Abstract

Objective

Determine the effect of perineal lacerations on pelvic floor outcomes including urinary and anal incontinence, sexual function and perineal pain in a nulliparous cohort with low incidence of episiotomy.

Methods

Nulliparous women were prospectively recruited from a midwifery practice. Pelvic floor symptoms were assessed with validated questionnaires, physical examination and objective measures in pregnancy and 6 months postpartum. Two trauma groups were compared, those with an intact perineum or only 1st degree lacerations and those with 2nd, 3rd or 4th degree lacerations.

Results

448 women had vaginal deliveries. 151 sustained second degree or deeper perineal trauma and 297 had an intact perineum or minor trauma. 336 (74.8%) presented for 6-month follow-up. Perineal trauma was not associated with urinary or fecal incontinence, decreased sexual activity, perineal pain, or pelvic organ prolapse. Women with trauma had similar rates of sexual activity however they had slightly lower sexual function scores (27.3 vs. 29.1, p=0.01). Objective measures of pelvic floor strength, rectal tone, urinary incontinence, and perineal anatomy were equivalent. The subgroup of women with deeper (> 2cm) perineal trauma demonstrated increased likelihood of perineal pain (15.5 vs. 6.2 %) and weaker pelvic floor muscle strength (61.0 vs. 44.3%); p=0.03 compared to women with more superficial trauma Conclusion: Women having second degree lacerations are not at increased risk for pelvic floor dysfunction other than increased pain, and slightly lower sexual function scores at 6 months postpartum.

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth have been associated with altered pelvic floor function, including increased rates of urinary and anal incontinence, sexual dysfunction and perineal pain, however it remains unclear if the relationship persists in spontaneous birth without operative vaginal delivery, episiotomy or significant perineal lacerations. A meta-analysis of mode of delivery demonstrated an increased likelihood of stress urinary incontinence for women who were at one year or more postpartum from a vaginal delivery compared to cesarean delivery (Odds ratio 1.85 ;95% CI 1.56-2.19).1. The risk of future pelvic organ prolapse is also increased for vaginal, compared to cesarean births. 2-4 Postpartum sexual dysfunction and dyspareunia have been associated with vaginal birth complicated by perineal laceration and operative vaginal delivery, however cesarean delivery does not appear to result in improved sexual function compared to spontaneous vaginal delivery.5-7 Anal incontinence is strongly associated with the occurrence of anal sphincter laceration;8 however, vaginal birth without sphincter laceration does not increase the rate of anal incontinence compared to cesarean delivery.9,10 The majority of women who give birth vaginally sustain at least minor lacerations,11 however, the impact of perineal lacerations on pelvic floor function has not been well studied.

Postpartum women and maternity care providers often assume that an intact perineum implies minimal pelvic floor injury. Vaginal birth in developed nations has been accompanied by high rates of operative vaginal delivery and elective episiotomy 9, which are the primary factors associated with severe perineal trauma as well as pelvic floor dysfunction.12 Because of the high rates of these interventions in vaginal birth, the effects of spontaneous birth without episiotomy or operative delivery on pelvic floor function have not been studied adequately. In an earlier study, we found no association between the presence of second-degree perineal lacerations and pelvic floor dysfunction; however, that study was limited by lack of a pre-delivery assessment of pelvic floor function, inclusion of multiparous women, short term follow-up and the inability to assess the depth of the second-degree lacerations.13

The primary aim of this study was to determine the effect of perineal lacerations on postpartum pelvic floor outcomes including urinary and anal incontinence, sexual function and perineal pain in a low risk nulliparous population with a low utilization of operative vaginal delivery and a very low incidence of episiotomy. A secondary aim was to determine if the depth of second-degree laceration was associated with pelvic floor functional changes.

Methods

We have previously reported differences in pelvic floor outcomes between women who did and did not enter the second stage of labor,14 as well as perineal ultrasound measurements from this prospective cohort.15 In brief, nulliparous midwifery patients were recruited from 2006-2011 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Eligibility criteria were age >18 years of age, ability to speak and read either English or Spanish, singleton gestation, and absence of serious medical problems. Women were enrolled during pregnancy into the study from the antenatal midwifery clinics at a gestational age of ≤ 36 completed weeks. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico, and all women gave written consent.

Midwifery patients underwent physical exam early in their prenatal care, which was usually in first or early second trimester. They provided functional data in early (first or second trimester) and late (third trimester) pregnancy and again at 6 months postpartum. Physical exam data collected included Pelvic Floor Quantification Exams (POP-Q)16, assessment of pelvic floor muscle strength using the Brinks scale17, a paper towel test for urinary incontinence18 and visual inspection of the perineum., Women underwent rectal exam with quantification of the sphincter strength and tone with a modified Brinks scale. Nurse-midwife examiners underwent training with live models prior to and annually during the study; in addition, to ensure standardization of measurements, seventeen exams were repeated with two examiners to determine inter-rater reliability.

