Abstract

Objective

Cognitive complaints are common features of bipolar disorder (BD). Not much is, however, known about the potential moderator effects of these factors on the outcome of talking therapies. The goal of our study was to explore whether learning and memory abilities predict risk of recurrence of mood episodes or interact with a psychological intervention.

Method

We analyzed data collected as part of a clinical trial evaluating relapse rates following Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Supportive Therapy (ST) (Meyer & Hautzinger, 2012). We included cognitive (Auditive Verbal Learning Test, general intelligence - Leistungsprüfsystem) and clinical measures from 76 euthymic patients with BD randomly assigned to either 9 months of CBT or ST and followed up for 2 years.

Results

Survival analyses including treatment condition, AVLT measures, and general intelligence revealed that recurrence of mania was predicted by verbal free recall. The significant interaction between therapy condition and free recall indicated that while in CBT recurrence of mania was unrelated to free recall performance, in ST patients with a better free recall were more likely to remain euthymic, and those with a poorer free recall were less likely to remain mania-free1.

Conclusions

These findings constitute first evidence that, when considering treatment outcome in BD, differences in verbal free recall might interact with the kind of psychotherapy provided. More research is needed to determine what other areas of cognitive functioning are related to outcome in psychological interventions.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, cognitive, psychotherapy, recurrence

Introduction

The integration of non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions has been shown to be beneficial and improves the long-term therapeutic outcomes of mood disorder patients (Lobban et al., 2007, Miklowitz et al., 2007, Oestergaard and Møldrup, 2011, Pfennig et al., 2013). The majority of studies in this field had ‘prevention of relapse’ as primary outcome measure (Castle et al., 2010, Colom et al., 2003, Oestergaard and Møldrup, 2011), but improvements in medication adherence (Colom and Lam, 2005, Pampallona et al., 2004), mood symptoms (Colom et al., 2009), quality of life, and well-being have also been reported (Zilcha-Mano et al., 2014).

While some studies concluded that interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are highly effective in bipolar disorder (BD) other trials including heterogeneous populations during both acute and euthymic phases of BD did not show significant changes in mood or relapse (Driessen and Hollon, 2010, Parikh, 2008). However, Colom et al.’s study showed that combining medication and psychosocial intervention in a stabilized population led to a reduced number of relapses and improved medication adherence, as well as improved psychosocial functioning. Notably these effects lasted up to 5 years post-intervention (Colom, Vieta, 2009)

The number of studies investigating the factors predicting the efficacy of psychological treatments is limited and usually focused on predictors such as age of onset or number of prior mood episodes (Lam et al., 2009, Reinares et al., 2014). One potential predictor or moderator of outcome could be cognitive abilities. However, only few studies have investigated this area in psychiatry and, to date, no published study has examined cognitive functioning as part of psychological treatments for bipolar disorder (BD). In a study of older adults with anxiety disorders there was a positive association between general intelligence and improvement in anxiety symptoms in the supportive counseling condition but not CBT (Doubleday et al., 2002). Similar findings by D’Alcante et al. revealed that higher verbal intelligence scores and immediate verbal recall predicted a better treatment response to both CBT and fluoxetine in adults with OCD (D'Alcante et al., 2012). Furthermore, lower intelligence scores appeared to be predictors of poor treatment response in adults with depression (Fournier et al., 2009) and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (Rizvi et al., 2009). Looking at psychosis, only a very small number of studies have investigated this issue with one study reporting that treatment response to CBT in patients with psychosis was not related to cognitive performance (Granholm et al., 2008).

This kind of research is relevant because memory, executive functions and pre-morbid intelligence are essential for completing daily activities involving goal setting and planning (Lezak, 2004). Thus, it is possible that pre-existing interindividual differences in cognitive abilities affect the extent to which people benefit from different psychological interventions (Doubleday, King, 2002). However, the literature in this field is a) very heterogeneous and b) also still controversial as a number of studies have not found a consistent link between cognitive performance and response to therapy across mood disorders (Knekt et al., 2014, Voderholzer et al., 2013). Thus, further research is needed to test this link.

Results about a potential link between cognitive functioning and outcome of talking therapies are highly relevant to BD as impairment in cognitive functions have been observed across all phases of BD (Bora et al., 2009, Glahn et al., 2007, Quraishi and Frangou, 2002), and cognitive impairment is especially pronounced during the manic and depressive phases of the disorder (Robinson et al., 2006). Additionally all of the studies we identified and that looked at whether cognitive performance is related to outcome of talking therapies have focused on acute patient populations. However, most studies evaluating psychological interventions for BD so far have focused on relapse prevention and recruited patients in remission or immediately after an acute episode. Therefore, it is not known whether neuropsychological functioning in remitted patients will predict or moderate the outcome of talking therapies.

