Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the change in the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and prescribing of stimulants to children 4 to 5 years old after release of the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics guideline.

METHODS:

Electronic health record data were extracted from 63 primary care practices. We included preventive visits from children 48 to 72 months old receiving care from January 2008 to July 2014. We compared rates of ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing before and after guideline release using logistic regression with a spline and clustering by practice. Patterns of change (increase, decrease, no change) were described for each practice.

RESULTS:

Among 87 067 children with 118 957 visits before the guideline and 56 814 with 92 601 visits after the guideline, children had an ADHD diagnosis at 0.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7% to 0.8%) of visits before and 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8% to 0.9%) after guideline release and had stimulant prescriptions at 0.4% (95% CI, 0.4% to 0.4%) of visits in both periods. A significantly increasing preguideline trend in ADHD diagnosis ended after guideline release. The rate of stimulant medication use remained constant before and after guideline release. Patterns of change from before to after the guideline varied significantly across practices.

CONCLUSIONS:

Release of the 2011 guideline that addressed ADHD in preschoolers was associated with the end of an increasing rate of diagnosis, and the rate of prescribing stimulants remained constant. These are reassuring results given that a standardized approach to diagnosis was recommended and stimulant treatment is not first-line therapy for this age group.

What’s Known on This Subject:

In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics updated their attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD) Clinical Practice Guideline to include, for the first time, recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of preschool-age children, but little is known about the impact of this guideline.

What This Study Adds:

Release of the 2011 guideline, which standardized ADHD diagnosis and treatment of preschool-age children, was associated with the end of an increasing trend in preschool ADHD diagnosis. The rate of prescribing stimulants to preschoolers remained constant.

Preschool attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common condition with substantial morbidity that is often managed in primary care and often treated with medication. Parents of >30% of preschool-age children seen in primary care report behavioral concerns.1 Such behaviors may have meaningful consequences for children in this age group, with an estimated 6.7 per 1000 expelled nationally from preschool or child care.2 For pediatric clinicians, these behaviors may prompt evaluation for psychiatric or behavioral disorders, especially ADHD, and the initiation of psychotropic medication.3 In fact, 1 in 3 children diagnosed with ADHD is diagnosed during preschool years,4 and 47% of preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD are treated with medication alone or in combination with behavior therapy.5 Reflecting the degree of impairment associated with ADHD in this group, preschool children with ADHD are more likely to be in special education programs, have unintentional injuries, be considered disruptive, and be less well-liked than other children.6,7 In addition, preschool ADHD usually persists into later childhood; >60% of preschoolers diagnosed with only the hyperactive or inattentive and >80% of those with combined type ADHD will continue to meet criteria for ADHD at age 7 years.8,9 As a result, decisions about diagnosis and treatment in this age group often have long-lasting impacts on children.

Still, given the possibility of overlap between normal behavior and behaviors associated with ADHD10 and the relative lack of trials in this age group, pediatricians and the public have been concerned about the potential for excessive diagnosis and medication treatment of preschool-aged children. Before 2011, no American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline existed to help pediatricians diagnose or treat ADHD among preschoolers. To address these concerns and standardize care by using the best available medical evidence, the AAP in 2011 added guidance on the diagnosis and treatment of preschool ADHD (children 4 and 5 years of age) to their clinical practice guidelines.11 This standardization of care is important given the known variability in ADHD management across sites.12–17 In terms of diagnosis, the new guideline recommends that “the primary care clinician should initiate an evaluation for ADHD for any child 4 through 18 years of age who presents with academic or behavioral problems and symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity” and cite increased evidence that an appropriate diagnosis is possible in the preschool-age group.10 For treatment, the guideline specifies, “For preschool-aged children (4–5 years of age), the primary care clinician should: 1) prescribe evidence-based parent- and/or teacher-administered behavior therapy as the first line of treatment (quality of evidence A/strong recommendation) and 2) may prescribe methylphenidate if the behavioral interventions do not provide significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continuing disturbance in the child’s function.”18

