Abstract

The genus Paris in the broad concept is an economically important group in the monocotyledonous family Melanthiaceae (tribe Parideae). The phylogeny of Paris was controversial in previous morphology-based classification and molecular phylogeny. Here, the complete cp genomes of eleven Paris taxa were sequenced, to better understand the evolutionary relationships among these plants and the mutation patterns in their chloroplast (cp) genomes. Comparative analyses indicated that the overall cp genome structure among the Paris taxa is quite similar. The triplication of trnI-CAU was found only in the cp genomes of P. quadrifolia and P. verticillata. Phylogenetic analyses based on the complete cp genomes did not resolve Paris as a monophyletic group, instead providing evidence supporting division of the twelve taxa into two segregate genera: Paris sensu strict and Daiswa. The sister relationship between Daiswa and Trillium was well supported. We recovered two fully supported lineages with divergent distribution in Daiswa; however, none of the previously recognized sections in Daiswa was resolved as monophyletic using plastome data, suggesting that the infrageneric relationships and biogeography of Daiswa species require further investigation. Ten highly divergent DNA regions, suitable for species identification, were detected among the 12 cp genomes. This study is the first successful attempt to provide well-supported evolutionary relationships in Paris based on phylogenomic analyses. The findings highlight the potential of the whole cp genomes for improving resolution in phylogeny as well as species identification in phylogenetically and taxonomically difficult plant genera.

Keywords: comparative genomics, phylogeny, chloroplast genome, Paris, Daiswa, Melanthiaceae

Introduction

The genus Paris in the wide sense (hereafter indicated by Paris), belongs to the tribe Parideae in the monocotyledonous family Melanthiaceae (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016), which comprises approximately 24 perennial herbaceous species, distributed throughout Europe and East Asia, with the majority of species (19/24) occurring in China (Li, 1998; Ji et al., 2006). Paris is well known in China for its medicinal qualities. The species with a thick rhizome (“medicinal Paris”) has been used as medicinal herb for more than 2000 years in China (Li, 1986), owing to its analgesic, hemostatic, anti-tumor, and anti-inflammatory activities (Long et al., 2003; He et al., 2006; Li et al., 2015). To date, more than 40 commercial drugs and health products have been developed in China using the rhizomes of “medicinal Paris” as raw materials (Li et al., 2015).

The classification of Paris is very complicated because of the plasticity of its morphological characteristics, and it has been subject to numerous critical revisions since the establishment. Hara (1969); Mitchell (1987, 1988), and Li (1998) recognized it as a single genus, whereas Takhtajan (1983) divided it into three genera: Paris sensu strict (s.s), Daiswa, and Kinugasa. The molecular phylogeny of Paris based on either single or multiple-locus DNA sequence data (e.g., rbcL, matK, trnL/trnF, psbA/trnH and ITS) has remained controversial in recent investigations. The monophyly of Paris was justified by the studies of Osaloo and Kawano (1999) and Ji et al. (2006); however, analyses by Farmer and Schilling (2002) supported the taxonomical treatment of Takhtajan (1983). Despite recent insights into the evolutionary relationships within this plant group, a fully resolved and well-supported phylogeny remains elusive. It is, therefore, necessary to seek further evidence to reconstruct the phylogeny and to test the various classifications.

In addition, most Paris species have abundant intraspecific variations in morphology and chemical composition (Li, 1998; Ji et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2015). Inaccurate identification of these species could confound their effective exploration, conservation, and domestication. Moreover, at the species level, nearly all reported chloroplast (cp) DNA sequences (rbcL, matK, trnL/trnF, and psbA/trnH) exhibit inadequate genetic variation (Osaloo and Kawano, 1999; Ji et al., 2006), to allow reliable discrimination of these species.

As complete cp genome sequences can offer valuable information for the reconstruction of complex evolutionary relationships in plants, they have been widely used for plant phylogenetic analyses and species identification in recent years (Jansen et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2007, 2010; Parks et al., 2009; Nock et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013; Ruhsam et al., 2015). In the current study, we sequenced the complete cp genomes of eleven Paris taxa and compared these with the previously reported cp genome of P. verticillata (Do et al., 2014). The sampling covered almost half of species recognized by the updated classification (Li, 1998; Ji et al., 2006), and we carried out a comprehensive analysis of cp genomes in this phylogenetically and taxonomically difficult plant group. The primary objectives of the current study were: (1) to investigate the global cp genome structure of Paris species; (2) to test the previous classifications of Paris using complete cp genome sequences; and (3) to screen for sequence divergence hotspot regions among the twelve cp genomes as potential DNA barcodes for species identification.

Materials and Methods

Taxon Sampling, Sequencing, and Genome Assembly

Eleven taxa of Paris cultivated in the greenhouse in Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences were sampled. Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of clean, fresh leaves using the CTAB method (Doyle, 1987). Complete chloroplast genomes were amplified using Takara PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (Takara, Dalian, Liaoning, China) and nine universal pairs of primers and protocols developed by Yang et al. (2014). Purified PCR products were mixed and then digested into 200–500 base pairs (bp) fragments, and paired-end libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s manual (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The libraries were sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencing platform at BGI (Shenzhen, Guangdong, China).

