Synopsis

Dry eye and dry mouth symptoms are each reported by up to 30% of persons over the age of 65 years, particularly in women. Multiple factors contribute to these symptoms, but medication side effects are the most common. The evaluation of these symptoms requires measures of ocular and oral dryness, some of which can be done by the geriatrician in a clinic setting. Sjögren syndrome is the prototypic disease associated with dryness of the eyes and mouth and predominantly affects women in their peri- and postmenopausal years of life. The diagnosis requires substantive evidence of autoimmune-induced inflammation targeting the salivary or lacrimal glands. With current classification criteria, the diagnosis can only be established if the patient has antibodies to the SSA (Ro) and/or SSB (La) antigens or a labial gland biopsy showing a characteristic pattern and severity of inflammation, in concert with at least one measure of ocular or oral dryness. A diagnosis is important, since this disease is associated with a substantial increased risk of lymphoma and other forms of morbidity. In addition to topical treatment of the mucosal dryness, patients with Sjögren's syndrome may require treatment with systemic immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents to manage a variety of “extraglandular” manifestations.

Keywords: Sjögren's syndrome, dry eye, aging, salivary hypofunction, xerostomia

Introduction

Symptoms of dryness of the eyes, mouth, and vagina (in women) are common among the elderly and have a substantial impact on life quality. The prevalence of these symptoms increases with age and reaches up to 30% in persons over the age of 65 years, particularly in women [1-5]. Objective evidence of diminished tear or saliva production is much less frequent [4-6], indicative of the weak association between dryness symptoms and objective measures. There are many potential causes for mucosal dryness in the elderly, and multiple factors can contribute in a single individual.

Sjögren syndrome (SS) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease characterized by dry eyes and dry mouth, arising from autoimmune-induced inflammation of the lacrimal and salivary glands. It primarily affects peri- and postmenopausal women and is a prime diagnostic consideration in an older patient with mucosal dryness. It can occur in a primary form or in association with another systemic autoimmune disease (labeled secondary SS). The reported prevalence of primary SS in population-based studies ranges from 0.01-0.09% [7]. SS is present in up to 17% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis [8, 9], a disease whose prevalence reaches 1.1% in the United States [10]. Thus, the overall prevalence is higher, making SS the second most common systemic rheumatic disease.

In this chapter, the authors will review the clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis, and medical evaluation of the elderly patient with dry eyes and mouth, as well as the approach to the diagnosis and management of SS.

Dry eye

Dry eye manifests most often with ocular irritation, including burning, stinging, soreness, and a foreign body sensation. The symptoms are aggravated by exposure to low humidity, wind or air drafts, as well as prolonged visual attention, including reading. Less frequent symptoms include blurred vision, excess tearing and blepharospasm.

Dry eye is generally caused by diminished tear production or by excessive tear evaporation [11] (Box 1). The former is most often due to lacrimal gland disease but can result from lacrimal gland duct obstruction or reflex hyposecretion related to corneal sensory loss. Excessive evaporation from meibomian gland dysfunction and other forms of blepharitis is more common. Other causes of dryness include incomplete lid closure during sleep, allergic conjunctivitis, and trachoma.

Box 1. Common causes of dry eye in the elderly.

| Aqueous tear deficiency | Evaporative tear deficiency |

|---|---|

| • Sjögren syndrome | • Meibomian gland dysfunction (posterior blepharitis) |

| • Age-related dry eye | • Exophthalmos, poor lid apposition, lid deformity |

| • Systemic medications (e.g. antihistamines, beta blockers, antispasmodics, diuretics) | • Low blink rate |

| • Lacrimal gland duct obstruction (e.g cicatricial pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid, trachoma, erythema multiforme, burns) | • Ocular surface disorders (e.g. vitamin A deficiency, toxicity from topical drugs/preservatives, contact lens wear) |

| • Ocular sensory loss leading to reflex hyposecretion (e.g. diabetes mellitus, corneal surgery, contact lens wear, trigeminal nerve injury) | • Ocular surface disease (e.g. allergic conjunctivitis) |

| • Lacrimal gland infiltration (e.g. sarcoid, lymphoma, graft vs host disease, AIDS, IgG4-related disease) |

Tear production and lipid content have been shown to diminish with age [12, 13] as a result of changes in lacrimal and meibomian glands, a decreased density of conjunctival goblet cells, and somatosensory nerve impairments [14]. In addition, the elderly frequently have conditions contributing to dry eye, such as use of medications with anti-cholinergic side effects, past refractive or cataract surgery [15], lagophthalmos, blink abnormalities, and conjunctivochalasis [16].