Few data are available on the association of guideline release with patterns of diagnosis and treatment in preschool children with ADHD. A 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report using administrative data found no significant change in medication prescribing among preschoolers and toddlers covered by employee-sponsored health insurance before compared with after guideline release.19 However, this report did not examine changes at the practice level, differences that are especially important because practices are the microsystems through which care is delivered.20 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report also primarily considered children age 2 to 5 years, although the guideline specifically issued recommendations only for those 4 to 5 years of age. To address patterns of diagnosis and treatment of children 4 to 5 years with varying insurance at a wide range of practices,21 the objective of this study was to examine changes in rates of ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing to children aged 48 to 72 months (4 to 5 years) old after publication of the 2011 ADHD practice guideline and to examine variability in patterns of change across primary care practices.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted among practices in the Comparative Effectiveness Research Through Collaborative Electronic Reporting (CER2) Consortium.21 CER2 is a “super-network” composed of 8 electronic health record (EHR)-based research networks, including the Electronic Pediatric Research in Office Settings (ePROS) network of the AAP,22 the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the American Academy of Family Physicians Electronic National Quality Improvement and Research Network, the MetroHealth System/Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, the Boston Medical Center/Boston Health Net, the Allied Physicians Group, and Eskenazi Health. The network includes a racially, ethnically, and economically diverse group of >1.2 million children seen by >2000 primary care providers at 222 urban, suburban, and rural practices and clinics.

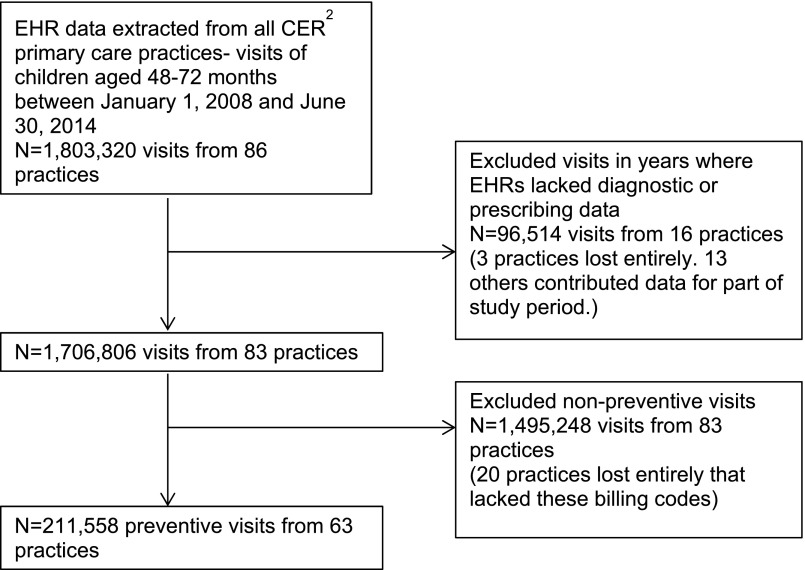

In this study, EHR data were extracted from 86 primary care practices within CER2 (Fig 1). We extracted all visits by children aged 48 to <72 months attending a participating practice between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2014 (N = 1 803 320 visits). We excluded certain years of data from some sites where EHRs lacked diagnostic or prescribing data (N = 96 514 visits from 16 practices). To focus on visits where all chronic conditions, including ADHD and its medication treatment, would be expected to be reviewed and updated, we restricted analysis to preventive visits by identifying visits that had a preventive health evaluation and management code (993nn). Twenty practices lacking these billing codes were excluded. After exclusions, the final study sample included 211 558 visits from 143 881 children at 63 primary care practices. In a sensitivity analysis, we expanded the definition of a preventive visit to include International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code V20.2, for well child visits, and found similar results.

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion of primary care visits of 48- to 72-month-old children from electronic health record data.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes included evidence of an ADHD diagnosis, identified by an ICD-9 code of 314.0 to 314.9, and evidence of a stimulant medication prescription, identified by Generic Product Identifier, National Drug Code, and free text search, at each visit.14,23 Stimulants were classified as methylphenidate or amphetamine compounds.

Guideline Implementation

The exposure of interest in this study was implementation of the ADHD guideline on October 1, 2011. The preguideline period was defined from January 1, 2008 to September 30, 2011 (45 months), and the postguideline period was defined from October 1, 2011 to June 30, 2014 (33 months).

