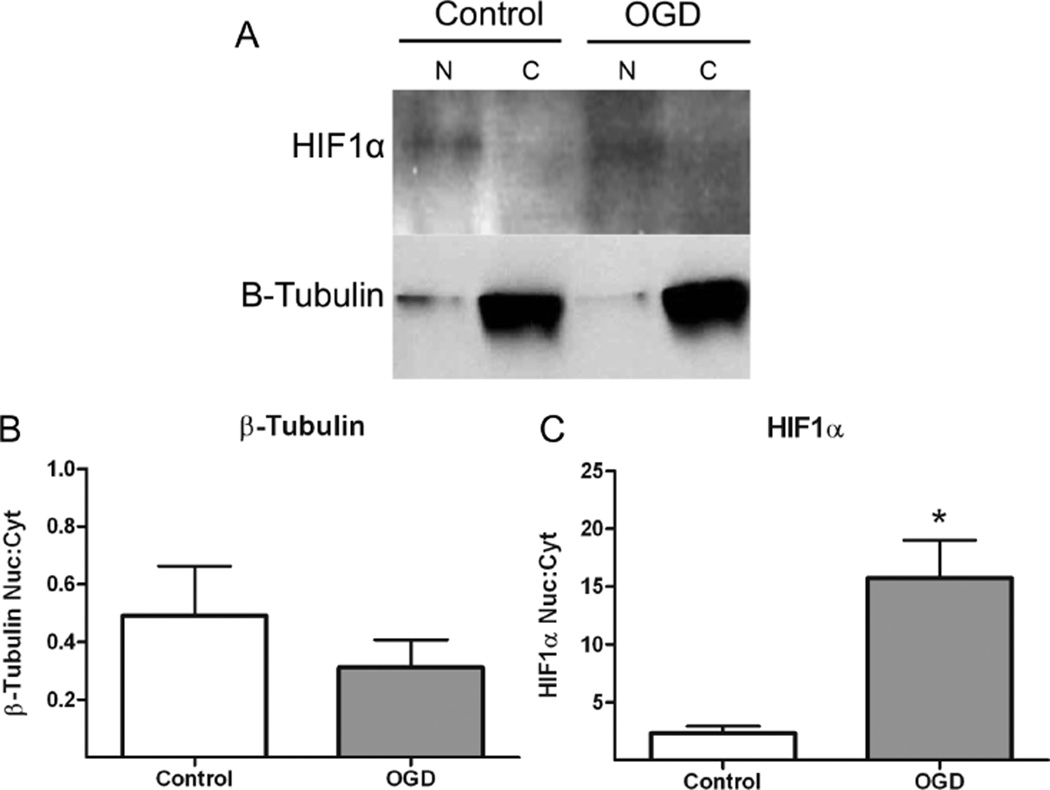

Cultures were harvested 6 h post-OGD and subcellular fractionation was performed to isolate stabilized, nuclear HIF1α. The resulting nuclear and cytosolic fractions were then prepared for Western blotting. We found that normoxic neurons express little to no cytoplasmic HIF1α and a basal level of nuclear HIF1α, while the protein is highly induced by 6 h post-OGD (Figure 1). Quantification of Western blots reveal a 5-fold increase in nuclear HIF1α after OGD compared to control (Figure 1C, p = 0.007), with no significant difference in β-tubulin expression (Figure 1B, p = 0.4). Based on these results, we conclude that a more severe OGD (90 min) would be sufficient to induce hypoxic stress in our cultures, and that our normoxic cultures exhibit no hypoxia-related stress signaling to induce HIF1α. Therefore, we predicted that, using this paradigm, Hypoxia Red will sufficiently and specifically label hypoxic neurons.

Figure 1.

Stabilized nuclear HIF1α is robustly expressed after hypoxia. (A) Primary neuronal cultures (DIV21–25) were exposed to normal growth media (control) or to 15 min OGD. Neurons were harvested 6 h after OGD and prepared for subcellular fractionation. Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared for Western blotting for HIF1α, a hypoxia-induced protein, and β-tubulin, a cytosolic loading control. Western blot analysis demonstrates that 15 min of OGD induces HIF1α protein expression and nuclear stabilization 6 h post-OGD. Normoxic control cultures exhibit little to no cytosolic or nuclear HIF1α expression. Quantification of band intensity reveals a 5-fold increase in nuclear HIF1α after OGD compared to control (C, n = 4, p = 0.007, *denotes significance). No significant difference in β-tubulin expression was observed (B, n = 4, p = 0.4).

