Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei is the causative agent of human African trypanosomiasis and nagana in cattle. Recent advances in high throughput phenotypic and interaction screens have identified a wealth of novel candidate proteins for diverse functions such as drug resistance, life cycle progression, and cytoskeletal biogenesis. Characterization of these proteins will allow a more mechanistic understanding of the biology of this important pathogen and could identify novel drug targets. However, methods for rapidly validating and prioritizing these potential targets are still being developed. While gene tagging via homologous recombination and RNA interference are available in T. brucei, a general strategy for creating the most effective constructs for these approaches is lacking. Here, we adapt Gibson assembly, a one-step isothermal process that rapidly assembles multiple DNA segments in a single reaction, to create endogenous tagging, overexpression, and long hairpin RNAi constructs that are compatible with well-established T. brucei vectors. The generality of the Gibson approach has several advantages over current methodologies and substantially increases the speed and ease with which these constructs can be assembled.

Keywords: Gibson assembly, RNAi, T. brucei

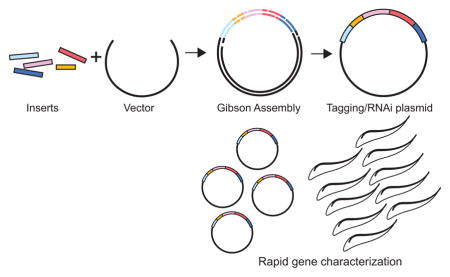

Graphical Abstract

Gibson assembly is a single-step process for rapidly assembling constructs from multiple DNA segments. We adapt the approach to generate the essential plasmids necessary for T. brucei functional genomics.

1. Introduction

Trypanosoma brucei is a protist parasite that causes enormous harm to both humans and livestock in Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The parasite has been the focus of intense research efforts, originally focusing on morphological analysis and observational studies to understand the parasite’s life cycle and how it evades the host immune response [2,3]. The advent of molecular biology has opened up a host of powerful tools for studying trypanosomes, including gene tagging and inducible expression using the tetracycline suppressor system [4,5]. Unlike several closely-related kinetoplastid parasites, T. brucei has retained the machinery necessary for RNA interference, which allows straightforward access to loss of function experiments [6,7]. These tools have been used to develop high-throughput approaches for gene analysis using inducible whole-genome RNAi and next generation sequencing (RIT-seq) [8]. This method has been used in a host of screens to identify genes involved in the parasite’s transition from the mammalian-infectious bloodstream form to the insect-resident (procyclic) form and genes that are essential for resistance to several trypanocidal agents [9,10]. Protein-protein interaction approaches such as in vivo biotinylation using a mutant of the bacterial biotin ligase BirA (BioID) and high-throughput GFP tagging have begun to uncover components of many enigmatic cytoskeletal structures that are essential for cell polarity and motility [11–14]. Advances in genomic and proteomic methods have also identified key components of different cellular pathways that merit further study [15–19].

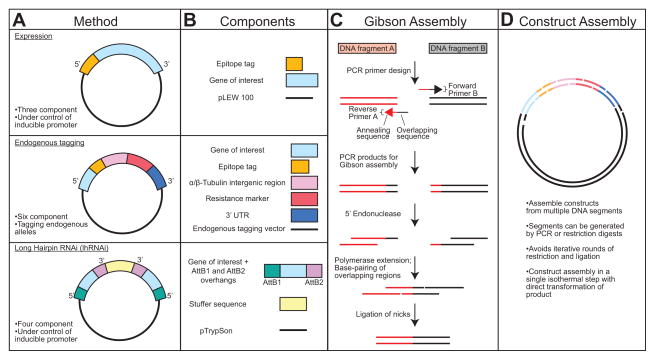

The initial characterization of T. brucei proteins relies on gene tagging for localization and tetracycline-inducible RNAi to establish function. There are numerous approaches for gene tagging, including constitutive overexpression, tetracycline-inducible overexpression, and tagging of the endogenous locus (Figure 1A, 1B) [5,11,20–24]. Epitope tags such as the HA and Ty1 tags are commonly used, along with GFP for imaging of live cells [11,25]. Tetracycline-inducible RNAi plasmids originally employed flanking T7 promoters and tetracycline suppressors to produce double-stranded RNA suitable for triggering mRNA degradation, although single-stranded long hairpin RNAs (lhRNAs) are now favored due to lower levels of background expression and improved basepairing [26–30]. While these approaches are effective, there are significant shortcomings that can decrease throughput when a large number of genes need to be assessed. Most available tagging and overexpression plasmids lack multiple restriction sites for cloning, which can require blunting or other workarounds. Endogenous tagging methods either require multiple assembly steps to clone portions of the gene of interest to direct the tag or use smaller targeting segments such as overhangs in primers, which can make PCR difficult and decrease homologous recombination efficiency, especially if the second allele is being targeted [21,31]. For the production of RNAi hairpins, intermediate steps are frequently necessary to assemble the hairpin prior to insertion into the final tetracycline-inducible plasmid [28,29]. A rapid, general strategy for making these constructs would allow more genes to be studied in a more cost-effective manner.

Figure 1. Overview of the Gibson assembly method.

[A] Three commonly used plasmids for functional genomics in T. brucei. Expression- A conventional expression vector for inducible control of a gene of interest. Endogenous tagging- A vector that introduces a tag and a selection marker to an endogenous locus. Long hairpin RNAi (lhRNAi)- A plasmid that provides inducible expression of a long hairpin RNAi for depletion of a protein of interest. [B] The specific components comprising each of the constructs described in A. [C] A schematic of the Gibson assembly process. [D] An overview of how multiple DNA segments can be assembled into a completed construct.