Raw reads were filtered using NGSQC Toolkit (Patel and Jain, 2012), with the cut-off value for percentage of read length = 80, cut-off value for PHRED quality score = 30. High-quality reads were assembled into contigs using CLC Genomics Workbench v8.0 (CLC BIO, Aarhus, Denmark) with a minimum length of 1,000 bp. Next, all the contigs were aligned to the reference cp genome of Paris verticillata (KJ433485; Do et al., 2014), and aligned contigs were ordered according to the reference cp genome. Based on the reference cp genome, Contigs were reassembled and extended to obtain a complete cp genome sequence in Geneious 7.0 (Kearse et al., 2012), using the algorithm MUMmer. The validated complete cp genome sequences were deposited in GenBank (Supplementary Table S1).

Genome Annotation and Comparison

Complete cp genomes were annotated using the Dual OrganellarGenome Annotator (DOGMA) database (Wyman et al., 2004). Start and stop codons and intron/exon boundaries were checked manually. Identified tRNA genes were verified using tRNAscan-SE 1.21 (Schattner et al., 2005) with the default parameters. The cp genome maps were drawn by the software OrganellarGenomeDRAW (Lohse et al., 2007). Comparison of the sequence divergence among the twelve cp genomes was performed using the mVISTA tool (Frazer et al., 2004) with the default parameters, and P. verticillata was set as a reference. To identify the mutations among 12 cp genomes, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified using the tools embedded in Geneious 7.0 (Kearse et al., 2012), with the option setting as “Only Find SNPs.” Then, the variant frequency of SNPs in the protein coding and non-coding regions was calculated manually to detect the divergence hotspots across Paris cp genomes.

Phylogenetic Analyses

The 12 completed Paris cp genomes were included in the analysis, of which 11 were newly generated in the current study (Supplementary Table S1). To reconstruct the phylogeny of Paris, eight species outside of Paris were included in the ingroup, representing all five tribes (Heloniadeae, Chionographideae, Xerophylleae, Melanthieae, and Parideae) recognized in the family Melanthiaceae (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016). The complete cp genomes from Smilax china, Fritillaria cirrhosa, and Luzuriaga radicans were used to root the tree. The published complete cp genomes were downloaded from the NCBI GenBank database (Supplementary Table S1).

Phylogenetic analyses were carried out by maximum likelihood analysis (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). The ML analyses were performed using RAxML-HPC BlackBox version 8.1.24 (Stamatakis et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2010). The best-fitting substitution model was selected using ModelTest (Posada, 2008) and branch support was computed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The BI analyses were performed using MrBayes 3.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). Four Markov chains, starting with a random tree, were run simultaneously for one million generations, sampling trees every 2,000 generations. Trees from the first 250,000 generations were regarded as “burn in” and discarded, with posterior probability values determined from the remaining trees.

Results

Chloroplast Genome Features

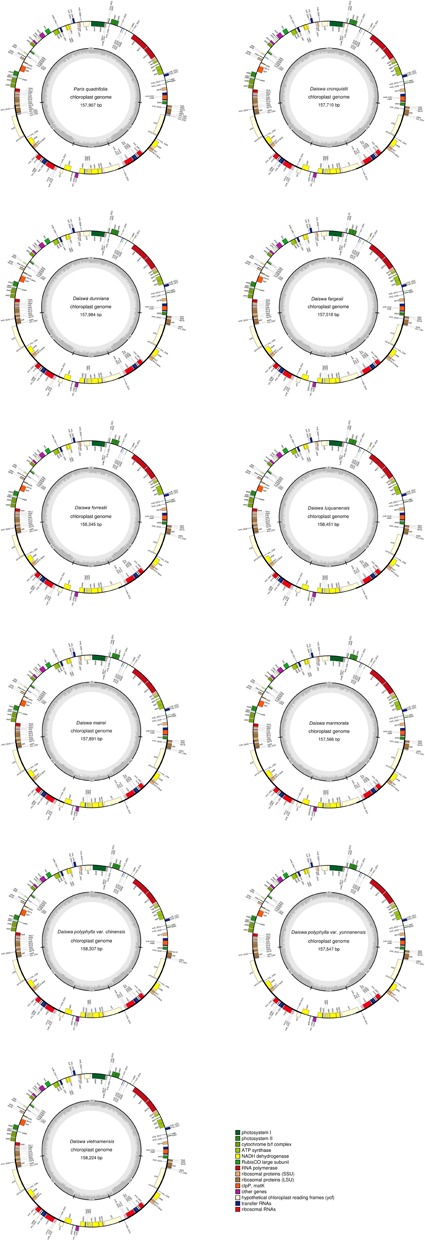

The twelve Paris complete cp genomes ranged from 157,379 to 158,451base paris (bp). All the cp genomes possessed the typical quadripartite structure of angiosperms, consisting of a pair of inverted repeated regions (IRs: 27,329–28,373 bp) separated by a large single-copy region (LSC: 82,726–85,187 bp) and a small single-copy region (SSC: 17,907–18,671 bp) (Figure 1; Table 1). All the 12 cp genomes possessed 115 unique genes arranged in the same order, including 81 protein-coding, 30 tRNA, and 4 rRNA genes. Of these, twelve protein-coding genes and six tRNAs contained at least one intron (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Map of the 11 Paris chloroplast genomes newly generated in the current study. Genes shown outside the circle are transcribed clockwise and those inside are transcribed counterclockwise. The dark gray area in the inner circle indicates the CG content of the chloroplast genome.

Table 1.

