Abstract

Introduction

Recent studies have indicated that patients are showing increased interest in playing a larger role in making decisions regarding their medical treatment. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disease that manifests either as Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD treatment is multifaceted and dependent on patient-specific factors. The selection of treatment options is mostly driven by physicians, and it is unclear to what degree patients are involved in shared decision-making (SDM). The objective of the current study is to assess preferences among Japanese patients with IBD in regard to SDM during their treatment for IBD.

Methods

A nationwide web-based survey was performed in Japan during February 2016. The patients were asked for their basic clinical characteristics, socioeconomic status, medical history, treatment details, and preferences regarding SDM in IBD treatment. Differences were analyzed by chi-square, t tests, a multiple regression analysis, and ordered logistic regression analysis.

Results

In response to the screening survey, a total of 1068 Japanese nationals met the inclusion criteria for this study of being patients diagnosed with IBD who are currently receiving treatment. Of these, 235 had CD and 800 UC; 33 were not specified. Overall, the majority of these patients felt that SDM was very important. Furthermore, interest in SDM was strongly associated with certain disease comorbidities, surgical history, and current treatment, although there were some differences in the results between CD and UC.

Conclusion

The present study found that the majority of IBD patients in Japan wanted to have a role in their treatment plan. The results indicate that the patient’s preference in regard to SDM was driven by their perception of the severity or progression of their disease.

Funding

Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Keywords: Gastroenterology, Inflammatory bowel disease, Japan, Shared decision making, Patient preferences

Introduction

Several recent studies indicate that patients in the US prefer to be involved in decisions concerning their treatment, and patient participation in these decisions improves compliance with the treatment regimen and the patient’s overall condition [1–5]. Other studies in Europe have shown similar results [6–9].

Shared decision-making (SDM) is defined as the process of interaction between patients who wish to be involved in making treatment decisions and their healthcare providers. Usually, the responsibility of informing and recommending treatment to patients lies with their healthcare providers, and it is only the process of deciding how to act on this information that is shared with the patients. With SDM, the goal is to enhance patient involvement, and, on the basis of the available evidence, facilitate “evidence-based patient choice” [10, 11]. SDM can therefore be used to educate patients about the utmost importance of adherence to medication and the necessity to commit and follow through on their treatment [12]. SDM has become even more important in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as new medications are developed, new side effects become known, and the risk-versus-benefit ratio becomes more difficult to interpret. IBD, which includes both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic inflammatory condition of the intestinal tract. There is no cure for either CD or UC, and these patients face numerous decisions regarding treatment of their disease [13]. Several therapeutic strategies, including the wide use of immunosuppressants, have been advocated in the treatment of CD and UC, each with its own risks and benefits [9, 14].

Given the variety of issues facing IBD patients and their providers, a number of studies have used survey methods to obtain information on a range of issues [14]. However, we have been unable to find any research work on SDM among Japanese IBD patients. Accordingly, it is unknown to what extent Japanese IBD patients actually want to be involved in decision-making regarding the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for their disease. Comprehending the situation of IBD patients’ preferences with regard to their involvement in the decision of treatment choices is of great importance in deciding on an appropriate treatment regimen.

The current study investigated the interest of Japanese IBD patients to have input in the selection of their course of treatment and compared how that interest varied based on patient characteristics.

Methods

Questionnaire

To identify Japanese IBD patients, a web-based screening survey was sent to more than 2,000,000 Japanese nationals registered in a consumer panel database where all persons registered in the database have opted into accept research surveys. Thus, informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the survey. Inclusion criteria for this study were patients with a self-reported IBD diagnosis who are currently receiving treatment.

Those respondents from the screening survey who met the inclusion criteria were asked for their basic clinical characteristics (diagnosis, age, and gender), socioeconomic status (marital status, household incomes, educational level, and work status), medical history (time since diagnosis, surgical history, and comorbidity), and treatment details (current treatment, type of hospital, and frequency of visits) in addition to the questionnaire regarding SDM.