Covariates

Patient-level covariates included child gender and age (48–60 months or 61–72 months). Race and ethnicity were not included in our analysis because of high levels of missingness (21.4% for race and 13.9% for ethnicity) that were highly practice dependent, a situation that precluded formal imputation. Additional covariates included whether the child had any comorbidities or received any other psychotropic medications. A comorbidity was defined as having an ADHD diagnosis and any of the following ICD-9 codes: anxiety (300.00–300.29, 301.4), autism or pervasive developmental disorder (299.00–299.99), bipolar disorder (296.00–296.10, 296.36–296.89), conduct disorder (312.00–312.89), depression (311, 296.20–296.35), developmental delay (315), oppositional defiant disorder (313.81), schizophrenia (295.00–295.99), and tic disorder (307.2–307.29, 333.3). Polypharmacy was defined as receiving a stimulant and any of the following classes of psychotropic medication at the same visit: α-agonists (clonidine and guanfacine), antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics), anxiolytics (benzodiazepines, others), mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, anticonvulsants, lithium), second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, others), and elective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (atomoxetine). In a sensitivity analysis, we explored the role of season and found no seasonal pattern in diagnosis or prescribing.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportion of visits at which an ADHD diagnosis or stimulant prescription was received during the preguideline and postguideline periods. By using logistic regression with a linear spline with a knot at the time of guideline release, we compared the trajectories of ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing in the 45 months before and the 33 months after guideline release. A separate model estimated the log odds of stimulant prescription among those diagnosed with ADHD. All models adjusted for patient age and used robust variance estimates to account for clustering by primary care practice.

Next, we examined variation between primary care practices in diagnosis and prescribing by using descriptive statistics (median, range, interquartile range). We then described practice-level change from before to after guideline implementation in both diagnosis and prescribing by calculating the proportion of practices with each of the following patterns: increase, no change, or decrease (by ≥0.1 percentage points). We tested whether the change from before to after the guideline varied significantly across practices by adding an interaction between practice and time to the models described above.

All analyses were conducted in Stata version 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the AAP Institutional Review Board. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board considered this study “not human subjects research.”

Results

Overall Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 211 558 primary care visits by 143 881 preschool-age children at 63 practices were included. The preguideline period included 118 957 visits among 87 067 children, whereas the postguideline period included 92 601 visits among 56 814 children. The gender distribution of the population remained constant over time, but the postguideline period had a higher percentage of visits with children aged 48 to 60 months (83% vs 71% in the preguideline period) and a lower proportion of visits with white (42% vs 48%) and Hispanic (10% vs 14%) children (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Study Population Before and After Release of the AAP Guideline for ADHD Management in 48- to 72-Month-Old Children, CER2 Consortium (N = 211 558 Primary Care Visits Among 143 881 Children)

| Preguideline Period (January 1, 2008–September 30, 2011: 45 mo) | Postguideline Period (October 1, 2011–June 30, 2015: 33 mo) | |

|---|---|---|

| N visits | 118 957 | 92 601 |

| N childrena | 87 067 | 56 814 |

| N children with ADHD | 776 | 598 |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 42 307 (48.6) | 27 756 (48.9) |

| Male | 44 760 (51.4) | 29 057 (51.1) |

| Age (at first visit) | ||

| 48–60 mo | 61 570 (70.7) | 47 039 (82.8) |

| 61–72 mo | 25 497 (29.3) | 9775 (17.2) |

| Race | ||

| White | 41 890 (48.1) | 24 085 (42.4) |

| Black or African American | 22 442 (25.8) | 15 846 (27.9) |

| Asian | 2329 (2.7) | 1741 (3.1) |

| Other race | 1090 (1.2) | 640 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 19 316 (22.2) | 14 502 (25.5) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 11 922 (13.7) | 5778 (10.2) |

| Visit characteristics | ||

| ADHD diagnosis | 848 (0.7) | 796 (0.9) |

| Stimulant prescription | ||

| Any stimulant | 467 (0.4) | 326 (0.4) |

| Methylphenidate | 291 (0.2) | 183 (0.2) |

| Amphetamine | 199 (0.2) | 159 (0.2) |

| Any comorbid diagnosisb | 212 (0.2) | 213 (0.2) |

| Developmental delay | 119 (0.1) | 110 (0.1) |

| Autism | 48 (<0.1) | 43 (<0.1) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 25 (<0.1) | 50 (<0.1) |

| Conduct disorder | 29 (<0.1) | 26 (<0.1) |

| Any polypharmacyc | 126 (0.1) | 87 (0.1) |

| α-Agonist | 101 (0.1) | 68 (0.1) |

| Second-generation antipsychotic | 25 (<0.1) | 16 (<0.1) |

| Antidepressant | 10 (<0.1) | 8 (<0.1) |

“N children” indicates the number of children who had their first visit in that period. The distribution of child characteristics changed slightly over time because some primary care practices were included in only 1 of the 2 periods and practice populations shifted.