The comparison of the 12 Paris chloroplast genomes.

| Taxa | Genome size (bp) | GC content (%) | LSC (bp) | SSC (bp) | IR (bp) | IR/SSC junction | IR/LSC junction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. marmorata | 157566 | 37.3 | 84221 | 18301 | 27522 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. forrestii | 158345 | 37.3 | 84396 | 18671 | 27639 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. polyphylla var. yunnanensis | 157547 | 37.3 | 84224 | 18319 | 27502 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. luquanensis | 158451 | 37.3 | 84408 | 18403 | 27820 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. marei | 157891 | 37.3 | 84420 | 18361 | 27555 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. vietnamensis | 158224 | 37.2 | 84794 | 18360 | 27535 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. fargesii | 157518 | 37.3 | 84549 | 18311 | 27329 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. cronquistii | 157710 | 37.3 | 84502 | 18316 | 27446 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| D. polyphylla var. chinensis | 158307 | 37.2 | 85187 | 18175 | 27473 | ycf1 | rps19 |

| D. dunniana | 157984 | 37.2 | 84482 | 18364 | 27569 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| P. verticillata | 157379 | 37.6 | 82726 | 17907 | 28373 | ycf1 | rps3 |

| P. quadrifolia | 157907 | 37.7 | 83772 | 18287 | 27924 | ycf1 | rps3 |

Table 2.

List of genes encoded by 12 Paris chloroplast genomes.

| Category of genes | Group of gene | Name of gene |

|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | Ribosomal RNA genes | rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, rrn23 |

| Transfer RNA genes | trnA_UGC∗, trnC_GCA, trnD_GUC, trnE_UUC, trnF_GAA, trnfM_CAU, trnG_GCC, trnG_UCC∗, trnH_GUG, trnI_CAU, trnI_GAU∗, trnK_UUU∗, trnL_CAA, trnL_UAA∗, trnL_UAG, trnM_CAU, trnN_GUU, trnP_UGG, trnQ_UUG, trnR_ACG, trnR_UCU, trnS_GCU, trnS_GGA, trnS_UGA, trnT_GGU, trnT_UGU, trnV_GAC, trnV_UAC∗, trnW_CCA, trnY_GUA | |

| Ribosomal protein (small subunit) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12, rps12∗, rps14, rps15, rps16∗, rps18, rps19 | |

| Ribosomal protein (large subunit) | rpl2∗, rpl14, rpl16∗, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | |

| RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1∗, rpoC2 | |

| Translational initiation factor | infA | |

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, ycf3∗∗, ycf4 |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of cytochrome | petA, petB∗, petD∗, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF∗, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit of Rubisco | rbcL | |

| Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA∗, ndhB∗, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA# | |

| Subunit of acetyl-CoA | accD | |

| Synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| ATP-dependent protease | clpP∗∗ | |

| Component of TIC complex | ycf1 | |

| Genes of unknown function | Conserved open reading frames | ycf2, ycf15# |

∗With one intron; ∗∗With two introns; #Pseudogene.

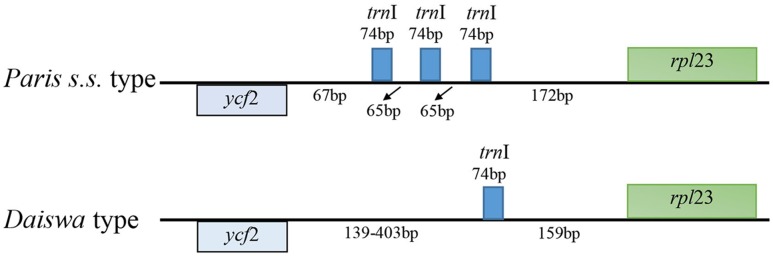

The Paris cp genomes exhibited significant IR expansion. Expansion of IR regions into rps3 at the IR/LSC boundaries was detected in all taxa, except for Daiswa polyphylla var. chinensis, where the IR regions expanded into rps19 (Table 1). Expansion of the IR region into the ycf1 pseudo-gene at IR/SSC junction regions occurred in all Paris taxa, leading to an overlap between the ycf1 pseudo-gene and ndhF (Table 1). The length of the intergenic spacer between rpl23 and ycf2 was highly variable among the twelve cp genomes. Two patterns of variation (designated as Paris s.s. and Daiswa types) based on the number of copies of trnI-CAU were observed (Figure 2). The Paris s.s type possessed three copies of trnI-CAU, and was present in P. verticillata and P. quadrifolia. The Daiswa type, including only a single copy of trnI-CAU, was identified in the remaining taxa.

FIGURE 2.

The two types of trnI-CAU gene duplication detected in Paris taxa.

