Abstract

Genital infections with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) are a source of considerable morbidity and are a health concern for newborns exposed to virus during vaginal delivery. Additionally, HSV-2 infection diminishes the integrity of the vaginal epithelium resulting in increased susceptibility of individuals to infection with other sexually transmitted pathogens. Understanding immune protection against HSV-2 primary infection and immune modulation of virus shedding events following reactivation of the virus from latency is important for the development of effective prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines. Although the murine model of HSV-2 infection is useful for understanding immunity following immunization, it is limited by the lack of spontaneous reactivation of HSV-2 from latency. Genital infection of guinea pigs with HSV-2 accurately models the disease of humans including the spontaneous reactivation of HSV-2 from latency and provides a unique opportunity to examine virus-host interactions during latency. Although the guinea pig represents an accurate model of many human infections, relatively few reagents are available to study the immunological response to infection. To analyze the cell-mediated immune response of guinea pigs at extended periods of time after establishment of HSV-2 latency, we have modified flow-cytometry based proliferation assays and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays to detect and quantify HSV-specific cell-mediated responses during latent infection of guinea pigs. Here we demonstrate that a combination of proliferation and ELISPOT assays can be used to quantify and characterize effecter function of virus-specific immune memory responses during HSV-latency.

Keywords: guinea pig, genital tract, HSV-2 latency, cell-mediated immunity, IFN-gamma, T cell proliferation

1. Introduction

HSV-2 is an important human pathogen with approximately 16% of Americans and up to 80% of some populations worldwide being seropositive for this virus (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2010; Mbopi-Keou et al., 2000). Animal models have proven useful for understanding pathogen-host interactions as well as for testing of antiviral compounds and vaccines against HSV-2. Both murine and guinea pig models of HSV-2 genital infection have been utilized in these capacities and provide complementary information about disease pathogenesis and host response. Infection of the vaginal mucosa of mice with HSV-2 requires pre-treatment with medroxy-progesterone and results in virus replication and generalized mucocutaneous disease of the vagina rather than the vesiculo-ulcerative disease commonly observed in humans. While HSV can establish a latent infection of the sensory neurons of mice, it does not reactivate spontaneously from latency as the virus does in humans. The strength of the murine model lies in the rich repository of reagents and of the availability of gene-depleted strains of mice for examination of immune cell phenotype and protective function. By contrast, few reagents for characterizing the host response of guinea pigs are available although the guinea pig model of genital HSV-2 infection more accurately mirrors the disease in humans (Fowler et al., 1992; Stanberry, 1991) and represents a unique system to examine pathogenesis and therapeutic efficacy of candidate antiviral compounds and vaccines (Bernstein et al., 2000; Bourne et al., 2005; Veselenak et al., 2012). Genital HSV-2 infection of guinea pigs can be achieved regardless of the hormonal state of the animal and results in a self-limiting quantifiable vulvovaginitis with neurologic and urologic complications mirroring those found in human disease. Primary disease in female guinea pigs involves virus replication in genital epithelial cells which is generally limited to eight days (Bourne et al., 2002). During this time, virus reaches sensory nerve endings and is transported to nerve cell bodies in the sensory ganglia. Following a brief period of acute replication at this site, the immune system usually resolves acute virus replication by day 15 post inoculation and the virus is maintained as a lifelong, latent infection of sensory neurons. Similar to humans, guinea pigs undergo spontaneous, intermittent reactivation of virus with virus shedding which can occur in the presence or absence of clinical symptoms.

In the current studies, we modified cell-mediated immune assays to allow detection and quantification of HSV-specific T lymphocyte function in lymphoid tissues of outbred guinea pigs experiencing a latent HSV-2 infection. We optimized a flow-cytometry-based proliferation assay to detect proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and used a recently developed ELISPOT assay (Gillis et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2014) to quantify HSV-specific, IFN-γ secreting cells as a sensitive method for detecting virus-specific effector function. The availability of these assays should augment efforts to examine host-virus interactions during HSV-2 latency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Virus

HSV-2 strain MS stocks were prepared on Vero cell monolayers and stored at −80°C as described previously (Bourne et al., 1999). The replication-defective HSV-2 strain, HSV-2 dl5-29, deleted of the HSV DNA replication protein genes UL5 and UL29, and the complementary cell line V529 expressing the UL5 and UL29 proteins (Da Costa et al., 2000) were a kind gift of Dr. David Knipe (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Virus stocks were prepared as described previously by Xia et al. (Xia et al., 2014) and stored at −80°C.

