Abstract

Background

Rhinovirus (RV) infection in asthma induces varying degrees of airway inflammation (e.g., neutrophils), but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Objective

The major goal was to determine the role of genetic variation (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) of Toll-interacting protein (Tollip) in airway epithelial responses to RV in a type 2 cytokine milieu.

Methods

DNA from blood of asthmatic and normal subjects was genotyped for Tollip SNP rs5743899 AA, AG and GG genotypes. Human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells from donors without lung disease were cultured to determine pro-inflammatory and anti-viral responses to IL-13 and RV16. Tollip knockout and wild-type mice were challenged with house dust mite (HDM) and infected with RV1B to determine lung inflammation and anti-viral response.

Results

Asthmatic subjects carrying the AG or GG genotype (AG/GG) compared with the AA genotype demonstrated greater airflow limitation. HTBE cells with AG/GG expressed less Tollip. Upon IL-13 and RV16 treatment, cells with AG/GG (versus AA) produced more IL-8 and expressed less anti-viral genes, which was coupled with increased NF-κB activity and decreased expression of LC3, a hallmark of the autophagic pathway. Tollip co-localized and interacted with LC3. Inhibition of autophagy decreased anti-viral genes in IL-13 and RV16 treated cells. Upon HDM and RV1B, Tollip knockout (versus wild-type) mice demonstrated higher levels of lung neutrophilic inflammation and viral load, but lower levels of anti-viral gene expression.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance

Our data suggest that Tollip SNP rs5743899 may predict varying airway response to RV infection in asthma.

Keywords: Airway epithelial cells, Autophagy, Inflammation, Rhinovirus, Tollip

Introduction

Rhinovirus (RV) infection is a major cause of asthma exacerbations [1, 2]. RV primarily infects airway epithelial cells. In a normal setting, RV-induced host pro-inflammatory (e.g., IL-8 production) and anti-viral (e.g., expression of IFN-λ1) responses are necessary to contain the viral infection [3, 4]. IFN-λ1 is critical to host defense against RV infection [5, 6]. Impaired IFN-λ1 expression has been reported in cultured asthmatic airway epithelial cells [5, 6]. While the appropriate pro-inflammatory response such as neutrophil recruitment/activation is beneficial during the viral infection, excessive airway inflammation may be responsible for asthma exacerbations [7].

During natural RV infection, asthmatic subjects demonstrated increased airway neutrophilic, but not eosinophilic inflammation [8]. There was large variation in the pro-inflammatory response among RV-infected asthmatic subjects, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. It is likely that genetic variation (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) of innate defense mechanisms might in part explain the variation of airway response to RV infection. Various innate immunity pathways including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and autophagy are involved in RV infection [9-11]. Toll-interacting protein (Tollip), a 30 kDa adaptor protein [12], is recognized as a negative regulator of TLR signaling [13-15]. Recent studies suggest that Tollip is involved in autophagy [16-19]. For example, human Tollip is required for the proper clearance of Huntington's disease-linked polyQ proteins through the ubiquitin-dependent autophagy [19]. As autophagy participates in the anti-RV response in a normal setting [10, 20], Tollip may also serve as a novel mechanism to modulate host responses to RV infection in a type 2 cytokine milieu (e.g., IL-13), a major feature of airway allergic inflammation.

Several Tollip SNPs have been implicated in sepsis [21], tuberculosis [13] and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [22], but the function of Tollip SNPs in airways disease such as asthma is unclear. We hypothesized that Tollip SNPs (e.g., rs5743899) and associated changes Tollip expression levels contribute to varying degrees of human airway epithelial responses to RV infection in a type 2 cytokine (e.g., IL-13) milieu. To test our hypothesis, we used a cell culture model of IL-13 stimulated primary human airway epithelial cells to mimic the type 2 cytokine high environment seen in atopic asthmatic airways [23]. Additionally, a Tollip deficient mouse model of house dust mite challenge was utilized to further determine the in vivo function of Tollip in lung RV infection and inflammation.

Methods

Collection of human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells

We obtained de-identified donor lungs through the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (Edison, NJ) and the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA). These lungs were not suitable for transplantation and donated for medical research. The donors we chose for the current study did not have history of lung disease, and were non-smokers or ex-smokers who had quitted smoking for at least 10 years. The causes of death were related to trauma or cerebral vascular accident. Histopathology was performed to confirm no sign of lung inflammatory lesion, infection or tumor. To isolate HTBE cells, tracheal and main bronchial tissue was digested with 0.1% protease overnight at 4°C, and processed as previously described [24]. Cell collection was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at National Jewish Health.

Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotyping

Genomic DNA from blood of asthmatic and normal subjects recruited at University of Arizona was extracted for Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotyping. The subjects with asthma fulfilled criteria for asthma [25], exhibiting a provocative concentration of methacholine resulting in a 20% fall in FEV1 (PC20) of 8 mg/ml and reversibility, as demonstrated by at least a 12% and 200 ml increase in FEV1 or FVC with inhaled albuterol. Healthy (normal) subjects had a methacholine PC20 greater than 16 mg/ml, no evidence of airflow obstruction, and no history of pulmonary disease. DNA of HTBE from donors’ lungs collected at National Jewish Health was also extracted for Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotyping. Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotyping was performed by using a PCR assay from Applied Biosystems (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA). Positive control DNA containing Tollip SNP rs5743899 major homozygote AA, heterozygote AG or minor homozygote GG was obtained from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). HTBE cells from 83 donors were genotyped as rs5743899 AA (n = 48, 57.8%), AG (n = 29, 34.9%) and GG (n = 6, 7.3%). The characteristics of human donors (n = 17) included in our cell culture study were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Human donors with different Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotypes

| Tollip rs5743899 | N | Age (yrs) | Gender (M/F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 7 | 61.3±3.8 | 4/3 |

| AG | 6 | 52.1±7.3 | 3/3 |

| GG | 4 | 50.3±10.0 | 3/1 |

Preparation of RV16 and RV1B

RV16 and RV1B were propagated in H1-HeLa cells and purified as described previously [10]. 50% tissue culture infective dose per ml (TCID50/ml) or plaque-forming unit (PFU) was used to indicate the viral titer.

HTBE cell culture and treatments

HTBE cells at passage 2 were seeded into 12-well plates at 1×105 cells/well in bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Recombinant human IL-13 (10 ng/ml, dissolved in PBS containing 10 ng/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA]) or BSA (control, 10 ng/ml) was added to cells. After 24 hours, cells were incubated with RV16 (4×104 TCID50/well) for 2 hours at 37°C, and then washed with medium. Twenty-four hours later, cell supernatants and lysates were collected for ELISA, RNA extraction and Western blot. To determine the role of autophagy and NF-κB activation in RV infection, bafilomycin A1 (100 nM), helenalin (5 μM, dissolved) in 0.1% DMSO or 0.1% DMSO (control) was added at the time of virus removal. Previous studies [26-28] demonstrated 24-hour post RV infection as the optimal time point to measure various mediators. In a pilot study, we infected HTBE cells with RV16 for 4, 24 and 48 hours, and found that IL-8 mRNA and protein induction peaked at 4 and 24 hr post RV16 infection, respectively. RV16 level was the highest at 24 hr post infection (data not shown).