At 6 months postpartum, women completed a paper towel test. With a full bladder, women were asked to cough three times within a ten second time span, with the paper towel applied to the perineum..18. Functional data collected included quality of life and symptom severity scales: the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI)19,20, the Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis 19, the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire 21,22 and its subscales, the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (, the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire and the Colorectal Anal Impact Questionnaire , the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Scale 23, the Present Pain Intensity Scale 24 and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).25,26 Any UI was defined as ISI scores > 0; moderate to severe UI was defined as ISI scores ≥ 320. Any anal incontinence (flatus, liquid or solid stool) was defined as a Wexner score > 0; fecal incontinence was defined as an affirmative answer to the questions regarding leakage of liquid or solid stool. Women were compensated $50.00 at the six-month visit for travel and babysitting costs, and an additional $25.00 after ultrasound exams. If women did not present for appointments, they were phoned to reschedule. If they did not keep the second appointment, women were mailed questionnaires.

Intrapartum data collected at delivery included maternal, fetal, and labor characteristics. The UNM nurse midwives received extensive training in the identification and anatomic mapping of perineal and vaginal lacerations which has been previously reported.11,13,27,28 The attendant midwife recorded perineal trauma immediately after delivery on standardized forms Severity of trauma was categorized for perineal lacerations into first, second, third and fourth degree lacerations.. Women without any trauma were described as intact. The depth of second degree perineal lacerations were measured29 from the posterior margin of the genital hiatus to the laceration apex on each side (right (X) and left (Y)) and the average was recorded as the laceration length {(X + Y)/2} as described by Nager. Trauma was dichotomized into perineal trauma (second, third or fourth degree lacerations) compared to intact/minor trauma (intact or had only first-degree perineal or non-perineal trauma) for the primary analysis. For secondary analysis, women with deep second degree perineal lacerations that were > 2cm or had anal sphincter lacerations were compared to women with an intact perineum, first degree perineal, vaginal lacerations and/or second degree lacerations that were ≤ 2.0 cm in depth. A second observer was asked to assess the perineum for lacerations greater than or equal to a second-degree laceration. Perineal trauma suturing was standardized using an anatomic approach as previously described,30 and all midwives participated in annual laceration repair workshops.

For the parent study examining pelvic floor outcomes based on mode of delivery, we aimed to recruit 630 nulliparous women from the nurse-midwifery clinics and anticipated that 20% of women would not deliver with the midwifery service. In addition, 50 midwife patients were expected to deliver by cesarean. With an assumption of 75% follow-up, we estimated that 375 women experiencing vaginal birth would give data at 6 months postpartum. The parent study had adequate power to test for prevalence of anal incontinence, urinary incontinence and sexual activity at six-month postpartum follow-up between mothers who delivered vaginally and by cesarean delivery.14 For our subgroup analysis of women having a vaginal birth our sample size at six months was 217 women with an intact perineum or minimal trauma and 118 in the perineal trauma group. This was adequate to detect differences between groups of 16% for AI, 6.5% for fecal incontinence, 16.5% for urinary incontinence (ISI) and 13% for lack of sexual activity with 80% power and alpha =0.05 retrospective calculations. Descriptive statistics were used to compare groups at baseline and follow-up; categorical data were compared using Fischer’s exact test or chi-square analyses where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using t tests. Wilcoxon rank sums were used for nonparametric analysis when a non-normal distribution was determined to be present for the variables.

