Abstract

Many open form (OF) structures of drug targets were obtained a posteriori by analysis of co-crystals with inhibitors. Therefore, obtaining the OF structure of a drug target a priori will accelerate development of potent inhibitors. In addition to its small active site, Trypanosoma cruzi dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (TcDHODH) is fully functional in its monomeric form, making drug design approaches targeting the active site and protein-protein interactions unrealistic. Therefore, a novel a priori approach was developed to determination the TcDHODH active site in OF. This approach consists of generating an "OF inducer" (predicted in silico) to bind the target and cause steric repulsion with flexible regions proximal to the active site that force it open. We provide the first proof-of-concept of this approach by predicting and crystallizing TcDHODH in complex with an OF inducer, thereby obtaining the OF a priori with its subsequent use in designing potent and selective inhibitors. Fourteen co-crystal structures of TcDHODH with the designed inhibitors are presented herein. This approach has potential to encourage drug design against diseases where the molecular targets are such difficult proteins possessing small AS volume. This approach can be extended to study open/close conformation of proteins in general, the identification of allosteric pockets and inhibitors for other drug targets where conventional drug design approaches are not applicable, as well as the effective exploitation of the increasing number of protein structures deposited in Protein Data Bank.

Introduction

Pyrimidine nucleotides are DNA and RNA building blocks derived from de novo biosynthesis and/or salvage pathways. In humans, both pathways are functional and disruption of one can result in compensation by the other[1]. However, rapidly proliferating cells, including cancer cells or activated lymphocytes, rely on de novo biosynthesis for their growth[2]. Therefore, drugs targeting de novo biosynthesis, N-(phosphonacetyl)- L-aspartate (PALA) and leflunomide (Arava®, Sanofi-Aventis), have anti-cancer and immunosuppressive activities[3],[2], respectively. PALA and A771726 (the active metabolite of leflunomide) inhibit the second (aspartate carbamoyltransferase) and fourth (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, DHODH) steps in de novo biosynthesis, respectively.

In many pathogens, such as Plasmodium falciparum and Helicobacter pylori, the enzymes required for the salvage pathway are missing from their genomes[4],[5], making them dependent on de novo biosynthesis. Among Trypanosomatid parasites, Trypanosoma cruzi, the pathogen of Chagas disease, is the only example which relies on pyrimidine de novo biosynthesis. Unlike T. brucei and Leishmania spp. (causative agents of human African trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis, respectively), the intracellular stage of T. cruzi lacks uracil phosphoribosyltransferase enzymatic activity[6]. Additionally, another key enzyme in the pyrimidine salvage pathway (uridine kinase) is missing from the T. cruzi genome[7]. Consequently, pyrimidine de novo biosynthesis is not essential for T. brucei [8],[9],[10] and L. donovani[11] growth, while T. cruzi strictly depends on it[12],[13]. Therefore, de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is an attractive target for the development of new drugs to combat Chagas disease.

Among the six steps required for de novo biosynthesis, the fourth step is catalyzed by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) and is a promising drug target because of its diversity. DHODHs are classified into two families according to cellular localization and electron acceptor. Family 1 DHODHs are cytosolic enzymes found in gram-positive bacteria, archaea, and lower eukaryotes. They are further subdivided into family 1A, a homodimeric FMN-containing enzyme using fumarate as an electron acceptor, and family 1B, a heterotetrameric enzyme containing FMN, FAD, and [2Fe-2S] cluster and using NAD+ as an electron acceptor. Family 2 DHODHs are found in gram-negative bacteria and eukaryotes, and are localized in the plasma membrane (bacteria) or mitochondrial inner membrane (eukaryotes). They are monomeric/homodimeric enzymes containing FMN and utilize respiratory quinones as electron acceptors[14]. The fact that family 1A DHODH is not connected to the respiratory chain allows some organisms having this class of enzyme, such as Trypanosomatid parasites, being able to biosynthesize pyrimidine even in the hypoxic microenvironment[15]. T. cruzi DHODH (TcDHODH) belongs to family 1A and by using structures complexed with substrates and products, we previously showed that the enzyme utilizes the same site for the first-half (dihydroorotate oxidation) and second-half (fumarate reduction) reactions[16], while family 1B[17] and 2[18] utilize distinct sites for these reactions. However, there are no reports of a potent, specific inhibitors targeting family 1A DHODHs to date.

Respiratory chain (RC) enzymes are promising drug targets because of their wide diversity among species. For example, the RC of blood stream forms of T. brucei possesses trypanosome alternative oxidase (TAO), a membrane associated diiron protein that functions as the sole terminal oxidase, which is absent in human[19]. Potent inhibitor of TAO, ascofuranone (AF), has strong trypanocidal activity in vitro and in vivo[20],[21],[22]. Another example is an anaerobic RC of the helminthes. The RC of adult Ascaris suum and Echinococcus multilocularis protoscoleces, contain an anaerobic NADH-fumarate reductase (NADH-FRD) system composed of Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase)[23], low potential quinone species (rhodoquinone) and Complex II catalyzing the reverse reaction [quinol:fumarate reductase (QFR)[24],[25]]. Inhibitors of Complex I have been shown to kill E. multilocularis protoscoleces in vitro, thus chemically validating the NADH-FRD system as a drug target[25]. We have also discovered atpenin A5 as the most potent inhibitor of respiratory Complex II which was later found to inhibit not only eukaryotic but bacterial enzyme as well [26]. Previously, we reported the crystal structures of TAO in complex with ascofuranone derivatives (3VVA and 3W54)[27] as well as A. suum QFR in complex with flutolanil (3VR9 and 3VRB)[28],[29],[30], its derivatives (4YSZ, 4YT0, 4YTM, 4YSX and 4YSY) and the substrate rhodoquinone (5C2T)[31], providing structural insights into their inhibition mechanisms. Both type of inhibitors bind to the quinol binding site of each target. Because family 2 DHODHs directly link pyrimidine de novo biosynthesis to the RC, structure-based drug-design (SBDD) targeting the ubiquinone binding sites of human[32],[33],[34] and P. falciparum[35],[36],[37],[38] DHODHs have been extensively studied, and species-selective DHODH inhibitors were rationally designed. However, these inhibitors target the ubiquinone binding site of only family 2 enzymes and have no obvious effect on family 1A DHODHs since the later lacks the ubiquinone binding site. Because of differences in ubiquinone dependency between human and T. cruzi DHODHs, the main focus of this study was the design of potent and selective inhibitors targeting the family 1A enzyme TcDHODH.

The continuing discovery, in random screening studies, of potent inhibitors that bind and expand the volume (open form, OF) of the target molecule active site emphasizes the importance of the target protein OF structure in drug discovery[39]. However, all targetable OF structures reported to date were obtained a posteriori to the discovered inhibitors. Specifically, they were unexpectedly found binding to the OF after determination of target/inhibitor co-crystal structures. Thus, we hypothesized that obtaining the OF structure of a target protein a priori will enable the design of potent inhibitors using conventional approaches. However, the lack of tools and reports where the OF structure of a target protein was rationally obtained a priori have substantially delayed structure based drug design (SBDD) targeting TcDHODH.

In this study, the “OF inducer” approach was developed in order to obtain the OF structure of TcDHODH a priori. Here, the OF inducer was designed and co-crystallized with TcDHODH. As expected, the structure of TcDHODH with an OF active site was successfully determined. The OF structure was subsequently used to design and synthesize several potent and selective inhibitors. From the 13 orotate derivatives designed in this study, the co-crystal structures of TcDHODH in complex with all derivatives were obtained. This allowed us to validate the OF inducer approach as a novel and powerful tool to understand the OF structures and consequently enabling the design of potent and specific inhibitors.