Hypoxia Red Staining in Normoxic and Hypoxic Cells

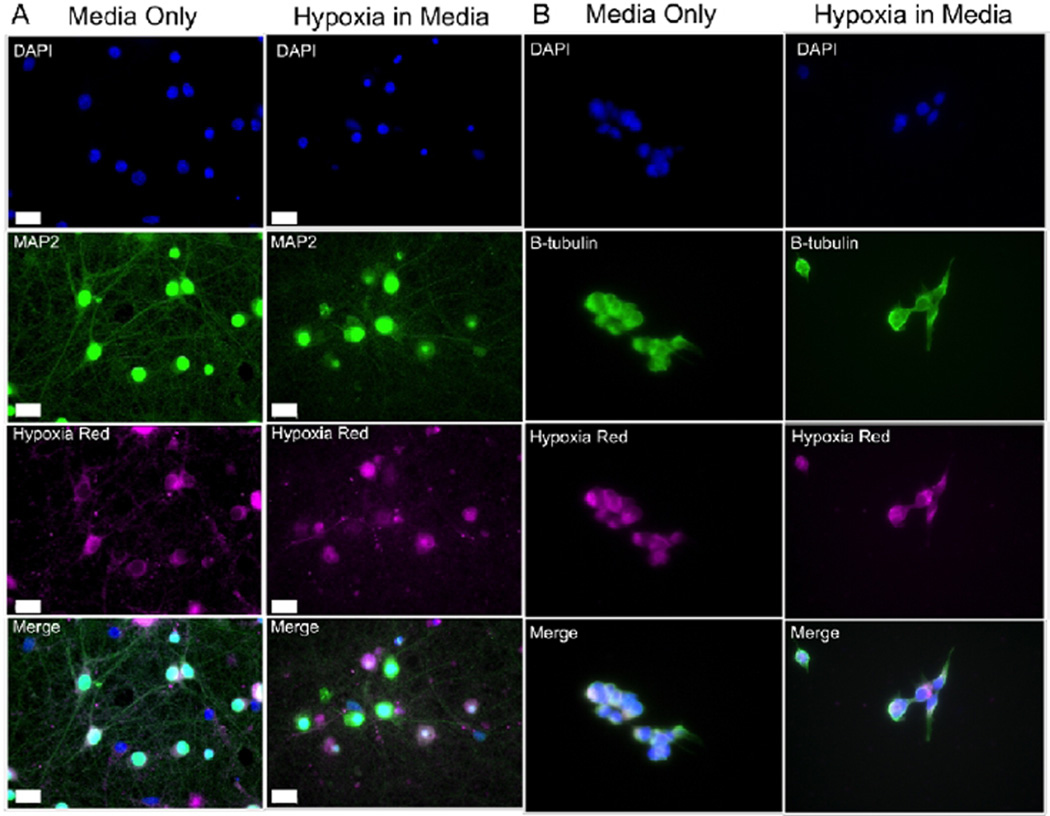

We have previously shown that a 90 min period of OGD is excitotoxic to neuronal cultures.7 We verified that cells were morphologically and biochemically compromised by DAPi and microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) staining and by assessing chaperone induction and cell survival. Neurons were loaded with dye (0.5 µM; Enzo Life Sciences) in deoxygenated growth media and then placed in a hypoxic chamber for 90 min at 37 °C as previously described.7 Neurons were then stained with MAP2 and DAPi using immunofluorescence techniques. Control cultures were loaded with dye in oxygen replete NB/NS21, washed after 90 min, and fixed for immunocytochemistry.

