Abstract

The patient in this case study presented with constant idiopathic neck pain and left lower scapular pain (greater than 3 months) and was treated based on the principles of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT). Retraction exercises produced centralization of the lower scapular pain to the upper part of the scapula at the initial visit. At the first visit, the performance level on the Cranio-Cervical Flexion Test (CCFT) was ≤20 mmHg before the treatment. At the conclusion of the treatment during which centralization occurred, the CCFT level improved to 24 mmHg. At the second visit, all symptoms were abolished and cervical range of motion (ROM) was fully restored by performing repeated extension in lying from a retracted position with clinician’s traction. The CCFT levels before and immediately after the treatment were 24 and 26 mmHg, respectively. At the third visit (1 week after the initial visit), he noted that all daily activities could be performed without pain. The CCFT level was maintained at 26mmHg. The patient in this study showed immediate improvement in the CCFT through the treatments based on MDT. This suggests a possible link between MDT interventions and motor control of the cervical spine and a need to further investigate this relationship.

Keywords: Assessment, Deep cervical flexors, Neck pain, McKenzie, MDT, Motor control

Background

Motor control deficits associated with neck pain are reported in many studies.1–4 Motor control of cervical muscles is immediately effected by the presence of pain5–8 and altered motor control can remain after nociceptive input has ceased.9 It is hypothesized that motor control deficits can lead to poor control of joint movement, microtrauma, and eventually pain.10–13 Therefore, it is proposed that pain-free treatment is important in the treatment of neck pain14,15 and hypothesized that both pain and neuromotor control may be improved by motor task training.14

In contrast to a neuromotor task training approach, pain behavior is used as the most important criteria for decision making in the treatment algorithm described by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT). MDT uses specific directional loading exercises to alter the location and intensity of pain in order to: (1) classify patient presentations into exclusive subgroups (derangement syndrome, dysfunction syndrome, postural syndrome, and other); and 2) reduce symptoms and increase physical function. The effect of these alterations in pain has never been examined in relation to motor control of the cervical muscles.

MDT is a conservative treatment approach with demonstrated effectiveness for neck pain.16–21 In MDT, the classification of derangement syndrome is the most prevalent subgroup (90%) in patients with neck pain.22 This subgroup is categorized into reducible and irreducible derangement syndromes. Features of the reducible derangement syndrome include: (1) lasting reduction of pain; (2) rapid restoration of motion loss; and (3) directional preference (DP), with and or without centralization, in response to mechanical loading strategies. DP is defined as postures or movements in one direction that centralize, abolish, or decrease symptoms, which may also lead to an improvement in mechanical presentation.23 DP is associated with reduction or abolishment of pain and consequently may be associated with improvement of motor control.

As an assessment of cervical neuromotor control, the Cranio-Cervical Flexion Test (CCFT) is commonly used in clinical practice and research.24 The CCFT is a clinical test of the quality of the deep cervical flexor muscles’ (the longus captis and colli) ability to contract and its validity has been verified in a laboratory setting.25,26 Studies have demonstrated that there is increased activity of superficial muscles and less activity of the deep cervical flexors in those with neck pain, as compared to healthy individuals during the CCFT.2,27–29

The purpose of this case study is to describe a patient with chronic idiopathic neck pain who was classified into the reducible derangement syndrome and demonstrated immediate improvement in the CCFT following treatments based on MDT.24 The patient gave permission to anonymously publish his case report and videos during the CCFT.

