Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome of excessive immune activation that mimics and occurs with other systemic diseases. A 35-year-old female presented with signs of viral illness at 13 weeks of pregnancy and progressed to acute liver failure (ALF). We discuss the diagnosis of HLH and Kikuchi-Fujimoto (KF) lymphadenitis in the context of pregnancy and ALF. HLH may respond to comorbid disease-specific therapy, and more toxic treatment can be avoided.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare disease associated with a dysregulated inflammatory response and damage to multiple organs.1 There are several triggers for HLH,2 and successful treatment requires prompt initiation of therapy.3

Case Report

A 35-year-old Indian woman, gravida 2 para 1, presented at 13 weeks gestational age for upper respiratory infection symptoms and painful left posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. She had no prior medical history. She was diagnosed with probable streptococcal pharyngitis and treated with amoxicillin clavulanate for 10 days.

The patient returned 6 weeks later with jaundice and fever. Her blood pressure was normal but her temperature fluctuated between 36.7ºC and 41ºC. She had normal mental status, scleral icterus, a non-tender left cervical lymph node, and a normal 20-week gravid abdomen. Liver biochemistries showed aspartate aminotransferase 2,781 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 1,497 U/L, total bilirubin 11.6 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 108 U/L, and international normalized ratio 1.6. Renal function, complete blood count, eosinophil count, and urine analysis were normal. She was admitted for further evaluation. Her liver and obstetric ultrasounds were normal. An extensive infectious, auto-immune, and metabolic work-up was negative, except for ferritin 4,567 ug/L and a nonspecific smooth muscle antibody titer of 1:40 (Table 1).

Table 1. Negative/Normal Tests on Initial Work-Up.

| Serologies |

| Hepatitis A, B, C, E |

| Cytomegalovirus |

| Epstein-Barr |

| Herpes simplex virus |

| Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Bartonella henselae/Quintana |

| Leptospirosis |

| Leishmaniasis |

| Rapid plasma reagent |

| Bacterial blood cultures |

| Malaria smear |

| Quantiferon-TB-gold |

| Antinuclear antibodies |

| Anti-double stranded DNA |

| Liver-kidney microsomal antibodies |

| Immunoglobulin G |

| Ceruloplasmin |

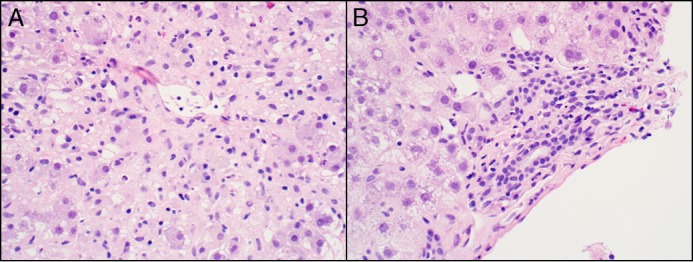

A transjugular liver biopsy was performed on hospital day 8 and showed active hepatitis, confluent pericentral necrosis, and mild, diffuse lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 1). There was no microvesicular steatosis or hemophagocytosis. Fungal and bacterial cultures of the biopsy were negative. On hospital day 11, the patient became hypothermic to 33ºC and hypotensive. She was transferred to the intensive care unit, volume resuscitated, and started on antibiotics. Her temperature rebounded to 38.7ºC on the same day. Her alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase declined to 308 and 858 U/L, respectively, but her bilirubin remained elevated at 16.3 mg/dL. Despite vitamin K administration, her international normalized ratio remained elevated at 1.7. Fibrinogen was low at 80 mg/dL. Her triglyceride level was elevated at 307 mg/dL and her ferritin increased to 10,024 ug/L. Platelets progressively decreased to 67 x 109/L and hemoglobin dropped to 7.8 g/dL.

Figure 1.

Liver biopsy. (A) High-power view of a central zone with confluent necrosis in zone 3 (400x magnification). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a portal tract with mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammation but intact ducts (400x magnification).

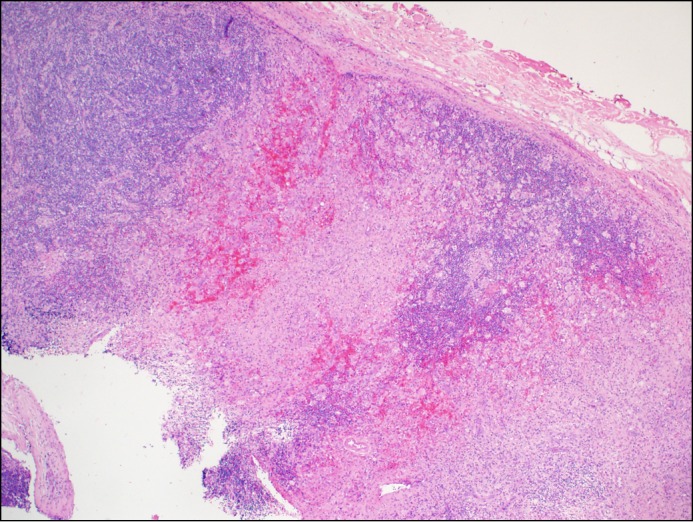

At this point, the patient met 4 out of 8 criteria for HLH (Table 2): fever ≥38.5ºC, cytopenias in at least two lines, hypertriglyceridemia, and ferritin >500 ng/mL. On hospital day 12, an excisional lymph node biopsy showed necrotizing lymphadenitis suspicious for KF lymphadenitis (Figure 2). There were no hemophagocytes in the biopsy. Methylprednisolone was started on day 14 (1 g daily, intravenous) to treat KF lymphadenitis.

