Abstract

Vincristine is a chemotherapeutic agent that is a component of many combination regimens for a variety of malignancies, including several common pediatric tumors. Vincristine treatment is limited by a progressive sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy (VIPN) is particularly challenging to detect and monitor in pediatric patients, in whom the side effect can diminish long term quality of life. This review summarizes the current state of knowledge regarding VIPN, focusing on its description, assessment, prediction, prevention, and treatment. Significant progress has been made in our knowledge about VIPN incidence and progression, and tools have been developed that enable clinicians to reliably measure VIPN in pediatric patients. Despite these successes, little progress has been made in identifying clinically useful predictors of VIPN or in developing effective approaches for VIPN prevention or treatment in either pediatric or adult patients. Further research is needed to predict, prevent, and treat VIPN to maximize therapeutic benefit and avoid unnecessary toxicity from vincristine treatment.

Keywords: Vincristine, peripheral neuropathy, prevention, assessment, pharmacogenetics, pediatric oncology

Introduction

The vinca alkaloids are a class of agents originally derived from the Madagascar periwinkle plant and historically utilized in diabetic patients for their presumed hypoglycemic effects. In the late 1950’s, it was realized that certain vinca alkaloids caused bone marrow suppression in mice as well as prolongation of life in rats with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [1]. Subsequently, this class of anti-mitotic agents has become extensively incorporated into multi-agent chemotherapy regimens for a vast number of malignancies including ALL, lymphomas, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, and kidney, liver, lung, brain and breast tumors amongst others. Additionally, immunosuppressant effects have led to their use in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Vincristine, the most commonly used vinca alkaloid in pediatric patients, frequently has dose-limiting neurotoxicity which can be devastating; not only leading to severe motor and sensory peripheral neuropathies affecting quality of life, but also contributing to treatment delays and dose reductions. This review will focus on describing vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy (VIPN), and summarizing the available literature around assessing, predicting and treating this adverse effect in pediatric patients.

Clinical use

Vinblastine (VBL) and vincristine (VCR) were the first two vinca alkaloid compounds to be successfully incorporated into chemotherapy regimens. These agents work by arresting dividing cells in metaphase by binding to the β-subunit of tubulin heterodimers to prevent polymerization and incorporation into microtubules [2]. In more recent decades, vindesine and vinorelbine have come to market as semi-synthetic vinca alkaloids. Vindesine has similar antitumor activity as vincristine, but increased myelosuppression and lack of clear improvement in neuropathic adverse events has limited its clinical usefulness [3]. Vinorelbine, on the other hand, is composed of an eight-member catharnine ring, as opposed to the nine-member rings of the other vinca alkaloids, which allows for increased capacity to bind to mitotic spindles over axonal microtubules, leading to decreased neurotoxicity with this agent [4]. Vinorelbine is most commonly used to treat breast and non-small cell lung cancers and myelosuppression is its dose-limiting side effect. Finally, vincristine has most recently been encapsulated in sphingomyelin and cholesterol nanoparticles as a vincristine sulfate liposome injection (VSLI) and marketed under the trade name Marqibo. This new formulation of vincristine was designed to allow for optimized pharmacokinetics, enhanced drug delivery to tumor tissues, and to allow for dose intensification [5]. It was FDA-approved in 2012 for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia-chromosome negative acute lymphoid leukemia.

Vincristine has poor oral bioavailability and is formulated for intravenous administration as vincristine sulfate. Vincristine sulfate is a vesicant and is fatal if given intrathecally. After intravenous administration, vincristine rapidly distributes extensively into most body tissues; however, there is poor penetration across the blood brain barrier (BBB) and into the central nervous system (CNS). The liver is primarily responsible for the metabolism of vincristine, which is a substrate for the cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) enzyme system, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, making it susceptible to drug-drug interactions and interpatient variability in metabolism [6,7]. Dosing adjustments should be made in the presence of hyperbilirubinemia, particularly elevated direct bilirubin. Vincristine has a long terminal half-life of 85 hours and is primarily eliminated in the feces. Vincristine is rarely myelosuppressive and can often be administered even in the presence of leukopenia and thrombocytopenia [8].

Description of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy (VIPN)

Peripheral neuropathy is a well-known side effect of several classes of chemotherapy including the vincas, taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel), and platins (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin). As described previously, the vincas (and taxanes) target the β-tubulin subunit of microtubules, which are critical components of nerve fiber axons. Due to the affinity of the vincas for both mitotic spindles and axonal microtubules, particularly with vincristine, these agents cause axonopathy that manifests as a slowly progressive axonal sensorimotor neuropathy [9,10]. Several additional mechanisms for vinca-induced peripheral neuropathy (VIPN) have been proposed from mechanistic work in cellular and animal models [11,12] and the exact mechanism is still not completely understood.

VIPN is experienced by nearly all children who receive vincristine treatment [13-15]. The incidence and severity varies based on a variety of risk factors, as described in section 5. Signs and symptoms of VIPN generally fall into three main categories: sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy [14,16-18]. Common characteristics of sensory neuropathy include numbness, tingling, and neuropathic pain experienced bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities. In most cases, VIPN progresses distally to proximally; signs and symptoms often first appear in the toes and feet, and as neuropathy worsens, clinical abnormalities become evident more proximally within the foot, ankle, and leg, followed by the fingers and hands. Children who receive vincristine become less able to detect light touch, pinprick sensations, vibration, and differences in temperature when hot or cold objects are applied to the skin. Although less common, some patients report hoarseness and jaw pain due to vincristine’s damaging effects on cranial nerves. Hyporeflexia, loss or reduction in deep tendon reflexes, provides evidence of both sensory and motor VIPN. Common motor neuropathy signs and symptoms include foot-drop and upper and lower extremity weakness. Indicators of autonomic neuropathy include constipation, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension [19,20].

When evaluating VIPN patterns over time, several interesting findings become evident. In the first year of vincristine therapy for ALL, hyporeflexia is the most common and severe VIPN manifestation, followed by decreased vibration sensibility and strength [14]. Signs and/or symptoms can emerge within a week of initiating vincristine therapy and continue to worsen even after vincristine dosing and frequency is decreased, known as the coasting effect [14]. VIPN severity can remain unchanged for up to 12 months following dose reduction [14], and can persist for years beyond treatment completion [15].

Assessment

Although peripheral neuropathy is a well-recognized side effect of vincristine therapy, VIPN characteristics, severity and incidence patterns, and the long-term consequences of VIPN on function and quality of life (QOL) in children are not well-understood. This dearth of knowledge is directly linked to the lack of widely-accepted, comprehensive, reliable, valid, and clinically feasible VIPN assessment approaches for use in pediatric populations. What follows is a brief overview of VIPN assessment techniques, and the benefits and challenges associated with their use (see Table 1).

