Significance

Many long-term cellular decisions in development, synaptic plasticity, and immunity require cells to recognize input dynamics such as pulse duration or frequency. In dynamically controlled cells, incoming stimuli are often processed and filtered by a rapid-acting signaling layer, and then passed to a downstream slow-acting layer that locks in a longer-term cellular response. Directly testing how such dual-timescale networks control dynamical regulation has been challenging because most tools in synthetic biology allow rewiring of slow gene expression circuits, but not of rapid signaling circuits. In this work, we developed modular peptide tags for engineering synthetic phosphorylation circuits. We used these phospho-regulons to build synthetic dual-timescale networks in which the dynamic responsiveness of a cell fate decision can be selectively tuned.

Keywords: dynamical control, synthetic biology, phosphorylation

Abstract

Many cells can sense and respond to time-varying stimuli, selectively triggering changes in cell fate only in response to inputs of a particular duration or frequency. A common motif in dynamically controlled cells is a dual-timescale regulatory network: although long-term fate decisions are ultimately controlled by a slow-timescale switch (e.g., gene expression), input signals are first processed by a fast-timescale signaling layer, which is hypothesized to filter what dynamic information is efficiently relayed downstream. Directly testing the design principles of how dual-timescale circuits control dynamic sensing, however, has been challenging, because most synthetic biology methods have focused solely on rewiring transcriptional circuits, which operate at a single slow timescale. Here, we report the development of a modular approach for flexibly engineering phosphorylation circuits using designed phospho-regulon motifs. By then linking rapid phospho-feedback with slower downstream transcription-based bistable switches, we can construct synthetic dual-timescale circuits in yeast in which the triggering dynamics and the end-state properties of the ON state can be selectively tuned. These phospho-regulon tools thus open up the possibility to engineer cells with customized dynamical control.

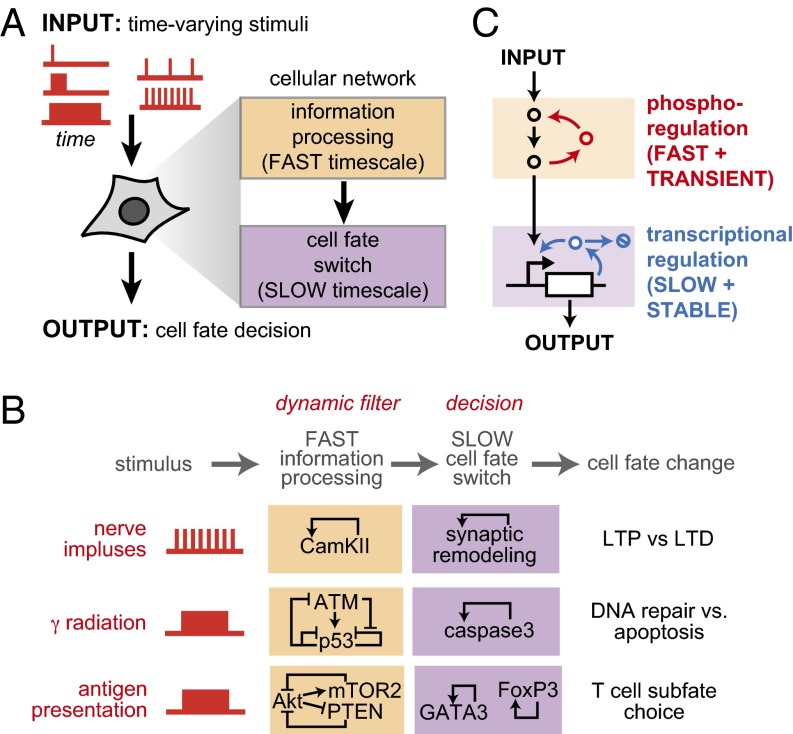

Long-term cell fates can often be selectively triggered by specific temporal patterns (dynamics) of stimulation (Fig. 1A). Relatively few cellular systems that “decode” time-varying inputs have been characterized in detail, but recurrent network motifs are beginning to emerge (1, 2). One key feature that is often observed in such systems is the interlinking of circuits that operate on distinct timescales (3–14). In perhaps the best example of a biological “dynamic gate,” the synaptic remodeling of neurons is mediated by two layers of regulation (Fig. 1B): first, an upstream circuit of rapid but transient allosteric and posttranslational changes detects incoming stimuli and filters for high-frequency pulses; second, the signal is transmitted to downstream circuits regulated by slower processes (gene expression, trafficking, and morphological changes), which ultimately can yield stable alterations in receptor localization and synaptic function (4, 6). This common motif suggests that a simple solution for achieving tunable dynamic control systems is to link fast and slow subnetworks, whereby the upstream fast system processes how the intrinsically slow downstream switch receives and responds to external dynamic inputs.

Fig. 1.

Dual-timescale architecture is a common feature of regulatory networks that dynamically control cell fate decisions. (A) Dual-timescale regulation (fast and slow layers) has been implicated as an important regulatory mechanism in cellular dynamic gates. (B) This two-layer network architecture is shared by cell fate decision circuits used in neural plasticity (3, 4), apoptosis (7, 8), and adaptive immunity (9, 10). (C) Design principles of a dual-timescale dynamic gate—rapid timescale layer processes and filters inputs, determining what temporal patterns will be propagated to the slow-timescale memory layer.

To test this hypothesis, we engineered synthetic cellular circuits based on linked fast (phosphorylation)- and slow (gene expression)-timescale modules (Fig. 1C). We first developed a versatile method for building fast-timescale signaling circuits in yeast using modular phospho-regulons. We then linked engineered phospho-feedback circuits with an intrinsically slow downstream transcription-based bistable switch, and were thereby able to generate a dynamic cell fate switch in yeast whose principal behaviors (input pulse length sensitivity and output response amplitude) could be selectively tuned by systematically altering the fast and slow regulatory layers.

To date, most engineered cellular circuits have been constructed from gene expression components, taking advantage of the modular nature of promoters (15–20). Significantly, however, the dynamic properties of transcriptional circuits are intrinsically constrained to the slow timescale of gene expression. In native regulatory networks, more rapid responses are often mediated by faster posttranscriptional modifications, such as protein phosphorylation. Our ability to create novel phosphorylation-based circuits, however, is far less developed. Successful examples of rewiring kinase pathways have largely involved redirecting kinases or phosphatases preferentially to one of several alternative preexisting substrates via engineered recruitment interactions (19, 21, 22). To construct the kind of fast-timescale feedback circuits observed in many cellular dynamic gates, we first needed to develop a more flexible platform for phospho-engineering—one that links the activity of a particular kinase to arbitrary targets in a manner that predictably alters target activity. Phospho-regulated proteins often contain bifunctional sequences [linear motif switches (23, 24)] that are efficient phosphorylation substrates for the upstream kinase as well as inducible ligands for a downstream effector domain. Here, we used one such bifunctional sequence to generate a set of synthetic modular phospho-regulation tags (phospho-regulons) controlled by Fus3, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) of the yeast mating pathway.

Results

Phosphorylation-Regulated Interaction Modules for Fast-Timescale Synthetic Circuits.

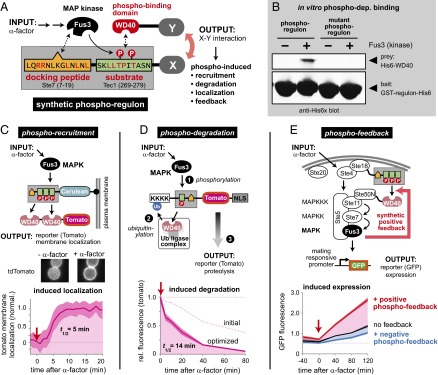

To create a robust synthetic MAPK phospho-regulon, we started with an existing substrate protein that already contains the desired core regulatory behavior (MAPK-regulated binding), and then minimized the protein to obtain a short modular sequence that can be readily fused to any target protein to achieve phospho-regulation (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1). The yeast mating pathway is one of the best-studied signal transduction networks in eukaryotes, and our work capitalized on the current molecular understanding of fast-timescale regulation by its associated MAP kinase, Fus3. The transcription factor Tec1 is a Fus3 (MAPK) substrate that, when phosphorylated, binds the WD40 domain of Cdc4 (an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex adaptor protein) (25). To generate a minimal WD40 phospho-binding motif, we combined a short, 11-residue peptide from Tec1 that, when phosphorylated, binds to the WD40 domain, with a well-characterized Fus3 docking motif (from the MAPKK Ste7) (26) to form a 49-residue phospho-regulon tag. In an in vitro binding assay, we found that this phospho-interaction module indeed only binds the Cdc4 WD40 domain when phosphorylated by the MAPK Fus3 (Fig. 2B). Consistent with this model, mutation of key phosphorylation sites in the synthetic module (Thr→Val) disrupted the Fus3-induced interaction in this and other related phospho-regulon constructs.

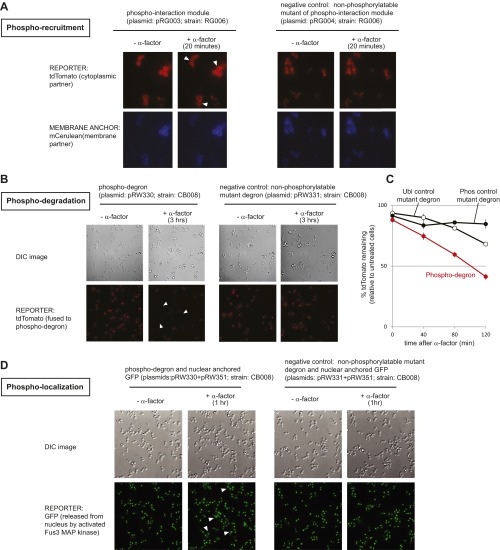

Fig. 2.