The assessment of dry eye requires multiple tests (Box 2). The Schirmer test measures tear production [17] and can be reliably performed by a geriatrician in a clinic setting. A sterile rectangular strip of filter paper, rounded and notched at the proximal end, is folded over the lower eyelid at the midpoint between the middle and lateral fornix of each eye. The patient is then asked to close the eyes gently during the 5 minute duration of the test. The extent of tear “wicking” or wetting is recorded in millimeters and is normally greater than 5 mm in both eyes. The Schirmer test can be performed with or without anesthesia to measure basal and reflex tear secretion, respectively. This test is imperfect in the elderly, since the results decline with age. In two population-based surveys of elderly individuals (65 years or older), the prevalence of an abnormal Schirmer test ranged from 12-58% [2, 4].

Box 2. Tests used to assess dry eye disease.

| Test | Abnormal value | Significance of abnormal test |

|---|---|---|

| Schirmer | < 5 mm/5 minute in either eye | Inadequate tear production |

| Ocular surface staining | Score ≥4 (van Bijsterveld) [18] Score ≥3 (SICCA) [19] | Damage to the ocular surface |

| Tear break up time | <10 seconds | Poor tear film stability, as seen in meibomian gland dysfunction |

| Tear osmolarity | ≥308 mOsm/L in either eye | Excessive tear evaporation, lacrimal gland disease, or ocular surface inflammation |

Data from van Bijsterveld OP. Diagnostic tests in the Sicca syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1969;82(1):10-4; and Whitcher JP, Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC et al. A simplified quantitative method for assessing keratoconjunctivitis sicca from the Sjögren's Syndrome International Registry. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149(3):405-15.

Ocular surface staining with vital dyes allows slit lamp visualization of devitalized conjunctival cells and corneal epithelial defects. Lissamine green is most commonly used to stain the conjunctiva and fluorescein the cornea. The extent of ocular surface staining is a measure of dryness-induced ocular surface damage, is one of the classification criteria for SS, and can be scored using methods described by van Bijsterveld and by the Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA) [18-20].

The tear break up time is used to assess the stability of the tear film [21] and is typically abnormal in meibomian gland dysfunction. Tear osmolarity measurement [22, 23] is the best for predicting dry eye severity [23].

Xerostomia and salivary hypofunction

Symptoms of dry mouth, termed xerostomia, include burning, dry lips, alteration of taste, and a sense of having an inadequate amount of saliva. There also may be difficulty speaking, swallowing and wearing dentures. The need to sip water to swallow dry food is an important marker of reduced salivary function [24]. Halitosis, painful tongue fissures, mucosal ulcers, and pain with ingestion of spicy or acidic foods are common discomforts that may stem from candidal overgrowth on the oral mucosa. The relation between salivation and xerostomia is complex. Dawes showed that healthy subjects report dry mouth symptoms when their baseline salivary flow is reduced by 50%, even if the residual salivary flow level remains within the broad range of normal [25].

Saliva is produced by the major (parotid, submandibular, sublingual) and myriad submucosal minor salivary glands. The parotid glands only produce saliva upon gustatory or olfactory stimulation. Saliva is continually secreted by the sublingual, submandibular, and minor salivary glands. This basal secretion is crucial for maintaining oral health.

Both unstimulated and stimulated salivary flow rates are measured. Saliva that pools in the mouth without stimulation can be collected for 5-15 minutes, providing a measure of “whole” saliva production in a clinic setting (Box 3). It is considered the most relevant measure of oral health. Stimulated whole salivary flow rates can be measured with the patient chewing gum or pre-weighed gauze and are not generally affected by medication use. With special research techniques, stimulated (e.g. with lemon juice on the tongue) and unstimulated saliva flow rates can be measured from the individual parotid glands or sublingual/submandibular glands.

Box 3. Measurement of unstimulated whole salivary flow rate.

| Unstimulated whole saliva collection measures saliva production under resting or basal conditions. The subject should not have had anything to eat or drink for 90 minutes before the procedure. The use of a parasympathomimetic should be discontinued for 12 hours before the procedure, and the use of artificial salivas should be stopped 3 hours prior. During the collection procedure, the subject is instructed to minimize actions that can stimulate saliva (talking, increased orofacial movement) and should not swallow. At time “0,” any saliva present in the mouth is cleared by swallowing. For the subsequent 5 minutes, any saliva collected in the mouth is emptied into a preweighed tube every minute (i.e., five times). This collecting tube then is weighed to determine a postcollection weight. The difference between the pre- and postcollection weight is determined, and this represents the unstimulated whole saliva production for 5 minutes. To convert to a volume of saliva from the weight of saliva, an assumption is made that saliva is similar to water, where 1 g of water/saliva at 4°C equals 1 mL of saliva/water. |

| Less than 0.100 mL/min is considered a reduced unstimulated salivary flow rate. |

From Wu AJ. Optimizing dry mouth treatment for individuals with Sjögren's syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008 Nov;34(4):1001-10; with permission.

