Abstract

Past work on selective optimization and compensation (SOC) has focused on between-person differences and its relationship with global well-being. However, less work examines within-person SOC variation. This study examined whether variation over 7 days in everyday SOC was associated with happiness in a sample of 145 adults aged 22–94. Age differences in this relationship, the moderating effects of health, and lagged effects were also examined. On days in which middle-aged and older adults and individuals with lower health used more SOC, they also reported greater happiness. Lagged effects indicated lower happiness led to greater subsequent SOC usage.

Keywords: selective optimization with compensation, well-being, daily diary, midlife, older adults

Older adults typically report higher well-being compared to middle-aged adults, despite possessing comparatively fewer cognitive, physical, and social resources (George, 2010). As the percentage of middle-aged and older adults in the United States population rises, examining what behaviors contribute to— and can help increase— well-being at different ages is key (Lachman, 2004; Lachman, Teshale, & Agrigoroaei, 2015). However, it is less clear what behaviors might help individuals achieve higher well-being—for instance, what behaviors might help increase well-being in midlife, a time period with multiple demands on resources. Selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) strategies may be a potential avenue for improving well-being across ages, as suggested by a recent review (López Ulloa, Møller, & Sousa-Poza, 2013).

SOC is a model developed by Baltes and Baltes (1990) of regulatory strategies associated with successful aging (for a review, see Riediger, Li, & Lindenberger, 2006, p. 295). The SOC model includes four components: elective selection (choosing a particular goal or set of goals to pursue), loss-based selection (selecting goals in the face of resource loss), optimization (enhancing or acquiring resources in order to achieve a goal), and compensation (reallocating resources towards another goal to maintain functioning at a specific level). Different components of SOC can have differential effects on well-being (e.g., elective and loss-based selection relate to fewer job stressors [Baltes & Heydens-Gahir, 2003]; optimization and compensation relate to well-being indicators [Freund & Baltes, 1998]). However, the SOC model proposes that using all components is most effective (Freund & Baltes, 2002) in helping adults utilize cognitive, physical, and social resources; SOC components examined in tandem connect to well-being (Freund & Baltes, 2002), and can together contribute to successful aging (Freund, 2008).

A review by Freund (2008) suggests that using SOC could help individuals use resources effectively, and thereby improve well-being. SOC usage correlates with well-being indicators in younger adults (Wiese, Freund, & Baltes, 2000), and could be beneficial to individuals across adulthood (Wiese & Freund, 2000). Using more SOC in work and family domains is connected to reporting fewer work and family stressors, and thus lower work/family conflict, cross-sectionally (Baltes & Heydens-Gahir, 2003). SOC usage is resource-intensive, and SOC is less commonly used in old-old age compared to young-old age (Freund & Baltes, 2002). Older adults with more resources report using more SOC than older adults with fewer resources (Lang, Rieckmann, & Baltes, 2002). Some work (Freund & Baltes, 2002) suggests that selection increases and compensation decreases with age, and found evidence for a quadratic relationship between SOC and age, which suggests a peak in midlife.

Using SOC may benefit middle-aged and older adults in different ways. In midlife, SOC may be a useful strategy to manage high demand on resources. Middle-aged adults often experience multiple stressors; they may be in caregiving roles for both children and older relatives, and may need to determine how best to balance home and job responsibilities (Marks, 1998; Grzywacz, 2000; Lachman, Teshale, & Agrigoroaei, 2015). An increased level of demand, along with evidence that well-being is lower in midlife (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008), suggests that the effectiveness of resource management strategies such as SOC may be highly relevant to middle-aged adults. For older adults, SOC may be beneficial as a strategy to effectively manage limited resources (Freund & Baltes, 1998). Using SOC has been shown to buffer memory from the effects of cognitive decline (Hahn & Lachman, 2015, p. 11); as older adults experience decline in domains such as memory and processing speed (Hultsch, Hertzog, Small, & Dixon, 1999; Salthouse, Atkinson, & Berish, 2003), SOC usage may help minimize the effects of resource loss. However, few studies have looked at variation in SOC usage on a daily level across a wide age range. Examining how individuals across adulthood vary in their everyday SOC usage from day to day, and whether daily variation connects to well-being, can address questions about age differences in the adaptive value of using SOC. In spite of SOC’s potential to improve or maintain well-being over time, however, few studies record multiple assessments of everyday SOC usage. Past longitudinal work that has examined SOC usage (e.g., Jopp & Smith, 2006) often uses data from long-term studies, measuring SOC change over years. In contrast, methods that capture short-term change, such as experience sampling (Scollon, Kim-Prieto, & Diener, 2003) and diary methods, offer a more targeted method of examining within-person relationships between SOC and well-being. A few studies (e.g., Yeung & Fung, 2009; Schmitt, Zacher, & Frese, 2012; Zacher, Chan, Bakker, & Demerouti, 2015) have examined daily SOC usage in the work domain. To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between daily usage of general SOC strategies and well-being across adulthood.