Phylogenomic Analyses

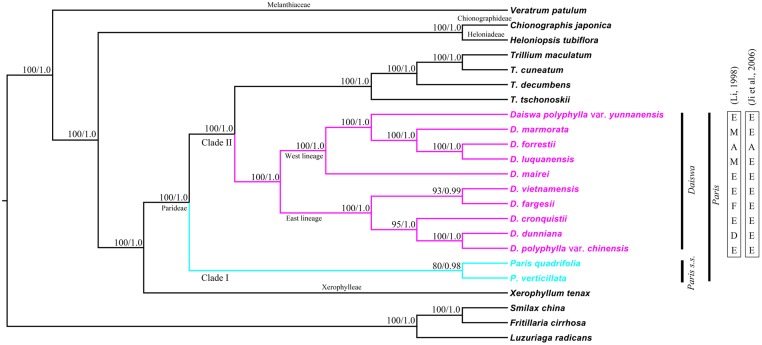

Phylogenetic relationships within the Melanthiaceae family were reconstructed by ML and BI analyses. The resulting ML and BI tree topologies were highly similar to one another. Figure 3 illustrates the phylogeny generated by ML analysis, including two types of support values: ML bootstrap values (MLBS) and BI posterior probabilities (PP). Both analyses fully supported the monophyly of the tribe Parideae (Trillium + Paris) (MLBS = 100% and PP = 1.00). The basal divergence within the Parideae formed two major clades (I and II). Clade I (MLBS = 80% and PP = 0.98) comprised P. quadrifolia and P. verticillata, corresponding to the Paris s.s outlined by Takhtajan (1983). Clade II was resolved as two subclades (MLBS = 100%, PP = 1.00): Trillium, and another, consisting of species placed in the genus Daiswa by Takhtajan (1983). The phylogenetic relationships recovered by analysis of whole cp genome sequences did not support Paris as a monophyletic group.

FIGURE 3.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny of Melanthiaceae based on complete chloroplast genomes inferred from 20 taxa representing all five tribes of the family. Numbers indicate bootstrap values >80% from the ML analyses and posterior probabilities >0.90 from the Bayesian inference (BI) analyses. Section delimitations in the Daiswa species reported by Li (1998) and Ji et al. (2006) are shown on the right. A, sect. Axiparis; D, sect. Dunnianae; E, sect. Euthyra; F, sect. Fargesianae; M, sect. Marmoratae.

The results of both ML and BI analyses provided significant evidence to support a sister relationship between Trillium and Daiswa (MLBS = 100% and PP = 1.00). We recovered two lineages (MLBS = 100% and PP = 1.0) in the Daiswa clade; one comprised taxa (D. polyphylla var. chinensis, D. dunniana, D. cronquistii, D. fargesii, and D. vietnamensis) distributed from eastern to central China and Vietnam (the east lineage); whereas the other comprised the species, D. mairei, D. luquanensis, D. forrestii, D. marmorata, and D. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, which are distributed from southwest China to the Himalayas (the west lineage). However, none of the sections in the Daiswa proposed by either Li (1998) or Ji et al. (2006) was resolved as monophyletic (Figure 3).