Quantitative real-time PCR

TaqMan gene expression assays Applied Biosystems (Life Technologies, Foster City CA) were used to measure mRNA of human Mx1, IFN-λ1, Tollip and GAPDH, and mouse Mx1, MUC5AC, IL-13 and 18S rRNA. Target gene expression was normalized to GAPDH and 18S rRNA for human and mouse samples, respectively. The comparative threshold cycle method was used to determine the relative gene expression level [29].

Western blot

Equal amount of cell lysate proteins was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and probed with rat anti-human Tollip (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY), mouse anti-p-IκBα, rabbit anti-total IκBα, mouse anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or rabbit anti-LC3 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Densitometry was performed to quantify proteins.

Immunofluorescent staining to co-localize LC3 and Tollip

HTBE cells transfected with a plasmid containing the pBABE-puro mCherry-EGFP-LC3 cDNA construct were embedded in 1% low-melting-temperature agarose, fixed in 10% formalin, processed for embedding in paraffin and cut into sections at 4 μm thickness. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed to co-localize GFP (indication of LC3) and Tollip.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Co-IP was performed [30] to determine the interaction of Tollip and LC3. Briefly, cultured HTBE cells were incubated with ice-cold lysis buffer, sonicated and centrifuged. The supernatant was pre-cleared with protein A-agarose beads and incubated with anti-human LC3 antibody or control IgG. Immunoprecipitates were collected with protein A-agarose beads and dissolved in 1xLDS sample buffer. Western blot for Tollip and LC3 was then performed.

Tollip small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

HTBE cells in 12-well plates were transfected with human Tollip siRNA or control siRNA as per manufacturer's instruction (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Cells were then treated with IL-13 (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours and then infected with RV16 (4×104 TCID50/well) for another 24 hours. Cell supernatants and lysates were collected.

Mouse model of house dust mite (HDM) challenge and RV1B infection

All the animal procedures were approved by National Jewish Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Tollip knockout (KO) mice on the C57BL/6 background were bred at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were intranasally sensitized with 100 μg house dust mite (HDM) extract (Greer Laboratory, Lenoir, NC) in 50 μl saline on day 0 and day 7. On days 14, 15 and 16, mice were intranasally challenged with HDM or with saline as a control. On day 18, mice were intranasally inoculated with RV1B (1×107 PFU) in 50 μl PBS or with PBS as a control. On day 21, mice were sacrificed and the lungs were lavaged with 1 ml saline to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. BAL cell cytospin slides were stained with a Diff-Quick stain kit (IMEB, San Marcos, CA) for cell differential counts. Left lungs were used for RNA extraction to detect RV1B RNA by real-time PCR [28]. We chose day 3 post RV1B infection as the end time point because: (1) our research goal was to determine if Tollip affects both neutrophilic and eosinophilc inflammation during HDM challenges and rhinovirus infection; (2) in HDM-challenged mice, lung eosinophils increased from day 2 to day 7 after rhinovirus infection; and (3) lung neutrophilic inflammation can last for up to 4 days post RV1B infection.

Mouse lung histological analysis

The apical lobe of the mouse right lung was fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut at 5 μm thickness for histological analysis. H&E-stained lung sections were evaluated in a blinded fashion under the light microscope using a histopathologic inflammatory scoring system as we described [31]. A final score per mouse on a scale of 0 to 26 (least to most severe) was obtained based on an assessment of the quantity and quality of peribronchiolar and peribronchial inflammatory infiltrates, luminal exudates, perivascular infiltrates, and parenchymal pneumonia.

ELISA

Human IL-8 and eotaxin-3, and mouse KC were measured by using the ELISA kits from R&D System (Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical analysis

For normally distributed data, t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare groups. If the overall ANOVA F-test was significant, pairwise comparisons were made. When the data were not normally distributed, Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used instead. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Two way ANOVA was used to test the association between Tollip genotype and lung function measures (e.g., FEV1 % predicted, FVC% predicted, FEV1/FVC ratio) for asthmatic and normal subjects. For subjects with asthma, multiple linear regression was used to test the association between Tollip genotype and lung function while controlling for age, gender, asthma severity and airway hyper-responsiveness as measured by methacholine PC20.

Results

Asthmatic subjects with the Tollip SNP rs5743899 AG or GG genotype demonstrated reduced lung function

As shown in Table 2, asthmatic subjects included in this study were of mild to moderate severity. The frequency of the rs5743899 AG genotype is higher in asthmatics (49.0%) than normal subjects (36.4%), but this was not statistically different due to the small sample size. As the frequency of the GG genotype is low (<10%) in both asthmatics and normal subjects, pulmonary function in subjects carrying the AG or GG genotype (AG/GG) versus the AA genotype was compared. In univariate analyses, asthmatics with AG/GG had a significantly lower FEV1/FVC ratio than those with the AA genotype (Figure 1), indicating greater airflow limitation in asthmatic subjects carrying the G allele. In a multivariate analysis controlling for age, gender, asthma severity and airway hyper-responsiveness, asthmatic subjects with AG/GG were estimated to have 4.4 percentage points lower FEV1/FVC than asthmatics with the AA genotype (95% confidence interval: 9.0 lower to 0.2 higher, p=0.059). There were no significant differences in FEV1% predicted, FVC%, PC20, or blood neutrophils (%) or eosinophils (%) between genotypes in the univariate or multivariate analyses.

Table 2.