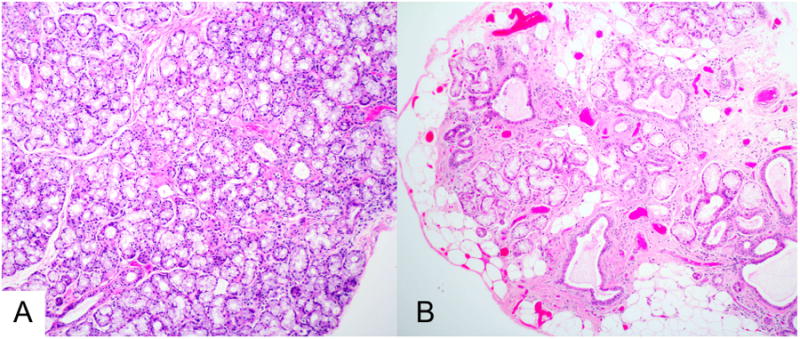

Human salivary glands undergo atrophy with age (Figure 1). In morphometric studies, aging was associated with acinar loss and replacement with fat and connective tissue [26, 27]. Whole unstimulated saliva flow rates decline with age, which may contribute to the age-dependent increase in dental caries [28]. However, this is not true for stimulated parotid saliva flow rates [29].

Figure 1.

Histopathology of minor labial salivary glands. The sections are from biopsies of a 28 year-old woman (panel A) and a 65 year-old woman (panel B), shown at the same magnification. The histopathologic section in panel A shows normal tissue, with confluent mucous acini and normal-sized intralobular ducts. In contrast, the section in panel B shows extensive acinar loss, interstitial fibrosis, ductal dilatation, and fatty replacement. The changes in panel B are often seen to varying degree in older patients. (Magnification 100 ×)

There are multiple potential etiologies for xerostomia and salivary hypofunction in the elderly (Box 4) [6]. Side effects from medications commonly used in the geriatric population are the most common.

Box 4. Common causes of dry mouth in the elderly.

|

Vaginal dryness

Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia and vulvar pruritus are common symptoms among post-menopausal women. These symptoms relate to menopause-related decreases in estrogen and other sex steroids but can also have other etiologies. In 2014, two international societies recommended that the range of symptoms and signs associated with menopause be termed the “genitourinary syndrome of menopause” [30]. These symptoms include genital dryness, burning, irritation, inadequate lubrication, dyspareunia, urinary urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Similar symptoms are also seen with infectious vaginitis, irritant or allergic vulvitis or vaginitis, vulvovaginal dermatoses, hypertonic pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, and pudendal neuralgia [30].

In women affected by SS, vaginal dryness can be severe and impact sexual ability and pleasure [31]. There is scant information regarding the etiology of this dryness. One hypothesis is that the Skene and related glands of the vaginal introitus are affected in the same manner as exocrine glands found elsewhere [32]. There has been no histopathologic confirmation of this to date.

Sjögren syndrome

SS is the prototypic illness of dryness of the eyes and mouth. It is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands. This chronic inflammatory process gradually leads to glandular injury and related dysfunction over the course of years, eventually causing the cardinal symptoms of dry eyes and mouth. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is the term coined by Henrik Sjögren in 1933 to describe the dry eye component of this syndrome [33]. Key features are shown in Box 5.

Box 5. Key clinical features of Sjögren syndrome.

|

SS disease onset is uncommon after the age of 65 or 70 [40, 41]. Older patients with SS, when compared to younger ones, have a lower frequency of serologic abnormalities, such as anti-SSA, anti-SSB, rheumatoid factor and hyperglobulinemia [42]. Parotid enlargement, arthalgia, and Raynaud's phenomenon are also less common, while higher frequencies of lung involvement and anemia have been noted [41]. A distinct subset of older SS patients with anti-centromere antibodies is characterized by Raynaud's phenomenon, overlap features of limited systemic sclerosis, and more severe salivary and lacrimal gland dysfunction [43].

The clinical presentation of SS is varied, but is most often that of mucosal dryness (Box 6).

Box 6. Modes of presentation of Sjögren syndrome.

|

SS is associated with a variety of systemic manifestations (Box 7). Some are direct manifestations of the disease while others represent coincidental autoimmune diseases. Apart from symptoms of fatigue, joint pain, and mild cognitive impairment (often labeled “brain fog”), the prevalence of these organ-specific manifestations is each less than 20% [44].