Results

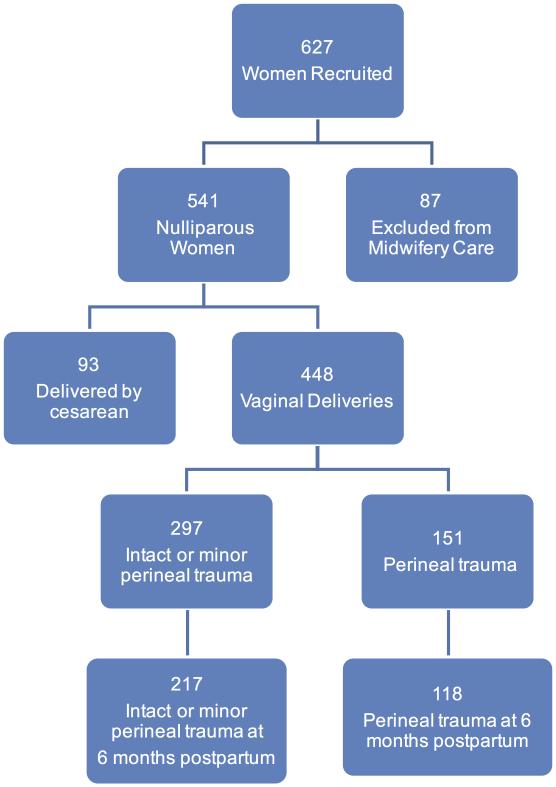

Of 627 women recruited, 541 delivered with the midwifery service. Eighty-six women left midwifery care secondary to early pregnancy loss, relocation, insurance changes or medical complications of pregnancy. Ninety-three women delivered by cesarean section were excluded, leaving 448 women with vaginal deliveries (Figure 1). One hundred and fifty-one women sustained perineal trauma (129 second degree, 19 third degree s, and 3 fourth degree perineal lacerations) and 297 women delivered with an intact genital tract or with minor trauma (210 and 87 women, respectively). Of the 129 second degree lacerations; 52 were greater than 2 cm in depth, 39 were ≤ 2 cm, and 38 did not have the depth recorded.

Figure 1.

Study Participants

Of the 448 women who delivered vaginally, 335 (74.8%) presented for 6-month follow-up and were included in the primary analysis as Perineal trauma and Intact/minor groups. The secondary analysis compared the 61 women with deep lacerations (2nd degree >2cm, 3rd and 4th degrees) to the 245 women who were intact or had nondeep trauma and returned for six-month follow-up. The population that did not return for follow-up was slightly younger (22.5 vs. 24.4years; p<0.001) and reported fewer years of education (13.1vs. 14.1years; p<0.001) but did not differ with regard to antenatal assessment of urinary or anal incontinence, sexual activity, or perineal pain. A greater proportion of the group lost to follow-up received oxytocin in labor (56.8 vs. 44.9%; p=0.04); however, the groups did not differ in other labor or childbirth variables.

Few women underwent operative vaginal delivery for a nulliparous group; 25 vacuum deliveries and 1 forceps delivery represented 5.8% of deliveries. Only 8 (2%) women underwent episiotomy. Of the women who sustained second-degree lacerations or greater (77/129), 60% had a second observer to verify the extent of the laceration; all but one of the second observers agreed with the second-degree diagnosis. During the antepartum measurement of the perineal body and genital hiatus, 17 women underwent repeat exams for inter-rater reliability testing of the POP-Q exam; agreement between examiners was high (82% complete agreement) for prolapse stage. All POP-Q points were within 1 cm of agreement for 82% of measures, and perineal body measurements were within 0.5 cm for 82% of measures.

Demographics and obstetric characteristics

Women experiencing perineal trauma were older (25. vs. 23.0; p<0.001), had more years of education (14.9 vs. 13.3; p< 0.001)), and were slightly taller (64.7 vs. 63.7 cm; p<. 001) (Table1). Hispanic women were more likely to experience perineal trauma than non-Hispanic white women (53.6% vs 37.7%, p <0.001). Higher mean birth weight was associated with increased likelihood of perineal trauma (3304 vs. 3171 gm; p=0.001) and having a small for gestational age (SGA) infant was protective with 2% of newborns being SGA in the perineal trauma group compared to 7.1% in the group with minor trauma or an intact perineum (p=0.03). Of the labor variables, the length of active second stage (95 vs. 61 3 minutes; p<0.0001) and an infant delivering occiput posterior or transverse (6.0% vs. 1.6%; p=0.02) were associated with increased likelihood of perineal trauma and delivery between contractions was protective. The groups did not differ in antenatal assessments of urinary and anal incontinence, or perineal pain (all P >.0.05). The group who delivered with intact perineum or minor trauma had higher antenatal sexual function based on Female Sexual Function Index scores (26.9 vs 25.3; p=0.03) and was more likely to have been sexually active in the third trimester (82.4 vs 65.1%; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics, antenatal pelvic floor anatomy function, and labor care measures in women who sustained perineal trauma and those who delivered intact or who had minor trauma, University of New Mexico 2006-2011

| Maternal characteristics | Intact/Minor laceration N=297 % or mean+/−SD |

Perineal trauma (≥ 2nd degree laceration) n=151 % or mean+/−SD |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23.0+/−4.4 | 25.7+/−5.3 | <0.0001 |

| Years of education | 13.3+/−2.4 | 14.9+/−2.7 | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index | 24.6+/− 5.6 | 24.8+/−4.8 | 0.75 |

