Abstract

Objective To determine patient perception of residual risk after receiving a negative non-invasive prenatal testing result.

Introduction Recent technological advances have yielded a new method of prenatal screening, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT), which uses cell-free fetal DNA from the mother's blood to assess for aneuploidy. NIPT has much higher detection rates and positive predictive values than previous methods however, NIPT is not diagnostic. Past studies have demonstrated that patients may underestimate the limitations of prenatal screening; however, patient perception of NIPT has not yet been assessed.

Methods and Materials We conducted a prospective cohort study to assess patient understanding of the residual risk for aneuploidy after receiving a negative NIPT result. Ninety-four participants who had prenatal genetic counseling and a subsequent negative NIPT were surveyed.

Results There was a significant decline in general level of worry after a negative NIPT result (p = <0.0001). The majority of participants (61%) understood the residual risk post NIPT. Individuals with at least four years of college education were more likely to understand that NIPT does not eliminate the chance of trisomy 13/18 (p = 0.012) and sex chromosome abnormality (p = 0.039), and were more likely to understand which conditions NIPT tests for (p = 0.021), compared to those women with less formal education.

Conclusion These data demonstrate that despite the relatively recent implementation of NIPT into obstetric practice, the majority of women are aware of its limitations after receiving genetic counseling. However, clinicians may need to consider alternative ways to communicate the limitations of NIPT to those women with less formal education to ensure understanding.

Keywords: noninvasive prenatal testing, patient perception of negative screening, negative noninvasive prenatal testing, prenatal screening for aneuploidy, limitations of prenatal screening, prenatal screening, genetic counseling

Background

Chromosomal aneuploidy is estimated to occur in 1/160 live births, the vast majority consisting of trisomy 21, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and sex chromosome conditions.1 Before the advent of recent prenatal testing options, women seeking information about aneuploidy in their pregnancy generally had two options: (1) invasive diagnostic testing that confers a risk for miscarriage or (2) noninvasive screening, which generally had false-positive rates of 5% or more and positive predictive values (PPVs) between 1 and 10%.2 3

In November 2011, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), or prenatal cell-free fetal DNA screening, became clinically available for use in high-risk populations. NIPT was validated in a high-risk population in multiple studies, all of which have shown similar accuracies for aneuploidy detection.4 5 6 7 The most recent meta-analysis by Gil et al in 2015 analyzed data from 37 relevant studies and determined that NIPT detection rates for the most common aneuploidies are approximately 99.2% for trisomy 21, 96.3% for trisomy 18, 91% for trisomy 13, and 90 to 93% for sex chromosome aneuploidy.8 While the detection rates and PPVs for NIPT are increased in comparison to other methods of prenatal screening, NIPT is not a diagnostic test, and a negative NIPT result does not guarantee a pregnancy is unaffected.9 NIPT laboratories' marketing efforts and Web site content often focus on the detection rate rather than PPV or residual risk.10 It is unclear whether the general patient population understands this distinction, which may have implications for downstream uptake of invasive testing and emotional preparation at birth.11 12 Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional study to assess patient understanding of the residual risk for trisomy 21, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and sex chromosome aneuploidy after receiving a negative NIPT result.