2.2 Guinea pigs

Female Hartley guinea pigs (250–300g) were purchased from Charles River (Burlington, MA). Guinea pigs were maintained under specific pathogen free conditions at the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved animal research center of the University of Texas Medical Branch. All animal research was humanely conducted and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch with oversight of staff veterinarians. Guinea pigs were infected by intravaginal (ivag) inoculation with 200 μl of a suspension containing 106 PFU of HSV-2 strain MS as described previously (Bourne et al., 1999). Primary disease severity and frequency of spontaneous recurrent disease were scored daily as described previously (Valencia et al., 2013). Guinea pigs infected intravaginally 8–12 months previously with HSV-2 were used in this study.

2.3 Proliferation Assay

Responder lymphocytes from uninfected or previously infected animals were obtained from single cell suspensions of spleen, inguinal lymph node (ingLN) or mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN). Responder cells were labeled with carboxy-fluorescein succinimydl ester (CFSE, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in the dark as described previously (Nelson et al., 2011), washed and re-suspended in T cell medium Labeled cells were added to proliferation cultures at 1.6 × 106 cells and cultured for up to 96h. For assays incorporating antigen-pulsed antigen presenting cells (APC), mLN cells were collected as APC and treated with Mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 20 min at 37°C. APC were then washed and re-suspended in T cell medium (Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco Medium, 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids, 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol) and infected with HSV-2 dl 5–29, pulsed with UV-killed HSV-2, or incubated in medium-only as a control. After one hour incubation at 37°C, cells were washed and labeled with CellTracker™ Orange CMRA (CTO) (Molecular Probes) for 15 minutes in the dark as described by the manufacturer. APC were washed, re-suspended in T cell medium, and added at concentrations between 1 × 105 and 8 × 105 cells to each proliferation culture. Proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphoid cells was quantified by flow cytometric analysis. Red blood cells were removed from cultured cells by incubation in Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and cells were washed and resuspended in FACS media (10% FBS, 1% P/S, and 0.1% Na azide in RPMI). Fc receptors were blocked by incubation of cells in 24G2 Antibody (Fc Block, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in FACS medium and stained with mouse anti-guinea pig CD8, anti-guinea pig CD4, or isotype control antibody followed by APC-labeled rat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Acris by OriGene, Herford, Germany). Cells were washed and fixed in 1% formaldehyde prior to analysis. Data were acquired on a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) at the UTMB Flow cytometry Core Facility and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

2.4 ELISPOT assay

Ninety six well nitrocellulose plates were coated with protein- purified monoclonal antibodies specific for guinea pig IFNγ (V-E4.1.3 antibody, (Schafer et al., 2007), a kind gift of Dr. Hubert Schaefer, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany). After overnight incubation at 4°C, plates were blocked with 2.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. APC were prepared from single cell suspensions of autologous mLN cells pulsed with UV-killed HSV-2, infected with HSV-2 dl5-29, or treated with medium as a control as described for proliferation assay APC and were added at 4×105 cells/well in T cell medium. Serial dilutions of effector lymphocytes beginning at 1×106 cells/well from single cell suspensions of spleen, mLN, or ingLN were added in duplicate. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48hrs. Anti-guinea pig IFN-γ-specific monoclonal antibody N-G3.5 (Schafer et al., 2007) was purified from culture supernatants on protein A columns (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and biotinylated using a biotinylation kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) as described by the manufacturer and utilized as the detection antibody. At the end of culture incubation, plates were washed extensively to remove cells and the biotinylated anti-IFNγ detection antibody was added to plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were then washed and streptavidin peroxidase in 2.5% BSA/PBS was added for 1hr at 37°C. Plates were developed with aminoethylcarbamazole substrate containing H2O2. HSV-specific IFN-γ secreting cells were quantified using an ImmunoSpot reader and analyzed with ImmunoSpot software (Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH).