Characteristics of asthma and normal subjects with different Tollip SNP rs5743899 genotypes

| Tollip rs5743899 | AA | AG | GG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma/Normal | Asthma | Normal | Asthma | Normal | Asthma | Normal |

| N (%) | 23 (45.1%) | 30 (54.5%) | 25 (49.0%) | 20 (36.4%) | 3 (5.9%) | 5 (9.1%) |

| Males | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Females | 15 | 24 | 17 | 12 | 2 | 3 |

| White | 17 | 22 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 5 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 3 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| FEV1 (%) | 89.1 ± 2.7 | 100.3 ± 2.0 | 87.0 ± 2.9 | 100.6 ± 3.5 | 87.3 ± 6.6 | 98.6 ± 4.8 |

| FVC (%) | 97.6 ± 2.7 | 102.7 ± 2.4 | 98.7 ± 2.7 | 106.6 ± 4.2 | 99.7 ± 0.7 | 100.0 ± 3.0 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 76.7 ± 1.4 | 84.1 ± 1.1 | 71.6 ± 1.6 | 80.3 ± 1.9 | 76.7 ± 6.3 | 82.0 ± 3.3 |

| PC20 (mg/ml) | 2.0 ± 0.7 | > 16 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | > 16 | 2.3 ± 2.0 | > 16 |

| Asthma severity | Mild (n =18) Moderate (n = 5) | N/A | Mild (n =22) Moderate (n = 3) | N/A | Mild (n = 3) | N/A |

| Exacerbations per year | 1.0 ± 0.0 | N/A | 1.0 ± 0.0 | N/A | 2.0 ± 0.3 | N/A |

| Atopy (% positive) | 89 | 41 | 83 | 41 | 67 | 80 |

| Peripheral Eosinophils (%) | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | N/A |

| Peripheral Neutrophils (%) | 58.7 ± 1.8 | 57.9 ± 6.7 | 45.6 ± 0.0 | 48.1 ± 1.9 | 55.8 ± 2.7 | N/A |

| Medications | ||||||

| Albuterol alone (%) | 100 | N/A | 100 | N/A | 100 | N/A |

| ICS alone (%) | 17 | N/A | 0 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| ICS/LABA (%) | 21 | N/A | 20 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| Leukotriene antagonist (%) | 4 | N/A | 8 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| Anti-histamine (%) | 48 | 3.3 | 20 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

Figure 1. Asthmatic subjects with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype had a lower FEV1/FVC ratio than those with the AA genotype.

N = 51 for asthma patients (AA = 23; AG/GG = 28), and n = 55 for normal subjects (AA = 30; AG/GG = 25).

Increased pro-inflammatory response in IL-13 and RV16 treated HTBE cells with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype

We sought to determine whether airway epithelial cells expressing AG/GG produce higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines following IL-13 and RV16 treatment. We measured IL-8 and eotaxin-3 as they are involved in neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation, respectively [32]. As airway epithelial cells expressing the AG and GG genotypes demonstrated similar pro-inflammatory response to RV16 infection, we combined the data from cells expressing AG/GG in order demonstrate the G allele effect of rs5743899. As shown in Figure 2A, at the baseline or with IL-13 alone, cells with AG/GG trended to have higher levels of IL-8 than cells with the AA genotype. However, when treated with both IL-13 and RV16, cells with AG/GG had significantly higher levels of IL-8 than the AA genotype. Eotaxin-3 protein was not detectable in cells without IL-13 treatment. As expected, IL-13 increased eotaxin-3 production (Figure 2B). Notably, cells with AG/GG produced significantly higher levels of eotaxin-3 than those with the AA genotype. However, unlike the IL-8 data, combination of IL-13 and RV16 did not further increase eotaxin-3. As other pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6) also contribute to reduced lung function in asthma [33], we measured IL-6. Overall, IL-6 levels (Figure 2C) were much lower than IL-8, and trended to be higher in cells with the AG/GG genotypes than those with the AA genotype at the baseline and under IL-13 and/or RV16 treatment, but the differences were not statistically significant, which may be in part due to the large variation of IL-6 levels in cells with the AG/GG genotypes.

Figure 2. Human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype (AG/GG) produced higher levels of IL-8 or eotaxin-3 protein upon IL-13 and/or RV16 treatment than cells with the AA genotype.

HTBE cells expressing different Tollip rs5743899 genotypes (AA = 7, AG = 6 and GG = 4) were pre-treated with or without IL-13 and then infected with RV16 for 24 hours. Cell supernatants were collected for measuring IL-8 (A), eotaxin-3 (B) and IL-6 (C) proteins. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

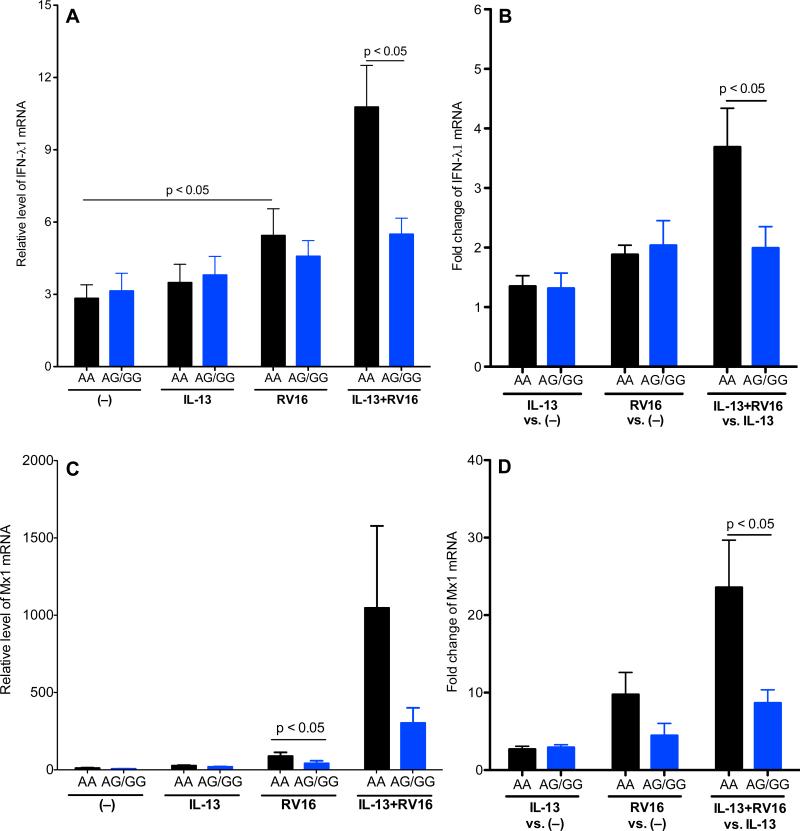

Lower levels of anti-viral gene expression in IL-13 and RV-16 treated HTBE cells with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype

As shown in Figure 3A, RV16 infection alone increased IFN-λ1 mRNA expression, particularly in cells with the AA genotype. In the presence of IL-13, RV16 infection further increased IFN-λ1 expression in cells with the AA genotype. As a result, IFN-λ1 levels were significantly lower in cells with AG/GG than the AA genotype. To further illustrate the impact of RV16 infection on IFN-λ1 induction, the fold changes of IFN-λ1 mRNA expression were determined (Figure 3B), which also demonstrated less IFN-λ1 induction in cells with AG/GG. Because IFN-λ1 induces genes such as Mx1 with direct anti-viral activity [34], we measured Mx1 expression (Figure 3C and 3D). Upon RV16 infection alone, cells with AG/GG had significantly lower levels of Mx1 mRNA expression than the AA genotype. In the presence of IL-13, Mx1 induction by RV16 in cells with AG/GG was also significantly lower than those with the AA genotype.