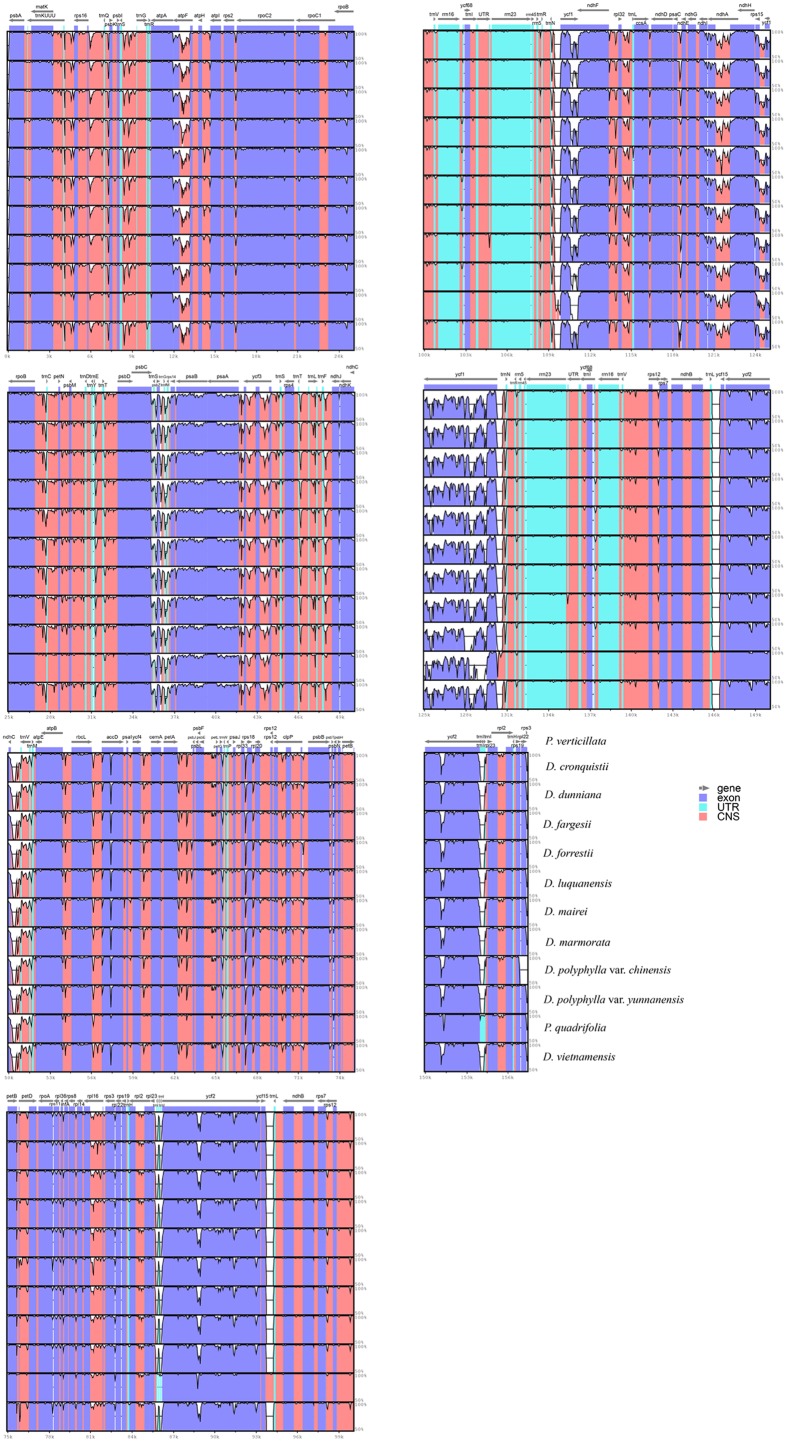

Sequence Divergence Hotspot Regions

Regions containing sequence divergence hotspots were identified by cp genome-wide comparative analyses (Figure 4). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most important marker for species identification (Kress et al., 2005). To identify DNA regions that could be suitable for discriminating Paris species, SNPs across the twelve complete cp genomes were comprehensively examined. We detected 2,748 SNPs (1.756%) among the cp genomes, in which protein-coding genes and non-coding regions (introns and spacers) exhibited divergence proportions of 1.655 and 2.033%, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Among these divergence hotspot regions (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4), we screened 10 non-coding regions with potential to be useful loci for the molecular identification of Paris species, with lengths ranging from 200 to 1,500 bp and percentages of SNPs exceeding 3%. Primers for these plastid DNA markers are presented in Table 3.

FIGURE 4.

Sequence identity plots for the 12 Paris taxa.

Table 3.

Potential DNA barcodes to identify Paris s.s. and Daiswa species.

| Loci | Location | Primers | GC % | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ndhC/trnV-UAC | LSC | F:ACAAAACTTTCTCGCTCGGT R:TTCTATGGACCAAGCAACCG |

45.0 50.0 |

58.1 57.9 |

| trnN-GUU/ycf1 | IRB | F:CCGGAACTTCTTCGTAGTGG R:CCCCGAAGTGGCTCTATTTC |

55.0 55.0 |

58.0 58.0 |

| rps15/ycf1 | SSC | F:CATCTGGTATACGCAAAAGCG R:ACCTATGCGTACATCTTTCGG |

47.6 47.6 |

57.8 57.9 |

| rpl33/rps18 | LSC | F:AACAAAACGCGTGTTCGATC R:ATTTCGGCCGGATCTGAAAT |

45.0 45.0 |

58.0 57.7 |

| ndhA intron | SSC | F:ACCCATGTAATTCTGTCGGC R:GGGGAAGTACTGCTTGATCG |

50.0 55.0 |

58.0 58.1 |

| atpF intron | LSC | F:TTTGGCTCTCACGCTCAATT R:TCGCTTCGGCATTGGATAAA |

45.0 45.0 |

58.1 58.0 |

| psbZ/trnG-GCC | LSC | F:CCTCGATTCAAAAATGCCGT R:GCGAAAATATGATCCAGACGC |

45.0 47.6 |

57.1 57.8 |

| psaA/ycf3 | LSC | F:ACAAAGAGACCTGCCAACAG R:TGCAACCGAGTCCTAGTGTA |

50.0 50.0 |

58.0 58.1 |

| trnV-UAC intron | LSC | F:ACCTTGACTTAGGTCTGCCT R:CAAATCGATGGCGGGTTCTA |

50.0 50.0 |

58.0 58.1 |

| ccsA/ndhD | SSC | F:GGTTCTCAAAAACTCTAGAGGC R:TTGCATTCTACAGCGAACGA |

45.5 45.0 |

56.7 57.9 |

Discussion

Comparative Genomics

Our results revealed that the overall gene content and arrangement within the 12 Paris taxa are largely similar. The IR/LSC boundaries in Paris cp genomes (other than those of D. polyphylla var. chinensis) expand into rps3. This differs from the typical monocot genome structure, in which IR regions expand into rps19 (Kim and Lee, 2004; Yang et al., 2013). Among other taxa in the family Melanthiaceae, IR expansion into rps3 has been observed in Chionographis japonica (Chionographideae; Bodin et al., 2013) and Xerophyllum tenax (Xerophylleae; Do et al., unpublished data). Veratrum patulum (Melanthieae; Do et al., 2013); Heloniopsis tubiflora (Heloniadeae; Do et al., unpublished data); Trillium tschonoskii, T. decumbens, T. cuneatum, and T. maculatum (Parideae; Kim et al., 2016; Schilling et al., unpublished data; and Schilling et al., unpublished data; and Kim et al., 2016; respectively),exhibit the typical monocot genome structure at their IR/LSC junctions. This suggests that the expansion of the IR/LSC junctions into rps3 may have occurred independently during the evolutionary history of the family Melanthiaceae, and may not provide relevant phylogenetic information.

Gene duplications in the cp genomes of higher plants have mainly been found in tRNA genes (Hipkins et al., 1995). Three copies of trnI-CAU, located between rpl23 and ycf 2, were found in the cp genome of P. verticillata and P. quadrifolia in the current study; however, this feature was not identified in the remaining Paris taxa, or in previously examined monocot cp genomes (Do et al., 2014). The triplication of the trnI-CAU gene may be unique to Paris taxa, and could thus provide useful information contributing to the exploration of evolutionary relationships.

