Abstract

Objective

This study examined the efficacy of motivational strategies for increasing engagement into evidence-based, parenting interventions delivered through schools.

Method

Participants were 122 mothers of kindergarten and third grade students attending an urban school that predominantly served Mexican American families living in low-income conditions. At pre-test mothers reported sociocultural characteristics, and teachers rated children’s behavior. Mothers randomly assigned to the experimental condition received a multi-component engagement package; mothers assigned to the control condition received a brochure plus a non-engagement survey interview. All families were offered a free parenting program delivered at their child’s school. Dependent variables included parenting program enrollment, initiation (i.e., attending at least one session), and attendance.

Results

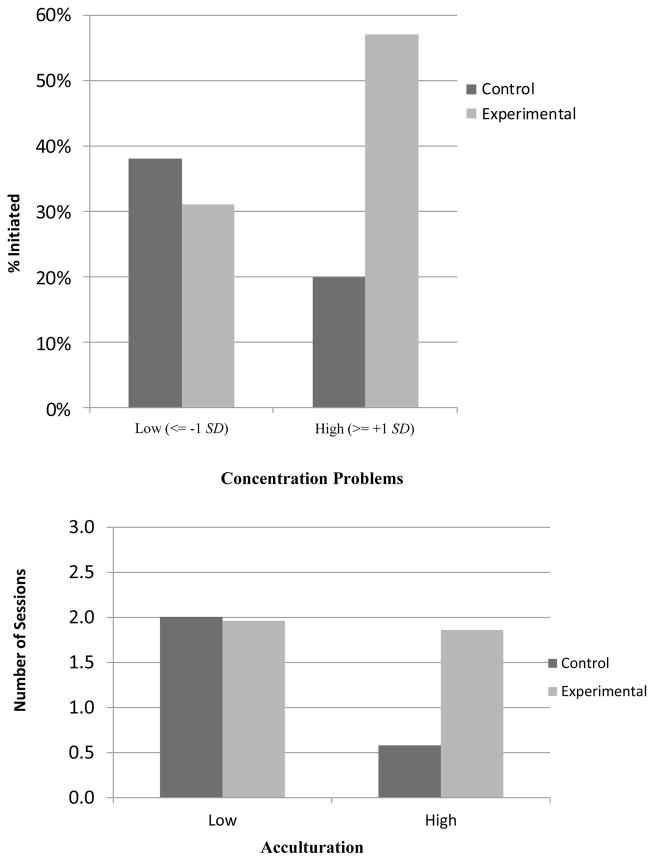

Parents in the experimental condition were more likely to initiate compared to those in the control condition if their children had high baseline concentration problems; OR = 8.98, p < .001, 95% CI [2.55, 31.57]. Parents in the experimental condition attended more sessions than those in the control condition if their children had high baseline concentration problems, p < .01, d = .49, 95% CI [.35, 2.26]; or conduct problems, p < .01, d = .54, 95% CI [.51, 2.56]. Highly acculturated parents attended more sessions if assigned to the experimental condition than the control condition, p < .01, d = .66, 95% CI [.28, 2.57].

Conclusions

The motivational engagement package increased parenting program initiation and attendance for parents of students at-risk for behavior problems.

Keywords: engagement, attendance, parenting, prevention, Latino

Children in impoverished, urban neighborhoods are often exposed to multiple adversities (e.g., Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003) that place them at risk for behavior problems (Santiago, Wadsworth, & Stump, 2011; Winslow & Shaw, 2007). Elevated behavior problems among children in low-income, urban neighborhoods begin to emerge in early elementary school (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Winslow & Shaw, 2007) and lead to increased risk for externalizing and substance use problems in adolescence and adulthood (Dodge et al., 2009; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2009). For example, early teacher-reported conduct problems have predicted adolescent violence (Petras, Chilcoat, Leaf, Ialongo, & Kellam, 2004) and more negative outcomes in young adulthood; such as early pregnancy, unemployment, school dropout, substance use, and criminality (Bradshaw, Schaeffer, Petras, & Ialongo, 2010; Schaeffer, Petras, Ialongo, Poduska, & Kellam, 2003). Controlling for conduct problems, gender and race, high concentration problems at school entry have differentiated boys with increasing aggression from boys with stable low aggression from first to seventh grade (Schaeffer et al., 2003).

Thus, early elementary school is a critical time to intervene to prevent the development and escalation of behavior problems for children in low-income, urban neighborhoods. Evidence-based parenting programs have shown great promise for decreasing and preventing behavior problems (Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008; Sandler, Schoenfelder, Wolchik, & MacKinnon, 2011). Several researchers have shown that children in low-income, urban communities with elevated behavior problems benefit more from parenting interventions than those with low behavior problems within the same communities (e.g., Gonzales et al., 2012; Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Baydar, 2004). Thus, delivering preventive parenting programs in elementary schools that serve a large number of families experiencing poverty, and particularly engaging those already showing elevated behavior problems, provides an excellent opportunity for preventing the development and escalation of behavior problems in these communities.

Despite the promise of evidence-based parenting programs for preventing child behavior problems, to date, engagement in school- or community-based parenting programs has been too low to have a meaningful public health impact because typically less than 20% attend at least one session (Fagan, Hanson, Hawkins, & Arthur, 2009; Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond, & Shin, 2007). Children suffer when their parents do not participate in evidence-based parenting programs. For example, in a sample of children attending Head Start, Reid and colleagues (2004) found that children with high teacher-rated behavior problems whose mothers chose not to attend the Incredible Years parenting program, or who were randomly assigned not to attend, showed escalations in behavior problems from pre- to post-parent training; whereas children with high behavior problems whose mothers participated showed decreases in behavior problems to normative levels. Thus, low parental engagement in evidence-based parenting programs puts young children at risk for escalated behavior problems.

Some sociocultural groups have been more difficult to engage than others. Single-parent families, those of low socioeconomic status, and some ethnic minority subgroups have been particularly unlikely to engage in parenting programs (Baker, Arnold, & Meagher, 2011; Carpentier et al., 2007; Dumka, Garza, Roosa, & Stoerzinger, 1997; Winslow, Bonds, Wolchik, Sandler, & Braver, 2009). For example, highly acculturated (e.g., monolingual English-speaking), Mexican American parents in low-income communities have been less likely to enroll and attend school-based family prevention programs than low acculturated (e.g., monolingual Spanish-speaking), Mexican American parents in the same communities (Carpentier et al., 2007; Dumka et al., 1997). This is particularly problematic, because highly acculturated, Mexican American youths are at elevated risk for a range of poor outcomes, including behavior problems, compared to their low acculturated peers, non-Hispanic White youths, and in some cases other ethnic minority groups (Alegría et al., 2008; Gonzales, Jensen, Montano, & Wynne, 2014). Thus, it is critically important to develop strategies that are effective at engaging highly acculturated, Mexican American families in low-income, urban communities.