Design of phospho-regulation modules that allow engineering of synthetic kinase–substrate relationships. (A) A synthetic phospho-regulated interaction module in which phosphorylation by a yeast MAP kinase (Fus3) triggers recruitment of a phospho-binding domain (WD40 domain of Cdc4). The synthetic phospho-regulon is composed of composite linear motifs optimized for three simultaneous recognition functions: MAPK docking, MAPK phosphorylation, and phospho-binding domain recognition. Key recognition residues are denoted in red. (B) GST pull-downs confirmed phospho-dependent binding of the synthetic phospho-regulon components in vitro. (C) Phospho-regulated plasma membrane recruitment, in yeast, triggered by mating pathway activation (α-factor). “+α-factor” image taken 20 min after induction. Time course of tdTomato reporter membrane recruitment, quantified by image analysis; mean ± SD (n = 54 cells; shaded region) are shown. (D) The phospho-regulon can be converted to a phospho-dependent degradation motif (induced with α-factor) by adding lysine (K) residues to serve as ubiquitinylation sites. Phosphorylation by Fus3-triggered binding by endogenous E3 ligase Cdc4 [a substrate targeting component of the SKP1–CUL1–F-box protein (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex (25)], ubiquitination, and proteolysis. Fus3-induced degradation was enhanced by screening mutant phospho-regulons and combining enhancing mutations (Fig. S2). Time course of reporter decay in yeast after α-factor stimulation is shown (RFP fluorescence measured by flow cytometry, normalized to cell volume; see Materials and Methods). Mean ± SD (n = 3; shaded region) are shown. (E) Phospho-regulons can be used to build synthetic fast positive and negative feedback into the yeast mating pathway. Positive feedback was generated by using Fus3 phospho-regulon to induce interaction of Ste18 and Ste50N; this complex acts as a positive regulator of pathway activity, increasing the extent of Fus3 phosphorylation and downstream transcription (pFus1-GFP reporter). An analogous negative phospho-feedback loop was engineered by using the phospho-regulon to induce formation of a known inhibitory complex [Fus3 and Ste20, Fig. S5 (27)]. GFP fluorescence (measured by flow cytometry) is normalized to cell volume (Materials and Methods). Mean ± SD (n = 3; shaded region) are shown. Phospho-regulons mutated to prevent phosphorylation (pT→V) do not mediate in vivo recruitment, degradation, or feedback (Figs. S3–S5).

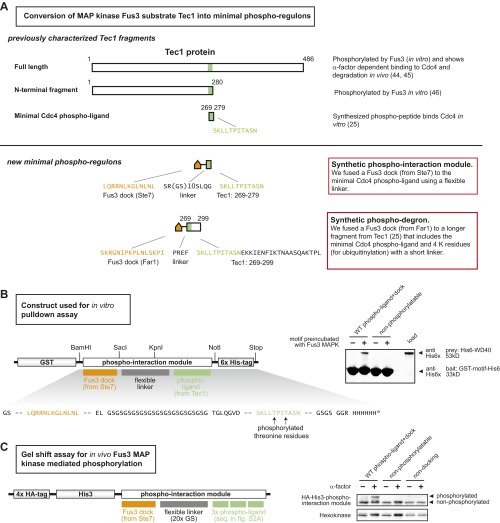

Fig. S1.

Strategy for designing Fus3 MAPK phospho-regulated protein interactions. (A) Approach to minimization of a known Fus3 phospho-regulated motif. Yeast Tec1 has been shown to be phosphorylated by Fus3 in vitro and degrades in response to α-factor in vivo (40, 41). A 280-residue N-terminal fragment of Tec1 has also been shown to be phosphorylated by Fus3 in vitro (42), but no shorter fragment has been shown to be phosphorylated by Fus3. An 11-residue fragment of Tec1 that, when synthesized as a phospho-peptide, acts as a Cdc4 phospho-ligand by itself (25) but cannot be phosphorylated by Fus3. We fused this sequence to a Fus3 dock (from Ste7) to create a minimal phospho-ligand that can be both phosphorylated by Fus3 and bound by a Cdc4 WD40 domain in vitro. We fused a longer Tec1 fragment that included 20 additional residues to a Fus3 dock (from Far1) to create a phospho-degron. (B) In vitro expression cassette for phospho-regulated interaction module. (C) A gel shift assay showed that in vivo phosphorylation of the minimal synthetic phospho-ligand required both known phospho-threonine residues (in the Tec1 fragment) and the docking motif for Fus3 MAP kinase (from Ste7). “+” samples treated with α-factor for 20 min; mutations that preclude phosphorylation (“nonphosphorylatable”) or docking (“nondocking”) described in SI Materials and Methods.

To confirm that the synthetic interaction tag mediated rapid, phospho-mediated binding in vivo, we fused three tandem copies of the synthetic phospho-regulon to a fluorescent reporter (mCerulean) tagged with a plasma membrane targeting sequence (CAAX motif), and fused two copies of the cognate Cdc4 WD40 domain to a cytoplasmic fluorescent reporter (tdTomato). Under basal conditions, the tdTomato reporter protein is distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Once cells have been stimulated with α-factor (the yeast mating pheromone that activates the Fus3 MAPK), Fus3 phosphorylates the motif, triggering rapid recruitment of the cytoplasmic reporter to the plasma membrane in ∼5 min (Fig. 2C and Figs. S2A and S3A; optimization described in SI Materials and Methods).

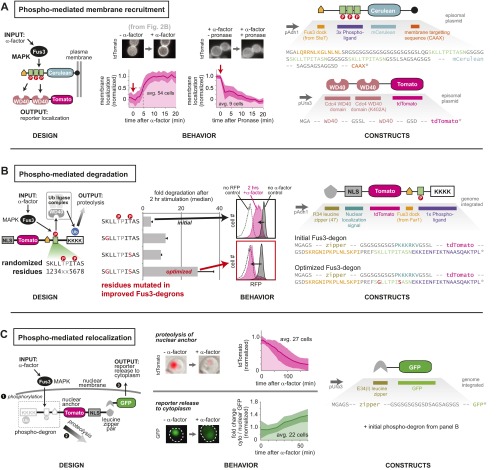

Fig. S2.

Phospho-recruitment can be used to engineer diverse response behaviors in yeast. Linear motifs and domains from yeast signaling proteins were recombined to create modular phospho-regulation tags (phospho-regulons). (A) Phospho-mediated interaction mediated by an inducible interaction between an engineered peptide and the Cdc4 WD40 domain (Fig. 2C). This synthetic interaction was reversible, and removal of α-factor (upon addition of Pronase) resulted in the rapid delocalization of tdTomato from the membrane. Functional optimization using the K402A affinity variant described in SI Materials and Methods. (B) Phospho-dependent degradation was achieved by fusing a longer sequence of Tec1 that contained four lysine residues to a Fus3 dock. This phospho-degron was then fused to tdTomato (Fig. 2D). Stimulation with the pathway inducer (α-factor) led to recognition by endogenous Cdc4 [a substrate targeting component of the SKP1–CUL1–F-box protein (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex], ubiquitination, and proteolysis. In the context of this initial Fus3-degron, mutations of the Tec1 phospho-ligand were identified that improved fold degradation, and degron performance was further enhanced by creating a synthetic phospho-regulon that combined two enhancing mutations. Median fold degradation after α-factor stimulation (relative to an unstimulated control) ± SD (n = 3) are shown for selected degrons. Normalized histograms contain >10,000 cells. (C) Phospho-dependent change in subcellular localization was achieved by fusing the phospho-degron to tdTomato, a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), and a leucine zipper constitutive protein binding domain. GFP fused to the cognate leucine zipper domain was held in the nucleus by binding to the NLS containing protein. (1) Stimulation with the pathway inducer (α-factor) led to (2) degradation of the NLS containing anchor protein, which then (3) releases GFP into the cytoplasm. Mean ± SD (shaded region) are shown. For nuclear anchor proteolysis, “+α-factor” image taken 3 h after induction; pT→V negative control, Fig. S3 B and C. For reporter release, +α-factor image taken 1 h after induction; pT→V negative control, Fig. S3D.

Fig. S3.

Sample images for engineered phospho-regulons and corresponding negative controls (nonphosphorylatable mutants) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). Microscopy images showing larger fields of cells undergoing (A) phospho-mediated interaction and (B) degradation. In these panels, phospho-regulons mutated to prevent phosphorylation (pT→V) were used as negative controls for each mode of phospho-regulation. To confirm the ubiquitination of the phospho-degron, a mutant of the original (unoptimized) phospho-degron was made (“Ubi control”) in which all four lysine residues in the extended Tec1 fragment were mutated (K→R). Constructs that block either type of posttranslational modification show impaired α-factor–induced degradation [(C) liquid culture assay; mean ± SD (n = 3) are shown]. (D) The phospho-degron was used to engineer a phospho-regulated change in GFP localization (microscopy images showing larger fields of cells).

The modular phospho-regulon approach can be readily adapted for alternative modes of posttranslational regulation: phospho-regulated degradation and changes in nuclear/cytoplasmic distribution. We assembled a modular phospho-degron (Fig. 2D and Figs. S2B and S3 B and C) using an extended region of Tec1 [characterized by Bao et al. (25)] that (i) is phosphorylated by the Fus3 MAPK, (ii) inducibly binds the endogenous yeast Cdc4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, and (iii) contains an additional poly-lysine region that facilitates ubiquitinylation. Although the fusion of this initial phospho-degron to a fluorescent reporter (tdTomato) showed slow degradation kinetics, mutational optimization of the Cdc4 binding region readily yielded an improved variant that rapidly degraded the reporter protein upon MAPK activation (t1/2 = 14 min) (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S2B). Similarly, we constructed a localization control module by fusing the phospho-degron to a nuclear anchor protein, which then released a fluorescent reporter protein into the cytoplasm upon MAPK stimulation (Figs. S2 and S3). These experiments illustrate the flexibility of phospho-regulons for circuit engineering.