Patient Characteristics

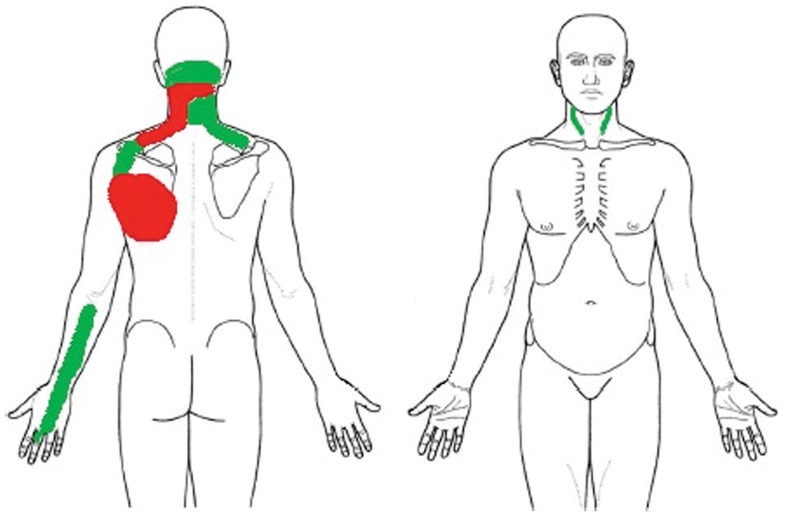

The patient was a 35-year-old male schoolteacher. He presented with intermittent headache and dull pain on the right and front sides of the cervical spine, constant dull pain over the left side of the cervical spine and inferior left scapula, and intermittent pins-and-needles from the left dorsal forearm to the middle finger (Fig. 1). The neck pain commenced, without apparent reason, 4 years ago and the left arm symptoms started about 1 year ago. Three months ago, the neck pain peripheralized to the left scapula and the left arm symptoms peripheralized to the hand. The scapular pain also gradually increased in intensity without apparent reason. At the time of the initial consultation, he was not taking medication and had pain around the lower part of the left scapula (4/10 on the 11-point Numerical Rating Scale where 0 indicated no pain and 10 indicated pain as bad as it can be) and left side of the cervical spine (2/10). He had no previous history of neck pain. He previously undertook massage therapy, which provided temporary relief only. Except for the massage therapy, he had had no other treatment.

Figure 1.

Symptom locations. Red area indicates constant symptom and green area indicates intermittent symptom. At the initial consultation, there were only constant symptoms.

His symptoms were sometimes aggravated by cervical flexion and overhead right arm activities such as throwing. He could not perform throwing with full speed due to aggravation of his symptoms. Sitting for 5 minutes and cervical extension always aggravated his symptoms. Turning the head to either side had no effect. His sleep was often disturbed by pain and he could not use a pillow while sleeping in supine due to symptom aggravation. There were no red flags and he had no history of cervical trauma.

His hobby was riding a road bike (1–4 hours per day). He used a laptop computer at home, where he worked for more than 3 hours with a forward head posture. At the initial consultation, he demonstrated 24/40 on the P4,30 and 28% on the Neck Disability Index (NDI), which rates as mild disability.31 He demonstrated 3·6/10 on the Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS).32 His physical and mental component summary scores on the Outcome Study Short Form 36 version 2 (SF-36v2) were 57·8 and 24·3, respectively. His score on the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptom and Signs (LANSS) was 5/12, which indicates non-neuropathic pain.33 The patient’s goals were to minimize pain and to achieve self-management strategies.

Examination

The CCFT

The CCFT was examined as per the protocol (Stage 2) by Jull et al.24 In brief, a pressure biofeedback device (Stabilizer, Chattanooga, TN, USA) is placed behind the patient’s neck, while the patient is lying in the supine position. The pressure sensor is inflated to a baseline pressure of 20 mmHg. The patient is instructed to perform a slow head nodding action by sliding the head on a bed to sequentially target 5, 2 mm-Hg progressions in pressure increase from the baseline of 20 mmHg to a maximum pressure of 30 mmHg. In addition, the patient must hold the pressure steady for 10 seconds. As a familiarization procedure, the patient is asked to hold at each target pressure for 2–3 seconds before returning to the starting position (20 mmHg). This is repeated with hands-on guidance, and verbal and visual cueing in order to produce the correct movement. Three repetitions are required before the patient is progressed to the next pressure increment (22, 24, 26, 28, and 30 mmHg) with a 10-second rest interval between contractions. The progression was continued until the author (HT) identified one or more of the following failing criteria:

-

1.

cranio-cervical flexion range did not increase with progressive increments of the test;

-

2.

the head was lifted to reach the target pressure;

-

3.

the movement was performed with speed;

-

4.

over-activity of superficial neck muscles was observed;

-

5.

the pressure was increased after return to the starting position.