The goal of the present study was to examine the relationship between general SOC strategy usage and happiness, a component of well-being, and how this relationship varied on a daily basis across ages. We tested whether within-person changes in daily SOC usage were related to happiness, using a daily diary method. Past research (Schmitt, Zacher, & Frese, 2012) found positive daily relationships between SOC and well-being indicators in the work domain, suggesting that using regulatory strategies like SOC in response to challenges can help buffer against immediate negative effects. Thus, we predicted that on days when individuals reported higher levels of SOC usage, they would also report higher happiness. We also examined the direction of the SOC-happiness relationship over time using lagged models. We predicted a positive lagged relationship of SOC to happiness, based on theory (Baltes & Baltes, 1990) that proposes individuals who use SOC will show successful aging. We examined how resource level affected the relationship between SOC and well-being. Based on work that suggests SOC may help individuals effectively manage limited resources (Freund & Baltes, 1998), we predicted that individuals with lower health would show a positive relationship between SOC and happiness. We also predicted that age would moderate the daily relationship between SOC usage and happiness. Based on findings of a between-person relationship between general SOC usage and well-being in older adults (Freund & Baltes, 1998), we predicted that older adults would show a positive daily relationship between SOC usage and happiness. Based on research indicating middle-aged adults endorse SOC strategies (Freund & Baltes, 2002), we predicted middle-aged adults, who typically have greater demands that necessitate SOC usage, and would likely have the cognitive resources to facilitate SOC usage, would show a positive daily relationship between SOC usage and happiness. Research suggests SOC is most relevant for individuals experiencing high demand on limited resources (Riediger, Li, & Lindenberger, 2006; Yeung & Fung, 2009). Because younger adults may have more cognitive and physical resources compared to middle-aged and older adults to address challenges, and relatively fewer demands on their resources, using strategies effectively to manage resources may be less critical to younger adults’ well-being. Thus, we predicted they would show a weaker relationship between well-being and SOC.

Method

Participants

Participants (N =145, 60% female) aged 22 to 94 (M = 50.53, SD = 19.17) were recruited from regions across the United States, using a design stratified by age, sex, and education. Adults aged 39 and under (n = 45) were defined as younger; adults aged 40–59 (n = 53) were defined as middle-aged; adults aged 60 and over (n = 46) were defined as older. The sample had an average of 15.16 years of education (SD = 2.47). Participants were recruited using signs in public locations and local newspaper advertisements for the Daily Experiences and Memory Study.

Materials

Study materials were included as part of a larger background questionnaire and set of daily diaries sent by mail. The measures used for this study are described below.

Demographic questionnaire

Participants reported their age, sex, level of education, and employment status. Educational status was reported on a 12-item categorical scale. Categorical status (ex. “Completed high school”) was converted into a continuous variable indicating number of years of education. Employment status was reported on a 12-item categorical scale. A “Work status” dichotomous variable was created where individuals who were currently working or self-employed were given a score of 1, and all other individuals were given a score of 0.

General health

General health was assessed using a background questionnaire. Participants rated on a scale from 1 (“a lot”) to 4 (“not at all”) how much their health limited them in completing a set of daily activities. These daily activities included lifting or carrying groceries; bathing or dressing oneself; climbing several flights of stairs; climbing one flight of stairs; bending, kneeling or stooping; walking more than a mile; walking several blocks; walking one block; and moderate activity (e.g. bowling, vacuuming). Scores were averaged across the 9 items; a higher score indicated better health (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

Global and daily well-being

Global well-being was assessed with an 11-point scale of life satisfaction, where 0 represented “the worst possible life overall” and 10 represented “the best possible life overall.” Participants rated their life overall currently (i.e., “these days”) (Röcke & Lachman, 2008). Daily well-being was assessed with a modified version of the Fordyce Emotions Questionnaire (Fordyce, 1988), which measured self-reported happiness. The questionnaire was modified to read: In general, how happy or unhappy did you feel today? Happiness was examined because, as an affective component of well-being, we expected it to be more likely to vary over a short time period than life satisfaction, an evaluative component of well-being (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999).

Selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) questionnaires

Daily SOC strategies were assessed with a modified version of Freund and Baltes’ SOC Questionnaire (2002) that asked how often the participant used SOC strategies on that day. Each SOC component was assessed with one item: “I committed myself to one or two important goals” (elective-based selection), “When I couldn’t do something as well as I used to, I thought about my priorities and what exactly is important to me” (loss-based selection), “I made every effort to achieve a given goal” (optimization), and “When things didn’t go as well as they used to, I kept trying other ways until I could achieve the same result I used to” (compensation). Participants indicated on a six-point scale how representative these strategies were of their experience that day. Scores could range from one to six, with higher scores indicating greater SOC strategy use. All four items were averaged to form a composite SOC score (Freund & Baltes, 2002). A minimum of two answered questions was required for score calculation; 86.2% of participants filled out at least two items on all seven diaries. For each daily SOC score, with four items per day, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .72, for Day 1 items, to .84 for Day 7 items. Cronbach’s alpha for SOC items over all seven days (28 items in total) was .92. We also administered a 12-item global SOC questionnaire at the beginning of the study (adapted from Freund & Baltes, 2002) that assessed how often individuals used SOC strategies long term. Each SOC component was assessed using three dichotomous items each, for a total of 12 items measuring global SOC usage. Items were recoded so that for all items, a score of two indicated SOC use, and a score of one indicated no SOC use. Scores for the 12 items were averaged to create a total score ranging from one (indicating no SOC strategies were selected) to two (indicating all of the SOC strategies were selected, i.e. high global SOC usage). Global SOC usage was measured as an average of all four SOC components, in line with past work (Jopp & Smith, 2006). Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was .63. A minimum of two completed items was required for score calculation; 91.7% of participants answered all 12 items. The highest number of missing items was six (one participant).

Design and Procedures

Participants were contacted via telephone and screened for eligibility with a short mental status questionnaire (Pfeiffer, 1975). Participants were deemed eligible if they had two or fewer errors. Eligible participants completed a cognitive assessment and were mailed a package with a background questionnaire and seven daily diaries. Participants filled out the background questionnaire and mailed it back to the research lab in a stamped and addressed envelope. The next day, participants began the first of seven consecutive daily protocols. Each night, they filled out daily SOC and well-being questionnaires, as well as other questionnaires not included in the current analysis. Participants filled out four daily SOC items and one happiness item. A researcher called the participant each night to check in and remind the participant to fill out the diary questionnaires. To reduce participant burden, as few questions as possible were asked during the phone call. SOC and happiness questions were answered using self-report in the evening, so that responses incorporated the entire day’s events. 92.4% of participants mailed back all 7 diaries, 4.8% mailed back 6 diaries, and 1.4% mailed back 4 diaries.

Data Analysis

All models controlled for gender, grand-mean centered years of education, working status, and grand-mean centered general self-reported health. Education and general health were included as covariates, since they have been used as markers of personal resources (Diehl, Willis, & Schaie, 1995) and are related to well-being. Missing data were not imputed; a restricted maximum likelihood estimation method was used to incorporate all available data. Participants who returned all 7 diaries (n = 134) were compared to those who returned 6 or fewer diaries (n = 11). There were no significant differences between the two groups on mean age, mean years of education, mean general health score, working distribution, or gender distribution.

Day-to-day differences in the relationship between SOC usage and the dependent variable of happiness over 7 days were examined using multilevel modeling. A restricted maximum likelihood estimation method was used to account for relatively small sample sizes (Wickham & Knee, 2013; Hahn & Lachman, 2015). First, an unconditional model was run; this model examined only random effects of intercept and day, to examine the amounts of between-person and within-person variability in happiness across 7 days. 46.2% of the variance in happiness was explained by within-person factors, and 53.8% was explained by between-person factors. Additionally, 51.7% of the variance in daily SOC score across 7 days was explained by within-person factors, and 48.3% was explained by between-person factors. Next, a model was run to examine whether reporting higher SOC usage on a given day compared to an individual’s week-average SOC usage was associated with higher happiness on that day. Level 1 within-person variables were daily happiness and daily SOC score. Daily SOC scores were centered around the individual’s week-average SOC score, and thus measured an individual’s day-to-day variability in SOC usage compared to their 7-day average. Level 2 between-person variables included gender, years of education, working status, general health, age, and age2. The model examined the moderating effects of age on this within-person relationship by including grand mean-centered age and age2 terms, and Age x SOC and Age2 x SOC interaction terms, at Level 2. Age was continuous, and interactions were graphed using values +/− 1 SD from mean age. Covariates (gender, education, working status, and health) were included in the model at Level 2, as shown below:

To examine the direction of the relationship between daily SOC and happiness over the week, we examined the lagged relationship of SOC to happiness by creating a model that included SOC score on the previous day as an independent variable, and happiness on the current day as the dependent variable. We also examined the lagged relationship of happiness to SOC, by creating a model that included happiness on the previous day as an independent variable, and SOC score on the current day as the dependent variable. For both models, the value of the dependent variable on the previous day was included as a control. These models examined how lagged SOC affected change in happiness, and how lagged happiness affected change in SOC.

Results

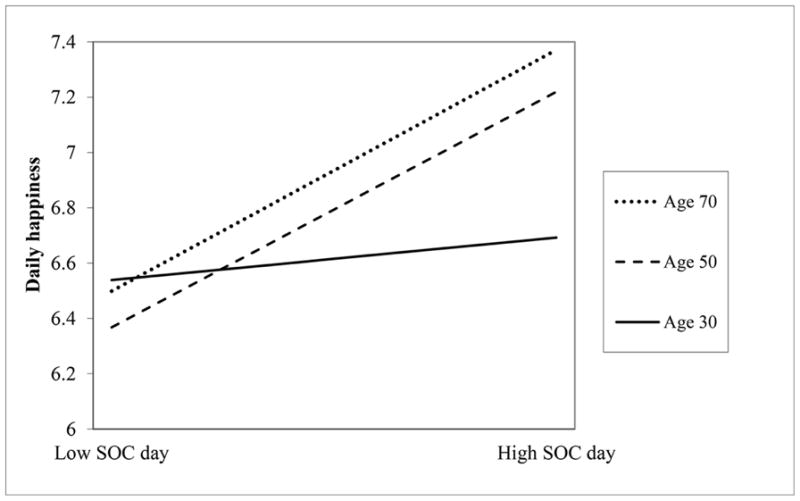

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables are reported in the Supplementary Materials. Global SOC did not predict outcome measures or affect the significance of other predictors, and was trimmed from the model. Baseline life satisfaction significantly predicted daily happiness, but did not lead to a change in significance level or direction of results for variables of interest, and was not included in the final model. Within-person daily SOC score significantly predicted daily happiness, in line with predictions (Table 1).1 In line with predictions, Age x SOC and Age2 x SOC interaction terms were significant. Middle-aged and older adults, but not younger adults, showed a significant positive day-to-day relationship between SOC usage and happiness (Figure 1). Controlling for baseline memory did not affect results. To examine the role of health in the relationship between SOC and happiness, a model was created that included a Health x SOC interaction term. This interaction term was significant (β = −.2064, p < .01) suggesting that on days in which less healthy individuals used SOC, they reported higher happiness. A three-way Age x Health x SOC interaction was nonsignificant. Lagged analyses indicated a lagged relationship of happiness to SOC (β = −.0891, p < .01), suggesting that lower happiness on the previous day was related to higher SOC usage on the subsequent day. The lagged relationship of SOC to happiness was nonsignificant. (Tables for these results are included in the Supplementary Materials.)

Table 1.

Fixed Effects Parameter Estimates For Multilevel Model Predicting Day-To-Day Happiness for Full Sample