Material and Methods

Enzyme assays

The enzyme activity of TcDHODH was assayed spectrophotometrically by monitoring the direct production of orotate at 290 nm. The TcDHODH standard assay (TSA) solution contained 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM fumarate, and 1 μg/ml of TcDHODH. Equal volumes (2 μl) of an inhibitor dilutions series (11 wells for inhibitor plus 1 for DMSO control) were transferred to a 96 well plate with UV transparent flat bottom (Corning Inc.) followed by 188 μl of TSA solution. To assess background activity, the plate was placed in a SpectraMax M2e-TUY plate reader (Molecular Devices), mixed for 5 seconds before the first read (kinetic mode) and 3 seconds between reads during the 5 minute assay. The reaction was started by quickly adding 10 μl of 10 mM L-dihydroorotate stock solution (final concentration of 500 μM) and TcDHODH activity was assayed with the same parameters used in the background assay. The rate (Abs/min) during the first 2 minutes was calculated using SoftMax Pro 5.3 software (Molecular Devices). The rate relative to DMSO control (100%) versus inhibitor concentration was plotted and IC50 values calculated as the concentration of inhibitor that produces a 50% reduction in relative enzymatic activity. For HsDHODH, the standard assay (HSA) mixture contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.05% (w/v) Triton X-100, 200 μM L-dihydroorotate, 120 μM 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP), and 14 μM decylubiquinone (dUQ). A reaction start (RS) solution was prepared, containing 40 μg/ml HsDHODH (specific activity of 50 μmol/min/mg) in 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% (w/v) Triton X-100. Ten microliter of inhibitor dilution series were transferred to a 96 well plate (Nunc) and mixed with 185 μl of HSA. The plate was vortexed for 20 seconds and the background recorded for 5 min at 600 nm. The reaction was started by adding 5 μl of RS solution, vortexing for 20 seconds, and HsDHODH activity assayed using the end point method after 20 minutes with a SpectraMax M2e-TUY plate reader (Molecular Devices) and analyzed using SoftMax Pro 5.3 software (Molecular Devices). The amount of DCIP reduced in the presence of DMSO was set to 100%, the relative activity versus inhibitor concentration was plotted and the IC50 values calculated. Each data point was assayed in triplicate on the same day. Kiapp values were calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff equation with a Km for dUQ of 14.0 μM and for dihydroorotate of 25.9 μM as previous described, for HsDHODH[33] and TcDHODH[15], respectively.

Size exclusion chromatography

The size of TcDHODH was estimated by HPLC using a TSK gel G3000SW (Tosoh) column (7.5 × 600 mm), as previously described[15],[16]. Purified TcDHODH (0.5 mg) was mixed with 50 μl of Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-Rad) and injected to the column. The analysis was performed at room temperature with a flow rate of 1 ml/min in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 500 mM NaCl and 0.25 mM sodium orotate. The molecular weight of TcDHODH was calculated as 37 kDa based on the retention times of proteins in the Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-Rad).

DHODH activity staining

Blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) of TcDHODH was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1250 to 20 ng of pure TcDHODH in 5% (v/v) glycerol and 0.01% (w/v) Ponceau S was loaded onto a 4–16% (w/v) Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V using the light blue cathode buffer method [0.002% (w/v) of G-250 blue dye] at 4°C. Electrophoresis was terminated when the Ponceau S band reached approximately 1 cm from the bottom of the gel. The gel was transferred to a container, washed three times with 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 and incubated with 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 containing 2.5 mg/ml nitro blue tetrazolium chloride. The TcDHODH band was stained with L-dihydroorotate (0.25 mM) without phenazine methosulfate (PMS) at room temperature. A dark purple band corresponding to TcDHODH appeared within 5 seconds in the lane containing 1250 ng and within 2 minutes in the lane containing 20 ng. Since HsDHODH is a membrane protein and requires Triton X-100, high-resolution clear native electrophoresis was chosen for DHODH activity staining. Purified HsDHODH (1250 to 50 ng) was loaded onto 4–16% (w/v) Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V at 4°C, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HsDHODH activity was stained as described for TcDHODH, however in the presence of 0.06 mg/ml PMS. After DHODH activity staining, the gels were extensively washed with water and the molecular weight marker (NativeMarkTM Unstained Protein Standard, BioRad) was stained with GelCode® Blue Stain Reagent (Pierce). The molecular weight of TcDHODH and HsDHODH was calculated by constructing a Ferguson plot[40] using the NativeMarkTM standards.

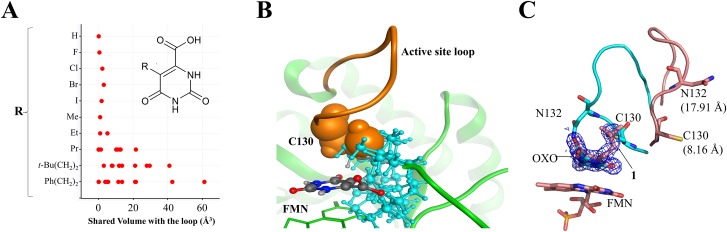

Assessment of steric repulsion between 5-substituted orotate and the active site loop moiety

To obtain a crystal structure with open loop conformation, steric repulsion between substituents (R-groups) at the 5-position of orotate and the active site loop (L128-Q138) of the closed form of TcDHODH were assessed. Firstly, nine orotate derivatives with different sized 5-substituents were prepared in silico. The conformational searches of the nine derivatives were performed using the modeling software MOE 2007.09[41], with MMFF94x force field, and stable conformers (ΔE ≤ 5 kcal/mol) for each compound were selected. The generated conformers were superposed with orotate on the closed form of TcDHODH. Using the superposed models, van der Waals volumes shared between a substituent at the 5-position of orotate and the active site loop was calculated for each conformer. Fig 1A shows the distribution of the calculated shared volumes of the orotate derivatives. To stably change the conformation of the loop, propyl, 3,3-dimethylbuthyl, and ethylbenzene groups were predicted to have sufficient sizes compared with those of halogen, methyl, and ethyl groups. Orotate derivative containing 3,3-dimethylbuthyl was selected as the first OF inducer and its binding mode confirmed by co-crystallographic study.

Fig 1. Generation of OF inducer.

(A) Shared volume between various conformers of the 5-substituent group (inset) and C130 from the active site loop. The graph was generated using coordinates from the TcDHODH-orotate complex structure (2E6A)[16] and calculated using MOE[41]. (B) Superposition of various conformations of 1 generated by MOE[41] to the active site of the TcDHODH-orotate complex structure. FMN and TcDHODH are shown in green as stick and ribbon, respectively. The active site loop and C130 are shown in orange. Different conformations of 1 are shown as ball-and-stick with carbon, nitrogen and oxygen colored in gray, blue, and red respectively. For better visualization, all atoms from the t-butyl-ethyl moiety are colored in cyan. (C) Superposition of the B chain from TcDHODH-1 (3W1Q, salmon) and -oxonate (2E6F, cyan)[16] complex structures. The electron density map, contoured at 1 σ, from 1 is shown. C130 and N132 residues are represented as stick. The distance moved relative to the respective positions from the TcDHODH-oxonate complex structure (2E6F)[16] for Sγ group (C130) and Nδ2 (N132) are shown in parenthesis.

Design of the 5-substituted orotate library based on the open form of TcDHODH

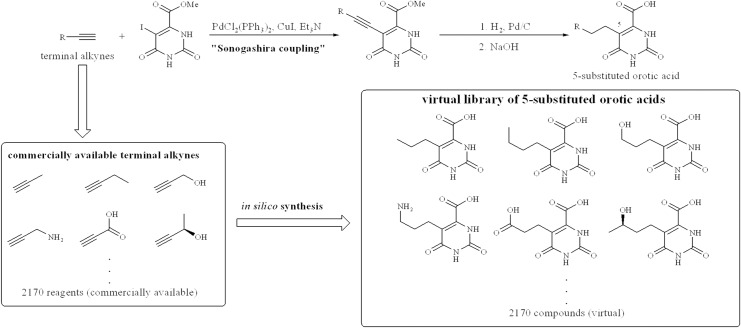

From the analysis of ligand contact preference around the orotate binding site according to the modeling software MOE[41], the binding region around the 5-position of orotate was predicted to preferably interact with hydrophobic ligand atoms. In fact, the region is surrounded by the hydrophobic amino acid residues L71, L101, and P131. Across the hydrophobic region, there are H-bonding sites, such as N53 and R50, which are accessible with substituents at the 5-position of orotate. To improve potency of orotate derivatives by interacting with the predicted pharmacophore features, we designed a 5-substituted orotate library. 5-Substituted orotate derivatives can be synthesized using a coupling reaction between 5-bromoorotate and tributylstannyl olefins. Tributylstannyl olefins can be prepared from terminal alkynes. The 2170 commercially available terminal alkynes listed in the ACD database (Molecular Design Limited, San Leandro, CA, USA) were used to construct a virtual 5-substituted orotate library. The terminal alkynes were transformed into their 5-substituted orotate forms using a customized protocol on Pipeline Pilot[42]. The 2170 virtual compounds were docked with the open form of TcDHODH using the docking program GLIDE[43]. The crystal structure of the TcDHODH-1 complex has two chains with different degrees of openness. Between the two chains, the more open form of TcDHODH was used for docking. From the docking results of the 2170 compounds, 225 compounds with new interaction(s) and good docking scores (GLIDE score ≤ -10.0 kcal/mol) were selected; the GLIDE score criteria (-10.0 kcal/mol) was determined according to the score distribution of known TcDHODH inhibitors such as orotate, oxonate, and succinate. The 225 compounds were clustered into three groups using interaction pattern analysis. Higher scoring compounds from each cluster (9 compounds in total) were identified and selected for synthesis.