Video was taken from an anterior posterior perspective and reviewed by two independent assessors, other than the authors, who were experienced in scoring the CCFT. The decisions of the assessors, with respect to the CCFT pressure readings, were blinded from the other assessors. There was perfect agreement between decision-making of the CCFT performance by the three assessors.

Physical assessments

Initially, the patient could not hold a steady pressure at 22 mmHg during CCFT testing and his superficial cervical muscles were trembling during the contraction (Supplementary Material 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/2042618614Y.0000000081.S1). Thus, his CCFT performance level before the treatment was interpreted as ≤20 mmHg.

Following the CCFT testing, physical assessment and treatment based on MDT23 principles were performed by the lead author, who is a credentialed MDT physiotherapist. The patient's sitting posture was poor with a protruded head position. Correction of his posture reduced his neck pain but did not affect the scapular pain. No neurological deficits were detected. The latter included assessment of strength, sensation, upper limb tension tests (1 and 2b), and reflex testing. The patient demonstrated a major motion loss of retraction, moderate loss of cervical extension and left lateral flexion, and minimum loss of head protrusion and cervical flexion, as well as right lateral flexion.

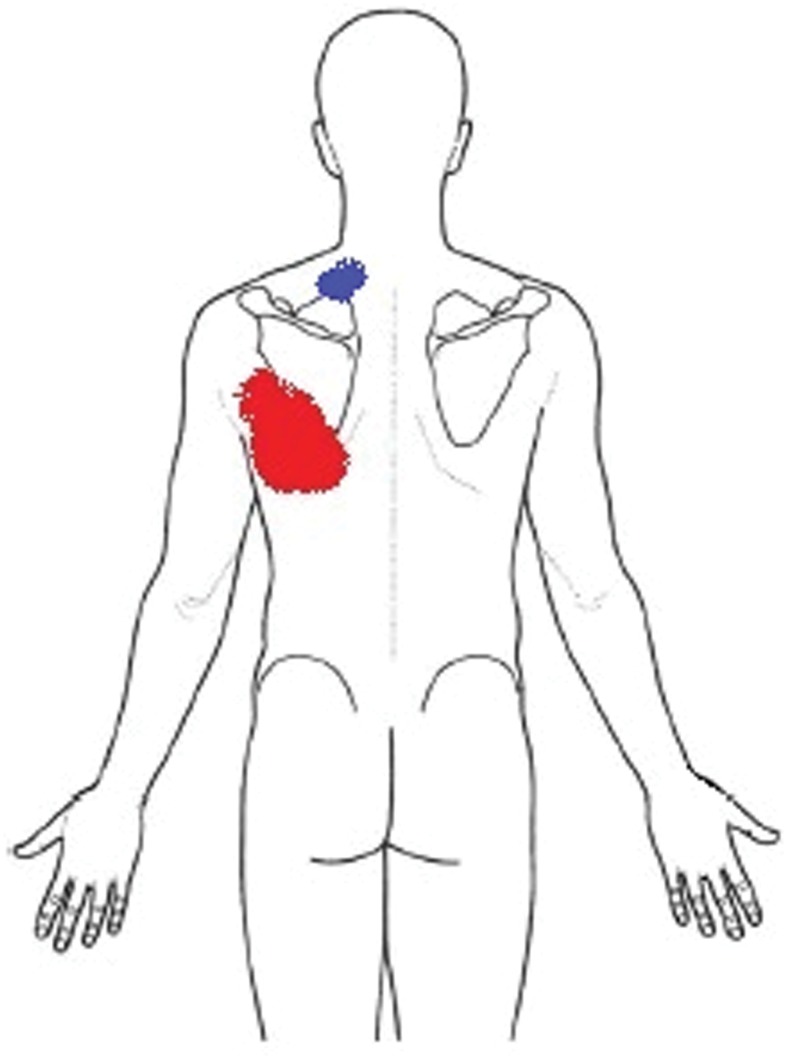

Before beginning repeated movement testing, his symptoms in sitting were located at the left cervical spine (1/10) and the lower part of the left scapula (4/10). Ten repetitions of head protrusion resulted in ‘increase/worse’ (i.e. pain increased during movements and remained worse after the movements) of his scapular pain (5/10). Subsequently, 10 repetitions of head retraction were performed, which resulted in ‘decrease/better’ (i.e. pain reduced during movements and remained better after the movements) scapular pain (2/10). There was no change in symptom location. Twenty repetitions of head retraction with self-overpressure23 did not change his symptoms. It was observed that he could not perform head retraction to the end-range; therefore, head retraction with therapist overpressure23 was applied five times. While performing this, the scapular pain began centralizing towards the midline. After the exercise, scapular pain intensity was increased (5/10) but located more centrally (i.e. centralization). Centralization is a more important finding than pain intensity and, therefore, further investigations with retraction were necessary.34 Thus, 40 repetitions of head retraction with self-over pressure were performed with the therapist guiding the movement. This exercise resulted in further centralization of scapular pain (4/10) and abolishment (i.e. ‘abolish/better’) of the left neck pain (0/10) (Fig. 2), although cervical retraction range of motion (ROM) was still moderately reduced.

Figure 2.

The most distal pain before and after the first session of treatments based on Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. Red area indicates symptom area before the treatment and blue area indicates symptom area after the treatment.

Clinical impressions and reasoning during the initial MDT assessment

Classification into homogeneous sub-groups is an important aspect of MDT. Owing to the presence of constant symptoms in this patient, both posture and dysfunction syndromes were ruled out.23