Methods

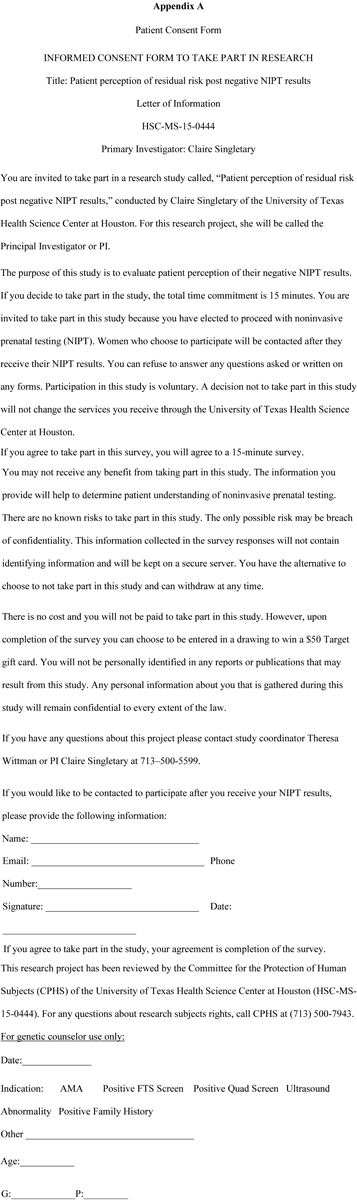

From August 1, 2015, through January 29, 2016, women who were at least 18 years old, English or Spanish speaking, and had been consented for NIPT during their genetic counseling appointment were invited to participate in the study. Only those women who had formal genetic counseling with a prenatal genetic counselor were recruited and consented. Participating centers were staffed by University of Texas Health and Baylor College of Medicine prenatal genetic counselors in the Houston, Texas, area and approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Texas Health and Memorial Hermann Hospital (HSC-MS-15–0444), Baylor College of Medicine and affiliated Texas Children's Hospital (H-37683), and the Harris Health System (15–09–1193). Those patients willing to take part signed a consent form agreeing to be contacted after their NIPT results were available (Appendix A), and only those with a negative result were contacted to participate. The recruited participants were given their NIPT results over the phone by a prenatal genetic counselor. It is standard protocol among the genetic counselors involved in the study to emphasize the limitations of NIPT during the consent process as well as at the time of the results disclosure, including that it is not diagnostic, there remains a residual risk, and it does not test for every genetic disorder. Physical copies of NIPT results were only given upon patient request.

The survey given to those participants with a negative NIPT result consisted of a section designed to assess patient understanding of the limitations of NIPT, a section to assess worry level for various conditions, a section regarding subsequent testing, and a section with demographic information (Appendix B). An online survey tool, Redcap, was used to securely administer the survey via email and collect the data. Those participants unable to complete the survey via email were called and given the survey over the telephone. Data from telephone calls were manually added to the Redcap dataset. Data were analyzed using STATA, (v.14.1, College Station, TX). Comparison of data between groups was evaluated using chi-square analysis, Fisher exact test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Mann–Whitney test where appropriate. Statistical significance was assumed at a Type I error rate of 5%.

Results

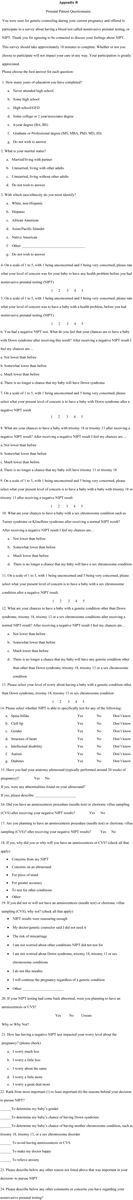

A total of 231 women agreed to be contacted for the survey. Six women were excluded due to either a positive NIPT result (n = 3) or failure to follow-through with the blood draw (n = 3). In total, 225 women were contacted after their negative NIPT result and asked to participate in the survey either through email or phone call. Twenty-nine women (13%) declined to participate after being contacted and 102 women (45%) were never successfully contacted, leaving a total of 94 participants (42%) from the original 225 consented. Twelve (13%) of the surveys were incomplete, the majority of which were missing the last several questions of the survey (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Survey completion flow diagram. NIPT, noninvasive prenatal testing.

The majority of participants (59%, n = 55) were referred to genetic counseling due to advanced maternal age and most identified as non-Hispanic white (36%, n = 34) or Hispanic (29%, n = 27). The majority of participants (64%, n = 60) reported having at least a 4-year college degree (Table 1).

Table 1. Participant demographics, n = 94.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 34 | 36 |

| Hispanic | 27 | 29 |

| African American | 16 | 17 |

| Asian | 11 | 12 |

| Other | 5 | 5 |

| No Answer | 1 | 1 |

| Household income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 10 | 11 |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 15 | 16 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 16 | 17 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 15 | 16 |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 20 | 21 |

| $150,000 or more | 12 | 13 |

| Do not wish to answer | 6 | 6 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school | 1 | 1 |

| High school/GED | 11 | 12 |

| Some college | 22 | 23 |

| 4-year degree | 32 | 34 |

| Graduate degree | 28 | 30 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 84 | 89 |