Some researchers have reported anecdotal success at recruiting and retaining Latino families using community-based participatory research practices and culturally grounded engagement strategies (e.g., Dumka et al., 1997; Eakin et al., 2007). For example, Reidy, Orpinas, and Davis (2012) used the following strategies to engage Latino families into a Spanish-language adaptation of the Strengthening Families Program, Familias Fuertes: 1) involved community members as gatekeepers, liaisons, and program facilitators; 2) employed bilingual and bicultural program facilitators; 3) adapted materials (e.g., consents, brochures) to be culturally appropriate; 4) fostered personal contact with participants through face-to-face recruitment meetings, weekly reminder calls or visits, and family-style dinners before sessions; and 5) held sessions at convenient locations and times, offered free child care, and provided cash incentives for attending sessions. Using these strategies, the researchers attained 100% enrollment of the 12 families approached for participation and 92% completed the program.

Although supported by anecdotal evidence, these strategies have not been experimentally tested in a randomized trial. Furthermore, methods included resource-intensive strategies, such as home visits and monetary incentives, which are not feasible to implement on a wide scale. Moreover, the strategies have been primarily geared toward barriers experienced by low acculturated, Latino community members (e.g., language barriers, violations of traditional Latino values). It is unclear if these strategies are sufficient for engaging highly acculturated, Mexican American parents, who have been less likely to attend parenting interventions than their low acculturated peers (Carpentier et al., 2007; Dumka et al., 1997).

Although experimental studies of brief phone and in-person motivational strategies have been shown to increase attendance at child mental health treatment sessions for Latino and other ethnic minority parents (Coatsworth, Santisteban, McBride, & Szapocznik, 2001; McKay, Stoewe, McCadam, & Gonzales, 1998; Nock & Kazdin, 2005); to date, there have been few systematic attempts to evaluate parenting program engagement strategies for parents who are not seeking services. A few researchers have studied the effects of providing incentives on attendance, and most have reported disappointing results (Dumas, Begle, French, & Pearl, 2010; Gross et al., 2011). In the only published, experimental prevention study that tested motivational enhancement techniques, Shephard, Armstrong, Silver, Berger, and Seifer (2012) reported preliminary results suggesting that a two-session, in-home motivational interviewing intervention increased engagement into the Incredible Years parenting program: 53% of parents in the motivational interviewing condition initiated (i.e., attended at least one session) compared to 33% in the control condition. Although these findings are encouraging, a two-session, in-home engagement intervention may be cost-prohibitive and thus difficult to implement on a wide scale.

Engagement Package Development

In this study, our objective was to develop an engagement package that would be feasible to implement under real-word conditions and test its effectiveness at increasing engagement into a parenting program that has been shown to prevent child behavior problems. We combined two approaches for developing the engagement package: 1) theory-based approach for strategy development and 2) community-based participatory approach for strategy refinement.

First, to construct a parent engagement framework and develop prototypes of engagement strategies, we used a theory-based approach widely advocated in the prevention field (e.g., National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Sandler, Wolchik, MacKinnon, Ayers, & Roosa, 1997). This approach involved designing strategies to change modifiable constructs known to predict engagement. Modifiable constructs of engagement and change strategies were identified using literature reviews of relevant disciplines (e.g., child mental health treatment, motivational and social psychology, health promotion research, and social marketing).

Second, to ensure that engagement strategies were culturally relevant for Mexican American families, we used community-based participatory research practices. Specifically, we formed an advisory board of parents, teachers, and school administrators from an elementary school in a poverty-stricken, urban neighborhood where the majority of residents were of Mexican descent. The board provided feedback on engagement protocols and materials and suggested additional engagement strategies to incorporate. Parents on the board delivered engagement strategies as part of a small pilot study with 15 parents of children attending the school. Refinements were made to the strategies based on feedback from parents who were engagers and parents who participated in the pilot. For example, consistent with the Latino cultural value of maintaining hierarchical relationships (i.e., respeto) (Marín & Marín, 1991), advisory board parents expressed a strong preference for engagement strategies to be conducted by a person of higher authority than themselves (e.g., group leader or teacher). Parents who participated in the pilot indicated that they would only attend the program if they heard from teachers and parents who had been in the program that it was helpful. Thus, engagement strategies were modified or added to address these and other recommendations. The resulting engagement package included four components—family testimonial flyer, teacher endorsement, group leader engagement call, and brochure—with multiple strategies per component.

Parent Engagement Framework

Figure 1 shows the modifiable constructs targeted in the parent engagement framework, and strategies designed to change them. Although we incorporated constructs and strategies from multiple theories relevant to engagement, we drew primarily from the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), given considerable research showing it predicts engagement in health behaviors, and that change strategies based on the theory are effective (e.g., McEachan, Conner, Taylor, & Lawton, 2011; Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, 2010). The theory of planned behavior posits three primary constructs that determine intentions and behavior: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control. Specifically, it is expected that people will engage in a behavior, like attend a parenting program, if they hold favorable beliefs about the behavior (attitudes), perceive social pressure to perform the behavior (subjective norms), and believe the behavior would be easy to do (perceived control) (Ajzen, 1991). (In the parent engagement framework, subjective norms is included under the broader construct of social factors).

Figure 1.

Parent engagement framework: Modifiable constructs and the strategies used to target each construct. Strategies in regular text were implemented only in the experimental condition. Strategies in bold were implemented in both conditions.

Attitudes

Attitudes (i.e., expectancies, perceived credibility, and perceived benefits) have predicted parenting program enrollment and attendance (Corso, Fang, Begle, & Dumas, 2010; Nock, Ferriter, & Holmberg, 2007; Nock & Kazdin, 2001; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2000; Wellington, White, & Liossis, 2006). For example, perceived benefits of an intervention predicted preventive parenting program enrollment and attendance, accounting for the effects of other predictors (e.g., current child behavior problems, demographic variables) (Corso et al., 2010; Spoth et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 1, the engagement package targeted parental attitudes in multiple ways, including providing testimonials about the positive outcomes parents obtained from the parenting program (family testimonial flyer), talking with parents about how their children would benefit (teacher endorsement), and eliciting parents’ goals for their family and showing how the program can help them attain them (group leader engagement call).

Social factors

Subjective norms are formed as a result of one’s beliefs about whether or not important referents (i.e., individuals with whom one is motivated to comply) would approve of one’s engagement in a behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Important referents often include legitimate authority figures (e.g., teachers) or peers who socially validate the behavior (Cialdini, 2001). For example, White and Wellington (2009) found that parents who intended to participate in a parenting program were more likely than non-intenders to believe that important referents (e.g., peers, spouse, family) would approve of their participation and would participate themselves. People are also more likely to engage if they have made a commitment to do so (Cialdini, 2001). Social factors were targeted by incorporating endorsements from parents and children (testimonial flyer) and teachers (teacher endorsement). In the engagement call, group leaders encouraged commitment by asking enrollees to complete, sign, and return an enrollment form.