Indicates an ADHD diagnosis (ICD-9 code 314.0–314.9) and any of the following additional diagnoses: anxiety (300.00–300.29, 301.4), autism (199.00–299.99), bipolar disorder (296.00–296.10, 296.36–296.89), conduct disorder (312.00–312.89), depression (311, 296.20–296.35), developmental delay (315), oppositional defiant disorder (313.81), pervasive developmental disorder (299), schizophrenia (295.00–295.99), and tic disorder (307.2–307.29, 333.3).

Indicates a prescription for a stimulant (either methylphenidate or amphetamine) and a prescription for any of the following medication classes: α-agonists (clonidine and guanfacine), antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics), anxiolytics (benzodiazepines, others), mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, anticonvulsants, lithium), second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, others), and elective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (atomoxetine).

Characteristics of Children With ADHD Diagnoses or Treated With Stimulant Medication

Children had an ADHD diagnosis at 0.7% of visits in the preguideline period and 0.9% in the postguideline period. The rate of stimulant prescribing was stable across periods (0.4%), as were rates of comorbid diagnoses and polypharmacy (Table 1). The demographic characteristics of children with a visit with an ADHD diagnosis or stimulant prescription are described in Table 2. ADHD diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions were more common in male than female children and in children aged 61 to 72 months compared with 48 to 60 months. Children with ADHD had a comorbid diagnosis at 25% (before guideline) and 27% (after guideline) of visits, most commonly developmental delay (14% in both periods), autism (6% before, 5% after), oppositional defiant disorder (3%, 6%) and conduct disorder (3% in both periods). Analyses of medication use revealed that the preschool-age children in the sample who were on stimulants received another psychotropic medication at 27% of visits in both periods. At visits by these children, the most prevalent medications used in combination with stimulants were α-agonists (22%, 21%), second-generation antipsychotics (5% in both periods), and antidepressants (2%, 3%).

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of 48- to 72-Month-Old Children With ADHD Diagnoses and Stimulant Prescriptions Before and After Guideline Implementation,a Visit-Level Characteristics

| ADHD Diagnosis | Stimulant Prescription | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preguideline Period | Postguideline Period | Preguideline Period | Postguideline Period | |

| N visits | 848 | 796 | 467 | 326 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 644 (75.9) | 615 (77.3) | 356 (76.2) | 254 (77.9) |

| Female | 204 (24.1) | 181 (22.7) | 111 (23.8) | 72 (22.1) |

| Age | ||||

| 48–60 mo | 289 (34.1) | 294 (36.9) | 112 (24.0) | 70 (21.5) |

| 61–72 mo | 559 (65.9) | 502 (63.1) | 355 (76.0) | 256 (78.5) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 324 (38.2) | 304 (38.2) | 211 (45.2) | 153 (46.9) |

| Black | 341 (40.2) | 348 (43.7) | 136 (29.1) | 110 (33.7) |

| Asian | 10 (1.2) | 9 (1.1) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) |

| Other race | 20 (2.4) | 19 (2.4) | 10 (2.1) | 5 (1.5) |

| Unknown race | 153 (18.0) | 116 (14.6) | 106 (22.7) | 56 (17.2) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 139 (16.4) | 121 (15.2) | 67 (14.4) | 56 (17.2) |

| Comorbid diagnosisb | 212 (25.0) | 213 (26.8) | 86 (18.4) | 50 (15.3) |

| Developmental delay | 119 (14.0) | 110 (13.8) | 43 (9.2) | 27 (8.3) |

| Autism | 48 (5.7) | 43 (5.4) | 20 (4.3) | 12 (3.7) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 25 (3.0) | 50 (6.3) | 11 (2.4) | 10 (3.1) |

| Conduct disorder | 29 (3.4) | 26 (3.3) | 13 (2.8) | 6 (1.8) |

| Polypharmacyc | 74 (8.8) | 52 (6.5) | 126 (26.7) | 87 (26.7) |

| α-Agonist | 62 (7.3) | 38 (4.8) | 101 (21.6) | 68 (20.9) |

| Second-generation antipsychotic | 12 (1.4) | 5 (0.6) | 25 (5.4) | 16 (4.9) |

| Antidepressant | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.4) | 10 (2.1) | 8 (2.5) |

Preguideline period: January 1, 2008–September 30, 2011; postguideline period: October 1, 2011–June 30, 2015.