| Unmarried | 9 | 11 |

| Do not wish to answer | 1 | 1 |

| Age (y) | ||

| 21–29 | 15 | 16 |

| 30–34 | 15 | 16 |

| 35–39 | 54 | 57 |

| 40–43 | 10 | 11 |

| Indication | ||

| Advanced maternal age | 55 | 59 |

| Positive serum screen | 11 | 12 |

| Ultrasound abnormality | 11 | 12 |

| Low risk | 9 | 10 |

| Two or more indications | 8 | 9 |

Patient Perception of Residual Risk Post Negative NIPT Results

The majority of participants indicated their risk for aneuploidy was decreased but not eliminated post NIPT. A total of 61% (n = 57) of women indicated their risk to have a baby with Down syndrome was much lower, 55% (n = 52) indicated that their risk was much lower for trisomy 13/18, and 49% (n = 46) said that their risk to have a baby with a sex chromosome aneuploidy was much lower. A proportion of women also indicated that there was no residual risk after a negative NIPT. Specifically, 34 to 39% of participants indicated there was no longer a chance for their baby to have Down syndrome, trisomy 13/18, or a sex chromosome aneuploidy after receiving a negative NIPT result. Additionally, participants were asked to indicate their risk to have a baby with a genetic condition other than Down syndrome, trisomy 13/18, or sex chromosome aneuploidy after receiving a negative NIPT result. A total of 13% (n = 12) correctly answered that their risk was not lower than before, 29% (n = 27) indicated that there was no longer any chance for their baby to have any genetic problem, 49% (n = 46) answered that it was much lower than before, and 9% (n = 8) responded that it was somewhat lower than before. Women with less than a 4-year college education were significantly more likely to incorrectly respond that there was no longer a risk for their baby to have trisomy 13/18 (p = 0.012) or a sex chromosome abnormality (p = 0.039). Participants with less than a 4-year education also appeared to be more likely to indicate that there was no longer a chance for their baby to have Down syndrome; however, this did not reach significance (p = 0.086). Other demographic categories did not show a significant influence on patient perception of negative NIPT results (Table 2). This analysis was performed using Fisher exact test via STATA v. 14.1.

Table 2. Patient perception of risk post negative NIPT, n = 94.

| Down syndrome (%) | T13/T18 (%) | Sex chromosome aneuploidy (%) | Any other genetic condition (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of residual risk post negative NIPT | ||||

| Not lower than before | 0 | 1 | 5 | 13 |

| Somewhat lower than before | 5 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Much lower than before | 61 | 55 | 49 | 49 |

| No longer a chance | 34 | 34 | 39 | 29 |

| Demographic factors and risk perception post negative NIPT | ||||

| Ethnicitya | p = 0.440 | p = 0.119 | p = 0.177 | p = 0.130 |

| Incomeb | p = 0.588 | p = 0.540 | p = 0.166 | p = 0.752 |

| Educationc | p = 0.086 | p = 0.012 | p = 0.039 | p = 0.159 |

| Aged | p = 0.649 | p = 0.550 | p = 0.486 | p = 0.885 |

| Indicatione | p = 0.238 | p = 0.082 | p = 0.324 | p = 0.700 |

Abbreviations: NIPT, noninvasive prenatal testing; T18/T13, trisomy 13, trisomy 18.

Ethnicity: White Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, Other, do not wish to answer.

Income: <$25,000, $25,000–$49,999, $50,000–74,999, $75,000–$99,999, $100,000–$149,999, $150,000+, do not wish to answer.

Education: Some high school, high school graduate/GED, some college, 4-year degree, graduate degree.

Age: 21–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–43.

Indication: Advanced maternal age, positive serum screen, ultrasound abnormality, low risk, two or more indications.