| Weight Gain in pregnancy (lb.) |

35.5+/−13.1 | 35.5+/−14.8 | 0.99 |

| Race | |||

| NonHispanic White | <0.01* | ||

| 50.5% | 33.8% | ||

| Native American | 5.4% | 6.6% | |

| Other | 6.4% | 6.0% | |

| Tobacco Use | 6.4% | 7.3% | 0.84 |

| Antenatal Pelvic Floor Anatomy (at prenatal presentation for care) | |||

| Perineal Body Length cm | 3.6 +/− 0.8 | 3.7 +/− 0.8 | 0.28 |

| Genital Hiatus (rest) cm | 2.5+/− 0.8 | 2.4+/− 0.8 | 0.36 |

| Genital Hiatus (strain) cm | 2.7+/− 0.8 | 2.6+/− 0.8 | 0.40 |

| Antenatal Pelvic Floor Function (3rd Trimester) | |||

| Any Anal Incontinence | 15.7% | 15.2% | 1.00 |

| Any Urinary Incontinence | 72.1% | 74.1% | 0.73 |

| ISI scores among those with any incontinence |

2.2 +/− 1.4 | 2.5+/− 1.7 | 0.16 |

| Female Sexual Function Index Score |

26.9+/− 5.8 | 25.3+/− 5.9 | 0.03 |

| Sexually active | 82.4% | 65.1% | <0.001 |

| Perineal pain VAS Score | 0.9+/− 1.6 | 0.9+/− 1.6 | 0.99 |

| Labor birth outcomes | |||

| SGA | 7.1% | 2.0% | 0.03 |

| Epidural | 60.9% | 58.7% | 0.64 |

| Oxytocin | 45.2% | 53.0% | 0.12 |

| Occiput posterior/transverse | 1.7% | 6.0% | 0.02 |

| Delivered During Contraction | 26.3% | 37.8% | 0.03 |

| Length of active 2nd stage Minutes |

60.6 +/− 48.3 | 94.8 +/−81.4 | <.0001 |

| Birth Weight gms | 3171+/−438 | 3304+/−384 | 0.001 |

VAS: analogue scale

A Comparison of NHW to HW is <0.001 while all other comparisons are NS

SGA; Small for gestational age, ISI Incontinence Severity Index;

Urinary and anal incontinence

Perineal trauma was not associated with urinary incontinence as measured on patient questionnaires at 6 months postpartum or as objectively by the paper towel test (Table 2). These outcomes were unchanged when comparing the women with deeper lacerations (2nd > 2cm, 3rd and 4th degree) to all other women. A higher proportion of women with perineal trauma reported at least one incident of anal incontinence (includes flatus) on the Wexner scale (57.8 vs. 45.3%, p=0.03). The proportion of women with fecal incontinence did not differ between the trauma groups. When women with perineal lacerations were split into three groups (intact /first degree, 2nd versus 3rd/4th lacerations) reports of anal incontinence increased from 45% to 55% to 72% respectively. A pairwise comparison between the three groups using Fischer’s exact test demonstrated that rates of anal incontinence only varied between women with an intact perineum/1st degree tear and women with 3rd or 4th degree lacerations (p=0.047). Women with perineal trauma and any anal incontinence did not have worse symptoms based on the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Scale score or a greater effect on their quality of life based on Colorectal Anal Impact Questionnaire compared to women without perineal trauma.

Table 2.

Perineal trauma and six month postpartum pelvic floor outcomes, University of New Mexico 2006-2011

| Outcome measure | Intact/ Minor laceration N=217 % or Mean+−SD |

Perineal trauma (≥ 2nd degree laceration) N=118 % or Mean+−SD |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anal and Urinary Incontinence | |||

| Any Anal incontinence (Wexner≥1) | 45.3% | 57.8% | 0.03 |

| Fecal incontinence response, positive response on Wexner |

7.1% | 10.3% | 0.30 |

| Wexner scores among those with any anal incontinence Fecal Incontinence Index (N=163) |

1.9+/− 1.9 | 2.1+/− 1.7 | 0.44 |

| Any urinary incontinence ISI>0 | 53.1% | 59.8% | 0.25 |

| Incontinence Severity Index (ISI) among those with any urinary incontinence on ISI (N=183) |