To create a synthetic fast-timescale positive-feedback loop, which could alter the dynamics of a response, we used our original phospho-interaction module to drive colocalization of the mating pathway proteins Ste18 (tagged with the Fus3 phospho-regulon) with the Ste50 SAM domain (linked to the Cdc4 WD40 phospho-binding domain)—thereby reconstituting a potent synthetic activator of Fus3 MAPK [tethering of Ste18 and Ste50 SAM has been shown to mediate formation of the active MAPK signaling complex (27)] (Fig. 2E). Positive phospho-feedback reshaped the mating pathway response dynamics such that cells stimulated with pheromone displayed significantly accelerated expression of a downstream transcriptional reporter (pFus1-GFP) relative to cells containing either (i) no phospho-feedback or (ii) a circuit in which phospho-threonine residues in the recruitment module were mutated to valine. This accelerated response was correlated with rapidly amplified Fus3 phosphorylation, assayed by Western blot (Fig. S4). Notably, the synthetic phospho-regulated feedback loop did not lead to bistable memory behavior (i.e., persistent activation after stimulus removal).

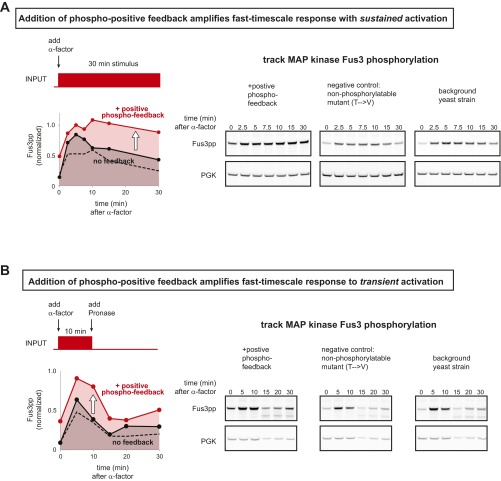

Fig. S4.

Addition of synthetic positive phospho-feedback loop enhances fast-timescale Fus3 MAP kinase response to α-factor stimulation (sustained or transient). (A) α-Factor (yeast mating pheromone) binding to receptor Ste2 triggers a canonical MAP kinase signaling cascade, leading to phosphorylation of the MAP kinase Fus3. In wild-type cells, Fus3pp activation peaks after ∼5 min, and then declines to an elevated steady-state level. (B) Addition of Pronase (a mixture of proteases that degrade α-factor) removes the stimulus and leads to rapid Fus3 dephosphorylation. When induced with a sustained α-factor stimulus, cells containing the synthetic positive phospho-feedback circuit, show higher levels of maximal Fus3pp that are sustained for at least 30 min. Once Pronase is added, the rate of Fus3 inactivation in cells with added feedback is consistent with fast-timescale phospho-regulation (<5-min t1/2; Fig. 2C). Phosphorylation sites in the negative-control phospho-regulon were mutated (pT→V) to block recruitment (shown as a black dotted line in each plot).

To engineer a fast-timescale negative-feedback loop, we used the phospho-recruitment module to colocalize components of a complex previously shown to inhibit mating pathway activation [Fus3 and the N-terminal domain of Ste20 (27)]. In this case, we observed the opposite change in pathway behavior—deceleration of pheromone induced GFP-reporter expression (Fig. S5).

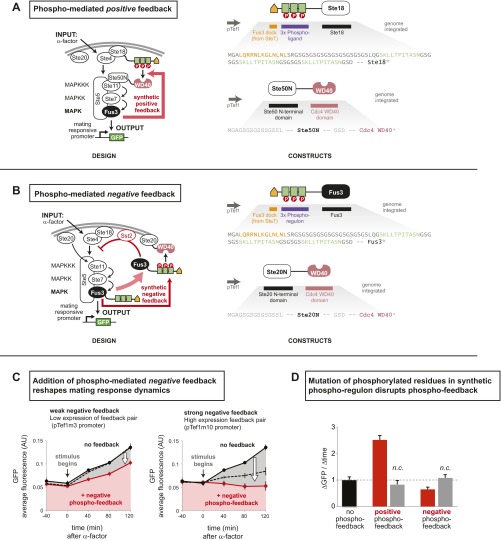

Fig. S5.

Engineered phospho-regulated feedback loops in the yeast mating pathway (Figs. 3 and 4). (A) Positive phospho-feedback was engineered by creating a Fus3-dependent interaction that promotes Ste5 recruitment to the membrane. (B) Negative phospho-feedback was engineered by linking Fus3 activity to the assembly of a complex known to inhibit the yeast mating pathway. This circuit may function by sequestering activated Fus3 at the membrane and/or by enhancing a native posttranslational negative-feedback loop mediated by Fus3 and membrane associated Sst2 (43). (C) Potency of synthetic phospho-feedback can be tuned by varying the strength of promoters driving expression of the two feedback components. Negative-feedback components coupled to a relatively weak promoter (pTef1m3) modestly reduces the rate of GFP synthesis induced by α-factor, whereas use of a stronger promoter (pTef1m10) effectively eliminates the response. The dotted line indicates the response of a phospho-regulon mutant in which the phospho-ligand has been mutated (pT→V) to preclude phosphorylation. Mean ± SD (n = 3) are shown. (D) Mutation of these phosphorylated residues (pT→V) also disrupts the synthetic positive phospho-feedback loop (shown in Fig. 2E). Mean ± SD (n = 3) are shown.

Combination of Phospho-Regulation and Transcriptional Regulation to Form Dual-Timescale Switches.

To construct a synthetic dual-timescale circuit, we then linked our engineered phospho-circuits to a slower timescale downstream switch. One of the most common and well-studied classes of synthetic switch circuits is the bistable transcriptional memory circuit—a regulatory switch that flips from one stable state to another when perturbed by a transient stimulus pulse of sufficient amplitude and duration. Bistability can be achieved using cooperative positive feedback (28), and several synthetic memory circuits have previously been constructed using autoregulated transcription factors (15–18, 29). These gene expression switches are intrinsically slow and can take hours or more of stimulation to trigger the transition from the low-expression to high-expression steady state. To understand how changes in the upstream kinase circuit could alter dynamic gating behavior, we created a simple deterministic computational model of a dual-timescale system composed of sequential phosphorylation and transcriptional feedback loops (Fig. 3A; simulation details described in SI Materials and Methods). Based on this model, a circuit with an added fast positive-feedback loop was predicted to switch ON in response to shorter stimulus pulses than a circuit with no upstream feedback. In time course simulations, the addition of positive phospho-feedback enhanced the amplitude of stimulus-dependent kinase activation, which, in turn, accelerated the rate of transcription factor synthesis, thereby decreasing the stimulus duration required to cross the bistable circuit’s threshold for self-sustaining activation. Conversely, addition of a negative phospho-feedback loop was predicted to delay the circuit’s commitment to switching ON (increase triggering time).

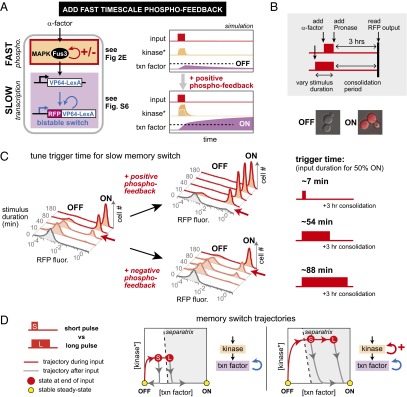

Fig. 3.

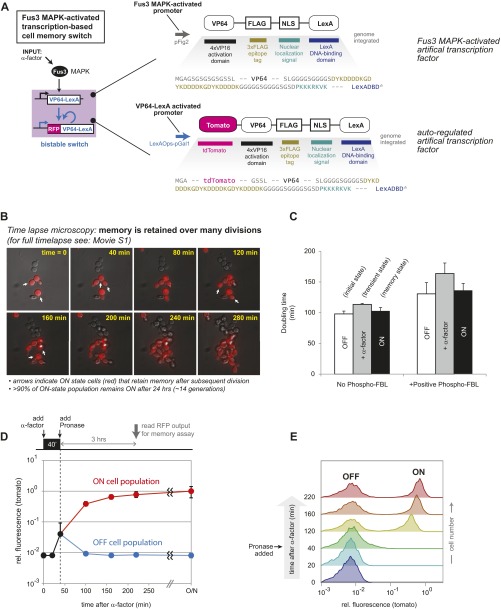

Engineering fast-timescale phospho-feedback yields yeast cell memory switch with highly tunable switching dynamics. (A) Design of a dual-timescale memory circuit: a core transcriptional bistable switch (with autoregulatory transcriptional positive feedback mediated by an synthetic fusion protein combining the VP64 activation domain and LexA DNA-binding domain) is combined with an upstream rapid-timescale MAPK signaling network that incorporates synthetic phospho-feedback loops. In deterministic computer simulations of the dual-time switch, the system flips from OFF to ON when the input duration is sufficient to build up enough transcription factor to pass the threshold for memory formation (dotted line). Addition of fast-timescale positive feedback accelerates the speed with which the system crosses this commitment threshold. (B) Pulses of varied duration can be experimentally applied to the mating pathway by adding α-factor and subsequently removing it by rapid proteolytic digestion (Pronase). After a 3-h memory consolidation phase (after end of input pulse), two cell populations emerge: memory ON cells with high levels of tdTomato (RFP), and OFF cells with basal fluorescence. ON cells stay RFP+ for >10 generations (Fig. S6). (C) Measuring trigger times for memory switch upon addition of synthetic positive or negative phospho-feedback. Normalized histograms contain >10,000 cells. Trigger times calculated as described in SI Materials and Methods, indicated by red arrows. Memory response are shown after 3-h consolidation time after transient exposure to α-factor. Addition of phospho-feedback tunes pulse trigger times by over an order of magnitude. (D) Phase plane diagrams depicting trajectories of kinase activation and transcription factor expression in response to short- and long-stimulus pulses (including how the cells relax after the end of the stimulus plus). Addition of fast phospho-feedback dramatically accelerates buildup of active kinase and leads to more rapid crossing of the commitment threshold (separatrix).

Experimentally Tuning the Trigger Time of a Dual-Timescale Bistable Switch.