Box 7. Systemic manifestations of Sjögren's syndrome.

| Organ-involvement | Manifestation |

| Constitutional | Fatigue |

| Mild cognitive disturbance | |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthritis/arthralgia |

| Myositis (especially inclusion body myositis) | |

| Cutaneous | Annular erythema |

| Xerosis | |

| Palpable purpura | |

| Pulmonary | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| Follicular bronchiolitis | |

| Vascular | Raynaud's |

| Vasculitis | |

| Gastrointestinal | Atrophic gastritis |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | |

| Endocrine | Autoimmune thyroid disease |

| Cardiac | Pericarditis |

| Renal | Interstitial nephritis with renal tubular acidosis |

| Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | |

| Hematologic | Leucopenia, neutropenia |

| Thrombocytopenia | |

| Anemia | |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | |

| Cryoglobulinemia | |

| Lymphoproliferative | Lymphoma |

| Neurologic | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Ataxic ganglionopathy | |

| Myelitis (including neuromyelitis optica) |

The natural history is generally one of stability, with a slow decline in lacrimal and salivary gland function. It is not characterized by the types of disease flares seen in systemic lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, but patients may report periods of worsening sicca or fatigue. There is no increase in overall mortality according to a recent meta-analysis, but patients with specific extra-glandular manifestations, including those with vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, pulmonary disease and lymphoma, have been identified as having higher mortality rates [45, 46].

Diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome

The diagnosis requires evidence of autoimmune-induced inflammation targeting the salivary or lacrimal glands. Two sets of classification criteria are currently in use, the 2002 American-European Criteria Group (Box 8) and the 2012 American College of Rheumatology provisional classification criteria (Box 9) [47, 48]. Both require that the patient have either anti-SSA and/or anti-SSB antibodies or a minor salivary gland biopsy demonstrating focal lymphocytic sialadenitis with a focus score ≥1. These two sets of criteria have good concordance [49]. However, both criteria sets have limitations, and thus a new set of international consensus criteria is in development. We utilize these current classification criteria as a general guide, and establish the diagnosis if a patient has an objective measure of ocular and/or oral dryness or characteristic imaging abnormalities (e.g. by ultrasound, MR or CT), coupled with anti-SSA antibodies or a positive lip biopsy.

Box 8. American-European Consensus Group Revised International Classification Criteria for Sjögren's Syndrome.

|

|

|

| For primary SS |

In patients without any potentially associated disease, primary SS may be defined as follows:

|

| For secondary SS |

| In patients with a potentially associated disease (for instance, another well-defined connective tissue disease), the presence of item I or item II plus any 2 from among items III, IV, and V may be considered as indicative of secondary SS |

| Exclusion criteria: Past head and neck radiation treatment; hepatitis C infection; acquired immunodeficiency disease (AIDS); pre-existing lymphoma; sarcoidosis; graft versus host disease; use of anticholinergic drugs (since a time shorter than 4-fold the half-life of the drug) |

From Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61(6):554-8; with permission.

Box 9. American College of Rheumatology Provisional Criteria for Classification of Sjögren's Syndrome.

The classification of SS, which applies to individuals with signs/symptoms that may be suggestive of SS, will be met in patients who have at least 2 of the following 3 objective features:

|

Prior diagnosis of any of the following conditions would exclude participation in SS studies or therapeutic trials because of overlapping clinical features or interference with criteria tests:

|

From Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell L et al. American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(4):475-87; with permission.

For the practicing geriatrician, we recommend that a patient suspected of having SS be evaluated as follows:

History, seeking a history of persistent symptoms of dry eyes and/or mouth. Validated screening questions are included in the American European Classification Criteria (Box 8)

- Examination, seeking signs of salivary hypofunction and of a systemic rheumatic disease

- Oral examination

- Is there enlargement of the lacrimal or major salivary glands? What is the texture of the major salivary glands? Are there discrete nodules or masses?

- Does saliva pool under the elevated tongue when observed over the course of one minute?

- Does the tongue have deep fissures, a hyperlobulated appearance, or absence of filiform papillae on its surface?

- General examination

- Look for sclerodactyly, palpable purpura, synovitis, basilar pulmonary rales

- Laboratory testing

- Screen for ANA (tested by immunofluorescence assay), anti-SSA (Ro), and anti-SSB (La), and rheumatoid factor. Anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies can be present despite a negative ANA test.

- A CBC, urinalysis, and chemistry profile may reveal abnormalities supportive of SS, including leucopenia and neutropenia, hyperglobulinemia, renal impairment, and proteinuria.

- Ophthalmologic examination

- Schirmer testing is an appropriate initial test. A formal ophthalmologic examination will serve not only to confirm the diagnosis of dry eye but also define the contributing causes, such as meibomian gland dysfunction, conjunctivochalasis, etc. Guidelines for this evaluation can be found at https://sicca-online.ucsf.edu/documents/eye-exam-SOP.pdf

- Sialometry.

- Documentation of salivary hypofunction is only necessary if the eye examination does not show dry eye disease (Box 3).