2.5 Statistics

Statistical differences for unpaired student t test with Welsh’s correction. Values for p <0.05 were considered significant. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1 CFSE-based proliferation assay

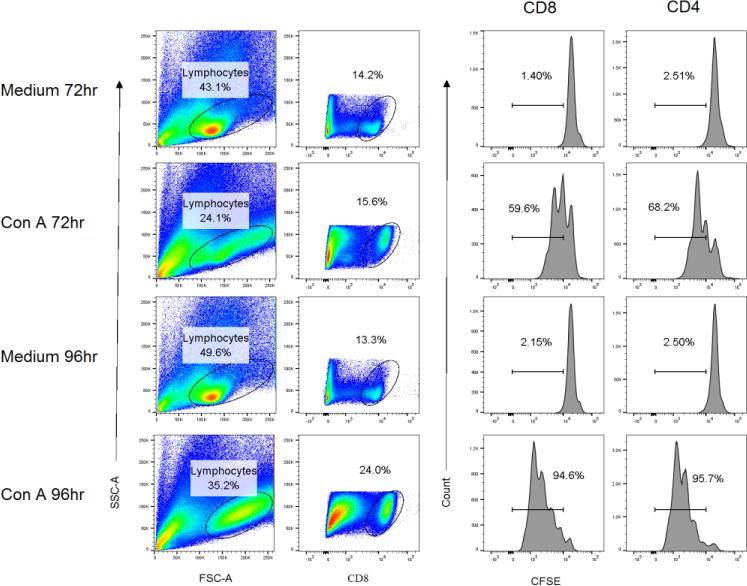

To demonstrate the feasibility of a CFSE-based flow cytometric proliferation assay for guinea pig lymphocytes, splenocytes were labeled with CFSE, cultured with Concanavalin A (Con A), and samples were stained for CD8 or CD4 at 72 or 96 hours of culture. Figure 1 shows the gating scheme for demonstrating lymphocyte proliferation in Con A-stimulated cultures. The lymphocyte gate was selected from forward and side scatter plots and the lymphocyte subset gate was selected from allophycocyanin-CD8 or -CD4 (not shown) –stained cells. CFSE staining was measured in the selected lymphocyte populations. Very low levels of proliferation were detected in medium-stimulated cells at either the 72 or 96 h time points. However, extensive CFSE dilution indicative of cell proliferation was detected at 72 h of culture and increased to include approximately 95% of both the CD8+ or CD4+ populations.

Fig. 1.

Proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ spleen lymphocytes following stimulation with Con A. Splenocytes isolated from a female Harley guinea pig were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with the T cell mitogen Con A or medium alone as a control. Cells were stained for surface expression of CD4 and CD8 and proliferation of each subset was determined by flow cytometry at 72 and 96 h of culture. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward and side scatter, and further gated on CD4+ or CD8+ (shown) cells prior to determination of CFSE dilution.

3.2 Detection of HSV-specific T cell proliferative responses

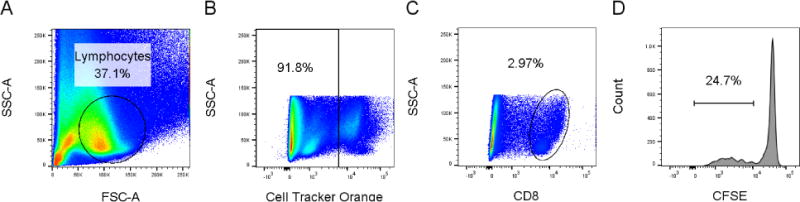

The CFSE-based assay was modified to detect antigen-specific proliferation of splenic responder lymphocytes from guinea pigs infected previously with HSV-2. The use of outbred animals made necessary the preparation of an autologous APC population for each individual animal. APC were prepared from mLN lymphocytes and infected with HSV-2 dl5-29 or cultured with medium as a control then labeled with CTO prior to culture with CFSE-labeled responder lymphocytes. Cells were stained for CD4 or CD8 a various time points after initiation of culture. Figure 2 shows the gating strategy to exclude CTO-labeled cells and measure proliferation solely in CFSE-labeled CD4+ or CD8+ responder cells. The lymphocyte gate (Fig 2a) was selected followed by selection of CTO-negative cells (Fig 2b). The CFSE-labeling of gated CD8+ (Fig 2C) or CD4+ (not shown) cells was determined (Fig 2D).