We then experimentally examined the role of fast-timescale feedback in dual-timescale switches, constructing sequential fast/slow-feedback circuits (Fig. 3A) by linking synthetic phospho-feedback on the MAPK Fus3 (from Fig. 2E and Fig. S5) to a transcription-based memory circuit. The transcriptional memory switch has the following components: (i) a promoter activated by Fus3 (pFig2) drives production of an artificial transcription factor (VP64-LexA DNA binding domain), (ii) a promoter activated by the transcription factor (LexA Operator-pGal) drives production of a fluorescently tagged version of the transcription factor (tdTomato-VP64-LexA DNA binding domain) creating a self-perpetuating positive-feedback loop (Fig. S6; Movie S1 shows the memory persistence of this switch across multiple cell divisions). To measure the trigger time required for commitment to memory formation, we induced the mating pathway (by adding the peptide α-factor) for varied periods of time before quenching stimulation (by adding Pronase, a mixture of proteases that degrades α-factor) (Fig. 3B). After cells were cultured for an additional 3 h [to allow time for memory consolidation (Fig. S6)—a process that remains slow even if commitment occurs much faster], we then measured the concentration of fluorescently tagged transcription factor in single cells by FACS (≥10,000). Cells that did not pass the threshold for memory activation returned to basal tdTomato levels after 3 h (due to dilution by cell division) (Fig. 3C). In agreement with our simulations, yeast cells containing the additional negative phospho-feedback module required a longer pulse to trigger memory formation (trigger times of 88 vs. 54 min). Cells containing positive phospho-feedback module, however, were sensitized to extremely short pulses of α-factor (trigger times of 7 vs. 54 min). Thus, changes in upstream fast-timescale regulation can tune the memory switch trigger time over a 10-fold range, whereas the end states of the switch are unaltered (Fig. 3C).

Fig. S6.

Characterization of the bistable transcriptional memory module (SLOW circuit) used in this paper. (A) A bistable cellular memory switch. α-Factor induces synthesis of a trigger transcription factor that, in turn, activates an autoregulated transcription factor (fluorescently labeled with tdTomato). (B) The self-sustaining positive-feedback loop creates a memory state that persists for multiple generations. Depicted cells were isolated from a culture that had been stimulated with α-factor overnight, and then, before imaging, treated with Pronase to remove the stimulus (Movie S1). (C) Memory cells (high fluorescence, ON state) continue to divide at rates comparable to untreated cells (low fluorescence, OFF state). The threshold for triggering cellular memory is determined by the rates of protein synthesis and elimination (largely due to dilution by cell division). Our finding that the synthetic circuit has only a modest effect on yeast doubling time confirms that the reduction in stimulus duration required to trigger memory formation (approximately eightfold; Fig. 3C) is primarily due to enhancement of Fus3 activation and synthesis of the downstream transcription factor. Mean + SD (n = 3) are shown. (D) Time course plot of average cellular fluorescence before, during, and after a 40-min pulse of α-factor stimulation. Values for ON and OFF populations given when these two states are readily resolved (E). tdTomato fluorescence (measured by flow cytometry) is normalized to cell volume (Materials and Methods). Mean + SD (n = 3) are shown. (E) Representative time-resolved histograms corresponding to the same 40-min stimulus pulse shown in D. Normalized histograms contain >5,000 cells.

The functional consequences of rewiring either fast or slow layer are evident in phase-plane diagrams of transcription factor concentration and activated kinase concentration (Fig. 3D and Fig. S7). Comparison of simulated trajectories for dual-timescale circuits with and without fast positive feedback shows that addition of upstream processing impacts the time evolution of the system during the stimulus pulse—accelerating transcription factor synthesis through enhanced kinase activation—without altering the ON and OFF steady states that the system relaxes to.

Fig. S7.

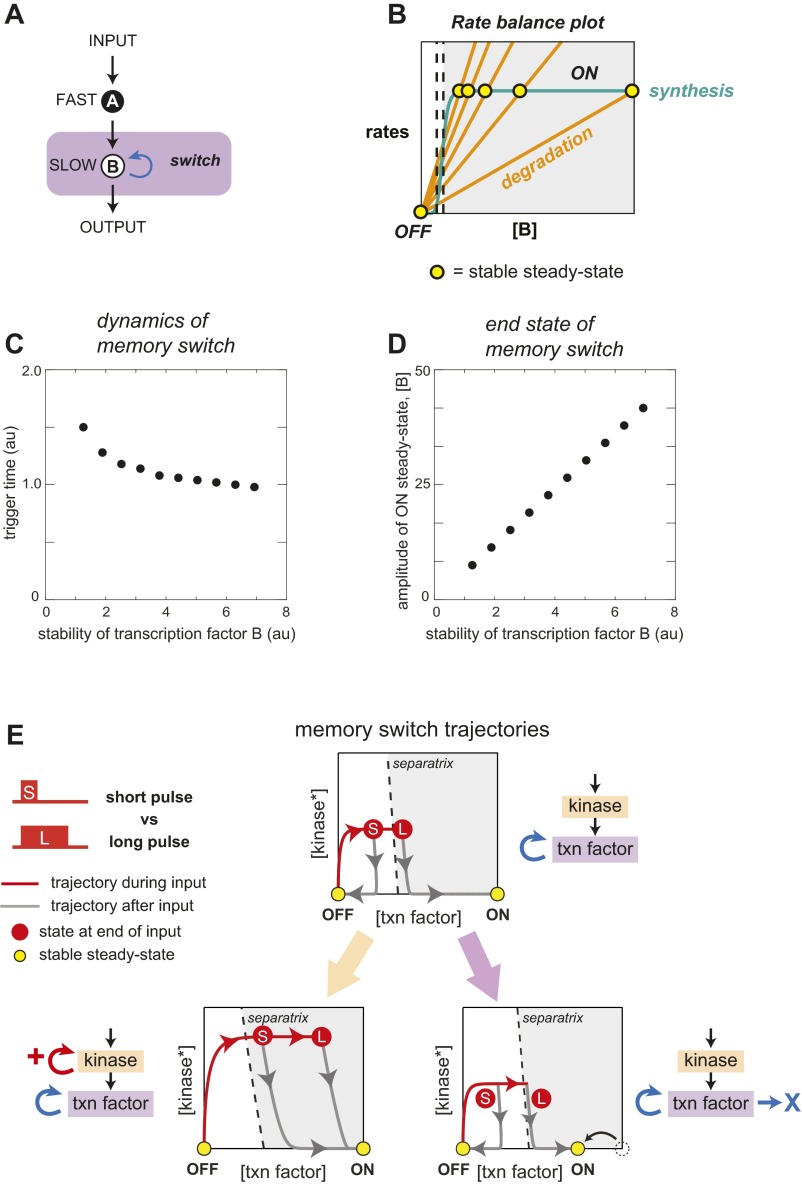

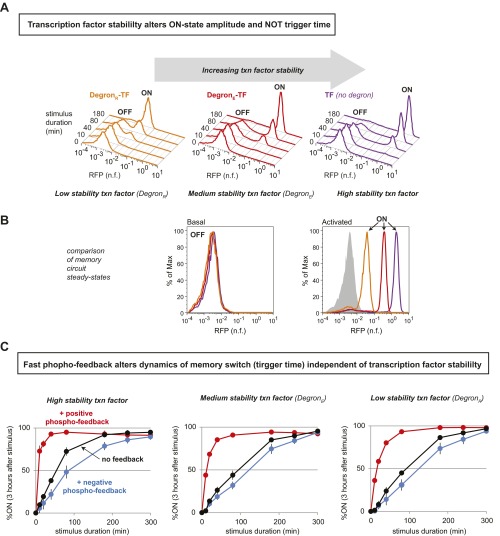

Computational analysis: transcription factor stability is predicted to primarily alter ON-state amplitude (and NOT trigger time) in dual-timescale memory circuit. (A) Diagram of a model dual-time bistable switch in which an upstream kinase activates rapidly and a downstream transcription factor is synthesized and degraded on a slower timescale. Computational model equations and parameters described in SI Materials and Methods. (B) A rate balance plot shows that changes in the rate of transcription factor degradation shift the position of the activated stable steady state (ON) but have little effect on the switch’s separatrix (threshold for turning ON; dotted lines show the range of threshold positions). (C) Deterministic simulations show that changes in transcription factor stability have little effect on the duration of stimulus required to trigger a state switch. (D) The same set of transcription factor stabilities (from C) yielded a wide range of ON state amplitudes after stimulus was removed. Notably, these results are not altered in circuits that contain an additional intermediate trigger transcription factor—more closely matching the topology of our experimental cell memory switch. (E) Phase plane diagrams depicting trajectories of kinase and transcription factor activation in response to short and long stimulus pulses. Depicts time evolution of dual-timescale circuits with or without additional fast feedback or enhanced transcription factor degradation rate.

Independent Tuning of Switch Dynamics and Steady-State Endpoints.