Table 1.

| Test | Nerve Fiber Evaluated | Procedure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Tendon Reflexes | Large | Reflexes are graded on a scale from 0 (normal) to 4 (all reflexes absent). | The test can be conducted quickly and with children <5 years of age. | Some children may elicit a “fake” reflex response by moving their leg or ankle on their own. |

| Test using a reflex hammer with the child’s limbs relaxed. Test bilateral Achilles, patellar, brachioradialis, bicep, and tricep tendon reflexes. | The child may have trouble sitting still and relaxed during the test. | |||

| Requires clinician training and practice to increase testing accuracy. | ||||

| Strength | Large | Strength is scored from 0 (normal) to 4 (paralysis). | The child may enjoy proving his/her strength. | It may be difficult for the clinician to objectively score diminished strength. |

| While sitting on an exam table or on the edge of the bed, the child is asked to: | The test is time-consuming and difficult to conduct in very young children. | |||

| • Curl their toes downward and resist clinician attempts to uncurl their toes. | ||||

| • Flex the foot upwards and resist clinician attempts to push the foot down. | ||||

| • Push down on the clinician’s hand with their foot as if the hand is a gas/brake pedal, and resist clinician attempts to push the foot up. | ||||

| • Raise the leg (with knee bent) and resist clinician attempts to push the leg down. | ||||

| • Make a fist and resist clinician attempts to bend their wrists while the clinician pushes up and down on the fist. | ||||

| • Grip two of the clinician’s fingers with their hands and resist clinician attempts to pull their fingers out of the child’s grip. | ||||

| • Flex both arms/biceps and to resist clinician attempts to extend (un-flex) the arms. | ||||

| • Hold both arms out to the side (like wings) and resist clinician attempts to push the arms back down to the child’s sides. | ||||

| Vibration sensation | Large | Strike a 128 Hz tuning fork with the palm of the hand and place the tip to the bony surface of the great toe bilaterally. Ask the child tell when the “buzzing” or “vibration” has stopped. Perform this test bilaterally and move from distal to proximal areas if no vibration is felt. | The test requires minimal clinician training. | The test requires that children be continually re-focused on the vibration sensation. |

| Children enjoy the testing. | Young children may not be able to communicate precisely when the vibration stops. | |||

| Semmes-Weinstein Monofilaments (Pressure) | Large | Ask the child to close their eyes. Place the smallest filament at different locations on each hand and foot for a couple seconds each time. Ask the child to state when they feel the filament touch their skin. Vary the sites and speed of the test so that the child cannot predict the next location. If the child cannot detect the smallest filament after two attempts, the next-largest filament is used. | Objective measure that can evaluate large nerve fiber function. | The test is time-consuming, difficult to conduct in very young children, and requires specialized equipment (monofilaments) and clinician training. |

| Touch | Large | With the child’s eyes closed, brush a cotton ball across the skin in different areas on all extremities. Ask the child to state whether they can feel the cotton ball and where it is being applied. Perform this test bilaterally and move from distal to proximal areas if sensation is reduced. | A non-painful measure of large nerve fiber function. | The test is time-consuming. |

| Children enjoy the testing. | ||||

| Proprioception | Large | These tests evaluate balance and coordination. Tests that can be used include the finger-to-nose test, thumb-to-finger test, up/down test, and the Romberg test. | A non-painful measure that can evaluate large nerve fiber function. | It may be difficult to explain the procedure to a child. |

| Children enjoy the testing. | ||||

| Nerve Conduction Studies | Large | Evaluates nerve impulse transmission following electrical stimuli. | Can provide objective information about nerve conduction amplitude and velocity. | The tests are expensive, inconvenient (requires a neurologist referral), and uncomfortable for the child. |

| Pin-prick Sensation | Small | Ask the child to describe what if feels like when a sharp object (e.g. pin, neuro-tip) is placed on their skin. Perform this test on all extremities. The sensation should be one of pain rather than pressure. Perform this test bilaterally and move from distal to proximal areas if sensation is reduced. | An objective measure that can evaluate small fiber function. | The test is time-consuming and uncomfortable for the child. |

| Temperature sensation | Small | Use a cool object, such as a metal tuning fork, and place on the child’s skin, ask if they feel it as “cold”. Perform this test bilaterally and move from distal to proximal areas if sensation is reduced. | The test is quick and easy to conduct and not painful for the child. | It may be difficult for young children to differentiate variations in temperature sensation. |

Note. Modified from “Evaluation and Management of Peripheral Neuropathy in Diabetic Patients With Cancer”, by C. Visovsky, R.R. Meyer, J. Roller, and M. Poppas, 2008, Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12,p. 245. doi:10.1188/08.CJON.243-247. Copyright 2008 by Oncology Nursing Society. Adapted with permission.

There are several measurement tools that can be used to assess peripheral neuropathy in adults receiving neurotoxic drugs [21-24], and in children with neuropathy secondary to other diseases such as diabetes [25-29]. However, there are few VIPN measurement tools that have been optimized for use in pediatric oncology settings [14,16,30,31]. Grading scales, such as the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), are commonly used to provide a numeric score reflecting sensory and motor neuropathy severity [14]. When using these scales, a score of “0” reflects no neuropathy and a score of “5” equates to death caused by neurotoxicity. Although the NCI-CTCAE and other similar grading scales are familiar to clinicians and easy to use, several studies provide compelling evidence that these scales are marginally reliable, valid, sensitive, and responsive to change over time [16,32-35]. For example, Gilchrist et al. reported that NCI-CTCAE scores fail to detect 40% and 15% of sensory and motor neuropathy deficits, respectively.

Since vincristine damages both small and large nerve fibers involved with sensory, motor, and autonomic function [17], the best measurement approach should incorporate objective and subjective assessments that quantify damage to both fiber types [22,23,32]. Vincristine causes abnormally diminished sensory and motor nerve conduction amplitude, with motor nerves showing the most significant changes [15,18,36]. Objective measures should be used to uncover pre-clinical signs of earlyonset neuropathy that cannot be detected by the patient. When evaluating large nerve fiber function, oncology clinicians typically focus on assessing deep tendon reflexes and strength. Reflex assessment is the most feasible approach because it is quick to complete and can usually be conducted even with very young children. Testing the patient’s ability to feel vibration, pressure, and light touch, proprioception and nerve conduction amplitude and velocity tests (assessed via nerve conduction studies) also provide objective information about large nerve fiber function [15,18,37,38]. However, nerve conduction studies are not recommended for routine VIPN monitoring in children because the testing is painful. Pin-prick sensation testing is an objective assessment method that is sometimes used to evaluate small fiber function, but the testing procedure is time-consuming and uncomfortable. As an alternative, testing the child’s temperature sensibility-the ability to detect “cold” when a cold object, such as a metal tuning fork, is placed on the skin-is an efficient and non-painful objective approach for assessing small fiber function.