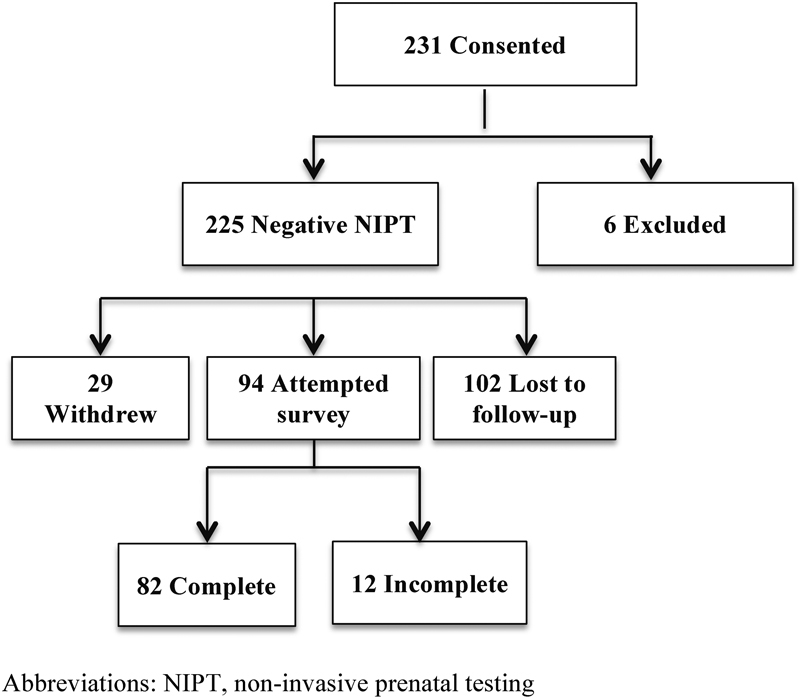

Most Important and Least Important Reasons for Pursuing NIPT

Participants were asked to share the most important and least important reasons for pursuing NIPT on a scale of 1 to 6, with 1 being the most important and 6 being the least important. There was no significant difference in how participants ranked their reasons for pursuing NIPT between the various demographic categories (ethnicity, p = 0.586; income, p = 0.747; education, p = 0.212; age, p = 0.373; indication, p = 0.123) (Fig. 2). This analysis was performed using Fisher exact test via STATA v. 14.1.

Fig. 2.

Most and least important reasons for pursuing NIPT (presented as percentages, n = 85).

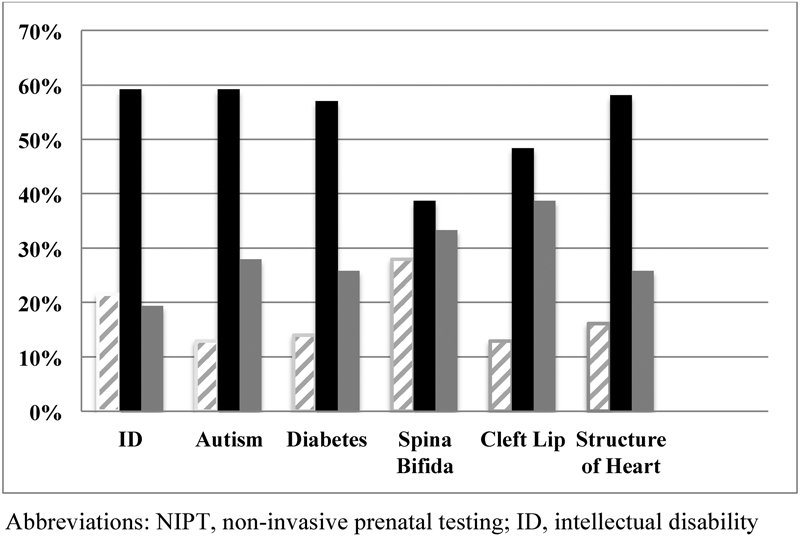

Patient Perception of Conditions Tested by NIPT

Participants were asked to indicate whether NIPT could test for the following: intellectual disability, autism, diabetes, spina bifida, cleft lip, gender, and structure of the heart. The vast majority of participants (92%, n = 86) were able to correctly identify that NIPT can test for gender. When looking at the remaining six items from this question, a participant had to indicate that NIPT did not test for the item to be scored as correct. Cleft lip, structure of heart, and spina bifida were considered structural abnormalities, while intellectual disability, autism, and diabetes were considered nonstructural. Those with less formal education were significantly less likely to answer correctly and had lower scores overall (p = 0.021). A total of 14% (5/36) of women with less formal education correctly answered all of the questions in comparison to 37% (22/60) of those women with at least 4 years of college. Overall, the participants were more likely to believe that NIPT could test for structural abnormalities (cleft lip, spina bifida, and structure of heart) versus nonstructural abnormalities (intellectual disability, autism, and diabetes) (p< 0.0005) and women with less than a 4-year degree were even more likely than those with higher education to believe that that NIPT could test for both structural abnormalities (p = 0.024) and nonstructural abnormalities (p = 0.010) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Patient perception of conditions tested by NIPT, n = 93. ID, intellectual disability; NIPT, noninvasive prenatal testing.