Gibson assembly is a single-step isothermal reaction that rapidly assembles segments of DNA with overlapping termini (Figure 1C) [32]. The method employs a mixture of three enzymes: a 5′ exonuclease that exposes overhanging sequence for specific annealing of the complimentary DNA segments, a DNA polymerase that fills in the overhangs, and a DNA ligase that links the segments. The method requires 15–20 base pairs of homologous sequence, so specificity can easily be encoded within non-annealing overhangs in PCR primers. Gibson-compatible segments can also be generated by restriction digest, which is especially useful for including plasmid backbones in the assembly reaction. Gibson assembly is remarkably robust and has been used to assemble whole genomes from small DNA segments, showing the generality of the method [33]. In this work, we show how the Gibson approach can be used to create many of the constructs used for gene analysis in T. brucei, including tetracycline-inducible expression, endogenous replacement, and RNAi (Figure 1D). The Gibson approach removes many obstacles such as restriction enzyme incompatibilities, the need for intermediate ligation steps, and the limited size of targeting segments, allowing the rapid assembly of the best-suited constructs for probing gene function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Molecular biology

Enzymes used in this study were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) and chemicals from Thermo Fisher Scientific. PCR was performed with Q5 High Fidelity Polymerase in Q5 buffer (NEB). Plasmids were prepared for transfection with GeneJET Plasmid Midiprep Kit (LifeTechnologies). PCR primers used in this work are included in Supplemental Figure 1, while the sequences of all the constructs are in Supplemental Figure 2.

2.2 Gibson Assembly

Gibson assembly, also known as isothermal chew-back-anneal assembly, was conducted as described [32]. Briefly, typically 10 μg of vector backbone was digested to generate linearized vector for assembly reactions, followed by treatment with 10 units of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (NEB) for 1 h at 37 °C. PCR was conducted using Q5 polymerase (NEB) with the manufacturer’s standard conditions to generate fragments bearing 20 bp overhangs of desired homology to the flanking region. Both vector fragments and PCR products were purified by gel purification (Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit, Zymogen) prior to assembly. Fragments were combined in either commercially available (New England Biolabs Gibson Assembly Master Mix) or homemade Gibson Assembly Master Mix. The homemade Master Mix was prepared by combining 699 μL water, 320 μL 5x isothermal reaction buffer (500 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 250 mg/mL PEG-8000, 50 mM MgCl2, 50 mM DTT, 1 mM each of four dNTPs, 5 mM beta-NAD), 0.64 μL T5 Exonuclease (Epicentre, 10 U/μL), 20 μL Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB, 2 U/μL) and 160 μL Taq DNA ligase (NEB, 40 U/μL). This solution was divided into 15 μL aliquots and stored at −20 °C. Vector to fragment ratios were variable; typically,100 ng of linearized vector was added to the mixture with a 2-fold excess of each PCR fragment. PCR fragments less than 100 bp were added at 4–6-fold excess over the vector. The mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 1 h and 10 μL was transformed into chemically competent E. coli. Plasmid DNA was isolated from colonies and assayed for the correct vector assembly by colony PCR and DNA sequencing. For sequencing pTrypSon RNAi constructs, 10 μg of DNA was linearized by overnight incubation with either PacI or AscI, followed by purification using DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research). The linearized DNA was then submitted for conventional Sanger sequencing.

2.3 Cell culture

Experiments were performed in wild type procyclic T. brucei brucei 427 strain and 427 cells carrying the machinery necessary for tetracycline inducibility (29–13). 427 cells were cultured at 28 °C in Cunningham’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma Aldrich). The 29–13 cells were cultured at 28 °C in Cunningham’s medium supplemented, 15% tetracycline free-fetal calf serum (Clontech), 50 μg/mL hygromycin and 15 μg/mL neomycin. Cell growth was monitored using a particle counter (Z2 Coulter Counter, Beckmann Coulter).

2.4 Antibodies

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: AB1 from Keith Gull (Oxford University, UK), anti-Leishmania donovani Centrin4 from Hira L. Nakhasi (Food and Drug Administration, USA), anti-Ty1 from Cynthia He (NUS, Singapore), 1B41 (Linda Kohl, CNRS, France). The monoclonal antibody against TbCentrin2 and antibodies against TbPLK have been described previously [38,45]. Mouse anti-tubulin (clone B-5-1-2) was purchased from Sigma.

2.5 Cloning and cell line assembly

All DNA constructs were validated by sequencing prior to transfection. Verified constructs were introduced into cells using electroporation with a GenePulser Xcell (BioRad) and clonal cell lines were generated by selection and limiting dilution. For plasmids based on pLEW100, 30 μg was used in each transfection, while 20 μg was used for endogenous tagging vectors.

2.6 Western blot

Cells were harvested, washed once in PBS, then lysed in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. 3×106 cell equivalents of lysate per lane were fractionated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blocked for 1 h at RT. For antibody detection, blocking and antibody dilution were done in TBS supplemented with 5% non-fat milk and 0.1% Tween-20. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by washing in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, and incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP (Jackson Immunoresearch). Clarity (BioRad) ECL substrate and a BioRad Gel Doc XR+ documentation system were used for detection.

2. 7 Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were harvested, washed once in PBS, then adhered to coverslips. For immunofluorescence, 6×105 cells per coverslip were washed once in PBS, then adhered to coverslips by centrifugation, followed by immersion in −20 °C methanol for 20 min. The cells were then air dried and rehydrated in PBS. The cells were blocked overnight at 4 °C in blocking buffer (PBS containing 3% BSA). Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated for 1 h at RT, then washed 4 times in PBS and placed in blocking buffer for 20 min. Alexa 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated for 1 h at RT. Cells were washed and mounted in Fluoromount G with DAPI (Southern Biotech). Coverslips were imaged using a Zeiss Observer Z1 equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ2 camera (Photometrics) and a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 oil immersion lens (Zeiss). AxioVision Rel. 4.8 was used to control the microscope for acquisition. All images were quantified in ImageJ and assembled for publication using Photoshop CC2015 and Illustrator CC2015.