MAP2 is a neuron-specific protein enriched in dendrites, which diminishes as arbors retract following OGD (Figure 2; green) and nuclei stained with DAPi condense (Figure 2; blue). Cultures exposed to OGD also had increased expression of heat shock protein 70 within 6 h and >85% cell death by 24 h (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Hypoxia Red staining is robust in both normoxic and hypoxic cells. Primary neuronal cultures (A) or HEK293 cultures (B) loaded with Hypoxia Red (magenta) for 90 min in normal growth culture medium (Control) or during 90′ OGD. Post-treatment, cultures were washed twice with 1× PBS and immunocytochemistry was performed utilizing MAP2 (green) as a neuronal marker (A) or β-tubulin (B) and DAPi (blue) as a nuclear indicator. Cultures were imaged with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope at 40× magnification. While there is cell-to-cell variation in fluorescence intensity within each condition, Hypoxia Red fluoresces in the cell bodies of both normoxic control and hypoxic neurons and HEK293 cells. Colocalization and cell counts were analyzed with ImageJ, revealing no significant difference in the percent of cell population stained positive with Hypoxia Red (neurons: n = 3, p = 0.78; HEK293: n = 3, p = 0.85).

Although we have previously established that control primary neurons maintained in similar growth conditions stably consume oxygen and also show no signs of lactate dehydrogenase release or acidosis7,9 indicative of oxygen deprivation, we found that normoxic and hypoxic cultures both exhibited robust Hypoxia Red fluorescence, in live and fixed cells (Figure 2A; magenta). Quantification of the percent of neurons stained positive with Hypoxia Red revealed no significant difference between control cultures and cultures treated with 90 min OGD (Figure 2B, n = 3, p = 0.78).

In order to test whether false positive staining with Hypoxia Red dye is unique to primary neuronal cultures, we treated HEK293 cells with the dye, followed by 90 min of OGD in oxygen replete DMEM or in normoxic growth media. Hypoxic cultures and normoxic sister cultures were washed and fixed for immunocytochemistry with β-tubulin and DAPi. We found that, like primary neuronal cultures, both normoxic and hypoxic HEK293 cells stained positive with Hypoxia Red dye. Quantification of the percent of total cells stained positive with dye revealed no significant difference between control and OGD cultures (Figure 2C, n = 3, p = 0.85).

These data suggest that under conditions where NAD+ and NADH precursors are abundant, the reduction of the Hypoxia Red biosensor occurs unabated and is independent of intracellular oxygen concentrations. In support of our observations, detection of hypoxia in normoxic cells has been previously observed in nonfluorescent staining methods,10 and was attributed to high nitroreducase activity. The chemical reduction of the nitro group by pleotropic oxygen-dependent nitroreductases is, in most growth medias, not a function of oxygenation but rather NAD+/NADH levels. These levels may correlate with oxygenation in some conditions but can be regulated independently by the presence of high levels of NAD+ and NADH precursors including amino acids and pyruvate.

Hypoxia Red dye is advertised as a hypoxia detector yet the chemical reactivity and biological specificity reveal that they dye fluorescence may be solely dependent on nitroreductase activity, which can be influenced by factors unrelated to oxygen concentration, including cofactor concentration, local pH, and the classes of nitroreductases present.10–12 Moreover, the nitroreductases are a highly heterogeneous family of enzymes, which consist of both oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent enzymes, which vary among cell types between metabolic states. Standardization of Hypoxia Red dye signal would therefore be difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

Commercially available sensors to rapidly and reliably assess intracellular metabolic and redox status are highly coveted tools. Enzo’s Hypoxia Red dye is the first commercialized hypoxia probe advertised as part of a kit that detects oxygenation in live cells in real time. Like many commercial reagents sold as “kits”, specific details on the chemical structure of the probes is limited by vendors in an effort to dissuade investigators from purchasing chemically identical reagents from other retailers. As the chemistry and reactivity of Hypoxia Red remains to be further detailed, it is unknown whether the dye itself impacts cellular metabolic homeostasis. For example, SYTO 13, a commonly used fluorescent nuclear dye, has recently been found to decrease oxygen and glucose consumption, shifting cell metabolism toward anaerobic respiration upon exposure in macrophage and neuronal cell lines using the manufacturer-recommended dye concentrations.13