Table 2. HLH Clinical Diagnostic Criteria*.

| Five of the eight following criteria: |

| 1. Fever ≥38.5ºC |

| 2. Splenomegaly |

| 3. Cytopenias affecting 2 of the 3 lineages in the peripheral blood |

| Hemoglobin < 9 g/dL |

| Platelets < 100 x 103/mL |

| Neutrophils < 1 x 103/mL |

| 4. Hypertriglyceridemia (fasting, >265 mg/dL) and or hypofibrinogenemia (<150 mg/dL) |

| 5. Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, or liver |

| 6. No or absent natural killer cell activity |

| 7. Ferritin > 500 ng/mL |

| 8. Elevated sCD25 (α-chain of sIL-2 receptor) |

Adapted from Jordan et al (3).

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of lymph node biopsy with characteristic agranulocytic necrosis with apoptotic debris, typical of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (40x magnification).

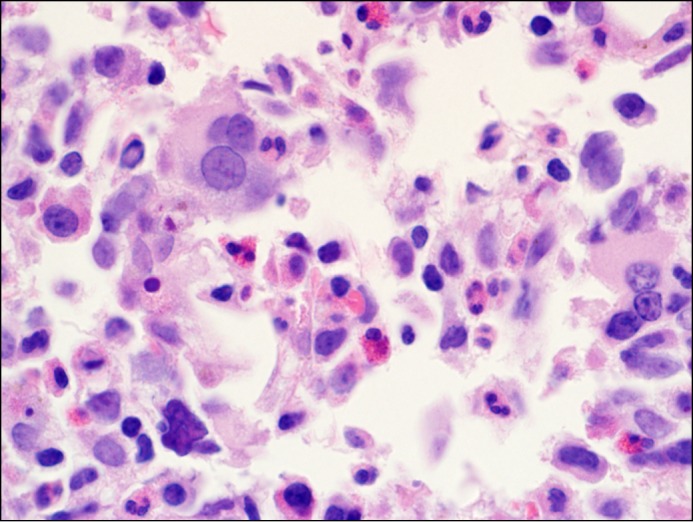

On the same day she developed intermittent somnolence and asterixis. Ammonia level was normal. Imaging of the head was also normal. Electroencephalography showed no seizure activity. Specific tests for HLH (NK cell activity and soluble CD25) were performed, but results would not be available for several days. Given concern for progression to ALF and without an established HLH diagnosis, she was listed for liver transplant. On hospital day 16, a bone marrow biopsy showed evidence of hemophagocytosis (Figure 3). With this finding, the patient met 5 out of 8 of the diagnostic criteria for HLH (Table 2), which is the threshold for confirmation of HLH.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of bone marrow biopsy with hemophagocytosis in the center of the field in which a red cell indents a macrophage nucleus (1,000x magnification).

With no improvement with corticosteroids and the possibility that the pregnancy was driving the inflammatory state, the family elected to terminate the pregnancy. Prior to termination, the patient was started on dexamethasone (20 mg intravenous) and etoposide (75 mg/m2) on hospital day 16 for treatment of HLH. Spontaneous abortion occurred the following day, an hour before scheduled termination. During the next few days, the patient’s bilirubin decreased to 6 mg/dL, and her international normalized ratio normalized. Results from the natural killer cell activity test were significantly low at 4 LU30, and soluble CD25 results were significantly elevated at 11,150 pg/mL.

Over the following 2 weeks, she received 2 additional doses of etoposide. Her fevers resolved, ferritin decreased, and soluble CD25 decreased to 2,085 pg/mL. Despite appropriate treatment with etoposide and dexamethasone, the patient’s pancytopenia and liver biochemistries worsened on day 42, and she died suddenly on day 48. The post mortem examination revealed a proximal pulmonary embolus and a small focus of residual HLH in the peripancreatic fat.

Discussion

HLH is a disease associated with an extreme inflammatory response and multiple organ damage, and is associated with a poor prognosis and a mortality of 40%.1 In this case, it was initially unclear whether the liver injury and altered mental status were related to HLH. The patient’s elevated ferritin initially raised the possibility of HLH. Hyperferritinemia, however, can be seen in other causes of ALF,4 and neurologic symptoms have been described in 33% of patients with HLH.5

The absence of hypertension and proteinuria, the timing of her illness during the second trimester, and the liver biopsy ruled out pregnancy-related causes of ALF. Liver ultrasound did not demonstrate hepatic vein obstruction. Lymphoma and leukemia were ruled out by biopsies. Amoxicillin-induced liver injury was unlikely in the setting of a normal eosinophil count, lack of cholestasis or duct damage on liver biopsy, and the more probable diagnosis of HLH.