2.8 RNAi

Cultures of TbPLK and TbCentrin2 RNAi cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/ml and induced by adding 1 μg/ml of doxycycline, while 70% ethanol was added to control cells. Cells were maintained at 28 °C and reseeded every 48 h with fresh media and doxycycline if necessary. Cells were counted every 24 h and samples taken for Western blot analysis. All cell counts are the average of three biological replicates and the error bars are the standard error.

3. Results

Tetracycline-inducible systems are commonly employed as a means to avoid toxicity and to control the degree of overexpression. The plasmid pLEW100 and its derivatives are frequently used for this purpose due to their extremely low background and highly tunable levels of expression [5]. The most common form of this plasmid contains the luciferase gene flanked by the restriction sites for HindIII and BamHI. Expression constructs are generated by excision of the luciferase by double digestion followed by insertion of a gene prepared by PCR amplification with compatible restriction sites in the primers or by digestion of an existing gene product to liberate compatible ends. Introduction of epitope tags such as HA and Ty1 into ectopically expressed constructs allows for detection without the need for specific antibodies. The limited choice of restriction enzymes for inserting genes into pLEW100 can cause problems if a site is present within the insert, especially in the case of HindIII, which lacks isoschizomers. To overcome this issue, a set of primers with 5′ overhangs that correspond to 20 base pairs at the termini of pLEW100 after HindIII/BamHI digestion can be used to insert genes via Gibson assembly. Since the PCR product does not have to be treated with restriction enzymes to generate cohesive ends for ligation, any gene can be introduced using this method.

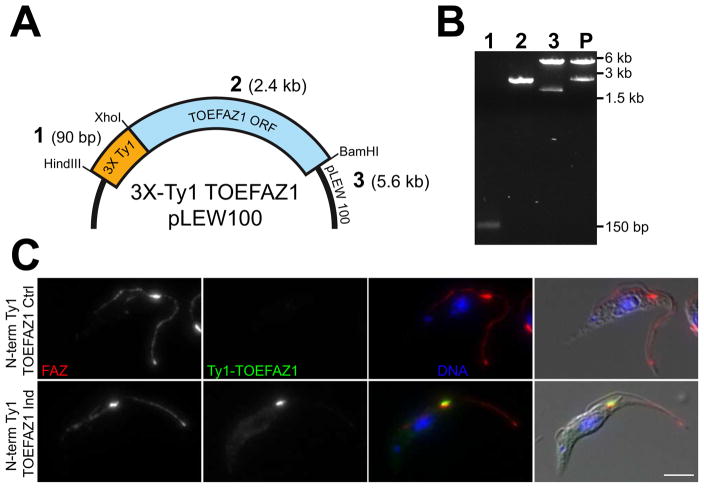

As proof of principle, we generated a construct in pLEW100 that contains the gene TOEFAZ1 (Tb927.11.15800) with three copies of the Ty1 epitope tag on its N-terminus (Figure 2A). TOEFAZ1 is found on the tip of the extending new flagellum attachment zone (FAZ) during cell division and appears to be essential for cytokinesis [34]. The triple-Ty1 tag and the TOEFAZ1 gene were PCR amplified with primers containing overhangs for Gibson assembly (Figure 2B). The pLEW100 plasmid was digested with HindIII and BamHI to produce termini that were compatible with the overhangs present in the PCR products. The two amplicons and the digested vector were assembled with the Gibson reagent and then transformed into competent bacteria. Individual transformants carrying the completed construct were identified initially by PCR screen and then by restriction digest. After validation by DNA sequencing, the construct was linearized with NotI and integrated into the rDNA spacer of the 29.13 cell line, which contains the tetracycline suppressor and T7 polymerase, allowing inducible expression [5]. In the absence of tetracycline, no Ty1-positive signal was visible (Figure 2C). In cultures treated with 1 μg/mL doxycycline (a tetracycline analog), cells that were undergoing cell division showed Ty1-positive labeling on the anterior end of the new FAZ, which is the expected localization for TOEFAZ1.

Figure 2. Gibson assembly of N-terminally tagged TOEFAZ1 in an inducible expression plasmid.

[A] Schematic of the plasmid, showing the triple-Ty1 tag (3X Ty1; 1), the TOEFAZ1 gene (TOEFAZ1 ORF; 2), and the pLEW100 vector backbone for inducible expression (pLEW100; 3). Sizes for each DNA segment are shown in parentheses. [B] Agarose gel showing the DNA segments used for Gibson assembly (1–3, as labeled in A, and the product (P) of the assembly digested with HindIII and BamHI to show the tagged insert. The asterisk in lane 3 denotes the plasmid backbone of pLEW100, which was used for the Gibson reaction. [C] Trypanosomes containing the completed plasmid where treated with vehicle control (70% EtOH) or 1 μg/mL doxycycline overnight and then fixed and stained with antibody against the FAZ (FAZ; red), anti-Ty1 (Ty1-TOEFAZ1; green), and DAPI to label DNA (DNA; blue). Scale bar is 5 μm.