We adapted the questionnaire developed by Baars et al. who surveyed preferences regarding SDM in Dutch IBD patients [9]. The original questionnaire (copyright© 2010 Karger Publishers, Basel, Switzerland) was translated into Japanese by two native Japanese speakers working independently. Quality and essence capture were then validated by reconciling the two translations into one questionnaire that was translated back into English by one native English speaker. A qualitative pilot test was conducted with six IBD patients who were asked whether it was easy to understand or whether it needed any changes in wording. We then performed a pilot online quantitative survey to collect responses from 50 IBD patients to make sure that the questionnaire was working and easy for patients to understand.

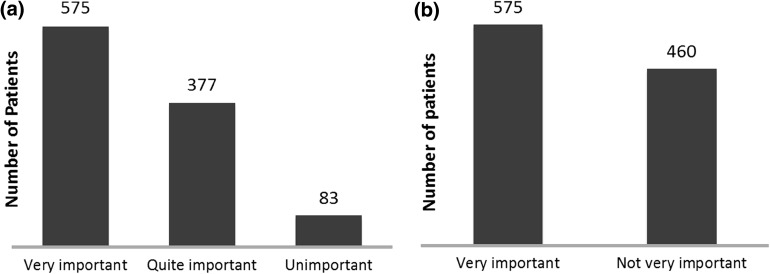

The pilot patients were asked to answer how important is it that the physician involves them in the decisions concerning their medical treatment. The answers were given on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from (a) very important, (b) quite important, (c) quite unimportant, and (d) totally unimportant. Only a small number of patients responded with quite unimportant (answer c) and totally unimportant (answer d), so we initially performed sensitivity analysis using three dimensions: “very important” (answer a), quite important (answer b), and unimportant (answers c and d). Then, to increase the power of the statistical analysis, we then reduced the categories down to two dimensions for the main analysis—very important (answer a) and not very important (answers b, c, and d).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the differences in the level of importance of SDM. Differences between UC and CD were analyzed by chi-square and t tests. The analysis of the association between the importance of SDM and the patients’ characteristics was conducted using a multiple regression analysis and an ordered logistic regression, and the results are reported as odds ratios (OR). The STATA 10 statistics package (College Station, TX, USA) was used for the analysis, and a value of P < 0.05 was defined as significant.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on a web-based survey and does not involve any interventions conducted on human subjects by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all patients to collect their personal information except for individual-specific information capable of identifying individuals.

Results

Patients

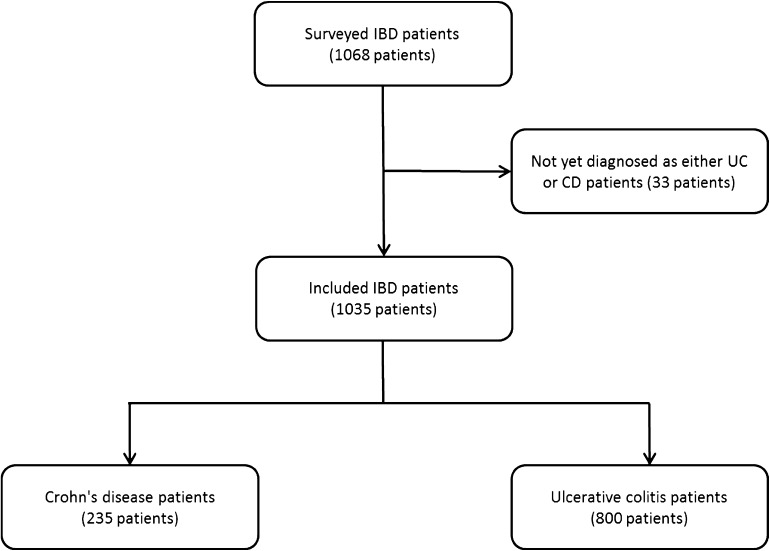

In response to the screening survey, a total of 1068 Japanese nationals met the inclusion criteria for this study, defined as patients diagnosed with IBD who are currently receiving treatment. Of these, 235 had CD and 800 UC; 33 were not specified and were therefore left out of the analysis (Fig. 1). According to data from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, the ratio of UC to CD in Japanese IBD patients is around 4:1 [15]. Thus, the sample used for this study can be considered reasonably representative of the relative weight of UC and CD patients in Japan.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow in this study. IBD inflammatory bowel disease, UC ulcerative colitis, CD Crohn’s disease