Indicates an ADHD diagnosis (ICD-9 code 314.0–314.9) and any of the following additional diagnoses: anxiety (300.00–300.29, 301.4), autism (199.00–299.99), bipolar disorder (296.00–296.10, 296.36–296.89), conduct disorder (312.00–312.89), depression (311, 296.20–296.35), developmental delay (315), oppositional defiant disorder (313.81), pervasive developmental disorder (299), schizophrenia (295.00–295.99), and tic disorder (307.2–307.29, 333.3).

Indicates a prescription for a stimulant (either methylphenidate or amphetamine) and a prescription for any of the following medication classes: α-agonists (clonidine and guanfacine), antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics), anxiolytics (benzodiazepines, others), mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, anticonvulsants, lithium), second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, others), and elective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (atomoxetine).

Patterns of ADHD Diagnosis and Stimulant Medication Use Before and After Guideline Release

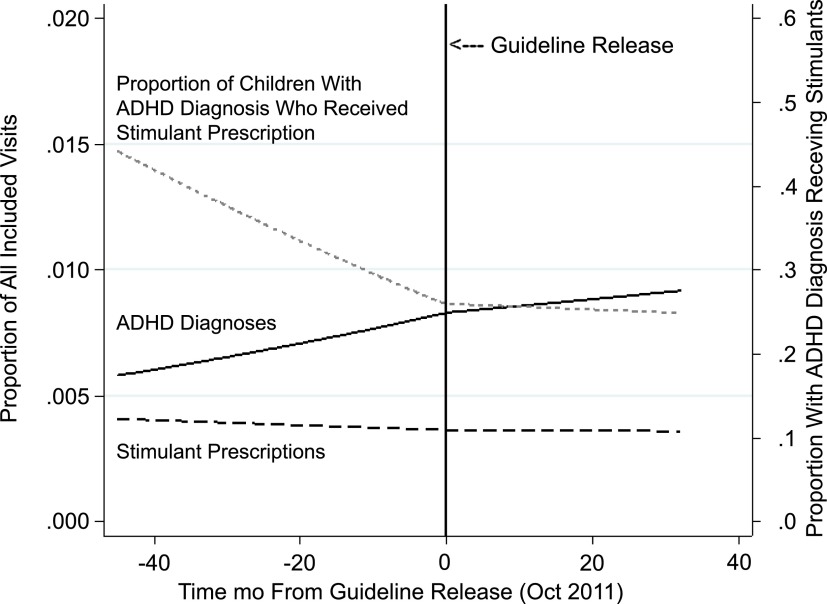

In the preguideline period, the trajectory of ADHD diagnosis increased slightly but significantly across practices (Fig 2, P = .01). However, the rate of ADHD diagnosis no longer increased significantly after guideline release (postguideline slope P = .6, indicating no difference from 0; change in slope from before to after guideline P = .4, indicating that change from before to after guideline was not significant). Levels of stimulant medication prescribing remained stable over time (preguideline slope P = .5, indicating no difference from 0; postguideline slope P = .9; change in slope P = .8, indicating no change in patterns of stimulant prescribing before versus after guideline release). Of note, the proportion of children with an ADHD diagnosis who received stimulants decreased significantly before guideline release (P < .001). After release, the proportion of children with an ADHD diagnosis who received stimulants did not change significantly over time (postguideline slope: P = .7).

FIGURE 2.

ADHD diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions before and after release of the AAP guideline for ADHD management in 48- to 72-month-old children (October 2011). Slopes were derived from logistic regression spline models with variances reflecting practice clustering.

Practice Variation

Table 3 displays the median and range of ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing at the primary care practice level before and after guideline release and highlights variability across sites. In addition to variability in rates of diagnosis and prescribing, we found that the change in the proportion of visits with an ADHD diagnosis or stimulant prescription from before to after guideline release varied significantly across practices (P < .001 for both; Table 4). The rate of diagnosis increased in 41% of practices, did not change in 19% of practices, and decreased in 24% of practices after release of the guideline. The rates of stimulant prescribing increased for 22% of practices, did not change for 21%, and decreased for 41% of practices. Ten practices (16%) had 0 eligible visits in 1 of the time periods, so change could not be assessed. These changes did not vary by urban, suburban, or rural practice setting, region of the United States, or network affiliation of practices.