Fig. 2.

Gating strategy for detection of antigen-specific proliferation. CFSE-labeled effector lymphocytes were cultured with CTO-labeled APC. A. Forward and side scatter selection of lymphocyte population. B Gating of CTO-negative effector cells. C. Selection of CD8+ population. D. Assessment of CFSE staining of CD8+ population.

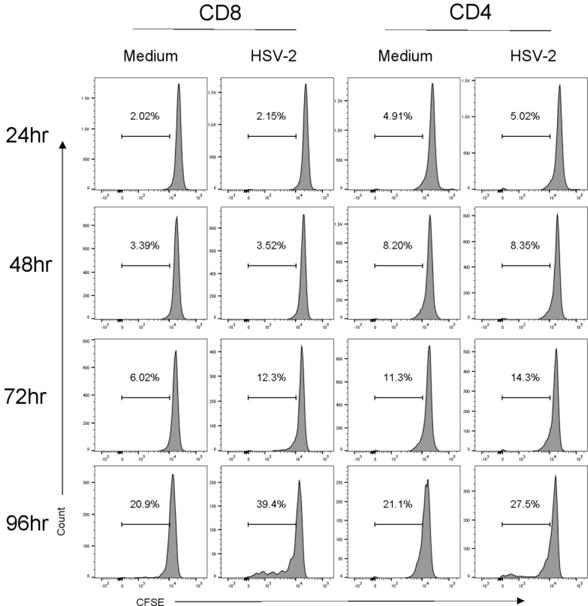

We utilized this assay to measure the proliferative capacity of memory T cells from the spleens of guinea pigs infected between 8–12 months previously with HSV-2. Flow cytometric analysis of proliferation cultures was performed at 24 h intervals up to 96 hours post culture to optimize proliferation measurement. As shown in Figure 3, only low-level background proliferation of either CD8+ or CD4+ lymphocytes was detected at any time point in medium-only control cultures. Virus-specific proliferation was detected in CD8+ lymphocytes stimulated with HSV-2-infected APC at 72h of culture that increased at the 96h time point. The HSV-specific proliferative response by CD4+ lymphocytes stimulated with HSV-infected APC was similar. Based on these results subsequent analysis of proliferative responses was measured only at the 96h time point.

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of HSV-specific proliferative response by spleen lymphocytes from guinea pigs infected 9–12 months previously with HSV-2. Splenocytes were labeled with CFSE and cultured with CTO-labeled APC infected with HSV-2 dl 5-29 or pulsed with medium as a control. Cells were stained for CD4 or CD8 at the indicated times and proliferation assessed by flow cytometry.