Regarding composite measures, the results of two studies provide evidence that the pediatric modified-Total Neuropathy Scale© (peds-mTNS©) has strong psychometric properties [16,31]. The peds-mTNS© was modified from the original Total Neuropathy Scale© (TNS©)-a composite measure that has been extensively tested in adult oncology populations and found to be reliable, valid, sensitive and responsive. [32,35,39-42]. The peds-mTNS© has three items that quantify subjective sensory, motor, and autonomic symptom severity. This tool also provides a rubric for scoring several objective VIPN measures (light touch, pin and vibration sensation, strength, and deep tendon reflexes). The ped-mTNS© has been shown to be reliable when used to measure VIPN in children ages 5-18 (Cronbach’s α = 0.76; inter-rater and intra-rater reliability correlations >0.9) [31]. The measure is also valid based on its ability to discriminate between control subjects and those with cancer (P<0.001), and demonstrates statistically significant score correlations with balance (spearman correlation (rs) = -0.626; P<0.001) and manual dexterity measures (rs = -0.461; P<0.001). Furthermore, it can detect subtle differences in VIPN severity as demonstrated by its lack of floor and ceiling effects [31].

The revised Total Neuropathy Score©-Pediatric Vincristine (TNS©-PV) is another TNS© variant that has been tested for use in children receiving vincristine [30]. The 5-item TNS©-PV quantifies subjective numbness, tingling, and neuropathic pain. Objective assessments are used to quantify vibration sensibility and deep tendon reflexes. This tool is valid for use in pediatric populations receiving vincristine based on moderately strong and statistically significant score correlations with cumulative vincristine dosage (r = 0.53; P<0.01), pharmacokinetic parameters (r = 0.41; P<0.05), and the NCI-CTCAE and Balis grading scale scores (r = 0.46-0.52; P<0.01). Additionally, the TNS©-PV is internally reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), responsive to change over time, and feasible for use in children ≥6 years of age. When compared with the ped-mTNS©, the TNS©-PV is more abbreviated. With practice, clinicians can complete the TNS©-PV assessment in five to ten minutes, depending on the child’s ability to cooperate.

In addition to objective assessment, it is also important to ask children and/or their caregivers to provide subjective ratings of VIPN symptom severity. Subjective ratings provide information about both small and large nerve fiber function, and inform clinicians about the patient’s perceptions of numbness, tingling, neuropathic pain in the upper and lower extremities, jaw pain, hoarseness, and constipation. Functional tests can be used to assess ankle range of motion [43], balance [44], lower extremity and grip strength [43], gross and fine motor development [43,45,46] and overall fitness [43]. Questionnaires can be used to assess painful VIPN [30,47] and effects on QOL [43]. Valid and reliable measures should also be used to evaluate VIPN-associated psychological sequela and cognitive impairment in long-term pediatric cancer survivors. However, it is important to note that many tests and questionnaires used to quantify VIPN-associated outcomes have not been comprehensively validated in pediatric oncology populations. Moreover, complex motor function and fitness tests, although used as outcomes measures in research studies, are impractical for monitoring VIPN in clinical settings due to the time, staff training, and equipment needed to conduct the testing.

In conclusion, it is important that pediatric clinicians monitor the short- and long-term consequences of vincristine treatment. Psychometrically strong and clinically feasible VIPN assessment tools, such as the TNS©-PV, are useful for quantifying VIPN signs and symptoms. However, other types of validated neuropathy assessment tools are still needed to assess long-term VIPN-associated outcomes such as pain and psychological symptoms, functional and cognitive disability, and impaired QOL. Lastly, given that routine VIPN assessment does not always occur in busy clinical settings, future research is needed to address VIPN assessment implementation barriers and to identify the best approach for translating evidence-based VIPN assessment approaches into practice.

Risk factors for VIPN

Treatment-related factors

Some treatment-related risk factors have been reported to partially explain the heterogeneous onset and severity of VIPN (Table 2). It is well established in adults that peripheral neuropathy, across drug-related causes, is a cumulative toxicity that increases with continued treatment [48]. Higher single doses increase the occurrence of VIPN early in therapy [49] and throughout treatment [50], thus providing the rationale for a maximum vincristine dose of 2 mg [51]. However, the effect of dose is less well established in pediatric patients, in whom cumulative vincristine dose does not appear to be associated with motor neuropathy severity [52]. Similarly, greater vincristine drug concentrations, or pharmacokinetics, have been associated with increased neuropathy in adults [53] but not pediatric patients [54,55].

Table 2.

Treatment- and Patient-related Predictors of Vincristine-Induced Neuropathy in Pediatric Patients

| Category | Predictor | Supporting Evidence | Vincristine Treatment Recommendations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-Related Factors | Higher Dose | Stronger evidence in adults but less established in pediatrics | Maximum 2 mg dose | [52] |

| Higher drug concentration | Stronger evidence in adults but less established in pediatrics | None | [54,55] | |

| Concomitant Azole Antifungals | Many case reports and some epidemiological studies | Avoid concomitant use | [56-58] | |

| Patient-Related Factors | Race | Higher occurrence in Caucasians than African-Americans in analyses of clinical trials | None | [60,61] |

| Age | Higher occurrence in older children and adults in analyses of clinical trials | None | [60,64] | |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease | Many case reports and some epidemiological studies | Contraindicated | [70-72] | |

| Guillain-Barre Syndrome | Some case reports | None | [74,75,100] | |

| Patient genetics | Significant hits from candidate (CYP3A5*3) and genome-wide (CEP72) pharmacogenetic studies | None | [60,76] |

Despite the lack of direct evidence of an association between drug concentration and peripheral neuropathy, particularly in pediatric patients, there is strong evidence that concomitant treatment with interacting medications, particularly azole antifungals, increases VIPN. A review of case reports identified 47 cases of patients treated concomitantly with azole antifungals (itraconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole) who experienced vincristine toxicity [56]. Direct comparisons of pediatric patients found that during concomitant treatment there is an increase in vincristine-induced toxicity [57,58]. Though no pharmacokinetic data is available, the assumed mechanism for this interaction is inhibition of CYP3A by azole antinfugals, leading to increased vincristine concentrations and enhanced VIPN. Further support for this mechanism is provided by the differences in toxicity occurrence and severity across azoles, with relatively small increases in toxicity seen with fluconazole, a weaker CYP3A inhibitor than the other azoles. An increase in VIPN in patients receiving concomitant aprepitant, another CYP3A4 inhibitor, further supports this mechanism [49]. However, it is possible that the azole antifungals themselves are neurotoxic and that the interaction is due to additive toxicity, not a pharmacokinetic interaction. Indeed, peripheral neuropathy has been reported in patients receiving long-term antifungal treatment in the absence of neuropathic chemotherapy, with the relative occurrence of neuropathy across antifungals similar to the patterns identified in the drug interaction studies [59]. Regardless of the mechanism, given the many case reports and comparative analyses, concomitant treatment with CYP3A4 inhibitors, particularly the azole antifungals, should be avoided in patients receiving vincristine treatment.

Patient-related factors

There is a great deal of interest in discovering patient-specific predictors of VIPN to guide individualized treatment that optimizes therapeutic outcomes. Several studies have reported that Caucasian patients have greater incidence and severity of VIPN than African-American patients [60,61]. This is particularly interesting given the opposite association with race has been reported for paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy [62,63]. Increased age has also been associated with increased risk of VIPN in adult [49] and pediatric [14,60,64] patients. This is unlikely to be due to vincristine pharmacokinetics [54,65], as drug concentrations are lower in older children than younger children due to the 2 mg dosing limit [66]. Finally, though deficiencies in vitamin B12 and other micronutrients are associated with neurotoxicity in the general population [67], vitamin levels are not meaningfully different in patients who do and do not experience VIPN [68].