1.7+/− 1.0 | 1.8+/−1.23 | 0.80 |

| Sexual Function and Perineal Pain | |||

| Sexually active | 87.8% | 87.1% | 0.86 |

| Female Sexual Function Index | 29.1+/− 5.1 | 27.3+/− 5.8 | 0.01 |

| Individual Responses on Female Sexual Function Index | |||

| Desire | 3.9+/−1.27 | 3.7+/−1.20 | 0.11 |

| Arousal | 4.4+/−1.77 | 3.8+/−1.86 | <0.01 |

| Lubrication | 4.6+/−1.87 | 4.2+/−2.15 | 0.09 |

| Orgasm | 4.4+/−1.91 | 3.9+/−2.10 | 0.07 |

| Satisfaction | 4.8+/−1.41 | 4.5+/−1.44 | 0.05 |

| Pain | 5.2+/−1.04 | 4.8+/−1.40 | <0.01 |

| Perineal Pain Visual Analog Scale | 0.13+/− 0.86 | 0.31+/− 1.4 | 0.21 |

| Perineal pain now; None (PPI=0) | 93.4% | 90.4% | 0.51 |

| Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Muscle Function | |||

| Total vaginal length (cm) | 7.4+/− 1.4 | 7.3+/− 1.5 | 0.68 |

| Perineal Body Length (cm) | 3.3+/− 0.8 | 3.3 +/− 0.8 | 0.44 |

| Genital Hiatus at rest (cm) | 2.7+/− 0.7 | 2.8+/−0.7 | 0.33 |

| Genital Hiatus with strain (cm) 3.3+/−0.8 3.4+/−0.8 0.48 | |||

| IAS not intact on transperineal ultrasound (N=291) |

7.0 % | 15.1% | 0.04 |

| External anal sphincter not intact on transperineal ultrasound (N=289) |

0.0% | 1.90% | 0.13 |

| Kegel strength (none/weak) | 44.3% | 52.3% | 0.20 |

| Rectal resting tone (none/weak) | 3.7% | 10.4% | 0.07 |

| Rectal squeeze present | 41.9% | 42.1% | 1.0 |

| Paper towel test ( (wet) | 20% | 14.4% | 0.28 |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse Stage | 0.87 * | ||

| 0 | 13.7% | 15.3% | |

| 1 | 66.4% | 62.1% | |

| 2 | 19.5% | 22.2% | |

| 3 | 0.5% | 0.0 % | |

| Pelvic Organ prolapse impact score among women with Stage 2 or greater pelvic organ prolapse (N=76) |

5.0+/− 14.7 | 1.1+/−3.4 | 0.11 |

ISI: Incontinence Severity Index; PPI: Present pain Intensity IAS: Internal Anal Sphincter.

Jonckheere-Terpstra test

Pelvic floor strength and anatomy

On physical examination at 6 months postpartum there was no difference in the presence of pelvic organ prolapse as measured by POP-Q stages or individual POP-Q points. At 6 months, objective analysis of pelvic floor strength on Kegel exam, as well as rectal resting and squeeze tone did not differ between the groups. Perineal body and genital hiatus length were also similar. On transperineal ultrasound (n=291) all women in the intact or minor trauma group had an intact external anal sphincter and only 1.9% of the perineal trauma group has a defect in the external anal sphincter.. A greater proportion of women in the perineal trauma group had a nonintact internal anal sphincter (15.1 vs. 7.0 %, p=0.04) on transperineal ultrasound (n-289). In the subgroup analysis of deeper lacerations women with deep trauma were more likely to have weaker pelvic floor muscle strength as measured by the Brinks scale for Kegel (61.0 vs. 44.3%; p=0.03). In an additional analysis (not shown) in which the women with 3rd and 4th degree lacerations were excluded from the deep trauma group, the finding of weaker Kegel muscle strength (53.7% vs 44.3%; p=0.07) was still present, although no longer statistically significant.

Pain and Sexual Function

The presence of perineal pain at 6 months did not differ significantly when assessed by a Likert scale or visual analog scale for the primary analysis groups. In the subgroup analysis of women with deep perineal trauma a greater proportion reported perineal pain at 6 months than women with less severe trauma (15.5 vs. 6.2%; p=0.01), however the severity of pain was not different between groups (0.38 vs. 0.12; p=0.19). When women with 3rd and 4th degree lacerations were excluded from the deep trauma group the findings of a greater proportion of women with pain at 6 months (17.8% vs 6.2%, p=0.04) was still present.

Perineal trauma was not associated with a difference in sexual activity at six months postpartum, however women with perineal trauma had lower scores on the Female Sexual Function Index indicating poorer sexual function (27.3 vs 29.1; p=0.01) The differences were attributable to lower scores in the FSFI domains of arousal, pain and satisfaction The findings of lower FSFI scores was also present in subgroup analysis of deeper lacerations based on domains of arousal and pain.

Discussion

We found that perineal trauma in a study cohort with low rates of operative vaginal delivery and episiotomy is associated with minimal pelvic floor dysfunction at six months postpartum. Rates of urinary and anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and sexual activity were similar between trauma groups other than an increased incidence of anal incontinence attributable to the subgroup with 3rd and 4th degree lacerations. There was a small decrease in sexual function scores in the perineal trauma group that is unlikely of clinical significance. Although likelihood of pain was greater with trauma overall levels of perineal pain were low. Objective incontinence measures including rectal tone, Brink’s pelvic floor muscle strength, the paper towel test were also similar. Perineal measurements (Genital Hiatus and Perineal Body on the POPQ examinations) were not different between groups. Women can be reassured that spontaneous perineal trauma is unlikely to result in adverse pelvic floor functional outcomes at 6 months postpartum.