Synthesis of 5-substituted orotate derivatives

Alkyne (1.5 mmol), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 mmol), CuI (0.2 mmol), and Et3N (2 mmol) were added to an iodide [CAS: 116393-71-6] (1 mmol) solution in THF (5 mL) at room temperature. After stirring overnight at room temperature, the mixture was diluted with hexane and filtered. The residue was washed with CH2Cl2 and dried in vacuo to afford crude alkyne, which was used in the next reaction without further purification.

Pd/C [(5% (w/w)] or Pd(OH)2/C [20% (w/w)] was added to a solution of the crude alkyne in MeOH/AcOH (9:1, 10 mL). After stirring under H2 atmosphere at room temperature for 12 h, the mixture was filtrated through a celite pad. The residue was washed with MeOH and dried in vacuo to afford crude methyl ester, which was used in the next reaction without further purification.

1 M NaOH aq (0.1 mL) was added to a suspension of the crude methyl ester in EtOH (1 mL) at room temperature. After stirring at 50°C for 6 h, the solvent was evaporated. The resulting solid was dissolved in monoethanolamine-AcOH (pH 9) buffer and purified with HPLC (monoethanolamine-AcOH (pH 9) buffer/CH3CN) to afford the orotic acid derivatives as monoethanolamine salts.

Crystallization

TcDHODH was expressed, purified, and crystallized essentially according to the methods described previously by Inaoka[44], [16]. Co-crystal structures of TcDHODH with 5-substituted orotate derivatives were prepared by initial soaking of TcDHODH-oxonate crystals in a fresh reservoir solution containing 0.05 mM 5-substituted orotate derivatives (soaking solution) and then gradually increasing its concentration every 12 hours, up to 0.2 ~ 5 mM.

Data collection

The TcDHODH crystal was briefly soaked in the reservoir solution with highest concentration of 5-substituted orotate derivatives containing 20% (v/v) glycerol and flash-frozen in a nitrogen stream at the beam line [Spring-8 (SP8) beam lines: BL44XU and BL41XU; Photon Factory (PF) beam lines: BL5A, BL17A, NE3A, or NW12A; see S1 Table]. All the data sets were processed and scaled with HKL2000[45].

Refinement

The crystal structure of TcDHODH in complex with compound 1 was solved by molecular replacement using the coordinates from TcDHODH-oxonate (2E6F)[16] as the search model. For the remaining co-crystal structures of TcDHODH in open form, the coordinates from TcDHODH-compound 1 (3W1Q) was used. Manual building of the remaining model from TcDHODH and further crystallographic refinement were performed with the COOT[46] and REFMAC5[47] softwares. Data collection and structural refinement statistics are summarized in S1 Table. Figures showing protein structures were prepared with the graphics programs PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/) and MOE[41].

Results and discussion

Open form inducer design

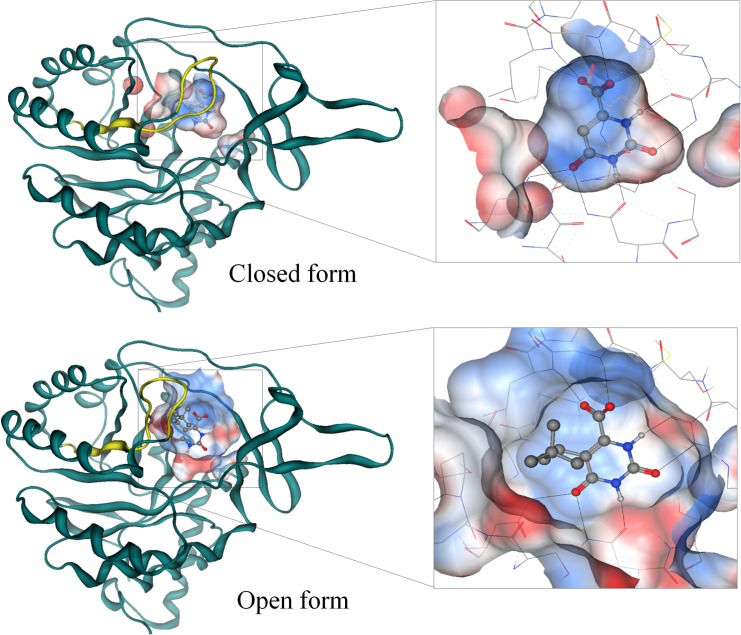

The small volume of the closed form of TcDHODH impedes the design of nanomolar inhibitors. Therefore, a new approach was developed to obtain the OF a priori for the purpose of designing potent inhibitors. In the ligand-free structure of TcDHODH, the electron density map of the active site loop (L128-D142) is poorly defined, indicating a high degree of flexibility[16], which is stabilized only by binding of ligands in the active site. We have previously reported that the Sγ atom of C130 in the active site loop, the key residue during catalysis, is located just 3.52 Å away from C5 of the dihydroorotate pyrimidine ring[16]. Because of the close contact with the active site loop, several orotate derivatives containing small substituents at C5 of the pyrimidine ring were analyzed in silico. The degree of steric repulsion with the flexible loop was calculated as the shared volume between C130 and various conformers of 5-substituents (Fig 1A). Of the 5-substituted derivatives analyzed, the t-butyl-ethyl and phenyl-ethyl groups were predicted to cause higher degrees of steric repulsion than halogen and short alkyl groups (Fig 1A). Fig 1B shows the calculated alternative conformers of 1, docked into the orotate binding site, causing steric repulsion with C130. To validate the OF inducer approach, 1 was synthesized and evaluated. Despite the low inhibitory activity of 1 (IC50 ≥ 400 μM, Table 1), the crystal structure of TcDHODH in complex with 1 was successfully prepared by soaking method. After refinement, a clear electron density map corresponding to 1 was readily distinguished from oxonate (Fig 1C). As expected, 1 was found binding with its t-butyl-ethyl group replacing the position occupied by Sγ of C130 in the closed form, forcing active site opening (Fig 1C). Previously, three regions around the active site loop were identified as potential drug-binding sites: the active site (S1), extension of S1 site (S2), and the site behind the active site loop (S3)[48]. The binding of 1 pushed the active site loop to the S2 site; in addition, the S1 and S3 sites become connected by the region previously occupied by the active site loop (S1 Fig). Binding also increased to more open in the active site of chain B than A due to crystallization packing. In chain B, Sγ of C130 moved 8.16 Å while Nδ of N132 moved 17.91 Å (Fig 1C). The drastic movement of the active site loop in chain B expanded the active site volume from 178 Å3 (closed form, Fig 2 top) to 694 Å3 (OF, Fig 2 bottom). The OF active site completely revealed the tunnel connecting the solvent to the active site. Binding also exposed the hydrophobic region and hydrogen bonding sites located across the binding site which are predicted to be accessible with 5-substitutions of the orotate pyrimidine ring (S2 Fig).

Table 1. 5-substituted orotate derivatives designed in this study.

| Inhibitor | 5-substituent | TcDHODH (μM) | HsDHODH (μM) | SI | Co-crystalb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Kiapp | IC50 | Kiapp | (Fold)a | Resolution (Å) | PDBc | ||

| OROd | H | 112 ± 21 | 5.51 | n.d.e | n.d. | n.d. | 1.64 | 2E6A |

| 1 | 2,2‐dimethylpentane | > 400 | > 19.7 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.85 | 3W1Q |

| 2 | propylbenzene | 62.4 ± 16.9 | 3.07 | > 5,000 | > 2,500 | > 814 | 1.58 | 3W1R |

| 3 | 1-propyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 0.62 | 284 ± 50 | 142 | 231 | 1.68 | 3W1T |

| 4 | 2-propylnaphthalene | 4.51 ± 0.09 | 0.22 | 46.1 ± 17.2 | 23.1 | 104 | 1.67 | 3W7H |

| 5 | 1-propylnaphthalene | 15.5 ± 0.8 | 0.76 | 434 ± 41 | 217 | 284 | 1.55 | 3W72 |

| 6 | 1-methoxy-6-propylnaphthalene | 2.24 ± 0.42 | 0.110 | 20.6 ± 3.1 | 10.3 | 93.6 | 1.75 | 3W7C |

| 7 | 2-methoxy-6-propylnaphthalene | 2.89 ± 0.07 | 0.14 | 46.2 ± 3.2 | 23.1 | 163 | 1.97 | 3W3O |

| 8 | 2-methoxy-7-propylnaphthalene | 5.90 ± 0.19 | 0.29 | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 6.65 | 22.8 | 1.82 | 4JDB |

| 9 | 6-propylnaphthalene-1-carboxylic acid | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.03 | > 5,000 | >2,500 | > 75,760 | 2.63 | 3W6Y |

| 10 | 6-propylnaphthalene-2-carboxylic acid | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.02 | 1,785 ± 1,773 | 893 | 37,210 | 1.58 | 3W7J |

| 11 | 1-methyl-4-propylbenzene | 8.68 ± 0.68 | 0.427 | 5.77 ± 0.66 | 2.88 | 6.75 | 1.85 | 3W1U |

| 12 | 1-tert-butyl-4-propylbenzene | 22.4 ± 2.1 | 1.10 | 16.8 ± 1.4 | 8.40 | 7.64 | 1.98 | 3W22 |

| 13 | 1-phenoxy-4-propylbenzene | 22.6 ± 1.5 | 1.11 | 16.6 ± 1.8 | 8.30 | 7.48 | 2.60 | 3W70 |

| 14 | 4-propyl-1,1'-biphenyl | 16.0 ± 1.9 | 0.79 | 0.97 ± 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 1.68 | 3W71 |

a, selectivity index calculated from the ratio of HsDHODH Kiapp / TcDHODH Kiapp values.

b, information from co-crystal structures of 5-substituents with TcDHODH.

c, Protein Data Bank identification code

d, orotate

Fig 2. The active site structure upon binding of OF inducer.