In sum, studies focusing on the impact of neuropsychological performance on treatment response to talking therapies in general and to CBT specifically are lacking. Furthermore, it is unclear whether differences in cognitive performance in patients with BD are prospectively associated with the risk of relapse. The current paper focuses on unpublished neuropsychological data collected as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012) comparing CBT and Supportive Therapy (ST) for remitted patients with BD. In this RCT, CBT and ST were matched with regards to number and duration of sessions, and both conditions included psychoeducation and a mood diary. While CBT additionally included typical cognitive and behavioral strategies and techniques to prevent relapse or how to cope with symptoms (e.g. (Basco and Rush, 1995)), ST had a client-centered focus and was less structured and less directive. While this RCT found no overall difference in relapse rates between CBT and ST over almost 3 years, a higher number of prior mood episodes and a lower number of attended therapy sessions were associated with a shorter time before relapse. These findings suggest that characteristics shared by both treatments may contribute to the outcome. However, this prompted us to explore post hoc other potential moderators, and in this case whether indicators of general intelligence, verbal learning and memory predict recurrence of mood episodes during follow-up and whether there is an indication that cognitive performance and treatment interact. Verbal learning and memory were originally chosen because prior research showed that patients with BD demonstrated deficits in this area (Deckersbach et al., 2004, van Gorp et al., 1998)

Methods

Participants

One-hundred-forty adults with BD were either referred by local hospitals, psychiatrists, or self-referred in response to advertisements. Nine of 107 participants who completed the baseline assessment voluntary withdrew from the study (n=9) and 22 were excluded because they did not have bipolar disorder (n=20) and had current opiate or alcohol dependency (n=2). The analyses for the current paper include the clinical and cognitive data from all 76 participants which were randomized into the RCT (mean age: 44.4±11, 38 women) (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012). Participants were first invited to a screening session and eligible candidates were asked to provide informed consent. At baseline participants were administered clinical interviews (e.g. SCID-I and SCID-II) and self-rating questionnaires (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Self-Report Mania Inventory (SRMI)). Participants were included if 1. their primary diagnosis was BD based on the DSM-IV (Association and Association, 1994), 2. were aged between 18 and 65 years, and 3. were open to continue or start new medication. Exclusion criteria included 1. primary diagnosis was a non-affective disorder including schizo-affective disorder; 2. participants suffered from a major affective episode (depressed, mixed or mania according to SCID-I) or Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (Bech and Rafaelsen, 1980); 3. participants suffered from disorders associated with substance-induced affective disorder, or affective disorder due to a general medical condition; 4. substance dependency requiring detoxification (abuse would not qualify for exclusion); 5. intellectual disability (IQ<80); and 6. participants currently undergoing therapy, which means that eligible participants could not take part in additional psychological treatment [for further details see (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012)].

Procedures and Measures

At baseline an extensive assessment was undertaken including the SCID-I to assess DSM disorders as well as neuropsychological tests. A modification of the SCID was used during follow-up to assess recurrence of new mood episodes which only inquired about mood episodes since the last assessment (for further details see (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012). After the initial clinical assessment participants were randomly assigned to the CBT or ST condition including twenty 50–60 minute sessions over 9 months. Follow up assessments by raters blind to group allocation occurred at post-treatment, month 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24. In both CBT and ST, therapists provided information on BD and a mood diary was used. While the diary was used only for monitoring mood in ST, in CBT this was strategically used for psychoeducation and jointly elaborating on links between mood changes and other factors (e.g. sleep, work load). ST provided client-centered support for whatever topic the patient brought into the session, while CBT followed a structured manual which is similar to Basco and Rush (1996) including relapse prevention plans, coping strategies, communication and problem solving skills (Basco and Rush, 1995). Therapy sessions were conducted by qualified therapists with at least 1-year postgraduate training in CBT. Prior to the RCT, all therapists attended an additional 2-day workshop focusing on CBT and ST for BD including role play and video training. All therapy sessions were video-taped and weekly supervisions was provided.

As described in Meyer and Hautzinger (2012), the Somatotherapy Index (Bauer et al., 2001) was used to track medication and code adherence to mood stabilizers as the majority of the patients were on multiple medications. There was no evidence for changes in medication adherence over time or with respect to treatment conditions (for additional details on the methodology of this study see (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012)).