Figure 3. Human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype (AG/GG) demonstrated a lower anti-viral response to RV16 infection than cells with the AA genotype.

HTBE cells expressing different Tollip rs5743899 genotypes (n = 7 for AA, n = 6 for AG and n = 4 for GG) were pre-treated with or without IL-13 and then infected with RV16 for 24 hours. Cells were harvested for RNA extraction and real-time PCR to detect human IFN-λ1 (A, B) and Mx1 (C, D) genes. Data (means ± SEM) were expressed as mRNA relative levels or fold changes under IL-13 alone, RV16 alone and the combination of IL-13 and RV16.

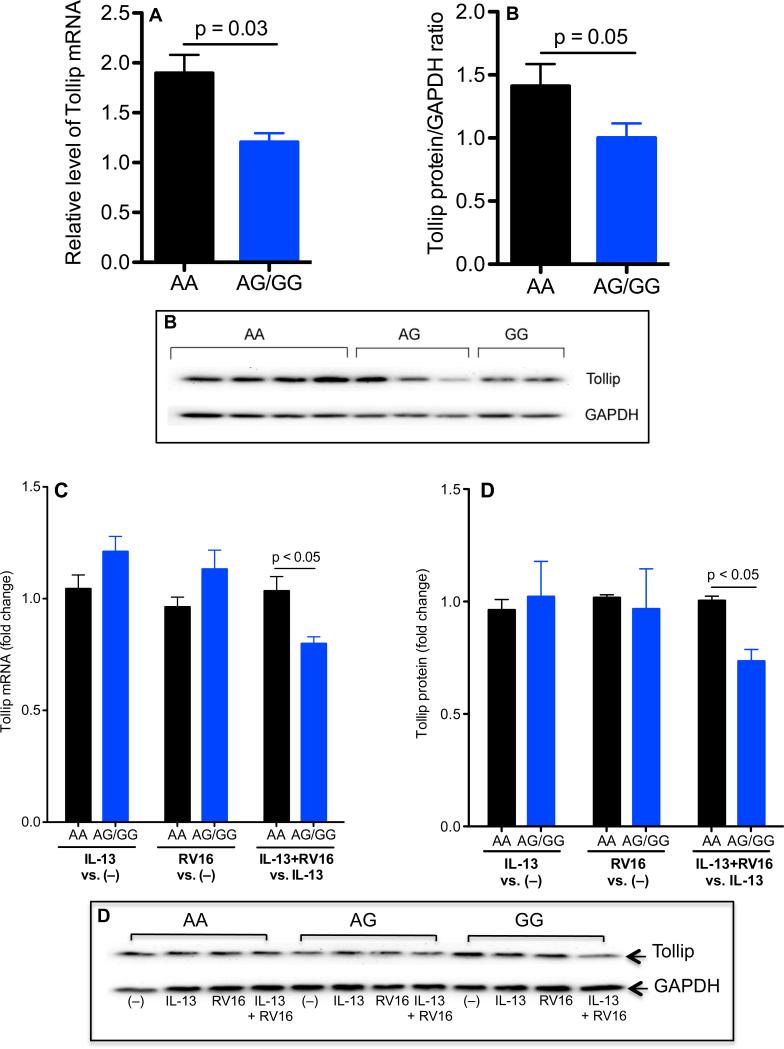

Lower baseline levels of Tollip expression in HTBE cells with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype

At the baseline (no RV16 and/or IL-13 stimulation), HTBE cells with AG/GG expressed less Tollip mRNA and protein than cells with the AA genotype (Figure 4A and 4B). Upon IL-13 treatment alone or RV16 infection alone, Tollip expression was similar among the three Tollip genotypes. However, when cells were treated with both IL-13 and RV16, Tollip levels were significantly lower in cells with AG/GG than those with the AA genotype (Figure 4C and 4D).

Figure 4. Less Tollip expression in human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype (AG/GG).

A and B: HTBE cells without stimulation were examined for Tollip mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. C and D: HTBE cells were treated with IL-13 alone, RV16 alone or the combination of both. After 24 hours of RV16 infection, Tollip mRNA (C) and protein (D) were evaluated. Data (means ± SEM) were presented as fold changes as indicated. N = 7, 6 and 4 for rs5743899 AA, AG and GG genotypes, respectively.

Effect of Tollip knockdown on IL-8 and anti-viral gene expression in HTBE cells

Tollip siRNA significantly reduced Tollip protein expression (Figure 5A). Importantly, in IL-13 and RV16 treated cells, Tollip knockdown consistently increased IL-8 production (Figure 5B), but decreased Mx1 expression (Figure 5C). However, there was no significant difference (p = 0.38) of intracellular viral levels in HTBE cells treated with Tollip siRNA (RV16 RNA relative level = 3.6±1.1) versus control siRNA (RV16 RNA relative level = 2.7±0.6).

Figure 5. Tollip knockdown increased IL-8 production and decreased anti-viral gene expression in IL-13 and RV16 treated human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells.

HTBE cells were transfected with Tollip siNRA or control siRNA, and then treated with IL-13 and RV16. After 24 hours of RV16 infection, Tollip protein (A), IL-8 protein (B) and Mx1 mRNA (C) were measured. N = 6.

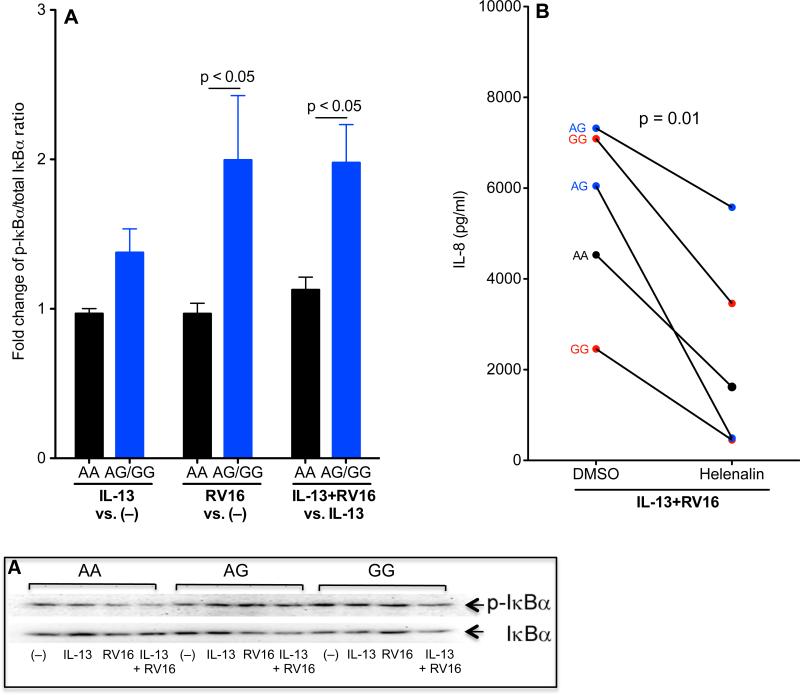

Higher levels of NF-κB activity in IL-13 and RV16 treated HTBE cells with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype

Tollip suppresses TLR signaling such as NF-κB activation [35]. To deteremine NF-κB activity, p-IκBα and total IκBα were examined. As shown in Figure 6A, RV16 infection alone or in combination with IL-13 significantly increased the p-IκBα/total IκBα ratio (an indication of NF-κB activation) in cells with AG/GG compared with the AA genotype. To confirm if NF-κB activation is required for IL-8 production upon IL-13 and RV16 treatment, cells were incubated with helenalin, a selective inhibitor that specifically alkylates the p65 subunit of NF-κB [36]. IL-8 production was similarly inhibited by helenalin in cells with different rs5743899 genotypes (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Increased IκBα degradation in IL-13 and RV16 treated human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype (AG/GG).

Western blot (A) was performed to evaluate phosphorylated-IκBα (p-IκBα) and total IκBα in HTBE cells with different Tollip rs5743899 genotypes (n = 7 for AA, n = 6 for AG and n = 4 for GG). Upper panel: Densitometry was carried out to quantify p-IκBα and total IκBα levels, and the ratios of p-IκBα versus IκBα were calculated. Fold changes of p-IκBα/total IκBα ratios at indicated conditions were used to indicate the effects of RV16 on IκBα degradation (NF-κB activation) in the absence or presence of IL-13. Lower panel: A representative Western blot image of p-IκBα and total IκBα. (B) – Effects of NF-κB inhibition on IL-8 production in IL-13 and RV16 treated HTBE cells. IL-13 and RV16 treated cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO (control) or the NF-κB inhibitor helenalin (5 μM) for 24 hours, and supernatants were harvested for IL-8 ELISA. N = 5.

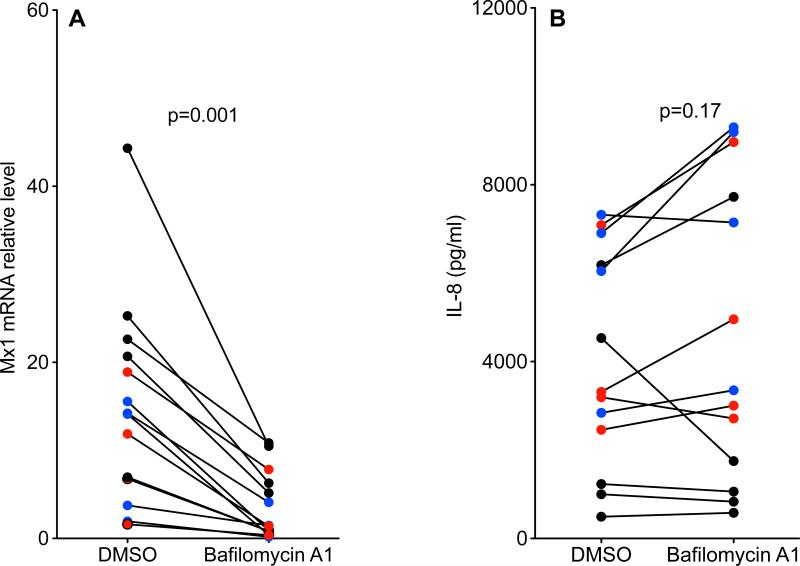

Lower levels of autophagy activity in IL-13 and RV16 treated HTBE cells with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype

Autophagic activity as reflected by the LC3II/I ratio was examined in HTBE cells (Figure 7A). When exposed to both IL-13 and RV16, cells with AG/GG demonstrated a lower LC3II/I ratio than those with the AA genotype, indicating a positive correlation between Tollip and autophagy. Co-immunoprecipitation of Tollip and LC3 demonstrated Tollip interaction with LC3 (Figure 7B). Immunofluorescent staining also indicated co-localization of Tollip and LC3 in HTBE cells (Figure 7C). In cells exposed to IL-13 and RV16, the autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1 [37, 38] significantly reduced Mx1 expression, but did not alter IL-8 production (Figure 8). These data suggest that the Tollip-autophagy pathway likely enhances the anti-viral response in IL-13-exposed cells.

Figure 7. Tollip involvement in the autophagy pathway.

(A) – Reduced LC3 II/I ratio (an indication of autophagic activity) in IL-13 and RV16 treated human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells with the Tollip rs5743899 AG or GG genotype (AG/GG). HTBE cells were treated with IL-13 alone, RV16 alone of combination of both. After 24 hours of RV16 infection, Western blot was performed to measure LC3 I and LC3 II proteins. Data (means ± SEM) were presented as fold changes as indicated. N = 7, 6 and 4 for the rs5743899 AA, AG and GG genotypes, respectively. (B) – Interaction of Tollip with LC3 was determined in HTBE cells without IL-13 and/or RV16 by immunoprecipitation of LC3, followed by immunoblotting of Tollip or LC3. N = 3 replicates. (C) – Co-localization of Tollip with LC3 was examined by immunofluorescent staining on cell sections of LC3-transfected HTBE cells.

Figure 8. Autophagy was required for the anti-viral, but not the pro-inflammatory response in IL-13 and RV16 treated human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells.

HTBE cells expressing different rs5743899 genotypes (AA = 5, black circle; AG = 4, blue circle; GG = 4, red circle) were treated with IL-13 and RV16, followed by 0.1% DMSO or bafilomycin A1 (100 nM, an autophagy inhibitor). After 24 hours of RV16 infection, Mx1 mRNA (A) and IL-8 (B) were examined.

Increased lung neutrophilic inflammation and viral load, but decreased anti-viral gene expression in Tollip knockout (KO) mice challenged with house dust mite (HDM)

To determine the in vivo function of Tollip, wild-type and Tollip KO mice were challenged with HDM and then infected with RV1B. In the absence of HDM challenges, RV1B similarly increased the lung neutrophil inflammation in wild-type and Tollip KO mice, as indicated by neutrophil levels and neutrophil chemoattractant KC in BAL fluid (Figure 9A, 9B and 9C). However, in the presence of HDM challenges, RV1B infection resulted in higher levels of lung neutrophils and KC, as well as viral load (Figure 9D) in Tollip KO mice than the wild-type mice. HDM-challenged Tollip KO mice also had less Mx1 expression (Figure 9E). Unlike the neutrophil data, BAL eosinophil and lymphocyte counts as well as IL-13 and mucin MUC5AC levels were similar between the wild-type and Tollip KO mice (data not shown). Histological analysis of lung tissue indicated a trend of increased lung inflammation such as peribronchial and perivascular infiltrate of leukocytes (mixture of neutrophils, eosinophil and monocytes) in Tollip KO mice treated with both HDM and RV1B compared with wild-type controls (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Lung inflammation and anti-viral response in allergen-challenged Tollip knockout mice.