There is overwhelming evidence that patients with the hereditary neuropathy condition Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) Disease are highly sensitive to VIPN. Retrospective testing of patients who developed severe neuropathy during vincristine treatment have found high rates of CMT [69] and many case reports have been published in the literature [70-72]. A family history of CMT should be considered a contraindication to vincristine treatment. Treatment substitution with the pharmacologically similar, but possibly less neurotoxic, vindesine has been reported to be successful [73]. Although there are fewer case reports, a very severe peripheral neuropathy leading to quadriparesis has been reported in patients with Guillain-Barre Syndrome treated with vincristine [74,75].

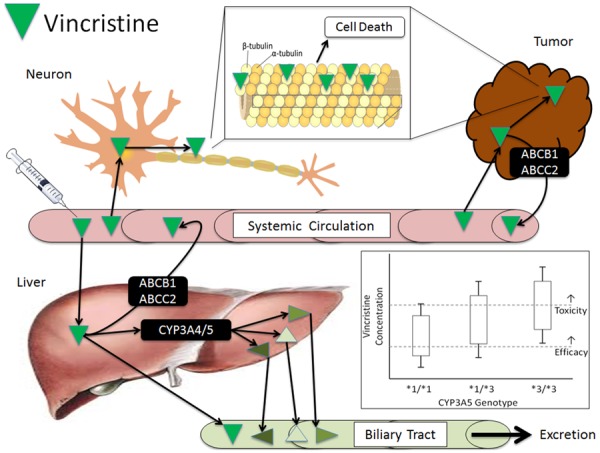

Aside from the strong genetic effect of CMT, there is particular interest in discovering common genetic polymorphisms that are predictive of VIPN (Table 3). Based on the importance of CYP3A5 in vincristine metabolism, Egbelakin et al. conducted a pharmacogenetic-pharmacokinetic-VIPN analysis focusing on the non-expresser CYP3A5*3 (rs776746) genotype [76]. In 107 pediatric ALL patients there was an increase in VIPN occurrence, severity, and duration, and more dose reductions and omissions in patients who were homozygous for CYP3A5*3. Patients who expressed CYP3A5 also had greater metabolite levels 1-hour after dosing, and there was a significant inverse association between metabolite levels and neuropathy severity. This provides compelling evidence that decreased vincristine metabolism in CYP3A5 non-expresser patients increases VIPN (Figure 1). This would also explain the inter-race difference in VIPN mentioned earlier, as the proportion of African Americans who express CYP3A5 is far higher than Caucasians (approximately 60% vs. 20%) [77]. However, as with other candidate pharmacogenetic associations, successful replication has been extremely challenging. Multiple independent studies in pediatric patients have not identified associations between CYP3A5*3 and drug concentrations [65] or VIPN [64,78,79].

Table 3.

Pharmacogenetic Associations with Vincristine-Induced Neuropathy in Pediatric Cancer Patients

| Reference | N | Age | Location and Race | Cancer Type | Vincristine Dose and Schedule | Genes and SNPs Analyzed | Neuropathy Phenotype | Pharmacogenetic Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartman Leukemia Research 2010 [79] | 34 | 4-12 | Netherlands | ALL | 2.0 mg/m2 × 31-34 cycles | CYP3A5*3, ABCB1*2, MAPT haplotype | Percentile score on Movement Assessment of Battery for Children 1 year after treatment completion | No associations |

| Egbelakin Pediatric Blood Cancer 2011 [76] | 107 | 1-18 | United States, 98% Caucasian | preB ALL | 1.5 mg/m2 weekly followed by a year of maintenance | CYP3A5*3 | Grade of neuropathy | CYP3A5*3 (non-expresser) had greater neuropathy occurrence and severity |

| Guilhaumou Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2011 [64] | 26 | 2-16 | France | Various | 1.5 mg/m2 weekly × 3 cycles | CYP3A4*1B, CYP3A5*3, ABCB1*2 | 3+ Global Toxicity Score (sum of pain, peripheral neuropathy, and GI toxicity grades) | No associations |

| Diouf Jama 2015 [60] | 321 | 0-19 | United States, 65% Genetically European | ALL | 1.5 or 2.0 mg/m2 weekly followed by a year of maintenance | 1,091,393 SNPs imputed from genome-wide association | Grade 2-4 peripheral neuropathy | CEP72 (rs924607) associated with increased neuropathy risk and severity |

| Gutierrez-Camino Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 2015 [81] | 142 | NR | Spain | B-ALL | 1.5 mg/m2 weekly × 4 cycles | CEP72 (rs924607) | Grade 2+ peripheral neuropathy | No association |

| Ceppi Pharmacogenomics 2015 [78] | 320 | NR | Canada, 98% French-Canadian | ALL | 1.5 mg/m2 weekly × 4 doses followed by 2 mg/m2 Q3W for 100 weeks | 17 SNPs in TUBB1, MAP4, ACTG1, CAPG, ABCB1, CYP3A5 | Grade 1-2 or 3-4 peripheral neuropathy | Hypothesis generating associations with ACTG1, CAPG, and ABCB1 |

Abbreviations: ALL: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, NR: Not Reported, SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Figure 1.

Vincristine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Vincristine enters the systemic circulation through direct intravenous administration. It is distributed via passive diffusion into organs for metabolism (liver), efficacy (tumor) and toxicity (neuronal cells). Vincristine is a substrate of several efflux transporters including ABCB1 (P-gp) and ABCC2, ABCC3, and ABCC10, which return vincristine to the circulation. In the tumor and neuron vincristine binds to the β subunit of tubulin, causing cellular apoptosis. In the liver vincristine is partially metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 to three inactive metabolites, followed by biliary excretion. The inset box and whisker plot is a hypothetical representation of relative systemic vincristine concentrations in patients stratified by their CYP3A5*3 (non-expresser) status. Patients heterozygous (*1/*3) or homozygous (*3/*3) for the non-expresser genotype would have greater systemic concentrations, causing more of these patients to have toxic levels of vincristine.

Several studies have also analyzed SNPs in ABCB1, the gene that encodes for the highly promiscuous p-glycoprotein transporter responsible for efflux of many cancer agents. There are three polymorphisms in ABCB1 (1236C>T, 2677G>T(A), 3435C>T) that comprise the *2 haplotype. These polymorphisms have been reported, but not validated, to be associated with many treatment-related outcomes in cancer patients. Individual studies have reported marginal decreases in vincristine elimination [80] while others have found no association with pharmacokinetics [65] or VIPN [64,65,78,79]. Alternatively, a nominal association was reported for a different SNP in the ABCB1 promoter (rs4728709) for which there was evidence of a protective effect, and two other SNPs in ACTG1 (rs1135989) and CAPG (rs2229668, rs3770102). However, these initial discoveries in a single retrospective analysis without appropriate statistical correction should be viewed skeptically until successful independent replication is reported [78].