TABLE 3.

Percentage of Visits at Practice for 48- to 72-Month-Old Children With ADHD Diagnosis or Stimulant Prescription in the Preguideline and Postguideline Periods

| Preguideline Period | Postguideline Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | IQR | Median | Range | IQR | |

| ADHD diagnosis, % | 0.4 | 0.0–24.1a | 0.2–1.0 | 0.7 | 0.0–10.4b | 0.3–1.4 |

| Stimulant prescription, % | 0.3 | 0.0–11.9a | 0.1–0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0–4.5 | 0.1–0.7 |

IQR, interquartile range.

The practice with the largest proportion of visits with ADHD diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions in the preguideline period had on-site mental health providers focused on diagnosis and management of ADHD. The next highest practice had ADHD diagnoses at 6.8% of visits.

The practice with the largest proportion of visits with ADHD diagnoses in the postguideline period had a small number of visits (N = 5 visits with ADHD out of 48). The next highest practice had ADHD diagnoses at 6.6% of visits.

TABLE 4.

Patterns of Change Between Preguideline and Postguideline Periods in ADHD Diagnosis and Stimulant Prescribing for 48- to 72-Month-Old Children Across Primary Care Practices

| Practice Patterns of Change From Preguideline to Postguideline Period (N = 63 Practices) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | No Change | Decrease | Not Applicablea | |

| ADHD diagnosis, N (%) | 26 (41.3) | 12 (19.0) | 15 (23.8) | 10 (15.9) |

| Stimulant prescription, N (%) | 14 (22.2) | 13 (20.6) | 26 (41.3) | 10 (15.9) |

For 10 practices, either the preguideline or postguideline period had 0 visits included in the sample, so change could not be assessed. P < .001 for both diagnosis and prescribing (calculated by including an interaction term between practice and time in logistic regression spline models). Increases or decreases reflect changes of ≥0.1 percentage point, respectively. This threshold was chosen because of low rates of diagnosis and prescribing in many practices.

Discussion

We investigated the impact of the 2011 AAP ADHD Clinical Practice Guideline on diagnosis and treatment among children 4 to 5 years of age. Although patterns at individual practices varied, overall results revealed that the diagnosis of ADHD in this age group was increasing before, but not after, the guideline release. Even so, rates of stimulant medication prescription remained stable throughout the study period. As a consequence of these patterns, before the guideline release but not after, children seen at included primary care sites were becoming less likely over time to receive stimulant medication if diagnosed.

A primary goal of clinical practice guidelines is to standardize care.24 In the case of preschool ADHD, such standardization might have resulted in an increasing trajectory in diagnosis of preschool children if pediatric clinicians had not previously been evaluating ADHD when an evaluation was warranted. Alternatively, a decrease in diagnosis could have occurred if clinicians were applying more rigorous standards to the diagnosis and therefore excluding certain children who might have previously been diagnosed or no change if a combination of these 2 patterns was occurring or if there was no change in the standard used. Our overall results indicate that the release of the 2011 guideline was associated with a stabilization of the rate of diagnosis among children 4 to 5 years old. Although 0.7% of children at visits in our sample before the guideline release had ADHD compared with 0.9% after, the increasing trend in diagnosis before guideline release ended in the postguideline period. These rates of preschool ADHD are lower than those found in the epidemiologic surveys of community samples that report between 2% and 4% of preschool children affected25,26 but, as expected, higher than rates found among 2- to 5-year-olds using claim data (0.5%–0.6%).19 Although a detailed chart review study of the diagnostic process used by individual clinicians was beyond the scope of this study and would be needed to definitively confirm the mechanism behind the pattern observed, our findings indicate that the standardization provided by the guideline did not trigger increases in diagnosis.