Wild-type (WT) and Tollip knockout (KO) mice were challenged with house dust mite and then infected with RV1B. After 3 days of RV1B infection, neutrophils (A, B), chemokine KC (C) were quantified in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Anti-viral gene Mx1 mRNA (C) and viral RNA (D) were measured in the lung tissue. The horizontal bars represent the median values of indicated parameters. N = 6 to 7 mice/group.

Figure 10. Mouse lung histopathology.

A – Histological images of H&E stained lung tissues from wild-type (a, c, e and g) and Tollip KO (b, d, f and h) mice that were treated with PBS (–), RV16, HDM or the combination of HDM and RV16. B – Histopathology score. The horizontal bars represent the median values of indicated parameters. N = 6 to 7 mice/group.

Discussion

This is the first report investigating the role of Tollip SNP rs5743899 in asthma. Asthmatic subjects with the AG or GG genotype demonstrated worse lung function than those with the AA genotype. Importantly, rs5743899 modifies human airway epithelial responses to RV infection in a type 2 cytokine (i.e., IL-13) milieu. Airway epithelial cells expressing the AG or GG genotype demonstrated less Tollip expression, and mounted a higher pro-inflammatory, but a lower anti-viral response to IL-13 and RV infection. By using the Tollip knockdown and knockout approaches in human airway epithelial cells and mice exposed to IL-13 or allergens, we further revealed Tollip's dual functionality – inhibition of neutrophilic inflammation and enhancement of the anti-viral response.

Asthmatic subjects respond differently to RV infections regarding the inflammatory phenotype and disease severity [8], but the exact mechanisms are unclear. We determined whether rs5743899 affects asthma lung function, and how it may regulate airway epithelial cell responses to RV infection. We found that stable asthmatic subjects carrying rs5743899 AG or GG genotype had worse lung function as indicated by the lower FEV1/FVC ratio than those with the AA genotype. Also, there is a trend of higher frequency of the AG genotype in asthma than normal subjects. Thus, our clinical data suggest the involvement of rs5743899 in asthma.

The function of rs5743899 remains poorly understood. We found that airway epithelial cells with rs5743899 AG or GG genotype expressed less Tollip, a finding consistent with previous report in human PBMCs [13]. To determine the functional implication of rs5743899, several approaches were utilized. First, we evaluated the impact of rs5743899 genotypes on pro-inflammatory responses to IL-13 and RV16. Cells with AG/GG produced more IL-8 than cells with the AA genotype. Unlike IL-8, eotaxin-3 induction by IL-13 was not affected by RV infection. Interestingly, IL-6 levels in cells with different rs5743899 genotypes were not significantly different under various treatments. Therefore, our data suggest that IL-8 may be a more sensitive marker to predict the impact of rs5743899 on airway epithelial cell pro-inflammatory response to rhinovirus in a type 2 airway inflammation setting, and that subjects with the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype may have excessive neutrophilic inflammation upon RV infection. Our findings support the clinical findings that RV-mediated human asthma exacerbations are associated with airway neutrophilic, but not eosinophilic inflammation [8]. In a pilot study, we measured IL-8 mRNA in brushed (non-cultured) bronchial epithelial cells from severe asthmatics carrying the rs5743899 AA (n = 5) or AG (n = 3) genotype. Cells expressing the AG genotype expressed about 40 times higher IL-8 mRNA than the AA genotype, further supporting the involvement of rs5743899 in regulating airway neutrophilic inflammation. However, the sample size was small, and we will plan a large cohort and longitudinal study to determine the role of rs5743899 in RV-mediated asthma exacerbations. Second, by using the siRNA approach, we confirmed the inhibitory role of Tollip in airway epithelial pro-inflammatory response to IL-13 and RV. Third, by using the Tollip knockout mouse model, we demonstrated that Tollip may prevent excessive lung neutrophilic inflammation during allergen challenges and RV infection. Together, appropriate Tollip expression may be essential to lung homeostasis during RV infection in asthma or allergic lungs.

One of our novel findings is that epithelial cells with AG/GG express less anti-viral genes. The enhancing effect of Tollip on anti-viral gene expression was also confirmed in cultured airway epithelial cells with Tollip knockdown and in the Tollip knockout mouse model. Therefore, airways/lungs with reduced Tollip expression (e.g., asthmatic subjects with AG/GG) may be more susceptible to viral infection and excessive inflammation. Intriguingly, epithelial viral load as examined at 24 hour post RV infection was not significantly different among different rs5743899 genotypes. Moreover, Tollip knockdown in HTBE cells decreased anti-vial gene expression, but did not affect the vial load. These seemingly “contradictory” findings may be explained by the complexity of host responses to viral infection. During natural RV infection, asthmatic subjects with acute exacerbations demonstrated increased airway neutrophilic inflammation, but not higher viral load as compared to asthmatic subjects without exacerbations or normal subjects with RV infection [8]. In a human airway epithelial cell culture study [39], vitamin D decreased anti-viral genes, but did not increase viral load or replication. Interestingly, in our mouse study, Tollip knockout mice exposed to both HDM and RV demonstrated less Mx1 expression coupled with increased viral load. A prospective study in human asthmatic subjects would be needed to clearly dissect the relationships among airway inflammation, anti-viral genes and viral load.

How Tollip SNPs modulate host responses to RV infection is unknown. We focused on the impact of rs5743899 on Tollip expression, NF-κB activation and the autophagic pathway, which may regulate inflammation and immunity [40, 41]. We found less Tollip expression in HTBE cells carrying AG/GG, a finding supported by data in human PBMCs [13]. Moreover, IL-13 or RV16 alone did not alter Tollip expression, but the combination of both significantly reduced Tollip in cells with AG/GG compared with the AA genotype. Rs5743899, located in chromosome 11:1323564, is within the intron 2 of the Tollip gene [42]. How the rs5743899 AG or GG genotype regulates transcription and/or translation of Tollip particularly in the context of IL-13 and RV infection remains unclear, but Tollip promoter activity, mRNA stability and translational activity will be examined in our future studies.

Although Tollip has been shown to be a negative regulator of TLR signaling [15, 43], its role in RV infection is poorly understood. For the first time, we showed that airway epithelial cells with AG/GG expressed less Tollip, but had higher levels of NF-κB activation, which may in part explain the pro-inflammatory phenotype in IL-13 and RV treated cells. How Tollip precisely regulates NF-κB activation upon IL-13 and RV treatment awaits further investigation.