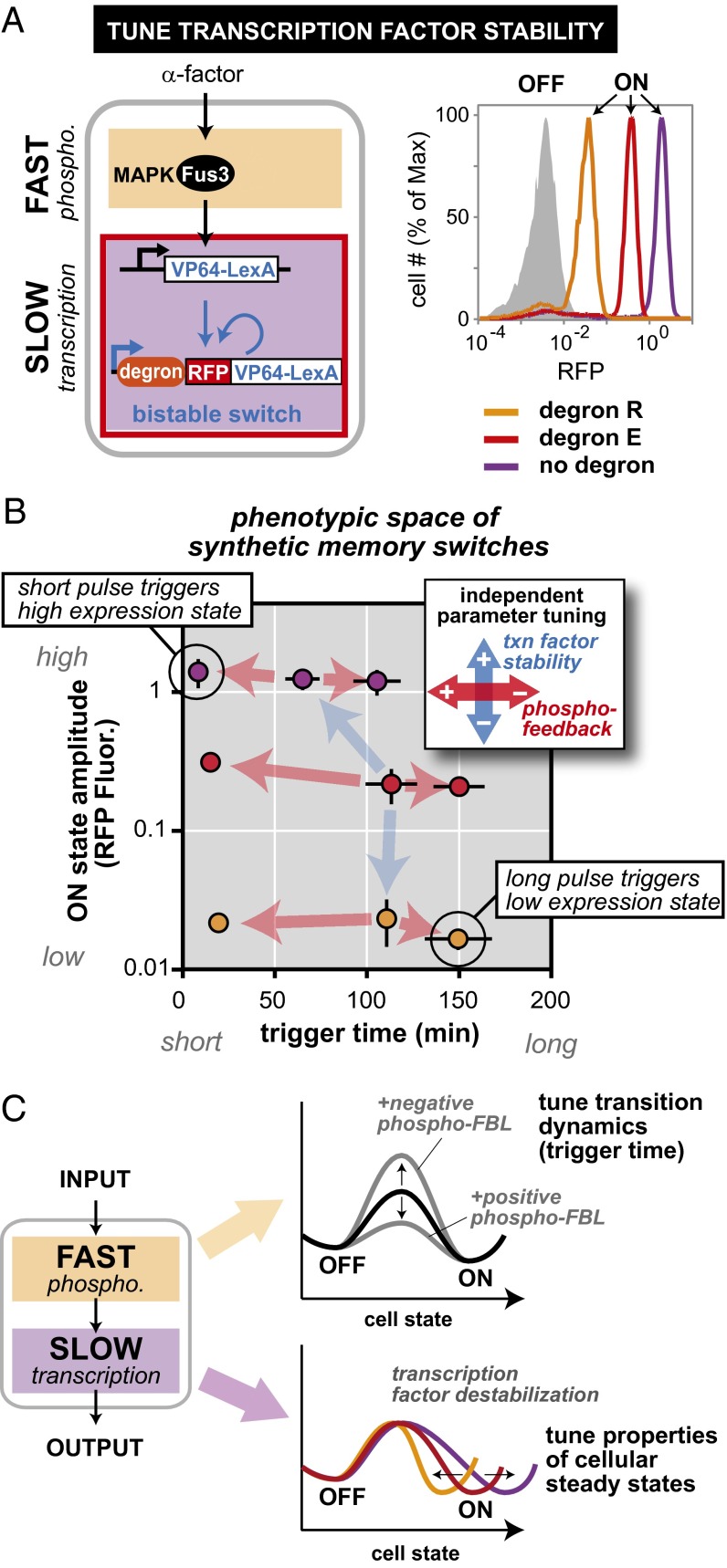

Having observed that feedback in the fast layer selectively tunes the stimulus duration required to trigger the dual-timescale switch, we wondered whether modifications in the slow layer could act as an orthogonal dial, modulating a separate property of the memory switch behavior. When we extended our computational analysis to perturbations in the slow-feedback loop components, we found that variation in the rate of transcription factor loss (degradation plus dilution) alters the position of the switch’s end state (i.e., the amplitude of the circuit’s memory response) while having relatively little effect on the trigger time (Fig. S7). We experimentally tested this prediction by destabilizing the autoregulated transcription factor in our synthetic memory circuit using N-end rule degrons. When cells containing different strength degrons [none; weak, DegronE; or strong, DegronR (30)] were stimulated with a prolonged (3-h) pulse of α-factor, a 54-fold range of ON states was observed. (Fig. 4A and Fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Independent tuning of cell fate switch dynamics and end states. (A) The ON-state steady-state amplitude of the dual-timescale circuit can be tuned by solely changing the rate of the autoregulatory transcription factor degradation [here, by adding N-end rule degron motifs: DegronE (weak) and DegronR (strong) (30)]. Normalized histograms contain >10,000 cells. (B) A small matrix of dual-time circuits illustrates how the trigger time and the steady-state amplitude of the memory ON state can be independently tuned. Changing ON state by altering stability of the transcription factor does not significantly change trigger time. Tuning trigger time by adding phospho-feedback does not significantly change ON-state amplitude. Trigger times and ON-state amplitude calculated as described in SI Materials and Methods; mean ± SD (n = 3) are shown. (C) Tuning the fast layer of a dual-timescale switch functions analogously to a catalyst by accelerating the stimulus time required to trigger cell fate change, but without changing the end OFF and ON states. Conversely, destabilizing the autoregulated transcription factor in the slow layer shifts the ON steady state but has little effect on the triggering dynamics.

Fig. S8.

Experimental analysis: independent tunability of memory switch trigger time (dynamics) and ON-state amplitude in dual-timescale memory circuit. (A) Degrons that destabilize the autoregulated transcription factor tune amplitude of the bistable system’s ON steady state but have little impact on the stimulus duration required to trigger memory. (B) Although all three transcriptional memory circuits share the same OFF (basal) state, their corresponding ON (activated) states span almost two orders of magnitude in transcription factor concentration. Histograms depict cell populations that were either untreated (basal) or induced with α-factor for a period of 5 h (activated), and then allowed to approach steady state for an additional 3 h. The gray shadow indicates the position of the OFF state (high-stability TF) for comparison. (C) Duration response plots used to calculate the trigger times (duration required to induce memory in 50% of cells) reported in Fig. 4C. Mean ± SD (n = 3) are shown.

Thus, our theoretical and experimental analysis suggested that dual-timescale switches were highly modular, such that rewiring of fast and slow regulatory layers could selectively and independently tune switch dynamic sensitivity (to pulse length) and response (amplitude of activated state). In principle, this feature would enhance the plasticity of native cellular dynamic gates and facilitate the design of diverse synthetic memory circuits. To experimentally test this possibility, we constructed a small combinatorial library of dual-timescale switches, combining fast-timescale phospho-feedback loops with downstream transcriptional feedback mediated by transcription factors with high, medium, or low stability (destabilization performed with N-end rule degrons). These synthetic circuits exhibited a broad spectrum of trigger times (7–125 min) and ON state amplitudes (84-fold range). As predicted, changes in phospho-feedback selectively modulated duration sensitivity, whereas variations transcription factor stability predominantly tuned the memory response (Fig. 4B and Fig. S8). Notably, however, we did observe a moderate increase in dynamic sensitivity when circuits contained the most stable transcription factor. In this case, it is possible that sustained positive feedback may effectively extend the duration of each input pulse.

Because changes in the strength or sign of phospho-feedback have little impact on the steady state (response amplitude) of the transcription factor-mediated memory, these fast-feedback circuits function analogously to enzymes in that they change the dynamics of switch flipping but do not alter the end states of the switch (Fig. 4C). Thus, the functional modularity of the dual-timescale regulatory switch enables cells to tailor their decision making to the environment (through changes in fast-timescale regulation) without altering, compromising, or destabilizing their long-term response (encoded by the slower downstream switch).

SI Text

SI Materials and Methods

Strain and Plasmid Construction.

Synthetic genes were introduced into yeast strains as either CENARS episomal plasmids or plasmids cut with a restriction enzyme to yield linear double-stranded DNA that singly integrates into the yeast genome using the plasmids and transformation method described by Zalatan et al. (34). All constructs were introduced into the RG006 background strain [W303 MATa, bar1::KanR, far1Δ, mfa2::pFUS1-GFP, his3, trp1, leu2, ura3, kss1Δ, fus3::fus3-as1 (Q93G)] except for those related to the in vivo gel shift and phospho-degron, both of which were conducted in a CB008 background (W303 MATa, bar1::KanR, far1Δ, his3, trp1, leu2, ura3).

Three DNA assembly methods were used. The first method results in one plasmid per ORF and is a derivative of the type IIs AarI combinatorial cloning method described by Peisajovich et al. (27). DNA parts were cloned into donor plasmids flanked by AarI restriction sites. Donor plasmids and an acceptor vector were restriction digested with AarI to yield a set of linear double-stranded DNA pieces with complementary 4-base sticky ends [“A” (GGAG), “B” (CCCT), “C” (GCGA), and “D” (TGCG)] that were then ligated to create the desired construct. In the early work, donor plasmids supplied protein domains that combined to yield the final construct’s ORF. The gene’s promoter was an existing sequence on the acceptor plasmid.

Here, we modified the above strategy to also include the promoter as a part. We introduced another 4-base sequence (GTTG) called “S” and used a modified acceptor plasmid that contains no promoter. Instead, the promoter is supplied as a linear piece of DNA, generated by restriction digestion with AarI from a donor plasmid with flanking “S” and “A” 4-base sticky ends.

The second DNA assembly method was used to create multigene episomal constructs (for Fig. 2C and Figs. S2A and S3A). This strategy used homologous recombination in yeast to join many DNA fragments in a single step (35). Building on the AarI strategy described above, two additional 4-base overhangs were selected: “X” (AATA) and “Y” (ATTT), and used to assemble individual genes in a plasmid that could only replicate in Escherichia coli. Each gene contained genetic sequences encoding a promoter and one or more protein domains flanked by 250- to 400-bp terminators and AarI restriction sites (e.g., AarI→X—5′ terminator—S—promoter—A—protein domain 1—B—protein domain 2—C—protein domain 3—D—3′ terminator—Y←AarI) such that AarI digestion could excise the entire gene as a linear fragment. Multigene constructs could then be assembled from any combination of genes whose terminators could undergo homologous recombination to build an unbroken genetic chain that included both a minimal acceptor plasmid (pRGmin; containing a CEN/ARS sequence) and LEU2 [similar to Shao et al. (35)]. Once genetic parts (promoters, domains, terminators) have been prepared, this method facilitates rapid synthesis of genetic circuits (2–3 d to transformation) with minimal labor (one-pot ligation, transformation into E. coli, DNA purification, one-pot digestion, transformation into yeast). High efficiency and low background make this method suitable for use in constructing libraries of genetic circuits in yeast.