Unlike for diagnosis, rates of stimulant medication prescribing were stable across study periods. An examination of these rates is particularly important because behavior therapy, not stimulant medication treatment, is first-line management for ADHD in this age group, and previous investigations have found that nearly 80% of preschool children with ADHD received medication, compared with only slightly more than half receiving behavior therapy.19 In addition, access to behavior therapy among all children may be limited by a lack of providers offering evidence-based treatments.27 In our study, before the 2011 guideline release and driven largely by the increase in diagnosis, the likelihood of receiving medication given a diagnosis of ADHD significantly decreased but was stable after guideline release. This pattern of decreasing medication use given a diagnosis of ADHD over time may have been driven by the Preschool ADHD Treatment Study, published in 2006, which found that the effect size of stimulant treatment in preschool-aged children is lower than in school-aged children.18,28–31 Alternatively, findings may have resulted from a decrease in the severity of preschool children diagnosed with ADHD as the proportion of all preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD increased.

Practice variability is common in pediatrics14,32–34 and has triggered calls for standardization and the local implementation of clinical practice guidelines. Previously, we found widespread variation in mental health diagnosis and prescribing across pediatric primary care sites. For example, rates of ADHD diagnosis and stimulant prescribing ranged from 1% to 16% and 3% to 18%, respectively.14 Because guidelines standardize care, we expected to see decreased variation across sites after guideline release. However, we found varying responses of sites to the guideline, and the interquartile range across practices for both diagnosis and stimulant prescribing did not narrow. These findings indicate that although the overall results of our study are reassuring, practices may be responding differently to the guideline both for diagnosis and prescribing, and standardization of ADHD practice may be difficult to achieve. Additional investigation is needed to understand whether these patterns reflect local changes in the population under care, varying demand for evaluation of preschool ADHD, or known differences in how clinicians respond to guidelines.35

More broadly, this study demonstrates the utility of EHR data from across settings in monitoring changes in practice associated with the release of clinical practice guidelines. Although many barriers to guideline adherence have been described,35 the systematic measurement of practice change could provide an opportunity to assess in what circumstances and contexts guidelines demonstrate the greatest impact, where there might be unintended consequences, and when additional practice supports are needed to better achieve guideline-based care. In addition, because EHR data are available as soon as care is delivered, such assessment could be possible without the delays involved in the release of claim data. With the growing emphasis on quality improvement, practice improvement modules could then be designed to address identified barriers and improve the implementation of guideline-based care.

This study had several limitations. First, although our analyses accounted for trajectories in diagnosis and prescribing over time, this design cannot assess causality. Second, even though primary care practices typically reconcile diagnoses and medications from outside providers, medications and diagnoses from psychiatrists or other mental health providers may have been missed if primary care clinicians were unaware of them or did not document them. However, our analyses focused on preventive visits where review and updating of records were most likely to occur. Third, medication analyses were based on prescribing in the EHR. We lacked data on actual use by children. In addition, the EHRs used in the study did not have data on whether children received behavior therapy, the first-line treatment in this age group. Fourth, although our data included both Medicaid and privately insured children and children from different racial backgrounds, we lacked data on insurance type for the majority of practices. Finally, our data did not include information on whether diagnoses or prescriptions were originally made through primary care or in other settings.

Conclusions

Release of the 2011 guideline that addressed ADHD in preschoolers for the first time was associated with the end of a significantly increasing rate of diagnosis. There was no change in the overall rate of prescribing stimulants to preschool-aged children. These are reassuring results given that a standardized approach to diagnosis was recommended and stimulant treatment is not recommended as first-line therapy for this age group. More broadly, this study demonstrates the feasibility, at least in certain clinical contexts, of using EHR data from across varied pediatric practices to measure practice change associated with guideline release, a model likely to become increasingly important in driving quality improvement efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nate Blum from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for reviewing the manuscript and providing feedback. In addition, we thank the practitioners, patients, and their families from the practices in the CER2 Consortium.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CER2

Comparative Effectiveness Research Through Collaborative Clinical Reporting

- CI

confidence interval

- EHR

electronic health record

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

Footnotes

Dr Fiks contributed to conceptualization and design of the study, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafting of the initial manuscript; Drs Ross and Localio contributed to conceptualization and design of the study and analysis and interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript; Ms Mayne contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the initial manuscript; Mr Song, Ms Liu, Ms Steffes, and Ms McCarn contributed to acquisition of data and critically revised the manuscript; Drs Grundmeier and Wasserman contributed to conceptualization and design of the study and acquisition of data and critically revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Fiks was awarded an Independent Research Grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this project. The remaining authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grants R40MC24943, “Primary Care Drug Therapeutics CER in a Pediatric EHR Network”; UB5MC20286, “Pediatric Primary Care EHR Network for CER”; and UA6MC15585, “National Research Network to Improve Child Health Care.” Funding was also provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, HRSA, HHS, NICHD, or the US government. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Fiks was awarded an Independent Research Grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this project. The remaining authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2016-2928.