An intact perineum after childbirth remains a desirable obstetrical outcome as women report a decrease in immediate and six month postpartum pain compared with women having spontaneous lacerations or an episiotomy.27,31 Similar to other researchers, we found that some patient characteristics including age, race, height, and education were associated with perineal trauma. Higher rates of sexual activity and higher sexual function scores on the Female Sexual Function Index in the 3rd trimester were associated with less perineal trauma. Although an association between antenatal sexual function and less perineal trauma has not been previously reported, perineal massage in the third trimester is associated with a decrease in perineal trauma for nulliparous women.32 Newborn weight is associated with perineal trauma; avoiding macrosomia and excessive prenatal weight gain are also advisable to decrease the incidence of cesarean delivery.33 A prolonged second stage is associated with occurrence of perineal trauma; however, given the association of operative vaginal delivery and episiotomy with anal sphincter trauma, these interventions are not appropriate to shorten the second stage unless indications are present. Delivering between uterine contractions was protective of the perineum confirming a similar finding from the INTACT study at our institution.11 The association between occiput posterior presentation and perineal trauma suggests potential benefit from manual rotation to occiput anterior which has been previously demonstrated to decrease the incidence of cesarean delivery and severe perineal lacerations.34

Strengths of our study include following women prospectively during pregnancy and through the 6-month postpartum visits, multidimensional assessment of pelvic floor function, and inclusion of physical exam findings and functional questionnaire data. Limitations include the primary assessment of pelvic floor function occurring at six months while the timing of onset of pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence may be many years after delivery. We included measurements of subtle pelvic floor dysfunction: including any anal incontinence including loss of flatus, any urinary incontinence, pelvic muscle strength, rectal tone and any change in pelvic floor anatomy demonstrable by the POP-Q to potentially identify women at increased future risk. The group with an intact perineum or minor trauma had higher sexual function scores in the 3rd trimester and postpartum differences may be at least partially attributable to the baseline differences. In addition, 38 (29%) of subjects did not have the depth of their perineal lacerations measured. The measurement of the depth of the laceration was done to decrease the likelihood that clinically trivial second degree lacerations were affecting our ability to detect an effect of deeper second degree lacerations. We used the measurement technique developed by Nager29 and second examiners to increase the reliability of these measurements, however it is unknown what depth might have clinical importance and we chose a 2cm cutoff to dichotomize the groups. Our power to detect differences in the subgroup with deep second degree perineal trauma was limited by the smaller number of women.

Our study population had a low incidence of episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery for nulliparous women. The national operative vaginal delivery rate for all women in 2012 was 3.40% of which 2.79% were vacuum assisted and 0.61%, forceps35; in 1990, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 9.01%, which included a forceps rate of 5.11%. The rate of episiotomy decreased from 60.9% in 1979 to 11.1 % in 2009. 36, 30,37. The frequency of episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery in our cohort is consistent with current recommendations against routine use of episiotomy and the national fall in operative vaginal delivery rates; therefore, our study results are applicable to current obstetric practice. Although the study population was a healthy cohort of nulliparous patients cared for by nurse midwives, similar rates of episiotomy and operative delivery are found in our University of New Mexico patients managed by obstetrician/gynecologists and family physicians.38

Midline episiotomy is the prevalent practice in the United States, and its association with anal sphincter laceration has been shown in numerous studies. Many other countries predominantly perform medial lateral episiotomy; our results are not applicable to these women as medial lateral episiotomy has been shown to produce different anatomic outcomes with regards to anal sphincter and anterior vaginal trauma 39,40 Postpartum pelvic floor function studies are needed including comparison groups of women sustaining midline vs. medial lateral episiotomy and with sutured vs. unsutured 2nd degree lacerations.

Prevention of second-degree lacerations remains a desirable childbirth outcome due to the increased pain secondary to the lacerations and the prevention anal sphincter lacerations is beneficial due to the strong association with future anal incontinence. Women having second degree lacerations, even when the depth is greater than 2 cm, can be reassured that they are not at increased risk for urinary or anal incontinence, delayed return of sexual activity or measurable changes in perineal and vaginal anatomy at 6 months postpartum. Although women with these lacerations are more likely to have perineal pain at six months, eighty-two percent will be free of pain.

In conclusion, we found that spontaneous perineal trauma was not associated with increased risk of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction based on a comprehensive assessment of functional and anatomic outcomes. Delivery between contractions, manual rotation from occiput posterior position, and sparse use of episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery may contribute to lower rates of perineal trauma.

Table 3.