In addition to these candidate gene approaches, Diouf et al. recently reported results of a genome-wide association study of VIPN in 321 pediatric patients receiving long-term continuation treatment for ALL on prospective clinical trials [60]. Analysis of more than 500,000 SNPs identified a single SNP in the promoter region of CEP72 that increased VIPN occurrence and decreased the cumulative dose at VIPN onset. The investigators provided mechanistic support for this finding by verifying that the promoter SNP decreases CEP72 expression, and that decreased CEP72 expression increases neuronal cell sensitivity to vincristine in vitro. Interestingly, this variant is less common in African-American (Minor Allele Frequency = 10%) than Caucasian (MAF = 40%) individuals, providing a second plausible explanation for the inter-race difference in VIPN. Despite the well-conducted pharmacogenetic analysis and intriguing mechanistic work, this finding also requires independent replication prior to prospective clinical translation. One initial attempt did not detect any association with VIPN in 142 pediatric patients receiving induction therapy for B-cell ALL [81], perhaps due to the different treatment settings.

Prevention & treatment

Multiple trials, primarily in adults, have sought to determine if medications can be given concomitantly with chemotherapy to prevent and/or treat VIPN. Unfortunately, the result of these efforts have been largely disappointing. The majority of trials suffered from limitations such as insufficient sample size or power, high dropout rate, variation in primary outcomes limiting comparability, and early trial termination [82]. Additionally, these trials occurred in a variety of treatment settings with various chemotherapy regimens, including combinations with other neuropathic agents, making interpretation and extrapolation a major challenge. The American Society of Clinical Oncology published a clinical practice guideline in 2014 reviewing the available literature, their bottom line recommendation was that no agent currently demonstrated consistent evidence to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Regarding interventions for established CIPN, duloxetine is the only drug with demonstrated efficacy for paclitaxel-or oxaliplatin-induced painful CIPN [82].

Specifically, agents such as venlafaxine, amifostine, glutamine, amitriptyline, Org 2766, electrolytes and vitamins were studied for CIPN prevention. Out of these, only amitriptyline and Org 2766 were looked at in patients receiving vinca alkaloids. Amitriptyline was evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 114 patients who were initiating therapy with a vinca, platinum, or taxane. There was no difference in neuropathic symptoms between groups and dry mouth and tremor were more severe in the amitriptyline cohort [83]. Org 2766 is a synthetic ACTH compound that has been shown to modulate VIPN in a snail model; however in a placebo-controlled clinical trial of 150 vincristine-treated patients, no difference was reported in neuropathy-free interval between treatment groups [84,85]. Venlafaxine and amifostine have both been independently studied for their ability to prevent platinum-induced peripheral neuropathy. Although beneficial effects have been recorded for both agents, more investigation is needed to verify that either is effective for preventing VIPN [86-91].

Similarly, demonstration of effectiveness in the treatment of existing neuropathy has been extremely challenging. Duloxetine has shown the most promise for the treatment of CIPN, demonstrating reduced pain scores compared to placebo in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study of 231 patients, however vincas were not included in this trial [92]. Gabapentin, an agent frequently given adjunctively to treat CIPN, was studied in a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study in 115 patients receiving vincas, platinums and taxanes. Symptom severity was similar between the patients who received gabapentin versus placebo and therefore this trial failed to demonstrate a benefit to the addition of gabapentin [93]. The proposed mechanism for efficacy of gabapentin in CIPN is related to its binding to the alpha-2-delta type-1 (α2δ-1) subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, which displays increased expression in certain peripheral neuropathy models [94]. Interestingly, in animal models, exposure to vincristine did not affect the level of α2δ-1 mRNA in either the dorsal spinal cord or the dorsal root ganglia, although paclitaxel and oxaliplatin did. In this study, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin-induced mechanical allodynia was responsive to oral doses of gabapentin, whereas vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy was not [95], possibly explaining the results seen in the randomized controlled trial in humans. Finally, lamotrigine was also shown not to be beneficial in patients receiving chemotherapy [96].

More recently, clinicians have looked to alternative therapies to prevent and treat CIPN. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 208 patients receiving multiple neurotoxic chemotherapy agents including vinca alkaloids, platinums, taxanes or thalidomide a topical compounded preparation containing amitriptyline, ketamine and baclofen was shown to improve CIPN symptoms. Patients identified decreased tingling, cramping, and burning pain of the hands as well as improvement in the patients’ ability to hold a pen and write [97]. Similar trials of topical menthol and capsaicin are ongoing [82]. Finally, there is some evidence that physical therapy improves ankle and knee strength as well as range of motion in children with ALL [98]. Despite the widespread interest and numbers of clinical trials looking to prevent and treat chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, no clear standard has been determined or can be recommended at this time.