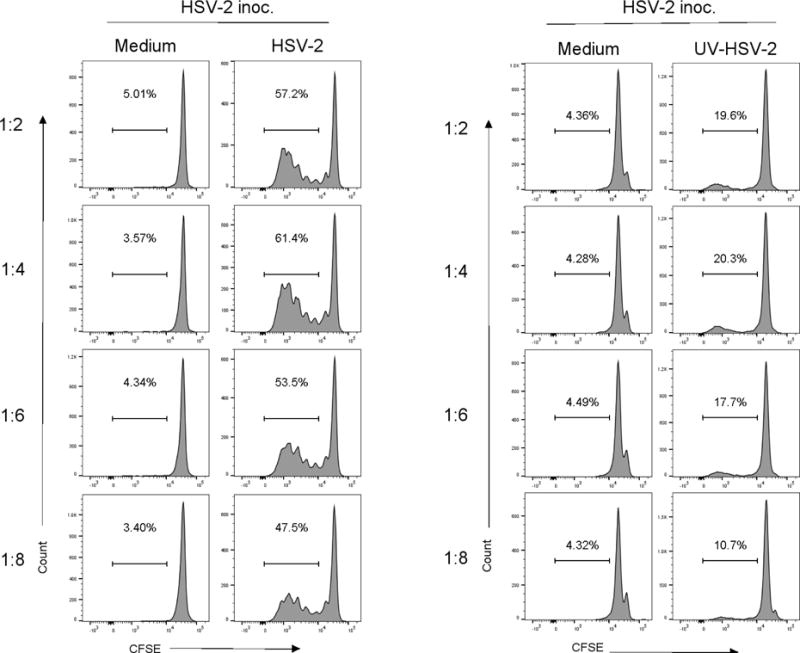

To optimize the APC component of the proliferation cultures, spleen cells from immune guinea pigs were stimulated with various concentrations of antigen-pulsed or control-treated APC populations. As shown in Figure 4a, HSV-specific proliferation of CD8+ lymphocytes was detected at all APC to responder cell ratios tested. The maximum proliferation was detected using a 1:4 APC to responder cell ratio. Similarly, maximum proliferation of CD4+ lymphocytes to UV-killed HSV-2 APC was also detected in proliferation cultures utilizing a 1:4 APC to responder cell ratio. By contrast spleen cells from non-immune guinea pigs did not respond to control-treated APC, HSV-2 dl5-29-infected APC, or UV-killed HSV-2-pulsed APC at any APC to responder cell ratio tested (Figure 1 supplemental).

Fig. 4.

Impact of altering the number of antigen presenting cells on HSV-specific proliferation of spleen lymphocytes. Splenocytes from guinea pigs infected 8–12 months previously with HSV-2 were stimulated with CTO-labeled, HSV-2 dl5-29 infected APC, UV-killed HSV-2, or medium-pulsed APC as a control at the indicated APC: responder cell ratio. Proliferation of CD8+ cells (A) or CD4+ cells (B) was determined after 96 h of culture. Results from one experiment of three performed are shown.