Overall, the majority of patients (56%) thought having a physician involve them in the decisions concerning their treatment was very important. The distribution of the patients’ preferences is shown in Fig. 2. The patients’ characteristics (Table 1) revealed that the majority of the IBD patients that responded to the questionnaire had UC (77%), with 23% having CD. The majority of patients in both groups were male, with CD having a higher percentage of males than UC. In addition, the majority of patients in both groups were >40 years, with a larger percentage with UC compared to CD. The majority of CD patients had a history of surgery (62%), and use of biologic agents in treatment was 48%. These proportions were higher than those in UC (12% and 8%, respectively). As for the time since diagnosis, 42% of CD patients had been diagnosed for >15 years compared to only 22% of UC patients.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the patients’ preferences regarding shared decision making; a patients’ preferences with three levels of discrimination and b patients’ preferences with two levels of discrimination

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall | CD | UC | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 1035 | 235 (23) | 800 (77) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 45.35 ± 10.74 | 42.27 ± 9.95 | 46.19 ± 10.83 | <0.001 |

| ≤40 years | 353 (34) | 102 (43) | 251 (31) | |

| 41–60 years | 590 (57) | 124 (53) | 466 (58) | |

| >60 years | 92 (9) | 9 (4) | 83 (11) | |

| Gender | 0.022 | |||

| Male | 675 (65) | 168 (71) | 507 (63) | |

| Female | 360 (35) | 67 (29) | 293 (37) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Single | 385 (37) | 124 (53) | 261 (33) | |

| Married | 650 (63) | 111 (47) | 539 (67) | |

| Highest education | 0.023 | |||

| College or less | 519 (50) | 136 (58) | 383 (48) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 447 (43) | 84 (36) | 363 (45) | |

| Master’s degree | 69 (7) | 15 (6) | 54 (7) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Full time | 580 (56) | 130 (55) | 450 (56) | 0.800 |

| Part time | 95 (9) | 19 (8) | 76 (10) | 0.509 |

| Self-employed | 79 (8) | 20 (9) | 59 (7) | 0.564 |

| Housewife | 127 (12) | 24 (10) | 103 (13) | 0.274 |

| Student | 5 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (0) | 0.355 |

| Unemployed/pensioners | 132 (13) | 38 (16) | 94 (12) | 0.074 |

| Others | 17 (2) | 2 (1) | 15 (2) | 0.873 |

| Household incomes | 0.911 | |||

| Less than 2 M JPY | 95 (9) | 23 (10) | 72 (9) | |

| 2–4 M JPY | 191 (18) | 47 (20) | 144 (18) | |

| 4–6 M JPY | 240 (23) | 55 (24) | 185 (23) | |

| 6–8 M JPY | 171 (17) | 36 (15) | 135 (17) | |

| 8–10 M JPY | 99 (10) | 24 (10) | 75 (9) | |

| More than 10 M JPY | 104 (10) | 19 (8) | 85 (11) | |

| Do not want to reveal | 135 (13) | 31 (13) | 104 (13) | |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 117 (11) | 34 (14) | 83 (10) | 0.081 |

| Hypertension | 146 (14) | 38 (16) | 108 (14) | 0.301 |

| COPD asthma | 41 (4) | 13 (6) | 28 (4) | 0.160 |

| Diabetes | 72 (7) | 16 (7) | 56 (7) | 0.919 |

| Depression | 65 (6) | 17 (7) | 48 (6) | 0.493 |

| OA and RA | 44 (5) | 12 (5) | 32 (4) | 0.460 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 64 (6) | 15 (6) | 49 (6) | 0.885 |

| Surgical history | ||||

| Yes | 240 (23) | 146 (62) | 94 (12) | <0.001 |

| Time since diagnosis | <0.001 | |||

| 0–2 years | 161 (16) | 27 (11) | 134 (17) | |

| 3–8 years | 361 (35) | 66 (28) | 296 (37) | |

| 9–15 years | 241 (23) | 44 (19) | 197 (25) | |

| >15 years | 272 (26) | 99 (42) | 173 (22) | |

| Current treatment | ||||

| Nutritional | 244 (24) | 137 (58) | 107 (13) | <0.001 |

| 5-ASA | 824 (79) | 168 (71) | 656 (82) | <0.001 |

| Steroid | 166 (16) | 39 (17) | 127 (16) | 0.791 |

| Immunosuppressant | 144 (14) | 53 (23) | 91 (11) | <0.001 |

| Biologic agents | 176 (17) | 113 (48) | 63 (8) | <0.001 |

| Cytapheresis | 17 (2) | 1 (0) | 16 (2) | 0.095 |

| Others | 70 (7) | 8 (3) | 62 (8) | 0.020 |

| Type of hospitals | <0.001 | |||

| University hospital | 252 (24) | 92 (39) | 160 (20) | |

| General/specialist hospital | 538 (52) | 128 (55) | 410 (51) | |

| Clinics | 244 (24) | 15 (6) | 229 (29) | |

| Others | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Frequency of visit | <0.001 | |||