(Top) Ribbon representation of the TcDHODH structure in complex with orotate (ORO, PDB: 2E6A)[16]. (Bottom) Structure of the TcDHODH in complex with 1 (3W1Q). Yellow loop represents the active site loop (S128—V139). A “zoom in” pose of the active site pocket is shown (inset) with hydrogen bonds represented as dotted lines. Ball-and-stick represents ORO and atoms of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen colored in gray, blue, red, and white, respectively.

Design of potent and selective 5-substituted orotate derivatives

5-Substituted orotate derivatives can be easily synthesized from terminal alkynes (Fig 3). Using commercially available terminal alkynes, a virtual library containing 2170 orotate derivatives was constructed and docked into the OF TcDHODH (Fig 3). From the resulting 225 compounds with high docking scores, 4 compounds (2–5) with higher docking scores, predicted to interact with the hydrophobic region, were selected and synthesized (Table 1). To validate our predictions, the IC50 and Kiapp values of 2–5 were analyzed. All 4 compounds were more potent than orotate (Table 1). In order to determine the selectivity index (SI) of the orotate derivatives, recombinant human DHODH (HsDHODH) was purified and the IC50 and Kiapp values determined. 2 did not inhibit HsDHODH at high concentrations (5 mM) and exhibited higher SI (> 814-fold) than 3, 4, and 5 (231, 104, and 284, respectively; Table 1). To confirm the structural basis of predicted versus crystallographic inhibitor binding modes and selectivity, the structures of TcDHODH complexed with 2–5 were determined. The binding mode of each derivative was found to be consistent with our docking model (S3 Fig). In the crystal structures, the 5-substituent group of 2–5 (Table 1) interacts through CH-π interactions with P131 at the hydrophobic region, which explains their increased inhibitory potency compared to orotate (S3 Fig). The low Kiapp (0.22 μM) of 4 is the result of a unique interaction, in which the naphthyl group is sandwiched by CH-π interactions between G70 and P131, which are not observed with compounds 2, 3, and 5 (S3 Fig). The high selectivity of those compounds against TcDHODH is attributed to the L71 to F149 substitutions in HsDHODH. The bulkier side chain of F149, compared to L71, causes steric repulsion with the 5-substituted group, making binding to HsDHODH unfavorable. From these results we can conclude that the hydrophobic region can be targeted to increase the inhibitory potency as well as to increase the selectivity of these compounds toward TcDHODH.

Fig 3. Virtual library of 5-substituted orotate derivatives.

5-Substituted orotate derivatives can be synthesized by Sonogashira coupling using terminal alkynes. A virtual library was generated in silico using all 2170 commercially available terminal alkynes, screened against the more OF TcDHODH-1 crystal structure and clustered into groups according to their docking scores. 20 compounds with high docking scores were selected and synthesized.

The effect of an additional hydrogen bond in the 5-substituted orotate derivatives was also investigated by introducing methoxy groups at positions 5, 6, and 7 of the naphthyl ring (6, 7, and 8, respectively, Table 1). 6 and 7 decreased the by 2-fold (0.11 μM and 0.14 μM, respectively, Table 1), and Kiapp is slightly increased in 8 (0.29 μM), in comparison to 4 (0.22 μM). These changes in Kiapp values can be clearly explained by the co-crystal structures. According to our predictions, the methoxy groups on 6, 7, and 8 should form hydrogen bonds with the NH2 side chain of N53. In fact, a hydrogen bond between the methoxy group and N53 was observed in 7 bound to the A and B chains and in 8 bound to the A chain. However, an unexpected hydrophobic interaction between the methoxy group and the alkyl side chain of K214 was found in 6 (S4 Fig). This hydrophobic interaction was also seen in the A chain of the TcDHODH-7 co-crystal structure. The comparison of binding modes and Kiapp (Table 1) between 6 and 7 clearly indicates that the loss of the hydrogen bond with N53 can be compensated with an unusual hydrophobic interaction with the alkyl side chain of nearby K214 without affecting the Kiapp values. Since the CH-π interaction between P131 and the naphthyl group of 8 was lost (S4 Fig), this may contribute to the slightly higher Kiapp value of 8 compared to 6 and 7. These results indicate that optimum interaction with K214 and N53 can be achieved by introducing a hydrogen bond acceptor at positions 5 and 6 of the naphthyl group, respectively.

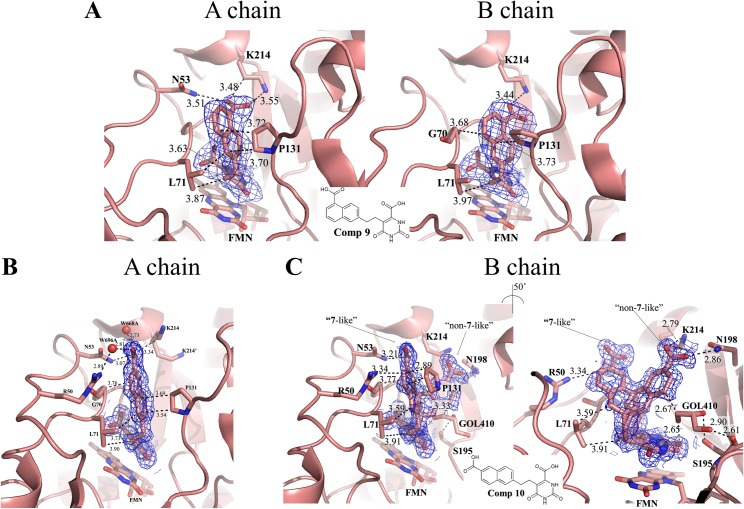

In order to strengthen the interaction with K214 and N53, carboxylate groups at positions 5 and 6 (9 and 10, respectively, Table 1) of the naphthyl group were introduced. Considering the pKa of 3.69 and 4.17 of 1- and 2-naphthoic acid, respectively[49], it is expected that the carboxylate groups in 9 and 10 should be present in anionic form during crystallographic studies (pH 5.3). Carboxylate group substitution remarkably decreased the Kiapp of 9 (0.03 μM) and 10 (0.02 μM). It also increased the Kiapp for HsDHODH to >2500 and 893 μM for 9 and 10, respectively (Table 1). Consequently, this dramatically increased the selectivity index against TcDHODH to >75800 and 37200 for 9 and 10, respectively (Table 1).

Since 9 and 10 are the most potent inhibitors of family 1A DHODHs reported, their co-crystal structures in complexes with TcDHODH were obtained and the binding mode was analyzed in detail. Fig 4A shows the binding mode of 9 in the A (left) and B (right) chains of TcDHODH. As expected, the carboxylate group of 9 formed a salt bridge with K214. With 10, the predicted hydrogen bond with N53 in chain A was confirmed by the co-crystal structure (Fig 4B). Interestingly, 10 was found binding in a dual mode in the B chain (Fig 4C); “7-like” and “non-7-like” binding modes perfectly fit into the density map (Fig 4C). In 7-like mode, the carboxylate group forms a hydrogen bond with N53 (Fig 4C, left) while in non-7-like mode it forms a salt bridge with K214 and a hydrogen bond with N198 (Fig 4C, right). The similarity of the B-factors of the non-7-like (9.2) and 7-like (10.2) binding modes of 10 and the protein [B-factors are 9.8 and 11.8 for the A and B chains, respectively (S1 Table)] indicates that both conformations of 10 are stably bound to TcDHODH. Moreover, a cryoprotectant glycerol molecule (GOL410) was found interacting with the naphthyl ring of the non-7-like mode and the O2 orotate pyrimidine ring of 10 (Fig 4C, right) in the B chain. In addition, GOL410 forms hydrogen bonds with the side chain hydroxyl group and main chain oxygen of S195 (Fig 4C, right). This finding indicates the possibility of developing more potent orotate derivatives using a fragment-based approach, which is now in progress.