The subtlety of measuring metabolism and survival rather than mass reduction and oxidation of NADH is reminiscent of ongoing misinterpretations of other kit-based assays of “viability” and “indirect respiration” such as the MTT assay. This method is based on the cleavage of the yellow tetrazolium salt (MTT) by mitochondrial dehydrogenases generating purple formazan crystals, a process that requires NADH and NADPH. The crystals are dissolved in acidified isopropanol, and the purple solution is then measured spectrophotometrically. MTT assays, like the Hypoxia Red fluorescence, are a tool that is greatly limited in understanding cell physiology and must still be combined with biochemical assays of total ATP reserves, lactate generation or pyruvate stores to present a fuller picture of the cell’s metabolic profile. Given these limitations, it should be clear that none of these tools are capable of capturing metabolic events in individual living cells in a reliable manner at this juncture.

METHODS

User-friendly versions of all of the protocols and procedures can be found on our Web site at http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/root/vumc.php?site=mclaughlinlab&doc=17838.

Reagents

Cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Invitrogen. Mouse HIF1α primary antibody for Western blot was purchased from Novus Biologicals, and rabbit β-tubulin primary antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling. Rabbit MAP2 primary antibody for immunocytochemistry was purchased from Abcam, and antirabbit Cy2 secondary antibody was purchased from the Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory. Hypoxia Red dye was purchased as part of the CytoID Hypoxia/Oxidative Stress Detection Kit manufactured by Enzo Life Sciences (ENZ-51042). Other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise specified.

Primary Cell Culture

Primary rat forebrain neurons were obtained and cultured as previously described,7 with minor modifications indicated below. Briefly, embryonic day 18 Sprague–Dawley rat forebrains were dissected, dissociated, and adjusted to 750 000 cells/mL in growth media in 6-well plates containing 12 mm PLO-coated glass coverslips. Glial proliferation was halted using cytosine arabinoside (2–3 µM) after 2 days in vitro (DIV2). Neurons were maintained in Neurobasal-A medium supplemented with B27, NS21, and N2 until DIV17, when cultures were switched to Neurobasal medium supplemented with NS218 (NB/NS21). Experiments were conducted when cultures reached DIV21–25.

Oxygen and Glucose Deprivation (OGD)

In vitro OGD experiments were performed as previously described.7 Primary rat neurons plated on glass coverslips were transferred to 35 mm Petri dishes containing glucose-free balanced salt solution that had been bubbled with an anaerobic mix (95% nitrogen and 5% CO2) for 5 min immediately prior in order to remove dissolved oxygen. Dishes were then placed in a hypoxic chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) which was flushed with the anaerobic mix for 5 min, then sealed and placed at 37 °C for 10 min for a total exposure time of 15 min. OGD treatment was terminated immediately following the 15 min exposure by placing the glass coverslips into MEM media containing 10 mM Hepes, 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2× N2 supplement (MEM/Hepes/BSA/2×N2) under normoxic conditions for 6 h. All experiments were performed using cells derived from at least three independent original dissections.

Subcellular Fractionation

Neuronal cultures were exposed to 15 min OGD and cell lysates were prepared 6 h later. Subcellular fractionation via differential centrifugation was used to isolate nuclear and cytosolic compartments. Neurons were washed with ice-cold 1× PBS. Sucrose buffer (10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 250 mM sucrose, and protease inhibitor, pH 7.5) was added, and neurons were collected on ice via scraping and placed into a precooled Sorval tube that was centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in fresh sucrose buffer and incubated in ice for 30 min. Cells were then transferred to a homogenizer and dounced for roughly 40 strokes, followed by centrifugation at 50g for 10 min at 4 °C. Following this spin, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 800g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and the resultant nuclear pellet resuspended in TNEB lysis buffer. The remaining supernatant was centrifuged at 13 000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resultant mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in TNEB lysis buffer. The remaining supernatant from the previous spin was then centrifuged at 100 000g for 1 h at 4 °C. This cytosolic pellet is then resuspended in TNEB lysis buffer.

Western Blot Analysis

Equal protein concentrations as determined by BCA protein assay were separated using Criterion Tris-HCl gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride PVDF membranes (Amersham Biosciences) and blocked in methanol for 5 min. Following 10 min of drying, the membranes were incubated overnight with HIF1α in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-Tween (0.1%), washed three times with TBS-Tween, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. Following three washes in TBS-Tween, the protein bands were visualized using Western Lightning chemiluminsecence reagent plus enhanced luminol reagents (PerkinElmer Life Science).