Pain around the shoulder can be produced by cervical pathologies specifically from the lower cervical levels.35,36 It is a consensus by expert therapists that differentiating cervical pathology from shoulder pathology is of paramount importance37 and cervical assessments based on MDT can be useful to this end.38 Therefore, cervical assessments were completed before starting specific assessments of the shoulder.

The patient’s presentation suggested a neck pathology. First, left scapular pain was peripheralized from the cervical spine. Second, scapular pain is not frequently produced by shoulder pathologies.39 Third, left scapular pain was increased by overhead right arm activities. This is a typical finding in people with cervical pathologies as segmental movements in the cervical spine are produced by active shoulder abduction.40 Peripheralization suggested the presence of a derangement syndrome in the spine,23 which was subsequently confirmed upon completion of the entire examination. The presentation of ‘No effect’ with cervical rotation, and increased symptoms with cervical extension, lying supine and functional flexion activities also indicated the importance of first exploring sagittal loading strategies as a diagnostic procedure.

The patient reported intermittent symptoms over the left arm. His LANSS score was negative and there were no neurological deficits, suggesting no contribution of neural tissues to his symptoms. There was no effect with rotation or left lateral flexion and negative upper limb tension tests, which indicated a low possibility of neuroforaminal space compromising pathologies (e.g. lateral canal stenosis) and mobility related pathology of the nerve tissue (e.g. adherent nerve root in MDT). Therefore, cervical movements that reduce the neuroforaminal space of the cervical spine41 (e.g. cervical extension and rotation) were considered as possible intervention strategies.

The correction of the patient’s head posture reduced his neck pain. Repeated movement testing revealed that head protrusion increased the symptoms. Head retraction reduced the symptoms and produced centralizing symptoms, which fully confirmed the MDT classification of a derangement.23 Head protrusion facilitates substantial extension of the upper cervical spine and moderate flexion of the lower cervical spine.42 In contrast, head retraction accompanies substantial flexion of the upper cervical spine and moderate extension of the lower cervical spine.42 Thus, it was confirmed that mechanical loading in extension at the lower cervical spine was the DP for this patient. The greatest excursion of extension at the lower cervical spine is produced when cervical extension is initiated from a position of head retraction (Ret-Ex).43 As his retraction ROM was still limited even after symptom centralization, it was considered appropriate to further restore retraction, by increasing force with increasing repetitions as a home exercise. This was chosen instead of progressing to the greatest mechanical loading into extension of the lower cervical spine utilizing Ret-Ex.

Home program and reassessment of CCFT

The patient was instructed to repeat end-range retraction with self-over pressure at least 10 times every hour at home. In addition, he was instructed in static and dynamic postural correction focused on avoiding protruded head postures. Following the exercise instructions, the CCFT was examined again. The patient successfully completed the procedures at both 22 and 24 mmHg. However, he demonstrated dial needle flickering and overshooting of his target pressure at 26 mmHg. In addition, the muscles were overactivated. Therefore, his CCFT performance level after the initial treatment session was interpreted as 24 mmHg.