Cognitive functioning

At baseline participants were administered two cognitive tests: the “Leistungsprüf-System” (LPS) and the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) (Heubrock, 1992) The LPS is a standardized test evaluating intellectual abilities based on Thurstone’s model of primary abilities, (Horn, 1983) which was primarily used to check eligibility for inclusion (see above). The LPS includes six subscales (14 subtests) and constitutes a measure of general intelligence (total IQ score). The AVLT measures episodic verbal learning and memory and is similar to the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) (Delis et al., 1987). As part of the AVLT participants are read a list of 15 words for five times (List A, Trials 1–5). After each attempt there is a test of free recall of the list of words that has just been read out. After the fifth trial the researcher reads to participants an interference list containing 15 words which is followed by a free recall test of List B words. After testing the recall of the distraction list, subjects were asked to recall List A without reading this list to the participants again (i.e. score ‘Free Recall’). The verbal learning curve was estimated by the sum of the number of words recalled during trials 1 to 5 (i.e. score ‘Trial 1–5’). After a 20-minute interval participants were presented with words from list A and list B and 20 distractors and were asked to recognize which words were present in List A (i.e. score ‘Recognition’)(Heubrock, 1992). The test takes in total approximately 40 minutes.

Statistical analyses

Normality assumptions for continuous variables were examined. This revealed that square root or reciprocal transformations for the following variables were needed to achieve normality: SRMI, LPS, and AVLT variables. We conducted a series of regression analyses with “relapse” as outcome of interest to examine whether the variables age of onset, number of episodes, self-rated and clinician-administered evaluations of affective symptoms needed to be included in subsequent hierarchical regression model. Relapse was defined as any mood episode that fulfilled DSM-IV criteria. Throughout the clinical trial we monitored hospitalizations and mood episodes based on the clinician’s notes and patient’s mood diaries (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2003).

Three Cox proportional regressions were conducted to assess whether recurrence of any mood episode, of specifically mania or depression was predicted by AVLT variables and their interaction with treatment modality after controlling for baseline mood and general intelligence (i.e. LPS). The Cox model is a multiple linear regression of the logarithm of the hazard (relapse) on selected variables, with the baseline hazard being an ‘intercept’ term that varies with time. This model provides an estimate of the hazard ratio (HR) and its confidence interval. In this study HR is an estimate of the ratio of relapse rate in the CBT compared to the ST group. These three survival analyses included potential covariates (block 1), therapy condition (Block 2), LPS (block 3), Trials 1–5, Free Recall and Recognition scores (Block 4), and finally the interaction between these variables, and therapy conditions (Block 5) (Table 2). Coefficients of correlation between variables ranged from .055 (therapy condition and SRMI) to −.592 (Trials 1–5 and free recall). Correlations between interaction terms and variables were overall more elevated and ranged from .047 (interaction between therapy condition and Trials 1–5) and −.959 (interaction between therapy condition and free recall)(Table 3). Variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance scores were used to examine multicollinearity across verbal memory related variables. VIF scores ranged from 1.05 (SRMI) to 3.19 (delayed recall) and tolerance scores were >.2 prior to entering the interaction terms (see Block 4). This indicate that there was no serious problem with multicollinearity (see Field, 2013). However, after including the interaction terms as products of variables entered in previous blocks, tolerance and VIF scores indicated multicollinearity. This was to be expected as discussed in Allison (1999). In this situation, the high VIF scores and high correlations are unlikely to have adverse consequences on the analyses (Allison, 1999). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics (Version 21.0) and the overall statistical significance was defined as p≤.05.

Table 2.

Cox regression survival analysis: Models testing predictors of recurrence of mood episodes in bipolar disorder.

| 95% C.I. for Odds Ratio |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Wald | p-value | Odds Ratio | Lower | Upper | |

| Variables | ||||||

| Manic episodes | ||||||

| Block 1 | ||||||

| SRMI | 0.08 | 7.888 | <.01 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.16 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| Therapy condition | 0.25 | 0.175 | .68 | 1.29 | 0.40 | 4.20 |

| Block 3 | ||||||

| LPS | 0.05 | 0.926 | .34 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.17 |

| Block 4 | ||||||

| Trial 1–5 | −0.26 | 2.881 | .09 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.04 |

| Free recall | 1.27 | 7.312 | <.01 | 3.58 | 1.42 | 9.02 |

| Recognition | −1.25 | 3.132 | .08 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 1.14 |