Western Blot Quantification

ImageJ software (NIH) was used to quantify the pixel intensity of each lane for HIF1α and β-Tubulin Western blots. The data represents the mean from four independent experiments ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t test with p < 0.05.

Hypoxia Detection and Immunocytochemistry

Neurons were loaded with the Hypoxia Red dye (0.5 µM; Enzo Life Sciences) for 90 min in NB/NS21 at 37 °C. To achieve hypoxia, neurons were exposed to deoxygenated NB/NS21 plus dye in a hypoxic chamber for 90 min at 37 °C. After treatment, cultures were washed twice with 1× PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabalized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were washed with 1× PBS for a total of 15 min cells were blocked with 8% BSA in PBS for 25 min, and then immediately incubated in 1% BSA in PBS containing MAP2 primary antibody (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed in PBS for a total of 30 min followed by 1 h incubation in anti-rabbit Cy2 secondary antibody (1:500) in 1% BSA. Cells were washed in PBS for a total of 25 min, followed by incubation with 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 min. Cells were washed again for a total of 15 min in PBS and mounted on slides with Prolong Gold antifade reagent. Fluorescence was visualized with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope at 40×.

Colocalization and Cell Counting

ImageJ software (NIH) was used to identify the colocalization of Hypoxia Red and MAP2 fluorescence and perform cell counting. The data represents the mean from three independent experiments ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t test with p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (1UH2TR000491-01 and ES013125), the American Heart Association (14PRE20350007), and the Suzanne and Walter Scott Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

B.N.L.M. and S.K. acquired and analyzed data, and assembled Figures 1 and 2. J.R.M. assembled the Table of Contents graphic. D.E.C. and B.M. revised the article and were involved in interpretation of data. All authors contributed to experiment concept and design, and contributed to the written manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grodzki AC, Giulivi C, Lein PJ. Oxygen tension modulates differentiation and primary macrophage functions in the human monocytic THP-1 cell line. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Wisidagama DR, Setoguchi K, Hong JS, Van Horn CM, et al. Measuring energy metabolism in cultured cells, including human pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:1068–1085. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XD, Wolfbeis OS. Optical methods for sensing and imaging oxygen: materials, spectroscopies and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:3666–3761. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00039k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brune B, Zhou J, von Knethen A. Nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Kidney Int. 2003;63:S22–S24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s84.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan Y, Hilliard G, Ferguson T, Millhorn DE. Cobalt inhibits the interaction between hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha and von Hippel-Lindau protein by direct binding to hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15911–15916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agani F, Jiang BH. Oxygen-independent regulation of HIF-1: novel involvement of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:245–251. doi: 10.2174/1568009611313030003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeiger SL, McKenzie JR, Stankowski JN, Martin JA, Cliffel DE, McLaughlin B. Neuron specific metabolic adaptations following multi-day exposures to oxygen glucose deprivation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2010;1802:1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Stevens B, Chang J, Milbrandt J, Barres BA, Hell JW. NS21: re-defined and modified supplement B27 for neuronal cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;171:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenzie JR, Palubinsky AM, Brown JE, McLaughlin B, Cliffel DE. Metabolic multianalyte microphysiometry reveals extracellular acidosis is an essential mediator of neuronal preconditioning. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012;3:510–518. doi: 10.1021/cn300003r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb LM, Nolan J, O’Neill P. Microscopic distribution of misonidazole in mouse tissues. Br. J. Cancer. 1989;59:12–16. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin B, Pal S, Tran MP, Parsons AA, Barone FC, Erhardt JA, et al. p38 activation is required upstream of potassium current enhancement and caspase cleavage in thiol oxidant-induced neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:3303–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03303.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch CJ. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and 2-nitroimidazole EF5. Methods Enzymol. 2002;352:3–31. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)52003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinawi TF, Kimmel DW, Cliffel DE. Multianalyte microphysiometry reveals changes in cellular bioenergetics upon exposure to fluorescent dyes. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:11677–11680. doi: 10.1021/ac402764x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]