Second consultation (2 days after the initial consultation)

The patient was seen at the same time of day as the initial consultation. He reported that he had performed the prescribed head retraction exercise at least 20 times every hour. He was also mindful of maintaining correct posture during sitting. Retraction ROM had improved to minimal loss. He continued to demonstrate moderate loss of cervical extension and minimal motion loss of left lateral flexion. In relation to the symptoms, the patient reported neither further centralization nor reduction of pain intensity after the initial consultation as a result of performing retraction hourly.

The CCFT was examined again before treatments were undertaken. The patient passed the performance levels at 22 and 24 mmHg. At 26 mmHg, he demonstrated substantial use of the superficial muscles and dial needle flickering and overshooting target pressure. Therefore, the CCFT performance level was interpreted as 24 mmHg.

In the correct sitting posture, he noted pain (4/10) at the upper part of the left scapula only. One Ret-Ex in sitting23 resulted in ‘produce/no worse’ of neck pain and ‘no effect’ of scapular pain. Five repetitions of Ret-Ex resulted in ‘increase/worse’ of scapular pain (6/10) and his cervical extension ROM reduced due to neck pain (6/10). Subsequently, the patient was placed in supine, where he noted 2/10 scapular pain only at rest, and Ret-Ex with clinician traction23 was tested. This resulted in ‘produce/no worse’ of neck pain and the pain intensity was 1/10 during the movement. His scapular pain did not change. Over the course of 20 repetitions of Ret-Ex with clinician traction, his neck and scapular pain decreased. Eventually, supine Ret-Ex produced neither neck nor scapular pain and resulted in ‘abolish/better’ for both neck and scapular pain. In sitting, both retraction and Ret-Ex were restored to full ROM without any pain and 10 repetitions of Ret-Ex resulted in neither production of any symptoms nor reduction in ROM. The patient was asked to perform 10 repetitions of retraction followed by 10 repetitions of Ret-Ex in sitting every 2 hours.

Subsequently, the CCFT was examined again. He could pass all pressure levels up to 26 mmHg, but used the superficial cervical muscles at the level of 28 mmHg. Therefore, his CCFT performance level after the second session of the treatment was interpreted as 26 mmHg.

Third consultation (1 week after the initial consultation)

The patient was seen at the same time of day as the initial consultation. He reported that he had performed the home exercises as prescribed. He reported minimum pain around the cervical spine (1/10) only at the end-range of Ret-Ex during the first few repetitions. Scapular pain was completely abolished and not present during any movement. The residual neck pain abolished on completion of a set of Ret-Ex in sitting. Otherwise, all of his activity was pain-free and neck motion in all directions was fully restored.

In order to assess the stability of the reduced derangement, cervical flexion was tested. With 10 repetitions of flexion and flexion with overpressure,23 there was neither reproduction of pain nor any indication of reduction of cervical extension ROM. These are confirming signs of a fully reduced and stable derangement.23 The patient demonstrated a good understanding of self-treatment and was discharged from treatment at that time. Table 1 summarizes his pain levels during functional tasks before the treatments and at the time of his discharge.

Table 1.

Functional tasks producing pain.

| Before treatments — 24/40 of pain intensity on the P430 | At the time of discharge (thirrd visit) — 7/40 of pain intensity on the P430 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overhead right arm activities (e.g. throwing) | Aggravating symptoms (neck, left scapular, sometimes left forearm-hand) | No pain |

| Sleeping in supine with a pillow | Unable due to an increase of pain (neck, left scapular) | No pain |

| Sitting for 5 minutes | Aggravating pain (neck, left scapular) | No pain |

He demonstrated 7/40 in the P4, 6% in the NDI and 8·2/10 in the PSFS at the third consultation. The improvements were greater than minimum detectable changes (9, P4;44 21%, NDI;45 2, the PSFS32). Additionally, he rated 4 in an 11-point global rating of change scale (−5 = very much worse, 0 = no change, 5 = completely recovered).46

His CCFT was assessed again. He passed all levels up to 26 mmHg, but failed at 28 mmHg due to the use of his superficial cervical muscles during contraction.