Inducible overexpression constructs are useful for initial characterization of proteins at high expression levels and for testing dominant negative phenotypes, but tagging the endogenous locus is the best approach for validating protein localization. Employing the native regulatory elements present in the untranslated regions minimizes alterations in expression level and cell cycle regulation that may be present. This is especially true for trypanosomes, where most regulation of protein expression occurs at the post-transcriptional level via mRNA-binding proteins that function via the 3′ UTRs [35–37]. There are two main approaches to endogenous tagging: PCR with primers containing long (~80 bp) non-annealing overhangs that amplify a selection marker, intergenic region, and a tag such as GFP or an epitope tag [11,20,22]. The primer overhangs then target the tagging construct to the correct locus which inserts using homologous recombination after direct transfection of the PCR product. Alternatively, the tagging construct can be cloned into a plasmid that contains a larger (~500 bp) targeting sequence, which is then digested to release the completed construct prior to transfection [13,38,39]. The primer approach benefits from speed of assembly; only successful PCR is necessary to generate a construct that can then be directly introduced into cells. However, the shorter segments used for targeting can decrease the efficiency of integration. This is especially problematic if both copies of a gene need to be modified because targeting the second allele is at best half as efficient as the first. Since the targeting segments are encoded in PCR primers, it is difficult to verify their sequence prior to transfection. In our experience, UTRs isolated from the Lister 427 strains of T. brucei, which are frequently used for in vitro experiments, can vary from the published sequence, including insertions and deletions. The plasmid approach addresses most of these issues- the longer targeting segments improve the rate of homologous recombination and the DNA sequences can be isolated directly from the targeted strain and confirmed prior to transfection. The only drawback is the need for iterative cloning of the targeting sequences, which can dramatically increase the time it takes to assemble a construct.

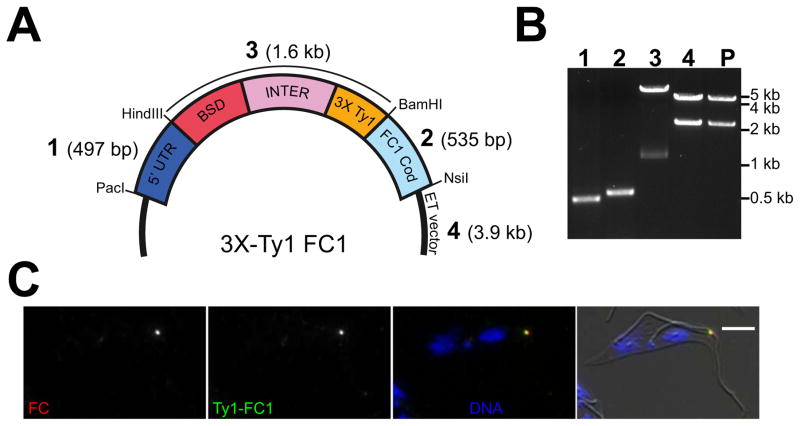

Gibson assembly allows the rapid assembly of plasmid-based targeting constructs from multiple DNA segments, which removes the biggest obstacle to their use. We have previously described a plasmid that introduces a triple-Ty1 tag at the N-terminus of targeted genes by using a 500 bp portion of the 5′ UTR and the first 500 bp of the gene without the start codon for targeting (Figure 3A) [13]. Between the two targeting segments, the vector contains the blasticidin resistance gene followed by the alpha/beta tubulin intergenic region and the Ty1 tag, flanked by PacI/HindIII restriction sites on the 5′ side and BamHI/NsiI on the 3′ side. Iteratively cloning the 5′ UTR between the PacI/HindIII sites and the beginning of the gene between the BamHI/NsiI sites generated a completed construct, which could be excised for transfection using PacI/NsiI. Using Gibson assembly, the two targeting segments can be amplified by PCR with primers containing overhangs for the plasmid backbone and either terminus of the drug-intergenic-Ty1 segment. To test this method, we attempted to create an N-terminal triple-Ty1 tagging construct for FC1 (Tb927.11.1340), a component of the flagella connector in T. brucei [34]. A Gibson reaction containing two targeting PCR products, the drug-intergenic-Ty1 segment liberated from a previously assembled vector using HindIII/BamHI digestion, and backbone plasmid digested with PacI/NsiI produced the completed vector, yielding the desired product in a single step (Figure 3B). After DNA sequencing to confirm the construct, we liberated the targeting segment by restriction with PacI and NsiI and transfected it into procyclic trypanosomes. After selection with blasticidin and clonal dilution, we were able to isolate resistant cells. Immunofluorescence showed Ty1 labeling at the tip of the new flagellum in dividing cells that colocalized with the flagellar connector marker AB1, confirming the correct tagging of FC1 (Figure 3C) [40].

Figure 3. Gibson assembly of an endogenous tagging construct for FC1.

[A] Schematic of the plasmid, showing the 5′ UTR targeting segment (1; 5′ UTR), a segment (3) containing the blasticidin selection marker (BSD), alpha/beta tubulin intergenic rection (INTER), triple-Ty1 tag (3X Ty1), the first 500 bp of FC1 (2; FC1 Cod). and the endogenous tagging vector backbone for inducible expression (ET vector, 4). Sizes for each DNA segment are shown in parentheses. [B] Agarose gel showing the DNA segments used for Gibson assembly (1–4, as labeled in A), and the product (P) of the assembly digested with PacI and NsiI to show the completed endogenous tagging insert. The asterisk in lane 3 denotes the BLA-INTER-3X Ty1 DNA segment, which was excised from a previously-assembled construct by BamHI and HindIII restriction digest. The asterisk in lane 4 denotes the ET plasmid backbone, which was isolated by PacI and NsiI digest. [C] Cells containing the FC1 endogenous tagging construct were fixed and stained with an antibody against the flagella connector (FC; red), anti-Ty1 (Ty1-FC1; green), and DAPI to label the DNA (DNA; blue). Cells were imaged by brightfield and fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar is 5 μm.