References

- 1.Sheldrick RC, Neger EN, Perrin EC. Concerns about development, behavior, and learning among parents seeking pediatric care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(2):156–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilliam WS. Prekindergarteners Left Behind: Expulsion Rates in State Prekindergarten Systems. New Haven, CT: Yale University Child Study Center; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garfield LD, Brown DS, Allaire BT, Ross RE, Nicol GE, Raghavan R. Psychotropic drug use among preschool children in the Medicaid program from 36 states. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):524–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser SN, Zablotsky B, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH. Diagnostic experiences of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;Sept 3(81):1–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visser SN, Bitsko RH, Danielson ML, et al. Treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children with special health care needs. J Pediatr. 2015;166(6):1423–1430.e1, 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuPaul GJ, McGoey KE, Eckert TL, VanBrakle J. Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(5):508–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Stein MA, et al. Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder for younger children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(7):695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Lee SS, Willcutt E. Instability of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(8):896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riddle MA, Yershova K, Lazzaretto D, et al. . The Preschool Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Study (PATS) 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):264–278, e262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egger HL, Kondo D, Angold A. The epidemiology and diagnostic issues in preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review. Infants Young Child. 2006;19(2):109–122 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, et al. ; Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management . ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan E, Hopkins MR, Perrin JM, Herrerias C, Homer CJ. Diagnostic practices for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a national survey of primary care physicians. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(4):201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein JN, Kelleher KJ, Baum R, et al. Variability in ADHD care in community-based pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1136–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayne SL, Ross ME, Song L, et al. Variations in mental health diagnosis and prescribing across pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20152974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McElligott JT, Lemay JR, O’Brien ES, Roland VA, Basco WT Jr, Roberts JR. Practice patterns and guideline adherence in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(10):960–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rushton JL, Fant KE, Clark SJ. Use of practice guidelines in the primary care of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1) Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/1/e23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasserman RC, Kelleher KJ, Bocian A, et al. Identification of attentional and hyperactivity problems in primary care: a report from pediatric research in office settings and the ambulatory sentinel practice network. Pediatrics. 1999;103(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/103/3/E38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1284–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Visser SN, Danielson ML, Wolraich ML, et al. Vital signs: national and state-specific patterns of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment among insured children aged 2–5 years: United States, 2008–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(17):443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson EC, Godfrey MM, Batalden PB, et al. . Clinical microsystems, part 1. The building blocks of health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(7):367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Steffes J, et al. ; Comparative Effectiveness Research Through Collaborative Electronic Reporting (CER2) Consortium . Comparative effectiveness research through a collaborative electronic reporting consortium. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/136/1/e215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Margolis B, et al. Comparative effectiveness research using the electronic medical record: an emerging area of investigation in pediatric primary care. J Pediatr. 2012;160(5):719–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiks AG, Mayne SL, Song L, et al. Changing patterns of alpha agonist medication use in children and adolescents 2009–2011. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(4):362–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergman DA. Evidence-based guidelines and critical pathways for quality improvement. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1 suppl E):225–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angold A, Erkanli A, Egger HL, Costello EJ. Stimulant treatment for children: a community perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(8):975–984, discussion 984–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, et al. Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(2):204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(3):w490–w501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kollins S, Greenhill L, Swanson J, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGough J, McCracken J, Swanson J, et al. Pharmacogenetics of methylphenidate response in preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1314–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson J, Greenhill L, Wigal T, et al. Stimulant-related reductions of growth rates in the PATS. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1304–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wigal T, Greenhill L, Chuang S, et al. Safety and tolerability of methylphenidate in preschool children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1294–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdullah K, Thorpe KE, Maguire JL, et al. Risk factors, practice variation and hematological outcomes of children identified with non-anemic iron deficiency following screening in primary care setting. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20(6):302–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garbutt JM, Yan Y, Strunk RC. Practice variation in management of childhood asthma is associated with outcome differences. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(3):474–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Russell Localio A, et al. Variation in antibiotic prescribing across a pediatric primary care network. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4(4):297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]