Discussion

It has been shown that pain can immediately change motor control of cervical muscles5–8 and that altered motor control can remain after nociceptive input has ceased.9 As a result, pain-free treatment has been recommended in current rehabilitation principles.15 However, the patient in this study showed immediate improvement in the CCFT through treatments based on MDT principles including centralization. The immediate improvement in the CCFT was observed when symptom centralization occurred and further improvement when the derangement was fully reduced.

Studies demonstrate that cervical neuromotor control assessed by the CCFT is improved by specific motor control training that is designed to activate deep cervical flexors without over-activating superficial muscles.47,48 Improvement of performance in the CCFT is limited in typical strength training or in passive mobilization.48,49 Such specific motor control training was not prescribed for this patient. However, it is probable that retraction or Ret-Ex may activate the deep cervical flexors, while minimizing the superficial flexors, more effectively and functionally than typical strength training (e.g. head-lifting or isometric flexion). This may be explained by the fact that cervical retraction exercises produce maximum flexion of the upper cervical spine.42 Thus, retraction and/or Ret-Ex may facilitate deep cervical flexors. In addition, it is known that postural correction in sitting can activate deep cervical flexors and improve the CCFT performance.50,51 Postural correction is included in specific motor control training, as well as MDT interventions.23 Thus, MDT treatments may provide the additional benefit of motor control training for the deep cervical flexors, as apparently shown in this case report. Further investigation with direct measures, including nasopharyngeal electrodes and advanced magnetic resonance imaging, is warranted to investigate neuromotor control ability of deep cervical flexor muscles.

The patient’s CCFT performance improved after both centralization and resolution of the derangement. This suggests that reduction of the derangement may be associated with improvement on the CCFT. Therefore, it is conceivable that a reduction in pain and/or the movement obstruction is associated with enhanced motor control. Cagnie et al.7 demonstrated immediate impact of an experimental muscle pain on motor control of the cervical muscles with the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging and the CCFT. However, further studies are required to enhance understanding of the reasons for altered motor control in people with neck pain, for instance, by using other motor control measures (e.g. onset time of cervical muscle firing during an arm perturbation task1) and by comparing cervical and non-cervical pathologies (e.g. cervicogenic headache and migraine).

This is a retrospective case study and, therefore, it is not possible to identify cause and effect. Improvement of the CCFT was observed in this patient. However, the improvement does not guarantee that there was an actual change in motor control capability since the CCFT is a clinical measure, as opposed to a direct measure of motor control capabilities of the superficial and deep cervical flexors. The construct validity of the CCFT, as a reflection of the quality of the deep cervical flexors’ muscle activity, has been established previously.26 However, it may be possible that CCFT performance is affected by mechanical obstructions within the cervical spine. Thus, the improvement of the CCFT, in this case study, might be due to reduction of mechanical obstructions associated with the derangement. Further research will be required to investigate the relationship between reduction of mechanical obstruction in the spine and changes in motor control capabilities.

It is hypothesized that altered motor control is associated with recurrence of spinal pain52,53 and, therefore, motor control training is considered important. In contrast, MDT approaches the prevention of recurrence of neck pain by educating patients in daily self-mobilizations, posture correction and self monitoring of early signs and symptoms of an impending painful episode. Essentially this is a behavioral modification approach. If MDT treatments result in correction of altered motor control, the logic of the MDT approach to reduce the risk of neck pain recurrence would be enhanced from a bio-physiological perspective. Further studies are required to investigate the relationship between MDT interventions and their possible influence on motor control of the anterior cervical spine musculature.

Conclusion

A patient with neck and scapular pain, who was classified as a reducible derangement syndrome, demonstrated immediate improvement in the CCFT with treatments based on MDT principles. The CCFT improvements were identified immediately after centralization and reduction of the derangement. Future studies are required to investigate a relationship between the MDT approach and motor control of the cervical muscles.