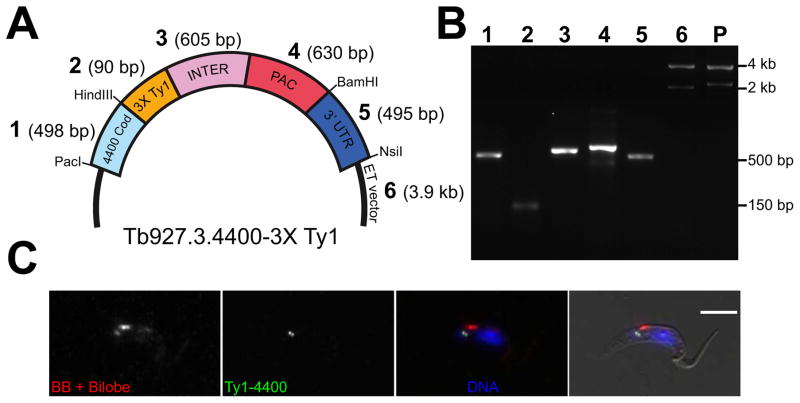

Gibson assembly not only speeds up the construction of our plasmid tagging constructs but also allows flexibility in terms of the location and type of tag appended to the gene. To demonstrate rapid de novo assembly, we created a novel C-terminal triple-Ty1 tag for the gene Tb927.3.4400, which does not tolerate N-terminal tagging because of a putative internal start site (Figure 4A) [34,41]. While alterations at the C-terminus are likely to disrupt regulation mediated by the 3′ UTR, there are instances such as internal starts and N-terminal signal sequences that require alternate approaches. To create the C-terminal tagging construct, we assembled 6 DNA segments using Gibson assembly. For targeting, we used the same digested backbone plasmid we used to make N-terminal constructs, the PCR-amplified terminal 500 bp of the gene lacking the stop codon, and the first 500 bp of the 3′ UTR for targeting using PCR (Figure 4B). For C-terminal tagging, the positions of the selection marker and epitope tag must be inverted around the intergenic sequence. We generated this segment from separate PCR products containing sequence for puromycin, the alpha/beta tubulin intergenic region, and for triple-Ty1 (Figure 4B). Combining these 6 DNA segments using Gibson assembly yielded the completed tagging construct in a single step, demonstrating the flexibility of the reaction. After DNA sequencing, the validated targeting construct was liberated from the vector by PacI/NsiI digestion and transfected into parasites. Puromycin selection and clonal dilution yielded viable parasites, which were fixed for immunofluorescence and stained with anti-Ty1 antibody. The Ty1 labeling colocalized with a marker of the basal body, suggesting that the protein is an element of the T. brucei cytoskeleton (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. De novo assembly of a tagging construct for C-terminal triple-Ty1 tagging using Gibson assembly.

[A] Schematic of the plasmid, showing the last 500 bp of the 4400 gene, which functions as a targeting segment (1; 4400 Cod), the triple-Ty1 tag (2; 3X Ty1), the alpha/beta tubulin intergenic region (3; INTER), the puromycin resistance gene (4; PAC), a 500 bp segment of the 3′ UTR of 4400 used for targeting (5; 3′ UTR), and the endogenous tagging vector backbone for inducible expression (ET vector, 6). Sizes for each DNA segment are shown in parentheses. [B] Agarose gel showing the DNA segments used for Gibson assembly (1–6, as labeled in A), and the product (P) of the assembly digested with PacI and NsiI to show the tagged insert. The asterisk in lane 6 denotes the plasmid backbone of the ET vector, which was used for the Gibson reaction. [C] Cells containing the 4400 endogenous tagging construct were fixed and stained with an antibody that detects the basal body and bilobe structure (BB + Bilobe; red), anti-Ty1 (Ty1-FC1; green), and DAPI to label the DNA (DNA; blue). Cells were imaged by brightfield and fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar is 5 μm.

Considering the value of Gibson assembly for speeding up the production of tagging constructs, we next sought to improve the speed and ease of constructing plasmids for RNAi. Currently, there are two main strategies for production of long hairpin RNAi (lhRNAi) constructs in T. brucei: a primer containing a large non-annealing 5′ overhang with a restriction site that allows the PCR product to be digested and ligated together in a head-to-tail orientation, and a Gateway-mediated recombination strategy that inserts inverted repeats of the targeted sequence on either side of a “stuffer” sequence to provide a hairpin [28,29,42]. Both methods require intermediate steps; either a restriction/ligation step in the first case or TOPO coning and Gateway recombination steps in the second. The Gateway approach, which employs the pLEW100 plasmid backbone, is especially attractive due to the tight tetracycline inducibility that can be achieved.

We developed a strategy using Gibson assembly that allows the single-step assembly of lhRNAis in pLEW100. The Gateway-mediated lhRNAi approach employs a pLEW100-derived vector known as pTrypRNAiGate that contains a stuffer sequence flanked by two AttB1/AttB2 site-specific recombination sites. Incubation with a shuttle vector containing a targeting DNA segment and a recombinase leads to incorporation of the targeting segment onto either side of a stuffer in a head-to-tail fashion. The Gibson-mediated process mimics the Gateway RNAi system by using the AttB1/AttB2 recombination sites to guide the assembly reaction. Using the pTrypRNAiGate plasmid as a guide, we made three modifications to the base pLEW100 vector to generate a vector compatible with Gibson assembly reactions [28]. First, the 3′ BamHI site in pLEW100 was replaced with the HindIII restriction site to create identical AttB1 recombination sites in pTrypRNAiGate and make the vector compatible for downstream Gibson assembly reactions (Figure 5A). Next, we altered the stuffer sequence that separates the two inverted repeats by inserting a small segment that contains the restriction sites for PacI and AscI (Figure 5A). These restriction sites allow the vector to be linearized to prevent secondary structure formation during DNA sequencing. Finally, we inserted XhoI sites flanking the AttB2 recombination sites to allow reuse of the stuffer region with a single restriction digest reaction (Figure 5A). We called the modified pLEW100 vector pTrypSon.