The third DNA assembly method allowed us to create multigene constructs that could be integrated into the yeast genome (all experiments except Fig. 2C and Figs. S2A and S3A). For this purpose, we modified the TAR protocol described above in several ways. Principally, we replaced homologous recombination-based assembly with a second round of AarI multifragment cloning. For this purpose, a set of donor plasmids were generated in which two AarI sites flanked two BbsI cut sites (e.g., AarI→S—BbsI→X←BbsI—BbsI→D←BbsI—A←AarI; extra BbsI sites added to ensure efficient digestion). Donor plasmids were cleaved with BbsI and ligated with AarI cut parts (promoters, domains, terminators) to build individual genes. These genes were sequenced, digested with AarI, gel purified, and ligated into pNH605sd. Note that the internal BbsI sites are common to all genes, whereas the external AarI sites determine that gene’s position in the final assembly. Multigene assembly in pNH605sd was confirmed by AarI restriction analysis. Although slower and more labor intensive than TAR, this method of assembling gene circuits allows the precise specification of gene copy number per cell—particularly important in reducing cell-to-cell variation in protein synthesis rates. The strategy of using orthogonal type IIS restriction enzymes could be readily adapted for additional rounds of multipart ligation (to assemble >10 genes from individual regulatory parts), traditional Golden Gate cloning (no gel purification), or high-efficiency yeast transformation (to make libraries of genetic circuits). For this assembly method, unique terminator sequences were used for each gene to minimize internal homologous recombination: tAdh1 (692 bp immediately downstream of Candida albicans ADH1 stop codon), tAdh2 (400 bp immediately downstream of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADH2 stop codon), tEno2 (400 bp immediately downstream of S. cerevisiae ENO2 stop codon), and tCyc1 [250 bp immediately downstream of S. cerevisiae CYC1 stop codon, extended with flanking sequences (5′, AATAGTGCTGATTGGCTATGTAAGGTAA; 3′, CCAGAATACAGACCTGCAACGGTTG)].

Each of the phospho-circuits (recruitment, degradation, localization, and feedback) was optimized by driving expression synthetic components with constitutive promoters that spanned a wide range of strengths [pCyc1, pUra3 (215-bp sequence upstream of S. cerevisiae URA3 ATG), pAdh1 (1,500-bp sequence upstream of S. cerevisiae ADH1 ATG), and variants of pTef1 (mutants 3, 7, and 10)] (36). The phospho-recruitment circuit required additional optimization of the number and affinity of Cdc4 WD40 phospho-binding domains. In preliminary studies, we found that a single WD40 domain did not show membrane recruitment, whereas two domains in tandem lead to α-factor independent recruitment (i.e., constitutive activation in response to basal levels of Fus3 MAP kinase activity). To obtain the desired function, we introduced mutations into the Cdc4 WD40 domain that lower binding affinity for phosphorylated peptide (25). In constructs with two WD40 domains, when both domains were mutated for low affinity (K402A or R433D), we did not observe membrane recruitment. However, constructs in which one of the two domains has weak phospho-binding affinity (K402A mutant) showed α-factor–dependent recruitment (shown in Fig. 2C).

The memory module presented here was derived from prior work by Ajo-Franklin et al. (15). The initial publication describes a system in which a stimulus-responsive promoter induces expression of a “trigger” transcription factor. The trigger then induces expression of an autoregulated transcription factor (with the same DNA-binding domain; here, the LexA DBD). If enough of the downstream transcription factor is synthesized, the bistable system locks into an activated state (aka ON, memory state) and continues to produce high levels of (fluorescently labeled) transcription factor after the stimulus is removed. For the experiments described in this work, we linked synthesis of the trigger to a Fus3 MAP kinase-dependent promoter (pFig2; 750-bp sequence upstream of S. cerevisiae FIG2 ATG) and drove expression of the “memory” transcription factor with an artificial promoter (pATF; 8× LexA DNA-binding sites fused to the GAL1 promoter): GACAGGTTATCAGCAACAACACAGTCATATCCATTCTCAATTAGCTCTACCACAGTGTGTGAACCAATGTATCCAGCACCACCTGTAACCAAAACAATTTTAGAAGTACTTTCACTTTGTAACTGAGCTGTCATTTATATTGAATTTTCAAAAATTCTTACTTTTTTTTTGGATGGACGCAAAGAAGTTTAATAATCATATTACATGGCATTACCACCATATACATATCCATATACATATCCATATCTAATCTTACCTCGACTGCTGTATATAAAACCAGTGGTTATATGTCCAGTACTGCTGTATATAAAACCAGTGGTTATATGTACAGTACGTCGACTGCTGTATATAAAACCAGTGGTTATATGTACAGTACTGCTGTATATAAAACCAGTGGTTATATGTACAGTACGTCGAGGGGATGATAATGCGATTAGTTTTTTAGCCTTATTTCTGGGGTAATTAATCAGCGAAGCGATGATTTTTGATCTATTAACAGATATATAAATGCAAAAACTGCATAACCACTTTAACTAATACTTTCAACATTTTCGGTTTGTATTACTTCTTATTCAAATGTAATAAAAGTATCAACAAAAAATTGTTAATATACCTCTATACTTTAACGTCAAGGAGAAAAAACTATAATG.

Protein Expression and Purification.

An overview of proteins used as bait (bifunctional motif peptides) and prey (reader domain) in the pull-down experiment (Fig. 2B) are shown in Fig. S1. All proteins were expressed in Rosetta (DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen). Expression of bifunctional motif peptides was induced at 37 °C for 6 h for all proteins; the Cdc4 WD40 domain was expressed at 20 °C overnight. Bifunctional motif peptides were expressed with N-terminal GST and C-terminal 6×His fusion tags using Pet-13b–based expression plasmid (37). Affinity purification of bifunctional peptide motif fusions was carried out using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen), followed by affinity capture on GSH-agarose resin (Sigma). Cdc4 WD40 was purified in complex with Skp1 using the expression vector pMT 3169 (a generous gift from Frank Sicheri, University of Toronto, Toronto), according to the methods of Orlicky et al. (38). Following affinity purification, fusion tags were removed by thrombin cleavage, and the complex was dialyzed into binding buffer for pull-down experiments.

Phosphorylation of the Bifunctional Motif.

Following purification, peptide fusion proteins representing bifunctional motif candidates (Fig. S1) were eluted from GSH-agarose and dialyzed into a kinase reaction buffer for phosphorylation reactions [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 500 µM to 1 mM ATP, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol]. Phosphorylation reactions were initiated by mixing ∼10 µg of peptide fusion with Fus3 (∼100 ng) and 0.5 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and allowed to proceed at room temperature for 6 h, whereupon reactions were stopped with the addition of boiling SDS/PAGE buffer. Samples were run on SDS/PAGE gels, and the gels were dried. Incorporation of [32P]PO4 into bifunctional motif candidates was assessed by phosphorimaging using a Typhoon 8600 imager (GE Healthcare). For pull-down experiments, peptide fusions were phosphorylated while bound to GSH-agarose resin by mixing kinase reaction buffer and Fus3, incubating overnight at 4 °C, and then washing resin in binding buffer for pull-down experiments.

GST Pull-Down Binding Experiments.

Pull-down experiments were conducted by coincubating GSH-agarose resin harboring ∼250 µg of phosphorylated bifunctional motifs with 10–50 µg of the appropriate reader domain. After extensive washing with binding buffer, proteins were eluted from the resin by boiling in SDS/PAGE buffer. Samples were run on an SDS/PAGE gel, and Western blotting was used to detect binding of reader domains. For detection of WD40 binding, mouse anti–His-tag (Cell Signaling; 2366) was used. With primary antibodies, an IRDye 800CW-conjugated IgG (Li-Cor) was used, and blots were imaged on an Odyssey infrared imager (Li-Cor).

Gel Shift Assay of in Vivo, α-Factor–Dependent Phosphorylation of the Minimal Phospho-Regulon.

Constructs were generated that contained HA-tagged GST fused to a Fus3 MAP kinase docking motif (from Ste7) and three copies of the minimal Tec1 phospho-ligand (shown in Fig. S1), along with controls with mutations that disrupt either the Fus3 MAP kinase docking motif (LQAANLKGANANL) or the phospho-ligands (SKLLAPIAASN), and cloned into pRS305 [a yeast expression vector that integrates into the LEU2 locus (19)]. These three constructs were transfected into the CB008 strain and subsequently assayed by (i) diluting overnight cultures 1:100 in the morning, (ii) allowing 3 h for cells to resume growth, (iii) inducing with 1 μM α-factor for 20 min, and (iv) rapidly lysing cells for a Western blot (following the lysis protocol outlined below in Quantification of Fus3 Phosphorylation). The gel shift assay was performed using a 4–12% (wt/vol) Bis-Tris gel and an anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling; 2367S).

Microscopy and Data Analysis of Phospho-Recruitment of tdTomato to the Plasma Membrane.

Strains were grown overnight in synthetic complete medium and diluted 1:100 in the morning, and then grown 3–4 h before beginning microscopy. The 384-well glass-bottomed plates were precoated for 1 h with 1 mg/mL Con A and washed. Diluted yeast cultures were added to each well, and the plate was briefly spun to immobilize cells on the plate surface. Imaging was conducted using a Nikon Eclipse inverted microscope with an automated Prior xy stage, Perfect Focus system, and PLAN Apo 100× oil-immersion total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) objective lens. RFP and CFP epifluorescent images were collected once per minute for 23 min. After 3 min without stimulus, pheromone was added to wells to a final concentration of 1 µM.

To analyze membrane translocation of cytoplasmic WD40-tdTomato constructs, we computed the correlation between the measured intracellular distributions of (phospho-regulon)-mCerulean-CAAX and WD40-tdTomato at each time point. Cells were identified by thresholding both fluorescent channels to separate cells from background, and the correlation between each cell’s mCerulean and tdTomato pixel intensities was computed at each time point. The membrane-tethered (phospho-regulon)-mCerulean-CAAX construct was robustly present on the plasma membrane throughout each experiment, and the WD40-tdTomato redistribution to the plasma membrane. α-Factor stimulation robustly led to an increase in mCerulean-tdTomato membrane localization and a corresponding increase in correlation. As a negative control, strains expressing a nonphosphorylatable phospho-regulon variant did not show an α-factor–dependent tdTomato localization change (Fig. S3B).

Flow Cytometry.

For each α-factor stimulus experiment, triplicate yeast cell cultures (freshly transformed) were either (i) grown overnight in synthetic (−)leucine medium and diluted 1:100 the morning before the experiment, or (ii) grown overnight in synthetic (−)leucine medium with sufficient dilution to ensure cultures remained in log phase (OD600 < 1.0) and diluted to 0.05–0.1 OD600 immediately before the experiment. Dilute cultures (500 µL) were grown in 96-well blocks and induced with 1 µM α-factor (Zymo Research). To obtain time courses, 50-µL aliquots were periodically removed and immediately mixed with 10 µL of cycloheximide (30 µg/mL). The protocol for the memory assay had three steps: (i) staggered induction with α-factor (e.g., culture A induced at time 0, B at 60 min, C at 120 min…); (ii) simultaneous termination of induction with Pronase (0.2 µg/mL; Roche); (iii) removal of 50-µL aliquots (3 h after addition of Pronase) that were immediately mixed with cycloheximide. In all cases, cells arrested with cycloheximide were incubated in the dark to allow for fluorophore maturation (>2 h) and analyzed with a BD LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using a high-throughput sampler.