Disclaimer Statements

Contributors The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Julia M. Treleaven and Dr Leanne M. Hall for evaluating performance in the Cranio-Cervical Flexion Test as independent blind assessors.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest The authors have no financial affiliation (including research funding). One of the authors (HT) has no conflict of interest. Another author (SH) is an instructor of the International McKenzie Institute. He provides educational workshops about Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy for which he receives a teaching fee.

Ethics approval This is a retrospective case report. Therefore, neither Institutional Review Board approval of the study protocol nor trial registry is not relevant. However, the patient reported in this case study was informed that data of the patient would be submitted for publication in an anonymous fashion and the patient agreed to do so.

References

- 1.Falla D, Jull G, Hodges PW. Feedforward activity of the cervical flexor muscles during voluntary arm movements is delayed in chronic neck pain. Exp Brain Res. 2004;157:43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falla DL, Jull GA, Hodges PW. Patients with neck pain demonstrate reduced electromyographic activity of the deep cervical flexor muscles during performance of the craniocervical flexion test. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schomacher J, Farina D, Lindstroem R, Falla D. Chronic trauma-induced neck pain impairs the neural control of the deep semispinalis cervicis muscle. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:1403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindstrom R, Schomacher J, Farina D, Rechter L, Falla D. Association between neck muscle coactivation, pain, and strength in women with neck pain. Man Ther. 2011;16:80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falla D, Farina D, Graven-Nielsen T. Experimental muscle pain results in reorganization of coordination among trapezius muscle subdivisions during repetitive shoulder flexion. Exp Brain Res. 2007;178:385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cagnie B, O’Leary S, Elliott J, Peeters I, Parlevliet T, Danneels L. Pain-induced changes in the activity of the cervical extensor muscles evaluated by muscle functional magnetic resonance imaging. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cagnie B, Dirks R, Schouten M, Parlevliet T, Cambier D, Danneels L. Functional reorganization of cervical flexor activity because of induced muscle pain evaluated by muscle functional magnetic resonance imaging. Man Ther. 2011;16:470–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falla D, Farina D. Neuromuscular adaptation in experimental and clinical neck pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker K, Larsson AK, Oknelid S, Hodges P. Similar alteration of motor unit recruitment strategies during the anticipation and experience of pain. Pain. 2012;153:636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodges PW, Tucker K. Moving differently in pain: a new theory to explain the adaptation to pain. Pain. 2011;152:S90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges PW. Pain and motor control: From the laboratory to rehabilitation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21:220–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:390–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudreau SA, Farina D, Falla D. The role of motor learning and neuroplasticity in designing rehabilitation approaches for musculoskeletal pain disorders. Man Ther. 2010;15:410–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jull G, Sterling M, Falla D, Treleaven J, O’Leary S. Whiplash, headache, and neck pain: research-based directions for physical therapies. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008. p. 191–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjellman G, Öberg B. A randomized clinical trial comparing general exercise, McKenzie treatment and a control group in patients with neck pain. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh P, Gupta K. Comparative study of a structured progressive exercise program and McKenzie protocol in individuals with mechanical cervical spine pain. Physiother Occup Ther J. 2012;5:11–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffett JK, Jackson DA, Gardiner ED, Torgerson DJ, Coulton S, Eaton S, et al. Randomized trial of two physiotherapy interventions for primary care neck and back pain patients: ‘McKenzie’ vs brief physiotherapy pain management. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:1514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kongsted A, Qerama E, Kasch H, Bendix T, Bach FW, Korsholm L, et al. Neck collar, ‘act-as-usual’ or active mobilization for whiplash injury? A randomized parallel-group trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenfeld ME, Seferiadis A, Carlsson J, Gunnarsson R. Active intervention in patients with whiplash-associated disorders improves long-term prognosis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:2491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzy G, Frańczuk B, Krańkowska A. A clinical trial comparing the McKenzie method and a complex rehabilitation program in patients with cervical derangement syndrome. J Orthop Trauma Surg Relat Res. 2011;2:32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefford C. McKenzie classification of mechanical spinal pain: profile of syndromes and directions of preference. Man Ther. 2008;13:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenzie R, May S. The cervical and thoracic spine. Mechanical diagnosis and therapy. 2nd ed. Waikanae: Spinal Publications; 2006. p. 86, 231,, 238,, 242,, 296–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jull GA, O’Leary SP, Falla DL. Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falla D, Jull G, O’Leary S, Dall’Alba P. Further evaluation of an EMG technique for assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006;16:621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falla DL, Jull G, Dall’Alba P, Rainoldi A, Merletti R. An electromyographic analysis of the deep cervical flexor muscles in performance of craniocervical flexion. Phys Ther. 2003;83:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jull GA. Deep cervical flexor muscle dysfunction in whiplash. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2000;8:143–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jull G, Kristjansson E, Dall’Alba P. Impairment in the cervical flexors: a comparison of whiplash and insidious onset neck pain patients. Man Ther. 2004;9:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J. Characterization of acute whiplash-associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spadoni GF, Stratford PW, Solomon PE, Wishart LR. The development and cross-validation of the P4: a self-report pain intensity measure. Physiother Can. 2003;55:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14:409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratford PW, Gill C, Westaway MD, Binkley JM. Assessing disability and change on individual patients: a report of a patient specific measure. Physiother Can. 1995;47:258–62. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett M. The LANSS Pain Scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001;92:147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.May S, Aina A. Centralization and directional preference: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2012;17:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slipman CW, Plastaras C, Patel R, Isaac Z, Chow D, Garvan C, et al. Provocative cervical discography symptom mapping. Spine J. 2005;5:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aprill C, Dwyer A, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. II: A clinical evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15:458–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.May S, Greasley A, Reeve S, Withers S. Expert therapists use specific clinical reasoning processes in the assessment and management of patients with shoulder pain: a qualitative study. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menon A, May S. Shoulder pain: differential diagnosis with mechanical diagnosis and therapy extremity assessment — a case report. Man Ther. 2013;18:354–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bayam L, Ahmad MA, Naqui SZ, Chouhan A, Funk L. Pain mapping for common shoulder disorders. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2011;40:353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takasaki H, Hall T, Kaneko S, Iizawa T, Ikemoto Y. Cervical segmental motion induced by shoulder abduction assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takasaki H, Hall T, Jull G, Kaneko S, Iizawa T, Ikemoto Y. The influence of cervical traction, compression, and spurling test on cervical intervertebral foramen size. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1658–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ordway NR, Seymour RJ, Donelson RG, Hojnowski LS, Thomas Edwards W. Cervical flexion, extension, protrusion, and retraction a radiographic segmental analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takasaki H, Hall T, Kaneko S, Ikemoto Y, Jull G. A radiographic analysis of the influence of initial neck posture on cervical segmental movement at end-range extension in asymptomatic subjects. Man Ther. 2011;16:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spadoni GF, Stratford PW, Solomon PE, Wishart LR. The evaluation of change in pain intensity: a comparison of the P4 and single-item numeric pain rating scales. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pool JJ, Ostelo RW, Hoving JL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Minimal clinically important change of the Neck Disability Index and the Numerical Rating Scale for patients with neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:3047–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falla D, O’Leary S, Farina D, Jull G. The change in deep cervical flexor activity after training is associated with the degree of pain reduction in patients with chronic neck pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jull GA, Falla D, Vicenzino B, Hodges PW. The effect of therapeutic exercise on activation of the deep cervical flexor muscles in people with chronic neck pain. Man Ther. 2009;14:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lluch E, Schomacher J, Gizzi L, Petzke F, Seegar D, Falla D. Immediate effects of active cranio-cervical flexion exercise versus passive mobilisation of the upper cervical spine on pain and performance on the cranio-cervical flexion test. Man Ther. 2014;19:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beer A, Treleaven J, Jull G. Can a functional postural exercise improve performance in the cranio-cervical flexion test? — A preliminary study. Man Ther. 2012;17:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Falla D, O’Leary S, Fagan A, Jull G. Recruitment of the deep cervical flexor muscles during a postural-correction exercise performed in sitting. Man Ther. 2007;12:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arendt-Nielsen L, Falla D. Motor control adjustments in musculoskeletal pain and the implications for pain recurrence. Pain. 2009;142:171–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hides JA, Jull GA, Richardson CA. Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for first-episode low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:E243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]