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 6.79 | .55 | <.001 | [5.71, 7.87] |

| Time | 0.017 | .027 | .53 | [−.036, .070] |

| Age | .0083 | .0079 | .29 | [−.0073, .024] |

| Age2 | −.00005 | .00039 | .89 | [−.00082, .00071] |

| Gender | −.0054 | 0.28 | .98 | [−.56, .55] |

| Years of education | .12 | .064 | .073 | [−.011, .24] |

| General health * | .63 | .21 | .004 | [.203, 1.047] |

| Working * | −.61 | .30 | .043 | [−1.20, −.018] |

| WP SOC score * | .35 | .085 | <.001 | [.18, .52] |

| Two-way interaction effects | ||||

| Age X WP SOC score * | 0.0077 | .0032 | .0152 | [.0015, .014] |

| Age2 X WP SOC score * | −.00038 | .00017 | .028 | [−.00072, −.00004] |

| Covariance parameters | ||||

| Intercept variance | 2.94 | .55 | <.001 | |

| Intercept/slope variance | −.14 | .071 | .056 | |

| Slope variance | .023 | .012 | .031 | |

| Residual | 1.96 | .11 | <.001 | |

Note: WP = within person; SOC = selection, optimization, and compensation strategy usage. Age, Age2, years of education and general health centered around grand mean.

Figure 1.

Relationship between day-to-day SOC usage and happiness as a function of age.

Note: SOC = selection, optimization, and compensation strategy usage. For purposes of illustration, low SOC day = −1.5 SD from mean of within-person SOC score; high SOC day = +1.5 SD from mean of within-person SOC score. Mean of within-person SOC score = person-mean SOC score, SD = .8089. Continuous variables were used in the analysis; coefficients for centered age and age2 are reported. Mean age = 50.53, SD = 19.17. Younger age = mean −1SD of age. Middle age = mean age. Older age = mean +1SD of age. Graph centered at grand mean of general health and years of education.

Discussion

In line with predictions, on days in which they used more selection, optimization, and compensation strategies compared to their week-average, individuals reported greater happiness. Older and middle-aged adults showed a significant positive relationship between daily SOC usage and happiness. Thus, SOC seems to be an important strategy of everyday resource management in both middle and older age, with implications for well-being. In addition, lagged results suggested that when individuals reported lower happiness, they reported higher SOC on the next day. This suggests individuals may respond to circumstances of lower well-being by adopting SOC strategies.

This study is a first step in examining the relationship between variation in everyday SOC strategy usage and well-being. Though global SOC was not directly correlated with well-being, global SOC was correlated with weekly average SOC, which was in turn correlated with well-being. This suggests that the relationship between SOC and well-being may be more apparent in a daily context. However, one limitation was that our global measure of SOC did not capture the extent to which individuals identified with using a given SOC component. We found lower happiness predicted an increase in SOC, and a positive daily relationship between SOC and happiness, but no relationship between lagged SOC and happiness. This suggests that individuals may use SOC when things are not going well, and that SOC is associated with concurrent but not subsequent daily happiness. However, the study design does not allow us to infer causality.

The effortful nature of SOC should also be taken into account, especially when analyzing SOC usage in older adults. Older adults with low health or cognitive functioning may be less likely to use effortful strategies such as SOC (Freund & Baltes, 2002), despite the potential benefits. Future studies could examine SOC interventions in older adults who vary in resource levels, to investigate ways to balance the cognitive demands of SOC with its benefits. Results suggested SOC had a stronger effect on lower-health individuals; research could investigate whether increasing individuals’ SOC usage shows stronger effects on well-being for individuals with fewer resources, such as those with low education or health. Future research could investigate whether SOC interventions could be developed specifically for those with fewer resources, as seen in Unger, Sonnentag, Niessen, and Kuonath (2015), and Wiese and Heidemeier (2012). This approach can help identify those who would benefit most from SOC.

We noted that younger adults did not show a relationship between SOC usage and well-being. This may have been due to younger adults’ level of experience in employing SOC strategies compared to middle-aged and older adults. If younger adults, who typically possess more cognitive resources compared to middle-aged and older adults, experience fewer significant demands on resources, they may have fewer opportunities to practice using SOC. They may be less experienced, and thus less effective, in using SOC to help improve well-being. Future work could examine this question through testing SOC interventions for younger adults experiencing high resource demand, and examining whether the benefits of SOC usage for well-being become more apparent for younger adults as they gain experience in using SOC.

The results of this study indicate that everyday SOC usage is related to same-day happiness. The tradeoff between SOC’s effortful nature and its potential to contribute to well-being in lower-resource individuals is a promising avenue of future study, as is the question of whether increasing SOC strategy use results in higher well-being. This work builds on previous research by showing that day-to-day general SOC usage is related to higher well-being in middle and older age, and by showing for the first time a lagged relationship of happiness to SOC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grant R01AG17920 to Margie E. Lachman.