| Block 5 | ||||||

| Trial 1–5 × therapy | 0.17 | 2.881 | .09 | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.50 |

| Free recall × therapy | −0.87 | 7.034 | <.01 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.80 |

| Recognition × therapy | 0.85 | 3.436 | .06 | 2.34 | 0.95 | 5.73 |

| Overall | χ2=17.21; | |||||

| χ2 (p-value) | p=.046 | |||||

| Depressive episodes | ||||||

| Block 1 | ||||||

| Therapy condition | −0.02 | .266 | .60 | 1.23 | 0.56 | 2.70 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| LPS | 0.03 | .900 | .34 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.10 |

| Block 3 | ||||||

| Trial 1–5 | 0.07 | .408 | .52 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 1.32 |

| Free recall | −0.23 | .429 | .51 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 1.59 |

| Recognition | −0.25 | .590 | .44 | 0.77 | 0.40 | 1.49 |

| Block 4 | ||||||

| Trial 1–5 × therapy | −0.04 | .357 | .55 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.09 |

| Free recall × therapy | 0.15 | .357 | .55 | 1.16 | 0.71 | 1.90 |

| Recognition × therapy | 0.19 | .777 | .37 | 1.21 | 0.79 | 1.84 |

| Overall | χ2=2.50 | |||||

| χ2 (p-value) | p=.96 | |||||

| All mood episodes | ||||||

| Block 1 | ||||||

| Therapy condition | −0.02 | 0.006 | .94 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.85 |

| Block 2 | ||||||

| LPS | 0.03 | 0.710 | .40 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.08 |

| Block 3 | ||||||

| Trial 1–5 | −0.01 | 0.018 | .89 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 1.17 |

| Free recall | 0.34 | 1.400 | .24 | 1.40 | 0.80 | 2.45 |

| Recognition | −0.47 | 2.506 | .11 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 1.12 |

| Block 4 | ||||||

| Recognition × therapy | 0.30 | 2.633 | .10 | 1.35 | 0.94 | 1.95 |

| Free recall × therapy | −0.23 | 1.427 | .23 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 1.16 |

| Trial 1–5 × therapy | 0.002 | 0.001 | .98 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.12 |

| Overall | χ2=6.26 | |||||

| χ2 (p-value) | p=.62 | |||||

Table 3.

Coefficients of correlation between predictors of recurrence of mood disorders in bipolar disorder

| Correlation Matrix of Regression Coefficients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRMI | Therapy condition |

LPS | Recognition | Delayed Recall | Trials 1–5 | Recognition × Therapy |

Delayed Recall × Therapy |

|

| Therapy condition* | .055 | |||||||

| LPS | .036 | .256 | ||||||

| Recognition | −.456 | −.131 | −.271 | |||||

| Delayed Recall | .367 | .006 | .239 | −.417 | ||||

| Trials 1–5 | .007 | −.032 | −.333 | −.251 | −.592 | |||

| Interaction 1* | .489 | .214 | .218 | −.959 | .413 | .169 | ||

| Interaction 2* | −.373 | −.066 | −.148 | .378 | −.947 | .598 | −.401 | |

| Interaction 3* | .047 | .061 | .217 | .148 | .644 | −.937 | −.072 | −.738 |

Notes: the “Therapy condition” variable was coded as 1 for CBT and 2 for ST; Interaction 1: Therapy × Recognition, Interaction 2: Therapy × Delayed Recall; Interaction 3: Therapy × Trials 1–5.

Results

Demographics

As reported in Meyer and Hautzinger’s study (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012) participants allocated to the CBT and ST therapy were comparable in terms of age, gender, and clinical status as measured by the lifetime number of mood episodes, age of onset of the disease, and severity of the depressive and manic symptoms (e.g. HAMD, SRMI). In terms of cognitive measures participants displayed a comparable performance on LPS, Trials 1–5, Free Recall and Recognition scores (p>.05) (Table 1). As reported in Meyer and Hautzinger (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012), the mean time to recurrence was 67.53 (S.E.=9.21) weeks after starting CBT therapy, and 66.25 (S.E.=10.58) weeks after ST. In particular, depressive episodes occurred 86.05 (S.E=9.75) and 88.86 (S.E.11.15) weeks after CBT and ST treatment onset. Survival times to manic/hypomanic episodes after CBT and ST were 95.85(S.E. =10.05) and 113.60 (S.E.=0.97) weeks. Time to recurrence to affective episodes of any type did not differ between therapy conditions.

Table 1.