Perceived control

We conceptualized perceived control in two ways—perceived control to do the program and perceived control to impact the child or family. White and Wellington (2009) found that parents with high perceived control to do a parenting intervention had higher intentions to attend than those with low perceived control. Also, Dumka and colleagues (1997) found that parents who believed they could impact their children’s adjustment were more interested in participating in preventive parenting programs. As shown in Figure 1, perceived control to do the intervention was targeted in the engagement call by building parents’ perceived efficacy to attend through successful problem solving of obstacles, which was guided by the group leader. Perceived control to impact the child/family was targeted in the testimonial flyer through reports of the positive changes parents made in their children’s behavior and family relationships by participating in the parenting program. In the engagement call, group leaders described the positive changes other parents reported after attending the program.

Obstacles and Planning

Perceived obstacles are an important antecedent of perceived control. People who perceive fewer obstacles to engaging in a behavior typically have greater perceived control over the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Obstacles to attending group-based parenting programs include logistical barriers, such as scheduling conflicts, lack of transportation, and childcare; as well as interpersonal barriers, such as mistrust of providers, fears of stigmatization, and privacy concerns (Axford, Lehtonen, Kaoukji, Tobin, & Berry, 2012). Perceived obstacles have predicted parenting program enrollment and attendance; controlling for other child, parent, and family variables (e.g., Spoth et al., 2000; Wellington et al., 2006). Researchers have also found that individuals are more likely to engage in new behaviors or interventions if they have developed implementation intentions, which are plans detailing where, when, and how they will engage, including how they will overcome specific obstacles if they arise (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). The bolded strategies in Figure 1 were used to reduce obstacles for all families (control and experimental). In the experimental group, parents also received an engagement call that targeted interpersonal barriers through the use of active listening techniques, and logistical barriers through guided problem solving of obstacles and implementation intentions planning.

Exposure

The amount and frequency of exposure (i.e., repeat exposure) has predicted health behavior change and maintenance (Hornik, 2002). We targeted repeat exposure by including more cues to action (testimonial flyer, teacher recommendation, engagement call, and reminders) in the experimental than control group. Also, based on research showing that people are more likely to act on highly salient goals (Abraham & Sheeran, 2003), the goal review in the engagement call was designed to increase the salience of parents’ program-relevant goals.

Current Study

In this study we experimentally evaluated the efficacy of the engagement package for increasing participation in the group level 4 Triple P Positive Parenting Program (Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, & Day, 2014). Participants were parents of children attending an elementary school in a highly poverty-stricken, urban neighborhood where the majority of residents were of Mexican descent. The Triple P program was chosen for several reasons: 1) Triple P’s effectiveness in improving positive parenting practices, preventing and treating early child behavior problems, and enhancing parental well-being has been demonstrated in meta-analyses of randomized trials (Sanders et al., 2014), including meta-analyses conducted by investigators not associated with the program’s development (e.g., Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008); 2) Triple P was designed for young children, the project’s target population; 3) Program materials were available in Spanish and English; and 4) Our advisory board of parents and teachers selected Triple P over other evidence-based programs due to its mix of group and individual phone sessions and moderate length. We chose to implement level 4, rather than levels 1, 2 or 3, so that results would generalize to other evidence-based parenting programs, which typically include 8 to 12 sessions. Although originally designed for children with behavior problems, the group level 4 program has been implemented as a universal program in multiple studies (Sanders et al., 2014).

We experimentally tested the effects of the engagement package on three aspects of engagement: enrollment (i.e., signing up), initiation (i.e., attending at least one session), and attendance (i.e., number of sessions attended). We examined enrollment because researchers have found that when offered, most parents do not enroll in preventive parenting programs (e.g., Heinrichs, Bertram, Kuschel, Hahlweg, 2005). We examined initiation, because many people who enroll never attend. This “intention-behavior gap” has been observed in the preventive parenting field (Baker et al., 2011), as well as more broadly in health promotion research (Webb & Sheeran, 2006). We also examined attendance, because half or more of parents who initiate do not complete the program or attend irregularly (Heinrichs et al., 2005; Ingoldsby, 2010).

The objective of this study was to test the main and interactive effects of the engagement package. First, we hypothesized that enrollment, initiation, and attendance would be higher among families assigned to the experimental than control condition. Second, we hypothesized that the engagement package would be more effective for parents of children with higher behavior problems because the strategies, such as goal-matching in the engagement call and providing personalized reasons for attending in the teacher endorsement, were designed to show parents whose children were experiencing problems that the program would be especially well-suited for their needs. Third, based on prior research we expected that children of highly acculturated parents would have more behavior problems than children of low acculturated, Mexican American parents (Gonzales et al., 2014) and that highly acculturated parents would be less likely to engage (Carpentier et al., 2007; Dumka et al., 1997). We hypothesized that the engagement package would be more effective for highly acculturated, Mexican American parents, because motivational strategies may be required to convince most highly acculturated parents to attend but may be less necessary for low acculturated parents who are more eager to participate. Fourth, we examined whether grade level (kindergarten vs. third grade) moderated engagement package effects. During transitions individuals often re-prioritize existing goals and develop new goals associated with the transition (Zirkel & Cantor, 1990). In prior work (BLOCKED FOR REVIEW), we found that divorced parents attended more sessions when they were offered a parenting intervention near the time of divorce than when it was offered a year or two after the divorce transition occurred. Thus, during the transition to elementary school (i.e., kindergarten), parents might be more likely to take advantage of a parenting program than parents of children who have already transitioned (i.e., third grade). If so, engagement package effects may be more pronounced for parents of third grade students, because motivational strategies may be needed to convince them to engage.

Method

A randomized controlled trial of the engagement package was conducted with two annual cohorts of data collection, engagement strategies, and Triple P delivery. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the [BLOCKED FOR REVIEW] Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Recruitment

Families were recruited from an elementary school in a poverty-stricken, urban neighborhood. The school’s ethnic composition was 97% Latino, 50% of the students were English language learners, and 92% qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. Consistent with schools’ typical “Opt Out” procedures and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99), teachers sent home opt out forms for parents to return if they did not want the school to share their contact information with the research team; 10% of families returned this form. After removing these names, 160 students were randomly selected by lottery from kindergarten and third grade rosters, blocking on student grade and primary language. Parents were sent a letter that described the research and included an endorsement memo from the school principal along with $2 compensation to talk about the study over the phone. Letters were followed by a phone call from a professionally trained, bilingual staff member to explain the study and determine eligibility and interest. Although both parents (in married/partnered families) were invited to participate in the Triple P program, only mothers were recruited for interviews due to limited resources, the desire to avoid non-independence bias, and feedback from fathers in our pilot study that mothers should do these interviews (consistent with traditional gender roles, marianismo and machismo) (Marín & Marín, 1991). Mothers were eligible if they spoke English or Spanish, had a biological/adopted child at this school, were not planning to change schools during the year, and the child lived with the mother at least half the time. Twelve families were ineligible and excluded from the study because the target child did not live with the biological/adoptive mother (n = 4), or the target child had changed schools (n = 4) or would be changing schools during the year (n = 4). In addition, one student was excluded because the child’s mother was already participating (i.e., the family had two eligible children).