Phylogenetic and Taxonomic Resolution

The utilization of too few DNA sequence may result in the incongruence between DNA regions, and can increase the phylogenetic errors (Rokas and Carroll, 2005; Philippe et al., 2011). Therefore, phylogenetic analysis of plant species using a small number of loci might be frequently insufficient to resolve evolutionary relationships, particularly at low taxonomic levels (Parks et al., 2009). The molecular differences in complete cp genome between plant species can offer promising evolutionary information (Jansen et al., 2007; Parks et al., 2009). As a result, the cp genomes sequencing could greatly improve the phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels (Parks et al., 2009; Ruhsam et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2016). Nevertheless, using the complete cp genome to reconstruct evolutionary relationship in those phylogenetically and taxonomically difficult genera has been rarely investigated (Ruhsam et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2016).

The key interest in the current study is to resolve the previously phylogenetic controversies in Paris (Osaloo and Kawano, 1999; Farmer and Schilling, 2002; Ji et al., 2006) by using the complete cp genome sequences. Our phylogenomic analyses did not resolve Paris as a monophyletic group, and strongly supported its division into two monophyletic genera: Paris s.s. and Daiswa (Figure 3). This treatment is justified by both morphological and geographical evidence (Table 4). Species belonging to Paris s.s. have a long, slender rhizome, a round ovary, and seeds without sarcotesta or aril. In contrast, Daiswa species have a thick rhizome, an angular ovary, and seeds covered by juicy sarcotesta or aril (Li, 1998; Ji et al., 2006). In addition, Paris species are concentrated in temperate areas of Eurasia, whereas those belonging to Daiswa are distributed in subtropical and tropical areas of East Asia. It is notable that the triplication of trnI-CAU was observed only in Paris s.s., and not in either Daiswa or other monocots (Do et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; the current study), which may provide further comparative genomic evidence to support this generic circumscription.

Table 4.

Critical characters for Daiswa, Paris s.s. and Trillium.

| Genus | Distribution | Rhizome | Leaves | Flower | Ovary | Seed | No. of trnI-CAU copy in cp genome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daiswa | Subtropical and tropical areas of East Asia | Thick | A whorl of 4–15 net-veined leaves at stem apex | Solitary | Angular | With sarcotesta or aril | one |

| Paris s.s. | Temperate areas of Eurasia | Long and slender | A whorl of 4–15 net-veined leaves at stem apex | Solitary | Rounded | Without sarcotesta or aril | Triplication |

| Trillium | North America and East Asia | Thick | A whorl of 3 net-veined leaves at stem apex | Solitary | Angular | Without sarcotesta or aril | duplication |

Our phylogenomic analyses also well resolved the inter-tribe relationships in the family Melanthiaceae and the inter-generic relationships within the tribe Parideae, with higher support than previous phylogenetic studies that used single or multiple locus DNA sequences data (Osaloo and Kawano, 1999; Farmer and Schilling, 2002; Ji et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2013). This result was consistent with previous findings (Attigala et al., 2016) in which a much higher of support to inter-generic relationships was observed in the cp genomic phylogeny within Arundinarieae tribe (Bambusoideae: Poaceae). The sister relationship between Paris s.s. and Daiswa + Trillium clade can be justified by the morphological synapomorphies of single whorl of net-veined leaves at stem apex and solitary flower (Table 4). In addition, plants of Daiswa and Trillium share a thick rhizome and an angular ovary (Ji et al., 2006), which are probably the synapomorphies grouping these two genera. Nevertheless, a question that remains unresolved by our study is the phylogenetic position of Paris japonica (or Kinugasa japonica). This species was placed into the monotypic genus Kinugasa by Takhtajan (1983). As we did not obtain a sample of this plant, the generic circumscription of Kinugasa and its relationships to the other Parideae genera will require further investigation.

Compared to previous molecular phylogeneitc analyses (Osaloo and Kawano, 1999; Ji et al., 2006; Farmer and Schilling, 2002), our results clearly indicated that all nodes within the Daiswa clade showing a MLBS > 90% and PP > 0.95 (Figure 3). Similar results have also been observed from the whole chloroplast genome analysis of Pinus species (Parks et al., 2009), Araucaria species (Ruhsam et al., 2015), and Acasia species (Williams et al., 2016). Nevertheless, relatively lower node support within Paris s.s. was observed (MLBS = 80%, PP = 0.98, Figure 3). Given that only two species were included in the analyses, this may result in a phylogeny that is more sensitive to homoplasy, and can thus decrease the phylogenetic resolution (Wiens, 2003). Therefore, a much larger taxon sample may provide a better resolution of the infra-generic relationships and species identification in the Paris s.s., as previous studies indicated (Williams et al., 2016).

It is notable that none of the sections within Daiswa which were proposed by either Li (1998) or Ji et al. (2006) was resolved as monophyletic through our analyses of the complete cp genomes. This implies that the previous delimitation of the sections must be reassessed. We recovered two fully supported cladest within the Daiswa. Species within the two lineages have distinctive distribution patterns, with the east lineage being distributed from eastern and central China to Vietnam and the west lineage from southwestern China to the Himalayas. This implies that the extant Daiswa species that occurred between these two geographical regions could have experienced long-term vicariance. However, the sampling within Daiswa in this study may be too low to satisfactorily address this issue, and maternally inherited plastomes can only provide partial insight into evolutionary history (Triplett et al., 2014). The evolutionary relationships and biogeography of Daiswa species require further investigation, including increased sampling of species and infra-specific populations, and application of additional nuclear DNA markers.