Descriptive data of patients receiving Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Supportive Therapy (ST)

| CBT (n=38) |

ST (n=38) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 44.4±11 | 43.5±12.7 |

| Gender (n women) | 18 | 20 |

| % Bipolar I disorder | 30 (78.9) | 30 (78.9) |

| Age of onset | 26.60±9.20 | 29.8±12.40 |

| BDI | 13.50±9.80 | 11.03±7.60 |

| SRMI | 17.7±11.00 | 19.3±11.20 |

| YMRS | 4.05±5.45 | 2.29±4.64 |

| HAMD | 6.71±4.34 | 6.74±5.10 |

| AVLT - Trial 1 to 5 | 50.60±10.31 | 51.27±9.85 |

| AVLT - Free recall | 9.92±3.38 | 10.37±2.97 |

| AVLT - Recognition | 12.82±2.43 | 13.52±1.86 |

| LPS | 56.88±7.15 | 59.32±6.15 |

Note: All group comparisons are p > .05 as reported in (Meyer & Hautzinger, 2012);

AVLT = Auditive Verbal Learning Test (AVLT), BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; HAMD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; LPS = Leistungsprüfsystem (general intelligence); SRMS = Self-Report Manic Inventory, YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale.

Testing for potential covariates

A series of regression analyses with “relapse” as outcome of interest were conducted to examine whether the variables age of onset, number of prior episodes, baseline self-rated and clinician-administered evaluations of affective symptoms needed to be included in subsequent Cox regression models. These analyses revealed that there was no association between age of onset, number of mood episodes and self- or clinician-rated mood (χ2 =9.83, p=.28). Similarly none of the selected variables emerged as a significant predictor of recurrence of depressive episodes (χ2=9.6, p =.21). Although the overall model focusing on predicting recurrence of manic episodes was not significant (χ2=9.03, p=.25), self-rated manic symptoms (i.e. SRMI) was a significant predictor of manic relapse (B=.05, HR: 1.05, p=.02) and therefore was included in the analysis focusing on manic recurrence.

Cox survival analyses

The final survival models for overall time to recurrence of all mood episodes and depressive mood episodes included the AVLT variables, LPS score and therapy conditions. The model for the time till recurrence of manic episodes additionally included the SRMI score (see above). As illustrated in Table 2, the survival models related to the recurrence of overall mood episodes or depressive ones were not significant. However, when examining the model for risk of recurrence of manic episodes, the model was found to be statistically significant (χ2=17.21, p <.05).

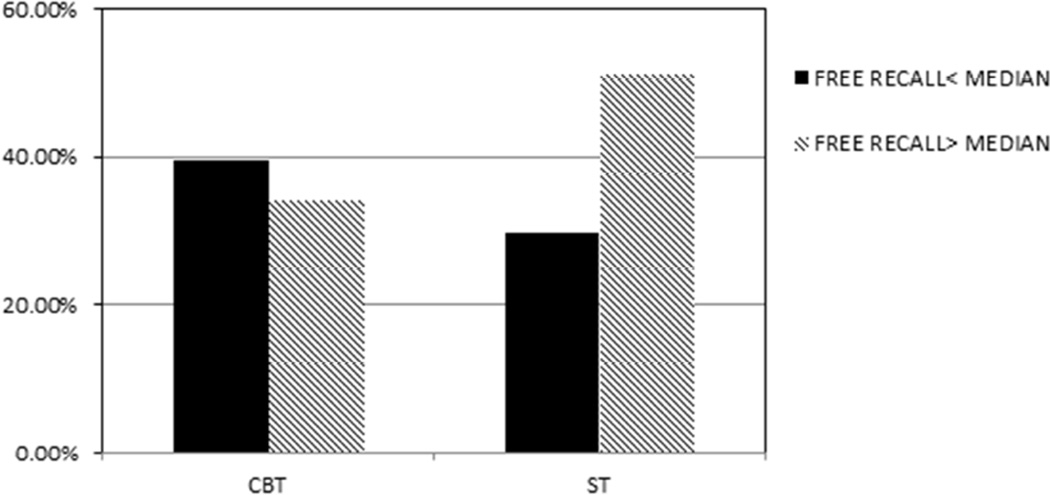

There was a significant effect of low free recall (HR: 3.58, 95% CI 1.42–9.02) (Table 2) and higher SRMS scores (HR: 1.09, 95% CI 1.03–1.16) being associated with higher rate of manic relapses. Furthermore there was a significant interaction between therapy condition and free recall (p=.008) (Table 2). Figure 1 illustrates this interaction and shows that in the CBT condition recurrence of mania was not related to free recall performance. In ST condition, however, patients with a better free recall were more likely to remain euthymic, while those with a poorer free recall were less likely to remain mania-free1.