Autophagy involves the delivery of cytoplasmic components (e.g., viral proteins) to the lysosomes, contributing to host defense function. Our previous study suggested the involvement of Tollip in the completion of autophagy and the fusion of the lysosome and autophagosome [44]. In the current study, we found a crosstalk between Tollip and the autophagy pathway as Tollip interacts with LC3, a key component of autophagy. Moreover, IL-13 and RV treated airway epithelial cells with AG/GG have less autophagic activity coupled with less anti-viral gene expression. The autophagic pathway is pivotal in bacterial and viral infection, but its precise role is controversial [45, 46], potentially explained by the differences in viral strains and the local milieu in the host. Our previous work suggested that in a non-type 2 cytokine milieu, autophagy impaired the anti-viral response [10, 28]. However, as reported here, autophagy in a type 2 cytokine environment appears to promote the anti-viral response. The dual functions of autophagy in RV infection may provide a rationale to treat RV infection in normal subjects and asthmatic subjects differently.

One intriguing finding from our current study is that Tollip seems to be mainly involved in the regulation of neutrophilic but not eosinophilic inflammation during RV infection in the context of IL-13 or allergen challenges. Although the precise molecular mechanisms for the differential regulation of neutrophilic vs. eosinophilic inflammation by Tollip remains an active area of research, our data suggest that Tollip genetic variation is more likely involved in neutrophil-dominant airway inflammation in severe asthma, an endotype of asthma that is difficult to treat with corticosteroids [47, 48].

There are several limitations to our current study. First, airway epithelial cell culture experiments were performed under the submerged, but not under the air-liquid interface (ALI) conditions where cells are differentiated into the mucociliary phenotype. In previous publications [49-51], both submerged and ALI cultures have been used to determine the effects of IL-13 and/or rhinovirus on airway epithelial inflammatory and anti-viral responses. The rationale for using the submerged cell culture is to mimic the injured (denuded) asthmatic airway epithelial cells which often demonstrate a basal cell phenotype. It has been reported that cells under both submerged and ALI conditions demonstrated similar pro-inflammatory and anti-viral responses (e.g., IL-8 and IFNs) [49-51]. Recently, we performed the ALI culture of HTBE cells from two donors, one with the AA genotype, and one with the AG genotype of the Tollip SNP rs5743899. Our preliminary ALI culture data suggest a similar IL-8 response of well-differentiated airway epithelial cells to IL-13 and RV16 treatment in that cells with the AG genotype demonstrated greater IL-8 induction than cells with the AA genotype (data not shown). Nonetheless, more ALI cultures need to be performed to further confirm our submerged cell culture data. Second, as only about 50% of asthmatic subjects have the airway type 2 (e.g., IL-13) inflammation, to comprehensively dissect the role of Tollip genetic variations in the setting of other asthma phenotypes (endotypes), it would be appealing to expose airway epithelial cells to other potential stimulants such as aeroallergen, type 1 (e.g., IFN-γ) or Th17 (e.g., IL-17) cytokines. Third, we used the HDM challenge mouse model to determine the in vivo impact of Tollip on host response to rhinovirus infection under airway allergic inflammation. Alternatively, IL-13 can be delivered to mouse lungs to examine the role of Tollip in lung rhinovirus infection under a type-2 inflammation milieu.