Deep Perineal Trauma and Pelvic Floor Outcomes, University of New Mexico, 2006-2011

|

Outcome measure |

Intact or non-deep trauma N=245 % or mean+/−SD |

Deep perineal trauma N=61 (>2cm into perineal body)% or mean+/−SD |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anal and Urinary Incontinence | |||

| Any anal incontinence (Wexner≥1) | 46.7% | 59.3% | 0.11 |

| Fecal incontinence, positive response on Wexner |

7.9% | 8.5% | 0.80 |

| Wexner scores among those with any anal incontinence Fecal Incont Index |

1.8+/− 1.75 | 2.4+/− 2.0 | 0.01 |

| Any urinary incontinence (ISI>0) | 45.6% | 45.0% | 1.0 |

| Incontinence Severity Index among those with any urinary incontinence on ISI |

1.7+/− 1.0 | 1.8+/− 1.3 | 0.80 |

| Sexual Function and Perineal Pain | |||

| Sexual variables on Female Sexual | |||

| Function Index | |||

| Sexually active | 87.9% | 90.2% | 0.83 |

| Female Sexual Function Index scores | 29.1+/−5.1 | 27.1+/−6.0 | 0.04 |

|

Individual Responses on Female Sexual

Function Index | |||

| Desire | 3.9+/11.26 | 3.6+/1.20 | 0.07 |

| Arousal | 4.3+/−1.79 | 3.7+/−1.77 | 0.03 |

| Lubrication | 4.6+/1.9 | 4.2+/−2.1 | 0.21 |

| Orgasm | 4.3+/−1.9 | 4.0+/−2.1 | 0.32 |

| Satisfaction | 4.8+/−1.4 | 4.2+/−1.4 | <0.01 |

| Pain | 5.2+/−1.0 | 4.6+/−1.6 | 0.01 |

| Perineal Pain Now- Visual Analog Scale | 0.12+/−0.8 | 0.38+/−1.4 | 0.19 |

| Perineal Pain now none (PPI=0) | 93.8% | 84.5% | 0.03 |

| Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Muscle | |||

| Function | |||

| Mean total vaginal length (cm) | 7.4 | 7.0 | 0.13 |

| Perineal Body Length (cm) | 3.3+/−0.8 | 3.5+/−0.8 | 0.16 |

| Genital Hiatus at rest (cm) | 2.7+/−0.7 | 2.7+/−07 | 0.53 |

| Genital Hiatus with strain (cm) | 3.3+/−0.8 | 3.30+/−0.74 | 0.84 |

| Internal anal sphincter not intact on transperineal ultrasound (N=266) |

8.5% | 14.6% | 0.20 |

| External anal sphincter not intact on transperineal ultrasound (N=264) |

0.0% | 1.9% | 0.20 |

| Kegel strength (none/weak vs.mod/strong) | 44.3% | 61.0% | 0.03 |

| Rectal resting tone (none/weak vs. mod strong) |

4.6% | 9.8% | 0.25 |

| Rectal squeeze | 41.8% | 48.8% | 0.48 |

| Paper towel test (%wet) | 19.9% | 13.8% | 0.35 |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse Stage | 0.43 * | ||

| 0 | 14.4% | 11.9% | |

| 1 | 66.2% | 65.4% | |

| 2 | 19.0% | 23.7% | |

| 3 | 0.4% | 0.0% | |

| Pelvic Floor impact Scores among all women |

2.2+/−9.4 | 2.0+/−5.5 | 0.83 |

| Pelvic Floor impact score among women with Stage 2 or greater pelvic organ prolapse |

4.6+/−14.0 | 2.0+/−4.5 | 0.31 |

ISI: Incontinence Severity Index; PPI: Present pain Intensity.

Jonckheere-Terpstra test

Acknowledgments

Funding: The project was Supported by NICHD 1R01HD049819-01A2 and National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8UL1TR000041.

Footnotes

Special instructions - None

Contributor Information

Leeman Lawrence, Departments of Family and Community Medicine, and Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM..

Rogers Rebecca, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM.

Borders Noelle, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

Teaf Dusty, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM.

Qualls Clifford, Clinical and Translational Research Center, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