Fig 4. Binding modes of the top 2 TcDHODH inhibitors designed in this study.

(A) Binding mode of 9 to chains A (left) and B (right); (B) Binding mode of 10 to the A chain; (C) Dual binding mode of 10 into the B chain. Left and right panels emphasize the interactions of 5-substituent groups from 7-like and non-7-like binding modes, respectively. Key residues within a 4.0 Å distance to 5-subtituents 9, 10, and FMN are shown as stick. Dashed line represents hydrophobic or hydrogen bond interaction. Atoms of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are colored in salmon, blue, and red, respectively. Electron density maps are shown as blue mesh and contoured at a 1 σ level.

Para-alkyl-phenylethyl orotate derivatives as novel Q-site inhibitors of HsDHODH

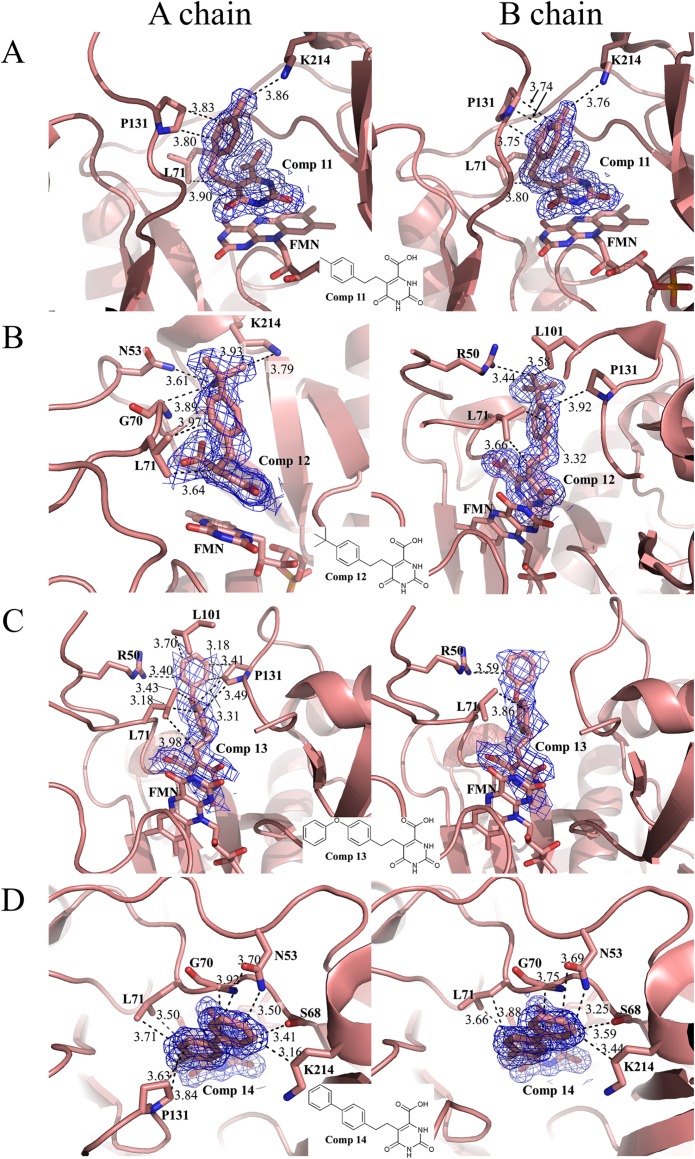

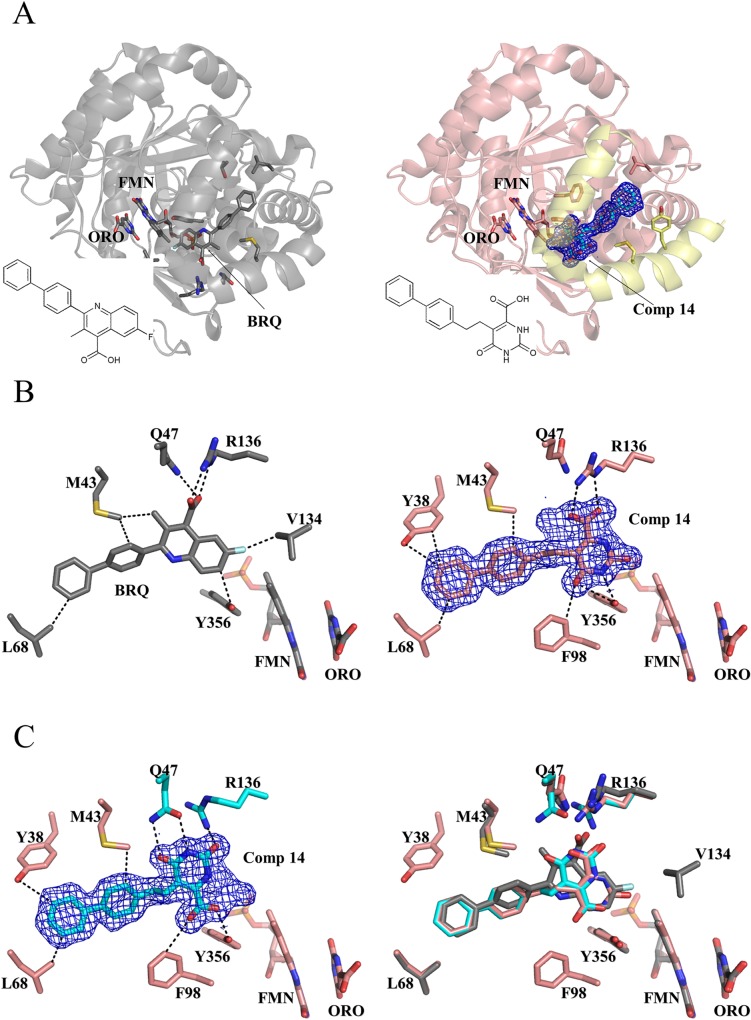

During the drug-design process, we found that four 5-phenylethyl orotate derivatives containing an alkylated substitution at the para position of the phenyl ring (11–14, Table 1) exhibited increased inhibition of HsDHODH (Table 1). Co-crystal structures show that 11–14 bind to the TcDHODH OF and interact with the hydrophobic region, as expected (Fig 5A to 5D). Because of the L71 to F149 substitution in HsDHODH, 11–14 were not predicted to inhibit HsDHODH. However, all four compounds showed remarkably decreased Kiapp against HsDHODH. In particular, 14 shows a Kiapp of 0.485 μM for HsDHODH and a very poor selectivity index (0.61). As a positive control for HsDHODH assays, the active metabolite of leflunomide, A771726, exhibited an IC50 of 0.38 μM (Kiapp = 0.19 μM) in our assay conditions, consistent with the reported Ki value of 0.18 μM[50]. To understand the structural basis of HsDHODH inhibition by 11–14, we obtained the co-crystal structure of 14 with HsDHODH and compared it to that of TcDHODH (S2 Table). Surprisingly, 14 did not bind to the orotate binding site. Instead, it was bound to the hydrophobic tunnel involved in the binding of ubiquinone (Q-site) at the N-terminal region (Fig 6A), which is absent in TcDHODH.

Fig 5.

Binding mode of Comp 11 (A), 12 (B), 13 (C) and 14 (D) into chains A (left) and B (right) of TcDHODH. Key residues within 4.0 Å distance to 5-subtituent groups, inhibitors and FMN are shown as stick. Dashed lines represent hydrophobic or hydrogen bond interactions between 5-substitutent and protein residues within 4.0 Å distance, which are shown as the number next to the respective interactions. Color codes are same as Fig 4. Electron density map of Comp 11–14 are shown as blue mesh and contoured at 1 σ level.

Fig 6. Overlapping binding site between brequinar analog and 14.

(A) Overall structure of HsDHODH complexed with brequinar analog (BRQ, left, gray, 1D3G) [18] and 14 (right, pink, 3W7R). The N-terminal region, which attaches the protein to the mitochondrial inner membrane and proposed to be the ubiquinone reduction site, is highlighted in yellow. (B) Binding modes of the brequinar analog (left, 1D3G)[18] and 14 (right). BRQ, 14, FMN, ORO, and key residues are shown in stick. Interactions within 3.5 Å are shown as dashed lines. Note the interaction of the carboxylate group from 14 with R136 (right), as in the BRQ analog (left), resulting in a “brequinar-like” binding mode. (C) The carboxylate group of 14 interacts with Y356 in a “non-brequinar-like” binding mode (left). BRQ and the dual binding modes of 14 were superposed in the right figure. Color codes for nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and fluorine are blue, red, dark yellow, and white, respectively. Carbon atoms from BRQ analog and 14 bound in a brequinar-like mode are gray and salmon, respectively. Carbon atoms from 14 and the two residues (Q47 and R136) that change their conformation in a non-brequinar-like binding mode are colored in cyan. The electron density map of 14 is shown as blue mesh and contoured at a 1 σ level.