Footnotes

All four SOC items showed similar within-person variability. Examined separately, all items except loss-based selection showed a significant relationship to daily happiness; loss-based selection showed a marginal (p = .05) relationship. Item-total correlations indicated removing any one item from the composite score reduced Cronbach’s alpha.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Portions of this work were presented at the 2014 Society for Personality and Social Psychology Preconference on Happiness and Well-Being in February 2014 in Austin, TX, and the Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting, November 2014, in Washington, D.C.

References

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM, editors. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 1–34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes BB, Heydens-Gahir HA. Reduction of work-family conflict through the use of selection, optimization, and compensation behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:1005–1018. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1733–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Willis SL, Schaie KW. Everyday problem solving in older adults: Observational assessment and cognitive correlates. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:478–491. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.10.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce MW. A review of research on the happiness measures: A sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research. 1988;20:355–381. doi: 10.1007/bf00302333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM. Successful aging as management of resources: The role of selection, optimization, and compensation. Research in Human Development. 2008;5:94–106. doi: 10.1080/15427600802034827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Baltes PB. Selection, optimization, and compensation as strategies of life management: Correlations with subjective indicators of successful aging. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:531–543. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Baltes PB. Life-management strategies of selection, optimization and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:642–662. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Still happy after all these years: research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65:P331–P339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz J. Work-family spillover and health during midlife: is managing conflict everything? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14:236–243. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.4.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EA, Lachman ME. Everyday experiences of memory problems and control: The adaptive role of selective optimization with compensation in the context of memory decline. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2015;22:25–41. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2014.888391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, Dixon RA. Use it or lose it: Engaged lifestyle as a buffer of cognitive decline in aging? Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:245–263. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.14.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopp D, Smith J. Resources and life-management strategies as determinants of successful aging: On the protective effect of selection, optimization, and compensation. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:253–265. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Teshale SM, Agrigoroaei S. Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2015;39:20–31. doi: 10.1177/0165025414533223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR, Rieckmann N, Baltes MM. Adapting to aging losses: do resources facilitate strategies of selection, compensation, and optimization in everyday functioning? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:P501–P509. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López Ulloa BF, Møller V, Sousa-Poza A. How does subjective well-being evolve with age? A literature review. Journal of Population Ageing. 2013;6:227–246. doi: 10.1007/s12062-013-9085-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marks NF. Does it hurt to care? Caregiving, work-life conflict, and midlife well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60:951–966. doi: 10.2307/353637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger M, Li S, Lindenberger U. Selection, optimization, and compensation as developmental mechanisms of adaptive resource allocation: review and preview. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 289–313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Röcke C, Lachman ME. Perceived trajectories of life satisfaction across past, present, and future: Profiles and correlates of subjective change in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:833–847. doi: 10.1037/a0013680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, Atkinson TM, Berish DE. Executive functioning as a potential mediator of age-related cognitive decline in normal adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:566–594. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt A, Zacher H, Frese M. The buffering effect of selection, optimization and compensation strategy use on the relationship between problem solving demands and occupational well-being: a daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2012;17:139–149. doi: 10.1037/a0027054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Kim-Prieto C, Diener E. Experience sampling: promises and pitfalls, strengths and weaknesses. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2003;4:5–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1023605205115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unger D, Sonnentag S, Niessen C, Kuonath A. The longer your work hours, the worse your relationship? The role of selective optimization with compensation in the associations of working time with relationship satisfaction and self-disclosure in dual-career couples. Human Relations. 2015;68:1889–1912. doi: 10.1177/0018726715571188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham RE, Knee CR. Examining temporal processes in diary studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013;39:1184–1198. doi: 10.1177/0146167213490962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese BS, Freund AM. The interplay of work and family in young and middle adulthood. In: Heckhausen J, editor. Motivational psychology of human development: developing motivation and motivating development. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 233–249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese BS, Freund AM, Baltes PB. Selection, optimization, and compensation: an action-related approach to work and partnership. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2000;57:273–300. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese BS, Heidemeier H. Successful return to work after maternity leave: Self-regulatory and contextual influences. Research in Human Development. 2012;9:317–336. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2012.729913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung DY, Fung HH. Aging and work: how do SOC strategies contribute to job performance across adulthood? Psychology & Aging. 2009;24:927–940. doi: 10.1037/a0017531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacher H, Chan F, Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Selection, optimization, and compensation strategies: interactive effects on daily work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2015;87:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.