Figure 1.

Percentages of participants without recurrence of mania lying above, on/below the median split of the free recall of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Supportive Therapy (ST)

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge this is the first study exploring whether indicators of general intelligence, verbal learning and memory predict recurrence of mood episodes in euthymic adults with BD who received either 9 months of CBT or ST. The most important finding of the post-hoc analyses of this RCT is that although there was no overall significant difference in the risk of relapse between CBT and ST (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012) and general intelligence did not predict outcome of psychotherapy, interindividual differences in verbal free recall moderated risk of recurrence of mania to a greater extent in ST than CBT. Given the exploratory nature of these findings, replications are urgently needed where assignment to treatment conditions is stratified by specifically selected neuropsychological variables (e.g. free recall), and not based on post hoc analyses.

As previous studies suggested that generally across clinical populations high verbal recall and intelligence scores are predictors of better treatment response to psychological interventions (D'Alcante, Diniz, 2012, Doubleday, King, 2002, Flessner et al., 2010, Fournier, DeRubeis, 2009, Rizvi, Vogt, 2009), the current findings may, at first, seem counterintuitive. It is, however, important to keep in mind that CBT is a highly structured, collaborative and directive approach (Beck, 1995) which might help compensate for potential interindividual differences in specific cognitive abilities. By contrast, the ST used in this study was client-focused and non-directive, which might explain why individuals with better verbal memory benefitted more from it. For instance, given the strong relationship between verbal memory and executive functioning (Hill et al., 2012, Tremont et al., 2000), it could be argued that individuals with better memory recall are probably equally proficient in activities requiring problem solving, planning and goal setting. Therefore the outcome of a supportive therapy offering emotional support, non-directive advice might be more sensitive to pre-existing differences in cognitive functioning which will affect how patients will use what has been discussed or learnt during therapy sessions. A similar effect was observed in older adults with anxiety disorders undergoing either CBT or non-directive, supportive counselling (SC) (Doubleday, King, 2002). The authors reported that individuals with higher levels of fluid intelligence who completed ST displayed lower anxiety levels than those with lower levels of fluid intelligence. However, in the CBT group, there was no association between fluid intelligence and anxiety change scores. This observation would support the hypothesis that sometimes certain features such as a highly structured intervention could play an important role for the outcome of talking therapies, and perhaps especially in the context of bipolar disorder (Colom and Vieta, 2004).

However, the question remains as to why verbal learning and memory only helped prevent mania. We suggest that mania may be more easily prevented than depression by implementing minor and straight-forward changes in behaviors such as adapting sleep-wake rhythms and reducing external stimulation. Any type of psychoeducation treatment typically provides these basic behavioral strategies to deal with emerging manic symptoms. Furthermore, these strategies may be better remembered by people with higher verbal memory skills in the absence of specific CBT techniques as guided discovery or joint review and rehearsal of information. However, as mentioned before, the role of cognitive functioning including intelligence or verbal memory and outcome of therapies is still unclear. Methodological differences between studies are likely to contribute to data inconsistency. For example, all former studies included acutely symptomatic patients, while the current trial was aimed at relapse prevention for euthymic patients. The cognitive abilities and skills negatively affected by current symptoms and during stable euthymic phases are likely to be different (Kurtz and Gerraty, 2009, Martínez-Arán et al., 2004). Therefore it is also likely that different cognitive processes and abilities will be associated with outcomes depending on the state in which patients are recruited into trials and what the actual outcome is. Our results indirectly hint at this because only verbal memory but not general intelligence interacted with the talking therapy condition, and this was also only the case for predicting recurrence of mania but not for depression.

Some limitations have to be kept in mind. First, these analyses are post hoc analyses exploring the potential role of cognitive performance. Second, we only assessed general intelligence and indicators of verbal learning/memory. This means we cannot rule out that differences in other cognitive areas such as attention or executive functioning could have been similar or even stronger predictors. Third, participants included in our study were on one or multiple medications. This means that there could have been a potential confounding effect of medication across treatments. Further, the overall model was not significant when we did not control for baseline self-reported manic symptoms. Considering that our model contained a number of variables and three interaction terms, current findings should be viewed with caution and further work would be needed to check if the results are "model dependent" and would change depending upon what other variables are included.