3.3 Detection of HSV-specific T cell responses by ELISPOT

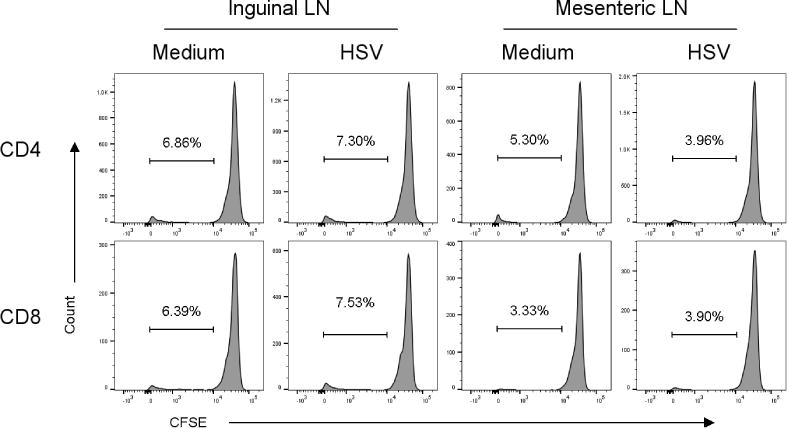

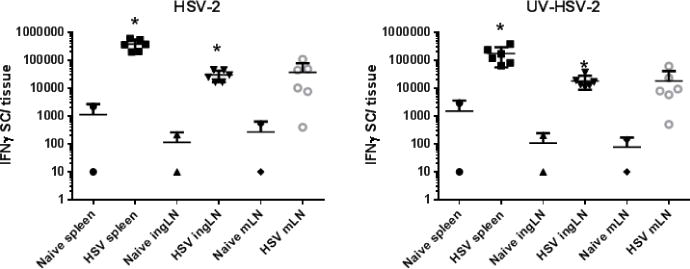

We tested for the presence of HSV-specific memory cells in ingLN and mLN by proliferation assay. As shown in Figure 5, HSV-stimulation of lymphocytes from either tissue resulted in only background proliferative responses by CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocytes. As a potentially more sensitive test for HSV-specific T cells, we tested for the presence of HSV-specific effector function in lymphocytes isolated from these same tissues of previously HSV-2 infected guinea pigs by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Xia et al., 2014). Lymphocytes were harvested from the spleens, ingLN and mLN of uninfected controls and from guinea pigs infected between 8–12 months previously with HSV-2. Lymphocytes were stimulated with APC populations pulsed with either HSV-2 dl5-29 or UV-killed HSV-2. As shown in Figure 6, only low, background numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells were detected by ELISPOT in any lymphoid tissue from uninfected control animals. By contrast, stimulation of splenocytes with HSV-2 dl5-29 infected APC resulted in detection of high numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells. Virus-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells were detected at approximately ten-fold lower numbers in ingLN or mLN of animals previously infected with HSV-2. A similar pattern was detected for lymphoid cells stimulated with UV-killed HSV-2 although lower numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells were detected. Together, these data demonstrate the ability to detect virus-specific cell mediated responses present in lymphoid tissues at long periods after infection and to characterize these populations in terms of capacity for antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine release.

Fig. 5.

HSV-specific proliferative responses are not detected in populations of inguinal and mesenteric LN cells from guinea pigs taken 8–12 months after HSV-2 infection. Cells were harvested from the indicated source and stimulated with CTO-labeled HSV-2 dl5-29 infected APC or medium pulsed APC as a control. Proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry at 96 h of culture. Results from one experiment of three performed are shown.

Fig. 6.

Detection of HSV-specific, IFN-γ secreting cells in spleen, ingLN, and mLN by ELISPOT at 12 months post infection. Single cell populations of the indicated lymphoid tissues were harvested from uninfected guinea pigs or animals infected 8–12 months previously with HSV-2. Cells were stimulated by culture with HSV-2 infected APC, UV-HSV-2 pulsed APC, or medium pulsed APC as a control. The number of spots detected in medium-APC control cultures was routinely subtracted from HSV-2 infected and UV-killed HSV-2 pulsed APC cultures to obtain the antigen-specific response. Responses of individual animals are shown and the mean response is marked as a horizontal line. * P < 0.05, Unpaired t test.

4. Discussion

The guinea pig (Cavea porcellus) has historically been utilized as a valuable tool to study innate immune responses, diet and metabolism, physiology, and infectious diseases. In fact the guinea pig provides a useful infection model for a wide variety of bacterial and viral pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Padilla-Carlin et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2009), cytomegalovirus (Schleiss, 2002), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (Greene et al., 2005), Junin virus (Seregin et al., 2010) and Chlamydia trachomatis (Rank and Sanders, 1992). For many pathogens, such as HSV-2, the disease pathology observed following infection of guinea pigs closely recapitulates that observed in human infection. Genital infection of guinea pigs results in a self-limiting acute infection of the genital epithelium that can be clinically scored for quantification of disease severity. Importantly, spontaneous reactivation of HSV-2 in guinea pigs results in recurrent disease and virus shedding from the vaginal epithelium which can also be quantified. Therefore, a number of clinically relevant endpoints can be assessed during preclinical testing of candidate antiviral agents or vaccines including impact of candidate therapeutics on the incidence and severity of primary and recurrent HSV disease and on the frequency and magnitude of virus shedding (Bourne et al., 2005).