| More than once in a month | 99 (9) | 38 (16) | 61 (8) | |

| Once every month | 354 (34) | 73 (31) | 281 (35) | |

| Once every 2 months | 341 (33) | 94 (40) | 247 (31) | |

| Once every 3 months | 172 (17) | 23 (10) | 149 (19) | |

| Less than every 3 months | 69 (7) | 7 (3) | 62 (8) | |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

CD Crohn’s disease, UC ulcerative colitis, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OA osteoarthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

Patient Preferences

The characteristics of the patients’ preferences are shown in Table 2. A multiple regression analysis was used to determine whether there were any differences between IBD patients who found it very important to share the decision-making and those who found it not very important based on their characteristics. The results (Table 2) demonstrated that there was no significant difference associated with the age of the patient, their gender, educational level, work status, household incomes, or time since diagnosis. However, there were significant differences between those patients that found it very important to be involved in the decision making concerning their treatment and those that did not concerning surgical history or various comorbidities, including dyslipidemia and COPD/asthma. Patients receiving a biologic agent significantly favored SDM in comparison to non-biologic users. Furthermore, the majority of patients treated at university hospitals (67%) favored SDM, as did married patients.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics: patients' preference, two levels

| Characteristics | Very important | Not very important | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 575 | 460 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 45.57 + 10.48 | 45.06 + 11.07 | 0.866 |

| ≤40 years | 193 (33) | 160 (35) | |

| 41–60 years | 332 (57) | 258 (56) | |

| >60 years | 50 (10) | 42 (9) | |

| Gender | 0.358 | ||

| Male | 368 (64) | 307 (67) | |

| Female | 207 (36) | 153 (33) | |

| Marital status | 0.307 | ||

| Single | 206 (36) | 179 (39) | |

| Married | 369 (64) | 281 (61) | |

| Highest education | 0.170 | ||

| College or less | 303 (53) | 216 (47) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 234 (41) | 213 (46) | |

| Master’s degree | 38 (6) | 31 (7) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Full time | 319 (55) | 261 (57) | 0.685 |

| Part time | 51 (9) | 44 (9) | 0.700 |

| Self-employed | 94 (6) | 45 (10) | 0.020 |

| Housewife | 79 (14) | 48 (10) | 0.107 |

| Student | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.841 |

| Unemployed/pensioners | 80 (13) | 52 (11) | 0.211 |

| Others | 9 (2) | 8 (2) | 0.812 |

| Household incomes | 0.404 | ||

| Less than 2 M JPY | 53 (9) | 42 (9) | |

| 2–4 M JPY | 114 (20) | 77 (17) | |

| 4–6 M JPY | 127 (22) | 113 (25) | |

| 6–8 M JPY | 96 (17) | 75 (16) | |

| 8–10 M JPY | 47 (8) | 52 (11) | |

| More than 10 M JPY | 64 (11) | 40 (9) | |

| Do not want to reveal | 74 (13) | 61 (13) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 81 (14) | 36 (8) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 89 (15) | 57 (12) | 0.156 |

| COPD asthma | 34 (5) | 7 (2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 44 (8) | 28 (6) | 0.325 |

| Depression | 44 (8) | 21 (5) | 0.042 |

| OA and RA | 32 (6) | 12 (3) | 0.019 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 41 (7) | 23 (5) | 0.157 |

| Surgical history | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 164 (28) | 76 (16) | |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.167 | ||