- Labial gland biopsy

- A labial gland biopsy, best performed by an oral surgeon, is required for diagnosis if the patient lacks anti-SSA and/or anti-SSB antibodies. The biopsy also has value in excluding alternative diagnoses (such as sarcoid, amyloid, MALT lymphoma and IgG4-related disease). Guidelines for its performance can be found at https://sicca-online.ucsf.edu/documents/Oral-Saliva-SOP.pdf.

- Imaging (Figure 2)

- Salivary gland ultrasonography is favored due to its lower cost and lack of ionizing radiation. The presence of multiple ovoid hypoechoic lesions, often bounded by hyperechoic bands, correlates with markers of more severe disease. These imaging abnormalities have high specificity for the diagnosis, but only moderate sensitivity [50-54].

- CT imaging is not recommended because of the radiation exposure. However, the presence of multiple punctate calcifications within the parotid glands has high specificity [55].

- MR imaging of the parotid glands may reveal heterogeneity of signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images, with both hypointense and hyperintense foci measuring 1-4 mm in diameter [56].

Figure 2.

Imaging techniques in Sjögren's syndrome. This patient has bilateral symmetric parotid gland enlargement, seen best on the T2 fat-suppressed magnetic resonance images (panel A). Note the multiple T2-hyperintense foci scattered throughout both glands, a characteristic finding. With ultrasonography (panel B), multiple hypoechoic rounded lesions with convex borders are noted throughout the glandular parenchyma. In normal parotid gland tissue, the parenchyma has a homogeneous appearance with ultrasonography.

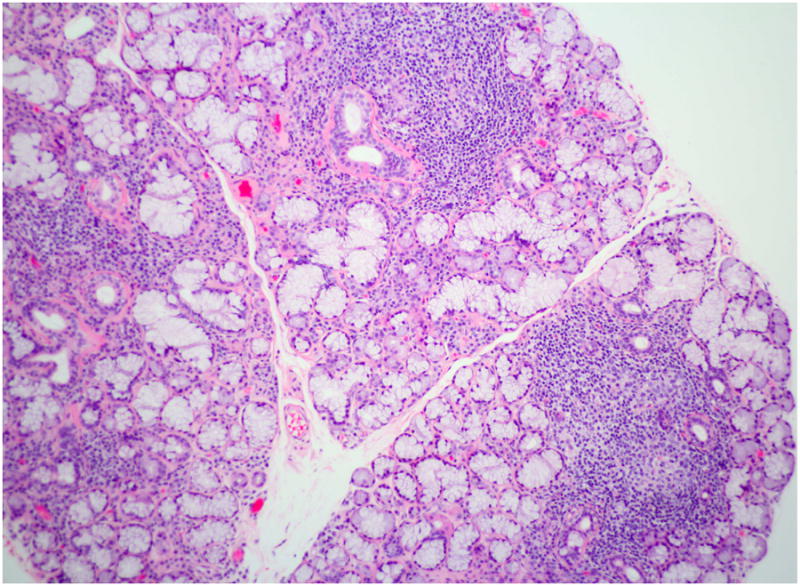

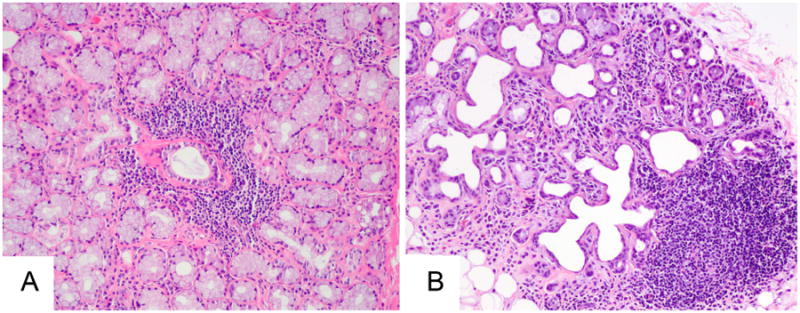

Be aware of certain common pitfalls in the diagnostic evaluation. Antibodies to SSA and SSB are not specific. They are frequently found in systemic lupus and inflammatory myopathies and are seen in up to 0.9% of healthy women in the US population [57]. Labial gland biopsies of older adults are also subject to misinterpretation. The histopathology of the minor salivary gland, termed “focal lymphocytic sialadenitis”, is characterized by lymphocytic aggregates which surround intralobular salivary ducts (Figure 3) and are adjacent to normal-appearing mucous-secreting acini. The number of these lymphocytic aggregates per 4 mm2 of glandular tissue section equates to the “focus score”. A score ≥1 is a criterion for the classification of SS and has been validated as the best cut-off value differentiating SS from non-SS controls [58]. Since chronic inflammation of the salivary gland can also arise from ductal obstruction and other forms of glandular injury, care must be taken to exclude from the focus score lymphocytic aggregates in areas of severe acinar loss, ductal dilatation, and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Focal lymphocytic sialadenitis. This section of a labial minor salivary gland biopsy shows the typical features of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis. Note the tightly aggregated lymphocytes surrounding ducts and adjacent to normal-appearing mucous acini. At least three foci are evident in this photomicrograph. (Magnification 100×).