A major limitation of the guinea pig model has been the availability of only a limited number of reagents for characterizing immune responses and for development of immunological assays. We recently developed assays to detect and quantify HSV-specific antibody secreting cells in lymphoid and peripheral tissues of HSV-2 infected guinea pigs (Milligan et al., 2005; Xia et al., 2014). Cell-mediated responses have been assessed previously in other immunization systems as the antigen-specific proliferation of lymphocyte populations from immune animals through the use of 3H thymidine uptake assays (Cho and McMurray, 2007) or MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide) dye-based proliferation assays (Nanda et al., 2014; Terhuja et al., 2015). Previous studies by others in an HSV-2 model utilized a novel cytotolytic assay and 3H thymidine uptake assays to characterize cell-mediated responses of guinea pigs to therapeutic immunization during the early stages of HSV-2 latency (Bernstein et al., 1991). While antigen-specific proliferation of immune cells is measured in these assays, the results provide no indication of the specific proliferation of defined lymphocyte subpopulations. In the current study, utilizing a flow cytometric-based proliferation assay, we detected HSV-specific proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in the spleens of guinea pigs infected 8–12 months previously with HSV-2. Moreover, the assay was compatible with the use of either live or UV-killed antigen to stimulate immune cell populations. While antigen-specific proliferation was detectable by 72h post antigen-stimulation, the response peaked at 96h post stimulation. Interestingly, HSV-specific, CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte proliferation was readily detected in lymphocytes from the spleen, but not the mLN or ingLN, suggesting either a lack of antigen-specific lymphocytes at these sites or a limitation in the ability of the proliferation assay to detect antigen-specific activity of low magnitude. We therefore used a virus-specific ELISPOT assay in conjunction with proliferation assays to detect cell-mediated immune responses at late time points after infection. A CMV peptide-specific ELISPOT assay to detect IFN-γ -secreting cell responses in immunized guinea pigs has recently been described (Gillis et al., 2014) and adaptations of this assay have been utilized to detect Shigella flexneri-specific (Yan et al., 2014) and HSV-specific (Xia et al., 2014) cell-mediated responses. Lymphocyte populations from HSV-infected, but not uninfected, guinea pigs responded to stimulation with APC infected with a replication-defective strain of HSV-2. The number of HSV-specific, IFN-γ-secreting cells was approximately 10-fold lower in mLN and ingLN cells compared to splenic cell populations which may explain the diminished ability to detect proliferative responses in lymphocytes from these tissues.