Potential DNA Barcodes

Because of the plasticity of the morphological characteristics among Paris species, its taxonomy remains problematic. The plastid loci, rbcL, matK, and psbA/trnH, are recommended as universal DNA barcodes in plants (Hollingsworth et al., 2011); however, we found that the percentage of variation in rbcL and matK were relatively low (1.046 and 0.773%, respectively) among Paris species (Supplementary Table S3). Due to the expansion of the IR into the LSC region, three protein-coding genes (rps3, rps19, and rpl22) were inserted into the psbA/trnH-GUG spacer of Paris species (Figure 1). This cp genome rearrangement could account for the significantly increased length of the psbA/trnH region among these taxa (∼1,200 bp), in which the divergence proportion is unexpectedly low (Ji et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2011). As a result, these three universal plastid DNA barcodes have extremely low power to identify either Paris s.s. or Daiswa species. Thus, the novel DNA barcodes are urgently needed.

The mutation events in the genome were not random but clustered as “hotspots,” which created the highly variable regions throughout the complete cp genomes (Shaw et al., 2007). These sequence divergence hotspot regions could provide adequate genetic information for species identification, and can be used to develop novel DNA barcodes (Parks et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013). We propose ten plastid DNA regions harboring a high proportion of SNPs (Table 3), which are potentially useful for species identification in Paris s.s and Daiswa. The ndhA intron and atpF intron have been widely used for phylogenetic studies (Shaw et al., 2007). The rest eight loci harboring highly genetic variations are newly identified in the current study. Our further research will investigate whether these DNA sequences could serve as reliable and effective DNA barcodes for species from Paris s.s. and Daswa, the two medicinally important genera. We also encourage researchers working on other plant groups to use these loci developed in this study for phylogenetic reconstruction and species identification.

Conclusion

This study is the first attempt to reconstruct phylogeny in Paris with the taxon sample covering 50% known species which represents a wide phylogenetic diversity in this medicinally important plant group. The overall cp genome structure across these plants is highly conserved. The phylogenomic analyses provided the most strongly supported estimate of evolutionary relationships among Paris taxa, which supports the division of these taxa into two segregate genera: Paris s.s and Daiswa. Our study resolved the debates in phylogeny and classification of Paris. Ten rapidly evolving regions were identified across the cp genomes that could serve as potential DNA barcodes for species identification in Paris s.s and Daiswa. The findings justify that the whole cp genome sequencing can offer plenty genetic information for resolving evolution and species identification in those phylogenetically and taxonomically difficult plant genera.

Author Contributions

YJ designed the research; YH, XL, CY, ZY, and JY collected and analyzed the data; YJ, YH, and JY prepared the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Hongtao Li from the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences for his help in data analyses.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was financially supported by the Major Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31590820, 31590823 to Hang Sun), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31070297 to YJ). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01797/full#supplementary-material

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2016). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181 1–20. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attigala L., Wysocki W. P., Duvall M. R., Clark L. G. (2016). Phylogetic estimation and morphorlogical evolution of Arundinarieae (Bambusoideae: Poaceae) based on plastome phylogenomic analysis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 101 111–121. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin S. S., Kim J. S., Kim J. H. (2013). Complete chloroplast genome of Chionographis japonica (Willd.) Maxim. (Melanthiaceae): comparative genomics and evaluation of universal primers for Liliales. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31 1407–1421. 10.1007/s11105-013-0616-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do H. D. K., Kim J. S., Kim J. H. (2013). Comparative genomics of four Liliales families inferred from the complete chloroplast genome sequence of Veratrum patulum O. Loes. (Melanthiaceae). Gene 530 229–235. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do H. D. K., Kim J. S., Kim J. H. (2014). A trnI_CAU triplication event in the complete chloroplast genome of Paris verticillata M. Bieb. (Melanthiaceae, Liliales). Genome Biol. Evol. 6 1699–1706. 10.1093/gbe/evu138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer S. B., Schilling E. E. (2002). Phylogenetic analyses of Trilliaceae based on morphological and molecular data. Syst. Bot. 27 674–692. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer K. A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E. M., Dubchak I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(Suppl. 2), W273–W279. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H. (1969). Variations in Paris polyphylla Smith with reference to other Asiatic species. J. Fac. Sci. Univ. Tokyo Sect. 3 141–180. [Google Scholar]