Analysis of flow cytometry data were performed using FlowJo (Tree Star). The fluorescence of each cell was normalized to cell volume in the manner described in Stewart-Ornstein et al. (33). Average fluorescence (a.f.) was calculated as the mean of this normalized fluorescence (n.f.). Cells with high levels of normalized fluorescence (ON peaks shown in Figs. 3C and 4A, and Fig. S8) were used to determine the degree of memory formation (%ON; fraction of highly fluorescent cells out of the total population; Fig. S8C) and the steady-state amplitude of the memory state (median normalized fluorescence of activated cells; Fig. 4B). The stimulus duration required to activate 50% of cells (trigger time; Fig. 4B) was calculated by linear interpolation. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and pathway induction and memory responses were found to be in good agreement.

Flow Cytometry Assay and Mutational Optimization of Phospho-Degron.

For each α-factor stimulus experiment (Fig. 2D and Figs. S2B and S3C), triplicate yeast cell cultures (freshly transformed) were grown overnight in synthetic (−)leucine medium and diluted 1:100 the morning before the experiment. Dilute cultures (500 µL) were grown in 96-well blocks and induced with 1 µM α-factor (Zymo Research). To obtain time courses, 50-µL aliquots were periodically removed and immediately analyzed with a BD LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using a high-throughput sampler. Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using FlowJo (Tree Star). The fluorescence of each cell was normalized to cell volume in the manner described in Stewart-Ornstein et al. (33) to calculate population mean and median. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and both the rate (t1/2) and extent (fold change) of degradation were found to be in good agreement.

To improve the original phospho-degron, eight residues immediately flanking the conserved MAP kinase substrate motif [(S/T)P] in the Tec1-derived phospho-degron were selected for randomization (shown in Fig. S2B). Eight libraries of variant degrons, each corresponding to the randomization of a single target amino acid (NNK), were constructed by overlapping PCR and cloned in place of the original degron in pRW330. Plasmid libraries were transformed separately into RG006 and selected on LEU(−) media. Individual colonies were picked and assayed in 96-well blocks in the manner described in Flow Cytometry above. In an initial screen of ∼400 cfu, colonies where ranked based on the ratio of average cellular fluorescence with vs. without α-factor treatment (1 μM for 3 h). Among the surprisingly high percentage of colonies with improved degradation performance (∼10%), those with the lowest ratio were selected for sequencing. Ultimately, two enhancing mutations that were recovered multiple times (K2G and T8S) were combined in a synthetic “optimized” degron (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2B).

Microscopy and Data Analysis of tdTomato Degradation and Change in Localization of GFP.

For phospho-degradation and phospho-localization experiments (Figs. S2 and S3), strains were grown overnight in synthetic complete medium and diluted 1:100 the morning before the experiment, and then grown for 3–4 h before beginning the experiment. A 96-well clear-bottom glass plate was treated with Con A and washed. Strains were diluted to about 0.1 OD600, sonicated briefly (Fisher Sonic Dismembrator; 11% power for 5 s using a microtip), and 100 µL was added to wells of a plate. Plates were spun down briefly to adhere yeast to the bottom. A volume of 150 µL of α-factor was added to wells, diluted so that final concentration was 3.6 µM. tdTomato, GFP, and bright-field images were collected using a Nikon TE-2000 inverted microscope with an automated Prior xy stage, Perfect Focus System, 30 °C incubator box, and a PLAN Apo 60× oil TIRF.

Degradation of tdTomato was quantified using ImageJ (W. S. Rasband; ImageJ; NIH, Bethesda; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; 1997–2011). TdTomato signal was quantified for a cell by drawing a mask around the cell and recording the integrated pixel intensity inside the mask at different time points. Background was subtracted by subtracting the product of the mask area and the image background mean pixel intensity. For quantification of the population, each trajectory for a single cell was normalized by the maximum value of the trajectory to normalize cell-to-cell variation in tdTomato expression before addition of pheromone.

The change in localization of GFP was quantified using ImageJ. For each cell, two masks were drawn. One mask was around the periphery of the cell using the bright-field channel. The second mask was around the cell nucleus, using NLS-tdTomato as a marker. A trajectory for each mask for each cell was calculated using the integrated pixel intensity inside each mask. Background was subtracted for each mask as above for tdTomato. Cytoplasmic-to-nuclear GFP was calculated using the formula: (c − n)/n, where c is the background-subtracted integrated pixel intensity for the whole cell, and n is the background-subtracted integrated pixel intensity for the nucleus. For quantification of the population, each trajectory of cytoplasmic-to-nuclear GFP ratio was normalized by the trajectory’s mean value to normalize for cell-to-cell variation in protein expression before the addition of pheromone.

For the liquid culture assay of phospho-degradation shown in Fig. S3C, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into 500 µL of synthetic medium in a 96-well block, grown for 3 h, and induced with α-factor (final concentration, 1 µM) in the culture block. Aliquots (50 µL) were periodically removed, mixed with cycloheximide (to arrest cells), and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (Flow Cytometry).

Quantification of Fus3 Phosphorylation.

To perform a fast-timescale Western blot for phosphorylated Fus3 (Fig. S4), 5-mL cell cultures [synthetic (−)leucine medium] were grown overnight. Cultures were diluted in the morning (2 mL plus 39 mL of synthetic complete medium) and incubated at 30° until the density reached 0.5 OD600. The full culture was spun down (859 × g for 2 min), media aspirated off, and cells resuspended in 800 µL (synthetic complete medium). At each time point, a 100-µL aliquot was pipetted into a 1.5-mL screw-top vial and immediately submerged in a liquid nitrogen bath. The first such aliquot was taken directly before induction with 1 µM α-factor (Zymo Research). Frozen samples were stored at −80° until rapid NaOH lysis (performed at 90 °C) (34). After lysis, samples were run on SDS/PAGE gels [4–12% (wt/vol) Bis-Tris]. Fus3pp was detected using rabbit monoclonal anti-p44/42 MAPK antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 4370). PGK was detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen; 459250). Secondary IgG antibodies were conjugated to IRDyes 800CW (Li-Cor) and 680LT (Li-Cor), respectively. Blots were imaged on an Odyssey infrared imager (Li-Cor).

Characterization of the Transcriptional Memory Module.

Time-lapse microscopy of cellular memory (Fig. S6 and Movie S1) was performed using methods similar to those described above (Microscopy and Data Analysis of tdTomato Degradation and Change in Localization of GFP). Cells that had been treated with α-factor and Pronase (Flow Cytometry) were used to inoculate an overnight culture [synthetic (−)leucine medium]. The following day, after the culture was diluted, sonicated, and spun down onto a 384-well glass-bottom plate, images of cells (tdTomato and bright-field) were collected every 20 min.

To quantify the circuit’s long-term memory behavior, cells were treated with prolonged exposure to α-factor (5 h before addition of Pronase) following the protocol outlined in Flow Cytometry. Three hours after Pronase addition, the 500-μL cell cultures were then diluted 1:1,000 in synthetic (−)leucine medium and returned for 30 °C for further incubation. The 50-μL aliquots were periodically removed, treated with cycloheximide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Twenty-four hours after α-factor had been removed, >90% of cells were still in the memory state. After 60 h of continuous culture and dilution, the memory was retained in >40% of cells (n = 12 independent cultures).

To quantify the impact of phospho-feedback, memory formation, and α-factor in cell growth rate, cells were grown overnight in a dilute culture (for continuous exponential growth), then further diluted in the morning to 0.05 OD600 in 20 mL of synthetic (−)leucine medium. One set of cultures was induced for 2 h with 1 µM α-factor (Zymo Research) before addition of Pronase. Analysis by flow cytometry confirmed that this stimulus triggered memory formation in >80% of cells. A second set of cultures was left uninduced. Culture densities (OD600) were measured every 30 min for 5 h. These data were used to calculate doubling times for cultures before, during, and after induction of cellular memory.

Quantitative Modeling.

Simulations (shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. S7) were performed with the free software package GNU Octave. The computational model equations for transcriptional feedback were as follows:

| [S1] |

| [S2] |

In Eq. S1, Aact is the concentration of active kinase (Aact = 0 at the start of each simulation), A is the concentration of inactive kinase (A = 2 at the start of each simulation; ), tunes the timescale of kinase regulation ( = 1.25), is the rate of kinase activation ( = 12.5), and is the INPUT that drives kinase activation (ON = 2; OFF = 0; variable duration). In Eq. S2, B is the concentration of the transcription factor (B = 0 at the start of each simulation), tunes the timescale of transcription factor regulation ( = 2), is the rate of transcription factor degradation/dilution ( = 0.4 in all cases except Fig. S7, where it is varied from 0.1 to 0.55), is the rate of transcription factor synthesis mediated by activated kinase ( = 6), is the rate of transcription factor autoregulated synthesis ( = 1), is the transcription factor disassociation constant ( = 1), and is the Hill coefficient for the transcriptional feedback loop ( = 8). Eqs. S1 and S2 were derived from standard equations for linear enzymatic synthesis and degradation (28), and cooperative gene expression (15).

This system was expanded to model sequential positive phospho-feedback and transcriptional feedback by modifying Eq. S1 to form the following:

| [S3] |

In Eq. S3, is the rate of kinase autoregulated synthesis ( = 4). Similarly, basic model without phospho-feedback was also expanded to model sequential negative phospho-feedback and positive transcriptional feedback by modifying Eq. S1 to form the following:

| [S4] |

In Eq. S4, tunes the strength of kinase autoinhibition ( = 4), and is the inhibition constant for the negative-feedback loop ( = 1). Eqs. S3 and S4 were derived from equations for linear enzymatic positive feedback (28), and competitive inhibition (39), respectively.