| 0–2 years | 98 (17) | 63 (14) | |

| 3–8 years | 190 (33) | 171 (37) | |

| 9–15 years | 127 (22) | 114 (25) | |

| >15 years | 160 (28) | 112 (24) | |

| Current treatment | |||

| Nutritional | 162 (28) | 82 (18) | <0.001 |

| 5-ASA | 449 (78) | 375 (81) | 0.173 |

| Steroid | 108 (18) | 58 (13) | 0.007 |

| Immunosuppressant | 88 (15) | 56 (12) | 0.148 |

| Biologic agents | 123 (21) | 53 (12) | <0.001 |

| Cytapheresis | 13 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.080 |

| Others | 39 (7) | 31 (7) | 0.978 |

| Type of hospitals | 0.053 | ||

| University hospital | 170 (29) | 82 (18) | |

| General/specialist hospital | 287 (50) | 251 (55) | |

| Clinics | 117 (21) | 127 (27) | |

| Others | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Frequency of visit | 0.028 | ||

| More than once a month | 69 (12) | 30 (7) | |

| Once every month | 190 (33) | 164 (36) | |

| Once every 2 months | 189 (33) | 152 (33) | |

| Once every 3 months | 95 (16) | 77 (17) | |

| Less than every 3 months | 32 (6) | 37 (7) | |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OA osteoarthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

There were some differences between CD and UC patients regarding the factors affecting the preference for SDM (Table 3). Factors affecting UC patients were marital status, diabetes, surgical history, biologic treatment, and type of hospital; in comparison, preferences in CD patients were affected only by type of hospitals.

Table 3.

Factors affecting Japanese patients’ preference regarding SDM

| Characteristics | Overall [ORs (95% CI)] | CD [ORs (95% CI)] | UC [ORs (95% CI)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (reference ≤40 years) | |||

| 41–60 years | 1.26 (0.92–1.73) | 1.62 (0.72–3.62) | 1.24 (0.87–1.78) |

| >60 years | 1.00 (0.56–1.80) | 0.52 (0.06–4.24) | 1.05 (0.55–1.99) |

| Gender (reference male) | |||

| Female | 1.17 (0.82–1.68) | 1.12 (0.39–3.19) | 1.21 (0.81–1.82) |

| Marital status (reference single) | |||

| Married | 1.40 (1.00–1.92) | 1.45 (0.61–3.43) | 1.48 (1.01–2.17) |

| Highest education (reference college or less) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.79 (0.59–1.06) | 0.72 (0.32–1.66) | 0.73 (0.53–1.02) |

| Master’s degree | 1.07 (0.61–1.89) | 0.94 (0.20–4.39) | 1.07 (0.56–2.02) |

| Occupation | |||

| Full time | 1.38 (0.47–4.01) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.97 (0.30–4.39) |

| Part time | 1.13 (0.36–3.50) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.65 (0.19–2.26) |

| Self-employed | 0.72 (0.23–2.27) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.62 (0.17–2.20) |

| Housewife | 1.56 (0.50–4.86) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.99 (0.29–3.44) |

| Student | 1.56 (0.16–14.72) | 0 (Omitted) | 0 (Omitted) |

| Unemployed/pensioners | 1.70 (0.56–5.15) | 0 (Omitted) | 1.28 (0.37–4.39) |

| Household incomes (reference less than 2 M JPY) | |||

| 2–4 M JPY | 1.41 (0.48–4.12) | 0 (Omitted) | 1.00 (0.31–3.26) |

| 4–6 M JPY | 1.13 (0.37–3.56) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.66 (0.19–2.31) |

| 6–8 M JPY | 0.73 (0.23–2.31) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.63 (0.18–2.27) |

| 8–10 M JPY | 1.58 (0.50–4.97) | 0 (Omitted) | 1.01 (0.29–3.54) |

| More than 10 M JPY | 1.59 (0.17–15.10) | 0 (Omitted) | 0 (Omitted) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.82 (1.08–3.08) | 0.73 (0.10–5.08) | 1.66 (0.93–2.98) |

| Hypertension | 0.95 (0.61–1.49) | 2.65 (0.47–15.09) | 0.83 (0.50–1.36) |

| COPD asthma | 3.61 (1.41–9.26) | 0 (Omitted) | 2.26 (0.83–6.17) |

| Diabetes | 0.59 (0.32–1.10) | 0 (Omitted) | 0.44 (0.22–0.88) |

| Depression | 1.64 (0.91–2.96) | 1.10 (0.21–5.74) | 1.69 (0.87–3.30) |

| OA and RA | 0.61 (0.12–3.16) | 0 (Omitted) | 1.00 (0.16–6.27) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 0.68 (0.34–1.34) | 0.11 (0.01–1.24) | 0.82 (0.39–1.75) |