Sample composition

As shown in Figure 2, of the 160 families randomly selected for recruitment, 122 (76%) completed the pre-test and were randomized to condition. Of the mothers, 95% self-identified as Latina, with 94% of Latinas self-identifying as Mexican or Mexican American. Racial composition was 89% White, 5% Native American, 5% Black/African American, and 1% multiracial. Fifty-nine percent of mothers had less than a high school education. Average family income was $22,524 per year.

Figure 2.

Participant Flowchart.

Procedure

Pre-test interview

All letters, protocols and measures were translated into Spanish using Marín and Marín’s (1991) back translation method. The 1-hour pre-test interview was conducted in the mother’s home or at the school, whichever she preferred. Interviews were conducted in the mother’s preferred language--65 interviews (53%) were conducted in Spanish and 57 (47%) were in English. After the interviewer read the informed consent form aloud and answered questions, mothers who chose to participate signed the consent form and received a copy. Consent forms and interview questions were read aloud to minimize potential reading difficulties. The interview included predominantly Likert-scale questionnaires of sociocultural background (demographics and acculturation), stress, perceived child problems, parenting practices, goals, opinions about parenting programs, participation barriers, and implementation intentions. Only portions of the interview relevant for testing our hypotheses were used in the current study. Mothers were compensated $50 for participating in the pre-test interview.

Randomization

After pre-test interviews, families were randomly assigned to the experimental engagement (n = 61) or control (n = 61) condition. The first author conducted the random assignment by lottery (i.e., picking out slips of paper). During informed consent, participants were told that they would be randomly assigned to one of two different ways of being invited to attend a parenting program; however, specific engagement strategies were not described. Pre-test interviews were conducted prior to randomization; thus, pre-test interviewers were blind to condition assignment. Non-engagement survey interviewers were also blind to condition because they had no knowledge of the participant’s condition assignment. The first author and engagers (i.e., teachers who distributed testimonial flyers and did endorsements; group leaders who did engagement calls and collected attendance) were not blind to condition.

Engagement strategies

Parents assigned to the experimental condition received all of the following engagement strategies; parents in the control condition received only the brochure.

Brochure

Brochures were mailed in school envelopes. Brochures provided information on the location, day and time of sessions; free childcare; topics covered; and availability of English or Spanish groups. An enrollment form and return envelope were included.

Family testimonial flyer

In the experimental condition, teachers included in students’ take home materials a testimonial flyer with photos and quotes from parents and children describing Triple P benefits and fun activities in childcare. The photos and quotes were obtained from families who participated in Triple P in the pilot study.

Teacher endorsement

Teachers endorsed Triple P through brief, unscripted conversations with parents in the experimental condition (or emails/notes home if personal contacts were unsuccessful). Given teachers’ limited time, this component was designed to be flexible (e.g., conducted with either parent; in-person or phone) and feasible, requiring less than 5 minutes per contact and using typical parent-teacher contact when possible (e.g., pick-up/drop-off). Training involved two 1-hour meetings. The first meeting familiarized teachers with Triple P and promoted buy-in by describing program benefits, especially ones teachers care most about (e.g., disruptive behaviors). The second meeting described procedures for recommending Triple P and reporting details of conversations (e.g., how endorsements were personalized for families).

Group leader engagement call

During this manualized, 20-minute call, the group leader elicited the mother’s child-focused goals and showed her how her goals could be addressed by Triple P. The group leader also asked about the biggest barrier to attendance and helped the mother problem-solve it. Then, the group leader helped the mother develop an action plan to handle common obstacles, such as scheduling conflicts, and how to set session reminders. Prior to the call, mothers were mailed materials to be used during the call (e.g., obstacles and solutions tip sheet), but the call was designed to be used with or without these materials because some parents might not have them available. A doctoral graduate student in psychology, a licensed clinical social worker, and a first grade teacher from the participating school (who did not have students in the study) were trained as group leaders and engagement callers. Group leaders participated in a 2-hour group training session led by the first author to learn the content and process of the engagement call protocol and role-play parts of the protocol with feedback.

Reminder calls

Group leaders made weekly reminder calls to parents in the experimental condition the night before or day of each session.

Non-engagement survey

To control for the personal contact received from teachers and group leaders in the experimental condition, mothers in the control condition participated in a 30-minute phone survey that assessed cultural values, parenting efficacy, opinions about parenting programs, participation barriers, program preferences, and reasons for not enrolling (if applicable). Data from these interviews were not used in the current study.

Engagement procedures

The research team mailed brochures and trained teachers and group leaders to implement engagement strategies. Teachers distributed testimonial flyers and conducted teacher endorsements. Group leaders conducted engagement calls. In both conditions, at the end of the engagement call or non-engagement survey, mothers were asked if they wanted to enroll in Triple P.

In both conditions mothers received $25 for participating in the call; completion rates were high for both--90% and 92%, respectively. Mothers did not receive monetary incentives for enrolling or attending Triple P sessions. Mothers in both conditions received the same amount of compensation (a total of $77 from the recruitment letter incentive, pre-test interview, and engagement or non-engagement call). Thus, compensation did not confound the experimental test of condition on engagement outcomes.

Parents who enrolled during the engagement call or non-engagement survey and those who returned the brochure’s enrollment form received a reminder letter about the date, time, and location of the program and light meal that would be served and a flyer about the free childcare.

The following best practice strategies were included in both conditions: delivering at a convenient location (i.e., school), meeting at convenient time(s) (i.e., evenings), matching parents and staff on language and ethnicity, providing free childcare and a light meal for parents and children before the sessions and handing out appointment calendars at session 1 (Dumka et al., 1997; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991). In cohort 2, one mother expressed a safety concern about walking home from sessions in the high-crime neighborhood; thus, taxi rides home from group sessions were offered to parents, regardless of condition. Three families (two in the experimental condition and one in the control condition) used this service.

Triple P implementation

The Triple P group level 4 program was implemented in the format prescribed by the developer and that has been shown to be effective (Sanders et al., 2014). Specifically, the intervention included eight weekly sessions with parents; children did not attend. Sessions 1 to 4 were 2-hour group sessions where parents learned Triple P skills. Sessions 5 to 7 were individual, 20-minute phone sessions with the group leader to hone skills. Session 8 was a final 2-hour group session to celebrate accomplishments and plan for the future. The program started about a week after parents received reminder letters. One Spanish-speaking and one English-speaking group per cohort (total of four groups) were delivered on week nights at the school. Spanish-speaking groups were larger (mean = 18 caregivers at session 1) than English-speaking groups (mean = 7 caregivers at session 1). We used standard Triple P procedures for maintaining high implementation quality. Specifically, group leaders attended a 3-day training conducted by a professional Triple P trainer and passed accreditation requirements at a 1-day follow-up evaluation session. Group leaders attended weekly peer supervision meetings during implementation, which were coordinated and led by the first author.

Measures

Dependent variables

Dependent variables included three engagement variables: enrollment, attendance, and program initiation.

Enrollment

This was a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not a parent signed up for Triple P at the end of the engagement call or non-engagement survey interview and/or by returning the enrollment form included with the brochure.