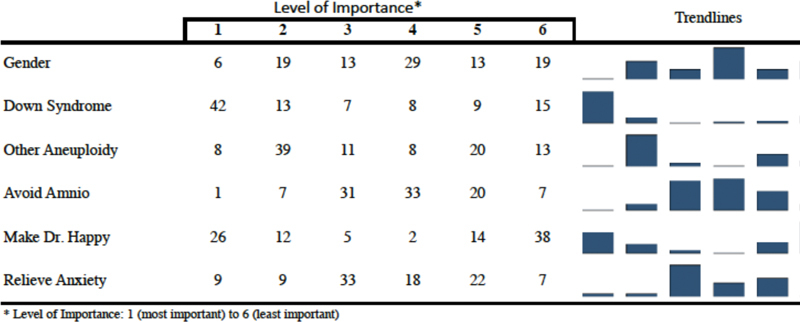

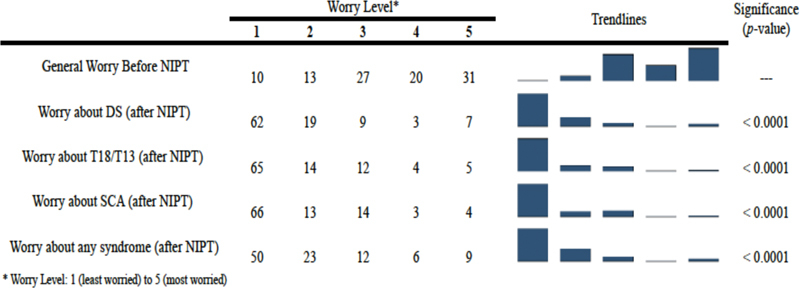

Worry Levels before and after Negative NIPT

Participants were asked to rank their general worry level about having a child with any health problem before undergoing NIPT and then their specific worry levels for Down syndrome, trisomy 13/18, and sex chromosome abnormality after testing via NIPT on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being unconcerned and 5 being very concerned. Similarly, women were asked what their level of concern was to have a baby with any genetic condition after a negative NIPT result. There was a significant decline when comparing the general level of worry before NIPT to each of the worry levels for Down syndrome (p < 0.0001), trisomy13/18 (p < 0.0001), sex chromosome aneuploidy (p < 0.0001), and any other genetic condition after a negative NIPT result (p < 0.0001). Despite the fact that NIPT cannot reduce risk for all genetic conditions, the majority of participants (n = 67, 70%) reported a decrease in worry to have a baby with any genetic disorder (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Worry levels before and after negative NIPT (%), n = 94. DS, Down syndrome; NIPT, noninvasive prenatal testing; SCA, sex chromosome aneuploidy; T18/T13, trisomy 13, trisomy 18.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess patient perception of the residual risk for Down syndrome, aneuploidy other than Down syndrome, birth defects, and other genetic conditions, after a negative NIPT. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine patient understanding of the limitations of NIPT. The cohort consisted of women who received formal genetic counseling from a prenatal genetic counselor and thus excluded women who received NIPT directly through their obstetrician. The data demonstrate that despite the relatively recent implementation of NIPT into obstetric practice, the majority of women who receive formal genetic counseling by genetic counselors are aware of its limitations. Overall, most participants were able to recognize that NIPT is a screening test and that it significantly reduces the risk for those conditions it tests for, but does not eliminate the risk entirely. Of note for practitioners, patient comprehension of NIPT's screening ability increased significantly with education level. Therefore, practitioners may need to spend additional time discussing the implications of NIPT with patients who have less formal education. Additionally, it should be noted that the genetic counselors involved in the recruitment of this study generally spent 45 to 60 minutes with patients, significantly more time than most obstetric appointments, thus allowing time for discussion and clarification of the limitations of NIPT.