Discussion

Although it is increasingly clear that the interplay between regulatory mechanisms that operate on different timescales plays a central role in the dynamical control of cell fate decisions, the vast majority of synthetic circuits published to date are based on transcriptional regulation. Thus, our ability to understand and engineer dynamical response control is relatively primitive. The development of synthetic phospho-regulons—modular peptide tags built from linear motifs, which create customized phospho-dependent, protein–protein interactions (Fig. 2)—now makes it possible to reroute kinase signaling to directly modulate protein interaction, localization, and stability. These phospho-regulons, as demonstrated here, provide us with synthetic tools for flexibly rewiring fast-timescale cell control circuits. Using phospho-regulons, we show that a simple combination of fast and slow regulation (sequential phosphorylation-based and transcription-based feedback loops) can give rise to tunable cellular switches that are activated by custom-tuned time-varying inputs (dynamic gates). Because timescale separation permits selective control of switch sensitivity and memory response amplitude (Fig. 4), we anticipate that dual-timescale dynamic gates will be used to build switches that record the dynamics (e.g., duration or frequency) of cellular events. Dynamic gate circuits could also be used to precisely control engineered cells using information-rich modalities [such as pulse sequences (31)] or “sender” cells that encode information in time-varying outputs (32). These tools should help us to better understand the fundamental ways in which cells can encode and decode temporal information.

Materials and Methods

Strain and Plasmid Construction.

Details for all assembly protocols, plasmids, and strains (including the transcriptional memory module) are described in SI Materials and Methods and Table S1.

GST Pull-Down Binding Experiments.

Standard methods were used for expression, purification, and in vitro phosphorylation of the phospho-regulon (details in SI Materials and Methods). Pull-down experiments (Fig. 2B) were conducted by coincubating GSH-agarose resin harboring ∼250 µg of phosphorylated bifunctional motifs with 10–50 µg of the appropriate reader domain. After extensive washing with binding buffer, proteins were eluted from the resin by boiling in SDS/PAGE buffer. Samples were run on an SDS/PAGE gel, and Western blotting was used to detect binding of reader domains. For detection of WD40 binding, mouse anti–His-tag (Cell Signaling; 2366) was used. With primary antibodies, an IRDye 800CW-conjugated IgG (Li-Cor) was used, and blots were imaged on an Odyssey infrared imager (Li-Cor).

Microscopy and Data Analysis.

To assay the kinetics of phospho-recruitment of tdTomato to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2D), strains were grown overnight in synthetic complete medium and diluted 1:100 in the morning, and then grown 3–4 h before beginning microscopy in Con A-coated 384-well plates. RFP and CFP epifluorescent images were collected once per minute for 23 min, with α-factor (1 µM final concentration) added after the third minute. Cells were identified by thresholding both fluorescent channels, and membrane translocation of cytoplasmic WD40-tdTomato was computed at each time point as the correlation between the measured intracellular distributions of (phospho-regulon)-mCerulean-CAAX and WD40-tdTomato. Additional details for the microscopy setup and analysis described in SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry.

Full protocols for the flow cytometry assays and analysis are described in SI Materials and Methods. Briefly, for α-factor experiments, triplicate 500-μL yeast cultures in log phase were induced for variable periods of time [1 μM α-factor (Zymo Research), removed by adding 0.2 μg/mL Pronase (Roche)], with aliquots arrested with cycloheximide (allowing time for fluorophore maturation) before analysis with a BD LSR-II flow cytometer. Analysis of flow cytometry data were performed using FlowJo (Tree Star). The fluorescence of each cell was normalized to cell volume (n.f.) in the manner described by Stewart-Ornstein et al. (33).

Quantitative Modeling.

Simulations were performed with the free software package GNU Octave. Computational model equations are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the Octave development community. This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (to R.M.G.), a University of California, San Francisco/Genentech Graduate Fellowship (to R.E.W.), a Cancer Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship (to J.E.T.), a Jane Coffin Childs Fund Postdoctoral Fellowship (to S.Y.), the National Science Foundation Synthetic Biology and Engineering Research Center (R.M.G. and W.A.L.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.M.G. and W.A.L.), and National Institutes of Health Grants GM55040, GM62583, EY016546, and GM081879.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: W.A.L. is a founder of Cell Design Labs and a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1610973113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Purvis JE, Lahav G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell. 2013;152(5):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yosef N, Regev A. Impulse control: Temporal dynamics in gene transcription. Cell. 2011;144(6):886–896. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucchesi W, Mizuno K, Giese KP. Novel insights into CaMKII function and regulation during memory formation. Brain Res Bull. 2011;85(1-2):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandel ER, Dudai Y, Mayford MR. The molecular and systems biology of memory. Cell. 2014;157(1):163–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen R-H, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(8):556–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West AE, Greenberg ME. Neuronal activity-regulated gene transcription in synapse development and cognitive function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(6):a005744. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batchelor E, Loewer A, Mock C, Lahav G. Stimulus-dependent dynamics of p53 in single cells. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:488. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X-P, Liu F, Cheng Z, Wang W. Cell fate decision mediated by p53 pulses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(30):12245–12250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813088106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawse WF, et al. Cutting Edge: Differential regulation of PTEN by TCR, Akt, and FoxO1 controls CD4+ T cell fate decisions. J Immunol. 2015;194(10):4615–4619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miskov-Zivanov N, Turner MS, Kane LP, Morel PA, Faeder JR. The duration of T cell stimulation is a critical determinant of cell fate and plasticity. Sci Signal. 2013;6(300):ra97. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribes V, Briscoe J. Establishing and interpreting graded Sonic Hedgehog signaling during vertebrate neural tube patterning: The role of negative feedback. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(2):a002014. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balaskas N, et al. Gene regulatory logic for reading the Sonic Hedgehog signaling gradient in the vertebrate neural tube. Cell. 2012;148(1-2):273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen M, et al. Ptch1 and Gli regulate Shh signalling dynamics via multiple mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6709. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajo-Franklin CM, et al. Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21(18):2271–2276. doi: 10.1101/gad.1586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;403(6767):339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingolia NT, Murray AW. Positive-feedback loops as a flexible biological module. Curr Biol. 2007;17(8):668–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi H, et al. Programmable cells: Interfacing natural and engineered gene networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(22):8414–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402940101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bashor CJ, Helman NC, Yan S, Lim WA. Using engineered scaffold interactions to reshape MAP kinase pathway signaling dynamics. Science. 2008;319(5869):1539–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1151153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Way JC, Collins JJ, Keasling JD, Silver PA. Integrating biological redesign: Where synthetic biology came from and where it needs to go. Cell. 2014;157(1):151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S-H, Zarrinpar A, Lim WA. Rewiring MAP kinase pathways using alternative scaffold assembly mechanisms. Science. 2003;299(5609):1061–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.1076979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Won AP, Garbarino JE, Lim WA. Recruitment interactions can override catalytic interactions in determining the functional identity of a protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(24):9809–9814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016337108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tompa P, Davey NE, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. A million peptide motifs for the molecular biologist. Mol Cell. 2014;55(2):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller ML, et al. Linear motif atlas for phosphorylation-dependent signaling. Sci Signal. 2008;1(35):ra2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1159433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao MZ, Shock TR, Madhani HD. Multisite phosphorylation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae filamentous growth regulator Tec1 is required for its recognition by the E3 ubiquitin ligase adaptor Cdc4 and its subsequent destruction in vivo. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9(1):31–36. doi: 10.1128/EC.00250-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reményi A, Good MC, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. The role of docking interactions in mediating signaling input, output, and discrimination in the yeast MAPK network. Mol Cell. 2005;20(6):951–962. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peisajovich SG, Garbarino JE, Wei P, Lim WA. Rapid diversification of cell signaling phenotypes by modular domain recombination. Science. 2010;328(5976):368–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1182376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrell JE, Xiong W. Bistability in cell signaling: How to make continuous processes discontinuous, and reversible processes irreversible. Chaos. 2001;11(1):227–236. doi: 10.1063/1.1349894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inniss MC, Silver PA. Building synthetic memory. Curr Biol. 2013;23(17):R812–R816. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hackett EA, Esch RK, Maleri S, Errede B. A family of destabilized cyan fluorescent proteins as transcriptional reporters in S. cerevisiae. Yeast. 2006;23(5):333–349. doi: 10.1002/yea.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milias-Argeitis A, et al. In silico feedback for in vivo regulation of a gene expression circuit. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(12):1114–1116. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prindle A, et al. Rapid and tunable post-translational coupling of genetic circuits. Nature. 2014;508(7496):387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart-Ornstein J, Weissman JS, El-Samad H. Cellular noise regulons underlie fluctuations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2012;45(4):483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zalatan JG, Coyle SM, Rajan S, Sidhu SS, Lim WA. Conformational control of the Ste5 scaffold protein insulates against MAP kinase misactivation. Science. 2012;337(6099):1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1220683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao Z, Zhao H, Zhao H. DNA assembler, an in vivo genetic method for rapid construction of biochemical pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(2):e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevoigt E, et al. Engineering of promoter replacement cassettes for fine-tuning of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(8):5266–5273. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00530-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reményi A, Good MC, Lim WA. Docking interactions in protein kinase and phosphatase networks. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(6):676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orlicky S, Tang X, Willems A, Tyers M, Sicheri F. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112(2):243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voet D, Voet JG, Pratt CW. Fundamentals of Biochemistry. Wiley; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou S, Huang L, Liu H. Fus3-regulated Tec1 degradation through SCFCdc4 determines MAPK signaling specificity during mating in yeast. Cell. 2004;119(7):981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao MZ, Schwartz MA, Cantin GT, Yates JR, 3rd, Madhani HD. Pheromone-dependent destruction of the Tec1 transcription factor is required for MAP kinase signaling specificity in yeast. Cell. 2004;119(7):991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brückner S, et al. Differential regulation of Tec1 by Fus3 and Kss1 confers signaling specificity in yeast development. Curr Genet. 2004;46(6):331–342. doi: 10.1007/s00294-004-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrison TR, et al. Feedback phosphorylation of an RGS protein by MAP kinase in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36387–36391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.