- He J., Zhang S., Wang H., Chen C. X., Chen S. F. (2006). Advances in studies on and uses of Paris polyphylla var.yunnanensis (Trilliaceae). Acta Bot. Yunnan. 28 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hipkins V. D., Marshall K. A., Neale D. B., Rottmann W. H., Strauss S. H. (1995). A mutation hotspot in the chloroplast genome of a conifer (Douglas-fir: Pseudotsuga) is caused by variability in the number of direct repeats derived from a partially duplicated tRNA gene. Curr. Genet. 27 572–579. 10.1007/BF00314450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth P. M., Graham S. W., Little D. P. (2011). Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS ONE 6:e19254 10.1371/journal.pone.0019254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Cai Z., Raubeson L. A., Daniell H., Leebens-Mack J., Müller K. F., et al. (2007). Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 19369–19374. 10.1073/pnas.0709121104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Fritsch P. W., Li H., Xiao T., Zhou Z. (2006). Phylogeny and classification of Paris (Melanthiaceae) inferred from DNA sequence data. Ann. Bot. 98 245–256. 10.1093/aob/mcl095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., et al. (2012). Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. S., Hong J. K., Chase M. W., Fay M. F., Kim J. H. (2013). Familial relationships of the monocot order Liliales based on a molecular phylogenetic analysis using four plastid loci: matK, rbcL, atpB and atpF-H. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 172 5–21. 10.1111/boj.12039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. J., Lee H. L. (2004). Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 11 247–261. 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. C., Kim J. S., Kim J. H. (2016). Insight into infrageneric circumscription through complete chloroplast genome sequences of two Trillium species. AoB Plants 8:lw015 10.1093/aobpla/plw015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W. J., Wurdack K. J., Zimmer E. A., Weigt L. A., Janzen D. H. (2005). Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 8369–8374. 10.1073/pnas.0503123102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (1986). An examination of the “Zao-Xiu”, “Chong-Lou” and “Wang-Sun” from Chinese materia medica. Guihaia 6 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (1998). “The phylogeny of the genus Paris L,” in The Genus Paris L, ed. Li H. (Beijing: Science Press; ), 8–65. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Su B., Yang Y., Zhang Z. (2015). An assessment on the Rarely medical Paris plants in China with exploring the future development of its plantation. J. West China Forest. Sci. 44 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M., Drechsel O., Bock R. (2007). OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet. 52 267–274. 10.1007/s00294-007-0161-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C. L., Li H., Ouyang Z., Yang X., Qin L., Trangmar B. (2003). Strategies for agrobiodiversity conservation and promotion: a case from Yunnan, China. Biodivers. Conserv. 12 1145–1156. 10.1023/A:1023085922265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A., Pfeiffer W., Schwartz T. (2010). “Creating the CIPRES science gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees,” in Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop, New Orleans, LA, 1–8. 10.1109/GCE.2010.5676129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B. (1987). Paris-Part I. Plantman. 9 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B. (1988). Paris-Part II, Daiswa. Plantman. 10 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Bell C. D., Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E. (2007). Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 19363–19368. 10.1073/pnas.0708072104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Soltis P. S., Bell C. D., Burleigh J. G., Soltis D. E. (2010). Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 4623–4628. 10.1073/pnas.0907801107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock C. J., Waters D. L., Edwards M. A., Bowen S. G., Rice N., Cordeiro G. M., et al. (2011). Chloroplast genome sequences from total DNA for plant identification. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9 328–333. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaloo S. K., Kawano S. (1999). Molecular systematics of Trilliaceae II. Phylogenetic analyses of Trillium and its allies using sequences of rbcL and matK genes of cpDNA and internal transcribed spacers of 18S–26S nrDNA. Plant Species Biol. 14 75–94. 10.1046/j.1442-1984.1999.00009.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parks M., Cronn R., Liston A. (2009). Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol. 7:1 10.1186/1741-7007-7-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. K., Jain M. (2012). NGS QC Toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS ONE 7:e30619 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H., Brinkmann H., Lavrov D. V., Littlewood D. T. J., Manuel M., Wörheide G., et al. (2011). Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol. 9:e1000602 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. (2008). jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25 1253–1256. 10.1093/molbev/msn083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas A., Carroll S. B. (2005). More genes or more taxa? The relative contribution of gene number and taxon number to phylogenetic accuracy. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 1337–1344. 10.1093/molbev/msi121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhsam M., Rai H. S., Mathews S., Ross T. G., Graham S. W., Raubeson L. A., et al. (2015). Does complete plastid genome sequencing improve species discrimination and phylogenetic resolution in Araucaria? Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15 1067–1078. 10.1111/1755-0998.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schattner P., Brooks A. N., Lowe T. M. (2005). The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 W686–W689. 10.1093/nar/gki366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Lickey E. B., Schilling E. E., Small R. L. (2007). Comparison of whole chloroplast tgenome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. Am. J. Bot. 94 275–288. 10.3732/ajb.94.3.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57 758–771. 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtajan A. (1983). A revision of Daiswa (Trilliaceae). Brittonia 35 255–270. 10.2307/2806025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triplett J. K., Clark L. G., Fisher A. E., Wen J. (2014). Independent allopolyploidization events preceded speciation in the temperate and tropical woody bamboos. New Phytol. 204 66–73. 10.1111/nph.12988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. H., Niu H. M., Zhang Z. Y., Hu X. Y., Li H. (2015). Medicinal values and their chemical bases of Paris. China J. Chin. Mat. Med. 40 833–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens J. J. (2003). Missing data, incomplete taxa, and phylogenetic accuracy. Syst. Biol. 52 528–538. 10.1080/10635150390218330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. V., Miller J. T., Small I., Nevill P. G., Boykin L. M. (2016). Integration of complete chloroplast genome sequences with small amplicon datasets improves phylogenetic resolution in Acacia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 96 1–8. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman S. K., Jansen R. K., Boore J. L. (2004). Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20 3252–3255. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. B., Li D. Z., Li H. T. (2014). Highly effective sequencing whole chloroplast genomes of angiosperms by nine novel universal primer pairs. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14 1024–1031. 10.1111/1755-0998.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. B., Tang M., Li H. T., Zhang Z. R., Li D. Z. (2013). Complete chloroplast genome of the genus Cymbidium: lights into the species identification, phylogenetic implications and population genetic analyses. BMC Evol. Biol. 13:1 10.1186/1471-2148-13-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhai Y., Liu T., Zhang F., Ji Y. (2011). Detection of Valeriana jatamansi as an adulterant of medicinal Paris by length variation of chloroplast psbA-trnH region. Planta Med. 77 87–91. 10.1055/s-0030-1250072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.