Similarly, many women correctly recognized that NIPT does not test for nonstructural abnormalities such as autism, intellectual disability, and diabetes or structural abnormalities such as heart defects, cleft lip, and spina bifida. Interestingly, participants were more likely to incorrectly respond that NIPT could evaluate for structural abnormalities compared with the nonstructural abnormalities. It is unclear why patient comprehension differed by abnormality. Heart defects and cleft lip are often associated with aneuploidy; therefore, women may have falsely assumed that a negative NIPT reduced the risk for nonaneuploidy-associated heart defects and clefting. In addition, many women at our participating centers had an ultrasound following their genetic counseling appointment. Thus, they may have confused reassurance for structural conditions from the ultrasound with reassurance from NIPT. Furthermore, blood may be drawn to assess alpha fetal protein levels and spina bifida risk at the same time as blood is drawn for NIPT; thus, women may have falsely believed these tests are one in the same. Additional studies may wish to delve into the underlying reasons behind this misunderstanding.

This study also demonstrated that negative NIPT results significantly decreased worry levels of patients regarding having a baby with Down syndrome (p < 0.00001), trisomy 13/18 (p < 0.00001), and sex chromosome aneuploidy (p < 0.00001). This asserts the clinical utility of NIPT to provide appropriate reassurance for women who experience anxiety regarding their risk to have a baby with aneuploidy. However, this study also showed that women who undergo NIPT are also more likely to experience a false decrease in worry levels for conditions not screened by NIPT, suggesting that negative NIPT results may provide patients with false general reassurance in addition to appropriate reassurance for aneuploidy. It is unclear whether or not this is due to lack of understanding related to NIPT or general unfamiliarity with other genetic conditions.

Although the majority of women are likely to understand the limitations of NIPT after genetic counseling, it is clear that education level plays a role in comprehension. Women who had less than a four-year college education were more likely to believe that their NIPT could eliminate their risk to have a child with aneuploidy. Similarly, women with more education were more likely to understand what conditions were included in NIPT. These data are consistent with findings regarding traditional prenatal screening tests. Wong et al. in 2012 demonstrated that women with less formal education were more likely to perceive second trimester ultrasound as more sensitive and diagnostic.13 Moreover, past studies of maternal serum screening demonstrated that low health literacy and poor comprehension of the limitations of screening are associated with less years of formal education.14 15 Women with low health literacy may also have difficulty with numeracy, confounding their interpretation of the sensitivity, specificity, and PPVs of prenatal screening methods. In 2004, Gates et al examined the role of numeracy on patient understanding and concluded that women with lower levels of literacy and numeracy have the most difficulty in accurately interpreting information about risk.16 The effect of education and health literacy on patient understanding of prenatal screening is an important consideration, as approximately 40% of women 25 years and older in the United States do not have any formal education beyond high school.17

An additional issue that may confuse patients is the manner in which the 99% detection rate for NIPT is often highlighted by the media and laboratory testing materials rather than focusing on the individual patient's PPV and negative predictive value. Without sufficient background knowledge, women may get the impression that the PPV and detection rates are both 99%. A study by Mercer et al in 2014 examined the impact of the availability and use of the Internet for gathering information about NIPT.10 Their study showed a lack of comprehensiveness and quality of information regarding NIPT obtained through Internet sources. Moreover, many of the Web sites either failed to mention or downplayed information about the limitations and disadvantages of NIPT while simultaneously promoting the accuracy of the test without mentioning the importance of negative predictive value and PPV calculations. It is no wonder that women who research NIPT on the Internet may not appreciate the residual risk for aneuploidy, especially women without advanced formal education.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The incorporation of NIPT into obstetric practice has proved both exciting and overwhelming. Although it is clear that this new screening option can provide tremendous benefits to women worried about having a baby with a common aneuploidy, proper pretest genetic counseling is essential to ensure that patients are informed of the limitations and potential results from NIPT. This study demonstrated that NIPT invokes similar issues to previous prenatal screening modalities and that providers should be cognizant of the tendency for women with less formal education to overinflate the power of screening to decrease or eliminate their risk for a baby with a genetic condition. Genetic counselors and obstetricians must prioritize communicating information regarding NIPT accurately and clearly, so that women considering it as a screening option may be adequately informed. When possible, attention should be paid to a patient's education level and information should be tailored accordingly. The development of patient-friendly decision aids that clearly state the limitations of screening and what a negative test means may assist in residual risk communication, informed consent, and decision making.18