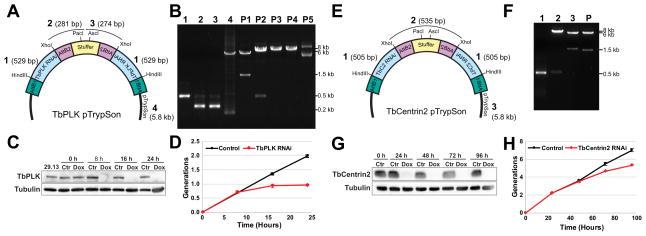

Figure 5. One-step assembly of lhRNAi constructs using Gibson assembly.

[A] Schematic of the TbPLK pTrypSon. It contains the gene sequence for triggering RNAi (1; TbPLK RNAi), one copy of AttB2 and the first half of the stuffer region (2), the second half of the stuffer region and a second copy of AttB2 in an inverted position compared to the sequence in 2 (3), an inverted second copy of the gene sequence (1), and the tetracycline-inducible plasmid (4). [B] Agarose gel showing the DNA segments used for Gibson assembly (1–4), as labeled in A, and the product (P1–5) of the assembly. P1 shows the digestion with HindIII, which liberates the full lhRNAi hairpin, P2 shows digestion with XhoI, which excises the AttB2-stuffer region, P3 and P4 show digestion with AscI and PacI, respectively, while P5 is the uncut plasmid. [C] Cells containing TbPLK pTrypSon were treated with doxycycline to initiate RNAi or vehicle control. Cell lysates were harvested from both conditions at various time points and then probed by anti-TbPLK Western blotting, (TbPLK) with anti-tubulin (Tubulin) used as a loading control. [D] TbPLK lhRNAi cells were treated with doxycycline to induce RNAi (TbPLK RNAi) or vehicle control (Control) and their growth was monitored by cell counting over 24 h. [E] The schematic of the TbCentrin2 pTrypSon. It contains the gene sequence for triggering RNAi (1; TbC2 RNAi), two copies of AttB2 flanking the stuffer region (2), an inverted second copy of the gene sequence (1), and the tetracycline-inducible plasmid (3). [F] Agarose gel showing the DNA segments used for Gibson assembly (1–3), as labeled in A, and the product (P) of the assembly, which was digested with HindIII to liberate the completed lhRNAi. The asterisk in 2 shows the stuffer sequence, which was isolated from the TbPLK pTrypSon by XhoI digest. The asterisk in 3 shows the tetracycline-inducible plasmid backbone, which was used for the assembly. [G] Cells containing the completed lhRNAi construct for TbCentrin2 depletion were treated with doxycycline to initiate RNAi or vehicle control. Cell lysates were harvested from both conditions at various time points and then probed by anti-TbCentrin2 Western blotting, (TbCentrin2) with anti-tubulin (Tubulin) used as a loading control. [D] TbCentrin2 pTrypSon cells were treated with doxycycline to induce RNAi (TbCentrin2 RNAi) or vehicle control (Control) and their growth was monitored by cell counting over 96 h.

As proof of concept we created a pTrypSon plasmid that targets TbPLK (Tb927.7.6310), an essential kinase involved in cytoskeletal biogenesis [43–45]. We selected a unique 500 bp gene segment of TbPLK suitable for RNAi using the program RNAit [46]. The segment was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR with primer overhangs homologous to the AttB1 and AttB2 sequences within the plasmid and stuffer, respectively. A Gibson reaction containing HindIII-digested pTrypGate, the two sections of the stuffer sequence, and the TbPLK-specific RNAi segment generated the completed lhRNAi hairpin plasmid in a single step (Figure 5B). After DNA sequencing to confirm the correct assembly of the hairpin, we digested the vector with NotI and transfected it into 29.13 cells to test its efficacy in depleting TbPLK. After selection of resistant clones, we induced RNAi by the addition of 1 μg/mL doxycycline and monitored TbPLK expression and cell growth. Western blotting of induced and uninduced lysates showed a dramatic decrease of TbPLK levels within 8 h of lhRNAi expression, which is expected because TbPLK is degraded at the end of each cell cycle (Figure 5C). Depletion of TbPLK lead to total block in cell division within 16 h of RNAi induction, which is similar to previously-published reports (Figure 5D) [43–45].

To demonstrate that we could recycle components of pTrypSon and further simplify the process of generating lhRNAi plasmids we generated a second pTrypSon construct, in this case directed against TbCentrin2 (Tb927.8.1080) (Figure 5E) [47]. We excised the completed stuffer segment from the TbPLK lhRNAi pTrypSon plasmid by restriction digest with XhoI, so that only a single PCR is necessary to generate the gene-specific targeting fragment. Gibson assembly with the TbCentrin2 targeting segment, stuffer, and HindIII-digested pTrypSon yielded the completed construct (Figure 5F). Prior to sequencing, the construct was linearized with PacI to avoid interference from secondary structure imparted by the hairpin structure of the DNA. Once the construct was confirmed, the plasmid was linearized with NotI and transfected into 29.13 cells as was previously done with the TbPLK construct. Resistant clones were isolated and treated with doxycycline to assess the effect of TbCentrin2 depletion. TbCentrin2 was depleted within 24 h of RNAi induction and was completely absent by 48 h (Figure 5G). Cell growth was inhibited by 72 h and remained suppressed for the remainder of the experiment (Figure 5H).