However, one of the strengths of this randomized control trial (RCT) of CBT for bipolar disorder was that intensity and contact duration of the two talking therapies were matched so that any differences cannot be attributed to these factors. Furthermore the follow-up covered an additional two years after the 9-month treatment period which is more than many other studies (Ball et al., 2006, Lam et al., 2005, Parikh et al., 2012). It is also important to highlight that since we used a range of enrollment strategies, the recruitment method should not have influenced the course and outcomes of this trial. In summary, although in our BD sample the effectiveness of CBT on reducing the risk of relapse was comparable to ST (Meyer and Hautzinger, 2012), interindividual differences in verbal free recall did affect outcome of patients in the CBT condition less than in the ST condition with respect to recurrence of mania. It is important to emphasize that these patients did not show neuropsychological deficits and had average levels of general intelligence. These preliminary results highlight the need for further studies on the association between interindividual differences in cognitive abilities and treatment response to psychological interventions in patients in general and more specifically with BD. However, in light of other studies it even raises the question whether different cognitive abilities will be associated with different outcomes depending on the state in which patients are starting psychological treatments. Large-scale replication studies are necessary to confirm the potential interaction between memory and the kind of psychotherapy provided.

Highlights.

We investigated the association between general intelligence, memory and relapse

We compared euthymic BD patients receiving either CBT or Supportive Therapy (ST).

Verbal recall reduces recurrence of mania to a greater extent in ST than CBT

Verbal recall may be helpful in unstructured, non-directive therapeutical settings

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the therapists and independent raters, especially Dr. Peter Peukert and Dr. Katja Salkow as well as research assistants for their enormous work, support and help.

Professor Martin Hautzinger has received honorarium from Lundbeck, Sevier, and Merk

Professor Thomas D. Meyer has been a speaker for Pfizer and Lundbeck.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by a grant provided from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG ME 1681/6-1 to 6.3) and, in part, by NIMH grant R01 085667 and the Pat Rutherford, Jr. Endowed Chair in Psychiatry (UTHealth).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Based on a reviewer’s suggestion we re-ran this analysis without controlling for baseline self-reported manic symptoms. While the overall model was not significant then (p=.778), the addition of the interaction between AVLT measures and therapy led to a non-significant increase of explained variance in the model (p=.097). Furthermore, as in the main analysis, both delayed recall (B=.972, HR=2.643, p=.032) and the interaction between therapy and delayed recall (B=−.658, HR=.518, p=.033) remained significant predictors of a higher risk of relapse into mania. This finding suggests that first controlling for baseline levels of self-rated manic symptoms - a risk factor for relapse in itself – allows for showing a potential link between cognitive performance and the outcome of the psychological treatment in those where manic symptoms were low at baseline. It could be that those baseline manic symptoms predicts early relapse (even before being sufficiently exposed to treatment) while lower verbal learning/memory skill predict relapse in the future after less structured psychological treatment.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Bauer has no conflicts of interest