Brequinar is a competitive inhibitor versus ubiquinone[51] for rat DHODH and the crystal structure of a brequinar analog-HsDHODH complex (Fig 6A) is available (1D3G)[18]. Comparison of crystal structures of HsDHODH in complex with 14 (Fig 6A, right) and a brequinar analog (Fig 6A, left) clearly shows that the binding sites of these inhibitors completely overlap (Fig 6B, left and Fig 6C, right). Interestingly, 14 bound the Q-site in dual mode, which are brequinar-like (Fig 6B, right) and non-brequinar-like (Fig 6C, left). In brequinar-like mode, the carboxylate group of 14 interacts with R136 (Fig 6A, right), while interacting with Y356 in non-brequinar-like mode (Fig 6B, left). This versatile property of the Q-site of HsDHODH, allowing binding of different conformations of carboxylated inhibitors, is consistent with the observations of Baungartner and colleagues[34]. Because of the structural similarity of 11–14, we can conclude that the decreased specificity is the result of binding at the Q-site and not to the orotate binding site of HsDHODH.

Correlation between docking scores and IC50

Finally, correlation analysis between in silico and inhibition studies of all 5-substituted orotate derivatives was performed (S5 Fig). The result clearly show that a good correlation between calculated docking scores and experimentally determined IC50s for all compounds designed in this study, thus validating our drug design methodology.

Conclusion

This study provides the first proof-of-concept for a rational determination of protein OF conformations a priori using the OF inducer approach, specifically for proteins containing flexible regions around their active site. We also show that determination of the OF structure at the early stage of SBDD constitutes a shortcut for obtaining nanomolar inhibitors.

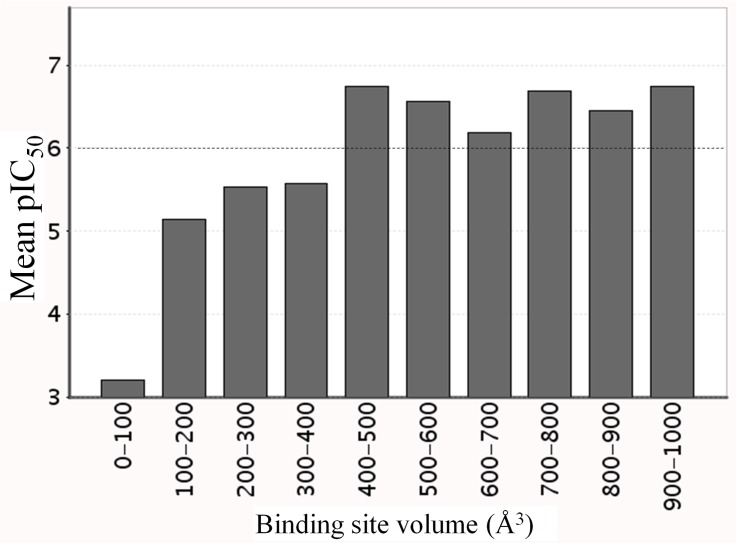

The X-ray analyses of ligand-free TcDHODH structures, as well as in complex with ligands, show that the L128-D142 loop functions as a lid, completely covering the active site (closed form). In silico screening based on the active site structure in the closed form failed to identify lead compounds that inhibit TcDHODH more potently than orotate (unpublished results). To explain this, a histogram correlating the inhibitor binding site volume versus IC50 was generated using over 3125 inhibitor-target complexes with known IC50s (from PDBbind). Binding site volumes > 400 Å3 are necessary to design inhibitors with nanomolar IC50 values (Fig 7). Because of the small volume (178 Å3) of the TcDHODH closed form active site, the design of inhibitors targeting the active site was unrealistic.

Fig 7. Histogram correlating the volume of inhibitor’s binding site versus pIC50, generated using ca. 3000 inhibitor/target complex structures with known IC50s from PDBbind data base.

Dashed line represents the threshold between micromolar and nanomolar order inhibitor.

Successful examples of SBDD targeting protein-protein interaction (PPI) sites (ex. Bcl-2 family proteins)[52],[53],[23], allosteric sites (ex. G-protein-coupled receptor)[54], or active sites (ex. human and P. falciparum DHODHs)[33],[55] have been reported. The crucial prerequisite for targeting PPI sites is the necessity of protein subunit association for biological function in the target protein. Enzymes belonging to family 1A are homodimeric and inhibitors targeting the interface between monomers may be attractive sites for drug design. However, evidence from size-exclusion chromatography, activity staining and dynamic light scattering indicate that the PPI approach was not applicable to TcDHODH, which functions in monomeric form and becomes homodimeric at high concentrations only (S6 and S7 Figs and S3 Table).

Difficulties in obtaining the OF structure of a target protein with the small volume of a drug binding pocket, are common problems encountered during drug-design. In this study we show that TcDHODH has a small active site and is the first monomeric enzyme among reported family 1A DHODHs. From a practical standpoint, conventional approaches for drug design were not applicable for TcDHODH. We have previously reported that TcDHODH contains a highly flexible active site loop composed of residues from L128 to D142, as demonstrated by the ligand-free structure[16]. Additionally, the co-crystal structures with different ligands could be easily obtained by soaking method. This has made TcDHODH an ideal model to design potent inhibitors using the OF inducer approach.

Because of the high conservation of residues forming the small active site pocket among T. cruzi and human DHODHs, the design of a specific and potent inhibitor was difficult. Using the OF inducer approach, we obtained the OF structure of TcDHODH and showed that many residues surrounding the active site are specific for TcDHODH. By targeting the active site structure with OF, we show the first successful demonstration of the design of potent and selective inhibitors of a family 1A DHODH. The OF inducer approach will contribute to the development of new drugs against Chagas disease, and represents a powerful new tool for drug design. This approach has potential to encourage drug design against diseases where the molecular targets are such difficult proteins possessing small AS volume.

Supporting Information

(A) Without the effect of an open-form inducer (chain A of PDB ID 2E6F), (B) in the open form due to 1 interaction (chain A of PDB ID 3W1Q) and c chain B of PDB ID 3W1Q showing higher enlargement of active site due to additional effect of crystal packing. Protein backbone is represented as gray (chain A) and dark gray (chain B) ribbons with the residues L128-D142 (active loop) as red ribbon. Sites regions were identified using CASTp Server[56] and Figures produced with UCSF Chimera[57].

(TIF)

The surrounding amino acid residues which become exposed by the active site loop movement are represented in stick. The movement of the active site loop make exposed hydrophobic region (formed by G70, L71, L101 and P131) and hydrogen bonding sites such as R50, N53, S68, S195, N198 and K214. Color codes are the same as Fig 2C except for the active site loop where carbon atoms were colored in orange. Electron density map, contoured at 1 σ, from Comp 1 is shown.

(TIF)

Predicted and co-crystallized binding modes of 2 (A), 3 (B), 4 (C) and 5 (D) are shown in left and right panels, respectively. Hydrophobic interactions of 5-substituents with P131 (2–5) or G70 (4) are shown as dashed lines labeled by their distance (Å). Residues P131 and G70, 2–5 and FMN are represented by stick. Atoms of nitrogen and oxygen are colored in blue and red, respectively. Carbons from predicted and co-crystallized structures are shown in gray and salmon, respectively. Electron density map from 2–5 co-crystallized with TcDHODH (right panels) are shown as blue mesh and contoured at 1 σ level.

(TIF)

Binding mode of 6 (A), 7 (B) and 8 (C) into chains A (left) and B (right). Key residues within 4 Å distance to 5-subtituent groups, 6, 7, 8 and FMN are shown as stick. Dashed lines represent the hydrophobic or hydrogen bond interactions between 5-substitutent and protein residues with distances (Å) shown as number next to the respective interactions. Atoms of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen are colored in salmon, blue, and red, respectively. Electron density map of Comp 6–8 are shown as blue mesh and contoured at 1σ level.

(TIF)

1, 5 and 9 were removed for better visualization of graph since their position overlaps with others.

(TIF)

The size of TcDHODH was estimated using TSK G3000SW (Tosoh) gel filtration column (7.5 × 600 mm). Purified TcDHODH was mixed with 50 ml Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-Rad) to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and injected to the column. The analysis was performed at room temperature at flow rate of 1 ml/min in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.25 mM sodium orotate. The molecular weight of TcDHODH was calculated based on the retention time of size markers that are: A-Void peak; B-Thyroglobulin (670 kDa); C-γ-globulin (158 kDa); D-Ovalbumin (44 kDa); E-Myoglobin (17 kDa) and F-Vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa). The black arrow indicates the peak corresponding to TcDHODH (37 kDa, as calculated from the standards).