| Surgical history | |||

| Previous surgical | 1.66 (1.13–2.42) | 1.49 (0.67–3.31) | 1.94 (1.12–3.36) |

| Time since diagnosis (reference 0–2 years) | |||

| 3–8 years | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | 0.54 (0.09–3.21) | 0.75 (0.46–1.18) |

| 9–15 years | 0.67 (0.42–1.07) | 0.30 (0.05–1.93) | 0.78 (0.47–1.29) |

| >15 years | 0.79 (0.49–1.27) | 0.93 (0.15–5.56) | 0.71 (0.42–1.20) |

| Current treatment | |||

| Nutritional | 1.20 (0.82–1.75) | 1.50 (0.69–3.26) | 1.12 (0.66–1.91) |

| 5-ASA | 1.08 (0.72–1.63) | 1.25 (0.53–2.99) | 1.01 (0.60–1.72) |

| Steroid | 1.40 (0.95–2.09) | 4.20 (0.98–17.98) | 1.18 (0.75–1.84) |

| Immunosuppressant | 0.93 (0.62–1.41) | 0.64 (0.28–1.48) | 1.09 (0.65–1.82) |

| Biologic agents | 1.76 (1.17–2.65) | 1.81 (0.78–4.23) | 1.89 (1.02–3.50) |

| Cytapheresis | 1.61 (0.44–5.85) | 0 (Omitted) | 1.82 (0.49–6.78) |

| Type of hospitals (reference university hospital) | |||

| General/specialist hospital | 0.64 (0.46–0.90) | 1.06 (0.48–2.33) | 0.52 (0.35–0.78) |

| Clinics | 0.61 (0.40–0.92) | 0.12 (0.02–0.57) | 0.61 (0.38–0.97) |

| Frequency of visits (reference more than once in a month) | |||

| Once every month | 0.85 (0.49–1.48) | 0.65 (0.16–2.66) | 1.02 (0.53–1.96) |

| Once every 2 months | 0.90 (0.51–1.60) | 0.62 (0.15–2.56) | 1.09 (0.55–2.18) |

| Once every 3 months | 1.06 (0.57–2.00) | 0.36 (0.69–1.92) | 1.41 (0.68–2.94) |

| Less than every 3 months | 0.62 (0.30–1.30) | 0.13 (0.01–1.91) | 0.86 (0.36–2.01) |

CD Crohn’s disease, UC ulcerative colitis, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OA osteoarthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

Bold values indicate significance at 5% level or higher

The sensitivity analysis conducted with three levels of preference showed similar results to the main analysis with two levels (data not shown).

Discussion

This is the first large survey to demonstrate that Japanese IBD patients prefer to be involved in the decision-making process regarding their treatment. Japanese patients have traditionally allowed their physician to have absolute authority over their treatment [1]. However, the internet has provided Japanese patients easier access to medical information and medical education. Such internet access has been shown to allow patients to play a greater role in decision-making concerning treatment in other countries [5, 6, 16]. The current study referred to and applied a questionnaire developed for a study in The Netherlands. This study found that the majority of Dutch IBD patients wanted to play an active role in the decisions regarding their treatment [9]. The current study evaluated the importance of SDM to Japanese IBD patients; the results indicate that a majority of these patients felt that it is very important that they share in the determination of their treatment modality. Furthermore, an analysis of the importance of these preferences shows that they are strongly associated with certain disease comorbidities, surgical history, and the patients’ current treatment, along with their disease state.

A previous study among eight Asian countries excluding Japan suggested that surgical history is associated with severe UC disease stage, although this is not the case in CD where disease progression is non-linear [17]. However, the association between surgical history and the preference regarding SDM in the total study population for this current study might be driven by the UC patients’ preference, since a significant proportion of the patients sampled in this study had UC (77%). The results of the sensitivity analysis support this hypothesis (data not shown).