Contribution

IB analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MH and TDM designed the study, wrote the protocol and collected the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Allison PD. Multiple regression: A primer. Pine Forge Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Association AP, Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ball JR, Mitchell PB, Corry JC, Skillecorn A, Smith M, Malhi GS. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: focus on long-term change. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67:277–286. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco M, Rush A. Cognitive–behavioral treatment of manic depressive disorder. New York: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Williford WO, Dawson EE, Akiskal HS, Altshuler L, Fye C, et al. Principles of effectiveness trials and their implementation in VA Cooperative Study# 430:‘Reducing the efficacy-effectiveness gap in bipolar disorder’. Journal of affective disorders. 2001;67:61–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P, Rafaelsen O. The use of rating scales exemplified by a comparison of the Hamilton and the Bech - Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1980;62:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive therapy. Wiley Online Library; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;113:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle D, White C, Chamberlain J, Berk M, Berk L, Lauder S, et al. Group-based psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196:383–388. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Lam D. Psychoeducation: improving outcomes in bipolar disorder. European Psychiatry. 2005;20:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E. A perspective on the use of psychoeducation, cognitive - behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy for bipolar patients. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, et al. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:402–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Sanchez-Moreno J, Palomino-Otiniano R, Reinares M, Goikolea J, et al. Group psychoeducation for stabilised bipolar disorders: 5-year outcome of a randomised clinical trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:260–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alcante CC, Diniz JB, Fossaluza V, Batistuzzo MC, Lopes AC, Shavitt RG, et al. Neuropsychological predictors of response to randomized treatment in obsessive– compulsive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2012;39:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Savage CR, Reilly-Harrington N, Clark L, Sachs G, Rauch SL. Episodic memory impairment in bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: the role of memory strategies. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:233–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test: Adult Version: Manual. Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Doubleday EK, King P, Papageorgiou C. Relationship between fluid intelligence and ability to benefit from cognitive-behavioural therapy in older adults: A preliminary investigation. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:423–428. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen E, Hollon SD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for mood disorders: efficacy, moderators and mediators. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33:537–555. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flessner CA, Allgair A, Garcia A, Freeman J, Sapyta J, Franklin ME, et al. The impact of neuropsychological functioning on treatment outcome in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. Depression and anxiety. 2010;27:365–371. doi: 10.1002/da.20626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Gallop R. Prediction of response to medication and cognitive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009;77:775. doi: 10.1037/a0015401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Barguil M, Barrett J, Reichenberg A, Bowden CL, et al. The Neurocognitive Signature of Psychotic Bipolar Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, Link PC, Fish S, Patterson T, Jeste DV. Neuropsychological predictors of functional outcome in Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training for older people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2008;100:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heubrock D. Der Auditiv-Verbale Lerntest (AVLT) in der klinischen und experimentellen Neuropsychologie. Durchfuhrung, Auswertung und Forschungsergebnisse. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Hill BD, Alosco M, Bauer L, Tremont G. The relation of executive functioning to CVLT-II learning, memory, and process indexes. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 2012;19:198–206. doi: 10.1080/09084282.2011.643960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn W. Leistungs-Prüf-System (LPS), 1983. Hogrefe, Göttingen; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Knekt P, Saari T, Lindfors O. Intelligence as a predictor of outcome in short-and long-term psychotherapy. Psychiatry research. 2014;220:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Gerraty RT. A meta-analytic investigation of neurocognitive deficits in bipolar illness: profile and effects of clinical state. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:551. doi: 10.1037/a0016277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DH, Burbeck R, Wright K, Pilling S. Psychological therapies in bipolar disorder: the effect of illness history on relapse prevention–a systematic review. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:474–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DH, Hayward P, Watkins ER, Wright K, Sham P. Relapse prevention in patients with bipolar disorder: cognitive therapy outcome after 2 years. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:324–329. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. USA: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lobban F, Gamble C, Kinderman P, Taylor L, Chandler C, Tyler E, et al. Enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder–ERP trial. A cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the feasibility of training care coordinators to offer enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder. BMC psychiatry. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Reinares M, Colom F, Torrent C, Sánchez-Moreno J, et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:262–270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TD, Hautzinger M. The structure of affective symptoms in a sample of young adults. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2003;44:110–116. doi: 10.1053/comp.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TD, Hautzinger M. Cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive therapy for bipolar disorders: relapse rates for treatment period and 2-year follow-up. Psychological medicine. 2012;42:1429–1439. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Wisniewski SR, Kogan JN, et al. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64:419–426. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestergaard S, Møldrup C. Improving outcomes for patients with depression by enhancing antidepressant therapy with non-pharmacological interventions: A systematic review of reviews. public health. 2011;125:357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Archives of general psychiatry. 2004;61:714–719. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh SV. Is cognitive-behavioural therapy more effective than psychoeducation in bipolar disorder? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;53:441–448. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh SV, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Yatham LN, Young LT, Patelis-Siotis I, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety treatments (CANMAT) study [CME] The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2012:803–810. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig A, Bschor T, Falkai P, Bauer M. The diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder: recommendations from the current s3 guideline. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2013;110:92. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quraishi S, Frangou S. Neuropsychology of bipolar disorder: a review. Journal of affective disorders. 2002;72:209. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinares M, Sánchez-Moreno J, Fountoulakis KN. Psychosocial interventions in bipolar disorder: What, for whom, and when. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;156:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Vogt DS, Resick PA. Cognitive and affective predictors of treatment outcome in cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2006;93:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremont G, Halpert S, Javorsky DJ, Stern RA. Differential impact of executive dysfunction on verbal list learning and story recall. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2000;14:295–302. doi: 10.1076/1385-4046(200008)14:3;1-P;FT295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gorp WG, Altshuler L, Theberge DC, Wilkins J, Dixon W. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients with and without prior alcohol dependence: a preliminary study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:41–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voderholzer U, Schwartz C, Freyer T, Zurowski B, Thiel N, Herbst N, et al. Cognitive functioning in medication-free obsessive-compulsive patients treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2013;2:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S, Dinger U, McCarthy KS, Barrett MS, Barber JP. Changes in well-being and quality of life in a randomized trial comparing dynamic psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;152–154:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]