Attendance

This was the total number of sessions (0 to 8) attended by any caregiver in the family (including the phone sessions), as recorded by the group leader at each session.

Program initiation

This was a dichotomous variable created from the attendance data, 0 (no sessions attended), 1 (at least one caregiver attended at least one session).

Condition

Condition was a dichotomous variable 0 (control), 1 (experimental).

Demographic characteristics

Unless otherwise noted, mothers reported on demographic characteristics during the pre-test interview. Because engagement strategies were conducted primarily through mothers, we used mothers’ age, education and work status, rather than fathers’ or both. Mothers reported maternal age in years. Maternal education was a continuous variable representing years of education; college degrees were converted to years (e.g., Associate’s degree = 14, Bachelor’s = 16 etc…). To assess work status, mothers were asked how many hours per week, on average, they worked outside the home. Mother’s reported the target child’s age in years and child’s gender. To assess child’s birth order, mothers reported the ages of their oldest and youngest children, not including step-children. In combination with the target child’s age, a birth order variable was created: 1 (oldest/first born), 2 (middle), 3 (youngest/last born). Mothers reported family income from all sources, number of children under age 18 at home, and marital status. Two-parent was a dichotomous variable, 0 (never married, separated, divorced, widowed), 1 (married or living with a partner).

Potential Moderators

We examined child behavior problems, maternal acculturation level, and grade level as moderators of the effects of engagement condition.

Child behavior problems

The week prior to Triple P session 1 in the spring semester, teacher reports of child behavior problems were collected for all eligible target children whose mothers signed permission (98%). Teachers completed two subscales of the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation-Revised (TOCA-R), Version 10: conduct problems and concentration problems: 10-item Aggressive/Disruptive (e.g., breaks rules, fights, talks back) (α = .92 in this sample) and 11-item Concentration Problems (e.g., pays attention, stays on task) (α = .97 in this sample) (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). Items are rated on a 6-point scale from 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always). Teachers rated behavior over the previous three weeks. After reverse scoring positive behaviors, means were computed for each scale (see Table 1). Means and standard deviations (SDs) were similar to those reported for ethnically diverse samples of children in low-income, urban communities (e.g., Petras et al., 2004). Concurrent and predictive validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency have been established for these subscales (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 2010; Petras et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics by Condition

| Variable | Engagement Package (n = 61) | Control Group (n = 61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | |

| Maternal Age (years) | 32.9 (7.1)† | 20–53 | 30.6 (6.4) | 20–52 |

| Maternal Education (years) | 10.3 (2.6) | 5–16 | 9.89 (2.94) | 3–16 |

| Work Status (hours/week) | 16.0 (18.6) | 0–40 | 17.7 (20.2) | 0–80 |

| Child’s Age (years) | 7.0 (1.7) | 5–10 | 7.0 (1.7) | 5–10 |

| Child’s Birth Order | 2.1 (0.1)* | 1–3 | 1.7 (0.1) | 1–3 |

| Family Income | $22,497 ($11,079) | $2,580–$60,000 | $22,550 ($16,616) | $0–$78,000 |

| Number of Children | 3.5 (1.5) | 1–8 | 3.1 (1.5) | 1–8 |

| Conduct Problems | 2.0 (.8) | 1–4 | 1.9 (.8) | 1–4.4 |

| Concentration Problems | 2.8 (1.1) | 1–5 | 2.9 (1.2) | 1–5.6 |

| Anglo Orientation | 3.1 (1.4) | 1–5 | 3.1 (1.4) | 1–5 |

| Mexican Orientation | 3.8 (1.2) | 1–5 | 3.7 (1.3) | 1–5 |

| % (n’s) | % (n’s) | |||

|

| ||||

| % Female Child Gender | 52% (32 Female; 29 Male) | 59% (36 Female; 25 Male) | ||

| % Two-Parent Family | 67% (41 Two-Parent; 20 Single) | 67% (41 Two-Parent; 20 Single) | ||

| % Immigrant (Mother) | 61% (37 Immigrant; 24 U.S.) | 56% (34 Immigrant; 27 U.S.) | ||

| % English Speaking (Mother) | 49% (30 English; 31 Spanish) | 48% (29 English; 32 Spanish) | ||

| % 3rd Grade | 49% (30 3rd Grade; 31 K) | 49% (30 3rd Grade; 31 K) | ||

p < .10; two-tailed.

p < .05; two-tailed.

Maternal acculturation

The 12-item Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (Bauman, 2005) was used to assess Anglo and Mexican orientation: Anglo Oriented scale (e.g., “My friends are of Anglo origin”) (α = .94 in this sample) and Mexican Oriented scale (e.g., “I enjoy Spanish television”) (α = .95 in this sample). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (almost always). Reliability and validity of this measure have been established (Bauman, 2005; Cuevas, Sabina, & Bell, 2012). Means were computed for each scale (see Table 1). Means for the Anglo Oriented scale were similar to a national probability sample of Latina women; however, means for the Mexican Oriented scale were about ½ SD lower, perhaps because we blocked on language, resulting in fewer mothers interviewed in Spanish in our sample than the probability sample (53% vs. 72%) (Cuevas et al.). For immigrant status, mothers were asked if they were born in the United States. To assess primary language, mothers were asked if they spoke English, Spanish, or both; and if both, which they understood, spoke, and read better. If equally proficient, their interview language was used.

Grade level

The child’s grade level was identified on student rosters and confirmed by the child’s teacher; 3rd grade was a dichotomous variable, 0 (kindergarten), 1 (3rd grade).

Data Analytic Approach

T-test and chi-square analyses tested for baseline differences between conditions on study variables and other potential confounders, including maternal stress and perceived child behavior problems. As shown in Table 1, a significant difference occurred for the target child’s birth order and a marginally significant difference occurred for maternal age. On average, more target children were later-born in the experimental than control condition, and mothers tended to be older in the experimental than control group. To control for these differences, we included birth order and maternal age as covariates in all analyses examining the effects of condition.

Participants were clustered in classrooms; thus, intraclass correlations were examined for all study variables. Intraclass correlations were negligible for the dependent variables (less than .02) but ranged from 0 for mother’s work status to .46 for primary language (because the school had self-contained classes for English language learners). Given many of the intraclass correlations were non-ignorable (i.e., greater than .05), all analyses adjusted for cluster effects.

To test whether or not sociocultural group moderated the effects of condition, we used a person-oriented approach, latent class analysis, to define sociocultural groups. Latent class analysis provides an effective method for identifying subgroups within a population; which allows researchers to examine how discrete subgroups, who are characterized by multiple contextual variables, respond to an intervention (Lanza & Rhoades, 2013). The following variables were included: acculturation indicators (Anglo orientation, Mexican orientation, immigrant status, primary language) and demographic characteristics (family income, maternal education, work status, and family structure). Because the sample was almost exclusively Mexican American (3%; n = 3 non-Hispanic White), race and ethnicity were not included. Results of the latent class analysis indicated that the two-class solution was significantly better than the one-class solution (1- vs. 2-class model: Sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion = 5573.91 vs. 5093.23, Loglikelihood value = −2776.28 vs. −2528.55, Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test = 495.453, p < .001). Although the three-class solution was marginally significantly better than the two-class solution, p < .08, the third class had only 13 participants, which would not be sufficient for conducting moderation analyses. Therefore, the two-class solution was selected. The sociocultural profiles for the two classes are shown in Table 2. Mothers in Class 1 were more highly acculturated, had higher income and education, worked more hours, and were more likely to be single mothers than mothers in Class 2.