4. Discussion

The recent advances in high-throughput screens have emphasized the need for more streamlined approaches for generating DNA constructs for probing the function of candidate genes in T. brucei. Gibson assembly provides a single, unified approach for generating the ideal constructs necessary for rapidly characterizing genes with minimal modifications to currently employed plasmids. In this work, we have shown that overexpression, endogenous tagging, and RNAi plasmids can be readily assembled using Gibson assembly in a single step. Using the Gibson reagent diminishes the need for restriction enzymes, which are only necessary for generating segments as components for assembly reactions. Other commonly-used enzymes such as T4 DNA ligase are also unnecessary, further simplifying the process of generating constructs. Considering that this method does not require unique recombination sites, such as in the Gateway approach, essentially any plasmid can be adapted for Gibson assembly. The restriction sites used for conventional restriction/ligation strategies can be used to create compatible termini for assembly with PCR products or other DNA segments generated from digestion of other plasmids. The generality of Gibson assembly allows it to be used to simplify any potential cloning strategy. For example, our previous approach for endogenous tagging using a plasmid relied on iterative cloning of two targeting segments, which took approximately 7–10 days including sequencing[13,38]. With the Gibson assembly approach, the whole construct can be assembled in a single step and directly transformed, providing viable colonies to sequence the next day.

The Gibson reagent can be purchased from a variety of different vendors, although it is more cost-effective to create the enzyme mixture from its individual components, which can be done easily to generate large quantities of reagent [32]. The only increased cost for the Gibson approach is the slightly longer primers containing the overlapping sequences that are necessary for the assembly process. The 15–20 base pair overhangs are larger than those used for conventional cloning, although they are substantially shorter than those used for direct endogenous tagging by PCR (~80 base pairs) [11,20]. The increased cost of primers is offset by the decreasing cost of DNA synthesis and the diminished reliance on restriction enzymes and ligase. Designing primers for Gibson assembly is straightforward, although for constructs generated from a large number of DNA segments on-line programs are available to assist with designing overhangs and calculating melting temperatures (http://nebuilder.neb.com/).

Gibson assembly improves the speed and ease of generating each type of construct in this work. For the assembly of overexpression constructs from one or two segments of DNA, Gibson assembly is most useful when restriction enzyme incompatibilities are an issue or when a tag needs to be appended in situ, although we have observed anecdotally that larger inserts also clone more easily using the approach when compared to traditional restriction/ligation strategies. When generating endogenous tagging cassettes, Gibson assembly allows the use of larger, fully sequenced targeting segments and provides plasmids that can be archived, unlike current PCR-based strategies. The larger targeting segments substantially enhance the homologous recombination efficiency of the tagging construct. The PCR approaches for endogenous tagging are more rapid than our plasmid/Gibson approach, but the more general utility of our method makes it an important alternative, especially if the second allele of a gene is being targeted. It is also possible to rapidly create new constructs containing different tags and selection markers based on the needs of the specific experiment. For RNAi, the Gibson method allows the assembly of ideal lhRNAi constructs in a tightly inducible plasmid, all in a single step, making it the best strategy currently available. The ability to use a single reagent to assemble all of these constructs makes Gibson assembly an essential tool to expand the scale of trypanosome functional genomics.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Gibson Assembly allows the rapid assembly of multicomponent plasmids.

Currently used plasmids can be employed without modifications.

Tagging constructs and RNAi hairpins can be generated in a single 1-hour reaction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Richard Bennett for the use of his microscope, and all the labs that provided essential reagents. This work was supported by startup funds from Brown University and the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS P20 GM104317, NIAID R01AI112953, NIAID R21AI115089-01).