Conclusion

In summary, vincristine is an antineoplastic agent that is widely incorporated into multi-agent chemotherapy regimens to treat a variety of malignancies. Dose-limiting sensorimotor neuropathy presents a challenge to clinicians, particularly in the treatment of pediatric patients. Reliable and sensitive composite measures for detecting VIPN onset and progression in pediatric patients have been developed and validated, but are not uniformly integrated into clinical practice. Despite avoidance of vincristine administration concomitantly with interacting drugs, and in patients with genetic predispositions to neuropathic conditions, a large number of patients still develop VIPN. Pharmacogenetic associations with VIPN risk have been reported, however, few of the promising candidates have been successfully replicated and none have been translated into clinical practice. Although a variety of agents have been studied for VIPN prevention and/or treatment, they have not been proven effective. Moving forward, it is critical that VIPN measurement is standardized so that studies can be conducted to identify high-risk patients and to evaluate novel preventative and therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP Jr. The Vinca Alkaloids: a New Class of Oncolytic Agents. Cancer Res. 1963;23:1390–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:790–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joel S. The comparative clinical pharmacology of vincristine and vindesine: does vindesine offer any advantage in clinical use? Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;21:513–525. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory RK, Smith IE. Vinorelbine--a clinical review. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1907–1913. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman JA, Deitcher SR. Marqibo(R) (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saba N, Bhuyan R, Nandy SK, Seal A. Differential Interactions of Cytochrome P450 3A5 and 3A4 with Chemotherapeutic Agent-Vincristine: A Comparative Molecular Dynamics Study. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2015;15:475–483. doi: 10.2174/1871520615666150129213510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennison JB, Kulanthaivel P, Barbuch RJ, Renbarger JL, Ehlhardt WJ, Hall SD. Selective metabolism of vincristine in vitro by CYP3A5. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1317–1327. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahmani R, Zhou XJ. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of vinca alkaloids. Cancer Surv. 1993;17:269–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobert S, Vulevic B, Correia JJ. Interaction of vinca alkaloids with tubulin: a comparison of vinblastine, vincristine, and vinorelbine. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6806–6814. doi: 10.1021/bi953037i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legha SS. Vincristine neurotoxicity. Pathophysiology and management. Med Toxicol. 1986;1:421–427. doi: 10.1007/BF03259853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carozzi VA, Canta A, Chiorazzi A. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: What do we know about mechanisms? Neurosci Lett. 2015;596:90–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyette-Davis JA, Walters ET, Dougherty PM. Mechanisms involved in the development of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Pain Manag. 2015;5:285–296. doi: 10.2217/pmt.15.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toopchizadeh V, Barzegar M, Rezamand A, Feiz A. Electrophysiological consequences of vincristine contained chemotherapy in children: A cohort study. J Pediatr Neurol. 2009;7:351–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavoie Smith EM, Li L, Chiang C, Thomas K, Hutchinson RJ, Wells EM, Ho RH, Skiles J, Chakraborty A, Bridges CM, Renbarger J. Patterns and severity of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2015;20:37–46. doi: 10.1111/jns.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramchandren S, Leonard M, Mody RJ, Donohue JE, Moyer J, Hutchinson R, Gurney JG. Peripheral neuropathy in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2009;14:184–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilchrist LS, Marais L, Tanner L. Comparison of two chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy measurement approaches in children. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausheer FH, Schilsky RL, Bain S, Berghorn EJ, Lieberman F. Diagnosis, management, and evaluation of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:15–49. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtemanche H, Magot A, Ollivier Y, Rialland F, Leclair-Visonneau L, Fayet G, Camdessanche JP, Pereon Y. Vincristine-induced neuropathy: Atypical electrophysiological patterns in children. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:981–985. doi: 10.1002/mus.24647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argyriou A, Polychronopoulos P, Koutras A, Iconomou G, Gourzis P, Assimakopoulos K, Kalofonos H, Chroni E. Is advanced age associated with increased incidence and severity of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0868-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomber S, Dewan P, Chhonker D. Vincristine induced neurotoxicity in cancer patients. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:97–100. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavoie Smith EM, Barton DL, Qin R, Steen PD, Aaronson NK, Loprinzi CL. Assessing patient-reported peripheral neuropathy: the reliability and validity of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-CIPN20 Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2787–2799. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberti P, Rossi E, Cornblath DR, Merkies IS, Postma TJ, Frigeni B, Bruna J, Velasco R, Argyriou AA, Kalofonos HP, Psimaras D, Ricard D, Pace A, Galie E, Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Faber CG, Lalisang RI, Boogerd W, Brandsma D, Koeppen S, Hense J, Storey D, Kerrigan S, Schenone A, Fabbri S, Valsecchi MG, Cavaletti G CI-PeriNomS Group. Physician-assessed and patient-reported outcome measures in chemotherapy-induced sensory peripheral neurotoxicity: two sides of the same coin. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:257–264. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F, Mattavelli L, Susani E, Alberti P, Cortinovis D, Bidoli P. Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neurotoxicity assessment: a critical revision of the currently available tools. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:479–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calhoun EA, Welshman EE, Chang CH, Lurain JR, Fishman DA, Hunt TL, Cella D. Psychometric evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity (Fact/GOG-Ntx) questionnaire for patients receiving systemic chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:741–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns J, Menezes M, Finkel RS, Estilow T, Moroni I, Pagliano E, Laura M, Muntoni F, Herrmann DN, Eichinger K, Shy R, Pareyson D, Reilly MM, Shy ME. Transitioning outcome measures: relationship between the CMTPedS and CMTNSv2 in children, adolescents, and young adults with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2013;18:177–180. doi: 10.1111/jns5.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns J, Ouvrier R, Estilow T, Shy R, Laura M, Pallant JF, Lek M, Muntoni F, Reilly MM, Pareyson D, Acsadi G, Shy ME, Finkel RS. Validation of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease pediatric scale as an outcome measure of disability. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:642–652. doi: 10.1002/ana.23572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pagliano E, Moroni I, Baranello G, Magro A, Marchi A, Bulgheroni S, Ferrarin M, Pareyson D. Outcome measures for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: clinical and neurofunctional assessment in children. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirschfeld G, von Glischinski M, Blankenburg M, Zernikow B. Screening for peripheral neuropathies in children with diabetes: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1324–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isikay S, Isikay N, Kocamaz H, Hizli S. Peripheral neuropathy electrophysiological screening in children with celiac disease. Arq Gastroenterol. 2015;52:134–138. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032015000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavoie Smith EM, Li L, Hutchinson RJ, Ho R, Burnette WB, Wells E, Bridges C, Renbarger J. Measuring vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E49–60. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318299ad23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist LS, Tanner L. The pediatric-modified total neuropathy score: a reliable and valid measure of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with non-CNS cancers. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:847–856. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith KA, Merkies IS, Hill EE, Cornblath DR. Measures of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review of psychometric properties. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010;15:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frigeni B, Piatti M, Lanzani F, Alberti P, Villa P, Zanna C, Ceracchi M, Ildebrando M, Cavaletti G. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity can be misdiagnosed by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity scale. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16:228–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postma TJ, Heimans JJ, Muller MJ, Ossenkoppele GJ, Vermorken JB, Aaronson NK. Pitfalls in grading severity of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:739–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1008344507482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavoie Smith EM, Cohen JA, Pett MA, Beck SL. The validity of neuropathy and neuropathic pain measures in patients with cancer receiving taxanes and platinums. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:133–142. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain P, Gulati S, Seth R, Bakhshi S, Toteja GS, Pandey RM. Vincristine-induced neuropathy in childhood ALL (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) survivors: prevalence and electrophysiological characteristics. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:932–937. doi: 10.1177/0883073813491829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vainionpaa L, Kovala T, Tolonen U, Lanning M. Vincristine therapy for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia impairs conduction in the entire peripheral nerve. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(95)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vinik AI, Nevoret ML, Casellini C, Parson H. Diabetic neuropathy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42:747–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith EM, Cohen JA, Pett MA, Beck SL. The reliability and validity of a modified total neuropathy score-reduced and neuropathic pain severity items when used to measure chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients receiving taxanes and platinums. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:173–183. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c989a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F, Piatti M, Rota S, Briani C, Zara G, Plasmati R, Pastorelli F, Caraceni A, Pace A, Manicone M, Lissoni A, Colombo N, Bianchi G, Zanna C Italian NETox Group. The Total Neuropathy Score as an assessment tool for grading the course of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: comparison with the National Cancer Institute-Common Toxicity Scale. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2007.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavaletti G, Jann S, Pace A, Plasmati R, Siciliano G, Briani C, Cocito D, Padua L, Ghiglione E, Manicone M, Giussani G Italian NETox Group. Multi-center assessment of the Total Neuropathy Score for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2006.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornblath DR, Chaudhry V, Carter K, Lee D, Seysedadr M, Miernicki M, Joh T. Total neuropathy score: validation and reliability study. Neurology. 1999;53:1660–1664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ness KK, Kaste SC, Zhu L, Pui CH, Jeha S, Nathan PC, Inaba H, Wasilewski-Masker K, Shah D, Wells RJ, Karlage RE, Robison LL, Cox CL. Skeletal, neuromuscular and fitness impairments among children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1004–1011. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.944519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galea V, Wright MJ, Barr RD. Measurement of balance in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Gait Posture. 2004;19:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Luca CR, McCarthy M, Galvin J, Green JL, Murphy A, Knight S, Williams J. Gross and fine motor skills in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16:180–187. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2013.771221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabarre CL, Rassekh SR, Zwicker JG. Vincristine and fine motor function of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: La vincristine et la motricite fine chez les enfants ayant une leucemie aigue lymphoblastique. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0008417414539926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anghelescu DL, Faughnan LG, Jeha S, Relling MV, Hinds PS, Sandlund JT, Cheng C, Pei D, Hankins G, Pauley JL, Pui CH. Neuropathic pain during treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1147–1153. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanbayashi Y, Hosokawa T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Otsuji E, Yoshikawa T, Takagi T, Taniwaki M. Statistical identification of predictors for peripheral neuropathy associated with administration of bortezomib, taxanes, oxaliplatin or vincristine using ordered logistic regression analysis. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:877–881. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833db89d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada N, Hanafusa T, Sakurada T, Teraoka K, Kujime T, Abe M, Shinohara Y, Kawazoe K, Minakuchi K. Risk Factors for Early-Onset Peripheral Neuropathy Caused by Vincristine in Patients With a First Administration of R-CHOP or R-CHOP-Like Chemotherapy. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:252–260. doi: 10.14740/jocmr1856w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verstappen CC, Koeppen S, Heimans JJ, Huijgens PC, Scheulen ME, Strumberg D, Kiburg B, Postma TJ. Dose-related vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy with unexpected off-therapy worsening. Neurology. 2005;64:1076–1077. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000154642.45474.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haim N, Epelbaum R, Ben-Shahar M, Yarnitsky D, Simri W, Robinson E. Full dose vincristine (without 2-mg dose limit) in the treatment of lymphomas. Cancer. 1994;73:2515–2519. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2515::aid-cncr2820731011>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartman A, van den Bos C, Stijnen T, Pieters R. Decrease in motor performance in children with cancer is independent of the cumulative dose of vincristine. Cancer. 2006;106:1395–1401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van den Berg HW, Desai ZR, Wilson R, Kennedy G, Bridges JM, Shanks RG. The pharmacokinetics of vincristine in man: reduced drug clearance associated with raised serum alkaline phosphatase and dose-limited elimination. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1982;8:215–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00255487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore AS, Norris R, Price G, Nguyen T, Ni M, George R, van Breda K, Duley J, Charles B, Pinkerton R. Vincristine pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenetics in children with cancer: a limited-sampling, population modelling approach. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:875–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crom WR, de Graaf SS, Synold T, Uges DR, Bloemhof H, Rivera G, Christensen ML, Mahmoud H, Evans WE. Pharmacokinetics of vincristine in children and adolescents with acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Pediatr. 1994;125:642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moriyama B, Henning SA, Leung J, Falade-Nwulia O, Jarosinski P, Penzak SR, Walsh TJ. Adverse interactions between antifungal azoles and vincristine: review and analysis of cases. Mycoses. 2012;55:290–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Schie RM, Bruggemann RJ, Hoogerbrugge PM, te Loo DM. Effect of azole antifungal therapy on vincristine toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1853–1856. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang L, Yu L, Chen X, Hu Y, Wang B. Clinical Analysis of Adverse Drug Reactions between Vincristine and Triazoles in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1656–1661. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baxter CG, Marshall A, Roberts M, Felton TW, Denning DW. Peripheral neuropathy in patients on long-term triazole antifungal therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2136–2139. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diouf B, Crews KR, Lew G, Pei D, Cheng C, Bao J, Zheng JJ, Yang W, Fan Y, Wheeler HE, Wing C, Delaney SM, Komatsu M, Paugh SW, McCorkle JR, Lu X, Winick NJ, Carroll WL, Loh ML, Hunger SP, Devidas M, Pui CH, Dolan ME, Relling MV, Evans WE. Association of an inherited genetic variant with vincristine-related peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2015;313:815–823. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Renbarger JL, McCammack KC, Rouse CE, Hall SD. Effect of race on vincristine-associated neurotoxicity in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:769–771. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hertz DL, Roy S, Motsinger-Reif AA, Drobish A, Clark LS, McLeod HL, Carey LA, Dees EC. CYP2C8* 3 increases risk of neuropathy in breast cancer patients treated with paclitaxel. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1472–1478. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider BP, Zhao F, Wang M, Stearns V, Martino S, Jones V, Perez EA, Saphner T, Wolff AC, W SG Jr, Wood WC, Davidson NE, Sparano JA. Neuropathy is not associated with clinical outcomes in patients receiving adjuvant taxane-containing therapy for operable breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:3051–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guilhaumou R, Solas C, Bourgarel-Rey V, Quaranta S, Rome A, Simon N, Lacarelle B, Andre N. Impact of plasma and intracellular exposure and CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 genetic polymorphisms on vincristine-induced neurotoxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1633–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guilhaumou R, Simon N, Quaranta S, Verschuur A, Lacarelle B, Andre N, Solas C. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of vincristine in paediatric patients treated for solid tumour diseases. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1191–1198. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frost BM, Lonnerholm G, Koopmans P, Abrahamsson J, Behrendtz M, Castor A, Forestier E, Uges DR, de Graaf SS. Vincristine in childhood leukaemia: no pharmacokinetic rationale for dose reduction in adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leishear K, Boudreau RM, Studenski SA, Ferrucci L, Rosano C, de Rekeneire N, Houston DK, Kritchevsky SB, Schwartz AV, Vinik AI, Hogervorst E, Yaffe K, Harris TB, Newman AB, Strotmeyer ES Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Relationship between vitamin B12 and sensory and motor peripheral nerve function in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jain P, Gulati S, Toteja GS, Bakhshi S, Seth R, Pandey RM. Serum alpha tocopherol, vitamin B12, and folate levels in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors with and without neuropathy. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:786–788. doi: 10.1177/0883073814535495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chauvenet AR, Shashi V, Selsky C, Morgan E, Kurtzberg J, Bell B Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Vincristine-induced neuropathy as the initial presentation of charcot-marie-tooth disease in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:316–320. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neumann Y, Toren A, Rechavi G, Seifried B, Shoham NG, Mandel M, Kenet G, Sharon N, Sadeh M, Navon R. Vincristine treatment triggering the expression of asymptomatic Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;26:280–283. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199604)26:4<280::AID-MPO12>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olek MJ, Bordeaux B, Leshner RT. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type I diagnosed in a 5-year-old boy after vincristine neurotoxicity, resulting in maternal diagnosis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1999;99:165–167. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.1999.99.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McGuire SA, Gospe SM Jr, Dahl G. Acute vincristine neurotoxicity in the presence of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type I. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1989;17:520–523. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950170534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ichikawa M, Suzuki D, Inamoto J, Ohshima J, Cho Y, Saitoh S, Kaneda M, Iguchi A, Ariga T. Successful alternative treatment containing vindesine for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:239–241. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182352cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bahl A, Chakrabarty B, Gulati S, Raju KN, Raja A, Bakhshi S. Acute onset flaccid quadriparesis in pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma: vincristine induced or Guillain-Barre syndrome? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:1234–1235. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moudgil SS, Riggs JE. Fulminant peripheral neuropathy with severe quadriparesis associated with vincristine therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1136–1138. doi: 10.1345/aph.19396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Egbelakin A, Ferguson MJ, MacGill EA, Lehmann AS, Topletz AR, Quinney SK, Li L, McCammack KC, Hall SD, Renbarger JL. Increased risk of vincristine neurotoxicity associated with low CYP3A5 expression genotype in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:361–367. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lamba J, Assem M, Schuetz J, Watkins PB, Daly A, Wrighton SA, Hall SD, Maurel P, Relling M, Brimer C, Yasuda K, Venkataramanan R, Strom S, Thummel K, Boguski MS, Schuetz E. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet. 2001;27:383–391. doi: 10.1038/86882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ceppi F, Langlois-Pelletier C, Gagne V, Rousseau J, Ciolino C, De Lorenzo S, Kevin KM, Cijov D, Sallan SE, Silverman LB, Neuberg D, Kutok JL, Sinnett D, Laverdiere C, Krajinovic M. Polymorphisms of the vincristine pathway and response to treatment in children with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1105–1116. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hartman A, van Schaik RH, van der Heiden IP, Broekhuis MJ, Meier M, den Boer ML, Pieters R. Polymorphisms in genes involved in vincristine pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics are not related to impaired motor performance in children with leukemia. Leuk Res. 2010;34:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Plasschaert SL, Groninger E, Boezen M, Kema I, de Vries EG, Uges D, Veerman AJ, Kamps WA, Vellenga E, de Graaf SS, de Bont ES. Influence of functional polymorphisms of the MDR1 gene on vincristine pharmacokinetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gutierrez-Camino A, Martin-Guerrero I, Lopez-Lopez E, Echebarria-Barona A, Zabalza I, Ruiz I, Guerra-Merino I, Garcia-Orad A. Lack of association of the CEP72 rs924607 TT genotype with vincristine-related peripheral neuropathy during the early phase of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment in a Spanish population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;26:100–2. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Gavin P, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice J, Schneider B, Smith ML, Smith T, Terstriep S, Wagner-Johnston N, Bak K, Loprinzi CL American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:1941–1967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kautio AL, Haanpaa M, Leminen A, Kalso E, Kautiainen H, Saarto T. Amitriptyline in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic symptoms. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2601–2606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koeppen S, Verstappen CC, Korte R, Scheulen ME, Strumberg D, Postma TJ, Heimans JJ, Huijgens PC, Kiburg B, Renzing-Kohler K, Diener HC. Lack of neuroprotection by an ACTH (4-9) analogue. A randomized trial in patients treated with vincristine for Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muller L, Moorervandelft C, Kiburg B, Vermorken J, Heimans J, Boer H. Org-2766, an acth(4-9)-msh(4-9) analog, modulates vincristine-induced neurotoxicity in the snail lymnaea-stagnalis. Int J Oncol. 1994;5:647–653. doi: 10.3892/ijo.5.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kemp G, Rose P, Lurain J, Berman M, Manetta A, Roullet B, Homesley H, Belpomme D, Glick J. Amifostine pretreatment for protection against cyclophosphamide-induced and cisplatin-induced toxicities: results of a randomized control trial in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:2101–2112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lorusso D, Ferrandina G, Greggi S, Gadducci A, Pignata S, Tateo S, Biamonte R, Manzione L, Di Vagno G, Ferrau’ F, Scambia G Multicenter Italian Trials in Ovarian Cancer invesitgators. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of amifostine as cytoprotectant in first-line chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Planting AS, Catimel G, de Mulder PH, de Graeff A, Hoppener F, Verweij J, Oster W, Vermorken JB. Randomized study of a short course of weekly cisplatin with or without amifostine in advanced head and neck cancer. EORTC Head and Neck Cooperative Group. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:693–700. doi: 10.1023/a:1008353505916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kanat O, Evrensel T, Baran I, Coskun H, Zarifoglu M, Turan OF, Kurt E, Demiray M, Gonullu G, Manavoglu O. Protective effect of amifostine against toxicity of paclitaxel and carboplatin in non-small cell lung cancer: a single center randomized study. Med Oncol. 2003;20:237–245. doi: 10.1385/MO:20:3:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leong SS, Tan EH, Fong KW, Wilder-Smith E, Ong YK, Tai BC, Chew L, Lim SH, Wee J, Lee KM, Foo KF, Ang P, Ang PT. Randomized double-blind trial of combined modality treatment with or without amifostine in unresectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:1767–1774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Durand JP, Deplanque G, Montheil V, Gornet JM, Scotte F, Mir O, Cessot A, Coriat R, Raymond E, Mitry E, Herait P, Yataghene Y, Goldwasser F. Efficacy of venlafaxine for the prevention and relief of oxaliplatin-induced acute neurotoxicity: results of EFFOX, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:200–205. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, Fleishman S, Paskett ED, Ahles T, Bressler LR, Fadul CE, Knox C, Le-Lindqwister N, Gilman PB, Shapiro CL Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rao RD, Michalak JC, Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Soori GS, Nikcevich DA, Warner DO, Novotny P, Kutteh LA, Wong GY North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Efficacy of gabapentin in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial (N00C3) Cancer. 2007;110:2110–2118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiao W, Boroujerdi A, Bennett GJ, Luo ZD. Chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy: analgesic effects of gabapentin and effects on expression of the alpha-2-delta type-1 calcium channel subunit. Neuroscience. 2007;144:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gauchan P, Andoh T, Ikeda K, Fujita M, Sasaki A, Kato A, Kuraishi Y. Mechanical allodynia induced by paclitaxel, oxaliplatin and vincristine: different effectiveness of gabapentin and different expression of voltage-dependent calcium channel alpha(2) delta-1 subunit. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:732–734. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rao RD, Flynn PJ, Sloan JA, Wong GY, Novotny P, Johnson DB, Gross HM, Renno SI, Nashawaty M, Loprinzi CL. Efficacy of lamotrigine in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, N01C3. Cancer. 2008;112:2802–2808. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barton DL, Wos EJ, Qin R, Mattar BI, Green NB, Lanier KS, Bearden JD 3rd, Kugler JW, Hoff KL, Reddy PS, Rowland KM Jr, Riepl M, Christensen B, Loprinzi CL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a topical treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: NCCTG trial N06CA. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:833–841. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marchese VG, Chiarello LA, Lange BJ. Effects of physical therapy intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:127–133. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Visovsky C, Meyer RR, Roller J, Poppas M. Evaluation and management of peripheral neuropathy in diabetic patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:243–247. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Norman M, Elinder G, Finkel Y. Vincristine neuropathy and a Guillain-Barre syndrome: a case with acute lymphatic leukemia and quadriparesis. Eur J Haematol. 1987;39:75–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1987.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]