Table 2.

Sociocultural Profiles by Latent Class

| Variable | Class 1 (n = 60) | Class 2 (n = 62) |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Anglo Orientation | 4.4 (.5) | 1.8 (.7) |

| Mexican Orientation | 2.9 (1.2) | 4.7 (.5) |

| Family Income | $28,336 ($16,328) | $17,098 ($8,796) |

| Maternal Education | 11.6 (2.2) | 8.7 (2.6) |

| Work Status (hours/week) | 23.3 (20.4) | 10.5 (16.2) |

| % (n’s) | % (n’s) | |

|

| ||

| % Immigrant (Mother) | 17% (10 Immigrant; 50 Born in U.S.) | 98% (61 Immigrant;1 Born in U.S.) |

| % English Primary Language (Mother) | 98% (59 English; 1 Spanish) | 0% (0 English; 62 Spanish) |

| % Two-Parent | 52% (31 Two-Parent; 29 Single Mother) | 82% (51 Two-Parent; 11 Single Mother) |

We used Mplus (Version 7, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) for all analyses. Intent-to- treat analyses were used. Specifically, all participants who completed the pre-test interview were randomized to the experimental or control condition and were included in analyses even if they did not complete the engagement call or non-engagement survey interview. Missing data on covariates were handled using full information maximum likelihood (Arbuckle, 1996; Schafer & Graham, 2002). There were no missing data for dependent variables, because all participants randomized to condition had complete data on enrollment, initiation, and attendance, regardless of whether or not they completed the engagement call or non-engagement survey interview. An alpha of .05 based on the one-tail test was used for testing significance of a priori hypotheses.

Logistic regressions were used to test main effects of condition, and moderation effects of sociocultural group and behavior problem variables, on enrollment and initiation. Continuous moderators were centered (i.e., mean = 0) to facilitate interpretability of the results and reduce the correlations between a multiplicative term and its components (Aiken & West, 1991). We used negative binomial regression analyses to test effects on attendance (i.e., number of sessions attended; 0–8) to account for the large number of zero values of those who never attended and the overdispersed distribution (see Hilbe, 2007; Long & Freese, 2006). Interactive effects were examined first. If interactions were significant, tests of simple effects were conducted, examining differences across levels of the moderator. For the continuous moderator, the differences between the conditions at ± 1 SD from the mean on the moderator were examined. If there were no significant interactions, models were re-run without interaction terms.

Results

Enrollment was high in the experimental (74%) and control (69%) conditions and did not differ significantly. Among those who enrolled 64% initiated in the experimental condition, compared to 36% in the control condition. Among those who initiated, the average number of sessions attended was 5 out of 8 (63%) for both conditions. Although significantly more families initiated in the experimental condition than the control condition, 48% (n = 29) versus 25% (n = 15); OR = 2.49, t = 1.97, p < .05, 95% CI [1.01, 6.16]; as described below, the effect of condition on initiation was moderated by child concentration problems.

Moderating Effects of Baseline Child Behavior Problems

Enrollment

There were no significant interactions between condition and child conduct or concentration problems on enrollment.

Initiation

As shown in Table 3, parents of children with high concentration problems were more likely to initiate in the experimental than the control condition. The top of Figure 3 shows initiation rates for each condition at high and low levels of concentration problems. The test of simple effects showed that the difference between conditions was significant at 1 SD above the mean on child concentration problems; OR = 8.98, t = 3.42, p < .001, 95% CI [2.55, 31.57], but was not significant at 1 SD below the mean.

Table 3.

Effects of Engagement Condition and Baseline Moderators on Program Initiation and Attendance

| Predictor | Initiation | Attendance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | 95% CI | b (SE) | 95% CI | |

| 1. Condition | .96 (.50)* | [.02, 1.94] | .34 (.37) | [−.39, 1.07] |

| Concentration Problems | −.52 (.24)* | [−.99, −.05] | −.28(.21) | [−.69, .13] |

| Condition x Concentration Problems | 1.10 (.37)** | [.37, 1.83] | .84 (.29)** | [.27, 1.41] |

| 2. Condition | .94 (.45)* | [.06, 1.82] | .57 (.36)† | [−.14, 1.28] |

| Conduct Problems | −.17 (.45) | [−1.05, .71] | −.99(.41)** | [−1.79, −.19] |

| Condition x Conduct Problems | .57 (.65) | [−.70, 1.84] | 1.23 (.50)** | [.25, 2.21] |

| 3. Condition | 1.44 (.51)** | [.42, 2.46] | 1.30 (.52)** | [.28, 2.32] |

| Sociocultural Class | 1.04 (.69) | [−.31, 2.39] | 1.42 (.58)** | [.28, 2.57] |

| Condition x Sociocultural Group | −.86 (.99) | [−2.80, 1.08] | −1.31 (.70)* | [−2.68, .06] |

Note. CI = confidence interval. For initiation, regression coefficients were obtained from logistic regressions; for attendance, coefficients were obtained from negative binomial regression analyses. All analyses included child birth order and maternal age as covariates.

p <.01; one-tailed..

p <.05.

p <.10.

Figure 3.

Interactive effects of condition on program initiation and attendance by baseline concentration problems and sociocultural group.

Attendance

To examine condition effects on attendance, negative binomial regression analyses were conducted with all families, including those who never initiated. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 4, there were significant interactions between condition and conduct and concentration problems. Attendance was significantly higher in the experimental condition compared to the control condition for parents of children exhibiting high conduct or concentration problems: 1 SD above the mean on conduct problems; b = 1.54 (SE = .52), t = 2.94, p < .01, 95% CI [.51, 2.56], d = .54 and 1 SD above the mean on concentration problems; b = 1.31 (SE = .49), t = 2.67, p < .01, 95% CI [.35, 2.26], d = .49. Among parents of children with low behavior problems (1 SD or more below the mean), there were no significant differences between the experimental and control conditions.

Figure 4.

Interactive effects of condition on program attendance by child conduct and concentration problems.

Effects of Sociocultural Group

Overall, highly acculturated mothers (Class 1) were less likely to engage than low acculturated mothers (Class 2): 58% vs. 84% enrolled, χ2 (1) = 9.72, p < .01; 28% vs. 44% initiated, χ2 (1) = 3.06, p = .08; attendance: M (SD) = 1.3 (2.52) vs. 2.2 (3.08), t = −1.65, p < .05, 95% CI [0.7, 2.0 vs. 1.4, 3.0]. Also, children of highly acculturated, Mexican American mothers had higher behavior problems than those of low acculturated mothers: conduct problems, M (SD) = 2.2 (.88) vs. 1.7 (.66), t = 3.22, p < .001, 95% CI [1.9, 2.4 vs. 1.5, 1.9]; concentration problems, M (SD) = 3.2 (1.19) vs. 2.6 (1.07), t = 2.78, p < .01, 95% CI [2.8, 3.5 vs. 2.3, 2.9].