In addition, many patients from this survey have other comorbidities such as dyslipidemia and COPD/asthma. Keely et al. reported pulmonary intestinal cross-talk between mucosal inflammatory diseases and IBD. They discussed the possibility of common risk factors, such as smoking and genetics, as well as epithelial barrier dysfunction and inflammation, as common characteristics of both conditions [18].

Further, Koutroumpakis et al. reported an association between long-term lipid profiles and IBD disease severity [19]. Dyslipidemia is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease; however, their large cohort study suggested IBD patients had less frequent incidence of high total cholesterol and high LDL cholesterol and more frequent incidence of low HDL and high triglycerides in comparison to the general population. This is consistent with the current survey results and the association with disease severity.

Multimorbidity is associated with a significantly worse quality of life in the general population. The current survey results find that patients with dyslipidemia or COPD/asthma with moderate IBD favor SDM. Furthermore, there is a strong association between the importance of SDM and patients treated at university hospitals. Since physicians at university hospitals tend to be the leading experts in their field, the increased importance of SDM among patients being treated at university hospitals might be related to greater severity of the disease in such patients as well as for the stronger need to control comorbidities. The current survey results also show a difference between CD and UC patients regarding SDM. There are fewer factors associated with SDM in CD patients than in UC patients. The majority of CD patients have a surgical history and a lengthy time since diagnosis, have used or are currently using biologics agents, and are being treated at university hospitals, suggesting that they might spend more time communicating with their physician about the treatment compared to UC patients.

The use of biologic agents to treat IBD is also associated with the severity of the disease state [20]. Another finding is the proportion of patients in current treatment with relatively severe disease. This survey’s results suggest that the majority of CD patients have severe disease. Furthermore, a review of current treatment approaches of patients in this study provides insights into the severity of the disease and suggests that patients with more severe disease in this study might be the majority in CD patients, which, in turn, might be a factor in the difference between CD and UC patients regarding SDM.

These findings are not consistent with those from some previous studies. A recent study of young patients from Japan and the US found that both populations favored patient-centered care for less serious disease conditions [1]. Additional research suggests that Japanese patients prefer not to be involved in decision-making if it involves a life-threatening condition, such as cancer [21, 22].

Married patients also show a strong preference for SDM in comparison to unmarried patients. This is not consistent with a study by Dronkers et al. that found unmarried head-and-neck cancer patients also favored an active role in their treatment [23]. However, Forsythe et al. found married long-term cancer patients were more likely to want to participate in the decision-making regarding treatment [24]. These differences might be associated with the role of family support or participation in the decision-making process. Thus, for married IBD patients, the spouse and family members might play an important role in the decision-making process in regard to treatment.

The results from current study of Japanese patients with IBD indicate that the majority of patients want to have an active role in their treatment plan. There is no association between the patients’ preference for SDM and their age, gender, education level, or socioeconomic status. Instead, the importance of SDM appears to be associated with their marital status, treatment at university hospitals, their general health condition, and comorbidities. In addition, patients with a surgical history and those treated with biologic agents also favor SDM.

Based on the findings of the Baars et al. study, patients in The Netherlands appear to play a more aggressive role in the decision-making than that played by Japanese patients in the current study [9]. This might be due to differences in the physicians’ availability for consultation in the two countries, as consultation time with Japanese physicians tends to be quite limited.

The difference might also be due to the broader availability of biologic agents in The Netherlands. The first biologic agent was approved for use for CD in Japan in the early 2000s and after 2010 for UC, and for several years, use of biologics was confined to a limited number of leading hospitals. The current study shows that Japanese patients treated at university hospitals want to be more involved in their treatment decisions in comparison to patients who visited clinics or general hospitals. As well as the possible impact of disease severity, current treatment regimens that include biologics might be an underlying factor in this regard.

Limitations

Since data for the study were collected using a web-based questionnaire, all data are based on self-assessment from the patient respondents, which can affect data reliability. In addition, although patients’ disease severity has been inferred from the data, no questions related specifically to disease severity were included. Finally, although the study demonstrated that patient involvement in SDM is desired by respondents, it did not address the specifics of the type and nature of involvement that is desired.

Conclusions

Results from the present study found that the majority of IBD patients in Japan want a role in their treatment plan. The results also indicate that the patient’s preference in regard to SDM is driven by their perception of the severity or progression of their disease. The results of our study also showed that preferences in regard to SDM in Japanese IBD patients were similar to Dutch IBD patients.