The present study demonstrates the development of immune assays to detect and characterize HSV-specific cell-mediated immune responses present in lymphoid tissues at late time points (8–12 months) after genital HSV-2 infection. A combination of proliferation assay and ELISPOT assay allowed for detection and quantification of virus-specific cell-mediated responses measured as antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production, both important effector functions of virus-specific memory T cells. Together these assays strengthen the ability to measure and characterize cell-mediated immunity in guinea pig infectious disease models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants AI105962 and AI107784 from the National Institutes of Health. JX was supported by a Sealy Center for Vaccine Development Pre-doctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bernstein DI, Harrison CJ, Jenski LJ, Myers MG, Stanberry LR. Cell-mediated immunologic responses and recurrent genital herpes in the guinea pig. Effects of glycoprotein immunotherapy. J Immunol. 1991;146:3571–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DI, Ireland J, Bourne N. Pathogenesis of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex type 2 isolates in animal models of genital herpes: models for antiviral evaluations. Antiviral Res. 2000;47:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne N, Ireland J, Stanberry LR, Bernstein DI. Effect of undecylenic acid as a topical microbicide against genital herpes infection in mice and guinea pigs. Antiviral Res. 1999;40:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne N, Milligan GN, Stanberry LR, Stegall R, Pyles RB. Impact of immunization with glycoprotein D2/AS04 on herpes simplex virus type 2 shedding into the genital tract in guinea pigs that become infected. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:2117–2123. doi: 10.1086/498247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne N, Pyles RB, Bernstein DI, Stanberry LR. Modification of primary and recurrent genital herpes in guinea pigs by passive immunization. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2797–2801. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-11-2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., Prevention. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among persons aged 14–49 years–United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:456–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, McMurray DN. Recombinant guinea pig TNF-alpha enhances antigen-specific type 1 T lymphocyte activation in guinea pig splenocytes. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa X, Kramer MF, Zhu J, Brockman MA, Knipe DM. Construction, phenotypic analysis, and immunogenicity of a UL5/UL29 double deletion mutant of herpes simplex virus 2. J Virol. 2000;74:7963–7971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7963-7971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SL, Harrison CJ, Myers MG, Stanberry LR. Outcome of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in guinea pigs. J Med Virol. 1992;36:303–308. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890360413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis PA, Hernandez-Alvarado N, Gnanandarajah JS, Wussow F, Diamond DJ, Schleiss MR. Development of a novel, guinea pig-specific IFN-gamma ELISPOT assay and characterization of guinea pig cytomegalovirus GP83-specific cellular immune responses following immunization with a modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA)-vectored GP83 vaccine. Vaccine. 2014;32:3963–3970. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene IP, Paessler S, Anishchenko M, Smith DR, Brault AC, Frolov I, Weaver SC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in the guinea pig model: evidence for epizootic virulence determinants outside the E2 envelope glycoprotein gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbopi-Keou FX, Gresenguet G, Mayaud P, Weiss HA, Gopal R, Matta M, Paul JL, Brown DW, Hayes RJ, Mabey DC, Belec L. Interactions between herpes simplex virus type 2 and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in African women: opportunities for intervention. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1090–1096. doi: 10.1086/315836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan GN, Meador MG, Chu CF, Young CG, Martin TL, Bourne N. Long-term presence of virus-specific plasma cells in sensory ganglia and spinal cord following intravaginal inoculation of herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 2005;79:11537–11540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11537-11540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda RK, Hajam IA, Edao BM, Ramya K, Rajangam M, Chandra Sekar S, Ganesh K, Bhanuprakash V, Kishore S. Immunological evaluation of mannosylated chitosan nanoparticles based foot and mouth disease virus DNA vaccine, pVAC FMDV VP1-OmpA in guinea pigs. Biologicals. 2014;42:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MH, Bird MD, Chu CF, Johnson AJ, Friedrich BM, Allman WR, Milligan GN. Rapid clearance of herpes simplex virus type 2 by CD8+ T cells requires high level expression of effector T cell functions. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;89:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Carlin DJ, McMurray DN, Hickey AJ. The guinea pig as a model of infectious diseases. Comp Med. 2008;58:324–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank RG, Sanders MM. Pathogenesis of endometritis and salpingitis in a guinea pig model of chlamydial genital infection. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:927–936. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer H, Kliem G, Kropp B, Burger R. Monoclonal antibodies to guinea pig interferon-gamma: tools for cytokine detection and neutralization. J Immunol Methods. 2007;328:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Animal models of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: an overview of progress in the characterization of guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) J Clin Virol. 2002;25(Suppl 2):S37–49. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seregin AV, Yun NE, Poussard AL, Peng BH, Smith JK, Smith JN, Salazar M, Paessler S. TC83 replicon vectored vaccine provides protection against Junin virus in guinea pigs. Vaccine. 2010;28:4713–4718. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanberry LR. Evaluation of herpes simplex virus vaccines in animals: the guinea pig vaginal model. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 11):S920–923. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_11.s920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhuja M, Saravanan P, Tamilselvan RP. Comparative efficacy of virus like particle (VLP) vaccine of foot-and-mouth-disease virus (FMDV) type O adjuvanted with poly I:C or CpG in guinea pigs. Biologicals. 2015;43:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia F, Veselenak RL, Bourne N. In vivo evaluation of antiviral efficacy against genital herpes using mouse and guinea pig models. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1030:315–326. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-484-5_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veselenak RL, Shlapobersky M, Pyles RB, Wei Q, Sullivan SM, Bourne N. A Vaxfectin((R))-adjuvanted HSV-2 plasmid DNA vaccine is effective for prophylactic and therapeutic use in the guinea pig model of genital herpes. Vaccine. 2012;30:7046–7051. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Hall Y, Orme IM. Evaluation of new vaccines for tuberculosis in the guinea pig model. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Veselenak RL, Gorder SR, Bourne N, Milligan GN. Virus-specific immune memory at peripheral sites of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in guinea pigs. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Wang D, Liang F, Fu L, Guo C. HPV16L1-attenuated Shigella recombinant vaccine induced strong vaginal and systemic immune responses in guinea pig model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:3491–3498. doi: 10.4161/hv.36084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.