(TIF)

Left, blue native PAGE of TcDHODH followed by DHODH activity staining. 1250 to 20 ng of pure TcDHODH was applied onto 4–16% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V constant by light blue cathode buffer method (0.002% of G-250 blue dye) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Right, high resolution clear native electrophoresis of HsDHODH followed by DHODH activity staining. 1250 to 50 ng of purified HsDHODH was loaded onto 4–16% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V constant according to manufacturer instruction. The DHODH activity of TcDHODH and HsDHODH was stained as described in Material and Methods.

(TIF)

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. *, PF: Photon factory and SP8: SPring-8.

(DOCX)

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. *, PF: Photon factory.

(DOCX)

a, estimated molecular weight. For detailed Method, see reference [15] from main text.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using synchrotron beamlines BL44XU and BL41XU at Spring-8, and beamlines BL5A, BL17A, NE3A, and NW12A at Photon Factory. We thank all beamline staff members for their help with X-ray diffraction data collection. This work was supported in part by Creative Scientific Research Grant 18GS0314 (to K.K.), Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research 18073004 and 26253025 (to K.K.), 26870119 and 16K19114 (to D.K.I.) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, and Targeted Proteins Research Program (to K.K. and Sh.H.) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, Sports and Technology (MEXT). We also acknowledge the support from Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Food Industry (to K.K. and Sh.H.) and JST/ JICA, SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development) 10000284 (to K.K.) and 1400738 (to D.K.I.).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by Creative Scientific Research Grant 18GS0314 (to K.K.), Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research 18073004 and 26253025 (to K.K.), 26870119 and 16K19114 (to D.K.I.) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, and Targeted Proteins Research Program (to K.K. and Sh.H.) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, Sports and Technology (MEXT). The authors also acknowledge the support from Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Food Industry (to K.K. and Sh.H.) and JST/ JICA, SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development) 10000284 (to K.K.) and 1400738 (to D.K.I.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fox RI, Herrmann ML, Frangou CG, Wahl GM, Morris RE, Strand V, et al. Mechanism of action for leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Immunol. 1999;93(3):198–208. Epub 1999/12/22. 10.1006/clim.1999.4777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breedveld FC, Dayer JM. Leflunomide: mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(11):841–9. Epub 2000/10/29. 10.1136/ard.59.11.841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rozencweig M, Von Hoff DD, Cysyk RL, Muggia FM. m-AMSA and PALA: two new agents in cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1979;3(3):135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyde JE. Targeting purine and pyrimidine metabolism in human apicomplexan parasites. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8(1):31–47. Epub 2007/02/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copeland RA, Marcinkeviciene J, Haque TS, Kopcho LM, Jiang W, Wang K, et al. Helicobacter pylori-selective antibacterials based on inhibition of pyrimidine biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(43):33373–8. Epub 2000/08/12. 10.1074/jbc.M004451200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond DJ, Gutteridge WE. UMP synthesis in the kinetoplastida. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;718(1):1–10. Epub 1982/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Sayed NM, Myler PJ, Bartholomeu DC, Nilsson D, Aggarwal G, Tran AN, et al. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science. 2005;309(5733):409–15. Epub 2005/07/16. 10.1126/science.1112631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arakaki TL, Buckner FS, Gillespie JR, Malmquist NA, Phillips MA, Kalyuzhniy O, et al. Characterization of Trypanosoma brucei dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a possible drug target; structural, kinetic and RNAi studies. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(1):37–50. Epub 2008/03/04. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06131.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong HB, Sienkiewicz N, Wyllie S, Patterson S, Fairlamb AH. Trypanosoma brucei (UMP synthase null mutants) are avirulent in mice, but recover virulence upon prolonged culture in vitro while retaining pyrimidine auxotrophy. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90(2):443–55. Epub 2013/08/29. 10.1111/mmi.12376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali JA, Tagoe DN, Munday JC, Donachie A, Morrison LJ, de Koning HP. Pyrimidine biosynthesis is not an essential function for Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58034 Epub 2013/03/19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson ZN, Gilroy CA, Boitz JM, Ullman B, Yates PA. Genetic dissection of pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage in Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(16):12759–70. Epub 2012/03/01. 10.1074/jbc.M112.346502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annoura T, Nara T, Makiuchi T, Hashimoto T, Aoki T. The origin of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase genes of kinetoplastids, with special reference to their biological significance and adaptation to anaerobic, parasitic conditions. J Mol Evol. 2005;60(1):113–27. Epub 2005/02/08. 10.1007/s00239-004-0078-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto M, Morales J, Fukai Y, Suzuki S, Takamiya S, Tsubouchi A, et al. Critical importance of the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway for Trypanosoma cruzi growth in the mammalian host cell cytoplasm. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(3):1002–6. Epub 2012/01/03. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen KFaB O. Evolutionary and functional families of dihydroorotate dehydrogenases. Paths to Pyrimidines. 1998;6(1):20–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takashima E, Inaoka DK, Osanai A, Nara T, Odaka M, Aoki T, et al. Characterization of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a soluble fumarate reductase in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;122(2):189–200. Epub 2002/07/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaoka DK, Sakamoto K, Shimizu H, Shiba T, Kurisu G, Nara T, et al. Structures of Trypanosoma cruzi dihydroorotate dehydrogenase complexed with substrates and products: atomic resolution insights into mechanisms of dihydroorotate oxidation and fumarate reduction. Biochemistry. 2008;47(41):10881–91. Epub 2008/09/24. 10.1021/bi800413r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowland P, Norager S, Jensen KF, Larsen S. Structure of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B: electron transfer between two flavin groups bridged by an iron-sulphur cluster. Structure. 2000;8(12):1227–38. Epub 2001/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Neidhardt EA, Grossman TH, Ocain T, Clardy J. Structures of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in complex with antiproliferative agents. Structure. 2000;8(1):25–33. Epub 2000/02/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nihei C, Fukai Y, Kita K. Trypanosome alternative oxidase as a target of chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1587(2–3):234–9. Epub 2002/06/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minagawa N, Yabu Y, Kita K, Nagai K, Ohta N, Meguro K, et al. An antibiotic, ascofuranone, specifically inhibits respiration and in vitro growth of long slender bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;84(2):271–80. Epub 1997/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yabu Y, Yoshida A, Suzuki T, Nihei C, Kawai K, Minagawa N, et al. The efficacy of ascofuranone in a consecutive treatment on Trypanosoma brucei brucei in mice. Parasitol Int. 2003;52(2):155–64. Epub 2003/06/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yabu Y, Suzuki T, Nihei C, Minagawa N, Hosokawa T, Nagai K, et al. Chemotherapeutic efficacy of ascofuranone in Trypanosoma vivax-infected mice without glycerol. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(1):39–43. Epub 2005/11/18. 10.1016/j.parint.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Garon EB, Ribeiro de Oliveira M, Bonomi PD, Camidge DR, et al. Phase II study of single-agent navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(11):3163–9. Epub 2012/04/13. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omura S, Miyadera H, Ui H, Shiomi K, Yamaguchi Y, Masuma R, et al. An anthelmintic compound, nafuredin, shows selective inhibition of complex I in helminth mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):60–2. Epub 2000/12/20. 10.1073/pnas.98.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto J, Sakamoto K, Shinjyo N, Kido Y, Yamamoto N, Yagi K, et al. Anaerobic NADH-fumarate reductase system is predominant in the respiratory chain of Echinococcus multilocularis, providing a novel target for the chemotherapy of alveolar echinococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(1):164–70. Epub 2007/10/24. 10.1128/AAC.00378-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyadera H, Shiomi K, Ui H, Yamaguchi Y, Masuma R, Tomoda H, et al. Atpenins, potent and specific inhibitors of mitochondrial complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(2):473–7. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC141019. 10.1073/pnas.0237315100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiba T, Kido Y, Sakamoto K, Inaoka DK, Tsuge C, Tatsumi R, et al. Structure of the trypanosome cyanide-insensitive alternative oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):4580–5. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3607012. 10.1073/pnas.1218386110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osanai A, Harada S, Sakamoto K, Shimizu H, Inaoka DK, Kita K. Crystallization of mitochondrial rhodoquinol-fumarate reductase from the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum with the specific inhibitor flutolanil. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2009;65(Pt 9):941–4. Epub 2009/09/03. 10.1107/S1744309109031352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu H, Osanai A, Sakamoto K, Inaoka DK, Shiba T, Harada S, et al. Crystal structure of mitochondrial quinol-fumarate reductase from the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. J Biochem. 2012;151(6):589–92. Epub 2012/05/12. 10.1093/jb/mvs051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harada S, Inaoka DK, Ohmori J, Kita K. Diversity of parasite complex II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(5):658–67. Epub 2013/01/22. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inaoka D, Shiba T, Sato D, Balogun E, Sasaki T, Nagahama M, et al. Structural Insights into the Molecular Design of Flutolanil Derivatives Targeted for Fumarate Respiration of Parasite Mitochondria. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(7):15287 10.3390/ijms160715287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritzson I, Svensson B, Al-Karadaghi S, Walse B, Wellmar U, Nilsson UJ, et al. Inhibition of human DHODH by 4-hydroxycoumarins, fenamic acids, and N-(alkylcarbonyl)anthranilic acids identified by structure-guided fragment selection. ChemMedChem. 2010;5(4):608–17. Epub 2010/02/26. 10.1002/cmdc.200900454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies M, Heikkila T, McConkey GA, Fishwick CW, Parsons MR, Johnson AP. Structure-based design, synthesis, and characterization of inhibitors of human and Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenases. J Med Chem. 2009;52(9):2683–93. Epub 2009/04/09. 10.1021/jm800963t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumgartner R, Walloschek M, Kralik M, Gotschlich A, Tasler S, Mies J, et al. Dual binding mode of a novel series of DHODH inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2006;49(4):1239–47. Epub 2006/02/17. 10.1021/jm0506975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coteron JM, Marco M, Esquivias J, Deng X, White KL, White J, et al. Structure-guided lead optimization of triazolopyrimidine-ring substituents identifies potent Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors with clinical candidate potential. J Med Chem. 2011;54(15):5540–61. Epub 2011/06/24. 10.1021/jm200592f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gujjar R, Marwaha A, El Mazouni F, White J, White KL, Creason S, et al. Identification of a metabolically stable triazolopyrimidine-based dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor with antimalarial activity in mice. J Med Chem. 2009;52(7):1864–72. Epub 2009/03/20. 10.1021/jm801343r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips MA, Rathod PK. Plasmodium dihydroorotate dehydrogenase: a promising target for novel anti-malarial chemotherapy. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10(3):226–39. Epub 2010/03/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heikkila T, Ramsey C, Davies M, Galtier C, Stead AM, Johnson AP, et al. Design and synthesis of potent inhibitors of the malaria parasite dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):186–91. Epub 2007/01/19. 10.1021/jm060687j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teague SJ. Implications of protein flexibility for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(7):527–41. Epub 2003/07/03. 10.1038/nrd1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferguson KA. Starch-Gel Electrophoresis—Application to the Classification of Pituitary Proteins and Polypeptides. Metabolism. 1964;13:SUPPL:985–1002. Epub 1964/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chemical Computing Group Inc. SSW, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2012.10. 2012.