Abbreviations

- lhRNAi

long hairpin RNAi

- BioID

proximity-dependent biotin identification

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fèvre EM, Wissmann BV, Welburn SC, Lutumba P. The burden of human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews KR. 25 years of African trypanosome research: From description to molecular dissection and new drug discovery. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2015;200:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickerman K. Developmental cycles and biology of pathogenic trypanosomes. Br Med Bull. 1985;41:105–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirtz E, Clayton C. Inducible gene expression in trypanosomes mediated by a prokaryotic repressor. Science. 1995;268:1179–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.7761835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirtz E, Leal S, Ochatt C, Cross GA. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant-negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngô H, Tschudi C, Gull K, Ullu E. Double-stranded RNA induces mRNA degradation in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 1998;95:14687–14692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lye L-F, Owens K, Shi H, Murta SMF, Vieira AC, Turco SJ, et al. Retention and Loss of RNA Interference Pathways in Trypanosomatid Protozoans. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001161–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsford S, Turner DJ, Obado SO, Sanchez-Flores A, Glover L, Berriman M, et al. High-throughput phenotyping using parallel sequencing of RNA interference targets in the African trypanosome. Genome Res. 2011;21:915–924. doi: 10.1101/gr.115089.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mony BM, Macgregor P, Ivens A, Rojas F, Cowton A, Young J, et al. Genome-wide dissection of the quorum sensing signalling pathway in Trypanosoma brucei. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsford S, Eckert S, Baker N, Glover L, Sanchez-Flores A, Leung KF, et al. High-throughput decoding of antitrypanosomal drug efficacy and resistance. Nature. 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean S, Sunter J, Wheeler RJ, Hodkinson I, Gluenz E, Gull K. A toolkit enabling efficient, scalable and reproducible gene tagging in trypanosomatids. Open Biology. 2015;5:140197–140197. doi: 10.1098/rsob.140197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunter JD, Varga V, Dean S, Gull K. A dynamic coordination of flagellum and cytoplasmic cytoskeleton assembly specifies cell morphogenesis in trypanosomes. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:1580–1594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.166447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morriswood B, Havlicek K, Demmel L, Yavuz S, Sealey-Cardona M, Vidilaseris K, et al. Novel Bilobe Components in Trypanosoma brucei Identified Using Proximity-Dependent Biotinylation. Eukaryotic Cell. 2013;12:356–367. doi: 10.1128/EC.00326-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obado SO, Brillantes M, Uryu K, Zhang W, Ketaren NE, Chait BT, et al. Interactome Mapping Reveals the Evolutionary History of the Nuclear Pore Complex. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002365–30. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadelha C, Zhang W, Chamberlain JW, Chait BT, Wickstead B, Field MC. Architecture of a Host-Parasite Interface: Complex Targeting Mechanisms Revealed Through Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:1911–1926. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.047647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimogawa MM, Saada EA, Vashisht AA, Barshop WD, Wohlschlegel JA, Hill KL. Cell Surface Proteomics Provides Insight into Stage-Specific Remodeling of the Host-Parasite Interface in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:1977–1988. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.045146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbaniak MD, Martin DMA, Ferguson MAJ. Global quantitative SILAC phosphoproteomics reveals differential phosphorylation is widespread between the procyclic and bloodstream form lifecycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:2233–2244. doi: 10.1021/pr400086y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ericson M, Janes MA, Butter F, Mann M, Ullu E, Tschudi C. On the extent and role of the small proteome in the parasitic eukaryote Trypanosoma brucei. BMC Biol. 2014;12:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erben ED, Fadda A, Lueong S, Hoheisel JD, Clayton C. A Genome-Wide Tethering Screen Reveals Novel Potential Post-Transcriptional Regulators in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004178. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen S, Arhin GK, Ullu E, Tschudi C. In vivo epitope tagging of Trypanosoma brucei genes using a one step PCR-based strategy. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;113:171–173. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberholzer M, Morand S, Kunz S, Seebeck T. A vector series for rapid PCR-mediated C-terminal in situ tagging of Trypanosoma brucei genes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;145:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly S, Reed J, Kramer S, Ellis L, Webb H, Sunter J, et al. Functional genomics in Trypanosoma brucei: A collection of vectors for the expression of tagged proteins from endogenous and ectopic gene loci. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;154:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangs JD, Brouch EM, Ransom DM, Roggy JL. A soluble secretory reporter system in Trypanosoma brucei. Studies on endoplasmic reticulum targeting. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18387–18393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wirtz E, Hartmann C, Clayton C. Gene expression mediated by bacteriophage T3 and T7 RNA polymerases in transgenic trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3887–3894. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastin P, Bagherzadeh Z, Matthews KR, Gull K. A novel epitope tag system to study protein targeting and organelle biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaCount DJ, Barrett B, Donelson JE. Trypanosoma brucei FLA1 is required for flagellum attachment and cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17580–17588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Morris JC, Drew ME, Englund PT. Inhibition of Trypanosoma brucei Gene Expression by RNA Interference Using an Integratable Vector with Opposing T7 Promoters. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40174–40179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalidas S, Li Q, Phillips MA. A Gateway® compatible vector for gene silencing in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;178:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atayde VD, Ullu E, Kolev NG. A single-cloning-step procedure for the generation of RNAi plasmids producing long stem–loop RNA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012;184:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue M, Nakamura Y, Yasuda K, Yasaka N, Hara T, Schnaufer A, et al. The 14-3-3 proteins of Trypanosoma brucei function in motility, cytokinesis, and cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14085–14096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes RL, McCulloch R. Trypanosoma brucei homologous recombination is dependent on substrate length and homology, though displays a differential dependence on mismatch repair as substrate length decreases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3478–3493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson DG, Smith HO, Hutchison CA, Venter JC, Merryman C. Chemical synthesis of the mouse mitochondrial genome. Nat Methods. 2010;7:901–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAllaster MR, Ikeda KN, Lozano-Núñez A, Anrather D, Unterwurzacher V, Gossenreiter T, et al. Proteomic identification of novel cytoskeletal proteins associated with TbPLK, an essential regulator of cell morphogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:3013–3029. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-04-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clayton CE. Life without transcriptional control? From fly to man and back again. Embo J. 2002;21:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erben ED, Fadda A, Lueong S, Hoheisel JD, Clayton C. A Genome-Wide Tethering Screen Reveals Novel Potential Post-Transcriptional Regulators in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004178–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clayton CE. ScienceDirect Gene expression in Kinetoplastids. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;32:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Graffenried CL, Anrather D, Von Raussendorf F, Warren G. Polo-like kinase phosphorylation of bilobe-resident TbCentrin2 facilitates flagellar inheritance in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1947–1963. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-12-0911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turnock DC, Izquierdo L, Ferguson MAJ. The de novo synthesis of GDP-fucose is essential for flagellar adhesion and cell growth in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28853–28863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704742200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs LJ, McKean PG, Baines A, Moreira-Leite F, Davidge J, Vaughan S, et al. The flagella connector of Trypanosoma brucei: an unusual mobile transmembrane junction. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1641–1651. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsson D, Gunasekera K, Mani J, Osteras M, Farinelli L, Baerlocher L, et al. Spliced Leader Trapping Reveals Widespread Alternative Splicing Patterns in the Highly Dynamic Transcriptome of Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001037–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sunter J, Wickstead B, Gull K, Carrington M. A New Generation of T7 RNA Polymerase-Independent Inducible Expression Plasmids for Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35167–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar P, Wang CC. Dissociation of cytokinesis initiation from mitotic control in a eukaryote. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006;5:92–102. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.1.92-102.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammarton TC, Kramer S, Tetley L, Boshart M, Mottram JC. Trypanosoma brucei Polo-like kinase is essential for basal body duplication, kDNA segregation and cytokinesis. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1229–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Graffenried CL, Ho HH, Warren G. Polo-like kinase is required for Golgi and bilobe biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:431–438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redmond S, Vadivelu J, Field MC. RNAit: an automated web-based tool for the selection of RNAi targets in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:115–118. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(03)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He CY, Pypaert M, Warren G. Golgi duplication in Trypanosoma brucei requires Centrin2. Science. 2005;310:1196–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1119969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.