In summary, the current study has provided a new insight into the mechanisms whereby human airways respond differently to rhinovirus infection in the context of a type 2 cytokine milieu. Understanding the genetic factor(s) and underlying mechanisms for varying responses to viral infection may advance precision medicine in asthmatic subjects experiencing acute exacerbations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health to Hong Wei Chu: R01 HL122321, R01 AI106287 and R01HL125128.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Jacobs SE, Lamson DM, St George K, Walsh TJ. Human rhinoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:135–62. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00077-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gern JE. The ABCs of rhinoviruses, wheezing, and asthma. J Virol. 2010;84:7418–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02290-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:559–68. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egli DMSA, O'Shea D, Tyrrell DL, Houghton M. The impact of the interferon-lambda family on the innate and adaptive immune response to viral infections. Emerging Microbes & Infections. 2014;3:e51. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contoli M, Message SD, Laza-Stanca V, Edwards MR, Wark PA, Bartlett NW, Kebadze T, Mallia P, Stanciu LA, Parker HL, et al. Role of deficient type III interferon-lambda production in asthma exacerbations. Nat Med. 2006;12:1023–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulraiz F, Bellinghausen C, Dentener MA, Reynaert NL, Gaajetaan GR, Beuken EV, Rohde GG, Bruggeman CA, Stassen FR. Efficacy of IFN-lambda1 to protect human airway epithelial cells against human rhinovirus 1B infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse WW, Lemanske RF, Jr., Gern JE. Role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. Lancet. 2010;376:826–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61380-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denlinger LC, Sorkness RL, Lee WM, Evans MD, Wolff MJ, Mathur SK, Crisafi GM, Gaworski KL, Pappas TE, Vrtis RF, et al. Lower airway rhinovirus burden and the seasonal risk of asthma exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1007–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0585OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Triantafilou K, Vakakis E, Richer EA, Evans GL, Villiers JP, Triantafilou M. Human rhinovirus recognition in non-immune cells is mediated by Toll-like receptors and MDA-5, which trigger a synergetic pro-inflammatory immune response. Virulence. 2011;2:22–9. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.1.13807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Q, van Dyk LF, Jiang D, Dakhama A, Li L, White SR, Gross A, Chu HW. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M (IRAK-M) promotes human rhinovirus infection in lung epithelial cells via the autophagic pathway. Virology. 2013;446:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slater L, Bartlett NW, Haas JJ, Zhu J, Message SD, Walton RP, Sykes A, Dahdaleh S, Clarke DL, Belvisi MG, et al. Co-ordinated role of TLR3, RIG-I and MDA5 in the innate response to rhinovirus in bronchial epithelium. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001178. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capelluto DG. Tollip: a multitasking protein in innate immunity and protein trafficking. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah JA, Vary JC, Chau TT, Bang ND, Yen NT, Farrar JJ, Dunstan SJ, Hawn TR. Human TOLLIP regulates TLR2 and TLR4 signaling and its polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2012;189:1737–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang G, Ghosh S. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated signaling by Tollip. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7059–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Didierlaurent A, Brissoni B, Velin D, Aebi N, Tardivel A, Kaslin E, Sirard JC, Angelov G, Tschopp J, Burns K. Tollip regulates proinflammatory responses to interleukin-1 and lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:735–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.735-742.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L, Wang L, Luo X, Zhang Y, Ding Q, Jiang X, Wang X, Pan Y, Chen Y. Tollip, an intracellular trafficking protein, is a novel modulator of the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39653–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciarrocchi A, D'Angelo R, Cordiglieri C, Rispoli A, Santi S, Riccio M, Carone S, Mancia AL, Paci S, Cipollini E, et al. Tollip is a mediator of protein sumoylation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih SC, Prag G, Francis SA, Sutanto MA, Hurley JH, Hicke L. A ubiquitin-binding motif required for intramolecular monoubiquitylation, the CUE domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:1273–81. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu K, Psakhye I, Jentsch S. Autophagic clearance of polyQ proteins mediated by ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors of the conserved CUET protein family. Cell. 2014;158:549–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein KA, Jackson WT. Human rhinovirus 2 induces the autophagic pathway and replicates more efficiently in autophagic cells. J Virol. 2011;85:9651–4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Z, Yin J, Yao C, Sun Z, Shao M, Zhang Y, Tao Z, Huang P, Tong C. Variants in the Toll-interacting protein gene are associated with susceptibility to sepsis in the Chinese Han population. Crit Care. 2011;15:R12. doi: 10.1186/cc9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, Broderick SM, Wade MS, Hysi P, Scuirba J, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:309–17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:388–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Q, Jiang D, Smith S, Thaikoottathil J, Martin RJ, Bowler RP, Chu HW. IL-13 dampens human airway epithelial innate immunity through induction of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase M. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:825–33. e822. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Asthma E, Prevention P. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockman-Schneider RA, Pickles RJ, Gern JE. Effects of vitamin D on airway epithelial cell morphology and rhinovirus replication. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cakebread JA, Haitchi HM, Xu Y, Holgate ST, Roberts G, Davies DE. Rhinovirus-16 induced release of IP-10 and IL-8 is augmented by Th2 cytokines in a pediatric bronchial epithelial cell model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Q, Jiang D, Huang C, van Dyk LF, Li L, Chu HW. Trehalose-Mediated Autophagy Impairs the Anti-Viral Function of Human Primary Airway Epithelial Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Q, Case SR, Minor MN, Jiang D, Martin RJ, Bowler RP, Wang J, Hartney J, Karimpour-Fard A, Chu HW. A novel function of MUC18: amplification of lung inflammation during bacterial infection. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:819–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C, Martin S, Pfleger C, Du J, Buckner JH, Bluestone JA, Riley JL, Ziegler SF. Cutting Edge: a novel, human-specific interacting protein couples FOXP3 to a chromatin-remodeling complex that contains KAP1/TRIM28. J Immunol. 2013;190:4470–3. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu HW, Honour JM, Rawlinson CA, Harbeck RJ, Martin RJ. Effects of respiratory Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection on allergen-induced bronchial hyperresponsiveness and lung inflammation in mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1520–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1520-1526.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman JM, Naik C, Holguin F, Ray A, Ray P, Trudeau JB, Wenzel SE. Epithelial eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3 expression: relation to asthma severity, luminal eosinophilia and age at onset. Thorax. 2012;67:1061–6. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters MC, McGrath KW, Hawkins GA, Hastie AT, Levy BD, Israel E, Phillips BR, Mauger DT, Comhair SA, Erzurum SC, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 concentrations, metabolic dysfunction, and asthma severity: a cross-sectional analysis of two cohorts. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:574–84. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pott J, Mahlakoiv T, Mordstein M, Duerr CU, Michiels T, Stockinger S, Staeheli P, Hornef MW. IFN-lambda determines the intestinal epithelial antiviral host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;08:7944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100552108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns K, Clatworthy J, Martin L, Martinon F, Plumpton C, Maschera B, Lewis A, Ray K, Tschopp J, Volpe F. Tollip, a new component of the IL-1RI pathway, links IRAK to the IL-1 receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:346–51. doi: 10.1038/35014038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadigel J, Audusseau S, Baglole CJ, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q. IL-8 production in response to cigarette smoke is decreased in epithelial cells from COPD patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shacka JJ, Klocke BJ, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Datta G, Schmidt RE, Roth KA. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits chloroquine-induced death of cerebellar granule neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1125–36. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer ML, Blohmke CJ, Falsafi R, Fjell CD, Madera L, Turvey SE, Hancock RE. Rescue of dysfunctional autophagy attenuates hyperinflammatory responses from cystic fibrosis cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:1227–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansdottir S, Monick MM, Lovan N, Powers L, Gerke A, Hunninghake GW. Vitamin D decreases respiratory syncytial virus induction of NF-kappaB-linked chemokines and cytokines in airway epithelium while maintaining the antiviral state. J Immunol. 2010;184:965–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan H, Zhang Y, Luo Z, Li P, Liu L, Wang C, Wang H, Li H, Ma Y. Autophagy mediates avian influenza H5N1 pseudotyped particle-induced lung inflammation through NF-kappaB and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L183–95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00147.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen M, Hong MJ, Sun H, Wang L, Shi X, Gilbert BE, Corry DB, Kheradmand F, Wang J. Essential role for autophagy in the maintenance of immunological memory against influenza infection. Nat Med. 2014;20:503–10. doi: 10.1038/nm.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Araujo FJ, da Silva LD, Mesquita TG, Pinheiro SK, Vital Wde S, Chrusciak-Talhari A, Guerra JA, Talhari S, Ramasawmy R. Polymorphisms in the TOLLIP Gene Influence Susceptibility to Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania guyanensis in the Amazonas State of Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukherjee S, Biswas T. Activation of TOLLIP by porin prevents TLR2-associated IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2674–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker B, Geng S, Chen K, Diao N, Yuan R, Xu X, Dougherty S, Stephenson C, Xiong H, Chu HW, Li L. Alteration of lysosome fusion and low-grade inflammation mediated by super-low-dose endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:6670–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.611442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orvedahl A, Levine B. Eating the enemy within: autophagy in infectious diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:57–69. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richetta C, Faure M. Autophagy in antiviral innate immunity. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:368–76. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ito K, Herbert C, Siegle JS, Vuppusetty C, Hansbro N, Thomas PS, Foster PS, Barnes PJ, Kumar RK. Steroid-resistant neutrophilic inflammation in a mouse model of an acute exacerbation of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:543–50. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0028OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chesne J, Braza F, Mahay G, Brouard S, Aronica M, Magnan A. IL-17 in severe asthma. Where do we stand? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1094–1101. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0859PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, Shamji BW, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Footitt J, Jerico D-R, Telcian AG, Nikonova A, Zhu J, et al. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1373–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jakiela B, Gielicz A, Plutecka H, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Mastalerz L, Bochenek G, Soja J, Januszek R, Aab A, Musial J, et al. Th2-type cytokine-induced mucus metaplasia decreases susceptibility of human bronchial epithelium to rhinovirus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:229–41. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0395OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bossios A, Psarras S, Gourgiotis D, Skevaki CL, Constantopoulos AG, Saxoni-Papageorgiou P, Papadopoulos NG. Rhinovirus infection induces cytotoxicity and delays wound healing in bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2005;6:114. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]