- 42.Pipeline Pilot; Accelrys Software Inc.: San Diego California U. Pipeline Pilot; Accelrys Software Inc.: San Diego California, USA. 2007.

- 43.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47(7):1739–49. Epub 2004/03/19. 10.1021/jm0306430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inaoka DK, Takashima E, Osanai A, Shimizu H, Nara T, Aoki T, et al. Expression, purification and crystallization of Trypanosoma cruzi dihydroorotate dehydrogenase complexed with orotate. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2005;61(Pt 10):875–8. Epub 2006/03/03. 10.1107/S174430910502659X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otwinowski ZaM W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276(part A):20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–32. Epub 2004/12/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–55. Epub 1997/05/01. 10.1107/S0907444996012255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheleski J, Rocha JR, Pinheiro MP, Wiggers HJ, da Silva AB, Nonato MC, et al. Novel insights for dihydroorotate dehydrogenase class 1A inhibitors discovery. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45(12):5899–909. Epub 2010/10/23. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology FE. MacDonald RLLaFM, editor: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis JP, Cain GA, Pitts WJ, Magolda RL, Copeland RA. The immunosuppressive metabolite of leflunomide is a potent inhibitor of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1996;35(4):1270–3. Epub 1996/01/30. 10.1021/bi952168g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLean JE, Neidhardt EA, Grossman TH, Hedstrom L. Multiple inhibitor analysis of the brequinar and leflunomide binding sites on human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2001;40(7):2194–200. Epub 2001/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435(7042):677–81. Epub 2005/05/20. 10.1038/nature03579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parikh SA, Kantarjian H, Schimmer A, Walsh W, Asatiani E, El-Shami K, et al. Phase II study of obatoclax mesylate (GX15-070), a small-molecule BCL-2 family antagonist, for patients with myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(4):285–9. Epub 2010/08/17. 10.3816/CLML.2010.n.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dror RO, Green HF, Valant C, Borhani DW, Valcourt JR, Pan AC, et al. Structural basis for modulation of a G-protein-coupled receptor by allosteric drugs. Nature. 2013;503(7475):295–9. Epub 2013/10/15. 10.1038/nature12595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bedingfield PT, Cowen D, Acklam P, Cunningham F, Parsons MR, McConkey GA, et al. Factors influencing the specificity of inhibitor binding to the human and malaria parasite dihydroorotate dehydrogenases. J Med Chem. 2012;55(12):5841–50. Epub 2012/05/25. 10.1021/jm300157n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W116–8. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1538779. 10.1093/nar/gkl282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–12. 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Without the effect of an open-form inducer (chain A of PDB ID 2E6F), (B) in the open form due to 1 interaction (chain A of PDB ID 3W1Q) and c chain B of PDB ID 3W1Q showing higher enlargement of active site due to additional effect of crystal packing. Protein backbone is represented as gray (chain A) and dark gray (chain B) ribbons with the residues L128-D142 (active loop) as red ribbon. Sites regions were identified using CASTp Server[56] and Figures produced with UCSF Chimera[57].

(TIF)

The surrounding amino acid residues which become exposed by the active site loop movement are represented in stick. The movement of the active site loop make exposed hydrophobic region (formed by G70, L71, L101 and P131) and hydrogen bonding sites such as R50, N53, S68, S195, N198 and K214. Color codes are the same as Fig 2C except for the active site loop where carbon atoms were colored in orange. Electron density map, contoured at 1 σ, from Comp 1 is shown.

(TIF)

Predicted and co-crystallized binding modes of 2 (A), 3 (B), 4 (C) and 5 (D) are shown in left and right panels, respectively. Hydrophobic interactions of 5-substituents with P131 (2–5) or G70 (4) are shown as dashed lines labeled by their distance (Å). Residues P131 and G70, 2–5 and FMN are represented by stick. Atoms of nitrogen and oxygen are colored in blue and red, respectively. Carbons from predicted and co-crystallized structures are shown in gray and salmon, respectively. Electron density map from 2–5 co-crystallized with TcDHODH (right panels) are shown as blue mesh and contoured at 1 σ level.

(TIF)

Binding mode of 6 (A), 7 (B) and 8 (C) into chains A (left) and B (right). Key residues within 4 Å distance to 5-subtituent groups, 6, 7, 8 and FMN are shown as stick. Dashed lines represent the hydrophobic or hydrogen bond interactions between 5-substitutent and protein residues with distances (Å) shown as number next to the respective interactions. Atoms of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen are colored in salmon, blue, and red, respectively. Electron density map of Comp 6–8 are shown as blue mesh and contoured at 1σ level.

(TIF)

1, 5 and 9 were removed for better visualization of graph since their position overlaps with others.

(TIF)

The size of TcDHODH was estimated using TSK G3000SW (Tosoh) gel filtration column (7.5 × 600 mm). Purified TcDHODH was mixed with 50 ml Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-Rad) to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and injected to the column. The analysis was performed at room temperature at flow rate of 1 ml/min in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.25 mM sodium orotate. The molecular weight of TcDHODH was calculated based on the retention time of size markers that are: A-Void peak; B-Thyroglobulin (670 kDa); C-γ-globulin (158 kDa); D-Ovalbumin (44 kDa); E-Myoglobin (17 kDa) and F-Vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa). The black arrow indicates the peak corresponding to TcDHODH (37 kDa, as calculated from the standards).

(TIF)

Left, blue native PAGE of TcDHODH followed by DHODH activity staining. 1250 to 20 ng of pure TcDHODH was applied onto 4–16% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V constant by light blue cathode buffer method (0.002% of G-250 blue dye) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Right, high resolution clear native electrophoresis of HsDHODH followed by DHODH activity staining. 1250 to 50 ng of purified HsDHODH was loaded onto 4–16% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 150 V constant according to manufacturer instruction. The DHODH activity of TcDHODH and HsDHODH was stained as described in Material and Methods.

(TIF)

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. *, PF: Photon factory and SP8: SPring-8.

(DOCX)

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. *, PF: Photon factory.

(DOCX)

a, estimated molecular weight. For detailed Method, see reference [15] from main text.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.