Acknowledgements

This study, article processing charges, and open access fee were funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical KK. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. Special thanks go to Miina Waratani, Izumi Kato, Jia Li, and Yukiko Morimoto at Ipsos Healthcare Japan, Ltd., for their assistance with data collection and analysis. We also want to thank to J. Ludovic Croxford and Steve Johnson for proof reading and editing the manuscript.

Disclosures

Ryuji Morishige is an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K and has nothing to disclose. Hiroshi Nakajima is an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K and has nothing to disclose. Kazutake Yoshizawa is an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K and has nothing to disclose. Jörg Mahlich is an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K and has nothing to disclose. Rosarin Sruamsiri is an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K and has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on a web-based survey and does not involve any interventions conducted on human subjects by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all patients to collect their personal information except for individual-specific information capable of identifying individuals.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/0417F060299D0B42.

References

- 1.Alden DLMM, Akashi J. Young adult preferences for physician decision-making style in Japan and the United States. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012;24(1):173–184. doi: 10.1177/1010539510365098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D, Nichol MB, Eton D, Nelson JB, Mulani P. Estimating clinically meaningful changes for the functional assessment of cancer therapy—prostate: results from a clinical trial of patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;12(1):124–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan CM, Ahmad WA. Differences in physician attitudes towards patient-centredness: across four medical specialties. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degner LFSJ, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn KE, Smith MA, Vanness D. A typology of preferences for participation in healthcare decision making. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2006;63(5):1158–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giordano A, Mattarozzi K, Pucci E, et al. Participation in medical decision-making: attitudes of Italians with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;275(1–2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Donnell M, Hunskaar S. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision-making generally and in hormone replacement and urinary incontinence treatment decision-making specifically. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Donnell M, Hunskaar S. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision-making among Norwegian women with urinary incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(11):1370–1376. doi: 10.1080/00016340701622310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baars JE, Markus T, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Patients’ preferences regarding shared decision-making in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from a patient-empowerment study. Digestion. 2010;81(2):113–119. doi: 10.1159/000253862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel CA. Shared decision making in inflammatory bowel disease: helping patients understand the tradeoffs between treatment options. Gut. 2012;61(3):459–465. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel CA, Lofland JH, Naim A, et al. Gastroenterologists’ views of shared decision making for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(9):2636–2645. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3675-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollard SBN, Bryan S. Physician attitudes toward shared decision making: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(9):1046–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alatri A, Schoepfer A, Fournier N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for venous thromboembolic complications in the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(10):1200–1205. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1185464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bewtra M, Johnson FR. Assessing patient preferences for treatment options and process of care in inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review of quantitative data. Patient. 2013;6(4):241–255. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0031-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report 2013–2014 Contents. Intractable disease measures, number of intractable disease medical treatment recipient certificates issued [accessed 2016 October 6]. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw8/dl/02e.pdf.

- 16.Gattellari M, Ward JE. Measuring men’s preferences for involvement in medical care: getting the question right. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(3):237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng SC, Zeng Z, Niewiadomski O, et al. Early course of inflammatory bowel disease in a population-based inception cohort study from 8 countries in Asia and Australia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):86–95.e3; quiz e13–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Keely S, Talley NJ, Hansbro PM. Pulmonary-intestinal cross-talk in mucosal inflammatory disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5(1):7–18. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koutroumpakis E, Ramos-Rivers C, Regueiro M, et al. Association between long-term lipid profiles and disease severity in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(3):865–871. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3932-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, Straumann A, Rogler G, Schoepfer AM. Prevalence and risk factors for therapy escalation in ulcerative colitis in the Swiss IBD Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(6):1348–1358. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields CG, Morrow GR, Griggs J, et al. Decision-making role preferences of patients receiving adjuvant cancer treatment: a university of Rochester cancer center community clinical oncology program. Support Cancer Therapy. 2004;1(2):119–126. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2004.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dronkers EA, Mes SW, Wieringa MH, van der Schroeff MP, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. Noncompliance to guidelines in head and neck cancer treatment; associated factors for both patient and physician. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:515. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1523-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Kent EE, et al. Social support, self-efficacy for decision-making, and follow-up care use in long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23(7):788–796. doi: 10.1002/pon.3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.