There were no significant interactions between condition and sociocultural group on enrollment or initiation. However, as shown in Table 3 and the bottom of Figure 3, sociocultural group moderated the effect of condition on attendance. Simple effect tests showed that attendance was significantly higher in the experimental versus control condition for the highly acculturated group; b = 1.30 (SE = .52), t = 2.50, p < .01, 95% CI [.28, 2.57], d = .66. There were no significant differences between the experimental and control conditions for the low acculturated group.

Grade Level as a Moderator

There were no significant differences in enrollment, initiation or attendance between parents of kindergarten versus third grade students, and grade level did not moderate the effects of condition on any of these dependent variables.

Discussion

In this study, we applied a systematic, theory-based approach (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Sandler et al., 1997) to develop and test the efficacy of brief, motivationally-based strategies for engaging parents into parenting interventions that prevent child behavior problems. Given the low rates of engagement that have been observed when programs are implemented under real-world conditions, identifying effective engagement strategies is critical for evidence-based parenting programs to produce significant public health benefits. The engagement package increased initiation and attendance for parents whose children had higher levels of behavior problems, as well as for highly acculturated, Mexican American parents who have been especially difficult to engage. Effect sizes were in the medium-large range.

To our knowledge, this was the first experimental study to demonstrate that brief motivational enhancement techniques increased initiation and attendance in a preventive parenting program. Effect sizes were comparable to those found for brief motivational strategies that have been experimentally tested in the child mental health treatment literature (Coatsworth et al., 2001; McKay et al., 1998; Nock & Kazdin, 2005) and to those reported by Shephard and colleagues (2012) for their two-session, in-home motivational interviewing intervention for engaging into a preventive parenting program. We achieved results similar to those of Shephard and colleagues using a much less resource-intensive package of strategies, which is important because intensive strategies may not be feasible and sustainable for schools and other community agencies to implement under real-world conditions.

It is especially encouraging that the engagement package was effective for parents of children with high levels of teacher-reported behavior problems. Because preventive parenting programs appear to be most effective for children experiencing elevated behavior problems (e.g., Reid et al., 2004; Gonzales et al., 2013; Wolchik et al., 2000), our findings suggest the motivational engagement package increased attendance for families who can most benefit from preventive parenting interventions, which has significant public health implications.

Acculturation

Consistent with prior research (Carpentier et al., 2007; Dumka et al., 1997), we found a large disparity in attendance between high- and low-acculturated parents in the control condition. The experimental engagement package more than tripled the attendance of highly acculturated parents in the control condition. This finding is encouraging because children of highly acculturated mothers had higher behavior problems than children of low acculturated mothers. Thus, the engagement package increased attendance for the subgroup of Mexican American parents whose children are most at risk for future behavior problems (Gonzales et al., 2014).

Enrollment and Initiation

Unexpectedly, enrollment did not significantly differ between the control and experimental groups. Enrollment rates were moderately high in both conditions, 69% vs. 74%, respectively. However, impacting initiation and attendance may be more important than enrollment, particularly in this study in which social desirability bias may have influenced enrollment because all mothers were asked about enrollment during the non-engagement survey interview (control group) or group leader engagement call (experimental group). In our study, only 36% of control group parents who enrolled attended at least one session, compared to 64% of those in the experimental group who enrolled. This suggests that the engagement package reduced the intention-behavior gap (Baker et al., 2011; Webb & Sheeran, 2006). The theory-based, motivational engagement strategies (parent testimonial flyer, teacher endorsement, and group leader engagement call) may have impacted factors related to whether intentions become actions, such as problem solving barriers, planning logistics, and creating cues to action (i.e., setting reminders). In future work, we plan to examine mediators of engagement package effects to understand the processes through which it increases initiation and attendance.

Grade Level

Contrary to expectations, we found no evidence that parents of kindergarten students would be more likely to engage than those of third grade students, and grade level did not moderate the effects of condition on enrollment, initiation, or attendance. This suggests that the engagement package was equally effective for parents of children making the transition to elementary school as it was for parents of children who had already transitioned. This has implications for future dissemination, suggesting that the package may have broad applicability with respect to the timing of engagement strategies.

Implications

The engagement package was most effective for families who benefit the most from evidence-based parenting interventions. Thus, this package has the potential to substantially increase the reach and public health impact of these interventions. Its use could maximize the impact of universal preventive parenting interventions by engaging a higher proportion of families who could most benefit. These engagement strategies are a viable alternative to the indicated prevention approach of offering an intervention only to parents of children already exhibiting high behavior problems, an approach that risks stigmatizing those selected.

Limitations and Future Directions

The study had several limitations. We did not assess implementation fidelity or quality of the engagement strategies. Further, the sample was small and composed almost entirely of English- and Spanish-speaking Mexican American parents living in low-income conditions. This is an important population to study, given that highly acculturated, Mexican American children who live in poverty are at risk for a host of problems (Alegría et al., 2008; Gonzales et al., 2014). However, results may not generalize to other cultural groups. Studying whether this package yields similar results with other populations is an important question for future research. Also, findings were based on a group of parents willing to participate in the research project, and parents were paid for participating in research and engagement call or non-engagement survey interviews. Effect sizes may differ when examined under real-world delivery conditions. The group leaders were not blind to condition, and they led Triple P groups composed of parents from both conditions. Thus, group leaders could have differentially influenced parental attendance across conditions, although we did not have any evidence that this occurred.

Finally, the experimental components differed regarding the resources required to implement them, and our design did not allow us to identify the active ingredients or compare the cost effectiveness of the strategies. The testimonial flyer was the easiest to implement; whereas, the engagement call was the most time-consuming as well as the most challenging, because it required group leaders to learn a manualized protocol. The teacher endorsement required some training, but was easier to implement than engagement calls because it was not scripted and could be integrated into typical parent-teacher interactions (e.g., conferences). Thus, future research should identify the active ingredients of the engagement package and compare the cost effectiveness of the strategies in a larger, more culturally diverse sample to streamline it and prepare for dissemination.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed and tested a theory-based engagement package to increase engagement in evidence-based parenting programs that prevent child behavior problems. The package was developed using strategies identified in the literature and refined using input from parents and teachers from a community where the majority of residents were of Mexican descent and experiencing poverty. Compared to a brochure plus non-engagement interview condition, the package increased initiation and/or attendance for parents of children with high teacher-reported concentration or conduct problems and for highly acculturated, Mexican American parents. This engagement package could help address the problem of low initiation and attendance, which has been a critical barrier to the adoption, implementation, sustainability and public health impact of evidence-based preventive parenting programs. Further, the engagement package could be adapted for any parenting program from the prenatal period to adolescence and used across multiple intervention levels (i.e., universal, selective, indicated) and settings (e.g., schools, pediatric offices, courts) to increase the public health impact of evidence-based parenting interventions.1

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance.