References

- 1.Tahtinen RM, Cartwright R, Tsui JF, et al. Long-term Impact of Mode of Delivery on Stress Urinary Incontinence and Urgency Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European urology. 2016 Jul;70(1):148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trutnovsky G, Kamisan Atan I, Martin A, Dietz HP. Delivery mode and pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective observational study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2016 Aug;123(9):1551–1556. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leijonhufvud A, Lundholm C, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Andolf E, Altman D. Risks of stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse surgery in relation to mode of childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jan;204(1):70 e71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handa VL, Knoepp LR, Hoskey KA, McDermott KC, Munoz A. Pelvic floor disorders 5-10 years afters vaginal or cesarean childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Oct;118(4):777–784. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182267f2f. BJ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Souza A, Dwyer PL, Charity M, Thomas E, Ferreira CH, Schierlitz L. The effects of mode delivery on postpartum sexual function: a prospective study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2015 Sep;122(10):1410–1418. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leeman LM, Rogers RG. Sex after childbirth: postpartum sexual function. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119(3):647–655. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182479611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Postpartum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: a retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Apr;184(5):881–888. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.113855. discussion 888-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Dec;189(6):1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.030. discussion 1549-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bols EM, Hendriks EJ, Berghmans BC, Baeten CG, Nijhuis JG, de Bie RA. A systematic review of etiological factors for postpartum fecal incontinence. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2010 Mar;89(3):302–314. doi: 10.3109/00016340903576004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evers EC, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Handa VL. Obstetrical anal sphincter laceration and anal incontinence 5-10 years after childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;207(5):425 e421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albers LL, Sedler KD, Bedrick EJ, Teaf D, Peralta P. Midwifery care measures in the second stage of labor and reduction of genital tract trauma at birth: a randomized trial. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2005 Sep-Oct;50(5):365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannessen HH, Wibe A, Stordahl A, Sandvik L, Backe B, Morkved S. Prevalence and predictors of anal incontinence during pregnancy and 1 year after delivery: a prospective cohort study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2014 Feb;121(3):269–279. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers RG, Leeman LM, Migliaccio L, Albers LL. Does the severity of spontaneous genital tract trauma affect postpartum pelvic floor function? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008 Mar;19(3):429–435. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers RG, Leeman LM, Borders N, et al. Contribution of the second stage of labour to pelvic floor dysfunction: a prospective cohort comparison of nulliparous women. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2014 Aug;121(9):1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12571. discussion 1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meriwether KV, Hall RJ, Leeman LM, Migliaccio L, Qualls C, Rogers RG. Postpartum translabial 2D and 3D ultrasound measurements of the anal sphincter complex in primiparous women delivering by vaginal birth versus Cesarean delivery. International urogynecology journal. 2014 Mar;25(3):329–336. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jul;175(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampselle CM, Wells TJ. Digital measurement of pelvic muscle strength in childbearing women. Nurs Res. 1989 May-Jun;38(3):134–138. BC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller JM, Delancey JC. Quantification of cough-related urine loss using paper towel test. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;91(5):705–709. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00045-3. A-MJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley CS1, Morgan MA, Berlin M, Novi JM, Shea JA, Arya LA. A new questionnaire for urinary incontinence diagnosis in women: development and testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jan;192(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.037. RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanley J1, Hagen S. Validity study of the severity index, a simple measure of urinary incontinence in women. BMJ. 2001 May 5;322:1096–1097. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1096. CA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barber MD1, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul;193(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025. WM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Dec;185(6):1388–1395. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.118659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993 Jan;36(1):77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987 Aug;30(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen R1, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D'Agostino R., Jr. The female sexual function index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000 Apr-Jun;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CM M. Validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with female orgasmic disorder and in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003 Jan-Feb;29(1):39–46. doi: 10.1080/713847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leeman L, Fullilove AM, Borders N, Manocchio R, Albers LL, Rogers RG. Postpartum perineal pain in a low episiotomy setting: association with severity of genital trauma, labor care, and birth variables. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.) 2009 Dec;36(4):283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albers LL. Minimizing genital tract trauma and related pain following spontaneous vaginal birth. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2007 May-Jun;52(3):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.12.008. BN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nager CW, Helliwell JP. Episiotomy increases perineal laceration length in primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Aug;185(2):444–450. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Oct 15;68(8):1585–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macarthur AJ, Macarthur C. Incidence, severity, and determinants of perineal pain after vaginal delivery: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Oct;191(4):1199–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckmann MM, Stock OM. Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;4:CD005123. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005123.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dzakpasu S, Fahey J, Kirby RS, et al. Contribution of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain to caesarean birth in Canada. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, Caughey AB. Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2011 Jan;24(1):65–72. doi: 10.3109/14767051003710276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin JA, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Division of Vital Statisctics. Births: Final Data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013:62. HB. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankman EA, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Episiotomy in the United States: has anything changed? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;200(5):573. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.022. WL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JA, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Kiremeyer S, Mathews TJ, Wilson EC. Births: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011 Nov;60(1):1–70. HB. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia V, Rogers RG, Kim SS, Hall RJ, Kammerer-Doak DN. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter laceration: a randomized trial of two surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;192(5):1697–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vathanan V, Ashokkumar O, McAree T. Obstetric anal sphincter injury risk reduction: a retrospective observational analysis. Journal of perinatal medicine. 2014 Nov 1;42(6):761–767. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cam C, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Aran T, Tug N, Karateke A. Does mediolateral episiotomy decrease central defects of the anterior vaginal wall? Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2012 Feb;285(2):411–415. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1965-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]