Figure 4.

Potential misinterpretation of labial gland biopsies. The lymphocytic focus in the panel A is typical of that seen in focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, being centered around a duct and adjacent to normal-appearing mucous-secreting acini. In contrast, the lymphocytic focus in panel B is present within a gland lobule marked by interstitial fibrosis, ductal dilatation, and marked acinar loss. This focus should not be interpreted as representative of Sjögren's syndrome, (Magnification 100×).

In the elderly patient, the differential diagnosis of SS primarily includes alternative causes of sicca symptoms, salivary and/or lacrimal gland enlargement, and the characteristic serologic abnormalities.

Sicca complex in the elderly. Age-related interstitial fibrosis, acinar atrophy and nonspecific chronic inflammation in the labial gland biopsy may be misinterpreted as indicative of SS (Figure 4).

Salivary and/or lacrimal gland enlargement. In the elderly patient, particular attention should be paid to the possibility of lymphoma. IgG-4 related disease is more common in elderly men. It may present as unilateral submandibular gland enlargement (Köttner tumor) or parotid and lacrimal gland enlargement. Other diagnostic possibilities include amyloid infiltration, sarcoidosis, HIV infection, bulimia, and hyperlipoproteinemia.

Serologic abnormalities. Antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor and monoclonal proteins, are more prevalent in the elderly population [57]. Thus, positive tests must be interpreted cautiously when they happen to coincide with symptoms or signs of oral or ocular dryness.

Management of Sjögren's syndrome

The majority of patients only require topical and systemic treatments directed at alleviating their ocular, oral, and vaginal dryness, preventing dental decay, and managing oral candidiasis. Patients with systemic manifestations, including those with joint pain, skin lesions, and internal organ involvement, may benefit from immunomodulatory treatments. All SS patients require monitoring for disease complications, especially lymphoma.

Management of ocular dryness depends on its severity and the patient's response to therapy [59]. Avoidance of wind and smoke and protective eyewear can be helpful for all patients. Artificial tears with a demulcent (such as methylcellulose, propylene glycol and glycerine) are a mainstay of treatment. Patients should use preservative-free drops if drops are instilled four or more times a day. Use of thicker ocular gels and ointments before bed can help with dryness that occurs during sleep. Supplementation of the diet with omega-3 essential fatty acids has been shown to be of benefit. Use of topical cyclosporine and steroid solutions can be useful in a variety of dry eye conditions but should be undertaken in consultation with an ophthalmologist. Punctal plugs to preserve tears are often used in moderate to severe dry eye. Patients with more severe dry eye disease may require the use of moisture chamber spectacles, autologous serum tears, contact lenses or scleral prostheses.

Prevention of oral dryness includes maintaining good hydration and avoiding medications that worsen dryness. Patients should be counseled to be more aware of factors that can aggravate dryness, such as low humidity environments and mouth breathing. Frequent sips of oral solutions can be helpful, with options ranging from water to artificial saliva. Sucking on sugar-free hard candies helps stimulate saliva flow. Oral hygiene and dental care are essential in preserving dentition in persons with pathological oral dryness.

Muscarinic agonists, such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, can substantially increase saliva and to a lesser extent tear flow. However, overall tolerance of these agents may be hampered by cholinergic side effects of excessive sweating, increased urinary frequency, flushing, chills, rhinitis, nausea, and diarrhea. Care must be taken when with these medications are prescribed to the elderly.

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, including olive and vitamin E oils are initial treatment options for vaginal dryness. Vitamin E capsules can be opened and the oil used in and around the vagina. A suppository containing hyaluronic acid, vitamin E, and vitamin A, used once daily for 14 days, then once every other day for the next two weeks, can be effective [60]. Obtaining these suppositories requires a compounding pharmacist. Topical estrogen cream may help if symptoms do not improve with these other measures.

Hydroxychloroquine is commonly used for the management of joint pain and/or fatigue. However, clinical trials with this drug have shown mixed results, with none showing major clinical improvements [61-63]. The effect of immunosuppressive therapies on the glandular manifestations has been disappointing to date. The effect of rituximab on SS dryness is still being evaluated, with potential benefit being observed in a small double-blind placebo-controlled trial [64] but not in a larger one [65]. Prolonged therapy may be required for benefit [66].

Conclusion

Dryness of the eyes and mouth is a prevalent symptom among the elderly, most often related to the side effects of medications. However, there is a broad differential diagnosis for each symptom, and careful evaluation is important to define the etiology and correct treatment. SS is the prototypic disease that leads to these symptoms and primarily affects perimenopausal women. The diagnosis requires demonstration of an autoimmune disease underlying the sicca manifestations, either serologically or pathologically. Management can involve both topical and systemic therapies.