This study suggests that an engagement package increased parenting program attendance among familes who could most benefit. The package could help optimize the public health impact of evidence-based parenting programs by increasing attendance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a career development award granted to the first author from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), K01 MH074045. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

We thank the principals, staff, and parents at Sutton Elementary School for partnering with us in this research. We also thank consultants who provided guidance and training to the first author as part of the career development award supporting this study; including Mary McKay, Ph.D., for training in engagement interviewing; Paul Karoly, Ph.D., for helping to develop the conceptual model of engagement; and Mark Roosa, Ph.D., for guidance on ethical issues. We thank students for their assistance, in particular Veronica Bordes, Ph.D., and Angela Zamora, Ph.D., for helping to coordinate data collection and the school partnership; and Alexandra Ingram for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Manuals and materials for this engagement package can be obtained by contacting the first author.

References

- Abraham C, Sheeran P. Implications of goal theories for the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social. 2003;22:264–280. doi: 10.1007/s12144-003-1021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, … Meng XL. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced Structural Equation Modeling. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- Axford N, Lehtonen M, Kaoukji D, Tobin K, Berry V. Engaging parents in parenting programs: Lessons from research and practice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:2061–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Arnold DH, Meagher S. Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science. 2011;12(2):126–138. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S. The reliability and validity of the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans—II for Children and Adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27(4):426–441. doi: 10.1177/0739986305281423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N. Predicting negative life outcomes from early aggressive–disruptive behavior trajectories: Gender differences in maladaptation across life domains. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(8):953–966. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier FD, Mauricio A, Gonzales N, Millsap R, Meza C, Dumka L, … Genalo M. Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28(6):521–546. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. Influence: Science and Practice. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Santisteban DA, McBride CK, Szapocznik J. Brief strategic family therapy versus community control: Engagement, retention, and an exploration of the moderating role of adolescent symptom severity. Family Process. 2001;40:313–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4030100313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso P, Fang X, Begle A, Dumas J. Predictors of engagement in a parenting intervention designed to prevent child maltreatment. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;11(3):235–241. Retrieved from http://westjem.com. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas C, Sabina A, Bell K. The effect of acculturation and immigration on the victimization and psychological distress link in a national sample of Latino women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(8):1428–1456. doi: 10.1177/0886260511425797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone P, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit G, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74(Serial No 294):1–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas J, Begle A, French B, Pearl A. Effects of monetary incentives on engagement in the PACE parenting program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(3):302–313. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Garza CA, Roosa MW, Stoerzinger HD. Recruitment and retention of high-risk families into a preventive parent training intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1997;18(1):25–39. doi: 10.1023/A:1024626105091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, Reeves M, Gutierrez S, McLaughlin P. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: The Resources for Health study. Health Education Research. 2007;22(3):361–371. doi: 10.1093/her/cy1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan A, Hanson K, Hawkins JD, Arthur M. Translational research in action: Implementation of the communities that care prevention system in 12 communities. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(7):809–829. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Boden J, Horwood L. Situational and generalised conduct problems and later life outcomes: Evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1084–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer P, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;38:69–119. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales N, Dumka L, Millsap R, Gottschall A, McClain D, Wong J, … Kim S. Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0026063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales N, Jensen M, Montano Z, Wynne H. The cultural adaptation and mental health of Mexican American adolescents. In: Caldera Y, Lindsey E, editors. Handbook of Mexican American Children and Families: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Oxford, UK: Routledge; 2014. pp. 182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Johnson T, Ridge A, Garvey C, Julion W, Treysman A, Breitenstein S, Fogg L. Cost-effectiveness of childcare discounts on parent participation in preventive parent training in low-income communities. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2011;32:283–298. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra N, Huesmann L, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development. 2003;74(5):1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N, Bertram H, Kuschel A, Hahlweg K. Parent recruitment and retention in a universal prevention program for child behavior and emotional problems: Barriers to research and program participation. Prevention Science. 2005;6(4):275–286. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative binomial regression. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM. Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(5):629–645. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza S, Rhoades B. Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science. 2013;14:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. 2. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Vol. 23. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R, Conner M, Taylor N, Lawton R. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review. 2011;5(2):97–144. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2010.521684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health & Social Work. 1998;23(1) doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. In: O’Connell Mary Ellen, Boat Thomas, Warner Kenneth E., editors. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Washington, D.C: National Academics Press; 2009. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C, Holmberg EB. Parent beliefs about treatment credibility and effectiveness: Assessment and relation to subsequent treatment participation. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(1):27–38. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Parent expectancies for child therapy: Assessment and relation to participation in treatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2001;10:155–180. doi: 10.1023/A:1016699424731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(5):872–879. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program using hierarchical linear modeling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11(3):114–144. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras H, Chilcoat HD, Leaf PJ, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG. Utility of TOCA-R scores during the elementary school years in identifying later violence among adolescent males. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(1):88–96. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C, Baydar N. Halting the development of conduct problems in Head Start children: The effects of parent training. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):279–291. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy MC, Orpinas P, Davis M. Successful recruitment and retention of Latino study participants. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;13(6):779–787. doi: 10.1177/1524839911405842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M, Kirby J, Tellegen C, Day J. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:337–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Schoenfelder E, Wolchik S, MacKinnon D. Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:299–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, MacKinnon DP, Ayers TS, Roosa MW. Developing linkages between theory and intervention in stress and coping processes. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children's coping: Linking theory and intervention. NY: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME, Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2011;32(2):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Poduska J, Kellam S. Modeling growth in boys' aggressive behavior across elementary school: Links to later criminal involvement, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(6):1020–1035. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard S, Armstrong L, Silver R, Berger R, Seifer R. Embedding the family check-up and evidence-based parenting programmes in Head Start to increase parent engagement and reduce conduct problems in young children. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2012;5(3):194–207. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2012.707432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Clair S, Greenberg M, Redmond C, Shin C. Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: Maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):137–145. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Modeling factors influencing enrollment in family-focused preventive intervention research. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):213–225. doi: 10.1023/A:1026551229118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Fujino D, Hu L, Takeuchi D, Zane N. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(4):533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(2):249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington L, White KM, Liossis P. Beliefs underlying intentions to participate in group parenting education. Advances in Mental Health. 2006;5(3):275–283. doi: 10.5172/jamh.5.3.275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam S, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19(4):585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Wellington L. Predicting participation in group parenting education in an Australian sample: The role of attitudes, norms, and control factors. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(2):173–189. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0167-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Bonds D, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Braver SL. Predictors of enrollment and retention in a preventive parenting intervention for divorced families. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(2):151–172. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Shaw DS. Impact of neighborhood disadvantage on overt behavior problems during early childhood. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33(3):207–219. doi: 10.1002/ab.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik S, West S, Sandler I, Tein J, Coatsworth J, Lengua L, … Griffin W. An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:843–856. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirkel S, Cantor N. Personal construal of life tasks: Those who struggle for independence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:172–185. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.