As this was a pilot study with a limited number of participants, more research is needed to examine patient perception of the limitations of NIPT and how this may vary based on patient demographic and geographic factors. Future studies may wish to examine whether the implementation of targeted educational materials and decision aids augment patient understanding of NIPT, especially as the testing platforms are expanded. Furthermore, research should be done to assess patient perception of positive NIPT results and whether or not women who screen positive accurately understand the implications and limitations of the results.

Limitations

This study was limited by the small sample size. The majority of women were referred for genetic counseling due to either advanced maternal age or positive serum screen. Therefore, we cannot confidently extrapolate to the low-risk population. In addition, 64% of participants had at least a 4-year college degree. Given the association of education level with understanding, a larger sample size might have allowed for parsing out subgroups from women who had less than a 4- year degree into those with some college, those with a high school diploma, and those without a high school diploma to further stratify the finding. Additionally, the survey used was carefully developed to evaluate the aims of this study; however, this assessment tool has not been validated in other studies. Finally, this research was limited to the greater Houston, Texas, area; thus, these results may not be generalizable to other geographical regions.

References

- 1.Driscoll D A, Gross S. Clinical practice. Prenatal screening for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2556–2562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wapner R, Thom E, Simpson J L. et al. First-trimester screening for trisomies 21 and 18. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1405–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Positive predictive value again. BJOG. 1999;106(9):vii–viii. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palomaki G E, Kloza E M, Lambert-Messerlian G M. et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: an international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182368a0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palomaki G E, Deciu C, Kloza E M. et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: an international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi D W, Platt L D, Goldberg J D, Abuhamad A Z, Sehnert A J, Rava R P. et al. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824fb482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gil M M, Quezada M S, Bregant B, Ferraro M, Nicolaides K H. Implementation of maternal blood cell-free DNA testing in early screening for aneuploidies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(1):34–40. doi: 10.1002/uog.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil M M, Quezada M S, Revello R, Akolekar R, Nicolaides K H. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for fetal aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(3):249–266. doi: 10.1002/uog.14791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neufeld-Kaiser W A, Cheng E Y, Liu Y J. Positive predictive value of non-invasive prenatal screening for fetal chromosome disorders using cell-free DNA in maternal serum: independent clinical experience of a tertiary referral center. BMC Med. 2015;13:129. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0374-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercer M B, Agatisa P K, Farrell R M. What patients are reading about noninvasive prenatal testing: an evaluation of Internet content and implications for patient-centered care. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(10):986–993. doi: 10.1002/pd.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiller G E, Kershberg H B, Goff J, Coffeen C, Liao W, Sehnert A J. Women's views and the impact of noninvasive prenatal testing on procedures in a managed care setting. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(5):428–433. doi: 10.1002/pd.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall S, Bobrow M, Marteau T M. Psychological consequences for parents of false negative results on prenatal screening for Down's syndrome: retrospective interview study. BMJ. 2000;320(7232):407–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong A E, Collingham J P, Koszut S P, Grobman W A. Maternal factors associated with misperceptions of the second-trimester sonogram. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(11):1029–1034. doi: 10.1002/pd.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goel V, Glazier R, Holzapfel S, Pugh P, Summers A. Evaluating patient's knowledge of maternal serum screening. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16(5):425–430. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199605)16:5<425::AID-PD874>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho R N, Plunkett B A, Wolf M S, Simon C E, Grobman W A. Health literacy and patient understanding of screening tests for aneuploidy and neural tube defects. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27(5):463–467. doi: 10.1002/pd.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gates E A. Communicating risk in prenatal genetic testing. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census Bureau Educational Attainment in the United States 2014. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data. Accessed February 18, 2016

- 18.Vlemmix F, Warendorf J K, Rosman A N. et al. Decision aids to improve informed decision-making in pregnancy care: a systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120(3):257–266. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]