Key points.

Symptoms of dry eyes and dry mouth are common in the elderly and most often relate to medication side effects.

Sjögren syndrome is the prototypic illness that causes dry eyes and dry mouth and is an important diagnostic consideration in older individuals presenting with dry eye and mouth symptoms.

The diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome requires the presence of anti-SSA and/or anti-SSB antibodies, or a minor salivary gland biopsy demonstrating at least one tightly-aggregated periductal lymphocytic aggregate per 4 square millimeter of glandular tissue section (focal lymphocytic sialadenitis with a focus score ≥1).

Management of Sjögren syndrome requires attention to both the glandular (ocular and oral dryness, glandular enlargement) and extra-glandular manifestations (e.g. arthritis, pneumonitis, nephritis, vasculitis).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDCR

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johansson AK, Johansson A, Unell L, et al. Self-reported dry mouth in Swedish population samples aged 50, 65 and 75 years. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin PY, Tsai SY, Cheng CY, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1096–101. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billings RJ, Proskin HM, Moss ME. Xerostomia and associated factors in a community-dwelling adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(5):312–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schein OD, Munoz B, Tielsch JM, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(6):723–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay EM, Thomas E, Pal B, et al. Weak association between subjective symptoms or and objective testing for dry eyes and dry mouth: results from a population based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(1):20–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu B, Dion MR, Jurasic MM, et al. Xerostomia and salivary hypofunction in vulnerable elders: prevalence and etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin B, Wang J, Yang Z, et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(11):1983–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Jensen JL, et al. Sicca symptoms, saliva and tear production, and disease variables in 636 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58(7):415–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.7.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmona L, Gonzalez-Alvaro I, Balsa A, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: occurrence of extra-articular manifestations and estimates of disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(9):897–900. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.9.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1955-1985. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(3):415–20. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<415::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HENDERSON JW, PROUGH WA. Influence of age and sex on flow of tears. Arch Ophthal. 1950;43(2):224–31. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1950.00910010231004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathers WD, Lane JA, Zimmerman MB. Tear film changes associated with normal aging. Cornea. 1996;15(3):229–34. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gipson IK. Age-related changes and diseases of the ocular surface and cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(14):ORSF48–53. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasetsuwan N, Satitpitakul V, Changul T, et al. Incidence and pattern of dry eye after cataract surgery. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chhadva P, Alexander A, McClellan AL, et al. The impact of conjunctivochalasis on dry eye symptoms and signs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(5):2867–71. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho P, Yap M. Schirmer test. I. A review. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70(2):152–6. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Bijsterveld OP. Diagnostic tests in the Sicca syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82(1):10–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1969.00990020012003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitcher JP, Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, et al. A simplified quantitative method for assessing keratoconjunctivitis sicca from the Sjögren's Syndrome International Registry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):405–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bron AJ, Evans VE, Smith JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22(7):640–50. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sweeney DF, Millar TJ, Raju SR. Tear film stability: a review. Exp Eye Res. 2013;117:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemp MA, Bron AJ, Baudouin C, et al. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(5):792–798.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potvin R, Makari S, Rapuano CJ. Tear film osmolarity and dry eye disease: a review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2039–47. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S95242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115(4):581–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(87)54012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawes C. Physiological factors affecting salivary flow rate, oral sugar clearance, and the sensation of dry mouth in man. J Dent Res. 1987;66 Spec No:648–53. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott J, Flower EA, Burns J. A quantitative study of histological changes in the human parotid gland occurring with adult age. J Oral Pathol. 1987;16(10):505–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1987.tb00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syrjanen S. Age-related changes in structure of labial minor salivary glands. Age Ageing. 1984;13(3):159–65. doi: 10.1093/ageing/13.3.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Percival RS, Challacombe SJ, Marsh PD. Flow rates of resting whole and stimulated parotid saliva in relation to age and gender. J Dent Res. 1994;73(8):1416–20. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ship JA, Pillemer SR, Baum BJ. Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):535–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portman DJ, Gass ML Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddali Bongi S, Del Rosso A, Orlandi M, et al. Gynaecological symptoms and sexual disability in women with primary Sjögren's syndrome and sicca syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(5):683–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloch KJ, Buchanan WW, Wohl MJ, et al. Sjögren's Syndrome. a Clinical, Pathological, and Serological Study of Sixty-Two Cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1965;44:187–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjögren H. Zur Kenntnis der Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (Keratitis filiformis bei Hypofunktion der Tränendrüsen) Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1933;11(Suppl 2):1–151. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malladi AS, Sack KE, Shiboski SC, et al. Primary Sjögren's syndrome as a systemic disease: a study of participants enrolled in an international Sjögren's syndrome registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(6):911–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, et al. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):796–803. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin DF, Yan SM, Zhao Y, et al. Clinical and prognostic characteristics of 573 cases of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123(22):3252–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Perez-De-Lis M, et al. Sjögren syndrome or Sjögren disease? The histological and immunological bias caused by the 2002 criteria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010;38(2-3):178–85. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekstrom Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111(8):4029–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papageorgiou A, Ziogas DC, Mavragani CP, et al. Predicting the outcome of Sjögren's syndrome-associated non-hodgkin's lymphoma patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botsios C, Furlan A, Ostuni P, et al. Elderly onset of primary Sjögren's syndrome: clinical manifestations, serological features and oral/ocular diagnostic tests. Comparison with adult and young onset of the disease in a cohort of 336 Italian patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78(2):171–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramos-Casals M, Solans R, Rosas J, et al. Primary Sjögren syndrome in Spain: clinical and immunologic expression in 1010 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87(4):210–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318181e6af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haga HJ, Jonsson R. The influence of age on disease manifestations and serological characteristics in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28(4):227–32. doi: 10.1080/03009749950155599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baer AN, Medrano L, McAdams-DeMarco M, et al. Anti-centromere antibodies are associated with more severe exocrine glandular dysfunction in Sjögren's syndrome: Analysis of the Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 doi: 10.1002/acr.22859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brito-Zeron P, Ramos-Casals M EULAR-SS task force group. Advances in the understanding and treatment of systemic complications in Sjögren's syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(5):520–7. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh AG, Singh S, Matteson EL. Rate, risk factors and causes of mortality in patients with Sjögren's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55(3):450–60. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nannini C, Jebakumar AJ, Crowson CS, et al. Primary Sjögren's syndrome 1976-2005 and associated interstitial lung disease: a population-based study of incidence and mortality. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003569. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003569. 2013-003569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(6):554–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell L, et al. American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(4):475–87. doi: 10.1002/acr.21591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasmussen A, Ice JA, Li H, et al. Comparison of the American-European Consensus Group Sjögren's syndrome classification criteria to newly proposed American College of Rheumatology criteria in a large, carefully characterised sicca cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):31–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornec D, Jousse-Joulin S, Pers JO, et al. Contribution of salivary gland ultrasonography to the diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome: toward new diagnostic criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):216–25. doi: 10.1002/art.37698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takagi Y, Sumi M, Nakamura H, et al. Ultrasonography as an additional item in the American College of Rheumatology classification of Sjögren's syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(11):1977–83. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theander E, Mandl T. Primary Sjögren's syndrome: diagnostic and prognostic value of salivary gland ultrasonography using a simplified scoring system. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(7):1102–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.22264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldini C, Luciano N, Tarantini G, et al. Salivary gland ultrasonography: a highly specific tool for the early diagnosis of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:146. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0657-7. 015-0657-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luciano N, Baldini C, Tarantini G, et al. Ultrasonography of major salivary glands: a highly specific tool for distinguishing primary Sjögren's syndrome from undifferentiated connective tissue diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(12):2198–204. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun Z, Zhang Z, Fu K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of parotid CT for identifying Sjögren's syndrome. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(10):2702–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takashima S, Takeuchi N, Morimoto S, et al. MR imaging of Sjögren syndrome: correlation with sialography and pathology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15(3):393–400. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Satoh M, Chan EK, Ho LA, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of antinuclear antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2319–27. doi: 10.1002/art.34380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniels TE, Cox D, Shiboski CH, et al. Associations between salivary gland histopathologic diagnoses and phenotypic features of Sjögren's syndrome among 1,726 registry participants. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(7):2021–30. doi: 10.1002/art.30381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foulks GN, Forstot SL, Donshik PC, et al. Clinical guidelines for management of dry eye associated with Sjögren disease. Ocul Surf. 2015;13(2):118–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costantino D, Guaraldi C. Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: an open, non-controlled clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12(6):411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottenberg JE, Ravaud P, Puechal X, et al. Effects of hydroxychloroquine on symptomatic improvement in primary Sjögren syndrome: the JOQUER randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(3):249–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kruize AA, Hene RJ, Kallenberg CG, et al. Hydroxychloroquine treatment for primary Sjögren's syndrome: a two year double blind crossover trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52(5):360–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.5.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fox RI, Dixon R, Guarrasi V, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren's syndrome with hydroxychloroquine: a retrospective, open-label study. Lupus. 1996;5(Suppl 1):S31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Vissink A, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab treatment in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):960–8. doi: 10.1002/art.27314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):233–42. doi: 10.7326/M13-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carubbi F, Cipriani P, Marrelli A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in early primary Sjögren's syndrome: a prospective, multi-center, follow-up study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R172. doi: 10.1186/ar4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]