In a review of HLH cases, an associated disease was identified 96% of the time, including viral infection (35%) and hematological neoplasm (45%).1 Some cases of HLH will respond to disease-specific therapy, and treatment with etoposide and corticosteroids can be avoided.3

Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis is an idiopathic disease that is predominantly found in young women.6 Most patients with KF lymphadenitis have localized adenopathy of the cervical chain and a third of patients have fever. KF lymphadenitis is usually self-limited, with adenopathy disappearing in several weeks. In this case, we decided to treat with corticosteroids in light of the extranodal manifestations.

HLH diagnostic criteria share some common features with KF disease (Table 2). There are 10 published cases of KF lymphadenitis associated with HLH,7-14 8 cases of KF diagnosed during pregnancy,6 and HLH during pregnancy has been reported in 14 cases.7,15,16 Out of the 14 cases of HLH in pregnancy, one bears some similarity to our patient’s presentation, as she was also diagnosed with KF disease.7 In that case, early delivery was initiated at 30 weeks; the patient died but the infant survived.

Due to our patient’s rapid deterioration, we listed her for liver transplantation (LT) prior to confirming HLH diagnosis. We were aware of the high mortality following LT for HLH but we considered LT until the diagnosis was confirmed.17 The patient’s liver function recovered rapidly following spontaneous abortion and institution of HLH-directed therapy, therefore LT was no longer indicated. Liver transplantation shouldn’t be considered as a treatment of HLH, as the liver failure is only a manifestation of the general HLH inflammatory storm and not the culprit.1 Two cases of LT for HLH are found in the literature; both patients died from HLH recurrence less than 2 months after transplant.17-18

Thorough evaluation confirmed KF lymphadenitis and HLH, both of which we believe were induced by pregnancy-related immune dysregulation. We believe the spontaneous abortion was an important factor leading to the patient’s clinical improvement; it was unlikely due to corticosteroids alone and too soon to be explained by etoposide given 1 day earlier.

Although our patient’s liver function improved, she died from a massive pulmonary embolism, probably related to hypercoagulability associated with HLH, peripartum state, and immobility. The worsening of her liver tests and pancytopenia prior to her death was probably due to persistent HLH as noted on autopsy, a disappointing but not surprising result given the poor prognosis associated with HLH.

Disclosures

Author contributions: JM Giard, KA Decker, JC Lai, and AC Logan drafted the manuscript. RM Gill analyzed the pathology slides and drafted the manuscript. OK Fix reviewed the manuscript. JM Giard is the article guarantor.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

References

- 1.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. The Lancet. 2014; 383(9927):1503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shabbir M, Lucas J, Lazarchick J, Shirai K. Secondary hemophagocytic syndrome in adults: A case series of 18 patients in a single institution and a review of literature. Hematol Oncol. 2011; 29(2):100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011; 118(15):4041–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotoh K, Ueda A, Tanaka M, et al. A high prevalence of extreme hyperferritinemia in acute hepatitis patients. Hepat Med. 2009; 1:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: Recent insights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010; 16(1 Suppl):S82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astudillo L. [ Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease]. Rev Med Interne. 2010; 31(11):757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chmait RH, Meimin DL, Koo CH, Huffaker J. Hemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95(6 Pt 2):1022–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yufu Y, Matsumoto M, Miyamura T, et al. Parvovirus B19-associated haemophagocytic syndrome with lymphadenopathy resembling histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi's disease). Br J Haematol. 1997; 96(4):868–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leyral C, Camou F, Perlemoine C, et al. [Pathogenic links between Kikuchi's disease and lupus: A report of three new cases]. Rev Med Interne. 2005; 26(8):651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JS, Chang KC, Cheng CN, et al. Childhood hemophagocytic syndrome associated with Kikuchi's disease. Haematologica. 2000; 85(9):998–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampitak T. Fatal Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease associated with SLE and hemophagocytic syndrome: A case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2008; 27(8):1073–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahadeva U, Allport T, Bain B, Chan WK. Haemophagocytic syndrome and histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis (Kikuchi's disease). J Clin Pathol. 2000; 53(8):636–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meni C, Chabrol A, Wassef M, et al. [An atypical presentation of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease]. Rev Med Interne. 2013; 34(6):373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wano Y, Ebata K, Masaki Y, et al. [Histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto's disease) accompanied by hemophagocytosis and salivary gland swelling in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2000; 41(1):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn T, Cho M, Medeiros B, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy: A case report and review of treatment options. Hematology. 2012; 17(6):325–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayama M, Yoshihara M, Kokabu T, Oguchi H. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with a parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 124(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):438–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright G, Wilmore S, Makanyanga J, et al. Liver transplant for adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Case report and literature review. Exp Clin Transplant. 2012; 10(5):508–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parizhskaya M, Reyes J, Jaffe R. Hemophagocytic syndrome presenting as acute hepatic failure in two infants: Clinical overlap with neonatal hemochromatosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999; 2(4):360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]